Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ancient Newari WaterSupply Systems in Nepals Kathmandu Valley

Caricato da

krishnaamatya_47Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ancient Newari WaterSupply Systems in Nepals Kathmandu Valley

Caricato da

krishnaamatya_47Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Ancient Newari Water-Supply Systems in Nepal's Kathmandu Valley Author(s): Jonathan C. Spodek Source: APT Bulletin, Vol.

33, No. 2/3 (2002), pp. 65-69 Published by: Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1504758 . Accessed: 08/08/2013 04:41

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to APT Bulletin.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ancient

Nepal's

Newari Systems Water-Supply Kathmandu Valley

in

JONATHAN C. SPODEK

The traditional water sources in and around the city of Patan are examined in their physical and cultural contexts.

To

Bodhnath Kmand t Swayambunath/ Changu Ngrako

Airport

A Bode

Narayan

Near the base of Mount Everestin the Indiansubcontinent,Nepal's KathmanduValleyis a place of immense Valculturalrichness.The Kathmandu ley, with its seven WorldHeritage Zones, evokes wonder in the visitorwith its sheernumberof religiousstructures and monuments.Beyondthese monuments and their immediateenvirons, however,thereare other,less wellknown sites and resourcesimportantto the physicaland social well-beingof the indigenouspeople, the Newari. The settlementsin the valley,most notably the city of Patan,are characterized by a fabric relieved urban only by pubtight lic squares,which often includewells, waterspouts,drinkingfountains,or other accessto potable water.The wateringplaces in and aroundPatanare of particularinterestbecausethey reflect the architectural, artistic,social, and engineeringheritageof this ancient the international people. Unfortunately, to the pressure preserve monumentsof the Kathmandu Valley'sWorldHeritage Zones has overshadowedand in some ways adverselyaffectedthese sites of criticallocal importance. This paperexaminesthe traditional water sourcesof the Newari people in and aroundthe city of Patanby situating these sites in theirphysicaland culturalcontexts. Moreover,it highlights the ongoing challengespreservationists face in maintainingkey componentsof daily life in Newari communalsociety. The KathmanduValley

To

Lubhu Kodari The Kathmandu Valleyis a geographic Okm 5kmbasin,coveringroughly 180 square

Godavari

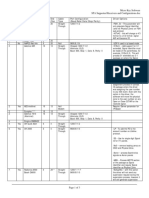

Fig.1. Mapof Kathmandu Valley.Drawing by the author.

lands in the miles, of fertileagricultural middlerangesof the Himalayas.The name Nepal originallyappliedonly to this valley,the culturalcore of the counand trade settletry.Earlyagricultural

ments in the valley prosperedlargelydue to theircentrallocation along the ancient traderoutes betweenIndiaand Tibet.The use of these traderoutes has kept this landlockedvalley from cultural isolation. The valley is strewnwith small traditional villages,shrines,and temples, with the royal cities of Kathmandu, Patan,and Baktapurdominatingthe area (Fig. 1). Duringthe golden age of the valley in the Malla period from the thirteenthto the eighteenthcenturies, the threecities competedto outdo each and urbandevelother in architectural These small opment. kingdoms,or cityunder states,existed independently relatedMalla rulersuntil 1768, when they were unifiedinto a single state underthe Shah dynasty.It was during the Malla periodthat the sites where the Newari obtainedtheirwater in the undervalley,and in Patanin particular, went the most elaboratedevelopment. The Newari, a people of mixed ethnic and culturalorigin,are regardedas the originalinhabitantsof the KathmanduValley.They dominatedthe life and cultureof the threekingdomsand suppliedthe independentrulerspriorto unificationunderthe Shahin the eighteenthcentury.Althoughtoday many ethnicgroupsmake up modernNepal, the Newari continueto maintaintheir culturalheritageby preserving their languageand customs.The artisticskill of the Newari is displayedin their stone sculptures,shrines,and temples,as well as in the architectural structures they built to mark theirpublic water sources. These structuresincorporatestone carving,woodcarving,metalwork,and work and date beforethe terra-cotta Shahdynasty. The historyof the Kathmandu Valley can be dividedinto threeperiodsor dynasties:the Licchaviperiod (A.D.

