Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Mother Teresa: Angel of Mercy

Caricato da

alviarpitaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Mother Teresa: Angel of Mercy

Caricato da

alviarpitaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Mother Teresa: Angel of Mercy Mother Teresa, the charismatic nun who died September 5 at the age of 87,

was hardly a political figure in the conventional sense. But she had a politician's sense of issues and timing: she knew that in modern-day India, a nation of nearly a billion overwhelmingly poor people, the biggest issue of all was poverty. She drew larger crowds and invited greater affection than any politician -- testimony to her integrity and her humility, qualities conspicuous by their absence in the men and women who govern the world's largest democracy today. No soaring rhetoric for her, no appealing to atavistic impulses to take to the streets for humanitarian causes --just a simple, central message that resonated among everyday Indians: poverty is not noble nor acceptable, social justice does not automatically follow economic development. That message seized Indians and non-Indians alike because, notwithstanding the liberalization and progress that are fashionable to cite in this, the Subcontinent's 50th year of independence from the British colonial Raj, the chasm between haves and have-nots in India is so great that they might as well be living in two different countries. Mother Teresa herself would sometimes toss out a statistic or two, softly to be sure but chilling nevertheless: 300 million people living below the poverty line, millions more with options for economic mobility denied. Where were the jobs, she would ask, where was the large-scale investment in human development? What happened to the vision of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, India's founding fathers, for a just India? Powerful questions, articulated by a simple woman whose frail body packed more power than any other contemporary world figure. Like Gandhi, that power, of course, flowed from her spiritual wellspring. And like Gandhi, Mother Teresa was an unelected spokesman for the poor everywhere -- not simply highlighting their despair but also underscoring their hopes. At a time when majority-Hindu fundamentalism was on the rise and Muslims were becoming increasingly worried about their identity in supposedly secular India, no one dared to ask what business did a Christian missionary have representing India on the global stage. When she spoke, all India listened, the world took notice. No small feat that, especially when India's political stature has shrunk internationally in direct proportion to the growth of her social malaise and political corruption. Implicit in what Mother Teresa said was also an indictment of the international development organizations whose many billions had fattened bureaucracies but not sufficiently lifted the poor from their hovels. You did not have to be Indian to understand what she said: just ask the denizens of slums in dozens of Western countries that Mother Teresa visited and where her charitable organizations worked.

That is not to say Mother Teresa's judgment was unassailable on every issue. In a nation that adds 20 million people each year -- more than the entire population of Australia -Mother Teresa stubbornly resisted family planning programs. In keeping with her conservative Catholic beliefs, she was vehemently opposed to abortion, which is permitted in India. Some advocates of social development, such as U.N. bureaucrats, privately fretted that Mother Teresa was the biggest stumbling block to the international family planning movement, bigger than America's "right-to life" movement and Ronald Reagan in his heyday as U.S. president. Some accused her of being an ideologue, even though her prescription for India's population problem was predicated on the overriding belief that every child has the inalienable right to the pursuit of a full, happy life free from the malignancy of poverty. Her work in Calcutta's slums illustrated something that the high priests of global development often tend to overlook: in order to pull people out of poverty, it is important to first empower them with self-esteem and with the hope that change is always possible. Her missionary efforts exemplified the notion that, when confronted with Himalayan challenges such as traditional poverty, small steps are more effective than monumental antipoverty programs. And so, for Mother Teresa, it was one hovel at a time. In an age of self-promotion where even missionaries succumb to blandishments from publishers and lecture-circuit agents, Mother Teresa did not set out to be a celebrity. This wisp of a woman who was not Indian by birth did not set out to be a global spokesman for the poor of the Third World. But she recognized that, notwithstanding all the fancy talk in the world's financial salons about economic development and market forces, there were people out there whose lives remained mired in the sorry circumstances of their birth. And the reason why her constituency kept growing day by day -- in India, in the 127 countries of the developing world, and at the neglected edges of affluent industrialized nations -- was that the numbers of those dispossessed also kept growing: more than a third of the world's population of 5.8 billion lives in abject poverty today, in rich and developing states alike. Mother Teresa told us that the demographics of the dispossessed kept growing because the forces of globalization left more victims in their wake than beneficiaries. It was a sad, troubling message, but one that the mandarins of government and business might do well to heed. In a few days time, the barons of global finance and economic development will gather in Hong Kong for the annual meetings of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. They will cogitate over policy, and they will issue grave commentaries on sustainable development. They might do better to study how one small woman, in a simple white cotton sari, didn't bother much with reports and theories; instead, she simply went out into the world and changed the lives of millions.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Playing Djembe PDFDocumento63 paginePlaying Djembe PDFpbanerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- They’re Not Listening: How The Elites Created the National Populist RevolutionDa EverandThey’re Not Listening: How The Elites Created the National Populist RevolutionNessuna valutazione finora

