Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

ROBERTSON Narratives of Resistance 2012

Caricato da

Francisco X. CancinoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ROBERTSON Narratives of Resistance 2012

Caricato da

Francisco X. CancinoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

New Global Studies

Volume 6, Issue 2 2012 Article 3

Narratives of Resistance: Comparing Global News Coverage of the Arab Spring

Alexa Robertson, Stockholm University

Recommended Citation: Robertson, Alexa (2012) "Narratives of Resistance: Comparing Global News Coverage of the Arab Spring," New Global Studies: Vol. 6: Iss. 2, Article 3. DOI: 10.1515/1940-0004.1172 2012 New Global Studies. All rights reserved.

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Narratives of Resistance: Comparing Global News Coverage of the Arab Spring

Alexa Robertson

Abstract

A rapidly evolving media ecology is posing significant challenges to actors in the halls of power, on the streets of popular dissent, and in the global newsrooms that connect these sites to the imaginations of media users throughout the world. It is a complicated tangle of relations, and difficult questions arise about which theoretical instruments are most useful when trying to unpick it. Global news coverage of the "Arab Awakening" of 2011 is fertile terrain for an exploration of some of these questions. The article compares how popular resistance is narrated by newsrooms with different reporting traditions, and reflects on how global audiences are positioned in relation to such events. The theoretical discussion is organized around the notions of media witnessing and cosmopolitanism. The empirical analysis is based on reports from over 1000 news stories broadcast on Al Jazeera English, which claims to give a voice to the voiceless, and BBC World, which has a tradition of reporting the world from the vantage point of elites. The results indicate that the reporting gaze is gendered differently, and that there are also intriguing differences in the way audiences are situated by the two broadcasters. KEYWORDS: global media, Al Jazeera, Arab Spring, media witnessing, cosmopolitanism Author Notes: This study builds on work supported by the Swedish Research Council grant 421-2009-1698/90169801. The author would like to thank Christina Archetti and Ester Pollack for their comments and Erik Jnsson for his coding assistance.

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

The Protester was named Person of the Year in 2011 by Time Magazine. From the Arab Uprising to Occupy Wall Street and post-Duma-election Moscow, dissenters raised their voices not only to challenge their own governments, but also to speak to a global audience. The protests are reminders that political change and changes in media technology are companions; that politics can be contained in national settings only with difficulty; and that people have become accustomed to witnessing the live coverage of history, present in time if not space. The protests of 2011 rode on a wave of technological advances that placed unforeseen communicative power in protesters hands - literally, in the form of the smartphone. Much attention has been paid to how the new media ecology offers activists novel opportunities to communicate independently of mainstream news media (Bennett 2003; Donk et.al. 2004; Dahlberg & Siapera 2007), and in the rush to make sense of new media revolutions, it is assumed that mainstream media are constrained by old practices and formats. This is far from the case. Journalists continue to speak to their audiences through the camera lens, but they also do so through twitter streams, blogs and other forms of online journalism. Mainstream media reports have also analyzed the role of social media in their coverage of political turbulence and draw on crowdsourced material in new ways (Robertson 2012). The practice of embedded journalism has morphed, with journalists following dissenters into the fray, where they once followed the troops. With the shifting of geo-political interests and outlooks in recent years, television news depictions of dissent may also have changed. Contrary to claims about the operation of universal news values shaping representations of protests, preliminary analyses indicate that the dissent of 2011 - in the Arab world, in Russia, in debt-ridden European capitals and in the occupied financial districts of North America as well as Africa and Asia - was reported differently in different media, despite the fact that they all broadcast within the same few hours (or indeed 24/7) to the same global audience. Some protests are clearly more politically acceptable to some news media than others, and some journalists actively champion some of them. This crucial field of mediated democracy has yet to receive sustained, systematic and comparative investigation across time, space, media or different protest issues. As Cottle (2011) has argued, concerted mapping and inquiry across the news media field is required. A preliminary attempt to respond to this need is reported in what follows. The purpose of this article is to compare how popular resistance is narrated by newsrooms with different reporting traditions, and to reflect on how global audiences are positioned in relation to such events. The theoretical discussion is informed by ideas from the theoretical discourse on cosmopolitanism and media witnessing. The empirical analysis is based on reports from over 180 broadcasts aired on Al Jazeera English, which claims to give a voice to the voiceless, and BBC World, which has a tradition of reporting