65

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66

APT BULLETIN

Fig. 2. Pati (publicshelter) near the stepwell in Lubhu. All photographs by the author.

300-900), the Transitional period (A.D. 900-1200), and the Malla period (A.D. 1200-1768). The last period is wellin the valley today through represented its urbandevelopmentand architecture. While ancientstructures associatedwith the water supply are not restrictedto the in the urban areas,they are concentrated three principalcities of Kathmandu, Patan, and Baktapur. Patan The KathmanduValleywas placed on UNESCO'sWorldHeritageList in

1979.1 The historic Dubar (palace)

period. The magnificenttemples, shrines,and stupas in Patanare interwoven throughoutthe tight urbanfabric. The structures constructedduringthe Malla period, both religiousand domestic, are adornedwith exquisitelycrafted and carvedornament. Daily life in Patanhas always revolved aroundits public water supply. Houses are built arounda chowk, or courtyard,which providesthe social centerfor the neighborhood.Eachtole ward, or street)has a public (quarter, square.These squaresare not formal plazas, but simplyopen areasthat relieve the closely built environment.The

public squaresgenerallyconsist of a temple or shrine,a shelterfor travelers makinga pilgrimage,and public access to water.The sheltermight be a dharma'-la (Sanskrit for "charitable which is an enclosedrest asylum"2), house, or it might be a pati, a simple raisedplatformcover with a roof structure (Fig.2). These sheltersfunction as places for people to rest and socialize,as well as for travelersto stay overnight. Patan'sDurbarSquareboasts threeof the most elaboratelybuilt watering places:the TushaHiti, the LvaHiti, and the MangahHiti. The latterfeaturesa public sunkenstepwellwith carved stone waterspouts(Fig.3). The Tusha Hiti and the Lva Hiti are found within two of the threepalace chowks. For centuries,people havegatheredat the nearestchowk to drawwater for drinking,cooking, washing,and ritual bathing.In additionto their utilitarian functionof providingwater,these sites are an integralpart of the culture,playing a centralrole in the social, spiritual and communallife of the Newari people. Components of PublicWater Sources Potablewater in the cities and villagesof Kathmandu Valleywas historicallyand is still today in many placesobtainedfrom a seriesof man-made ponds and runningfountainsin stepwells. These are part of a sophisticated networkfound throughout water-supply the valley.

Squareof Patan,includingits immediate urbansetting,is one of seven Monumental Zones of this WorldHeritageSite. Historically,Patanwas the seat of the valley'slargestkingdom.Today,it ranks second in size among the threemajor cities. Locatedsouth of Kathmandu across the BagmatiRiver,Patanis virtually contiguouswith its neighboringcity as a resultof moderndevelopment. or "the Sometimescalled Chakrakara, city in a circularform," Patanwas originallylaid out in the thirdcentury B.C. in the form of a circlewith a Buddhist stupa, a moundedstructurecontainingreligiousrelics,at each of its cardinalpoints. Anothername for the or "cityof beauty," city is Lalitpur, to the elaboratearchitecture referring and public spaces built duringthe Malla

Fig. 3. Mangah Hiti(stepwell), DurbarSquare, Patan.

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANCIENT NEWARI WATER-SUPPLY

SYSTEMS

67

inthe Mangah Hiti, Fig.4. Stonewaterspout

Patan.

sculptures,stone taps, and friezessurvivefrom the Transitional period, but these earlierelementshave often been incorporatedinto structures dating primarilyfrom the Malla period.Many carvedstone taps can even be dated stylisticallyto the earliestLicchaviperiod. Interestingly, a numberof these survivenot only as taps in the later or stepwells,but also in other structures in paved roads. While inscriptions and/or stylisticappearanceallows certain decorativeelementsof the stepwells to be dated to the Licchavior Transitional periods,the stepwellsthemselves rarelydate from more than five hundred years ago.s Drinkingfountains. Drinkingfountains in Nepali;jahdi~in Newari) (tutedhara are manuallyfilledstone containersor troughs,with spigots for drinking.These are often located at templesand in courtyardsnear a well or stepwell. These spigot fountainsare rarelyin use today. Water holes. Waterholes (kuvain excavated Newari) are simple,circular, shallow wells at naturalsprings.Deeper wells (inarain Nepali; ti~inNewari) excavatedto the level of the ground water providean additionalsourceof water for the city but do not play a role in the social and culturallife as do the stepwellsand ponds.

