Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Stella Joy, Part III: The Final Days

Caricato da

Toronto StarTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Stella Joy, Part III: The Final Days

Caricato da

Toronto StarCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A6TORONTO STAR MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2012

ON ON0

> >

STELLAS STORY

TARA WALTON/TORONTO STAR

Stella Joy, Part III

Final days

Now 3, Stella has created a dance pattern with death 10 steps toward its dark shadow, then a hop back into the light. Yet as the hot summer rolls into fall, she is getting thinner and thinner . . .

Stella Joy Bruner-Methven was told she had days left to live. Sure enough, she bounced back. The 3-year-old never met a rule she didnt take pleasure in breaking. Nine days after she stopped eating and drinking anything but ice chips, she awoke, opened her eyes wide and clear and demanded some breakfast. Since she could no longer speak, she did that by sticking out her tongue. She then proceeded to eat two bowls of porridge, a generous helping of her 11-month-old brother Sams apple sauce, some chocolate Timbits her grandfather Poppa brought over, two bottles of milk . . . Stella is just eating some macaroni and cheese, dont mind her, her mother Aimee Bruner says as Dr. Pawandeep Brar enters their East York house. Brar is Stellas palliative care doctor. Ten days ago, she warned Stellas mothers their daughter Stella had days left. But here she is, sitting on Aimees lap on her favourite couch, digging into her second bowl of macaroni and cheese. Her ginger hair has been pulled into two little pigtails. Her fingernails are purple. She is wearing a red Super Girl T-shirt. Her eyes are still wide and alert. She opens her mouth, and over seconds, so faintly you have to lean in to hear, breathes the word Mom . . . ma. Were hardly ever wrong about this, Im not going to lie, Brar says. Im very surprised. A year and three months ago, Stella was diagnosed with diffuse infiltrative pontine glioma (DIPG) a rare brain tumour that kills its child victims after torturing them by slowly and methodically cutting their brains command over each of its functions. DIPG buries its victims in their stony bodies while keeping their brains alert, so they can watch it happen. There is no cure. Most parents agree to six weeks of radiation to hopefully delay the tumours advance and grant their child what doctors grimly call a honeymoon period. Stellas two mothers, Aimee and Mishi Methven opted against that. They didnt want any of their daughters precious remaining time spent in hospital. Doctors expected Stella to live three months. Yet here she is, back from the brink yet again. Her family called off the vigil, packed up the trays of sandwiches and bouquets crowding their kitchen counters, asked a friend to hold off building another wooden casket to fit Stellas lengthened body (she has grown 10 inches since she was diagnosed), and stepped back out into the warmth of September with their beautiful, funny child. Over the past week, our girl has played in the sandbox and the backyard plastic pool. Shes had her face painted at a nearby farmers market and rode on her mothers laps on the swings. This morning, she wiggled her torso in delight at the sight of the elevator doors opening and closing at the library. Her mothers bought a new minivan using some of the $65,000 friends and strangers have donated to the family since Stellas diagnosis for a down payment to fit all three of their kids, and planned their fourth trip to Great Wolf Lodge. Stella clearly has some living left to do. Brar stares quizzically at Stella. This has been the 3-year-olds dance pattern with death 10 steps toward its dark shadow, then a hop back into the light. As it grows in the brain stem, the tumour blocks the flow of cerebral-spinal fluid. This causes pressure on the brain, called hydrocephalus. Brar figures this is the cause of Stellas coma-like states. Then there is a shift, and the pressure is relieved. But the tumour is still growing. There is no doubt of that. And eventually, it will cut the command to Stellas heartbeat or breath. DIPG has a 100-per-cent mortality rate. Eventually it kills all of its young victims. Stella wont be different. But that could be months away. Glorious months. As Brar says her goodbyes, Stella finishes her third bowl of macaroni and sticks out her tongue. Translation: one more bowl please. IT IS A GREY, warm day in mid-October. The green leaves of the flowering crabapple tree outside the familys bungalow show a tint of yellow. Step inside, and the first thing youll

