Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Cogre Thinking Definition of Term Pregnancy

Caricato da

Adan JuanDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Cogre Thinking Definition of Term Pregnancy

Caricato da

Adan JuanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Current Commentary

Rethinking the Definition of Term Pregnancy

Alan R. Fleischman,

MD,

Motoko Oinuma,

BA,

and Steven L. Clark,

MD

Term birth (37 41 weeks of gestation) has previously been considered a homogeneous group to which risks associated with preterm (less than 37 weeks of gestation) and postterm births (42 weeks of gestation and beyond) are compared. An examination of the history behind the definition of term birth reveals that it was determined somewhat arbitrarily. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that significant differences exist in the outcomes of infants delivered within this 5-week interval. We focus attention on a subcategory of term births called early term, from 37 0/7 to 38 6/7 weeks of gestation, because there are increasing data that these births have increased mortality and neonatal morbidity as compared with neonates born later at term. The designation term carries with it significant clinical implications with respect to the management of pregnancy complications as well as the timing of both elective and indicated delivery. Management of pregnancies should clearly be guided by data derived from gestational agespecific studies. We suggest adoption of this new subcategory of term births (early term births), and call on epidemiologists, clinicians, and researchers to collect data specific to the varying intervals of term birth to provide new insights and strategies for improving birth outcomes.

(Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1369)

before this interval (less than 37 completed weeks of pregnancy) are classified as preterm, whereas those delivered beyond this interval (42 weeks and beyond) are designated postterm.1,2 Although the potential hazards of both preterm birth and postterm pregnancy have been long recognized, little attention has been given to the differential morbidity experienced by neonates born within the broad category of term gestation. Term birth has previously been considered a homogeneous group to which risks associated with preterm and postterm births are compared, but there is a growing body of data that suggests that significant differences exist in the outcomes of infants delivered within this 5-week interval. Because the designation term carries with it significant clinical implications with respect to the management of pregnancy complications as well as the timing of both elective and indicated delivery, a reevaluation of the concept of term pregnancy in light of current data is in order. We propose new definitions as described in Table 1.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Over 100 years ago, J. Whitworth Williams wrote in the first edition of what was to become the classic text, Williams Obstetrics, We possess no reliable means of estimating the exact date (of confinement) but are obliged to content ourselves with the method proposed by Naegele, which is based upon the belief that labor occurs two hundred eighty days from the beginning of the last menstrual period.3 It was not until 50 years later, in 1948, that the World Health Assembly proposed an international definition of a premature infant as one with a birth weight of less than 2,500 g, a gestational age of less than 38 completed weeks, or both.4 One year later, in 1949, the Standard Certificate of Live Birth developed by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was revised to include reporting of the length of pregnancy in weeks and was revised in 1956 to specify the reporting of completed weeks of gestation.5 A 1961 report by the

erm pregnancy has traditionally been defined as one in which 260 294 days have elapsed since the first day of the last menstrual period. Neonates born

See related editorial on page 4.

From the National Office, March of Dimes, White Plains, New York; the Hospital Corporation of America, Nashville, Tennessee; and the Departments of Pediatrics and Epidemiology and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York. Corresponding author: Alan R. Fleischman, MD, Senior Vice President and Medical Director, March of Dimes, 1275 Mamaroneck Avenue, White Plains, NY 10605; e-mail: afleischman@marchofdimes.com. Financial Disclosure The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. 2010 by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISSN: 0029-7844/10

136

VOL. 116, NO. 1, JULY 2010

OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

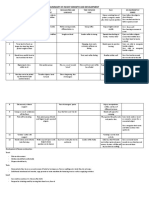

Table 1. Definition and Description of Gestational Age

Description

Preterm Late preterm Term Early term Full term Postterm

Gestational Age (wk)

Less than 37 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 37 0/7 to 41 6/7 37 0/7 to 38 6/7 39 0/7 to 41 6/7 42 or greater

Expert Committee on Maternal and Child Health of the World Health Organization recognized a distinction between premature and low birth weight infants.4 Nine years later, in 1970, a group of obstetricians and pediatricians at the Second European Congress of Perinatal Medicine outlined a classification that placed the boundary between preterm and term at 37 weeks of gestation.6 This appears to be the basis for the current definition of prematurity that is widely accepted by professional organizations.1,2,5 The precise origins of the 42-week definition of postterm pregnancy are somewhat more obscure but appear to be related to a report from Sweden in 1956 of a dramatic increase in perinatal mortality seen beyond this time during the years 19431952.7