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

the world from the vantage point of elites. Results suggest that Secretary of State Clinton was right when she said, in March 2011, that AJE was winning the information war. EXPLORING MEANING-MAKING IN A MEDIATED GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT The present study is part of a larger inquiry into the role of global media in paving the way for cosmopolitan democracy. It compares news that is broadcast to a global audience by established Western channels with news that is broadcast by channels claiming to provide alternative perspectives (sometimes referred to as counter-hegemonic media or outlets aiming to reverse the flow). In focus is the tension between othering mechanisms, which can be thought detrimental to democracy, and respect for and representation of diversity, which can be thought to promote it. The red thread running through all of the component studies is whether such alternative global broadcasters report the world differently from mainstream channels with their roots in the West. The ability to deal with diversity is essential to cosmopolitanism. Silverstone expressed it well. What is involved, he says, is the opening up of global spaces in which we develop a sense of there being an elsewhere; a sense of that elsewhere being in some way relevant to me; a sense of my being there (Silverstone 2007: 10). As argued elsewhere (Robertson 2010), imagination and storytelling are intrinsic to the construction of cultural and political identities under globalization (as at other times). Following Delanty (2006: 37), the point of departure for this work is that cosmopolitan imagining articulates the social world through cultural models in which codifications of both Self and Other undergo transformation. The analysis of television news stories aimed at global audiences provides fruitful ground in which to cultivate an understanding of such processes. Previous research has shown that journalists themselves often stress the importance of opening different windows on the world; of proffering different perspectives on the events unfolding in that world; and of letting different voices be heard when those events are recounted (Painter 2008; Robertson 2005). Among them are journalists working for two global channels associated with Europes Others: Russia Today (RT) and Al-Jazeera English (AJE). As an AJE journalist put it, soon after the channel began broadcasting in 2006: You have to report the world from many different perspectives in order to report the world back to itself (Robertson 2010). The present study asks whether AJE does as it promises - whether it reports from different perspectives than an established broadcaster like BBCW. An attention to narrative is central to this research, because insights into the preconditions for the emergent cosmopolitan understandings, and perhaps even identities, on which democracy in the global era rests, can be gained not just

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

by looking at what is reported about the world, but also how it is reported. At the heart of this inquiry is an interest in interpretive frameworks of common, cultural references and thematic codes, incarnated in master or model narratives which help make things comprehensible and relevant to the public (Birkvad 2000: 295). Documenting these, and explaining how they work, presents a methodological challenge, but the effort can be worth it, as it can teach us much about cultural power in globalized societies. Master narratives tend to be experienced as something innocent, because they are naturalized (Barthes 1993: 131). What attention to narrative attempts to gain analytical purchase on is the generation of these sorts of understandings - what is taken for granted, or that which goes without saying. An attention to narrative is no less worthwhile in times of turbulence like the Arab Spring, when things that had long been taken for granted suddenly became the focus of resistance, and protesters throughout the region made it clear that there was much to be said. MEDIA WITNESSING From the outset, the Arab Spring was an iconic uprising, with struggles for control waged over discursive spaces as well as over physical sites like streets and squares. It is symptomatic that one of the first images to go viral in January 2011 contrasted the local with the global, and the traditional with the new. It depicted traditionally-dressed men in a street protest, making the time-honoured V sign that stands for both victory and peace, holding placards in Arabic, and a handmade sign with the single, but pregnant word Facebook. Less striking but perhaps more telling is an image that crops up in AJE coverage of the crackdown in Libya on February 21st, an illustration of the distinction made by Boltanski (1999) between levels of spectatorship.

The practice variously referred to as crowd-sourcing, participatory or citizen journalism has become an important component of much newsgathering. What news professionals once eschewed (grainy images, shaky footage captured by handheld devices, even material of dubious provenance) they have

Published by De Gruyter, 2012 3

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

come to rely on and, in some cases, celebrate, insofar as it bears the credentials of the eyewitness. The way new media content is recontextualized by old media practitioners gives insights into how journalistic practice is changing (LorenzoDus & Bryan 2011), is thought by some to be democratizing in itself, and resonates with Dayans observation that media events are no longer spoken by the single, monolithic voice of the nation (Dayan 2010: 29). The role played by user-generated content in coverage of the 2011 unrest has a bearing on one of the concepts underpinning the present discussion - that of media witnessing (Frosh and Pinchevsky 2009; Peters 2009; Ellis 2009; Hoskins and OLoughlin 2010). As Scannell (2004: 582) reminds us, news structures and routines are designed to produce effects of truth, the purpose of which is to reassure us that we can believe what we are told and shown. The consumption of first-person narratives is a way of being there. Building on Boltanski, Scannell writes that all of those who are there in different capacities, inhabiting different dimensions of spectatorship - be they participants, eye-witnesses, camera crews or reporters act as witnesses to the truth of an event for the sake of absent audiences. They do this so that anyone and everyone who watches will own the experience (Scannell 2004: 582). In the Al Jazeera still picture reproduced above, the participant protester holds up his foot as testimony to having physically witnessed the brutal response of the Libyan security forces. A second witness documents the experience with his mobile phone camera, an act witnessed in turn by a third, professional, cameraman. Because the moment was broadcast live, on global television, it produced a fourth dimension of witness - a viewer inhabiting Silverstones mediapolis, participating in the moment in time if not space. Frosh and Pinchevsky (2009) use the notion of media witnessing to denote the systematic and ongoing reporting of the experiences and realities of distant others to mass (and increasingly global) audiences. Like Peters (2009:24), they distinguish between three different dimensions, in a similar way that the aforementioned image can be related to. Witnessing refers simultaneously to the appearance of witnesses in media reports, the possibility of media themselves bearing witness, and the positioning of media audiences as witnesses to depicted events. The point of the distinction - and, conversely, the interweaving of the three manifestations into a single concept - is that it does justice to the complexity of mediated interactions. Whether performed by a media professional or an ordinary person with a mobile phone camera, media witnessing represents a shared world, shared, that is, by both viewers and those depicted (Frosh & Pinchevsky 2009:

