Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chin - Ethnically Correct Dolls

Caricato da

Sofía Janampa SantomeDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chin - Ethnically Correct Dolls

Caricato da

Sofía Janampa SantomeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ethnically Correct Dolls: Toying with the Race Industry Author(s): Elizabeth Chin Reviewed work(s): Source: American

Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Jun., 1999), pp. 305-321 Published by: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/683203 . Accessed: 09/11/2012 17:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley-Blackwell and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Anthropologist.

http://www.jstor.org

ELIZABETHCHIN

Departmentof Anthropology OccidentalCollege Los Angeles, CA 90041

EthnicallyCorrectDolls:Toyingwith the Race Industry

andinclusionin the toy box, solutionto representation has toutedethnicallycorrectdolls as a progressive The toy industry blackchildrenin New Haven,Conpoor andworking-class work with ten-year-old, s lives. Ethnographic and in children' necticutcomplicatesthese assertions.These childrenhad very few ethnicallycorrectdolls. Instead,girls had white dolls a case studyof thatthey broughtinto theirworldsthroughstylingtheirhairin ways raciallymarkedas black.Contrasting look at race andcommoditiesamong New Havenkids, this paperlocates chilMattel's Shanidolls with an ethnographic Taka contextexaminedin few studiesof toys or consumption. withinthe contextof social inequality, dren'sconsumption subjectssuggestsways in whichthis largelysilencedgroupcan speakto largersocial and ethnographic ing kids as primary consumption] socialinequality, U.S.anthropology, issues, amongthemrace,class, gender,andage. lchildren, theoretical

Entering the Race Market

in 1992, amidstprodigiousswelter.A A July afternoon summerday: hot, gluey typical New Haven,Connecticut, air slowly being stirredby an unenthusiasticbreeze. In andpoorAfncan American Newhallville,a working-class neighborhood,most had abandonedeven shady porches living rooms.By threein the afterfor the cooler,darkened noon, the air had stilled and the sky clogged with soggy, Nataliaand with ten-year-old gray clouds. As I sat taLking her cousin, an invigoratedwind suddenlybegan twisting leaves off trees and the sky erupteddownward,dumping marble-sizedraindropsupon the streets and stoops and rooftops. Thunderoverpoweredour voices. Braving the rain and lightning,the girls rushedout to Natalia'sstoop, hopping about like gazelles when the thundershook the small wood-framehouse: a thrill!I spied a frazzle-haired, white Barbiedoll beneathNatalia's seat, and holding my askedthe girlsto tell me abouther.Withthe taperecorder, fromtheirchairs,Natalia thunder jolting themperiodically the machineandbeganto speak: arldAsia commandeered

ASIA: You never see a fat Barbie.You never see a pregnant Barbie.Whataboutthose things?They shouldmakea Barbie thatcan have a baby. NATALIA:Yeah . . . andmakea fatBarbie.So when we play Barbie. . . you could be a fat Barbie. ASIA: OK. WhatI was saying thatBarbie. . . how can I say this? They make her like a stereotype.Barbieis a stereotype. When you think of Barbieyou don't think of fat Barbie . . . Barbie.You never,ever . . . think you don't thinkof pregnant of an abusedBarbie.

"I Nataliaannounced: Speakinginto the tape recorder, would like to say that Barbieis dope. But y'all probably don't know what that means so I will say that Barbie is was the girls' conduitto an imaginice!"The taperecorder nary audience, one located outside their own neighborthe bland hood, and one that is not black. In substituting and inoffensive word "nice"for the tastinessof "dope," a devastatingsensitivityto the gap Nataliademonstrated between her own world and the one where the "y'all" why therewasn'ta live. In wondering whomshe addressed Nataliaand or "abused," Barbiethat is "fat,""pregnant," Asia also wonderedwhy these dolls representsocial and worldsso foreignto them. cultural In 1991, a year beforethese girls spoketheirminds,the theirfirstethnicallycormakersof Barbiehad introduced rect fashion dolls to the market.Ostensiblymeantto adalludedto in dressthe problemof minorityrepresentation ShaniandherfriendsAsha NataliaandAsia's interchange, andNichelle were unlikeotherblackdolls Mattelhadproduced:they came in light, medium,and darkskin tones; based they hadnewly sculptedfacialfeatures(purportedly on real African Americanfaces); and there were reports repthattheirbodieshadbeen changedto moreaccurately figures.Thesetoys were designed resentAfricanAmerican dominated specificallyto reshapea territory and marketed they by an assumptionof whiteness, but paradoxically, the toy worldwhile at the sametime fixing haveintegrated arebased morefirmly.Theseboundaries racialboundaries andskin hairtype,facialfeatures, markers: uponracialized color; toymakerslike Mattel assiduouslyavoid delving into the social issues thatNataliaandAsia identifiedas beEthnically correctdolls ing centralfrom theirperspective.

1999, AmericanAnthropologicalAssociation 101(2):305-321. Copyright(C) AmericanAnthropologist

306

* VOL. 101, NO. 2 * JUNE1999 ANTHROPOLOGIST AMERICAN

do not address Natalia's and Asia's questions about fat, or dope Barbiesany morethantheir abused,pregnant, did. white counterparts In Newhallville, however, girls tended to have white dolls thatthey workedto bringintotheirown worlds,often highlightchilhair.Theseinteractions throughstylingetheir dren's understandingthat racialized commodities like Shani can only incompletelyembody the experiencesof kids who arenot simplyracialbeings,butalso poor,working class, young, ghettoized,and gendered.Embodiedin these children'sactivities is a profoundrecognitionthat to be but has potential race is not only sociallyconstructed The situationin Newhallville reconstructed. imaginatively of ethnicallycorrecttoyposes problemsfor the assertions makerswho arguethatkids of color play betterwith dolls that "look like them." Girls in Newhallville worked on racialaband symbolically,blurring theirdolls materially solutes by putting their hair into distinctively African Americanstyles using beads, braids,and foil. These approachesto the questionof race and dolls suggestways in which feministnotionsof multiplesubjectivityand queer theory ideas aboutthe flexibility of designationssuch as or "gay,""girl"and "boy"are relevantto the "straight" of study of race and racism.In looking at the interactions Newhallvillegirls and theirwhite dolls, ways of thinking between and outsideof boundedracialcategoriesemerge. of these girls' playfulefforts potential However,the radical is just that: potential, since Asia and Natalia- like the by otherkids in theirneighborhood live lives constrained of socialinequality. the contingencies aftermy fieldThe questionof dolls becameimportant I had work was over, when I realized that photographs takenshowed,over andover again,black girls with white braided, twisted,or dolls whose hairhad been elaborately styled in ways racially markedas black. Understanding weremeantlookingin severalterriwhattheirimplications tories.On the one hand,white dolls with blackhairdosrequired looking into the ethnically correct toy industry, for childrenlike since these toys have been manufactured Nataliaand Asia. In a portionof this paper,I look at the ethnicallycorrecttoy industfy,takingMattel'sShanidolls as a case study.But few childrenin Newhallvillehad such dolls, and their importancein these kids' lives was as much if not more in theirabsenceas in theirpresence. The social, economic,historical,and politicalfactorsthat have engineered the absence of ethnically correct toys from Newhallville children'srooms are the same forces andemthathave helpedto formpoor,raciallysegregated, battledcommunitiesin urbanareasacrossthe nation.It is preciselyin the contextof encompassingand multiplesocial inequalitythat ethnicallycorrecttoys like Shani and white dolls need to be Newhallville'sraciallytransformed understood.This is a context breedingsilence, and kids like those I knew in Newhallvillerarelyspeakor areheard beyond their sequesteredsphere.I cannotclaim that this

or thatit paperis itself the speechof Newhallvillechildren, speaksfor them. However,the engaged,culturallyactive, and talkof and at times cntical expenences,observations, for understanding Newhallvillechildrenarethe foundation why white dolls with braidshave a profoundand potentially radical meaning that confounds the commercial rhetoncof ethnicallycorrecttoys like the Shanidoll.

Learningfrom KidsaboutRace,Consumption, and the Questionof Queer

andculto corporate This papermoves at once outward turalpolitics and inwardto children'spersonalterntones. beThis dual focus serves first to stress the relationship thathas a relationship tween commoditiesandconsumers, been somewhat neglected until recentlyin anthropology also engagesrecentworkon approach (Miller 1995). I^his identitythatemphasizesit as a processthatis flexible, dynamic,andmultifaceted.l between commoditiesand consumers The relationship is particularlyclear when it comes to the question of Americanchildren.Since the latterhalf of the nineteenth century children have been increasinglyexcluded from activitiesandredefinedas pasin productive participation the range and persive and dependent.Simultaneously, of equipmentand technologyfor chilceived importance (Aries has proliferated dren'seducationandentertainment psycho1962; Cross 1997). ErikErikson'sworkfeaturing therapywith innocuoustoys helpedto instill a sortof awe and terror about children's play: dollhouses and dolls, blocks,carshave not been the same since (1964). Coupled with Maria Montesson's dictum that "play is a child's work"([1912]1964), toys and play have come to hold increasingimportancein Americanchildren'slives and in theirfamilies' concerns.Partof the result:toys are now a business. $17-billion-a-year are placing a growing Some psychologicalresearchers relationship or interactive, on the transactional, importance between kids and theirplaythings(see Kelly-Byrne1989 point example).The transactional for a rareethnographic of view rarely emerges in the two most common approachesto the questionof kids and toys. One such approachfollows fromErikson'sworkand focuses on kids' (Calplay, castingtoys as relativelystaticand transparent deraet al. 1989; Henryand Henry 1974). In these works, or pocultural, the historical, do not investigate the authors producing liticalcontextof eitherthe toys or the industries them,and rarelyof the childrenplayingwith them (an exfocuses almostex1986).Another ceptionis Sutton-Smith clusively uponthe toys themselves,withoutsystematically with examininghow childrenactuallyrelateto andinteract them.2Although some have stressed the importanceof studyingchildrenwho are poor or from ethnic and racial 1986), andJones 1994;Sutton-Smith (Pellegrini minorities

