Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery: Module Menu

Caricato da

Khairul MustafaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery: Module Menu

Caricato da

Khairul MustafaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

VICNISS Hospital Acquired Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre 10 Wreckyn Street North Melbourne VIC 3051 Tel: 03 9342

2605 Fax: 03 9342 2633 email: vicniss@mh.org.au web: www.vicniss.org.au

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery

Module 4 VICNISS online self guided surveillance education (www.vicniss.org.au/HCW/EducationModules/Index.aspx)

Module Menu

Overview Objectives Introduction Measures to Reduce Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) Drugs of Choice Timing of Antibiotic Administration Dosing & Duration of Antibiotic Prophylaxis Anaphylaxis to Beta-Lactam Antibiotics Recommended Prophylaxis for Selected Operations Further Information ReferencesReferences Test your Knowledge Exercise 1

Overview This module gives an overview of the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery. Objectives After you have completed this module, you should be able to: 1. Explain how surgical site infections can be prevented; 2. Understand the recommended doses, duration and timing of antibiotics used for surgical prophylaxis; and 3. Understand the recommended prophylaxis regimens for selected operations. Introduction Among surgical patients, surgical site infections (SSIs) are the most common nosocomial infection, accounting for 38 percent of nosocomial infections. It is estimated that SSIs develop in 2 to 5 percent of patients who undergo surgery. The costs of SSIs are substantial, and include patient costs (morbidity, mortality, lost income), and costs to the hospital system (repeat surgery, increased length of stay, long antibiotic courses). The goal of antimicrobial prophylaxis is to eradicate or retard the growth of endogenous microorganisms. The efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in clean and clean-contaminated surgery has been clearly established. Most clean surgeries do not require antimicrobial prophylaxis unless there is a high risk of infection or the consequences of a SSI are disastrous (eg. CABG, insertion of a prosthesis, or laminectomy).

Reviewed 2006

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery

Module 4 VICNISS online self guided surveillance education

Measures to Reduce Surgical Site Infections Control measures to reduce SSI rates include: Maximising the general health of the patient (optimising nutrition, weight control, blood glucose control, and smoking cessation); Meticulous operative techniques (effective hemostasis, removal of devitalised tissues, obliteration of dead space, use of closed suction drains, and wound closure without tension); and Timely administration of preoperative antibiotics. Surgical Care Improvement Project: ww.cfmc.org/hospital/hospital_scip.htm Recent data suggests that attention to intraoperative temperature control, and supplemental oxygen administration along with aggressive fluid resuscitation may reduce infection rates. The use of barrier devices (masks, caps, gowns, drapes, and shoe covers) to prevent SSIs is not supported by rigorously controlled and valid clinical studies. The primary role for these barrier devices is to protect operating room personnel from exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. A number of practices (such as preoperative showering of the patient, and barrier devices for staff) have been tried over the years in an effort to both decontaminate patients and to reduce contact between the operative field and flora from hospital personnel. However, most SSIs are caused by microorganisms that already colonise the patient, and therefore the major source of SSIs is not the staff. In addition, modern methods of antisepsis can reduce, but not eliminate, the skin-associated bacteria of the surgical patient; approximately 20 percent of the bacteria are located in hair follicles and sebaceous glands, which are not reached with preoperative antiseptic agents. Drugs of Choice First generation cephalosporins (e.g. cephazolin) are the drugs of choice for prophylaxis for most clean procedures because of their low incidence of allergy and side effects, antibacterial spectrum, long half-life, and low cost. For patients with known MRSA colonisation, vancomycin should be considered an appropriate agent for prophylaxis. Timing of Antibiotic Administration The timing of intravenous antibiotic administration is important. The relative risk of wound infection is related to the time of antibiotic administration with the optimal time being immediately before the surgical incision. When antibiotics are given more than 2 hours before, the relative risk of infection is 6.7 times higher and when given after the incision is made, the relative risk is 2.4. For these reasons, intravenous antibiotics should be given as close to the time of induction of anaesthesia as possible, but no more than 2 hours before the skin incision is made. Infusion of the antibiotic should begin within 60 minutes before incision, however, for certain agents that require a longer infusion time (such as vancomycin), the infusion should begin within 120 minutes before the incision.

