Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Adam Phillips Info

Caricato da

dbhingstDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Adam Phillips Info

Caricato da

dbhingstCopyright:

Formati disponibili

theartsdesk Q&A: Psychoanalyst Adam Phillips The leading psychoanalyst talks fashion, therapy and about becoming an art

curator by Fisun GnerSaturday, 17 April 2010 http://www.theartsdesk.com/visual-arts/theartsdesk-qa-psychoanalyst-adam-phillips Adam Phillips: the sceptical psychoanalyst Born in 1954, Adam Phillips is a leading psychoanalyst, literary critic and author. For 17 years he worked as a child psychotherapist in the NHS before moving into private practice to work with adults. As well as being a selfconfessed "sceptical" psychoanalyst, he is also known as something of "the literati's analyst of choice". His many, often playfully titled books have included The Art of Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life (1993); On Flirtation: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Uncommitted Life (1995); and On Kindness (with Barbara Taylor, 2009). In 2006 he edited the New Penguin edition of the Sigmund Freud Reader. In collaboration with Artangel, and partner and fashion curator Judith Clark, he has co-curated The Concise Dictionary of Dress, an evocative art installation that "redescribes dress in terms of anxiety, wish and desire". He lives with Clark in Notting Hill, London. Fisun Gner: Why The Concise Dictionary of Dress? ADAM PHILLIPS: Judith and I both had the idea for it. We wanted it to partly be about the notion of captions and partly about what needed to be said about objects, so the original idea was to call it Words of Clothes. Then we became more interested in classification and storage. The Dictionary... seemed obvious, and Ive always been interested in dictionaries, and it seemed a very interesting idea to me to write an unconventional kind of dictionary. I wanted to look at them as a kind of genre, to see in what sense dictionaries curated words, in the way that dress might be curated, and in what sense they stored words. But the real truth, of course, is that things come out in the making - I dont sit there with all these ideas and then write them down. They appear as I write them. So are you familiar with the history of dictionaries? I know a bit about it, yes, though Im not scholarly. Im not interested in reading like that, but over the years Ive read bits and pieces about dictionaries and I read dictionaries sometimes. Have you always read dictionaries? No, I havent. You wrote an essay recently on excess and why were so drawn to it [in the Guardian]. Fashion is a celebration of excess and you could argue that its a celebration of a kind of hedonism. But dictionaries are the opposite of excess, in that they pin down and confine. Yes, theyre about limits. But I dont know if fashion is as hedonistic as it looks and I dont mean by that that there isnt a huge amount of pleasure in it. Hedonism is a cover story for it being far more interesting than that. And one of the things the exhibition is about, and I say this in the essay, is that it says fashion designers are at their best as kinds of historians: theyre very knowledgeable, either tacitly or explicitly, about the history of dress, and they incorporate things from the past into their clothes. But, of course, fashion is also about pleasure, it is about excess, and so is language in a way. There are parallels - and this may sound terribly banal - between clothes as a language and words as a language, and thats also an idea thats explored in the exhibition. So, in one sense fashion is fun, but like a lot of so-called fun its doing a lot of other things, too. I suppose both can obfuscate, in the way that fashion presents an armour and so does language. Exactly. Theyre both languages. Theyre both ways of saying things and not ends in themselves. I really like this quote from the catalogue essay you wrote for the exhibition. The reason that people are disdainful of fashion is that they fear that many of the things they value most in their lives may be more like fashion than anything else. Does that really strike you as true? Yes, it does. Growing up depends on continuity. In order to become the adults that we are sitting in this room there have been some continuities in our lives. So, for example, no child would want to think that its parents are transient. Indeed, children depend upon a quasi-magical belief that their parents wont die, that they will, in a certain sense, see them through. One of the disjunctions between childhood and adulthood is that when you become an adult your attachments to other people are based on the knowledge that you dont know how long theyll last. Whereas we begin as children with the wishful belief that our parents will last. So theres a disjunction and fashion highlights it.