DOLLS CORRECT CHIN / ETHNICALLY

307

children studiesthatarenot focusedon white,middle-class arefew andfarbetween.3 Queer,feminist,and culturalstudiesanalyseshave alreadyyieldedincisivecritiquesof Barbieandherilk, ethniThese analyseshave moved cally correctand otherwise.4 well beyond the shopwornobservationthat Barbie, with her sadisticallypointedbreasts,waspy waist, and permanently high-heel preparedfeet,5does not look much like any realwomanwho has not hadextensiveplasticsurgery. has limitationssimilar to those discussed This literature history of the Americandoll, Miriam a social in above: chargesthat "atbest, feministscholars Formanek-Brunell dolls by the Franrt School) haveinterpreted (influenced culturein which girls as agentsof a hegemonicpatriarchal are passive consumers"(1993:1). Like most studies of research andmarketing (consumer Americanconsumption excepted),the great majorityof Barbie analysesproceed withouttalkingto or observingchildrenthemselves,and skirt so to speak issues of race and class. Child-centered researchis needed partlybecause what childrendo in current,adult-centric and say is largely unanticipated This appliesas much frameworks.6 analysesor theoretical to work focusing on childrenand theirlives as to thatexof childrenand aminingsociety at large:the ethnography holds potentialfor childhood,like feminist ethnography, thinking. anthropological transforming In the Barbierealm,the workof EricaRandis an importantmodel for how to thinkcriticallyabouttoys, children, and culture-even thoughshe explicitlyexcludeschildren QueerAccessofromthe scope of herinquiry.In Barbie's ries (1995),Randhas collected women's recollectionsof Barbiein theirlives. Randis explicit and clearthatadults of obrecallingtheirown childhoodsarenot the equivalent the servancesof actual children.Her book demonstrates thatchilwhile emphasizing power of adultremembrance through dren's experiences cannot fully be recuperated approaches. adult-centric aspectsof Rand'sanalyOne of the centrallyimportant the notion of queer.In conceptualizes way she the sis is Barbiequeer is not making Accessories, Barbie'sQueer necessarilyaboutsex or sexuality.Rand'snotionof queering highlightsthe bending,twisting, or flippingof apparor acceptedsocial states,and she exently real or natural plores a variety of ways in which Barbie gets queered: G.I. consumeractivistsswitch the voice boxes of taLking Barbie, adult women remembercrossJoe with taLking dressingBarbieor makingherfuck Midge, 'zines generate faux ads for such items as AIDS Barbie.The fundamental tensionis betweena commoditywith a packagedidentity andthe consumerswho put herto workin theirown lives; of the deliciousnessof the images is their transgression profile. Barbie managed Mattel'scarefully As radicalas these queeringsmay be in a given cultural space and social moment,they also make use of andtake

place within powerful ideological discourses:transgresX sion does not make up its own rules, or exist in a world apartfrom hegemonicinfluences,and the power of resis(Brown1996;Sholle 1990). tanceshouldnot be overstated we look at resistance when has argued, Abu-Lughod As and the sites where it emerges, we stand to learn more of power than arenasof freedom(1990). about structures of one of her own BarbiequeeringsilRand'sdescription the ways in whichthe layeredandmultiplemeanlustrates ings of race, sexual identity,and gendercan reflectback effect in which upon each other,creatinga hall-of-mirrors In positioning the subversionsuddenlyis itself subverted. dyke sex scene"between two dolls in a staged"toptbottom Barbie(which,according herWhiteBarbieand"Chicana" to the package was an "AmericanIndian"Barbie) she writes: Putwithhowto assignrolesto my two Barbies. I struggled of the stereotypes racial ontopreinforces Barbie tingChicana whitegirl;the the less animalistic overpowering darkbrute aloneplacesmy Dream Lof} firmlywithinthe haircontrast which of lesbianrepresentation, tradition hetero-generated a seducing vixen dark-haired an aggressive, often features subhave would top on Barbie blond Putting innocent. blond In whitesupremacy. butperformed thesestereotypes verted discourse. termsof race,therewas no way out of dominant [1995:172-173] In Newhallville,Natalia and Asia used a considerably similarconcerns to articulate more condensedvocabulary why thereis no They wondered aboutBarbie'slimitations. Barbie,questionsthatwere shaped fat, abused,or pregnant by theirbeing youngblackgirls living in a poorandworkThese multiing-class, raciallysegregatedneighborhood. nor ple facetsof kids' identitiesarefixed neitherinternally socially; elsewhere I have examinedhow differentgeoand relevanceof the relationship graphicsites reconfigure (Chin experience gender, race, and class in children's 1998). These shiftsareconnectedto the creationor restriccan takeplace:in theprition of spacesin whichresistance vacy of their homes, girls are safe to indulge in childish streets,suchchildishvulnerabilplay;in the neighborhood aimedat fendingoff ity is replacedwith a vigilantbravado in downtownstores,sexualdangeris transsexualdanger; fantasy,andthe vigilancemoves onto mutedinto romantic racialground. Despite a growing literatureexamining hybridityor mixed-raceethnicityand identity,in the U.S., discussions and analyses of race tend to make use of a polarized black/white framework,as Hamson notes (1995). The the errorof "reproduce problemis thatstudiesof hybridity misplaced concreteness"in Brackette Williams' view (1995), basing notions of mixture on still-problematic categories.Similarly,Peter Wade has arguedthat "pure" the basic ideas of phenotypeand differencehave not yet

308

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST * VOL. 101, NO. 2 * JUNE1999

been sufficientlyrecognizedas beingthemselves historical, Western,andcolonialconcepts(1993). Ethnicallycorrecttoys drawupon these notionsof difference and phenotype,paradoxically makinguse of oppressive distinctions to create progressivechange. The braidedheads of white dolls in Newhallvilleat least make a dent in the concretenessof race boundaries. Neitherhybridnor multicultural, they areinsteadqueer.Seeing these dolls as raciallyqueeredis appropriate not only because naturalized categoriesof race are being bent, but also because it is a notion which, unlike hybridity, is fundamentally playful. Play is conceptuallycomplex and sophisticated:"Howdoes a dog know a playbite froma realbite?" asked Gregory Bateson in a well-known essay ([1955]1972).Insteadof Bateson'splayfulbite,these children have made a play on whiteness.Race thathas been queeredin this way challenges "pure" forms by disconnectingracialmarkers fromparticular bodies, muchin the way that queer and gender studies have recognizedthat genderand sexualityare not inherently, predictably, or inevitablyrootedin physical"male" or "female" individuals. Theseplayfullyimagined,resistant realitiesarenot separable, however,fromthe contextof discrimination, segregation, andoppression in which they have been generated, to which they ultimatelyrefer, and with which they remain enmeshed.

Negotiating Newhallville

A host of terrifyingstatisticscan be employedto illustratethe harsheconomic contrastsand racialtensionsthat characterize New Haven today. Locatedin the wealthiest of the fifty statesin termsof percapitaincome,this city of 130,000 was in 1980 the seventh-poorest of its size in the nation(U.S. Bureauof the Census 1980).Despitethe nearness of Yale-New Haven Hospital's internationally renownedinfantandchild facilities,some neighborhoods in the city have infant mortalityrates in excess of 66 per 1,000 (Regueroand Crane 1994). Since the l950s, New Haven has lost over 20,000 manufacturing jobs, and the Winchester Repeating Arms factory in Newhallville, whichonce had 12,000 workersworkingthreedaily shifts, now employs less than 500. Local commercehas shifted from being factoxy-based to being dominatedby service jobs, the drugtrade,and governmentaid. Newhallvilleis almost completely segregatedand has a 91.7% minority population, but it bordersthe richest(and whitest)neighborhoodin town. Newhallvillekids' sense of dangerandpossibility and the themes of their playfulness-changed dependingon the location.Downtown,the atmosphere was chargedwith racialtensions,but girls' romanticfantasiestook wing. In contrast,theirneighborhood was a raciallysafe and sexually dangerous place, one wherethe proprietor of the corner storewatchedthem with the criticaleye of an irascible