CATHERINE PORTER

ONE LITTLE GIRL, ONE BIG STORY

Over the course of a year, Stellas family, friends and complete strangers worked to give the ailing toddler a lifetime of experience. Star journalist Catherine Porter was there every remarkable step. Her three-part chronicle of Stellas journey appeared Saturday through today. The full series is available at thestar.com

notice is Stellas absence. Her favourite living room couch is empty. Our girl is lying in the middle of her mothers king-size bed, between Mommy Aimee and Auntie Andrea Bruner, whom everyone calls Andgie. Stellas ginger hair glimmers softly on the white pillow. Her face is calm and ivory-coloured. Her eyes are halfclosed. The room echoes with the rhythmic sound of her sucking her tongue, clicking like a metronome. Her most recent honeymoon lasted a delicious one and a half months. But its over now. Its been five days since she ate or drank anything. The ice chips her aunties slip into her mouth mostly dribble out. She hasnt woken up for two days. I cant believe this is my baby girl, Aimee says, holding Stellas hand. It is long and misshapen, knuckles curled like a grandmothers after years of arthritis. We are sad for you, baby girl, Auntie Andgie says softly from her other side. Im sad for us, says Aimee. The family is back in vigil mode. They take turns lying beside Stella, holding her hands, whispering their love to her. She is never alone. Close family friend and childrens bereavement counsellor Andrea Warnick has advised Aimee and Mishi to tell Stella its all right for her to leave. That they will be OK without her. Kids have the same protective instinct for their parents as parents do for their kids, says Warnick. Stella might not be holding on out of stubbornness, but concern for her mothers. I told her, Its OK to go, says Aimee, but Mishi is not ready to do that yet. Its the final act of parenting sacrificing your own heart again to give solace to your child. The truth is, no one is ready for Stella to leave. Theyve had a year more than promised since her diagnosis and, every moment has been precious. But it will never be enough. We are going to be so lost, Mishi says, coming into the room with her sister, Heather. Weve spent so long being her moms, what will we do all day? she continues, nuzzling Stellas neck. What will we ever do that is as meaningful as this? SINCE THAT WRETCHED night at the Hospital for Sick Children when Aimee and Mishi first heard the acronym DIPG and their bright shiny world shattered, theyve said they wanted Stella to have a good death. Its an obscene term theyve learned from their friend Warnick. What does it mean? For a start, it means no pain. No physical pain and, more important, no psychological pain. Thats why palliative doctors like Brar talk to their patients about legacy, as well as morphine. Most of us want to settle things before we go. For some, that means finishing that doctoral thesis, Brar says. For others, its writing a reflective essay about their life or spending those last days with their far-flung loved ones. Its also about resolving the fear of

During the more than a year that Stella has been living with a terminal brain tumour, she has outgrown the original pine coffin a family friend built for her tiny body. In late August, Auntie Andgie measures her lean frame so a new coffin can be built.

being forgotten, Warnick says. Unlike Africa or Central America, we North Americans do a lousy job of remembering our dead. That has deep implications. For parents of kids dying, that translates into, Are people going to forget my child? she says. Are they never going to bring up his or her name? Theres a saying, Mentioning my childs name may make me cry, not mentioning my childs name will break my heart. Stellas family has prepared her legacy. Theyve ordered 500 metal stars with her name on them. Stella is Latin for star, and since her diagnosis her mothers have thought of her as a shooting star. They want her friends to leave the Stella stars in places their daughter never got to see, so through them shell continue to grow. Already, the female directors at the Mount Pleasant Visitation Centre, where Stellas funeral will take place, have left Stella stars in China and Floridas Disney World. Their friends have planted a tulip tree in her honour outside the gates of her favourite place in the world, Riverdale Farm. A bench will soon go next to it with her name. Every Christmas Eve, her family plans to decorate that tree. And they will light a candle for Stella every single day in April, the month of her birthday. Stella will always be part of the family, Warnick says. The last thing left is to make a death plan, similar to a birth plan. They cant control when Stella goes, but they can make sure she isnt in pain and is surrounded by her loving family. Her mothers want to hold her alone for her last breath. STELLA IS SLOWLY disintegrating before our eyes. Her rib cage protrudes, her once-chubby belly sinks. When Mishi lifts up her loose red sweatpants to prepare for a new morphine injection site, she reveals a stick-thin thigh. Her sunken eyes are red. Our poor, beautiful girl is dying from a brain tumour. But she looks like she is starving to death. Mishi has to be reminded of this, time and time again. Eating less is a symptom of her dying, not the cause, Brar repeats. If we force people to eat, they dont gain weight, they dont feel better, they dont have more energy. Most DIPG patients get feeding tubes inserted during their final days, when the tumour steals their ability to swallow. Its done to treat their desperate parents, but not them. Feeding your sick child is as instinctive as it gets. But there are risks to inserting a feeding tube, Brar tells Stellas parents. Tubes can get infected.