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

10). In some respects, the distant viewer owns the event more than the person on the ground. Spatial and temporal extension means that those who are not physically present are better informed about what is going on (they can see the big picture) than the people directly experiencing event, and perhaps even the reporter-spectator, whose account is reliant, for contextualization and sensemaking, on the anchor in the studio, who conducts the choir of witnesses. Just as the individual chorister is not the equal of the conductor, neither is the ordinary mobile phone-user the equal of a media professional. Not all crowdsourced footage will reach television audiences, and the journalist (or rather newsroom) is the guardian of the repeatability of events (i.e. the footage can be reproduced and recontextualized when the newsroom chooses, as maintained by Lorenzo-Dus & Bryan 2011). Frosh and Pinchevsky (2009: 11) claim there is an institutional politics of contemporary media witnessing that informs how witnessed worlds are represented as shared and who may depict them and appear in them. This assumption (for it has not actually been verified by empirical research) informs the present approach to the empirical material, together with Cottle and Rais (2008) notion of communicative frames. Frosh and Pinchevskys assertion will in what follows be operationalized as a question to be posed to the television texts. In reporting of the mobilization for democracy in 2011, who is entrusted with the task of depicting the witnessed world of protest on BBCW and AJE, who appears in this world, and how do they connect with us? And what Cottle and Rai (2008: 167) refer to as a reportage frame, which provides thick descriptions of reality by bearing witness and recovering something of the lived, experiential reality of news subjects and/or providing depth, background and analysis that purposefully seeks to move beyond the temporal/spatial delimitation of news event reporting will be kept in mind when analyzing how sources are used by these media professionals. THE EMPIRICAL CONTEXT As anyone who attempts systematic analysis of global television knows, it is impossible to construct a perfect sample, with global schedules tending to be more erratic than domestic ones. This is presumably a reflection of the fact, referred to above, that audiences can be assumed to be online as often as on

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

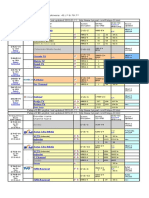

couch, and a reminder that television is a flow, and should ideally be treated as such. (This, of course, is easier said than done.) TABLE 1. NUMBER OF ITEMS DEVOTED TO THE ARAB SPRING (AS) IN RELATION TO THE TOTAL NUMBER OF ITEMS IN FOUR GLOBAL TELEVISION NEWS PROGRAMS, 131 JANUARY 2011.

Length (mins) share of total sample (length) 23 15 19 42 99 # items share of total sample (items) 28 12 15 44 99 # AS items % of own items devoted to AS 16 18 4 18 16 time AS items (mins) 161 132 30 268 591 % of own time devoted to AS 20 26 5 18 17

BBCW (31 progs) CNN ID (18 progs) RT (31 progs) AJE (31 progs) Total

774 510 635 1418 3337

395 167 211 617 1390

65 30 9 122 226

As part of a larger study, a preliminary analysis of the output of four global television news channels during the tumultuous weeks at the beginning of 2011 has been conducted. Two of the channels are Anglo-American and old in global television terms, and two are new in that they claim to provide alternative perspectives on the world from non-Western vantage points, and only began operations a few years ago (2005 and 2006). Flagship news programs from these channels were coded with a view to depictions of popular dissent, and to depictions of the world in which it was contextualized: the commercially-funded (but public-service-born) BBC World News, broadcast from London at 10pm CET; commercially-funded CNNIs International Desk, a 60-minute broadcast from Washington at 7pm CET; Kremlin-financed Russia Today News (RT), broadcast from Moscow at 7pm CET; and News (30 minutes) or Newshour (60 minutes) broadcast from London or Doha at 7 or 8pm CET by Al Jazeera English (AJE), which has no commercials and is financed by the Emir of Qatar. The reason that the AJE sample includes two different programs is that the 30 minute