Fashion really highlights the way in which things we love pass and are transient and it also highlights how we always want the next best thing. So it exposes something about the way we desire and that I think is very, very interesting. Theres a fear that lots of the things that matter most to people, that they previously thought mattere d most because they lasted, may actually matter most to them for more interesting reasons than the fact that they last. Fashion forces us to look at why things, very intensely and for very short periods of time, might matter to us. And I think its very interesting how opinion divides about fashion, that some people are straightforwardly and wholeheartedly into it and love it and are intrigued by it. And then theres a sort of high -culture end of this, which is either rather disdainful of it - as if theres something superficial about being interested in it - or they want to incorporate it in academic study. Or perhaps one of the real reasons that people fear or dislike fashion is that fashion people are kind of alarming and "exotic". Theres nothing reassuring about fashion because the people who belong to that world belong to a very exclusive club and the rules keep changing. I think its inevitable in this culture, which is partly based on envy, that people involved in fashion, from the outside, are so embroiled in capitalism in one sense. Like bankers, they become sort of symbols of what is supposedly wrong with the world as it is at the moment. My guess is that people in fashion are rather like accountants and psychoanalysts and lawyers and judges - theyre very varied and we shouldnt jump to conclusions about what theyre like without knowing them. It also may be true that people go into fashion from a huge diversity of motives. But again I think theres an understandable fear of glamour. And the fea r of glamour is to do with the fear of what it conceals. I think people in fashion, people who are designers, say, are often the ones to, publicly at least, dissociate themselves from the industry: you hear them say how it's other people in the industry who are shallow, not them. For instance, there was a lot of talk when Alexander McQueen died that he was not a typical fashion person, that he was an artist. People want to locate shallowness somewhere, dont they? The shallow must be somewhere else. And similarly the distinction of fashion and art, as if artists are the real thing, of which fashion people are some poor imitation. Whereas it seems to me that these are not very useful or interesting ways of looking at things. One of the things we try to do in this exhibition, is to suggest that fashion might be more interesting than it looks. Its not an attempt to say, Isnt fashion wonderful if you look at it this way. Its much more a way of saying that one of the things that fashion designers are, are historians. Theyre conserving things from the past. But, of course, things from the past have a very short life sometimes. Was it Artangel who approached you? Artangel approached me in the first instance about whether there was something I would like to do. Judith and I had been talking about this project for some time and so it seemed to fit with the kind of thing Artangel did. So how long was it in the making? Oh years. Years from Judith and I first discussing it as a possibility. When we discussed it to begin with there was no obvious way in which it could become an exhibition. Then Artangel approached me and we started meeting with Michael Morris [Artangel director]. He was really important in this collaboration, and it was through talking with him for at least two years that it eventually came to be what it is. So it had a long period of coming together. Im amazed that they ever manage to get anything off the ground. Artangel projects often seem to take years. You have to have such a belief in the future. Its a wonderfully optimistic thing. Your own writing has been described as ludic and elusive and intellectually slippery, so the opposite of a dictionary. Do you think your writing or writing style defines who you are? It defines me as a writer. It seems to me that its very hard to make links, really, between the way someone writes and the way they are in the world, with their friends, family. And you can only write in the way you write. So for me, writing is an opportunity - I didnt think of this consciously, but it seems to be true retrospectively - to perform oneself in a certain way. But like everyone whos a writer I dont really get to choose my words, I mean to some extent I do, but the writing I do feels like automatic writing. I sit down, it writes itself. Is that how you describe the process? Pretty much, yes. Its mostly automatic writing and then I chip in with a few suggestions.

Youre very lucky. Yes, its very easy. Thats the point about it. Its extremely easy when you can do it, and when you cant do its impossible. And I love writing, its a pleasure. I only do it because its a pleasure. But it must have taken a few years to feel comfortable with that style of writing. Yes, and you have to keep doing it. But I presume you keep doing it because you enjoy it, and thats true for me. Because I can never earn my living as a writer, which has freed me in a way just to go on writing in the way that I wanted to. Yes, but you must also be incredibly disciplined. I know it looks like that, but it doesnt feel like that. A reviewer said he always reads your books twice in order to get what you were saying and even then he isn't sure what you were saying. Its as if youre framing a series of propositions but whatever is goi ng on is kind of outside this frame. Thats not exactly the intention, but Im certainly aware of the fact I want people to enjoy the experience of reading. I dont want them to come out of it knowing what I think about X or knowing my theory of Y. I want people to have their own thoughts in the reading, so for me its a success when people say, I really enjoyed this, but Ive no idea what it was about, not because I want to mystify them but because theyve had an experience in the reading that they felt was worth having. I want to write sentences that I really like, that seem to me to be interesting. And if they engage with other people, that is wonderful. I dont want to inform you of something by reading the book, but you might have your own thoughts while you read it and that would be good. And the exhibitions not dissimilar, in that the exhibition plays off the relationship between whats evocative and whats informative. And I think Im more interested in things that are evocative than things that are informative. Did you and Judith decide together what objects were going to appear in the exhibition? The installations are very much her work. We discussed what words we might use and I did the definitions. And then she used the definitions as prompts, so not remotely like instructions, because my words arent instructive. But she used them as an evocative prompt, to see what installations she felt would be pertinent and interesting, I havent seen the objects yet, but the press release has on it a selection of images, and many of these are French 18th-century objets d'art its like Madame Pompadours cabinet of curios. Whats difficult about this is, of course, that you cant see the objects until you see them. Not that I want to mystify this, but theres got to be an element of surprise about it and the unexpected. When you see them you will see - and Ive only seen four of the installations myself so far - that they are very much combinations, because objects from different periods and of different materials are combined. They are not fixed to one century, but there are things of the 18th century in it. They come, I presume, from Judiths repertoire of images. Is precision important to you? Yes, very important. But you know the thing that Oscar Wilde said about not wanting to fall into careless habits of accuracy? I think that the trouble with precision and accuracy and scrupulousness is that they become conventionalised very quickly. It as though we forget that these are fantasies of rigour, if you see what I mean. Peoples impressions of each other can be very, very precise, while also vague. Dreams are very precise, in the meanings they can generate, but they can be very all-over-the-place and bizarre and surreal. I feel ambivalent about psychoanalysis Youve been labelled a sceptical psychoanalyst. What does it mean to be a sceptical psychoanalyst? It means something very simple, in a way. I love psychoanalysis and Im very interested in it, but its not a religion. And by that I mean, its not something about which one should have unquestioning faith. One of the things Freud makes fundamental is the idea that we are ambivalent animals, which means that we love and we hate, so wherever we hate, we love and vice versa. Given thats true, its very odd that psychoanalysts dont admit to being ambivalent about psychoanalysis. Well, I feel ambivalent about psychoanalysis. There are lots of things I love and value about it, but I have doubts about it. And it seems to me that both things need to be kept in play for it to be valuable. Otherwise it becomes a cult, and it should be the opposite, the antidote to a cult. Thats interesting you should say that because I did read someone who did a profile of you describe you as a figure who attracts a cultish following - that you excite a kind of dedicated devotion. A bit like a Pied Piper figure.