Continued on next page

TARA WALTON/TORONTO STAR

Its October, and Stella continues to deteriorate. Her mothers, family and friends keep a constant watch.

ON ON0 V2

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2012 TORONTO STARA7

> >

STELLAS STORY

called Angelas Airplane. She settles into Mishis lap, beside Stellas head. The room listens while Mishi reads the book about a little girl who wants to fly an airplane, just like Stella did when she visited the cockpit during the trip to Sesame Place in Pennsylvania. Again, Gracie shouts when it is finished. Mishi patiently starts again, as everyone in the room thinks their private thoughts about lifes inexplicable injustice, and growing up, and all the things Stella might have been, had she had the chance. At 8:15, the Mount Pleasant Visitation Centre directors roll up in a black Cadillac, not their usual van. Theyve agreed to carry Stella to the Hospital for Sick Children for her autopsy in the back seat, not on a stretcher. It is a first for the funeral home, says funeral director Jeannette Harrison. The family dims the lights of the house and lights candles, setting them in glass jars along the path from the bedroom right down the front steps. Mishi and Aimee are left alone in the dark room with their daughter for the last time. They kiss her cheeks, stroke her chest, rub their faces against hers, whisper into her ears. Goodbye, Baby, Mishi says. Aimee wraps a fuzzy white blanket around Stella and lifts her up. Thats my girl, she says. This is how we are walking to the car. Stellas passage from this life is candlelit. The soundtrack is a symphony of crying a quick pant, a loud wail, Gracies wounded yelps. It is the beautiful sound of sadness. Family members line the Cadillac with their candles as our beautiful, brave, funny little girl is put into the back seat, her head on Harrisons lap. Harrison strokes her hair the entire way to the hospital. You are well loved, she tells Stella Joy. You will always be loved by many people. Aimee and Mishi watch the red tail lights of the Cadillac glow down the street, carrying their daughter away. Above them, a half-moon glows above misty clouds. Three stars shine down.

Catherine Porter can be reached at cporter@thestar.ca

Its way harder to see her like this than to have her go

Continued from previous page

They can leak and cause the patient to aspirate. Stella would have to spend a couple of days in hospital for the tube to be inserted. Were medicalizing something that is the natural dying process, Brar says. Mishi and Aimee have promised, since Day 1, not to medically prolong Stellas dying. They want their daughter to live, but not like this. They keep by her bedside, never leaving the house for more than 10 minutes. They stay awake at night to watch her. They count the leaden seconds between her breaths: 17. Dying is a physically hard process, Warnick says. Its parallel to giving birth. It tends to be drawn out. It is not easy. The longest shes seen a child go without food or water is 12 days, she says. The morning of day 13, Mishi breaks. She cant watch her daughter slowly die for one more second. Its way harder to see her like this than to have her go, she says. She escapes to the basement and sleeps until 3 in the afternoon, leaving Aimee to sit with Stella, tenderly cleaning out her mouth with baking soda and water, squeezing drops into her red eyes, kissing her fingers. Outside, the sun gleams brilliantly, oblivious to the tragedy unfolding below. By 5 p.m., Mishi has resurfaced. She lays out pieces of fabric on the floor of the living room. They are hugs pictures and messages on strips of cotton dropped off by friends to wrap around Stella. The house around her is still. Suddenly, a panicked shout emerges from the bedroom. Mishi strides toward it and is met by a stampede of women Heather, Auntie Andgie, her mother-in-law, Marilyn Emery.