The ponds and stepwellsprovide good examplesof Newari craftsmanship and design.Wallsand floors are laid with elaboratecarvingsand brickwork. The waterspoutsof the stepwellsare finelycarvedin stone, usually in the forms of mythicalcreatures. and artisBeyondtheir architectural tic significance, these placeshave spirias water is considered tual significance, sacred.The stepwellsand ponds are venuesfor ritualbathing.Smallshrines or carvingsin the stepwellsoften repeat the imageryfound in the largerreligious shrinesconstructedin the vicinityof the fountains (Fig. 5). Water-SupplySystem The traditionalNewari water-supply componentsare not only fascinating visible featuresof the urbanand cultural landscape;they are also examplesof earlypublic engineeringsystems.Hydrologistshave determinedthe sources of many stepwellsto be underground aquifersand springsfound throughout the Kathmandu Valley.In additionto these naturalsources,some of the manmade ponds are believedto play an importantrole in chargingparts of the water system.Thereare underground instanceswhere naturalwater sources do not provideconsistentwater supply or adequatewaterpressureto maintain a specificseriesof publicwatering places;in these cases, the ponds fulfill those needs.6

Man-made ponds. Man-madeponds (calledpokari in Nepali; phuku in Newari)3are urbanreservoirs.Located throughoutthe cities or on their outskirts,these brick-linedreservoirs have steps aroundtheir perimeters to providesafe access to the water.They vary in size from largelakes associated with palacecompoundsto bathtub-size ponds. It has been difficultto date any of the ponds to beforethe Malla period. found on the stone Inscriptions Rani Pokari or Queen surrounding Lake,in the northeastsection of date this pond to the Kathmandu, seventeenthcentury,duringthe Malla period.4 Stepwells. Stepwells(dungecdirai, Nepali for stone tap; hiti, Newari for stepwell,or gahiti, for deep stepwell)are continuouslyrunningwater taps with the spouts carvedin animalform. The spouts are carvedfrom local grayishgreen basalt (Fig.4). The taps are located at the bottom of stepped,or terraced,pits. The waterspoutsare interconnected by clay piping, and operatethroughgravity.The size and depth of the stepwellsvary greatly dependingon the location within the city and position in the chain of wells. Some stepwellshave only one waterspout,while others have many more. The stepwells,with their imaginativewaterspouts,are the most distinctiveof these architecturally ancientwateringplaces. Numerous decorativefeaturesof the stepwells- such as individualstone

Fig. 5. Hiti(stepwell) in Baktapurwith shrine above stone tap.

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68

APT BULLETIN

A sophisticatedgravity-propelled distributionsystemof clay and terracotta piping links these aquifersto a seriesof ponds and/orstepwells.Water flows from the source to the firststepwell in the chain via underground clay pipes. The water dischargesat the stepwell througha carvedstone waterspout and is collectedin a drain below. The underground drainpipeof the firststepwell supplieswater to the subsequent stepwell in the system.This arrangement explains why the stepwellsare placed deeperand deeperbelow groundlevel in the supply chain. The componentsof the underground distributionsystemare just as remarkable as the stepwells'visible features. Many of the originalsupply and drain lines still functiontoday.While many of these lines are presumedto have been rebuiltor improvedduringthe Malla period, there are cases of pipelineswith inscriptionsfrom earlierperiods.Inscriptionsdating from A.D. 590 are on the water supplylines for the Mangah Hiti, one of the three stepwellsin Locals still Patan'sDurbarSquare.7 draw water daily from the Mangah Hiti. Preservation Context The upkeepof Patan'sponds and stepthe wells is sporadicat best. Historically, responsibilityfor maintenanceresided with local Newari families,organized into guthi, or groups with specificsocial and religiousobligations. Gfithiwere assignedto specificshrines,public structures, stepwells,or ponds. The practice of forminggithi, along with the traditional caste system,is breakingdown in modernNepal, with the push toward normalizationof ethnic groups.The decline of this social system,including the loss of associatedfinancialsupport, of the has resultedin the deterioration stepwells and ponds. Added to the difficultyof maintainingthese ponds and stepwellsis their ambiguouslegal status. In many cases, it cannot be determined whetherthey are publiclyor privatelyowned.8This complicatesthe problemof upkeepand has led to the neglect or abandonmentof certainsites (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Abandoned hiti (stepwell) in Lubhu.