I think there are several things in that statement. One is that people in this culture are very ambivalent about psychoanalysts. I think also that in the period in which I have written my books, very few people have also been writing psychoanalytic books that are reviewed in the Sunday papers. So its something to do with popularisation. And it also seems to me that its inevitable that if you do anything at all forceful people will either love it or hate it or both. And I write books for the people who love the books and f or people who hate them. Its not a cultic thing. And I dont tremendously mind, beyond a certain circle of my friends or peers, what people think about the books, but it does matter to me that people are engaged by them. I do find it interesting and amusing that people use these kinds of words about me when theyve never met me. They dont know you, but I suppose what this writer was trying to suggest is that a kind of cult has grown around you, personally, rather than the ideas you discuss in the books Well, if it has I dont know about it. Thats all I can say. It seems a little excessive. In psychoanalysis you take things apart and then you put them together and create some kind of story. Is that a good description, or definition, of psychoanalysis? Yes, though the only thing is that it makes it sound slightly too analytic, too taking things apart. It doesnt take things apart so much as redescribe them and look at them from different points of view, such that new stories can be formed out of them. Peoples childhood isnt taken apart, people talk about the things that preoccupy them and a psychoanalyst would redescribe those same things from a different perspective and see what the person makes of that. Its not indoctrination; its a collaborative retelling of a life story. It's important that psychoanalysis is realistic But it has to be a helpful retelling, otherwise the process would be destructive. There are two different things here. The project is that it is useful and helpful, thats certainly true. But its also true that people can have lives in which things have happened to them, or theyve done things, which are irredeemable. So those things have to be seen as they are. So its helpful where it can be, and realistic where it cant be hel pful. But its much more important to me that its realistic than that its helpful. So you dont see psychoanalysis as an attempt to achieve a kind of redemptive state? No, its anti-redemptive. Its anti-redemptive and in a way its a critique of all those ideas in the culture. So its really not about curing people, its about something much more realistic than that. If its not about redemption, would you perhaps describe it as an attempt as some kind of reconciliation? Not necessarily. It could be that, but then again parents do things to children, and indeed children do things to parents that are unforgivable. So its not about self-forgiveness, either? No, its not. Its not about anything specific. I dont want to be too vague about this - those things you mention it can include, other than redemption - but it doesnt have a purposive intention to make those happen. Forgiveness may come out of psychoanalysis, but it would not be the intention of analysis to create forgiveness in a person, or to make them more forgiving, because its a more open-ended exploration than that. The thing is, that you cant know what will happen as a consequence of entering into psychoanalysis. Thats why analysts simply have to be honest about the sense in which psychoanalysis is a risk. Of course, I value it because Ive done a lot of it. Im not selling something that I know to be false or dangerous, but it is risky. Have you become more sceptical over the years? No, but Ive become more aware of the limitations of t herapies in general. I still think for some things, and for some people, psychoanalysis is the best thing going. But all the therapies are good for some people. What type of people is psychoanalysis good for? Theres not a type. Well, is it particularly good for articulate people? No, no, absolutely not. I worked for 17 years in the health service and worked in clinics in the poorest parts of London, where lots of the children I saw had parents with hardly any schooling at all and its as effective. Its an absolute fabrication the idea that psychoanalysis is a sort of middle-class stronghold. All sorts of people gain from being listened to.