grandparent, and whereteenageboys and oldermen were seen as threatsbut increasingly interesting. Not trusting in my abilityto negotiatethis terntorywith success,the girls took to escortingme out of the area,guidingme paststores, streets,and people. One summerafternoonwhen Natalia decided I had let an impromptu conversation with a man last too long, she deftly cut the interactionshortz"He's probably a drugdealer," Nataliasaid with assurance as we walked away. "He probablyrapes little girls."For Newhallville girls, the concernsaboutrapeand pregnancy begin early.Rape andpregnancy areissues relevant to all femalesbutactivelynegotiating themat the age of ten is less the impactof gender,perhaps,thanit is of class, race, social, and economic issues.7These concerns,arisingfrom actualexperienceof abuse,reportsof friendsandrelatives, close brusheswith olderboys and men in the street,were and continue to be real. Although she was not raped, Nataliabecame pregnanttwo years afterthe Barbieincident and delivereda baby girl when she was scarcely 13 yearsold. Sometimes,as they were aboutto entertheirhomes,the girls would pauseby the backdoor or frontstoopandpretend to terrifythemselves with stories of "PeanutButter Man,"a mythicalconvict who had escapedprisonwith a gun his mothergave to him, slippingit pastguardsby hiding it in a jar of peanutbutter. These tales emphasized that in contrast to the streets,theirhomes were placesof safety where girls could still be like little kids. Doll play, as Natalia'scousinAsia pointedout, was a sign of beinga little kid. "We might play with Barbieslike this,"she said, miming the way kids bounce a doll along a tabletopto make it walk, "butwe don't let anybodysee us." At ten years old, these girls had limited childish vulnerability to the interiors of their houses, whose windows were shrouded by shadesandcurtains. Boys theirage still gathered togetheroutside on stoops to play with their action figuresand vehicles. Whetheror not the girls playedwith theirdolls much,theirfamiliesstill gave themdolls,as if to underscore the girls'continuing statusas children. In 1992, Natalia's big Christmasgift from her motherwas a lifesized battery-powered doll thattalkedandsuckeda bottle. "Itcost $60," Nataliatold me. Throughmuch of the day, she held the peachy-skinned, platinum-blonde doll on her hip and called it her "brat."Though the whiteness of Natalia's "brat" was striking,she never mentionedit and was most impressedwith its cost and the novelty of its voice recognition technology. Only once duringmy fieldworkdid a child makean issue out of her dolls' race. In early October,as Tionna's birthdayapproached, she told me that she wanted some black dolls. "Why?" I askedher. She explainedthatat the momentshe hadmorewhitedolls thanblackdolls andshe wantedto even out the numbers."Afterthat, I'll get anotherwhite doll, and then a black doll, like that,"she explained.Why, I wondered, hadn'tTionnagiven an answer

CHIN /

ETHNICALLY CORRECT DOLLS

309

thatwas morein line with the marketing andadvertising of ethnicallycorrectdolls, which madesuch claims as "Kids have more fun with dolls thatlook like them"?Partof the explanation lies in the dangersof wishing.In Newhallville, kids learnearlyto expresstheirwantsandwishescarefully, ratherthan candidly.Kids are well awarethat their family's resources are not limitless and keep their requests modest.Carlos,for example,explainedthatbeforeChristmaseach yearhe gives his mothera list of thingshe'd like, andknows thatthose arethe thingshe will receive.The list he showed me consisted of five toys, none costing over $20. I regularlyasked Newhallville children what they would do if they found $20, and nearly all of them said they would give some or all of it to their mothersto buy groceries,or pay the rent.As Devon said, "Theyhelp you, why shouldn'tyou help them?"In groupinterviewswith middle-classchildrenat a privateschool, none said they would give any of the money to theirfamilies, optinginsteadto "Putit in the bank!" or "Buytoys!" Whining,throwingtempertantrums, or otherattempts at coercion were usually dealt with harshly, and in Newhallville child discipline was generallyboth swift and physical. On several occasions children returnedhome from a trip to the supermarket or downtown with tearstreakedfaces, havingbeen punishedfor "actingstupidin the store,"as one mothersaid. In this and othersettings, kids learnedearly andwell thattheirown desireshad serious effects upon their caretakers and other family members,thatthey were expensiveto house and feed, andthat whateverthey got usually meantsomeone else had to do without.I spent endless hoursin malls and in storeswith childrenand never heardthem say "I want that,"unless they had money of theirown in theirpocketsandcouldactuallybuy the thingthey wanted.Theirconcernseven extendedto my own finances,andwhen I wouldofferto buy a child a soda or ice creamcone, they often declined.As Tarelle explained, "I don't want to spend up all your money,Miss Chin." Even gettingto the stores in orderto buy the toys was difficultandexpensive.Nearlyhalf of Newhallvillehouseholds did not have a car; friendsand relativescould provide rides,but often chargedfor "gasmoney."The nearest Toys "R"Us was all but inaccessibleby public transport andcould only be reachedby takinga highwayto the next town. Most kids I knew in Newhallvillevisited it at most only once or twice a year.Some hadneverbeen there.The downtowntoy store,Kaybee,specializedin overstockand discontinued items. It hadhigherpricesthanToys "R"Us, was a fractionof the size, and offereda small and unpredictable selection of toys. Other places to buy toys included the supermarket or discountchains such as Caldor's, and several children cited these as their favorite stores.

Tionna, likemany of herpeers, hadnearly fullyincorporatedthe lessonthatshe shouldharbor few expectations andmakefew demands. OnChristmas morning, in 1992, Tionna got up earlyandranto look under the tree.She didn'tsee anygifts.Thinking thatthere justweren't any giftsthatyear,she wentbackto bed.There were presents, shejusthadn't seenthem. Butdespite herfierce(if temporaty)disappointment, Tionna accepted thepossibility that therewereno presents at all because the possibility was real. Theprimaxy appeal toy makers offerwiththeireffinicallycorrect playthings is theideathatsuchtoyscanhelp minority kidsto feel moreathomein theworld through allowing themto playwithtoys-and especially dolls that looklikethem.Ina community where kidscanaccept the ideathat Santa justdidn't comethisyear, having ethnically correct toysontheshelves of Toys"R" Us seemsunlikely to havemuchimpact. By framing therepresentation problemas beingoneonlyof race,makers of ethnically correct toysmississuesthatforNewhallville children wereoften more immediately pressing. Despitethe overtphysical changes thatMattel madewhentheyproduced Shaxii, she still inhabits a farltasy worldremarkably similar to Barbie's,theworldwherethe word"dope" mustbe replaced with"nice" astheproduct packaging shows:

Shani, Asha, and Nichelle invite you into their glamorous world to sharethe fun and excitementof being a top model. Imagine appearingon magazine covers, starringin fashion shows, and going to Hollywood partiesas you, Shani,Asha, and Nichelle live your dreamsof beautyand success, loving everymarvelousminute!

The Unbearable Whitenessof Barbie

Welcometo OurWorldof OLMECToys. Almost seven years ago, my son sent shock waves through my body when he said he couldn'tbe a superherobecausehe wasn'twhite. "What!" I thought.At the tenderage of three,my boy was alreadylimitinghis fantasiesbecausehe thoughtsome dreams didn'tcome in his skincolor. Thatwas my inspiration to createSun-Man, the world'sgreatest superhero.Since then we at OLMEChave expandedinto girls andpreschooltoys. We've got one thingin mindwith all ourproducts let's buildself-esteem. Ourchildrengain a sense of self importance through toys. So we makethemlook like them. Now that he's 10, my son's dreamsand goals soar. Playing with toys thatlook like him makeshim feel good. I hope you'll buy somethingfrom us that will expandyour child's dream.[product packaging, Olmectoys]

310

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST * VOL. 101, NO. 2 * JUNE1999

Stories like the one that Yla Eason, Olmec's founder, has printedonto the packagingof many of her company's productsare pervasive among minoritytoy makers and emphasizethe deeply personalmotivationbehindthe corporateentity.Companies suchas Olmechave a focusedsocial and politicalagendaaimedat undermining the racism endemic to an industrythatseemed to espouse the notion that all baby dolls and Barbies andby implication,people-ought to be white.The genesis of these toys has been in the crucibleof urbanracialstrife:the nation'sfirst minority toy maker,Shindana,was foundedin the wake of the Watts riots with Federalmonies and a start-upgrant fromMattel. Olmec's statementthat "Ourchildrengain a sense of self-importance throughtoys. So we make them look like them"bears a heavy debt to the revelationsthatemerged fromthe groundbreaking "dollstudies"conductedby psychologists Kennethand Mamie Phipps Clark in the late 1930s andearly 1940s.These studiesused blackandwhite dolls as a way to unearth blackchildren'sviews aboutrace, asking them to point out, for instance,which doll "looks nice." In a series of devastatingpublications,the Clark studiesrevealedthatblackchildrenoftenthoughtthe white doll "looksnice," while the blackdoll "looksbad"(Clark andClark1939, 1947).8 The Clarksarguedthatblackchildren prefemng white dolls could be seen to be suffering from "self-rejection" or "self-hatred." However,the impetus for these feelings was not intemallygenerated. Rather, the Clarks'view was thatkids understood all too well that the largersociety denigrated anddevaluedblacks.As a result, children's feelings about themselves were complicatedby this knowledge.The doll studiesgainedadditional clout when theybecameassociatedwiththe landmark civil rights case Brownv. theBoardof Education of Topeka, Kansas,in which the Supreme Court ruled segregated schoolingto be unconstitutional.9 Olmec's Sun-Manfigure seems to be a directresponse to the Clarkstudies,andupendsracialhierarchy by making darkskin a sourceof powerrather thanone of oppression: he gets his super-hero abilitiesfromthe melaninin his skin. The central motivating moment that Eason recounts is when her son Menelik announced"some dreamsdid not come in his skin color." The wording of this statement, which is printedon most Olmec packaging,effectively marries MartinLutherKing's civil rightsoratory("IHave a Dream")with the startling discoveriesof the Clarkdoll studies(the Negro doll is ugly/bad)to providea powerful argumentfor the need of dolls that accuratelyand positively portray blackness. Olmec is not alonein attempting to connecttheirtoys to the visceralpowerof the Clarkstudiesandthe moralforce of the civil rights movement. Mattel recnaitedthe psychologist Darlene Powell-Hopsonas a consultantin designing the Shani dolls. Powell-Hopson,who had replicated the Clark studies in the early 1980s, found that