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

News from London, selected as the unit of analysis for various reasons, 1 was often replaced by a 60-minute Newshour, without warning. This was especially the case during the tumultuous weeks between the posting of Bouazizis self-immolation on Facebook and the ousting of Egyptian president Mubarak. That analysis indicates that the Arab Uprising was not given the same attention by all of these channels, as can be seen from Table 1. It is clear that Russia Today played down the significance of popular resistance to authoritarian rule, compared to the other three channels, when it comes to the relative number of items devoted to the Arab Spring in each program (% of own items). It also distinguishes itself in respect of the relatively little airtime given the Arab Spring. Interestingly, however, AJE also gives relatively less time to the uprisings - it devotes less program time to them, relative to other world news, when compared to BBCW and CNNI - which is not what might be expected. It is worth noting in this connection that the world of AJE did not shrink to the Middle East in these weeks, and that considerable attention continued to be paid to Latin America, Africa and other regions. What Table 1 does not show is the finding that CNNs International Desk coverage consisted largely of talking heads that discussed events with each other, to a backdrop of agency footage loops, as opposed to reports filmed and filed by their own correspondents on site. BBC World and Al Jazeera English different in this respect, deploying an impressive contingent of reporters to the region in these weeks. The discussion in the following pages is based on their reports, and the witness they bore to unfolding events. NEWS FROM EVERYWHERE: BBC WORLD AND AL JAZEERA ENGLISH The empirical analysis that underlies the following discussion is based on the 62 main evening bulletins broadcast in January 2011 and several weeks-worth of broadcasts from the following month on these two channels. As mentioned above, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton went on record in March 2011 as saying that the U.S. was losing an information war to competitors like BBC World and most of all Al Jazeera English which, unlike American companies, was offering its viewers real news, and which was changing the minds and attitudes of people

1

An important part of the larger project is to see whether Europe is depicted as Other by channels such as AJE, RT and Chinas CCTV, with their ambition of reversing the flow. For this reason, an attempt has been made to analyze programs that are not only of comparable length (preferably 30 minutes, although this has not been possible in the case of CNNI), character and linguistic target audience, but also ones that target a European primetime audience. For this reason, the 30 minute News program, broadcast from London, is the primary unit of analysis for AJE. When particularly important events are underway, however, this program is often replaced, without warning, by the 60-minute Newshour from Doha.

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

everywhere. 2 Their influence is one reason for their selection. They are also comparable in that British public service broadcasting is an important foundation for AJE journalism. BBCW is one of the worlds oldest global broadcasters, and while viewer statistics for global operators are not unproblematic, it is safe to say that it is one of those most watched: with an estimated weekly audience of 74 million (BBC 2011), it reaches more households (295 million) than what was for years its leading competitor, (200 million). AJE falls in between. By 2011, five years after it went on air, AJE was broadcasting to more than 220 million households in over 100 countries and by its own account was the most watched news channel on YouTube even before the pro-democracy mobilization of 2011. Pressure mounted at this point on cable and satellite providers to distribute AJE in the United States, where it had gained a keen online audience as a result of its high profile in these events, during which its web traffic rose by 2500 percent (Usher 2011). Under the remit of the state-funded World Service, BBCW is dependent on commercial revenues. The BBC, in both its domestic and global incarnation, represents the liberal or Anglo-American model of media and politics, which entails a professional ethos centered on the principal of objectivity (Hallin and Mancini 2004: 227). On the other hand, most people associated the name Al Jazeera, until recently, with an Arabic news service popular with Muslims in the Middle East and diaspora that became an influential but controversial news source during the Bush administrations war on terror. The research reported here concerns the channel that broadcasts news in English across the globe, around the clock. It operates from the same base in Doha, and is financed the same way (by the Emir of Qatar and commercial revenues), but differs from the Arabic one in a number of significant ways (although it has yet to attract the same amount of scholarly attention, on this see Seib 2012 and Figenschou 2010: 87). During the period analyzed here, AJE broadcast twelve hours a day from its Doha headquarters, and four hours a day from its regional centers in Kuala Lumpur, London, and Washington respectively. Rather than news from nowhere, it could thus be said to broadcast news from everywhere, or at least to reflect an ambition to provide a news service that is global in more than name and viewership. In this respect, it differs from BBC World, which operates from London (as well as Berlin-based Deutsche Welle, Marseilles-based Euronews, Moscow-based Russia Today and Beijing-based CCTV). The journalists working for AJE also represent an unusually cosmopolitan mix, even for the demographic of the global newsroom. Unlike BBCW, AJE uses

Hillary Clinton addressing the U.S. Foreign Policy Priorities Committee on 2 March 2011, www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/03/03/hillary-clinton-calls-al-_n_830890.html (video excerpt), accessed 7/3/11.