Maybe we have this idea because its so expensive But that isnt true, either, and indeed child psychotherapy was available in the health service, it was free. Its amazing how powerful being listened to is. Is working with children easier or harder than working with adults, or does that question not apply? It does apply, but children are much better at psychoanalysis than adults are, because adults are, by the time they have become adults, much more defensive. Theyve elaborated their defences over a very long period of time. Its not that children dont have defences, because they do, but most children have a very strong sense early on of what theyre interested in and what theyre not interested in. And theyre more fun. Childrens capacity for pleasure is far greater than adults - not all adults, but children are real Darwinian pleasure-seekers. So its much more fun, which isnt to say it isnt fun working with adults. But there are more laughs working with children. Its also, in some ways, more disturbing, because children are also, by the same token, so much more vulnerable. I believed I could listen to anything, but when I had my own children I found it a lot more painful So why did you move away from child therapy? There were several reasons. One was that the bit of the health service I was working in was collapsing. We were being managed by people who had no idea what we were doing, and that was terrible. I also found it much more difficult when I had my own children to listen to the terrible things that happen to children. When I started, in a kind of internal hero myth, I believed I could listen to anything, But when I had my own children I found it a lot more painful. How many children do you have? Three. So there was that, and thats not incidental in this. But it was very, very dismaying for me to leave the health service, because I went into child psychotherapy because I was very interested in it and partly because it was available on the health service. It was a genuinely available therapy. And by the time I left it was a very rundown thing. It was very depressing and disillusioning. I often talk to a lot of artists who say the same thing, that once they have children their work changes profoundly, as if theres a rupture: before children and after. But still, you continue to be very productive in many areas, as a writer and with your day job, and now in the art world. Do you ever suffer from that writers disease of procrastination? I dont experience myself as disciplined - Im not involving myself in some regime to make myself do things. I can only write when I can write. Of course, I do psychoanalysis in a disciplined way: people come on the hour, it lasts a certain amount of time, it requires a certain skill. But I write because its a pleasure. I have got an appetite for it, so in that sense theres an ease about it. I find doing psychoanalysis much harder than writing. I think that if I found writing hard I wouldnt do it. I wouldnt have the tenaciousness. Was it fun working with someone you live with and have an intimate relationship with? I thought it wouldnt be, but, yes, it was actually a lot of fun. The Concise Dictionary of Dress is at Blythe House, London W14 from 28 April

The New Statesman Profile - Adam Phillips Nicholas Fearn http://www.newstatesman.com/200104230011 Published 23 April 2001 The celebrity shrink writes beautiful prose, enjoys the acclaim of the stars - but has he ever helped anyone? Adam Phillips profiled Who is Adam Phillips? Why does he seem to inspire such fervent admiration and yet such hostility? Little known outside literary London but widely respected, Phillips has been described as the best psychotherapist in Britain and one of our greatest contemporary psychoanalytic thinkers. To Adam Mars-Jones, he is "the closest thing we have to a philosopher of happiness". To John Banville, he is "one of the finest prose stylists at work in the language, an Emerson of our time". Alain de Botton recently confessed that Phillips was the only author to whom he had ever written a fan letter. But to his critics, who prefer to remain anonymous, Phillips is little more than a charlatan around whom an alarming cult of personality is developing. Certainly, when I began researching this profile, I was surprised at how many people called to speak about Phillips (strictly off the record), people I neither knew nor had approached. One afternoon, I was kindly contacted by a former partner of Phillips's. She seemed surprised when I told her that I was not writing a long article about him for a Sunday colour supplement. Many people, it seems, want to know Phillips, want to be part of his world. Among the luminaries to have entered his Notting Hill consulting room are the novelists Will Self, Tim Lott and Hanif Kureishi. Writers do not often put their faith in analysts, trusting themselves to have a better understanding of the psyche than a suspect branch of the medical profession. When a writer goes to see Phillips, however, he is meeting an equal. Psychology was once distrusted because it was thought too young to be taken seriously. It was, to a real science of character, what alchemy was to chemistry. Freud himself protested that psychology was born middle-aged - the stage of alchemy having consisted in the work of poets. While orthodox psychoanalysts struggle to maintain a veneer of scientific respectability, Phillips has become Britain's most celebrated exponent of psychoanalytic writing for the literary value of his work. "I read psychoanalysis as poetry," he has said. "So I don't have to worry about whether it is true or even useful, but only whether it is haunting or moving or intriguing or amusing." Phillips has intrigued and amused his own readers in a succession of critically acclaimed essays. Like a good clinician in the consulting room, he never dictates or harangues, but hints at hidden meanings and points of interest. In his early works - On Flirtation, On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored - he wrote of topics such as tickling and cross-dressing with the same care he lavished on love and death. Packed with maxims and allusions to philosophy and letters, they attracted admirers whose eulogies jostle for position on the back covers of his paperbacks. The one dissenting voice came from within his own profession. Reviewing On Flirtation in the British Medical Journal, Anthony Daniels, a consultant psychiatrist at All Saints Hospital, Birmingham, complained that "paragraph after paragraph conveyed little or no sense to me, and I could detect no difference in meaning when I converted some of his affirmative sentences into their negatives". All praise was suspended briefly after the publication of Monogamy, a book of aphorisms, in 1996. Despite containing such gems as "Masturbation is not only safe sex, it is safe incest" and "A couple is a conspiracy in search of a crime. Sex is often the closest they can get", the book brought accusations of pretentiousness. Carmen Callil wrote in the Telegraph that it "oozes the arrogance of a man no one has contradicted for too long". Normal service has since resumed, although Phillips's latest volume, Houdini's Box, is a below-par study of escapism that achieves neither the wit nor depth of The Beast in the Nursery or Darwin's Worms. On the fly-leaf, Alain de Botton puffs him as "the finest essayist working in Britain". I asked de Botton about his interest in Phillips. "If there is a cult of Adam Phillips, it is not a cult of personality in any way," he said. "If you appreciate his books and read them seriously, this doesn't mean you will want to meet him at a party. He is a writer, not a personality." This is just as well, because Phillips never attends parties. This is not for want of invitations. He does little to seek out the fame that he enjoys in the literary world. He claims not to make money from his books, but they sell in