They wail, pant, pound the wall and rush to the bathroom to be sick. Mishi slips inside the bedroom to hold her daughter for one last breath. AS IF TELEPATHIC, family members and friends storm the house. Each goes directly to the bedroom. Ill always keep your hugs in my heart and your kisses in my pocket, Mishis mother, Margaret Mohr, sobs. You are such a special girl, Auntie Heather says, kissing Stellas calves. We love you, says Aimee, lying beside Stellas body and stroking her left hand. She and Mishi have changed their baby into her final outfit: comfy blue pyjama bottoms, pink striped Dora socks, a pink sweater with burgundy polka dots on top of a white T-shirt featuring a little girl dancing in the

stars. Her favourite stuffed doll, Oopsie Daisy, is tucked into her left armpit. In the soft afternoon light, Stellas face looks blue. Her eyes are sunken and ringed with purple. They are half-open. Her ears stick out. Her forehead rises prominently. Whats most striking about her, though, are her hands. They are curled into cups, the forest green nails turned up. They were being held when she died and now they are frozen like that. Stella was never alone in her short life. She was loved fiercely and abundantly, right to death. For the next three hours, Stellas family and friends sit with her, curl up nearby, talk to her, stroke her. At one point, seven people lie around her on the bed. The mood in the room sinks to despair, then surfaces for laughter before descending again. Aimees stepmother Nanny Sandy drives to the liquor store for a case of red wine. Many glasses are poured. Hey Stellie, you did it, Warnick says when she arrives. Stellas cousin and best friend Gracie brings a new book into the room. Its

EREAD AVAILABLE

Catherine Porter kept a journalists diary as she joined Stella and her parents throughout their journey. Stella is a compelling read, a different take on the story. Its available at stardispatches.com

TARA WALTON/TORONTO STAR

Parents Aimee, left, and Mishi say their goodbyes to Stella, 3, before she is taken away to Sick Kids hospital on the back seat of a funeral home Cadillac. Stella died just after 5 p.m. on Oct. 22.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- If I Am Missing or Dead: A Sister's Story of Love, Murder, and LiberationDa EverandIf I Am Missing or Dead: A Sister's Story of Love, Murder, and LiberationValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (72)

- Stella Joy, Part II: Every Precious MomentDocumento4 pagineStella Joy, Part II: Every Precious MomentToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Maria Selvina Hasni Dihe 2020510479 Sastra Inggris Uas: Prose StudiesDocumento14 pagineMaria Selvina Hasni Dihe 2020510479 Sastra Inggris Uas: Prose StudiesMaria DiheNessuna valutazione finora

- Incredibull Stella: How the Love of a Pit Bull Rescued a FamilyDa EverandIncredibull Stella: How the Love of a Pit Bull Rescued a FamilyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Caregivers JumpDocumento2 pagineCaregivers JumpSaerom Yoo EnglandNessuna valutazione finora

- Chasing The Lights: A CT Journey, Book 1: Chasing The Lights Series, #1Da EverandChasing The Lights: A CT Journey, Book 1: Chasing The Lights Series, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Asylum: A Breath-Taking Psychological Suspense ThrillerDa EverandThe Asylum: A Breath-Taking Psychological Suspense ThrillerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Imaginary Veterinary Book Two: The Lonely Lake MonsterDocumento35 pagineThe Imaginary Veterinary Book Two: The Lonely Lake MonsterLittle, Brown Books for Young Readers100% (6)

- Ni'il: Waking Turtle: Book Three of the Ni'il TrilogyDa EverandNi'il: Waking Turtle: Book Three of the Ni'il TrilogyValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- Ocean's Fire: Book One of the Equal Night TrilogyDa EverandOcean's Fire: Book One of the Equal Night TrilogyValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- The Family Doctor Chapter SamplerDocumento34 pagineThe Family Doctor Chapter SamplerAllen & UnwinNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes For TestingDocumento6 pagineNotes For Testinggfm46332Nessuna valutazione finora

- Walking into the Wind: Being Healthy with a Chronic DiseaseDa EverandWalking into the Wind: Being Healthy with a Chronic DiseaseNessuna valutazione finora

- The Essence of Change: Book Two of the Victors SeriesDa EverandThe Essence of Change: Book Two of the Victors SeriesNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Review of Five Feet ApartDocumento6 pagineBook Review of Five Feet ApartCalliope ZeleniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mother From Hell: Two Brothers, a Sadistic Mother, a Childhood Destroyed.Da EverandMother From Hell: Two Brothers, a Sadistic Mother, a Childhood Destroyed.Nessuna valutazione finora