2

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

correspondents who file their reports in heavily accented English, flavored by the part of the world from which they are reporting (as well as journalists who speak English like natives). On the other hand, a substantial proportion of the news anchors and senior reporters are familiar to viewers of established Anglo-Saxon companies, not least ITN and CNN, which they left to work for AJE. It is not uncommon to read that these journalists changed newsrooms in search of new perspectives, or out of frustration with the tendency to over-report some parts of the world (the U.S. and Europe) and under-report others (Africa and Asia). From its inception, AJE has advertised its intention to report differently. Its mission is to offer a voice to a diversity of perspectives from under-reported regions (AJE 2010). MEDIA WITNESSES Inspired by Boltanski and Scannell, the BBCW and AJE items relating to the Arab Spring were read, with attention paid, after an initial viewing, to testimonies given by different sorts of witnesses, or on different levels of spectatorship. In these reports, who tells us what is happening? TABLE 2. DISTRIBUTION

OF SOURCES (PEOPLE WITH SPEAKING PARTS, COUNTED ONCE FOR EVERY NEWS ITEM THEY SPEAK IN) IN REPORTS CONCERNING THE ARAB SPRING ON BBC WORLD 9PM CET AND AL JAZEERA ENGLISH 8 PM CET, MONDAY 10 JANUARY - SUN 30 JANUARY 2011.

total sources men % men women % women vox pop/ activist % vox pop/ activist 56 52 vox named elite % elite

BBCW AJE

57 76

47 58

82 76

10 18

17.5 24

32 40

7 18

19 29

33 38

The sources referred to in Table 2 are the sources of testimony. In both BBCW and AJE coverage, the majority are non-elites: activists; people who have taken to the streets to join the protesters or to witness the events themselves and in many cases to document the violence with which they were met; or people who had left their homes, the better to protect them. In BBCW reporting, those given a speaking part - activists and elites alike - are almost always men (82%). They are in the majority in AJE too (76%), but there are differences between the two broadcasters use of sources that are worth noting. Of the 10 times a woman was coded as having a speaking part in BBCW, that woman was Hillary Clinton in 4. On AJE, women occupied a more central place in narratives of the protests than is reflected in quantitative analysis. They are often pictured as leading the men into

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

action - modern-day (and more demurely dressed) versions of Liberty in the 1830 painting by Delacroix. And they are often singled out in what on other channels can seem like a sea of young men. On January 25th, for example, one of the several AJE reporters on the ground told viewers that when an activist - a young woman - was recounting how she had turned out to call for a regime change, she was interrupted. And just take a look by whom, said the (woman) reporter, as an older woman came up to the microphone, clamoring to be heard.

Were suffering. Were Egyptians. We love Egypt but stop this. We want to eat, we want to live, we want our children to live. On this day - which can serve as an instructive illustration - the political turmoil in Lebanon is framed in BBCW as largely a matter of negotiations among elites. On AJE, events in Lebanon mirror those in Tunisia and Egypt: the story is one of protesters taking to the streets to express their frustration over the government and their desire for change. 3 The following night, the AJE broadcast opened with an excerpt of an interview given over mobile phone, despite the bad quality, by a young Egyptian woman, identified by name, who found herself in a crackdown by security forces as she was on the phone to Al Jazeera. And Im trying to run now because theyre targeting everyone, theyre taking everyone, theyre taking everyone and theyre beating everyone and Im running [inaudible] Oh my

This is not to suggest that protesters and Al Jazeera always saw eye-to-eye: in another city on this day, an AJ satellite truck was set alight by demonstrators.

3

10

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

god, theyre coming into the building, theyre trying to take anyone whos running away. Sorry, excuse me, hello? In Tunisia, AJE viewers had also been witness to disrupted testimony. On January 18th, the program was co-anchored by a woman in London and another on the streets of Tunis, who presented a report filed by her male colleague in another part of the city. Viewers could watch the reporter talking, in English, to a youth on the street when police tried to stop the interview. The camera continued to roll as the AJE reporter reminded the policeman that his prime minister had declared freedom of the press. They stopped the conversation, said the reporter, but they cant stop the demonstrations. A young woman came up to him, and spoke directly to the camera (in English).

Im 19 years old. I am here to fight. To fight for my freedom and for my country. Reporter: Why are you unhappy with the new unity government? Girl: Because its the same government, nothing has changed, not really! Another order of witness - already in evidence in the examples given above but given statistical presence in Table 3 - is the reporter himself. Or herself, as was often the case in AJE.

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

11

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

TABLE 3. NUMBER OF ITEMS FILED BY A REPORTER (AND NOT JUST READ BY THE ANCHOR) IN BBC WORLD 9PM CET AND AL JAZEERA ENGLISH 8 PM CET, MONDAY 10 JANUARY - SUN 30 JANUARY 2011, DISTINGUISHED BY GENDER AND WHETHER THEY ARE ON SITE. MAE= MIDDLE-AGED ENGLISHMAN

# AS items with reporter BBCW AJE 39 44 Men % men MAE % MAE Women % women on site % on site

32 28

82 63

29 4

74 9

7 16

18 36

25 40

64 91

Whatever the gender, it is worth noting the measures taken - often at personal risk - to deploy correspondents on site. By January 29th, the fifth Day of Rage, Lyse Doucet was anchoring the BBCW broadcast from a Cairo rooftop. Departing from the usual programing ritual, an unusual quality is given to the live-ness so often claimed to be an integral part of 24/7 news. Local Cairo time is repeatedly mentioned, as well as indicated on screen, and Doucet gives us our bearings in space as well as time:

If I look on the streets below me there are dozens of young mean carrying whatever they could find to protect this neighborhood. Theyre carrying sticks, Ive seen somebody carrying a fieldhockey stick...