children'sperceptionsof race had hardlyimprovedsince the 1930s (Powell-Hopson1985). A key element of her replication of the Clarkstudieshadbeennew:the studydesign includedan intervention aimed at children(white or black)who did not have positivevalue assessmentsof the blackdolls. In thesecases,the researcher demonstrated that she valued the black doll and found it beautifulor good. Powell-Hopson'sresultsshowedthatthe intervention was largelyeffective (at least in the shortrun),and the Shani dolls were shapedby theseresults. The involvementof Powell-Hopson in the development of Shani dolls provideda direct line of descent from the work of the Clarks,connectingthese productsto social movements and historical moments of national scope. Shanihas been moldedon a set of assumptions harkening back to the Clark studies, but with a commercialtwist: childrenwho play with dolls thatlook like them will not suffer from self-hatred.The message that manufacturers offer is "Buy toys that represent racialdiversityand your childrenwill be empoweredas racialbeings,not overpowered by racism."With ethnicallycorrecttoys, the logic of the Clarkstudiesis reversed: it is the toysthatareresponsible for children'sperceptions, not the societythatproduces them. Withthe introduction of Shaniandherfriends,even the makersof Barbieherself have recognizedthe unbearable whitenessof Barbiein minoritychildren'sexperience.A morecynical assessmentof both Olmec andMattel,however, might questionwhich the companiesfind more unbearable: the Eurocentric toy industry or untapped market segments.Moreover,the type of diversitythathas developed in the toy industry'sproductsis far from being unproblematic; while mountinga challengeto whitenessas a norm, the diversity currentlyunder manufacture in the form of "ethnicallycorrect"playthingsdoes not significantlytransform the understanding of race,or even racism. Rather,ethnicallycorrectdolls refashionracistdiscourses andmarket themto minority buyers. One of the problemswith all these overtandcovertreferencesto the civil rightsmovementis thatthey ultimately appealmoreto parents-or grandparents thanthey do to kids themselves.In Newhallvaille,dolls did not seem to be a flashpointof racial tension for kids, though themes of race were certainly present. One afternoonas I visited Takeina,a classmateof TionnaandNatalia,I askedher to tell me aboutthe black Barbiesthatshe had flung, naked andwithmaKed hair,intoherdollhouse.My requestgenerated little interestfrom her eitherin talk or play. A little while later, however, her older brotherand a friend had joined us. The subjectof race came up again,and I asked themto tell me how white people talk.The childrencould hardlycontainthemselves, and practicallyfell over each other trying not only to imitate white people's talk, but their physicality. Adopting a gangling, uncoordinated

CHIN /

ETHNICALLY CORRECT DOLLS

311

swagger, her brotherdrawled,"Let's go to the mall and buy some rags." For Newhallville kids the mall was a raciallycharged space where they felt embattledand unwelcome (Chin 1996, 1998). Takeina's brotheridentifies the mall as a place for white kids to go and buy "rags."New Haven's downtown mall is permeatedby measuresto discourage poorandminority shoppers (who areoftenviewed as being synonymous):bus stops have been moved away from the mall, FrankSinatradominatesthe sound system. Unlike mall management, manufacturers of ethnicallycorrecttoys have not made the mistakeof assumingthat all minority consumersare poor:the marketfor ethnicallycorrecttoys has been explicitly built upon the buying power of the black middle class. Ebony magazinepress materialsprovided at a toy industry event in 1993 estimatedthatblack consumersspent $745.6 million on toys the year before. While this strategyis soundbusiness practice(marketing

toys to the pooris unlikelyto generate muchrevenue althoughmarketing cigarettesand malt liquorseems to pay off prettywell), it forcesmanufacturers into an uncomfortable position.Toy executivestold me time and againthat these toys are good becausethey servean important social function, but it is not their responsibility to make these products availableto economically disadvantaged kids.

Shani and the Marketing of Blackness

The signature aspectsof ethnicallycorrectdolls areresculptedfaces, skin tones, hair types, and ethnic fashions. Untilcompanieslike Shindana andOlmecjump-started the mass production and marketing of ethnicallycorrecttoys, mass-produced blackdolls werebasicallymadeby pouring brown plastic into the same molds used to make white dolls. This was and continuesto be a powerfulmaterial demonstration of an assimilationist ethic,one thathas been rejectedwith growing vehemenceby ethnic groupswho

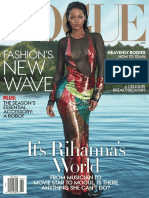

Figure 1. Barbie and Shani from behindb Photo by ElizabethChins 1998.

312

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST *

VOL. 101, NO 2

* JUNE 1999

are, increasingly,no longer numericalminoritiesin their communities.While these toys do celebrateand enshrine differencein a way thatprecedingblack dolls andtoys do not, the emphasison the visibilityof race as a collectionof markers masksthe complexityof racebothas a social constructandas a socialexperience. by Mattelin 1991 re The Shaniline of dolls introduced feaconsistingof phenotypical duces raceto a simulacrum tures:skin color, hair, and butt. Ann DuCille (1996) has nature, discussedmuchof theircomplex andcontradictory andhair.Accordhighlightingtwo centralissues: derriere ing to DuCille's interviewswith Shanidesigners,the dolls to give the illusionof a higher, have been re-manufactured rounderbutt than other Barbies. This has been accomplished,they told her,by pitchingShani'sbackat a differof herhips. ent angleandchangingsome of the proportions at the colfromstudents I hadheardtheseandotherrumors lege where I teach: "Shani'sbutt is biggerthanthe other Barbies'butts,""Shanidolls have biggerbreaststhanBarbie," "Shani dolls have bigger thighs than Barbie.''l? an DuCillerightlywonderswhy a biggerbuttis necessarily attribute of blackness,tying this obsession to turn-of-thecenturystrainsof scientificracism.

DecidingI had to see for myself, I pulledmy Shanidoll hernaked,andplacedher off my office bookshelf,stripped on my desk next to a nakedBarbiedoll thathadbeen crus dog (herarmswerechewed by a colleague' elly mutilated wounds,butthe restwas unoff andherheadhadpuncture the dolls in ways harmed).Try as I might, manipulating both painful and obscene, I could find no differencebetween them,even afterpryingtheirlegs off and smashing As far as I have been able to determine, theirbodies apart. Shani's bigger buttis an illusion (Figure 1). The faces of thantheir ShaniandBarbiedolls aremorevisibly different behinds,yet still, why these differencescould be considAs a friendof indicators of raceis perplexing. erednatural mine remarkedacidly, "They still look like they've had plastic surgery."The most telling difference between whereShani ShaniandBarbieis at thebaseof the cranium, ironscar:O 1990 bearsa raisedmarksimilarto a branding MATTELINC. Barbie'shead reads simply C)MATTEL INC. Despite claims of redesign,both Barbieand Shani's andalthoughDuCilleasserts torsosbeara 1966 copyright, thanBarbie's,their thatShani'slegs areshapeddifferently legs are imprintedwith the same part numbers.This all strongly suggests that despite claims and mmors to the

in threedifferentface molds and skin tones. Fromleft to right:Nichelle (dark),Shani (medium),and Figure 2. The Shanidolls are manufactured Asha (light). Photo by ElizabethChin, 1998.

CHIN /

DOLLS CORRECT ETHNICALLY

313

contraw, Shani and Barbie are the same from the neck down. one of the Ttlese ethnicallycorrect dolls demonstrate abidingaspectsof racism:thata stolidbelief in racialdifthat so profoundly ferencecan shapepeople's perceptions of it, no matthey will find differenceandmakesomeffiing its physicalmanifestaor irrelevant ter how imperceptible tion mightbe. If I hadto smashtwo dolls to bits in orderto see if theirbuttswere differentsizes, the differencesmust be small indeed:holdingthem next to each otherrevealed no difference whatsoever cxcept color-regardless of the positioning(crackto crackor cheekto cheek).Withthe buttindex so excmciatinglysmall, its meaningas a racial Like the noproblematic. signifierbecomes frighteningly tion of race itself, Shani's derrierehas a social meaning to its scientificmeasurement. thatis outof all proportion The Shanidolls, with theirlight, medium,anddarkskin kindsof blackness tones,weredesignedto signifydifferent (see Figure2). The progressivenotionthatblackdoes not look just one way is not as progressiveas it mightappear whenone looksclosely at the Shanidolls, whosefacialfeathe darker "black" turesseem to get more stereotypically doll, has the the doll's skin color: Asha, the light-skinned smallest nose and ffiinnestlips; meanwhileNichelle, the doll, has lips thatare muchwiderthanthe outlines darkest pink lipstick,andhernose is the largest of herstamped-on andwidestof the Shanidolls. Lightas Ashais, she is not so light that there is any danger that she might be able to as white. "pass" In the mindof at least one Newhallvillechild,the meaning of the varlousskin colors was not kinds of blackness, kinds of racialmixing. WhenCarlosandI were but rather in Toys "R"Us, I pointedout to him thatthe dolls came in threeskin tones. As I held one of each color in my hand, beganto describethem."She'sAfriCarlosspontaneously can American,"he said, about Nichelle, the darkesthe said, referring skinneddoll. "She mustbe partIndian," or a light-colored Puerto Rican to Shani."Thisone is like black person,"he finished, as he examinedAsha. When Rican or a lightCarlosdescribesAsha as being "Puerto colored black person"he capturesthe difficultyin being able to know race simply by looking. His commentalso in U.S. racialcategohighlightsthe logical inconsistencies ries, which would in fact (accordingto the U.S. Census) classify Asha's human counterpart as being either Thatis, as or "Hispanic." "black not of HispanicOrigin" is concerned,her race wouldbe defar as the government but by geography terminednot by genetics or parentage, and history. This issue was close to home for Carlos, a PuertoRicanboy living in a medium-skinned curly-haired, RacialdistincAfricanAmericanneighborhood. primarily and of historyandlegal mechanisms tions arethe products do not confollll to scientificallyvalidbiologicalor genetic PuertoRicanswith Africanancestryare a case categories;

andin their in point,bothin termsof officialdefinitions dailylives. is thatin depicting WhatCarloshas also pinpointed rousedthe Mattelhas inadvertently kindsof blackness, no interrais (of course) There of miscegenation.ll specter no Eurasian Barbie, or quadroon no mulatto cial Barbie, TigerWoods thatlikegolf sensation nora Barbie Barbie, black, as "Cablinasian"-caucasian, mightbe described butseveral. notof tworaces, andAsian- a mixture Indian he is, forwhat a name oncreating insistence Woods' Tiger of Shani, backgrounds of theracial description likeCarlos' of ourracial Asha,andNichelle,speaksto the inability of kids the finelytunedperceptions to capture categories how to putthe "one who maynotunderstand (oradults), when lives,especially everyday in their rule" to work drop of whoarethemselves of parents theymaybetheoffspring Racial identity,in other races or multiracial. different soexperientially, words,is complexand multifaceted worldof Mattel, In the made-up cially,andhistorically. thecurrent however, discourse, public American andmuch Black(not White, is to checktheboxesthatapply: option or Asian,NativeHawaiian ongin),Hispanic, of Hispanic Indianor AlaskaNative,or American PacificIslander,