- SparkedDocumento27 pagineSparkedAnaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pittston Dispatch 09-02-2012Documento71 pagineThe Pittston Dispatch 09-02-2012The Times LeaderNessuna valutazione finora

- All These LivesDocumento7 pagineAll These LivessarahwylieNessuna valutazione finora

- Arch270 Lab 1Documento5 pagineArch270 Lab 1Kenth GomezNessuna valutazione finora

- NYSPA Paper Caring MomentsDocumento11 pagineNYSPA Paper Caring MomentsHarold FontekNessuna valutazione finora

- Phil224 Notes 10Documento5 paginePhil224 Notes 10Amalia 2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- EmailDocumento3 pagineEmailmimiyueeNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Women 1 DayDocumento13 pagine10 Women 1 DayEmer Emily Ellis-NeenanNessuna valutazione finora

- MATH303 Demo 9Documento4 pagineMATH303 Demo 9nathaniel coletoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2024-01-29 Municipal Permitting - Flushing Out The Nonsense enDocumento37 pagine2024-01-29 Municipal Permitting - Flushing Out The Nonsense enToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Application of The Convention On The Prevention and Punishment of The Crime of Genocide in The Gaza StripDocumento29 pagineApplication of The Convention On The Prevention and Punishment of The Crime of Genocide in The Gaza StripToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Play Dressup With Our Royal Paper DollsDocumento2 paginePlay Dressup With Our Royal Paper DollsToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruling On Access To Trump ArraignmentDocumento6 pagineRuling On Access To Trump ArraignmentToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Succession Bingo Board SMDocumento1 paginaSuccession Bingo Board SMToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Canadian Forces Administrative Order (CFAO 19-20)Documento3 pagineCanadian Forces Administrative Order (CFAO 19-20)Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Metrolinx - Metrolinx Statement On Eglinton Crosstown LRTDocumento1 paginaMetrolinx - Metrolinx Statement On Eglinton Crosstown LRTToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- ETFO AgreementDocumento2 pagineETFO AgreementToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Succession Bingo Board SMDocumento1 paginaSuccession Bingo Board SMToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Coronation Order of ServiceDocumento50 pagineCoronation Order of ServiceCTV News100% (5)

- Ruling On Access To Trump ArraignmentDocumento6 pagineRuling On Access To Trump ArraignmentToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Nick Nurse Relieved of Head Coaching DutiesDocumento1 paginaNick Nurse Relieved of Head Coaching DutiesToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulletin Licence PlateDocumento1 paginaBulletin Licence PlateToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Michele Landsberg Introduces Marian XDocumento1 paginaMichele Landsberg Introduces Marian XToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter Bill 39Documento1 paginaLetter Bill 39Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Ontario Deaths in Custody On The Rise 2022Documento16 pagineOntario Deaths in Custody On The Rise 2022Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- COVID-19 Vaccines - 2022 Independent Auditor's ReportDocumento36 pagineCOVID-19 Vaccines - 2022 Independent Auditor's ReportToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Pollara EconoOutlook2023Documento18 paginePollara EconoOutlook2023Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- COVID-19 PANDEMIC - Specific COVID-19 Benefits - AG ReportDocumento92 pagineCOVID-19 PANDEMIC - Specific COVID-19 Benefits - AG ReportToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Overview Report: Fundraising in Support of ProtestorsDocumento61 pagineOverview Report: Fundraising in Support of ProtestorsToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Summit Series Game 6Documento1 paginaSummit Series Game 6Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Dominic Cardy's Resignation LetterDocumento2 pagineDominic Cardy's Resignation LetterToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Dora Award WinnersDocumento7 pagine2022 Dora Award WinnersToronto Star100% (2)

- Hockey Sept 29 1Documento1 paginaHockey Sept 29 1Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Summit Series Game 5, From The ArchivesDocumento1 paginaSummit Series Game 5, From The ArchivesToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Star Sept. 5, 1972Documento1 paginaThe Star Sept. 5, 1972Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Hockey Sept 25 26Documento1 paginaHockey Sept 25 26Toronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Dora Award WinnersDocumento7 pagine2022 Dora Award WinnersToronto Star100% (2)