12

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

Her colleague on the ground is not live (it is light when he addresses us, while a night sky backgrounds Doucet on her rooftop), but his report is live in another sense. He, too, looks around as he talks, getting his bearings, and helping us to get ours.

The main square of the Arab worlds biggest and most important capital is like a war zone. A discursive connection is formed in such coverage between the people on the ground in Tunisia and Egypt (protesters and journalists alike) and the people witnessing events from afar (newsroom anchors and viewers around the world). Anchors in London and Doha continually ask their colleagues on stormy streets what they are witnessing. Sometimes the anchors see more than the correspondents - as for example on January 30th, when a few crowd-sourced pictures finally made it out of Alexandria, which was under a news blackout. Continuous coverage of the protests prompted authorities to shut down Al Jazeeras operation in Egypt earlier on Sunday, said the anchor, and went on to remind her viewers that they were no longer naming their correspondents or identifying their specific locations during live coverage, in order to protect them. With the few Alexandrian shots shown in a loop, the anchor remarks to the correspondent on site (but not on camera) that the pictures are very difficult to get out because the lines of communication are being blocked at every corner, at every turn, to which she replies It has been very difficult for anyone to broadcast anything out of the city. To begin with phones were shut down nationwide and after the phone network had returned internet still remains blocked [...] difficult for us to broadcast any material so these are very valuable pictures indeed [inaudible].

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

13

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

Faced with such attempts to control, or quell, the flow of information, protesters and journalists alike availed themselves of social media. While only three of the items in the BBCW sample explicitly referred to the role of such media, AJE made use of it in several ways, and it is repeatedly a narrative focus. AJE used - and acknowledged - footage taken from YouTube and other amateur sources, it incorporated tweets and citations from blogs in its narratives, and it highlighted the importance of Facebook and Twitter in several reports. On one, broadcast on January 25th, the correspondent explained that Egyptian activists had been inspired by events in Tunisia, and had been using the internet to call for a day of anger. For once, she said, it seems that internet clicks in Egypt have translated into action on the ground. By the time that action had led to a political crisis and violent clampdown by security forces, another sort of digital technology began to feature largely in news reports. Google Earth was used once by BBCW and repeatedly by AJE, bringing viewers from their armchairs closer to the site of unfolding events, a powerful dramaturgical device (see Szerszynski & Urry 2006 for its precursor). Silverstones notion of mediapolis (2007) taps us on the shoulder here. On January 29th, AJE figuratively installed its audience on site, when the anchor told viewers they were looking at live shots from Tahrir Square. People all over the world were invited by journalists from both channels (and CNNI) to join them in witnessing history unfolding before their eyes - to get a sense of being in an elsewhere that was relevant to them. But it was AJEs audience that had frontrow seats. CONCLUSION The events reported in this article have often been referred to as the Facebook Revolution, and the role of Twitter in the Arab Uprisings has been the topic of countless articles. The scholarly literature continues to juxtapose new social media with old media like television. Why then bother studying it? First, it could be argued that a television channel like AJE is new media. In terms of content and convention, television is the shapeshifter fruit of digital convergence, broadcast and consumed online as often as on the familiar box. Its correspondents are as likely to be on Twitter as on camera. Some leading television outlets cannot even be characterized as old in a purely chronological sense. While blogs have been around since the late 1990s, Al Jazeera English did not begin broadcasting until late 2006 - half a year after Twitter was launched. Second, and more importantly, television is where everyday stories about the world are regularly rehearsed. More than traditional print media, the imagery and narrative techniques deployed in television news reporting bestow the medium with the potential to forge immediate connections between viewers in

14

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

one place and the distant others populating their screens. Social media provide a new sort of connectivity, but not necessarily a more compelling one (Grusin 2010; Robertson 2012). As the busy inhabitants of the global village turn increasingly to the internet to skim the facts of breaking news, television broadcasts have been given more scope to go in-depth. This fosters the development of mechanisms which may bring the world closer to viewers on other continents. The use of vox populi is often disparaged for their lack of representativeness and episodic nature. But their dramaturgical function and identification power - their capacity to make distant audiences feel directly addressed and complicit (Robertson 2010) - are reasons for thinking twice before dismissing them. These and other narrative techniques have the potential to make people more comfortable with the diversity on which cosmopolitan democracy rests. It could, of course, equally strengthen the mechanisms that keep the world at arms length through Othering practices. For this reason, comparative research is needed. Silverstone had good reason to remind us that global mediated culture is not homogenous, and that the world appears differently on a channel with its roots in the West than on a channel with other moorings, even if both speak to the same audience at the same time. This analysis has attempted to illustrate that AJE offered an alternative perspective from a mainstream broadcaster like BBCW differences not easily related to the Al Jazeera networks Arab origins. Throughout the weeks studied here, the world of AJE in particular was populated by people on the streets, rather than politicians in official buildings, who were largely conspicuous by their absence. Importantly, the streets were not just those of Tunis, Cairo, Manama and Benghazi - they were also those of European capitals, of Belarus, Albania, the Ukraine and Belgium, where people were depicted as calling for democratic reforms in their own countries. These were seldom anonymous, tending to be identified with names and roles (doctor, ITengineer, art student or member of the youth movement). As Figenschou (2010) found, it is alternative elites - notably young activists -who are interviewed in the AJE studio, rather than established figures. AJE coverage could be said to live up to its aspirations for diversity when assessed in terms of gender. While its loops of repeated raw video, just like the footage played and replayed in other global newsrooms and streamed online, showed largely masculine seas of protest, the reporters on site often managed to find a woman to interview. She may have been in jeans or in traditional Arab dress, but she often spoke English - the better to be able to connect to non-Arab audiences - and gave the impression of being educated. The reporter, too, was often a woman, and while a woman reported on armed conflict from Kabul, her Anglo-Saxon male colleague was filing a report on lesbian rapes and womens empowerment from South Africa. The metanarrative that can be discerned in AJE reporting in the period studied here