Other.l2

in needof thekindof is deeply Barbie, Shani, likewhite in relation thathasbeengoingon foryears queering racial (1995),withherkeen Rand EvenErica gender. to Barbie's boundatheracial see a wayto queer eye,couldn't critical Why did it not Barbies. "White" and riesof her"Chicana" occurto her to switchthe dolls' heads?It says a lot of andexpeperception about minds andbodies, about things what thegirls form, thisis precisely and,in another rience, owndolls. weredoingwiththeir I knewin Newhallville Braids and the Blonde Doll sister Clance younger of Cherelle's I havea photograph nexttoheryounger porch, stepsof their onthefront sitting all of of six children, was thefourth Joey.Clarice brother Thefamily, mother. liketheir almost exactly whomlooked wasin frommeinNewhallville, thestreet wholivedacross theoldestsonwasinjail,writchaotic state: a simmenng thechilat home; to his sisters ing longandlonelyletters and habit; kicking a drug trouble washaving mother dren's spentmuchof hertimecarCherelle s oldersister Clarice' wouldoftentellme, Cherelle siblings. ingforheryounger all thekids raised "Idon'twantto haveno kids,I alleady Cherelle to slights, andsensitive I'm goin'to."Stubborn of in schoolandwasontheverge in fights hadbeengetting andkindmotherbutshewasalsoa patient beingexpelled sisterdownon thefront heryounger oftensitting sibling, and herhair,kissingboo-boos, stepsto greaseandbraid andJoey. withClarice games playing Joeyseemsto look out fromthe photo(at me) witha toy Heholdsa plastic glower. belligerent almost skeptical,

314

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST * VOL. 101, NO. 2

* JUNE 1999

Figure 3. Clariceand Joey on theirfront stoop. Clarice and her doll wear similarhair styles. Photo by ElizabethChin, 1992.

in his handas if to displayit to me, the way you mightdisplay a weapon.Clarice,more at ease, has a doll snuggled on her lap. Againstthe darkcolor of Clarice'sT-shirt,the doll's light skin and blondehair are blazinglywhite. The front section of the doll's long, silky hair is done up in braids,each held at the end with a small plastic barette. Like the doll, Claricehas her hair in braids,and like the doll, the end of each braidis securedwith a small plastic barette. The firstthingone mightnotice aboutClariceand her doll is thatClariceis black and her doll is white. But Clariceand her doll are also wearingtheirhair in almost identicalways. Several otherNewhallvillegirls had dolls that,while white,haddistinctly un-whitehairdos. When white baby dolls with cascades of long blonde hairhave thathairheavy with beadsandfoil, or tuckedup into a braid-upon-braid 'do, what has happenedto the boundary betweenwhiteandblack?One obviousdevelopment is a sort of appropriation: the image thatjumps to

mindis Bo Derekin the movie 10 jogging along a Canbbeanbeachin slow motion,herhairbraidedandbeaded,a vapid smile on her face, her sleek Barbie-dollbody the mainplot elementin the film. Derek'shairstylesparked a vociferouscriticismfrom the black communityfor being yet another instanceof white co-optation of blackcultural forms.The film also spawneda beach-sidecottageindustry in the Caribbean, where (native)women and children scourvacationspotspersistently tryingto recruit peopleto get theirhairbraidedas a sort of souvenir.In one surreal encounter, I came acrossa huddleof young, white Christian missionaries in the Port-au-Prince airport in Haiti,the womenwearingfuzzed-upcornrowsandsingingChristian hymns in Kreyol.Clearly,the cornrowshad hardlytransformedthesepeopleor theirbeliefs. The context in which heads get done matterstremendously, and what is happening betweenNewhallvillekids andtheirdolls is not directlyanalogousto whathappens to

CHIN /

ETHNICALLY CORRECT DOLLS

315

vacationers in St. Croix, to Bo Derek's haar, or to Amencanteenagers on a religious mission. Thesesituations are not analogous pnmarily because the powerrelationships andconceptual boundaries betweenwtliteandblackare destabilized as Newhallville girlsbraid their dolls'hair, in a waythattheyarenoton a Bajan beach. Thisdestabilizationis delicate, fleeting even,andis likelyto havelittlesocialimpact beyond therealm of thesechildren's ownpersonalspheres, because it is undertalcen in the contextof far-reaching andmultiple oppressions. What kidsaredoing withdollsis limited muchas I haveasserted thattheselfesteemangleis also limited.Suchdestabilization is not evenlikelyto haveanyrealorlasting impact onthesekids' livingrelationships witheiffier whitepeopleortheideaof whiteness: theelements of playandcontrol present in doll hairstyling aremarkedly missing in kids'interactions with theirwhiteteachers, shopkeepers, police.Though fleeting andprecarious, whatthese girlsare doingsubtlyworks awayattheconstricted andconstricting notions of racethat continue to dominate current discourse. It is a formof racial integration thathasbeenlargely unimagined by adult activists, scholars, politicians, ortoymanufacturers. Clarice doesnotappear to assume that justbecause her dollis white,shemust treat herthat way.When deciding to doherhair, shegivesherverywhite, veryblonde, andvery blue-eyed dolla hairstyle that is worn byyoung blackgirls. Shedoesnotputherdoll'shairintoa ponytail,orbrush it over and over againjust for the pleasure of feelingthe brush traveling the longstrands. Clarice was not alonein this:other girls'dollshadbeads in their hair, braids heldat theendwithtwistsof tinfoil,andseries of braids thatwere themselves braided together. Insomesense,by doingthis, thegirlsbring their dollsintotheir ownworlds, andwhitenesshereis notabsolutely defined by skinandhair, butby styleandwayof life.Thecomplexities of racial reference andracial politics havebeenmuch discussed in thecaseof blackhairsimulating the look of whiteness; whatthese girlsarecreating is quite theopposite: whitehair thatlooks black. The question of hairin African American culture is a particularly contentious one, especiallyfor girls and women.Hairemergesas an almostliving character in scoresof novels,memoirs, magazine articles, andscholarlyworksby or about African American women.l3 As a primary racial marker, hair hasbecome increasingly politicizedas a medium through which racial identity potentially maybe embraced or erased (Mercer 1990).Debates over whether blackwomenandgirlsshould do thingsto their hairthatmakeit approximate the straight, siLky, flowing hair associatedwith whitenesshave been especially heated. At an extreme, curly,nappy hairhasbeenjudged "bad" hair, whileflowing, silkyhair is "good" hair. Given thissituation it is nowonder thatDarlene PowellHopson encouraged Mattel toproduce dollsthat hada vari-

ety of hairtextures. However, because hairplayhas becomean increasingly central element of toy marketing to girls,Mattel did not comply. Eachof the Shanidollshas what kidsinNewhallville called"Barbie DollHair," styled in wayssimilar to thosetypical of white Barbie dolls:curls forNichelleandAshaanda crimped stylesimilar to that foundon "Totally HairBarbie" forShani. In a somewhat half-hearted stabat African-Americanizing this hair,my "Beach Dazzle" Shaxii dollscomenotwiththebrush that mywhite Barbie has,butwide-toothed implements that the company descrlbes as "hair picks." Asidefromfacialfeaturesandskintone,blackness seemsto be signified more by accessories thananything else, at leastin the hairdepartment, a development thatDuCilledescribes as "preciousready-to-ware difference" (1996:43). Thesegirls'workon their dolls'heads, however, makes it seemas if thegoodhair/bad hairdebate is notso simple as nappy versussilky,blackversuswhite.AmongNewhallville children, andamongmy ownAfrican Amerlcan students at the collegewhereI teach,the phrase "Barbie Doll Hair" denotesa specificphenomenon-long, long silkyhair. There areatleastthree typesof Barbie DollHair that kidsreferred to whentheyusedthisterm: (1) thekind thatgrowsout of the headsof "white" girls,(2) thekind implanted totheheadof a Barbie Doll,and(3)thekindyou buyata beauty shopandaddonto yourown.Theproblem is complex: whenpurchased Barbie Doll Hairis usedin distinctively black hairstyles, it is notjustanexercise in reproducing whiteness uponblackgirls'heads. Whileactual White GirlHairmight be appropriate forusein stylesthat do replicate theheadof whiteness, it doesnotserveat all fora wholerange of other stylesforwhichsynthetic hairis perfect. Somecall for melting the endsof synthetic hair, whichwould be a disaster withWhite GirlHair, yielding a lot of stink,butno fusion.Whilesynthetic hairmaybe metaphorically white,it literally is Barbie DollHair: both are madefromthe same material knownas Kanekalon (Jones1990:290). Thenow-common jokeis whensomeone asksyou if that's"your hair" to respond, "Sure it's mine.I bought it!"Thisreference alludes notonlyto plain oldracebutto goodoldconsumerism, andelidestheabsolutedifference between whatis whiteandwhatis black. Ultimately, it may be the reference to consumerism that maybe moreimportant forthe girlsandwomensporting Barbie DollHair ontheir heads. Canonereasonably argue, in thefaceof thatkindof statement, thatthebraid-ins, extensions, orweaves are"really" whiterather than black?l4 Accepting stereotypical notions about black hairmakes light of the fact thatthe "good" and "bad" hairdebate wouldnotbe possible if blackkidsdidnothavehairthat comesnotjustin tight,nappy curls, butalsoin straight or curly locksas siLky, andevenasblonde asVeronica Lake's famous eye-obscuring cascade. There aresomeindications thattheabsolute linebetween whatconstitutes "black" or

316

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST *

VOL. 101, NO. 2

* JUNE 1999

Figure 4. LaQuishaand her CabbagePatchKid. Photo by ElizabethChin, 1992.