respectable numbers, and it has to be remembered that psychoanalysts employ notoriously high standards when judging the size of cheques. Interviewers are apt to be mesmerised by his steady gaze, cool demeanour and the good looks that survive his uncanny resemblance to Bob Dylan (one female journalist was moved to describe him as "the shrinking woman's crumpet"). Phillips was born in Cardiff in 1954, the grandson of Jew- ish immigrants who came to Britain to escape persecution in Poland and Russia. His parents sent him to a Bristol public school and he went on to study English at Oxford University. He left with a third-class degree. For 18 years, until 1995, he worked in the National Health Service, becoming principal child psychotherapist at Charing Cross Hospital. He left to concentrate on writing and his private practice. He lives with the writer and critic Jacqueline Rose and their daughter, Mia, a Chinese orphan whom the couple adopted six years ago. Phillips is said to be a doting father, and his bond with his daughter has made him feel uncomfortable, some say, treating children. One journalist who knows several former patients of Phillips's professes never to have heard of anyone getting better as a result of his treatment. If this is true, his popularity has not suffered as a result. There is also a question of what "getting better" means - a subject on which Phillips has controversial opinions. He once said: "If people leave my room feeling OK, then I have failed. I have just reproduced a little enclave of well-being." In The Beast in the Nursery, he wrote: "The reassuring notions of so-called insight - the how-I-came-to-be-who-I-am stories - are a poor substitute for people's capacity to transform their worlds. Psychoanalysis should not be promoting self-knowledge as a consolation prize for injustice." He recoils from the assumption of many therapists that life must necessarily be a process of dealing with disillusionment. Therapy, he writes, "teaches us to accept frustration, to tolerate dissatisfaction. It can teach you to bear too much." The notion that therapy has promoted, rather than abolished, stoicism seems absurd; but there is method in his treatment of madness. Phillips has a refreshing disdain for the snobbery of suffering, the respect for pain that supposedly makes it worth enduring. To him, the purpose of psychoanalysis is less to metabolise this experience than to show how it can be made a source of creative action. Phillips is content to suggest his ideas rather than establish them. He will simply raise the question of why the negative aspects of an individual's character are taken to be more revealing than the positive ones. Phillips is more than ready to promote play and gaiety, and his reluctance to pathologise otherwise innocuous personality traits is admirable. Yet by relying on aphorisms and asides to make his case, he takes up an attitude rather than an argument. He has written, in Promises, Promises, that he thinks of literature and psychoanalysis as "forms of persuasion". Accordingly, he avoids the therapeutic vocabulary - of "shyness", "depression" and "low selfesteem" - in favour of "language that's more productive, language that goes on to produce more language". In Phillips's view, the main requirement of therapy is that it be interesting, and if nothing remarkable exists then it is necessary to invent it. In Houdini's Box, he wrote: "Psychoanalysis, of course, does not reveal what people are really like, because we are not really like anything; psychoanalytic treatment is productive of selves, not simply disclosing selves that have been there all the time waiting to be discovered, like Troy or Atlantis." Psychoanalysis seeks to cure by helping us to understand how we represent our lives. If this is to have a chance, Phillips knows that it had better come up with pretty compelling representations of its own, because they must compete with the actual events, pleasures and pains. With his literary talents, he is singularly well-equipped to help construct these representations. However, because in Phillips's work psychoanalysis does not hold out the prospect of coming to know or understand things that are true about oneself and others, it becomes, in the words of one academic, a "cultural experience rather than a clinical one". Oliver James remarks that Adam Phillips's books are "beautifully written in a grotesquely badly written sector of the literary world". This they undoubtedly are, though whether they are enough to make a mark on posterity is another matter. Wittgenstein and Nietzsche constructed aphorisms, but they also had a body of great theoretical work to support them. The dictionary of quotations makes a poor history book in which to be remembered.