TERM GESTATION

Thus, it appears that the definition of term gestation was determined somewhat arbitrarily with reference primarily to differentiating this period from the complications associated with earlier and later gestational periods. However, gestational age is a biologic continuum and new data reveal important insights into the outcomes of babies born during this 5-week period called term.8 New epidemiologic studies reveal that the most common length of gestation in spontaneous singleton live births has changed significantly in the decade before 2002. During this period, the most common length of gestation decreased from 40 weeks to 39 weeks with deliveries at 40 weeks or more decreasing significantly, whereas those at 34 39 weeks increased.9 In addition, there are increasing data to support that early term births, neonates born between 37 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks of gestation, have increased mortality and neonatal morbidity as compared with neonates born later at term.10,11 An analysis of U.S. singleton live births at term between 1995 and 2001 found that the mortality rate decreased with increasing gestational age from 0.66 per 1,000 live births at 37 weeks to 0.33 per 1,000 live births at 39 weeks and remained stable from 39 to 40 weeks.12 Despite a low absolute risk of infant death at term, the

risks were more than 50% higher at 37 weeks than at 40 weeks, and although the main analysis was restricted to non-Hispanic whites, there were similar patterns among non-Hispanic African Americans. An abstract analyzing the 2001 National Center for Health Statistics birth cohort of singleton gestations also found increased neonatal and infant mortality rates for early term births at 37 and 38 weeks compared with 39 weeks of gestation.11 The rates for neonatal infection and later sudden infant death syndrome also decrease with increasing gestational age. Previous studies as early as the mid-1990s have shown that neonatal respiratory morbidity was associated with term elective cesarean delivery (cesarean delivery before labor) before 39 weeks of gestation13 with one large study showing decreasing risk with increasing gestational age.14 There is more current evidence that elective early term births are associated with increased short-term respiratory morbidities and newborn intensive care admissions as compared with full-term neonates.1517 Two recent studies, one examining elective repeat cesarean deliveries at 37 and 38 weeks and the other reporting on elective cesarean delivery at term before 39 weeks, were associated with a higher risk of neonatal complications, including respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit compared with deliveries at 39 weeks.17,18 Another study found that elective delivery before 39 weeks of gestation (including elective inductions, elective repeat cesarean deliveries, and elective primary cesarean deliveries) is associated with significant neonatal morbidity with 17.8% of neonates delivered electively at 37 to 38 weeks and 8% of those delivered electively at 38 to 39 weeks requiring admission to a newborn special care unit for an average of 4.5 days compared with 4.6% of neonates delivered at 39 weeks or beyond.15 Neonatal morbidities experienced by these early-term neonates lead to increased admission to neonatal intensive care units, which results in increased medical costs. These cost implications need to be further documented and considered, especially in light of preventable early term births resulting from elective delivery. In summary, there appears to be a continuous relationship between gestational age and neonatal morbidities with a nadir at 39 weeks of gestation.19 Rather than reaching a critical threshold, the rate of neonatal morbidity decreases gradually as gestational age increases from 34 weeks and plateaus at 39 40 weeks. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that no elective induction or cesarean delivery be performed before 39 weeks

VOL. 116, NO. 1, JULY 2010

Fleischman et al

Rethinking the Definition of Term Pregnancy

137

without clinical indication or evidence of fetal lung maturity20,21 and points out that even a mature fetal lung test result before 39 weeks of gestation, in the absence of appropriate clinical circumstances, is not an indication for delivery.21 In addition, the National Quality Forum and the Joint Commission recently endorsed as one of their standardized perinatal care measurements reporting of all singletons delivered at 37 or more completed weeks of gestation that are electively delivered before 39 completed weeks of gestation.22,23 Although there are clearly instances when delivery before 39 weeks of gestation is medically indicated, our concern is for nonmedical factors leading to elective delivery before 39 weeks such as maternal request, physician schedules, or a combination of social factors related to convenience. Moreover, early induction has a greater chance of resulting in a cesarean delivery, particularly with an unfavorable cervix.24 A survey of women who recently gave birth found that over half believed that full term was reached at 3738 weeks of gestation and that most believed it is safe to deliver before 39 weeks of gestation when there are no other medical complications requiring early delivery.25 Thus, in addition to quality improvement programs and physician education to address this issue from the perspective of the provider, it is also important to communicate to pregnant women and their families the possible negative consequences of early elective delivery.