"white" hair was originally enforced by whites who of theirracialidentity: hairas a marker claimedlong siLky there are accountsof slave-owningwomen, who, when faced with female slaves who had long, silky hair, would remove the offendingtressesfrom the slave's head to enforce theirblackness(WhiteandWhite 1995).15 Underlyingcriticismsof Barbie Doll Hair is the assumptionthat white hair must be treatedwithin the conIf one it is seen to represent. fines of the racialboundaries acceptsthatracialdivisionsareabsoluteandunbridgeable, what these girls are doing with their dolls makes little on a white doll? And yet, sense. Why put a blackhairstyle if these dolls belong to these black girls, and live in the worlds they inhabit,how inflexibly white are they? Reon Barbie,which memberAsia and Natalia'sruminations betweenthem urgentlypointedoutthatthemaindifference with a nod to race,but and the doll could be summarized really rested on the way they lived, the way they spoke.

These criticismsapplyas muchto Shanias they do to any otherwhite dolls. Whatthese girls are doing seems to reof nature cognize in multipleways the sociallyconstructed existence,andthe flexiof a racialized race,the ambiguity it is not always or only the bility of racializedexpression: color of their dolls that makes them hardto relate to or whatthesegirlsaredoingemphaidentifywith.Moreover, sizes thatthey do not needto buy racialdifference,or even to buy dolls thatlook like them;they can createdolls that ways throughtheir own look like them in fundamental work. andmaterial imaginative as absolute The girls' refisal to acceptracialboundaries with spilled over into my relationships and unbridgeable fascinated were they them, since from the very beginning As I grewto Doll Hair." "Barbie withmy own waist-length know the girls better,they beganto get theirhandsin my hair,styling it in ways thatmade me look betterto them, to me boi physically nearness their whilealsodemonstrating

CHIN /

DOLLS CORRECT ETHNICALLY

317

bunsandmessy Rather thanmypractical andemotionally. my hairintosleek gel and twist yankand they'd ponytails, of eachear, curls justin front withlong,twirling topknots eachone. andbraid myhair intofiveorsix sections orpart spentfive hoursmeticuNyzerraye Onerainyafternoon, theirends my hairinto over sixty braids, louslyputting sealedclosedwith bits of Reynold'sWrapthatmadea Thesegirls myhead. sound whenI shook musical scratchy, ondayslikethis,andwhen myheadaround werechanging andsentme intothebaththeircreations they'dfinished roomto lookat theirwork,it seemedthatit wasn'tquite wasnotto Their workof transformation me in themirror. my raceor racialidentityin some biological rearrange to makeme more theywereworking sense;nevertheless, joy in bejustas theydidwiththeirdolls.Their likethem theweek and during tangible, me was ing ableto re-create me withsurprised stayedin kids greeted thatmy braids You MissChin,you got yourhairbraided! glee:"Ooooh, lookso nice!"

of inthepersonality doll,andomissions in a ShaIii ancestry not"dope." as "nice," bedescribed whomust Barbie about Barbie girlssaidandthought WhatNewhallville a socorrect dollsmaynotprovide ethnically that indicates in thesetoys,whichadembodied lutionto theproblems the diversifying butlittleelse.While theissueof race, dress andTarget, atToys'R' Us, Walmart, mixavailable ethnic do notredefine producers dollsandtheir correct ethnically of color to children accessible itselfas a sphere themarket best intenwho are also poor:despiteany corporation's dollssold Kenya anyof the500,000 that tions,it is unlikely kids'homes. by Tyco in 1992endedup in Newhallville be a democratic The notionthatthe toy box is or should theconsumer that heldnotion thecommonly spacemirrors of equal democratica placeandsphere is similarly world Makers to spend. witha fewbucks foranyone opportunity thisnotion correct dollsdolittleto discourage of ethnically insteadthe emphasizing marketplace, of the democratic of thebuyas part consumers of minority power growing of minortheentry children, Forpoorminority ingpublic. Conclusion hasmadelittle,if intotheindustxy ity toysandtoymakers orforthatmatter, ontheir owntoycollections, any,impact andsucitselfto wage a dramatic Oursocietycanmobilize self-esteem. their andits effectsuponhuracialprejudice cessfulwaragainst do kidslikethosein Newhallville because It is perhaps where the situation manbeings.In doingso it will eliminate beingmartobuythecommodities ability nothavea ready are the ones who have higher individuals the prejudiced boundaries ketedto themthattheyareableto bendracial to their status,and wherethey compelothersto conform middlewonders whether and one they do, readily as as (1955)1963:139] [Clark prejudices. ethlikelyto possess whoaremore children, classminority the kindsof critical fashioning dolls, are correct nically to the pioneering references consistent Whilemaking here.FromCabbage like thosediscussed their"dollstudies," commentaries andin particular workof the Clarks, beads andfoil to longheavy with with hair Kids Patch different a fundamentally dollsembody correct ethnically braided'dos, elaborately dolls sporting blonde haired The Clark envisioned. thantheone Kenneth socialproject not over again, over and were, Newhallville dolls in white in theformof effinidiversity racial effortto manufacture of course, still white, They were as such. recognized quite dollsis notin the endan effortto transform callycorrect of thedollsdidnot discourse. andkidsknewthat,butthewhiteness racial andbeliefsthatdominate theassumptions andgirls their worlds, them into integrating by YvonneRubie, stopgirlsfrom this comment for instance, Consider, to treatthemin waysthatcomdid not seemcompelled "If BlackToy Association: of the International president Andyet,I have of racial difference. boundaries memorate they thatarelikethemselves, growupwiththings children probably fleetare transformations that these noted already themselves orat leastidentify will tendto likethemselves who children of the consciousness even in the at best, ing, Ms. Rubie's (Ebony1993:66). withthatpositiveimage" "weak power," calls Fiske (1993) This is what them. create with things relationships that it is children's assertion of potential the transformative thatrecogIiizes a concept fortheir important thatis mostcritically than people rather Newhallby these undertaken those being like processes in linewitha andyetutterly startling, senseof selfis utterly the wiffiin potential butthatalsoplacesffiat villechildren, fitsin wellwiththe ethic.Thisunderstanding consumerist society within of the structure oppressive, and larger, the thingskids readyto supply of an industry emergence aregenerated. theseprocesses which butneatly self image" to havea "positive needin order by toy makof raceevidenced Therigidunderstanding and social,political, of findamental thequestion sidesteps anatof thefixityof genetics, experi- ers is one basedin notions issuesthatalso impingeon children's historical to reon its headbutnot an attempt temptto turnracism as people of themselves perceptions encesandhencetheir of ethnically imaginerace itself. Toy makershave remoldedtheir of makers in the world.Thisshiftis typical ultimately of thedebate, butnottheparameters products, arebeliedby whatcan toys,buttheseassumptions correct at least, a visionof racethatanthropologists, perpetuating children fromplaceslikeNewamong be seenandheard since the time of to dismantle have been endeavoring Asia, andNataliaarekeenly hallville.Kidslike Carlos, the marketas an exclusionary of race,seeingNativeAmerican Boas.l6In confronting of thecomplexity aware

318

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST * VOL. 101, NO 2 * JUNE1999

sphere, describing Barbieas 'snice," andthenwondertng why thereis no abusedor pregnant Barbie,Asia and Nataliarejectthe notionthat their self-esteem can be boosted through consumer itemsthat address issuesof race but neglectotherpressing issues.k making theirwhite dolls live in blackworlds,they similarly reconfigure the boundanes of race,whichminority toy makers portray as beingimmutable. In so doing,thesegirlschallenge thesocial construction not only of theirown blackness, butof raceitselfas well. Notes