Nicholas Fearn's Zeno and the Tortoise: how to think like a philosopher will be published by Atlantic Books in September

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Lite Touch. Completo PDFDocumento206 pagineLite Touch. Completo PDFkerlystefaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Flesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingDocumento14 pagineFlesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingRob ThuhuNessuna valutazione finora

- Skin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroDocumento15 pagineSkin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroAnonymous Dgn6TCsbB100% (1)

- Agamben, Giorgio - Taste PDFDocumento88 pagineAgamben, Giorgio - Taste PDFBurp FlipNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Limits of EmpathyDocumento20 pagineOn The Limits of EmpathyNayeli Gutiérrez HernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- Phillips, Attention SeekingDocumento5 paginePhillips, Attention SeekingAdriana Scaglione0% (1)

- Jean Baudrillard - The Global and The UniversalDocumento5 pagineJean Baudrillard - The Global and The Universalakrobata1100% (1)

- Revolution in Poetic Language: by Julia KristevaDocumento25 pagineRevolution in Poetic Language: by Julia KristevaMalik AtifNessuna valutazione finora

- Catastrophe Claims Guide 2007Documento163 pagineCatastrophe Claims Guide 2007cottchen6605100% (1)

- Arbus Aperture MonographDocumento7 pagineArbus Aperture MonographeltonfldfNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview With Jamieson WebsterDocumento12 pagineInterview With Jamieson Webstermatthew_oyer1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society, or Why Sociologists and Others Shold Take Utopia More SeriouslyDocumento22 pagineThe Imaginary Reconstitution of Society, or Why Sociologists and Others Shold Take Utopia More SeriouslyJen SevenNessuna valutazione finora

- Paolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'Documento6 paginePaolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'dallowauNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarat Maharaj Method PDFDocumento11 pagineSarat Maharaj Method PDFmadequal2658Nessuna valutazione finora

- Guattari's Aesthetic Paradigm: From The Folding of The Finite/Infinite Relation To Schizoanalytic MetamodelisationDocumento31 pagineGuattari's Aesthetic Paradigm: From The Folding of The Finite/Infinite Relation To Schizoanalytic MetamodelisationnatelbNessuna valutazione finora

- An Interview With Frans de Waal PDFDocumento9 pagineAn Interview With Frans de Waal PDFMager37Nessuna valutazione finora

- Authenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingDocumento28 pagineAuthenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingMaria Laura VillarrealNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosa SelfInterpretationDocumento37 pagineRosa SelfInterpretationCamilo VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- Andreas Gursky and The Contemporary Sublime PDFDocumento15 pagineAndreas Gursky and The Contemporary Sublime PDFJavier Basualdo C.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge LTD: Toward a Social Logic of the DerivativeDa EverandKnowledge LTD: Toward a Social Logic of the DerivativeNessuna valutazione finora

- Theorizing Affect and EmotionDocumento7 pagineTheorizing Affect and EmotionRuxandra LupuNessuna valutazione finora

- Pli 13 FoucaultDocumento242 paginePli 13 FoucaultMax Stirner100% (1)

- Judith Butler - Torture and The Ethics of PhotographyDocumento17 pagineJudith Butler - Torture and The Ethics of PhotographyRen TaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bluck, 1953, The Origin of The Greater AlcibiadesDocumento8 pagineBluck, 1953, The Origin of The Greater AlcibiadesÁlvaro MadrazoNessuna valutazione finora

- Graeber On StupidityDocumento13 pagineGraeber On StupiditySergio Villalobos100% (1)

- DerridaDocumento13 pagineDerridaKanika BhutaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Brandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondoDocumento32 pagineBrandon Labelle Interview by Anna RaimondomykhosNessuna valutazione finora

- Hal Foster - Towards A Grammar of EmergencyDocumento14 pagineHal Foster - Towards A Grammar of EmergencyEgor Sofronov100% (1)

- Ahmed (Happy Objects), Massumi (Politics of Threat), Probyn (Shame) - Unknown TitleDocumento33 pagineAhmed (Happy Objects), Massumi (Politics of Threat), Probyn (Shame) - Unknown TitleSydney TyberNessuna valutazione finora