New developmentposes a real threat to the ponds and stepwellsof Patan. Developmentthroughoutthe KathmanduValleyis occurringwith little oversight.A 1999 reportby the World that HeritageCommitteerecommended on the Kathmandu be Valley placed its List of WorldHeritagein Danger.A furtherrecommendation was to remove certainareasin the valley from World HeritageMonumentalZones, basedon the seriousdegreeof uncontrolleddevelof the opment and the deterioration of Monumental Zones. The the integrity committeespecificallynoted the Nepalese government's inabilityto control development,retainhistoric buildingsin situ, and addressillegal constructionand alterationof historic structures. The reportstatedthat "the demolitionand new constructionor alterationsof historicbuildingswithin the Kathmandu Valleyhave persistedin and spite of the concertedinternational nationalefforts,resultingin the loss or of continuousand gradualdeterioration feaornamental materials,structure, tures, and architectural coherence...."9 This assessmentappliesto the ancient wateringplaces of Patan.There,and throughoutthe valley,efforts have been made to developmunicipalwater systems. By obviatingthe need for stepwells and ponds, municipalwater systems would come at great social and cultural expense.

The city of Patan,workingwith the Departmentof Nepali government's Archeology,took the firststep toward an invenpreservation by undertaking tory of its stepwellsin 1995. This inventory was limitedto the stepwellsthemselves and did not investigatethe sources of the water or the distributionsystem. aquifers, Locatingthe underground springs,and piping would be a more protractedprocess,involvingexpensive and time-consuming tracunderground efforts. On several distrioccasions, ing bution piping has been brokenor disruptedduringexcavationfor new constructionor infrastructure improveof the ment, resultingin the interruption water supplyto one or more stepwells. Repairor reroutingof piping is difficult urban due to the dense and irregular structureand to poor governmentoversight of public works. UNESCOrecognizesthe traditional water supply systemas a uniquefeature of the culturalheritageof the KathmanduValley.In particular, the organization has focused on the stepwellsof UNESCOKaththe city of Kathmandu. manduis currentlyassistingthe KathmanduMetropolitanCity Officein the restorationof its stepwells.The first was completedin projectin Kathmandu Three 1999 throughthis partnership. more stepwellsare currentlybeing rehawith additional bilitatedin Kathmandu, financialsupportfrom the Japanese Another21 stepwellshave Embassy. been identifiedfor restorationby UNTo date, neither ESCOKathmandu.l? UNESCOnor any municipalagencies have made an outside of Kathmandu effort to extend the restorationprogram to Patanor other settlements. Summary While individualstepwellsin Patan stand out as superbexamplesof architecturalstructures, it is the entiresystem of ponds, stepwells,and fountainsthat meritscloser surveyand documentation. The evolution and continuoususe of these water-supply systemsduringthe last fifteenhundredyearshas made them an integralpart of the architectural, artistic,and social fabricof Patanand Newari society.As importantgathering and spaces for daily ritual,refreshment,

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANCIENT NEWARI WATER-SUPPLY

SYSTEMS

69

rest, the stepwellsin particularhave comdevelopedinto rich architectural plexes. It is no wonder they have historically attractedprivateand royal donations for their preservation. These sites are also importantremindersof the Newari'searlyengineeringachievement in providingpotable water to the inhabitants of Patanand its environs,thus developinga viable and enduringpart of the city'sinfrastructure. Lackof funding,uncertaintyof docuownership,poor infrastructure and lack of control over new mentation, with to these waterdevelopment regard ing places are graveconcernsof Patan's and architectural compreservationist munity.With the attentiondrawnto the Kathmandu Valleyfrom the World Committee and the interest Heritage from UNESCOin Kathmandu's water supplysystem,it is hoped that funding can be securedfor additionalinventory work on the distributionsystemand the less visiblecomponentsof Patan'spublic water network.