- UCCP Magna Carta For Church WorkersDocumento39 pagineUCCP Magna Carta For Church WorkersSilliman Ministry Magazine83% (12)

- Chapter 7.1: Rockefeller Foundation: Origins of The Foundation System, The Rockefeller FoundationDocumento14 pagineChapter 7.1: Rockefeller Foundation: Origins of The Foundation System, The Rockefeller FoundationKeith KnightNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unheard Truth Poverty and Human RightsDocumento24 pagineThe Unheard Truth Poverty and Human RightsrazvanesquNessuna valutazione finora

- Deep Diversity: A Compassionate, Scientific Approach to Achieving Racial JusticeDa EverandDeep Diversity: A Compassionate, Scientific Approach to Achieving Racial JusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rich in Public Opinion: What We Think When We Think About WealthDa EverandThe Rich in Public Opinion: What We Think When We Think About WealthNessuna valutazione finora

- Archive Purge Programs in Oracle EBS R12Documento7 pagineArchive Purge Programs in Oracle EBS R12Pritesh MoganeNessuna valutazione finora

- Empire of Lies: The Truth about China in the Twenty-First CenturyDa EverandEmpire of Lies: The Truth about China in the Twenty-First CenturyValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (6)

- Kritvi - TOK Exhibition CommentaryDocumento6 pagineKritvi - TOK Exhibition CommentaryKritviiiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gods Solution to the Fiscal Cliff and How a Biblical Jubilee can Fix Our Economic WoesDa EverandGods Solution to the Fiscal Cliff and How a Biblical Jubilee can Fix Our Economic WoesNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations As Syndicates of Control - Rockefellers - Foundations As Control-16Documento16 pagineFoundations As Syndicates of Control - Rockefellers - Foundations As Control-16Keith KnightNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Vocabulary Vs IELTS VocabularyDocumento7 pagineSimple Vocabulary Vs IELTS VocabularyHarsh patelNessuna valutazione finora

- Oblicon NotesDocumento14 pagineOblicon NotesCee Silo Aban100% (1)

- Howard Thurman Lived From 1899 To April 10, 1981Documento18 pagineHoward Thurman Lived From 1899 To April 10, 1981Timothy67% (3)

- US. Peace Corps Tetun Language CourseDocumento305 pagineUS. Peace Corps Tetun Language CoursePeter W Gossner100% (1)

- Women Of Nazi Propaganda Love and Devotion of Women Fascinated by Hitler During the Third ReichDa EverandWomen Of Nazi Propaganda Love and Devotion of Women Fascinated by Hitler During the Third ReichNessuna valutazione finora

- Moral Challenges To GlobalizationDocumento3 pagineMoral Challenges To GlobalizationChrystal Jade J. AbadNessuna valutazione finora

- White Saviorism in International Development: Theories, Practices and Lived ExperiencesDa EverandWhite Saviorism in International Development: Theories, Practices and Lived ExperiencesNessuna valutazione finora

- Top German AcesDocumento24 pagineTop German AcesKlaus Richter100% (1)

- Marketing Movies: An Introduction To The Special Issue: Steven R. PritzkerDocumento3 pagineMarketing Movies: An Introduction To The Special Issue: Steven R. PritzkeralviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quizona Joseph Baes - CWTS Activity#3Documento7 pagineQuizona Joseph Baes - CWTS Activity#3JOSEPH QUIZONANessuna valutazione finora

- B G M A: Ack To Odhead - Arch / PrilDocumento6 pagineB G M A: Ack To Odhead - Arch / PrilDandavatsNessuna valutazione finora

- World Thinkers EbookDocumento42 pagineWorld Thinkers Ebookmerlin66Nessuna valutazione finora

- A New World - EumindDocumento3 pagineA New World - Eumindapi-541981758Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Snake That Ate Dinosaurs: Mangesh DahiwaleDocumento41 pagineThe Snake That Ate Dinosaurs: Mangesh DahiwaleSunil GawadeNessuna valutazione finora

- An Alternative NationDocumento10 pagineAn Alternative NationPrats KNessuna valutazione finora

- PopulismDocumento5 paginePopulismJunaid RamzanNessuna valutazione finora

- ACTIVITY 1 Analytical EssayDocumento2 pagineACTIVITY 1 Analytical EssayEloisa VicenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Democracy for the Haitian Crisis: Ideas for Political Reforms in HaitiDa EverandDemocracy for the Haitian Crisis: Ideas for Political Reforms in HaitiNessuna valutazione finora