- Transgression, Decay, and eROTicism in Bernard Tschumis Early Writings and ProjectsDocumento13 pagineTransgression, Decay, and eROTicism in Bernard Tschumis Early Writings and Projectsshumispace319Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sophia Volume 50 Issue 4 2011 (Doi 10.1007 - S11841-011-0276-Y) Matthew Lamb - Philosophy As A Way of Life - Albert Camus and Pierre Hadot PDFDocumento16 pagineSophia Volume 50 Issue 4 2011 (Doi 10.1007 - S11841-011-0276-Y) Matthew Lamb - Philosophy As A Way of Life - Albert Camus and Pierre Hadot PDFSepehr DanesharaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vangelis AthanassopoulosDocumento10 pagineVangelis AthanassopoulosferrocomolusNessuna valutazione finora

- Bourriaud Relational AestheticsDocumento18 pagineBourriaud Relational AestheticsLucie BrázdováNessuna valutazione finora

- Ordinary Affects by Kathleen StewartDocumento3 pagineOrdinary Affects by Kathleen Stewartrajah418100% (1)

- Manning - For A Pragmatics of The Useless ANNOTATEDDocumento385 pagineManning - For A Pragmatics of The Useless ANNOTATEDRodolfo Marchetti LorandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Womanliness As A Masquerade Joan+RivièreDocumento11 pagineWomanliness As A Masquerade Joan+RivièreGabiCaviedes100% (1)

- The Authority to Imagine: The Struggle toward Representation in Dissertation WritingDa EverandThe Authority to Imagine: The Struggle toward Representation in Dissertation WritingNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview With Jamieson Webster On BadiouDocumento11 pagineInterview With Jamieson Webster On BadiouzizekNessuna valutazione finora

- Foucault's Aesthetics of ExistenceDocumento8 pagineFoucault's Aesthetics of ExistenceAlejandra FigueroaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Performances of Sacred Places: Crossing, Breathing, ResistingDa EverandThe Performances of Sacred Places: Crossing, Breathing, ResistingSilvia BattistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Adam Phillips pARIS rEVIEWDocumento20 pagineAdam Phillips pARIS rEVIEWNacho DamianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dialectical ImageryDocumento14 pagineDialectical ImageryPaiyarnyai JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- ANDC TROPHY-Liminal SpaceDocumento8 pagineANDC TROPHY-Liminal SpaceMegha PanchariyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Martin Buber & PsychotherapyDocumento8 pagineMartin Buber & PsychotherapytorrenttinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Boy by Roald DahlDocumento24 pagineBoy by Roald DahlGavoazi LiviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Simon Sheikh: Spaces For Thinking. 2006Documento8 pagineSimon Sheikh: Spaces For Thinking. 2006Miriam Craik-HoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Malabou Plasticity and ElasticityDocumento9 pagineMalabou Plasticity and ElasticityMasayoshi KosugiNessuna valutazione finora

- Deleuze-Coldness and CrueltyDocumento67 pagineDeleuze-Coldness and CrueltyJana SteingassNessuna valutazione finora

- Visceral GeographiesDocumento11 pagineVisceral GeographiesmangsilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surrealpolitik: Surreality and the National Security StateDa EverandSurrealpolitik: Surreality and the National Security StateNessuna valutazione finora

- Against Interpretation Essay Susan Sontag MkiDocumento7 pagineAgainst Interpretation Essay Susan Sontag MkiWojtek WieczorekNessuna valutazione finora

- Giorgio Agamben Friendship 1 PDFDocumento6 pagineGiorgio Agamben Friendship 1 PDFcamilobeNessuna valutazione finora

- Eissler, K.R. (1959) - On Isolation. Psychoanal. St. Child, 14-29-60Documento20 pagineEissler, K.R. (1959) - On Isolation. Psychoanal. St. Child, 14-29-60Rams HamisNessuna valutazione finora

- The Jerry Saltz Abstract Manifesto, in Twenty Parts: Robert Ryman Agnes MartinDocumento2 pagineThe Jerry Saltz Abstract Manifesto, in Twenty Parts: Robert Ryman Agnes MartinAlfredo VillarNessuna valutazione finora

- Maggie Nelson Interview-LARB-Riding The BlindsDocumento7 pagineMaggie Nelson Interview-LARB-Riding The BlindsCaelulalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Adam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroDocumento12 pagineAdam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroedifyingNessuna valutazione finora

- Existentialism Is A HumanismDocumento4 pagineExistentialism Is A HumanismAlex MendezNessuna valutazione finora

- Braidotti The Posthuman-LibreDocumento4 pagineBraidotti The Posthuman-LibreAnaMateusNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ethic of Care For The Self As A Practice of FreedomDocumento21 pagineThe Ethic of Care For The Self As A Practice of Freedompapa0ursNessuna valutazione finora