JONATHAN C. SPODEK is an architect and assistant professor of architectureat Ball State University.In Patan, Nepal, during the summer of 1999, he developed and presented a short course on historic preservationfor architects, engineers, UNESCO staff, government officials, and students. He continues to consult with architecture/planningstudents and preservation professionals in the KathmanduValley region.

3. Nepali, closely related to Hindi, is the official national language of Nepal, as established under the Shah dynasty. There are many other languages spoken in modern Nepal. Newari, the principal language of the KathmanduValley prior to the Shah dynasty, is still spoken by the Newari ethnic group. 4. T. W. Clark, "The Rani Pokhri Inscription, Kathmandu," Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 20 (1975): 173. 5. See Shobha Shrestha, "Inventory:City of Patan. Chapter 2, Hiti (Stepwells)," draft report for His Majesty's Government of Nepal, Ministry of Education, Culture, and Social Welfare, Department of Archeology, 1995, 1. 6. Interview with Hari K. Shrestha,Assistant Professor of Engineering,Nepal Engineering College, Bhaktapur,Nepal, June 1999. 7. Shobha Shrestha, 97. 8. The 1995 inventory conducted by Shobha Shresthadetermined ownership for approximately half of Patan's stepwells. 9. "Report of the Twenty-ThirdExtraordinary Session of the Bureau (WHC-99 / Conf. 209/6) Relating to the State Of Conservation of Properties Inscribed on The World Heritage List," Nov. 29-Dec. 4, 1999. 10. "The Heritage of Stone Spouts," UNESCO Kathmandu Newsletter 1 (Nov. 2000), 5.

Notes

1. The KathmanduValley was added to the World Heritage List in 1979 under the 1978 version of the Operational Guidelines meeting cultural criterion iii (be unique, extremely rare, or of great antiquity), criterion iv (be among the most characteristicexamples of a type of structure, the type representing,an important cultural, social, artistic, scientific, technological, or industrial development), and criterion vi (be most importantly associated with ideas or beliefs, with events or with persons, of outstanding historical importance or significance). 2. Mary Shepherd Slusser,Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley, vol. 1, (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1982), 146.

Engineering Services for Masonry Materials and Structures

* Failure Analysis * Repair Specification * Laboratory Research * Structural Analysis * Nondestructive Testing * Building Evaluation * Material Evaluation

The only consistent and reliable lime paint suitablefor historical walls.

LIME PAINT

FOR AUTHENTIC LUMINESCENT APPEARANCE

Atkinson-Noland & Associates, Inc.

2619

CALCEM?is designedto meet today's high performancerequirements. Visit our websiteat www.limepaint.com E-mail: info@limepaint.com 305-576-9070 Telephone: VoiceMail/Fax: 305-576-2399

Spruce

Street

l k

S

Boulder,CO80302 (303) 444-3620 Fax (303) 444-3239

http://www.ana-usa.com

This content downloaded from 202.52.244.42 on Thu, 8 Aug 2013 04:41:51 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Ancient Newari Water-Supply Systems in Nepal's Kathmandu ValleyDocumento6 pagineAncient Newari Water-Supply Systems in Nepal's Kathmandu ValleyvarishavipashaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 11 1636365451 7ijcseierddec20217Documento10 pagine2 11 1636365451 7ijcseierddec20217TJPRC PublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- ARNAVA Vo.7 .ChandraDocumento28 pagineARNAVA Vo.7 .ChandraNisha WayalNessuna valutazione finora

- ARNAVA - Vo.8 ChandraDocumento18 pagineARNAVA - Vo.8 ChandraNisha WayalNessuna valutazione finora

- Society and Environment in Ancient India (Study of Hydrology)Documento6 pagineSociety and Environment in Ancient India (Study of Hydrology)inventionjournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Stepwells Piplani2019Documento9 pagineStepwells Piplani2019Sahar ZehraNessuna valutazione finora