VICNISS Hospital Acquired Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre Page 2 of 5

Reviewed 2006

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery

Module 4 VICNISS online self guided surveillance education

Dosing & Duration of Antibiotic Prophylaxis In general, a single dose of a parenteral drug is sufficient. Re-dosing may be required in prolonged procedures, or where there has been significant delay in starting the operation. In these cases, administration should be repeated at 1-2 half-lives after the first dose. For example, cephazolin can be re-dosed after 4 hours. The practice of continuing antibiotic prophylaxis while surgical drains are in-situ is of unproven benefit. Most studies comparing single-dose prophylaxis with multiple-dose prophylaxis have not shown benefit of additional doses. There are however some examples of surgery where continuing antibiotic prophylaxis is associated with improved outcomes, e.g. reduction and internal fixation of traumatic compound fractures. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be provided in an adequate dose based on patient body weight. For example, cephazolin should be dosed at 2g for patients who weigh in excess of 80 kg. Anaphylaxis to Beta-Lactam Antibiotics In the setting of a patient with a history of immediate anaphylaxis to beta-lactam antibiotics (usually penicillin or its derivatives) the recommended alternatives are vancomycin or clindamycin for Gram-positive cover. Examples of other non-beta-lactam antibiotics are; rifampicin, gentamicin, aztreonam and ciprofloxacin. Recommended Prophylaxis for Selected Operations: Different hospitals may have their own prophylaxis protocols, and antibiotic restriction policies. The recommendations below are merely intended as a guide to good practice. These protocols are largely based on Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic (version 12) with some modifications available online: www.tg.com.au/index.php?sectionid=41 and www.etg.hcn.net.au ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR ABDOMINAL SURGERY (COLORECTAL, APPENDICECTOMY, UPPER GIT OR BILIARY, INCLUDING LAPAROSCOPIC): Prophylaxis is appropriate for all patients undergoing abdominal surgery, even low-risk procedures. The antimicrobial must be active against Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes. A single dose of antibiotic is sufficient, however if the procedure is prolonged beyond 3 hours a second dose of cephazolin or timentin should be given. Metronidazole may be re-dosed after 4 hours. Metronidazole 500mg IV ending infusion prior to induction. plus Cephazolin 1g IV at the time of induction. or Timentin 3.1g IV as a single agent. Metronidazole may be omitted in upper GIT surgery without obstruction or malignancy, and in low-risk biliary surgery.

VICNISS Hospital Acquired Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre Page 3 of 5

Reviewed 2006

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery

Module 4 VICNISS online self guided surveillance education

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR CARDIAC SURGERY: Most authorities recommend: Cephazolin 1g IV at the time of induction. However, if there is a high endemic rate of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and the duration of hospitalisation pre-operatively is long, an alternative is: Vancomycin 1g IV over at least 1 hour, ending the infusion at the time of induction.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR CAESAREAN SECTION: In general, it is recommended that antibiotics be administered after cord clamping. Recommend: Cephazolin 1g IV, immediately after clamping the cord.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR HERNIA REPAIR: Prophylaxis is not indicated for hernia repair without prosthetic material. In surgery that includes the implantation of mesh the following is recommended: Metronidazole 500mg IV ending infusion prior to induction. plus Cephazolin 1 g IV at the time of induction.

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS FOR ORTHOPAEDIC SURGERY: Prophylaxis is required for total joint replacements, and should target the likely pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci). The following is recommended: Cephazolin 1 g IV at induction. or Di/flucloxacillin 2 g IV at induction. If a proximal tourniquet is used, the antimicrobial should be completely infused before inflation.