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

15

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

was not one that flattered the besieged regimes in any region. The narrative was of resistance by young, peaceful, democratically-inclined and globally-oriented people on the ground to corrupt, old men clinging to power that they had wielded for too long and misused, barricaded in their palatial residences not only in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, but in Uganda, Cte dIvoire and Italy as well. These are narratives about, and recounted by, civil society. While BBC World paid considerable attention to the Arab Spring, and went so far as to co-anchor several programs from Cairo, its overarching narrative of the world emphasized instability and insecurity as opposed to change and hope, and it was told from an elite perspective rather than the vantage point of civil society. The BBCW gaze is male - indeed middle-aged-English-male enough to resemble Monty Pythons Whicker Island (except when Lyse Doucet gives the viewer a tour of Tunis or Cairo). And the story of the Arab Spring is placed against a larger backdrop of a world populated by elites and powered by elite responses. Apart from comparing the narrative features of individual news items and mapping the distribution of the power of definition (begun here with simplistic content analysis of sources), the analytical gaze must in future work rest on the overall dramaturgy of rolling coverage, as Cottle and Rai (2008) so rightly suggest - on the ritual of the news program, and what happens when its routine is interrupted; on the role of the anchor in piecing together an account of turbulent events in dialogue with correspondents on the ground, who are in the thick of things but cut off in other ways: and on their relationship to other witnesses using a variety of new media forms. Like a liturgy with prescribed features (kyrie, sanctus, gloria, agnus dei), the news broadcast at normal times has a familiar tempo (top story, longer piece, telegram block, a bit about the Oscars or Royal Wedding at the end). In the first five weeks of the Arab Spring, AJE abandoned this ritual first, and more often than BBCW. By January 29th, however, BBCW had joined AJE in reporting directly from Cairo, and in giving saturation coverage to the revolution. The anchor remained the priest, through which all the voices were intermediated, but the form of the broadcast changed. Instead of the reporter playing the role of the first-order witness, telling viewers what was happening, global audiences could now see for themselves, and experience events as they unfolded, in real time. The vantage points were different - BBCW viewers joined Lyse Doucet on her rooftop, while AJE viewers looked straight into Tahrir Square - but all were urged to keep the company of the correspondents on site and stay turned, for hours on end, even when nothing was happening and when no one could say how the unscripted event would end. In an age when politics have become increasingly mediated (Thompson 1995; Couldry 2008) and perhaps even mediatized (Krotz 2009; Hjarvard 2008), the way in which news programs frame protests, give voice to dissenters and implicate the people attending the demonstrations from their screen, co-present in

16

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

time but not space, has a bearing on democracy, however conceived, and on broader theoretical debates about (cultural) globalization, discursive power and political change. The year that began with the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt saw the world take to the streets. It was a time for outrage (Hessel 2011), containing the stuff of many narratives of resistance, which in turn contain enough symbolic and discursive material to form the stuff of many scholarly analyses. There is much to be done. REFERENCES AJE (2010) Corporate Profile, http://english.aljazeera.net/aboutus/2006/11/2008525185555444449.html, accessed 9/3/11. Barthes, Roland, 1993 [1957]. Mythologies. London: Vintage. BBC (2011) About BBC World News tv, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-radioand-tv-12957296, accessed 4/7/12. Bennett, L. (2003) New Media Power: the Internet and Global Activism, in N. Couldry & J. Curran, eds. Contesting Media Power: Alternative Media in a Networked World. Oxford: Rowan & Littlefield. Birkvad, S. (2000) A battle for public mythology: history and genre in the portrait documentary, Nordicom Review 21(2): 291-304. Boltanski, L. (1999) Distant Suffering. Morality, Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cottle, S. (2011) Transnational Protests and the Media: New Departures, Challenging Debates in S. Cottle & L. Lester, eds. Transnational Protests and the Media. New York: Peter Lang. Cottle, S. (2009) Global Crisis Reporting. Journalism in the Global Age. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill/Open University Press. Cottle, S. & M. Rai (2008) Global 24/7 news providers. Emissaries of global dominance or global public service? Global Media and Communication Vol 4(2): 157-181.