- La Economia Politica de Nueva IndiaDocumento205 pagineLa Economia Politica de Nueva IndiadarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Commonwealth, Democracy and (Post-) Modernity: The Contradiction Between Growth and Development Seen From The Dalit Point of ViewDocumento6 pagineCommonwealth, Democracy and (Post-) Modernity: The Contradiction Between Growth and Development Seen From The Dalit Point of ViewKlv SwamyNessuna valutazione finora

- Taking Illiberalism SeriouslyDocumento4 pagineTaking Illiberalism SeriouslyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNessuna valutazione finora

- Politics Without Ethics Is A DisasterDocumento9 paginePolitics Without Ethics Is A DisasterGS Ethics100% (1)

- Going Back to Gettysburg: Autobiography of a Corrupt IndianDa EverandGoing Back to Gettysburg: Autobiography of a Corrupt IndianNessuna valutazione finora

- B. Shyam Sunder-Where Do Muslims Stand TodayDocumento5 pagineB. Shyam Sunder-Where Do Muslims Stand TodayH.ShreyeskerNessuna valutazione finora

- Henry Wallace - Century of The Common ManDocumento4 pagineHenry Wallace - Century of The Common ManMichael RyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay IdeasDocumento20 pagineEssay IdeasSahithi DakamarriNessuna valutazione finora

- There Is No Global Population Problem: Fall 2001Documento4 pagineThere Is No Global Population Problem: Fall 2001Maria RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay 1.0Documento1 paginaEssay 1.0Reymond DuluhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Blogs - Lse.ac - Uk-Book Review The History of Development From Western Origins To Global Faith by Gilbert RistDocumento3 pagineBlogs - Lse.ac - Uk-Book Review The History of Development From Western Origins To Global Faith by Gilbert RistTanya SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- True Liberation of WomenDocumento2 pagineTrue Liberation of WomenShirley KabirNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Right Global ConnectionDocumento129 pagineHuman Right Global Connectionkassahun argawNessuna valutazione finora

- The Persistence of Caste Indias Hidden Apartheid and The KhairlanjiDocumento178 pagineThe Persistence of Caste Indias Hidden Apartheid and The KhairlanjiHarshwardhan G1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Harvey Homily at Williams MemorialDocumento4 pagineHarvey Homily at Williams MemorialNeil ParsanlalNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3.3Documento7 pagineModule 3.3Dina BawagNessuna valutazione finora

- New Thought: The Hidden HistoryDocumento4 pagineNew Thought: The Hidden HistoryDeroy GarryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Democrats' Forgotten People: How the Trump Base Can Find A Home in the Democratic PartyDa EverandThe Democrats' Forgotten People: How the Trump Base Can Find A Home in the Democratic PartyNessuna valutazione finora

- Manifesto of The Hindustan Socialist Republican AssociationDocumento3 pagineManifesto of The Hindustan Socialist Republican Associationapi-3805005Nessuna valutazione finora

- Times in 2011Documento5 pagineTimes in 2011TimothyNessuna valutazione finora

- Games People Play - Summary & Review + PDF - Power Dynamics™Documento9 pagineGames People Play - Summary & Review + PDF - Power Dynamics™Rovin RamphalNessuna valutazione finora

- Witnesses, Villains, and HeroesDocumento24 pagineWitnesses, Villains, and Heroesbecky.bridgerNessuna valutazione finora

- (Ram Puniyani) Religion, Power and ViolenceDocumento333 pagine(Ram Puniyani) Religion, Power and Violencechitwanjit100% (1)

- Moral Challenges of GlobalizationDocumento11 pagineMoral Challenges of GlobalizationWyllow PapangoNessuna valutazione finora

- Citizens of the World: U.S. Women and Global GovernmentDa EverandCitizens of the World: U.S. Women and Global GovernmentNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 29 09 ExtremismDocumento4 pagine10 29 09 ExtremismJames BradleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ahmadinejad Speech To The UNDocumento4 pagineAhmadinejad Speech To The UNCaroline RobersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Emma Goldman The Individual Society and The StateDocumento9 pagineEmma Goldman The Individual Society and The StateAldo OjedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shashi Tharoor SpeechDocumento10 pagineShashi Tharoor SpeechmrnavneetsinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Success Through Positive Thinking: It is half empty or half full….is the way you look at itDa EverandSuccess Through Positive Thinking: It is half empty or half full….is the way you look at itNessuna valutazione finora

- Saving The American LeftDocumento8 pagineSaving The American LeftAlan BruceNessuna valutazione finora