- Stepwells Piplani2019Documento9 pagineStepwells Piplani2019Hetansh PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Putali Barao - A Classic Example of Water Management System Under Yadavas of DeogiriDocumento13 paginePutali Barao - A Classic Example of Water Management System Under Yadavas of DeogiriMAHESHNessuna valutazione finora

- Village Tank Cascade Systems: A Traditional Technology of Drought and Water Management in Sri LankaDocumento36 pagineVillage Tank Cascade Systems: A Traditional Technology of Drought and Water Management in Sri LankaSudharsananPRS0% (1)

- 2018 Sinha LivingGhatsofVaranasiDocumento13 pagine2018 Sinha LivingGhatsofVaranasiNavin MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Irrigation SystemDocumento9 pagineIrrigation SystemDILRUKSHINessuna valutazione finora

- PatanDocumento12 paginePatanBigyan KcNessuna valutazione finora

- Material Authenticity in Tradition of Conservation in Nepal Sudarshan Raj Tiwari Professor, Institute of EngineeringDocumento11 pagineMaterial Authenticity in Tradition of Conservation in Nepal Sudarshan Raj Tiwari Professor, Institute of EngineeringRachita SubediNessuna valutazione finora

- Batangrande PDFDocumento43 pagineBatangrande PDFenrique19111975Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Traditional Community in The Chao Phraya River BDocumento15 pagineA Traditional Community in The Chao Phraya River BYên ChiNessuna valutazione finora

- 40 Socio CholaDocumento3 pagine40 Socio CholaVignesh Raj KNessuna valutazione finora

- Conservation Through Public ParticipationDocumento9 pagineConservation Through Public ParticipationS.K. RecruitingNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 - SynopsisDocumento26 pagineChapter 1 - SynopsisAnonymous Y9dgyXhANessuna valutazione finora

- 13 - Chapter 7 PDFDocumento84 pagine13 - Chapter 7 PDFVignesh VickyNessuna valutazione finora

- Arrm1 Fort ST Isable Adaptive Reuse (Chapter 1)Documento15 pagineArrm1 Fort ST Isable Adaptive Reuse (Chapter 1)Renzo DiwaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aesthetics of Hindu TemplesDocumento27 pagineAesthetics of Hindu TemplesUday DokrasNessuna valutazione finora

- Art and Culture Hub A Thesis Report: Akhila LDocumento54 pagineArt and Culture Hub A Thesis Report: Akhila LPRINCESS PNessuna valutazione finora

- The Legacy of Angkor WatDocumento23 pagineThe Legacy of Angkor WatudayNessuna valutazione finora

- Promenade It Is A Long, Open, Level Area Usually Next To River orDocumento12 paginePromenade It Is A Long, Open, Level Area Usually Next To River orsagar devidas khotNessuna valutazione finora

- Tecnologias Hidraulicas PrehispanicasDocumento19 pagineTecnologias Hidraulicas PrehispanicasMagui ValladaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Water Management in Uzbekistan Chapter Three PHDDocumento19 pagineHistorical Water Management in Uzbekistan Chapter Three PHDsameer lalNessuna valutazione finora

- Archae Logy and TourismDocumento7 pagineArchae Logy and Tourismbalacr3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Culture - Byju'sDocumento53 pagineCulture - Byju'sver.ayushiNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian TraditionDocumento25 pagineIndian TraditionIT 10 Amit GangwarNessuna valutazione finora

- 13 Chapter 7Documento84 pagine13 Chapter 7Naga RajNessuna valutazione finora

- Adalaj Stepwell - Gandhinagar's Historical MonumentDocumento4 pagineAdalaj Stepwell - Gandhinagar's Historical MonumentheenaNessuna valutazione finora

- LothalDocumento12 pagineLothalayandasmts100% (2)

- Report Writing N - 1630050500Documento3 pagineReport Writing N - 1630050500Ingrails School67% (3)

- Thanjavur SYNOPSISDocumento8 pagineThanjavur SYNOPSISKalees KaleesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pancha Rathas, The Five Stone Temples of The Mahabalipuram Site: Opportunity To Revive Its Lost Garden Heritage Through EcotourismDocumento27 paginePancha Rathas, The Five Stone Temples of The Mahabalipuram Site: Opportunity To Revive Its Lost Garden Heritage Through Ecotourismsowmya kannanNessuna valutazione finora