- Game 4 Summit SeriesDocumento1 paginaGame 4 Summit SeriesToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Sept. 7 Toronto StarDocumento1 paginaSept. 7 Toronto StarToronto StarNessuna valutazione finora

- Trainspotting 2 Clip Comparison EssayDocumento3 pagineTrainspotting 2 Clip Comparison EssayKira MooreNessuna valutazione finora

- MonologuesDocumento7 pagineMonologuesJiggy Derek Mercado0% (2)

- Poetry of MourningDocumento94 paginePoetry of MourningAlessandra Francesca100% (1)

- Hijikata Tatsumi - From Being Jealous of A Dog's VeinDocumento5 pagineHijikata Tatsumi - From Being Jealous of A Dog's VeinStella Ofis Atzemi100% (1)

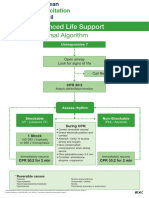

- Advanced Life Support - A0 PDFDocumento1 paginaAdvanced Life Support - A0 PDFiulia-uroNessuna valutazione finora

- Cathy 1 Dom and RubyDocumento12 pagineCathy 1 Dom and Rubyapi-301037423Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sant Longowal Muder CaseDocumento2 pagineSant Longowal Muder CaseMaisha AmbindwileNessuna valutazione finora

- Dead Rising Guide PDFDocumento28 pagineDead Rising Guide PDFMarcel Ivan Rojas Rodriguez100% (1)

- The Writer Also Uses Extremely Effective and Influential LanguageDocumento2 pagineThe Writer Also Uses Extremely Effective and Influential LanguageDheer Bhanushali100% (2)

- Locsin vs. Court of Appeals 206 SCRA 383, February 19, 1992 PDFDocumento2 pagineLocsin vs. Court of Appeals 206 SCRA 383, February 19, 1992 PDFTEtchie TorreNessuna valutazione finora

- Dmci Corporate PortalDocumento1 paginaDmci Corporate PortalAngelito Temblor DionaldoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer PDFDocumento2 pagineRudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer PDFIngeborg SchweitzerNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To AgeingDocumento21 pagineIntroduction To AgeingLinh LeNessuna valutazione finora

- TheWalkingDead 01 Lores 1405641515 PDFDocumento33 pagineTheWalkingDead 01 Lores 1405641515 PDFpride31100% (8)

- Death Penalty 1.1Documento12 pagineDeath Penalty 1.1Mishi Reign A. AsagraNessuna valutazione finora

- Dorian Gray EssayDocumento5 pagineDorian Gray EssayAndrea Rodríguez GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Othello SummaryDocumento11 pagineOthello Summaryaditi_123456Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient Egyptians Knowledge Organiser v1Documento1 paginaAncient Egyptians Knowledge Organiser v1RyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Life Essay PDFDocumento3 pagineLife Essay PDFAnnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bernabò Visconti: Lord of MilanDocumento4 pagineBernabò Visconti: Lord of MilanNupur PalNessuna valutazione finora

- People vs. VerzolaDocumento2 paginePeople vs. VerzolaAV AO100% (2)

- Dewey Gram (Gladiator)Documento3 pagineDewey Gram (Gladiator)AssignmentLab.com0% (1)

- Cremation Cost SheetDocumento2 pagineCremation Cost Sheetapi-622084072Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Does The Bible Say About ETERNAL JUDGMENT?Documento87 pagineWhat Does The Bible Say About ETERNAL JUDGMENT?MustardSeedNewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Humour and DeathDocumento13 pagineHumour and DeathBrian JennerNessuna valutazione finora

- Toni Tristan - ZodiacDocumento4 pagineToni Tristan - Zodiacapi-280976105Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marion Minerbo - Two Faces of ThanatosDocumento23 pagineMarion Minerbo - Two Faces of ThanatosSLNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Settlement Proceeding Flow ChartDocumento1 paginaJudicial Settlement Proceeding Flow ChartRobi SuaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Sotomayor DissentDocumento17 pagineSotomayor DissentUSA TODAYNessuna valutazione finora

- Ozamiz Mayor ParojinogDocumento4 pagineOzamiz Mayor ParojinogbumbleshetNessuna valutazione finora