VICNISS Hospital Acquired Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre

Page 4 of 5

Reviewed 2006

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery

Module 4 VICNISS online self guided surveillance education

Test your Knowledge - Exercise 1 (See Exercises) Further Information If you have any questions about antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery that are not answered in this module, please call the VICNISS Coordinating centre on 9342 2605. VICNISS Website Home Page: www.vicniss.org.au Information on appropriate prescribing in the Victorian Healthcare setting: Therapeutic Guidelines Antibiotic Version 12, 2003: www.tg.com.au/index.php?sectionid=41 and www.etg.hcn.net.au US National Guidelines Clearinghouse: www.guideline.gov Surgical Care Improvement Project: www.cfmc.org/hospital/hospital_scip.htm Advisory statement on antibiotic prophylaxis for surgery from the National Surgical infection Prevention Project (US): www.journals.uchicago.edu/CID/journal/issues/v38n12/33257/33257.html References E. Patchen Dellinger, Peter A. Gross, Trisha L. Barrett, Peter J. Krause, William J. Martone, John E. McGowan, Jr., Richard L. Sweet, and Richard P. Wenzel. Quality Standards for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgical Procedures. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1994;18:422-7 Dale W. Bratzler1 and Peter M. Houck,2 for the Surgical Infection Prevention Guidelines Writers Workgroup Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Surgery: An Advisory Statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project Clinical Infectious Diseases 2004;38:1706-1715 Darouiche RO. Antimicrobial approaches for preventing infections associated with surgical implants. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003; 36(10):1284-9

VICNISS Hospital Acquired Infection Surveillance Coordinating Centre

Page 5 of 5

Reviewed 2006

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Policies On Rational Antimicrobial Use Based On The Hospital Antibiogram and Survailance of AmrDocumento10 paginePolicies On Rational Antimicrobial Use Based On The Hospital Antibiogram and Survailance of AmrAnonymous jQM5jMK0100% (3)

- The Macrobiotic Approach To CancerDocumento181 pagineThe Macrobiotic Approach To CancerFady Nassar100% (12)

- Antibiotic in Obstetric and GynecologyDocumento36 pagineAntibiotic in Obstetric and GynecologyDrAbdi YusufNessuna valutazione finora

- Perioperative Infection Control in Cardiothoracic SurgeryDocumento41 paginePerioperative Infection Control in Cardiothoracic SurgeryVenkata Raja sekhara Rao KetanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Barksy - The Paradox of Health PDFDocumento5 pagineBarksy - The Paradox of Health PDFdani_g_1987Nessuna valutazione finora

- Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis StatPearls NCBI BookshelfDocumento1 paginaPreoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis StatPearls NCBI BookshelfJEAN BAILEY RAMOS ROXASNessuna valutazione finora

- Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento6 paginePreoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAshen DissanayakaNessuna valutazione finora

- Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento7 paginePreoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfMikaela l100% (1)

- Adult ENT Antibiotic Surgical Prophylaxis Guidelines: Full Title of Guideline: AuthorDocumento7 pagineAdult ENT Antibiotic Surgical Prophylaxis Guidelines: Full Title of Guideline: Authorai naNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in SurgeryDocumento10 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis in SurgeryHaSan Z. MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotics in ENT Surgery: Magdy M. Amin RIADDocumento57 pagineAntibiotics in ENT Surgery: Magdy M. Amin RIAD1974sathyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Antibiotic ProphylaxisDocumento3 pagineSurgical Antibiotic Prophylaxisbellahunter92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic 4 SurgicalDocumento3 pagineAntibiotic 4 SurgicalNanaDinaWahyuniNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotics in NeurosurgeryDocumento12 pagineAntibiotics in Neurosurgerylouglee9174100% (1)