suggest that neonates born at term form a heterogeneous group and that those born earlier in the term period and those born later need to be considered as separate subgroups. Additional research is needed to elucidate associated long-term adverse outcomes for those babies born early term between 37 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks as compared with babies born later at 39 41 weeks or full term. There is also a need to elucidate the cost implications of the elective delivery of these early term neonates. Moreover, clearer terminology separating early term from full-term births would be useful to educate women when discussing implications of the best timing for delivery. We suggest the universal adoption of the use of early term to describe the subcategory of term births born between 37 0/7 and 38 6/7 weeks of gestation. Management of pregnancies in each of these categories should clearly be guided by data derived from gestational-age specific studies. We call on epidemiologists, clinicians, and researchers to collect data distinguishing early term births and their outcomes from babies born later at full term to provide new insights and strategies for improving birth outcomes. REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Rev. 10, vols 1 and 2, ICD-10. Geneva: WHO; 1992. 2. American Academy of Pediatrics/American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Appendix D: standard terminology for reporting of reproductive health statistics in the United States. In: Guidelines for perinatal care. 6th ed. Elk Grove (IL): AAP/ACOG; 2007. p. 389 404. 3. Williams JW. Williams obstetrics. 1st ed. New York (NY): D. Appleton and Company; 1903. 4. Drillien CM. The low-birth weight infant. In: Cockburn F, Drillien CM, editors. Neonatal medicine. Osney Mead (Australia): Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1974. p. 51 61. 5. Preterm birth. In: From data to action: CDCs public health surveillance for women, infants and children. Atlanta (GA): The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. 6. Working party to discuss nomenclature based on gestational age and birthweight. Arch Dis Child 1970;45:730. 7. Lindell A. Prolonged pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1956;35:136 63. 8. Bailit JL, Gregory KD, Reddy UM, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Hibbard JU, Ramirez MM, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes by labor onset type and gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:245.e112. 9. Davidoff MJ, Dias T, Damus K, Russell R, Bettegowda VR, Dolan S, et al. Changes in the gestational age distribution among US singleton births: impact on rates of late preterm birth, 1992 to 2002. Semin Perinatol 2006;30:8 15. 10. Engle WA, Kominiarek MA. Late preterm infants, early term infants, and timing of elective deliveries. Clin Perinatol 2008; 35:325 41, vi.

RETHINKING THE DEFINITION OF TERM PREGNANCY

In recent years, there has been general agreement about the use of a new expression, late preterm, to define neonates born between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation.26,27 This subcategory of preterm births was instituted based on new epidemiologic and outcome data and has been useful in highlighting a subgroup of preterm births that contributes significantly to the growing rate of prematurity in the United States and has been shown to have a higher risk of neonatal complications than previously appreciated. We believe it makes similar sense to create a new subcategory of term births called early term, from 37 0/7 to 38 6/7 weeks, to focus on an important period in gestation that also has been shown to have a higher risk of neonatal complications and would benefit from more careful assessment and concern.

CONCLUSIONS

Term birth has previously been considered a homogeneous group to which risks associated with preterm and postterm births are compared. However, the data

138

Fleischman et al

Rethinking the Definition of Term Pregnancy

OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

11. Reddy UM, Ko CW, Willinger M. Early term births (3738 weeks) are associated with increased mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:S202. 12. Zhang X, Kramer MS. Variations in mortality and morbidity by gestational age among infants born at term. J Pediatr 2009;154:358 62, 362.e1. 13. Hansen AK, Wisborg K, Uldbjerg N, Henriksen TB. Elective caesarean section and respiratory morbidity in the term and near-term neonate. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86: 389 94. 14. Morrison JJ, Rennie JM, Milton PJ. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102: 101 6. 15. Clark SL, Miller DD, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Frye DK, Meyers JA. Neonatal and maternal outcomes associated with elective term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:156.e1 4. 16. Oshiro BT, Henry E, Wilson J, Branch DW, Varner MW. Decreasing elective deliveries before 39 weeks of gestation in an integrated health care system. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113: 804 11. 17. Tita AT, Landon MB, Spong CY, Lai Y, Leveno KJ, Varner MW, et al. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:11120. 18. Wilmink FA, Hukkelhoven CW, Lunshof S, Mol BW, van der Post JA, Papatsonis DN. Neonatal outcome following elective cesarean section beyond 37 weeks of gestation: a 7-year retrospective analysis of a national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:250.e1 8. 19. Melamed N, Klinger G, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Herscovici T, Linder N, Hod M, et al. Short-term neonatal outcome in

20.

21.

22.

23.

24. 25.

26.

27.

low-risk, spontaneous, singleton, late preterm deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:253 60. Cesarean delivery on maternal request. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 394. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1501 4. Induction of labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:386 97. The National Quality Forum. NQF 0469. Elective delivery prior to 39 completed weeks gestation. Endorsed October 28, 2008. Available at: http://qualityforum.org/Measures_List.aspx. Retrieved January 20, 2009. The Joint Commission. Specifications Manual for Joint Commission National Quality Core Measures (2010A1). Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/ PerformanceMeasurement/PerinatalCareCoreMeasure Set.htm. Retrieved January 20, 2009. Glantz JC. Term labor induction compared with expectant management. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:70 6. Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Bhattacharya A, Groat TD, Stahl PJ. Womens perceptions regarding the safety of births at various gestational ages. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114: 1254 8. Engle WA. A recommendation for the definition of late preterm (near-term) and the birth weight-gestational age classification system. Semin Perinatol 2006;30:27. Raju TN, Higgins RD, Stark AR, Leveno KJ. Optimizing care and outcome for late-preterm (near-term) infants: a summary of the workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatrics 2006;118:120714.