Acknowledgments. I thankArlene Davila, Robert Gardner, MaureenO'Dougherty, and Mary Weismantel for their keen remarks and prodding questions. Faye Harrison, Helen Schwartzman, and an anonymousreviewerhelped to keep this work ethnographically centeredand providedthoughtful,generous remarks.Portionsof this paperwere presentedin an earlier version at the 1995 Annual Meeting of the AmericanAnthropologicalAssociation, Washington,D.C. The researchfor this paper was supportedby the National Science Foundation and the Wenner-GrenFoundation for Anthropological Research. My special thanks go to Kenneth Clark for granting me the Kennethand Mamie Phipps Clarkresearchfellowship in 1991. Most of all, I must thankthe many Newhallville children and their families who have so graciously let me into their lives since 1991. My careeris as much theirdoing as my own. 1. See Brewer (1997), Espiritu (1994), Harrison (1995). For an ethnographicstudy along these lines with youth, see Reynolds' (1995) work among Sikh youth in GreatBritain. 2. See Kinder (1991), McLaren and Morris (1997), and Seiter (1993). These works, which are theoreticallyinsightful with regardto toys, do not deal in depthwith issues of theorizing childrenand childhood. These authorsdo make efforts to discuss race and class. However, each author's analysis is hamperedby a problematictendency to rely on anecdotalevidence gatheredfrom their own (middle-class,white) children. Minority children are discussed, but not consulted, interviewed, or observed. This approach creates a hierarchy wherein middle-class white children are real and individual, while minoritychildrenare merely theoreticalandgeneric. 3. Some exceptions are Hill (1992) and McLoyd (1982, 1983). 4. See DuCille (1996), Lord (1994), Rand(1995). 5. "HulaHair Barbie"has flat feet, apparentlyso that she can swivel her hips, thoughthe box warnsthat"Barbiecannot Hula alone." Analysis of the racial implications of this doll-which are nearly irresistible in their ridiculousnessmust await anothervenue. 6. See Caputo (1995), Schwartzman (1978), Stephens (1995), Thorne(1987). 7. Bourgois has also documentedsimilarly early concerns among PuertoRicansin New York's East Harlem.One boy he knew "told us he hoped his mother would give birthto a boy 'becausegirls are too easy to rape' " (1995:213). 8. The studies have provoked a large and still growing literature that has challenged the original research (Burnett

1995), arguedfor recognizingthe importanceof social history and gender (Fine and Bowers 1984), and examinedcross-culturalvalidity problems(Gopaul-McNichol1995). The Clarks' original ideas about self-hatredand self-rejectioncame under special criticism in the 1970s and 1980s (Banks 1976; McAdoo 1985; Porter and Washington 1979). It was the Clarks' own assessment that other methods they had used were moreeffective in exploringthe complexitiesof children's racial identification(Clarkand Clark 1940, 1950), and yet the doll studiesremainfor the public the most compellingdemonstrationof the negative effects of racism on black children's self-conceptor whatis moreoften now called self-esteem. 9. It is a testamentto the emotional power of the doll studies that it is often assertedthese very studies were responsible for convincing the Supreme Court justices that segregated schools caused unconscionable damage to black children (McAdoo 1985; Wallace 1990; Wilkinson 1979). Neither the doll studiesnorpsychologicalresearchby KennethClarkwere mentionedin the text or footnotes of the court's decision. The famous referencein footnote 11 of the court's decision refers not to the doll studies,but to an overview of the social science literature assessing the impact of segregation on children. KennethClarkhad preparedthis summaryreportearlierfor a nationalsummiton youth. His own studies are mentioned,but the majorityof the work reviews a variety of studies focused on children from a variety of ethnic groups, races, and cultures. Among the materialspresented to the SupremeCourt was an Amicus Brief detailing the social effects of enforced segregationsigned by 33 social scientists, including Kenneth Clark. 10. Urla and Swedlund(1995) did find physicaldifferences in an anthropometric comparisonof Barbie and Shani, but because theirmeasurements were recalculatedon the assumption that Barbie is 5'10", the absolute difference in the two dolls' sizes was not provided. None of these changes, DuCille (1996) notes, preventthe Shani dolls from being able to wear Barbieclothes. With Barbiesetting the standard for the 11-1/2 inch fashion doll, Olmec's Imani doll also can wear Barbie's clothes, and this is mentionedon the front of Imani'spackage. Even the newly redesignedBarbiebody, toutedat the 1998 InternationalToy Fair as being more representativeof something approaching a living humanfemale, appearsto be able to wearthe old Barbieclothes. 11. DuCille (1996) writes that Colored Franciealso raised the issue of miscegenation,since she was the black version of Barbie's cousin Francie.This is entirely possible, but there is little direct evidence that childrenor other consumersreacted this way to the doll. 12. In 1997 the Federal Government,after four years of contentiousdebate, decided to allow people to use more than one racial category when identifying themselves. For the first time, the estimated 2,000,000 mixed-race Americans will be able to approximatesomething like Woods' "Cablinasian" status when filling out census forms. The notion of separate races, however, remainsunchangedin this new policy (New York Times 1997). 13. See DuCille (1996), Morrison(1970), Rooks (1996). 14. The black/whitedistinctionabout this hair is probably inappropriate in any case. Most humanhairsold to the African

CHIN /

CORRECT DOLLS ETHNICALLY

319

American market comes from Asian countries, primarily China,India,and Thailand(Jones 1990). 15. Kobena Mercer's observationthat no black hairstyleis (Mercer 1990) applies equally to white inherently "natural" hair.White Girl Hair, especially in the long and flowing form represented by Barbie,can be difficult to maintain.In the long and flowing version, this kind of hair is no more a naturalor easy assertionof whiteness thanthe Afro or Dreadlocksare an easy or naturalassertion of blackness. In any case, the tradition of long flowing hair is much more prevalentamong Chicanas and Asians thanit is among whites. 16. Lee D. Baker's work (1992) on this subject amply documents that this enterprisehas been rife with complexity and contradictionand is historicallynot as rosy as many of us institutions! were taughteven in left-leaninggraduate

References Cited

Abu-Lughod, Lila TracingTransformations 1990 The Romanceof Resistance: of Power throughBedouinWomen. AmencanEthnologist 17(1):41-55. Aries, Philipe 1962 Centuriesof Childhood:A Social History of Family Life. New York:VintageBooks. Baker, Lee David 1992 The Role of Anthropologyin the Social Construction Anthropology Deof Race, 1896-1954. Ph.D. dissertation, partment, TempleUniversity. Banks, W. C. in Searchof a in Blacks:A Paradigm 1976 WhitePreference PsychologicalBulletin83(b):1179-1186. Phenomenon. Bateson, Gregory In StepsTowards [1955]1972 A Theoryof PlayandFantasy. andScranan Ecology of Mind.Pp.177-193. SanFrancisco ton:Chandler. Bourgois, Philippe Univer1995 In Searchof Respect.New York:Cambridge sity Press. Brewer, Rose M. The New Schol1997 TheorizingRace, Class, and Gender: and Black Women's arshipor Black FeministIntellectuals Feminism:A Readerin Class, DifferLabor.In Materialist ence, and Women's Lives. RosemaryHennesy and Chrys Ingraham, eds. Pp. 23S247. New York:Routledge. Brown, Michael F. 1996 On Resisting Resistance. American Anthropologist 98(4):729-735. Burnett,Myra N. A Questionof Validity.Journal 1995 Doll StudiesRevisited: of BlackPsychology21(1):19-29. Caldera,Yvonne M., Aletha C. Huston,and MarionO'Brien and Play Patternsof Parentsand 1989 Social Interactions Toddlers with Feminine, Masculine, and Neutral Toys. ChildDevelopment60:7S76. Caputo, Virginia 1995 Anthropology'sSilent 'Others':A Considerationof Issues for the Study Some ConceptualandMethodological of Youth and Children'sCultures.ln Youth Cultures:A

Perspective.Vered Amit-Talaiand Helena Cross-Cultural Wulff,eds. Pp.1942. New York:Routledge. Chin, Elizabeth and Social Experience 1996 FetteredDesire: Consumption among Minority Children in New Haven, Connecticut. Ph.D. dissertation,Anthropology Department,Graduate Schoolof the City Universityof New York. 1998 Social Inequalityand Servicescape:Local Groceries In ServandDowntownStoresin New Haven,Connecticut. Markets. icescapes:The Conceptof Place in Contemporary Jr.,ed. Pp.591-617. Chicago:NTC Group. JohnF. Sherry, Clark, Kenneth B. Boston: BeaconPress. andYourChild. [1955]1963 Prejudice Clark, Kenneth B., and Mamie K. Clark 1939 The Developmentof Consciousnessof Self and the Emergence of Racial Identificationin Negro Preschool Children.Journalof Social Psychology, SPSSI Bulletin

10:591-599.

of Negro 1940 SkinColoras a Factorin RacialIdentification Social Psychology, SPSSI Children. Journal of Preschool Bulletin11:159-169. Clark, Kenneth B., and Mamie Phipps Clark 1947 Racial Identificationand Preferencein Negro Children.In Readingsin Social Psychology. T. M. Newcomb eds. Pp.169-178. New York:HenryHolt. andE. L. Hartley, andPrefer1950 EmotionalFactorsin RacialIdentification ence in Negro Children. Journal of Negro Education 19(3):341-350. Cross, Gary 1997 Kids' Stuff:Toys and the ChangingWorldof AmeriUniversity Press. Cambridge, MA: Harvard canChildhood. DuCille, Ann University Press. Cambridge, MA:Harvard 1996 SkinTrade. Ebony 1993 New Boom in EthnicToys: ExpertsSay the Trendis 64 66. MorethanSkinDeep. Ebony,November: Erikson, Erik New York: Norton. andSociety.2ndedition. 1964 Childhood Espiritu,Yen Le 1994 The Intersectionof Race, Ethnicity,and Class: The Filipinos.IdentiMultipleIdentitiesof Second-Generation ties 1(2-3):249-273. Fine, Michelle, and Cheryl Bowers The Effects of Social His1984 Racial Self-Identification: tory and Gender. Journalof Applied Social Psychology 14(2):13S146. Fiske, John 1993 Power Plays, Power Works. Londonand New York: Verso. Miriam Formanek-Brunell, 1993 Madeto PlayHouse:Dolls andtheCommercialization of AmericanGirlhood,183S1930. New Haven,CT: Yale UniversityPress. Gopaul-McNichol,Sharon-Ann of Racial Identityand Examination 1995 A Cross-Cultural in the West Indies. of PreschoolChildren RacialPreference Psychology26(2):141-152. Journal of Cross-Cultural