- CrosstownGeneralSurgeryGuidelineFinal Nov 2007Documento8 pagineCrosstownGeneralSurgeryGuidelineFinal Nov 2007Sri Nurliana BasryNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Duration Position Statement October 2021 v1Documento3 pagineSurgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Duration Position Statement October 2021 v1debby twonabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Isid Guide Preparing The Patient For Surgery-1Documento16 pagineIsid Guide Preparing The Patient For Surgery-1Prunaru BogdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobial ProphylaxisDocumento2 pagineAntimicrobial ProphylaxisbournvilleeaterNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Neurosurgery Adult and Paediatric PatientsDocumento6 pagineSurgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Neurosurgery Adult and Paediatric PatientsPraveen PadalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Antimicrobial Prophylaxis: Version 3 - Updated May 2019Documento33 pagineSurgical Antimicrobial Prophylaxis: Version 3 - Updated May 2019NailahRahmahNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic PolicyDocumento38 pagineAntibiotic Policysapphiresalem9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis PDFDocumento3 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis PDFPadmanabha GowdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotika Profilaksis Pada Operasi Orthopaedi RevisiDocumento30 pagineAntibiotika Profilaksis Pada Operasi Orthopaedi RevisiAnis ChaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotc ProphylaxisDocumento22 pagineAntibiotc Prophylaxisgitama9904Nessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotics in Abdominal SurgeryDocumento52 pagineAntibiotics in Abdominal SurgerySangamesh KNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in SurgeryDocumento23 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis in SurgeryRakhmad AdityaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis and Culligan GYN SSI Reduction 42Documento5 pagineLewis and Culligan GYN SSI Reduction 42Ahmed Mohamed SalehNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis - TinoDocumento24 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis - Tinoazka novriandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobials in Gynaecological PracticeDocumento5 pagineAntimicrobials in Gynaecological PracticeannisanabilaasNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotics in Surgery: July 2010Documento31 pagineAntibiotics in Surgery: July 2010louglee9174Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cephalosporins in Surgical Prophylaxis: ReviewDocumento4 pagineCephalosporins in Surgical Prophylaxis: ReviewGemara HanumNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Selection GuideDocumento37 pagineAntibiotic Selection GuideAbanoub Nabil100% (1)

- Clinic-Pharmacologic Approaches To Antimicrobial Therapy in Surgical InfectionsDocumento27 pagineClinic-Pharmacologic Approaches To Antimicrobial Therapy in Surgical InfectionsMuhammad NaveedNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Prophylactic AntibioticsDocumento6 pagineUse of Prophylactic AntibioticsDavid ArévaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis-An EssayDocumento12 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis-An EssayGokul RamakrishnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemo ProphylaxisDocumento13 pagineChemo ProphylaxisSaket DaokarNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotics-Generation OperationDocumento5 pagineAntibiotics-Generation OperationZamzami Ahmad FahmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Guideline Wound InfectionDocumento5 pagineGuideline Wound Infectioncut fatiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Profilaxis AntiibioticaDocumento6 pagineProfilaxis AntiibioticaAndrés RezucNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Stewardship in OrthopedicsDocumento17 pagineAntibiotic Stewardship in Orthopedicsjomari dvNessuna valutazione finora

- ATB ProfilaxisDocumento10 pagineATB Profilaxiscristopher_ahcNessuna valutazione finora

- Pocket Guide, January 1, 2014 Version Urologic Surgery Antimicrobial Prophyl A XisDocumento3 paginePocket Guide, January 1, 2014 Version Urologic Surgery Antimicrobial Prophyl A XisPraveen RavishankaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Single-Dose Antibiotic Prophylaxis Versus Conventional Antibiotic Therapy in Surgery A Randomized Controlled Trial in A Public Teaching HospitalDocumento5 pagineEffect of Single-Dose Antibiotic Prophylaxis Versus Conventional Antibiotic Therapy in Surgery A Randomized Controlled Trial in A Public Teaching HospitalكنNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Neutropenia 4567Documento6 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Febrile Neutropenia 4567Hisham ElhadidiNessuna valutazione finora