VOL. 116, NO. 1, JULY 2010

Fleischman et al

Rethinking the Definition of Term Pregnancy

139

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento3 pagineAnnotated Bibliographyapi-286145913Nessuna valutazione finora

- Competency Statement IDocumento2 pagineCompetency Statement Ihllacinski002Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Postpartum - PedsDocumento3 pagineCase Study Postpartum - PedsRoze Petal0% (1)

- The Hidden Feelings of Motherhood: Coping With Stress, Depression, and BurnoutDocumento3 pagineThe Hidden Feelings of Motherhood: Coping With Stress, Depression, and BurnoutAdalene SalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Normal University College of Education Department of Professional EducationDocumento7 paginePhilippine Normal University College of Education Department of Professional Educationapi-26570979Nessuna valutazione finora

- Implementation of Child Custody Laws in IndiaDocumento11 pagineImplementation of Child Custody Laws in Indiaakash tiwariNessuna valutazione finora

- District Manager Multi Unit in Greater Grand Rapids Mi Resume Amber HortonDocumento2 pagineDistrict Manager Multi Unit in Greater Grand Rapids Mi Resume Amber HortonAmber HortonNessuna valutazione finora

- Stages of Parenthood: Galinsky's Six Parental StagesDocumento2 pagineStages of Parenthood: Galinsky's Six Parental StagesRommel Villaroman EstevesNessuna valutazione finora

- ReflectionDocumento4 pagineReflectionAurea Jasmine Dacuycuy100% (1)

- Lina Widi Astuti 1308111 Nonfull-Ilovepdf-Compressed-DikonversiDocumento36 pagineLina Widi Astuti 1308111 Nonfull-Ilovepdf-Compressed-DikonversiViott WNNessuna valutazione finora

- Sudden Infant Death SyndromeDocumento2 pagineSudden Infant Death SyndromerangaNessuna valutazione finora

- CMCA Lec 1Documento10 pagineCMCA Lec 1DARLENE ROSE BONGCAWILNessuna valutazione finora

- Worksheets Family PDFDocumento2 pagineWorksheets Family PDFPatricia Garcia VNessuna valutazione finora

- MGP Brochure 1Documento2 pagineMGP Brochure 1api-331438593Nessuna valutazione finora

- Child AbuseDocumento5 pagineChild AbuseJohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychosexual and Psychosocial DevelopmentDocumento22 paginePsychosexual and Psychosocial DevelopmentRizza Manabat PacheoNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of RelatDocumento1 paginaReview of RelatAlzamin DimananalNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Abuse and NeglectDocumento11 pagineChild Abuse and NeglectAmit RawlaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 293 871 3 PBDocumento7 pagine293 871 3 PBDiana PertiwiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment Diagnosis Rationale Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocumento2 pagineAssessment Diagnosis Rationale Planning Intervention Rationale Evaluationbambem aevanNessuna valutazione finora

- Home VisitsDocumento47 pagineHome VisitsHaironisaMalaoMacagaan80% (5)

- Biblioteca Della Ricerca: Cultura Straniera 66Documento7 pagineBiblioteca Della Ricerca: Cultura Straniera 66santiagopalermoNessuna valutazione finora

- Edu119 Final Exam Sheila VazquezDocumento5 pagineEdu119 Final Exam Sheila Vazquezapi-231342304Nessuna valutazione finora

- Genie, The Feral Child: Zamboanga City State Polytechnic CollegeDocumento2 pagineGenie, The Feral Child: Zamboanga City State Polytechnic CollegeAiko SansonNessuna valutazione finora

- Risky Behaviors of Adolescence - Gender and SocietyDocumento23 pagineRisky Behaviors of Adolescence - Gender and SocietyROCELLE S. CAPARRONessuna valutazione finora

- Gotiangco, Christian Laine B. Beed-1CDocumento1 paginaGotiangco, Christian Laine B. Beed-1CLaineNessuna valutazione finora

- TOWARDS A BETTER START Updated Summary Report FinalDocumento16 pagineTOWARDS A BETTER START Updated Summary Report FinalAnonymous BQw2frLKcNessuna valutazione finora

- NTT Exam-2013Documento23 pagineNTT Exam-2013harishNessuna valutazione finora

- Daycare CertificateDocumento14 pagineDaycare CertificateWalter JensenNessuna valutazione finora

- Resilience in ChildrenDocumento27 pagineResilience in Childrenapi-383927705Nessuna valutazione finora