- BijkerDocumento16 pagineBijkerRamya SwayamprakashNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical and Environmental Study of Rani PokhariDocumento47 pagineHistorical and Environmental Study of Rani Pokharikhatryagrata100% (1)

- 2860-Article Text-5554-1-10-20210609Documento14 pagine2860-Article Text-5554-1-10-20210609Priya ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rebuilding From The Rubble - Kasthamandap TempleDocumento9 pagineRebuilding From The Rubble - Kasthamandap TempleIpshita KarmakarNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.1 Planning Principles Behind Chariot Route: History, Culture and Myth: Seto Machindranath Rath YatraDocumento12 pagine1.1 Planning Principles Behind Chariot Route: History, Culture and Myth: Seto Machindranath Rath YatraRajay BajracharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- South Indian Vernacular Architecture - ADocumento7 pagineSouth Indian Vernacular Architecture - AAzlaan AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Siddiqui 1986Documento27 pagineSiddiqui 1986Nikita KohliNessuna valutazione finora

- Note MAking Practice 11Documento5 pagineNote MAking Practice 11ankitamyloveNessuna valutazione finora

- Subsistence and Culture in the Western Canadian Arctic: A Multicontextual ApproachDa EverandSubsistence and Culture in the Western Canadian Arctic: A Multicontextual ApproachNessuna valutazione finora

- Document (5Documento3 pagineDocument (5Sugan UdhayakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- 438 869 1 SMDocumento14 pagine438 869 1 SMBagas yusuf kausanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2008 ALDENDERFER. 4,000 Años de Antigüedad de Artefactos de Oro en La Cuenca Del Titicaca, S de Perú (PNAS)Documento4 pagine2008 ALDENDERFER. 4,000 Años de Antigüedad de Artefactos de Oro en La Cuenca Del Titicaca, S de Perú (PNAS)David PalominoNessuna valutazione finora

- Sinha-Valderrama - Oracle OrchhaDocumento14 pagineSinha-Valderrama - Oracle Orchharaghav dhanukaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intersocietal Transfer of Hydraulic Technology in Precolonial South Asia: Some Reflections Based On A Preliminary InvestigationDocumento28 pagineIntersocietal Transfer of Hydraulic Technology in Precolonial South Asia: Some Reflections Based On A Preliminary InvestigationGirawa KandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Irrigation System in Tumkur District An Epigraphic Study PDFDocumento6 pagineIrrigation System in Tumkur District An Epigraphic Study PDFanjanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Discovery of New Rock Art Site in Talakona Valley in Chittoor District Andhra Pradesh - January - 2013 - 5764181995 - 3100212Documento3 pagineDiscovery of New Rock Art Site in Talakona Valley in Chittoor District Andhra Pradesh - January - 2013 - 5764181995 - 3100212Banu SreeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient HistoryDocumento52 pagineAncient HistoryVandanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lozada Mendieta 10093737 Thesis Volume 1Documento508 pagineLozada Mendieta 10093737 Thesis Volume 1Sandra CaicedoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kakatiya BriefDocumento2 pagineKakatiya BriefPudeti RaghusreenivasNessuna valutazione finora

- Indigenous Water Conservation Systems-A Rich Tradition of Rural Himachal PradeshDocumento4 pagineIndigenous Water Conservation Systems-A Rich Tradition of Rural Himachal PradeshM Abul Hassan AliNessuna valutazione finora

- 06jun Ancient Chinese Drilling PDFDocumento5 pagine06jun Ancient Chinese Drilling PDFshy_boyNessuna valutazione finora

- Status of Stone Spouts of Kathmandu ValleyDocumento5 pagineStatus of Stone Spouts of Kathmandu ValleyAmar TuladharNessuna valutazione finora

- Water Resource Management in Ancient Sri LankaDocumento36 pagineWater Resource Management in Ancient Sri LankaThamalu Maliththa PiyadigamaNessuna valutazione finora