320

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST * VOL. 101, NO. 2

JUNE 1999

Harrison,Faye V. 1995 The Persistent Powerof "Race" in the Cultural andPolitical Economy of Racism.AnnualReview of Anthropology 24:47-74. Henry, Jules, and Zunia Henry 1974 Doll Play of Pilaga IndianChildren.New York:VintageBooks. Hill, Ronald Paul 1992 Homeless Children:Coping with Material Losses. Journal of Consumer Affairs26(2):274-287. Jones, Lisa 1990 Bulletproof Diva. New York:Doubleday. Kelly-Byrne, Diana 1989 A Child's Play Life: An Ethnographic Study. New York:Teacher'sCollege Press. Kinder, Marsha 1991 Playingwith Powerin Movies, Television,andVideo Games:FromMuppetBabiesto TeenageMutant NinjaTurtles. Berkeley:Universityof California Press. Lord, M. G. 1994 ForeverBarbie: TheUnauthorized Biography of a Real Doll. New York:WilliamMorrow. McAdoo, HarriettePipes 1985 Racial Attitudeand Self-Conceptof Black Children OverTime. In Black Children: Social,Educational, andParental Environments.HarriettePipes McAdoo and John Lewis McAdoo,eds. Pp.213-242. London:SAGE. McLaren, Peter, and Janet Morris 1997 Mighty MorphinPower Rangers:The Aesthetics of Phallo-Militaristic Justice.In Kinderculture: The Corporate Construction of Childhood.ShirleyR. SteinbergandJoe L. Kincheloe, eds.Pp.115-128. Boulder, CO:WestviewPress. McLoyd, V. 1982 Social Class Differences in SociodramaticPlay: A CriticalReview. Developmental Review 2:1-30. 1983 TheEffectsof the Structure of PlayObjectson the Pretend Play of Low-Income Children.Child Development 54:626-635. Mercer, Kobena 1990 Black Hair/StylePolitics.In Out There:Marginalization in Contemporary Cultures.Russell Ferguson,Martha Gever, Trinh T. Minh-ha, and Cornel West, eds. Pp. 247-264. New YorkandCambridge, MA: New Museumof Contemporary ArtandMITPress. Miller, Daniel J. 1995 Consumptionand Commodities.Annual Reviews in Anthropology 24:141-162. Montessori, Maria [1912]1964 TheMontessori Method.New York:Schocken. Morrison,Toni 1970 TheBluestEye.New York: Holt,Rinehart andWinston. New York Times 1997 Multiracial Americans. Editorial, November8: A14. Pellegrini, Anthony D., and Ithel Jones 1994 Play, Toys, and Language.ln Toys, Play, and Child Development. Jeffrey H. Goldstein,ed. Pp. 2745. New York:Cambridge UniversityPress.

Porter,J., and R. Washington 1979 Black Identityand Self Esteem:A Review of Studies of Black Self-Concept. Annual Review of Sociology 5: 53-54. Powell-Hopson, Darlene 1985 The Effects of Modeling, Reinforcement, and Color MeaningWord Associationson Doll Color Preferences of Black PreschoolChildrenand White PreschoolChildren. Ph.D.dissertation, HofstraUniversity. Rand, Erica 1995 Barbie'sQueerAccessories.Durham, NC: Duke UniversityPress. Reguero, Wilfred, and Marilyn Crane 1994 ProjectMotherCare: One Hospital'sResponse to the HighPerinatal DeathRatein New Haven,CT.PublicHealth Reports109(5):647-652. Reynolds, Pamela 1995 Youth and the Politics of Culturein South Africa.In Childrenand the Politics of Culture.SharonStephens,ed. Pp.21S240. Princeton, NJ:Princeton University Press. Rooks, Noliwe M. 1996 HairRaising:Beauty,Culture,and AfricanAmerican Women.New Brunswick, NJ:Rutgers University Press. Schwartzman,Helen B., ed. 1978 Transformations: The Anthropology of Children's Play.New York:Plenum. Seiter, Ellen 1993 Sold Separately:Childrenand Parentsin Consumer Culture. New Brunswick, NJ:Rutgers University Press. Sholle, David 1990 Resistance:Pinning Down a WanderingConcept in CulturalStudies Discourse.Journalof Urbanand Cultural Studies1(1):87-105. Stephens, Sharon 1995 Childrenand the Politics of Culturein "LateCapitalism." In Children and the Politics of Culture. Sharon Stephens,ed. Pp.348. Princeton, NJ:Princeton University Press. Sutton-Smith,Brian 1986 Toys as Culture. New York:Gardener. Thorne, Barrie 1987 Re-VisioningWomen and Social Change:WhereAre the Children? Gender& Society 1(1):85-109. Urla, Jacqueline,and Alan C. Swedlund 1995 The Anthropometry of Barbie:UnsettlingIdealsof the Feminine Body in Popular Culture.In Deviant Bodies: CriticalPerspectiveson Differencein Science and Popular Culture. Jennifer Terry and Jaqueline Urla, eds. Pp. 277-313. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. U.S. Bureau of the Census 1980 Censusof Populationand Housing.Washington, DC: GovemmentPrinting Office. Wade, Peter 1993 'Race',NatureandCulture. Man28:17-34. Wallace, Michele 1990 Modernism,Postmodernism and the Problemof the Visualin Afro-American Culture. In OutThere:Marginalization and ContemporaryCultures. Russell Ferguson, Martha Gever,TrinhT. Minh-ha,andCornelWest,eds. Pp.

Refections otG;ay and-Lesbian Anthropotogists ::00

00

:00-;

0;

CHIN I ETHNICALLY CORRECT DOLLS

321

39-50. New YorkandCambridge, MA:New Museum of ContemporaIy ArtandMIT Press. White,Shane,andGraham White 1995 SlaveHair andAfncan American Culture in theEight eenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Joumal of Southern History 61(1):45-76.

Wilkinson, J. Harvie,III 1979 From Brown toBakke: TheSupreme Court andSchool Integration: 195F1978. NewYork: Oxford University Press. Williams,Brackette 1995 Beaming ThemUp:FirstBloodandSomeViewson thePleasures andDangers of Fresh Bloodin theMaking of U.S.Americans. Identities 1(4):427-442.

:ff f ;fi: f! f ;Df :::: :E: ;; f:

SEX,SIX4UAIITY, AND THE :X: SSS :; :: ANTHROP0OLOGIST ;f:f0000:0000 :000000

EDITED BYFRAN400 MARKOWITZ AND MICHAEL ASHKENAZI: CE S

f iT f jE. . i. if f ;;

"A balanced

and $frich-00;collection."

William

Leap, coeditor0-of

Out in00 the Field:

. . A significant

T. f

;:j50

0 fX f idS:00000

itt?:;0:X00.::X-X;000::ji f:X)j:ff:

"Help[s]

reAl;ore some-sanity

* i fi

to our erotophobic author of

American

cultue.0-.

f ffiS .ifE f

contribution0."

WaCterXWilliams,

inAmerican tndian Cultbre:

TheSpirit and the Fle. Saual Diversity t000 - ;y

W

l0

h:::1

: |

CIOthS $34.95;PaPer,:$ I8.95

X;000:fS ;000: $0: 0;

INDIANCOU5NTRY, L.A.

000-

00 ;0-XS:::f0004

--

t0:

f: Q

Maintaibing Ethnic000fCommunity in Complex Society

JOAN WEIEBEL-ORLANDO

t:;0: f:f: ; ::

Revised Edition 0:0):

::0:

'sAn invaluable

:

resource

for anyone

interested

in contemporary

Native Americans."

Choice 0: ff0

f: : ::

:0:: f;

a classic in both Indian and urban studies" Joan Ablon,

'sShould author Illus.

surelysfbec:ome of

Living t&thf Difference

$55.00; Paper,

j ;S

Cloth,

$19.95

Photo by RobertA. Orlando

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Wolfe, Cary - ZoontologiesDocumento114 pagineWolfe, Cary - ZoontologiesAlejandro Cabrera Hernández100% (2)

- Power Dolls ManualDocumento45 paginePower Dolls Manualgideon020100% (2)

- Fragmented Female Body and IdentityDocumento23 pagineFragmented Female Body and IdentityTatjana BarthesNessuna valutazione finora

- Australian Art: Alex KuskowskiDocumento34 pagineAustralian Art: Alex KuskowskiDương Nguyên XuânNessuna valutazione finora

- Old Rosshire Scotland 1530-1800Documento494 pagineOld Rosshire Scotland 1530-1800PAUL KAY FOSTER MACKENZIE100% (1)

- Inalienable PossessionsDocumento263 pagineInalienable PossessionsFlávia Penélope100% (1)

- Annette B. Weiner-Inalienable Possessions - The Paradox of Keeping-While Giving-University of California Press (1992) PDFDocumento263 pagineAnnette B. Weiner-Inalienable Possessions - The Paradox of Keeping-While Giving-University of California Press (1992) PDFCristiano Desconsi100% (2)

- Traditionalist Confronts Fascism Julius EvolaDocumento3 pagineTraditionalist Confronts Fascism Julius EvolaVirgilio de Carvalho0% (1)

- "I Have A Dream" EssayDocumento4 pagine"I Have A Dream" EssayMia M.Nessuna valutazione finora