- Trauma Laparotomy AntibioticsDocumento2 pagineTrauma Laparotomy AntibioticsYosep SembiringNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis - Is It Necessary in Clean General Surgery?Documento3 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis - Is It Necessary in Clean General Surgery?Jade Phoebe AjeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Laskin The Use of Prophylactic AntibioticsDocumento6 pagineLaskin The Use of Prophylactic Antibioticsapi-265532519Nessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobial StewardshipDocumento7 pagineAntimicrobial StewardshipMehwish MughalNessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobialstewardship Approachesinthe Intensivecareunit: Sarah B. Doernberg,, Henry F. ChambersDocumento22 pagineAntimicrobialstewardship Approachesinthe Intensivecareunit: Sarah B. Doernberg,, Henry F. ChambersecaicedoNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic SsiDocumento6 pagineAntibiotic Ssim8wyb2f6ngNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Plan Template - CareBundlesDocumento9 pagineTeaching Plan Template - CareBundlesCris GalendezNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Site Infection (SSI)Documento3 pagineSurgical Site Infection (SSI)Sahrul RiadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Prophylaxis and SSIsDocumento37 pagineSurgical Prophylaxis and SSIsTop Vids100% (1)

- Ajhp2312 Antibiotic ProphylaxisDocumento2 pagineAjhp2312 Antibiotic Prophylaxisarvi awaludinNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Stewardship in Critical Care: Ian Johnson MBCHB Frca and Victoria Banks Mbbs BSC Frca Fficm EdicDocumento6 pagineAntibiotic Stewardship in Critical Care: Ian Johnson MBCHB Frca and Victoria Banks Mbbs BSC Frca Fficm EdicRavi KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Rational Use of AntibioticsDocumento27 pagineRational Use of AntibioticsTesfaye MegersaNessuna valutazione finora

- Major RecommendationsDocumento6 pagineMajor RecommendationsAhmed MostafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving Compliance With Prophylactic Antibiotic Administration GuidelinesDocumento8 pagineImproving Compliance With Prophylactic Antibiotic Administration Guidelinesanshum guptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical PropgylaxisDocumento19 pagineSurgical Propgylaxisallymyly88Nessuna valutazione finora

- DCGC Antibiotic Surgical Prophylaxi ProtocolDocumento22 pagineDCGC Antibiotic Surgical Prophylaxi ProtocolStacey WoodsNessuna valutazione finora

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis: Niña Patricia V. Orbe Harold S. Talaue Minor Surgery L-Nu FQDMF College of MedicineDocumento17 pagineAntibiotic Prophylaxis: Niña Patricia V. Orbe Harold S. Talaue Minor Surgery L-Nu FQDMF College of MedicineNdor Baribolo100% (1)

- 5 PBDocumento10 pagine5 PBKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- National Descriptors Texture Modification AdultsDocumento21 pagineNational Descriptors Texture Modification AdultsKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- 07-3 Biopiracy Imitations Not InnovationsDocumento76 pagine07-3 Biopiracy Imitations Not InnovationsKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Travel Itinerary: Booking DetailsDocumento5 pagineTravel Itinerary: Booking DetailsKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Family+MedicineDocumento23 pagine2 Family+MedicineKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1principlesof FMDocumento26 pagine1principlesof FMKhairul MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Plan: University of Florida College of DentistryDocumento15 pagineStrategic Plan: University of Florida College of DentistrySatya AsatyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vision 2015: Medical Council of IndiaDocumento60 pagineVision 2015: Medical Council of IndiaAli Hyder SyedNessuna valutazione finora

- Indi Case StudyDocumento17 pagineIndi Case StudyKenTorredesNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter - 1: Eliott and Merrill (1951) Define Family As: "Family Is The Biological SocialDocumento32 pagineChapter - 1: Eliott and Merrill (1951) Define Family As: "Family Is The Biological SocialANANYANessuna valutazione finora