- HERITAGEDocumento8 pagineHERITAGERavitej KakhandakiNessuna valutazione finora

- Recalling Ancient DwarakaDocumento7 pagineRecalling Ancient DwarakaVishnu AacharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Common ProblemsDocumento10 pagineCommon Problemshdd00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Error in HTTP RECEIVE 1 PDFDocumento3 pagineError in HTTP RECEIVE 1 PDFKumud RanjanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kiwis y Slog Web AccessDocumento39 pagineKiwis y Slog Web Accessshoki666Nessuna valutazione finora

- Salesforce Analytics Rest ApiDocumento289 pagineSalesforce Analytics Rest Apicamicami2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Assessment - Gap AnalysisDocumento7 pagineSample Assessment - Gap AnalysisKukuh WidodoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ferrous Metals: General Grade Cast IronsDocumento8 pagineFerrous Metals: General Grade Cast IronskkamalakannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Receptoras, Cableado y ConfiguraciónDocumento3 pagineReceptoras, Cableado y ConfiguraciónAntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Installation-SAPGUI For Windows For V750Documento16 pagineInstallation-SAPGUI For Windows For V75027296621Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainable Development Aditya SharmaDocumento9 pagineSustainable Development Aditya SharmaAditya Sharma0% (1)

- SS2Windows XP MicroStation V8i and Inroads Installation Instructions PDFDocumento26 pagineSS2Windows XP MicroStation V8i and Inroads Installation Instructions PDFmanuelq9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Seismic Resistant Structures (2018)Documento286 pagineSeismic Resistant Structures (2018)Hoàng Hiệp100% (3)

- PLC Vs Safety PLC - Fundamental and Significant Differences - RockwellDocumento6 paginePLC Vs Safety PLC - Fundamental and Significant Differences - Rockwellmanuel99a2kNessuna valutazione finora

- Sendspace Wizard Guide v1Documento29 pagineSendspace Wizard Guide v1arisNessuna valutazione finora

- Steel Interchange: How To Specify AESS Gusset Plate DesignDocumento2 pagineSteel Interchange: How To Specify AESS Gusset Plate Designhector diazNessuna valutazione finora

- Item Description Unit Qty. Rate Amount A. Sub Structure 1/1.0. Excavation & Earth WorkDocumento6 pagineItem Description Unit Qty. Rate Amount A. Sub Structure 1/1.0. Excavation & Earth WorkAbdi YonasNessuna valutazione finora

- Alexey Viktorovich ShchusevDocumento1 paginaAlexey Viktorovich Shchusevtanea_1991Nessuna valutazione finora

- Writing Your First Delphi ProgramDocumento63 pagineWriting Your First Delphi Programapi-3738566100% (1)

- Vmware Vsphere Powercli 5.8 Release 1 Reference PosterDocumento1 paginaVmware Vsphere Powercli 5.8 Release 1 Reference PosterPurushothama KilariNessuna valutazione finora

- Stone ColumnDocumento112 pagineStone Columnsriknta sahu100% (3)

- MORTH BT, CC, Causeway, BridgeDocumento247 pagineMORTH BT, CC, Causeway, BridgesrinivasparasaNessuna valutazione finora

- Newsletter 7750 SRDocumento8 pagineNewsletter 7750 SRCuongAbelNessuna valutazione finora

- Adv Materials Final PresenDocumento26 pagineAdv Materials Final PresenShee JaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tomb Dusk Queen PDFDocumento17 pagineTomb Dusk Queen PDFJamie PGR100% (6)

- CWNA Guide To Wireless LANs, Second Edition - Ch9Documento3 pagineCWNA Guide To Wireless LANs, Second Edition - Ch9NickHenry100% (1)

- Precision t1600 Spec SheetDocumento2 paginePrecision t1600 Spec SheetGongo ZaNessuna valutazione finora

- Highrise StructuresDocumento97 pagineHighrise StructuresumeshapkNessuna valutazione finora

- SPUN PILE WikaDocumento3 pagineSPUN PILE WikaCalvin SandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Steel Prices Middle EastDocumento1 paginaSteel Prices Middle EastSaher RautNessuna valutazione finora

- VSP G-Series Datasheet PDFDocumento2 pagineVSP G-Series Datasheet PDFMilton RaimundoNessuna valutazione finora