- Maurice Bouvet (1911-1960) 三语介绍Documento33 pagineMaurice Bouvet (1911-1960) 三语介绍FengNessuna valutazione finora

- Dramaturging Personal Narratives: Who am I and Where is Here?Da EverandDramaturging Personal Narratives: Who am I and Where is Here?Nessuna valutazione finora

- Senses of Upheaval: Philosophical Snapshots of a DecadeDa EverandSenses of Upheaval: Philosophical Snapshots of a DecadeNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Equality Argument SuggestionsDocumento1 paginaGender Equality Argument SuggestionsdbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- 13 Vanderbilt Debate Tournament FinalsDocumento1 pagina13 Vanderbilt Debate Tournament FinalsdbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- College Tourney Schedule 2013Documento1 paginaCollege Tourney Schedule 2013dbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- Oklahoma Langel Wyde Aff UMKC Round2Documento3 pagineOklahoma Langel Wyde Aff UMKC Round2dbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- 00 Ndtreport Apr 09 1Documento21 pagine00 Ndtreport Apr 09 1dbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Vitae: and Culture (Appointed 1989)Documento31 pagineCurriculum Vitae: and Culture (Appointed 1989)dbhingstNessuna valutazione finora

- Windows SCADA Disturbance Capture: User's GuideDocumento23 pagineWindows SCADA Disturbance Capture: User's GuideANDREA LILIANA BAUTISTA ACEVEDONessuna valutazione finora

- Diploma Pendidikan Awal Kanak-Kanak: Diploma in Early Childhood EducationDocumento8 pagineDiploma Pendidikan Awal Kanak-Kanak: Diploma in Early Childhood Educationsiti aisyahNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEDocumento15 pagineChapter 4 INTRODUCTION TO PRESTRESSED CONCRETEyosef gemessaNessuna valutazione finora

- Trudy Scott Amino-AcidsDocumento35 pagineTrudy Scott Amino-AcidsPreeti100% (5)

- Simple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseDocumento2 pagineSimple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseFarris Ab RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- NCPDocumento3 pagineNCPchesca_paunganNessuna valutazione finora

- Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageDocumento11 pagineChildbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageWenny Indah Purnama Eka SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Equine PregnancyDocumento36 pagineEquine Pregnancydrdhirenvet100% (1)

- 2023-Tutorial 02Documento6 pagine2023-Tutorial 02chyhyhyNessuna valutazione finora

- WFRP - White Dwarf 99 - The Ritual (The Enemy Within)Documento10 pagineWFRP - White Dwarf 99 - The Ritual (The Enemy Within)Luife Lopez100% (2)

- Shielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestDocumento4 pagineShielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestFelix MilanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresDocumento40 pagineChapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresTeltel BillenaNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Export: 1) Establishing An OrganisationDocumento5 pagineHow To Export: 1) Establishing An Organisationarpit85Nessuna valutazione finora

- Computer Application in Chemical EngineeringDocumento4 pagineComputer Application in Chemical EngineeringRonel MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11Documento12 pagineMezbah Uddin Ahmed (173-017-054) Chapter 11riftNessuna valutazione finora

- A Terrifying ExperienceDocumento1 paginaA Terrifying ExperienceHamshavathini YohoratnamNessuna valutazione finora

- Quarter: FIRST Week: 2: Ballecer ST., Central Signal, Taguig CityDocumento2 pagineQuarter: FIRST Week: 2: Ballecer ST., Central Signal, Taguig CityIRIS JEAN BRIAGASNessuna valutazione finora

- List de VerbosDocumento2 pagineList de VerbosmarcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Liver Disease With PregnancyDocumento115 pagineLiver Disease With PregnancyAmro Ahmed Abdelrhman100% (3)

- Case AnalysisDocumento25 pagineCase AnalysisGerly LagutingNessuna valutazione finora

- A Photograph (Q and Poetic Devices)Documento2 pagineA Photograph (Q and Poetic Devices)Sanya SadanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ergatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoDocumento58 pagineErgatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoCristian David Urueña UribeNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Technical Analysis: - Online Live Interactive SessionDocumento4 pagineAdvanced Technical Analysis: - Online Live Interactive SessionmahendarNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilti Product Technical GuideDocumento16 pagineHilti Product Technical Guidegabox707Nessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic ManagementDocumento14 pagineStrategic ManagementvishakhaNessuna valutazione finora

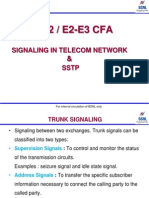

- Signalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDocumento39 pagineSignalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDilan TuderNessuna valutazione finora

- 206f8JD-Tech MahindraDocumento9 pagine206f8JD-Tech MahindraHarshit AggarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Aspects of The Language - Wintergirls Attached File 3Documento17 pagineAspects of The Language - Wintergirls Attached File 3api-207233303Nessuna valutazione finora