- HEALTH 8 3rd 4thDocumento5 pagineHEALTH 8 3rd 4thBrian CorpuzNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Health Psychology 6th by StraubDocumento14 pagineTest Bank For Health Psychology 6th by Straubmichelletorresrgqjonxwiz100% (29)

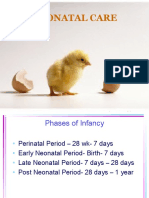

- Neonatal Care: Dr. Bhuwan Sharma Asst. ProfessorDocumento28 pagineNeonatal Care: Dr. Bhuwan Sharma Asst. Professorrevathidadam55555Nessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Copassion Fatigue PosterDocumento1 paginaImpact of Copassion Fatigue Posterapi-384505435Nessuna valutazione finora

- Road Traffic Injury Prevention ManualDocumento126 pagineRoad Traffic Injury Prevention ManualthimjoplakuNessuna valutazione finora

- Noah Irvine's Letter To Prime Minister Justin TrudeauDocumento2 pagineNoah Irvine's Letter To Prime Minister Justin TrudeauHuffPost CanadaNessuna valutazione finora

- CHN ReviewerDocumento410 pagineCHN ReviewerklynemaxNessuna valutazione finora

- CHN Assignment (Community Health Nursing)Documento21 pagineCHN Assignment (Community Health Nursing)binjuNessuna valutazione finora

- Roadmap For 2023 - 2030Documento18 pagineRoadmap For 2023 - 2030creativejoburgNessuna valutazione finora

- Betty NeumanDocumento3 pagineBetty NeumanGeovanni Rai Doropan HermanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Epi Lecture 1 Part IIDocumento36 pagineEpi Lecture 1 Part IIMowlidAbdirahman Ali madaaleNessuna valutazione finora

- AHM 250 SummaryDocumento116 pagineAHM 250 SummaryDinesh Anbumani100% (5)

- CHN P1 ExamDocumento23 pagineCHN P1 ExamNicholeGarcesCisnerosNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 May CHN CD 1 TeamsDocumento8 pagine2022 May CHN CD 1 TeamsCrystal Ann TadiamonNessuna valutazione finora

- MNJDocumento24 pagineMNJWazzupNessuna valutazione finora

- Level of Knowledge and Attitude Among Nursing Students Toward Patient Safety and Medical ErrorsDocumento125 pagineLevel of Knowledge and Attitude Among Nursing Students Toward Patient Safety and Medical ErrorshanadiNessuna valutazione finora

- NHMRC VTE Prevention Guideline Summary For CliniciansDocumento2 pagineNHMRC VTE Prevention Guideline Summary For CliniciansRatnaSuryati100% (1)

- Aapi Ebook v2 FinalDocumento201 pagineAapi Ebook v2 FinalAAPIUSANessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction and Around The World W Dr. Boyd": COVID-19 ResourcesDocumento10 pagineIntroduction and Around The World W Dr. Boyd": COVID-19 ResourcesNabillahNessuna valutazione finora

- Expanding Mental Health Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From Initial Experiences in Lubombo RegionDocumento8 pagineExpanding Mental Health Care in The Kingdom of Eswatini: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations From Initial Experiences in Lubombo RegionCOMDIS-HSDNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Development Approachesto Health PromotionDocumento35 pagineCommunity Development Approachesto Health PromotionGlenn L. RavanillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Healthy Lifestyle EssayDocumento11 pagineHealthy Lifestyle EssayAlexsion AlexNessuna valutazione finora

- National AYUSH MissionDocumento107 pagineNational AYUSH Missionsheetal kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Health10 Q4-Mod4 DecidingOnAppropriateHealthCareerPathDocumento29 pagineHealth10 Q4-Mod4 DecidingOnAppropriateHealthCareerPathJM MendezNessuna valutazione finora