- A New Consciousness For A World in CrisisDocumento5 pagineA New Consciousness For A World in CrisisMuhammad ZeeshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Midterm Rebyuwer 1Documento41 pagineMidterm Rebyuwer 1Azzmarie Nicole LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Management Science Letters: The Effect of Islamic Values On Relational Marketing BasicsDocumento8 pagineManagement Science Letters: The Effect of Islamic Values On Relational Marketing BasicsalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- CB ModelsDocumento23 pagineCB ModelsalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- India Jammu and Kashmir Earthquake MDRIN011drefDocumento5 pagineIndia Jammu and Kashmir Earthquake MDRIN011drefalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Internal Assessment MarksDocumento1 paginaInternal Assessment MarksalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Paper PDFDocumento9 pagineSample Paper PDFalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamentals of Strategic Management: Chapter OutlineDocumento18 pagineFundamentals of Strategic Management: Chapter OutlinealviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- ResPaper ICSE 1996 - SCIENCE Paper 1 (Physics)Documento7 pagineResPaper ICSE 1996 - SCIENCE Paper 1 (Physics)alviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- ResPaper ICSE 1997 - SCIENCE Paper 1 (Physics)Documento7 pagineResPaper ICSE 1997 - SCIENCE Paper 1 (Physics)alviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4real About 4realDocumento1 pagina4real About 4realalviarpitaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2202 Infantilization Essay - Quinn WilsonDocumento11 pagine2202 Infantilization Essay - Quinn Wilsonapi-283151250Nessuna valutazione finora

- Q4 SMEA-Sta.-Rosa-IS-HS-S.Y 2021-2022Documento38 pagineQ4 SMEA-Sta.-Rosa-IS-HS-S.Y 2021-2022junapoblacioNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading SkillsDocumento8 pagineReading SkillsBob BolNessuna valutazione finora

- Stock Control Management SyestemDocumento12 pagineStock Control Management SyestemJohn YohansNessuna valutazione finora

- Icecream ScienceDocumento6 pagineIcecream ScienceAnurag GoelNessuna valutazione finora

- EY Global Hospitality Insights 2016Documento24 pagineEY Global Hospitality Insights 2016Anonymous BkmsKXzwyKNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalogue Maltep en PDFDocumento88 pagineCatalogue Maltep en PDFStansilous Tatenda NyagomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Poea Rules and Regulations Governing RecruitmentDocumento8 pagineRevised Poea Rules and Regulations Governing RecruitmenthansNessuna valutazione finora

- A Note On RhotrixDocumento10 pagineA Note On RhotrixJade Bong NatuilNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample CVDocumento3 pagineSample CVsam_mad00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Working Capital Management by Birla GroupDocumento39 pagineWorking Capital Management by Birla GroupHajra ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical Activities: Ken Goldberg, VP Technical Activities Spring 2007, ICRA, RomeDocumento52 pagineTechnical Activities: Ken Goldberg, VP Technical Activities Spring 2007, ICRA, RomeWasim Ahmad KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Budget Anaplan Training DocumentsDocumento30 pagineBudget Anaplan Training DocumentsYudi IfanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dwnload Full Practicing Statistics Guided Investigations For The Second Course 1st Edition Kuiper Solutions Manual PDFDocumento36 pagineDwnload Full Practicing Statistics Guided Investigations For The Second Course 1st Edition Kuiper Solutions Manual PDFdavidkrhmdavis100% (11)

- Forum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismDocumento3 pagineForum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismLisel SalibioNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety Management in Coromandel FertilizerDocumento7 pagineSafety Management in Coromandel FertilizerS Bharadwaj ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

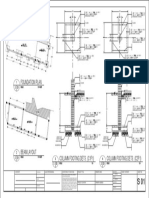

- Foundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSDocumento1 paginaFoundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSJayson Ayon MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Services Marketing-Unit-Ii-ModifiedDocumento48 pagineServices Marketing-Unit-Ii-Modifiedshiva12mayNessuna valutazione finora

- The Identification of Prisoners Act, 1920Documento5 pagineThe Identification of Prisoners Act, 1920Shahid HussainNessuna valutazione finora

- PMMSI Vs CADocumento1 paginaPMMSI Vs CAFermari John ManalangNessuna valutazione finora

- The Basics of Effective Interpersonal Communication: by Sushila BahlDocumento48 pagineThe Basics of Effective Interpersonal Communication: by Sushila BahlDevesh KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic and Product Design Considerations in MachiningDocumento29 pagineEconomic and Product Design Considerations in Machininghashir siddiquiNessuna valutazione finora

- Revalida ResearchDocumento3 pagineRevalida ResearchJakie UbinaNessuna valutazione finora