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

17

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

Couldry, N. (2008) Mediatization or mediation? Alternative understandings of the emergent space of digital storytelling, New Media & Society 10(3): 373-391. Couldry, N., A. Hepp & F. Krotz (2010) Media Events in a Global Age. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. Dahlberg, L. & Siapera, E. (2007) Radical Democracy and the Internet. Houndmills: Palgrave. Dayan, D. (2010) Beyond Media Events. Disenchantment, derailment, disruption, in N. Couldry, A. Hepp & F. Krotz, eds., Media Events in a Global Age. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. Dayan, D. & E. Katz (1992) Media Events. The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. Delanty, G. (2006) The cosmopolitan imagination: critical cosmopolitanism and social theory, The British Journal of Sociology Vol. 57(1): 25-47. Donk, W. et.al., eds. (2004) Cyberprotest: New Media, Citizens and Social Movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Ellis, J. (2009) Mundane witness in Paul Frosh and Amit Pinchevsky, eds., Media Witnessing. Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 73-88. El-Nawawy, M. & S. Powers (2010) Al-Jazeera English. A conciliatory medium in a conflict-driven environment? Global Media and Communication Vol. 6(1): 61-84. Figenschou, T. (2010) A voice for the voiceless? A quantitative content analysis of Al-Jazeera Englishs flagship news, Global Media and Communication Vol. 6(1): 85-107. Frosh, P. (2011) Phatic Morality: Television and Proper Distance, International Journal of Cultural Studies. Frosh, P. & A. Pinchevsky (2009) Why media witnessing? Why now? in Paul Frosh and Amit Pinchevsky, eds., Media Witnessing. Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-19.

18

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Robertson: Narratives of Resistance

Gitlin, T. (1980) The Whole World is Watching. Berkeley: University of California Press. Grusin, R. (2010) Premediation. Affect and mediality after 9/11. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. Hallin, D. C. & P. Mancini (2004) Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hessel, S. (2011) Time for Outrage (Indignez-Vous!). New York: Hachette. Hjarvard, S. (2008) The Mediatization of Society. A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change, Nordicom Review 29(2): 105-134. Hoskins, A. & B. OLoughlin (2010) War and Media. The Emergence of Diffused War. Cambridge and Malden: Polity. Krotz, F. (2009) Mediatization: A concept with which to grasp media and societal change, in Lundby, K. (eds.) Mediatization. Concept, changes, consequences. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 21-40. Lorenzo-Dus, N. & A. Bryan (2011) Recontextualizing participatory journalists mobile media in British television news: A case study of the live coverage and commemorations of the 2005 London bombings, Discourse and Communication 5(1): 23-40. McCarthy, J. et al. (1996) Images of Protest, American Sociological Review 6(3): 478-499. Meyrowitz, J. (1999) No sense of place: the impact of electronic media on social behavior, pp. 99-120 in H. Mackay & T. OSullivan, eds., The media reader: continuity and transformation. London: Open University/Sage. Painter, J. (2008) Counter-Hegemonic News. A Case Study of Al Jazeera English and Telesur. Reuters Institute. Peters, J.D. (2009) Witnessing, in Paul Frosh and Amit Pinchevsky, eds., Media Witnessing. Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23-48.

Published by De Gruyter, 2012

19

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

New Global Studies, Vol. 6 [2012], Iss. 2, Art. 3

Robertson, A. (2012) Connecting in Crisis. Old and new media and the Arab Spring. Paper presented at the panel on Digital Media Power Struggles, ISA 2012. Robertson, A. (2010) Mediated Cosmopolitanism. The World of Television News. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press. Robertson, A. (2008) Cosmopolitanization and Real Time Tragedy: Television News Coverage of the Asian Tsunami, New Global Studies Vol. 2:2, Article 4. Robertson, A. (2005) Journalists, Narratives of European Enlargement and the Man-on-the-Sofa, Statsvetenskapliga Tidskrift 107(3), pp. 235-256. Scannell, P. (2004) What reality has misfortune? Media, Culture & Society Vol. 26(4): 573-584. Seib, P. ed. (2012) Al Jazeera English. Global News in a Changing World. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. Silverstone, R. (2007) Media and Morality: On the Rise of the Mediapolis. Cambridge: Polity. Szerszynski, B. & Urry, J. (2006) Visuality, mobility and the cosmopolitan: inhabiting the world from afar, The British Journal of Sociology Vol. 57(1), pp. 113-131. Usher, N. (2011) How Egypts uprising is helping redefine the idea of a media event, Nieman Journalism Lab, February 8th, http://www.niemanlab.org/2011/02/how-egypts-uprising-is-helping-redefine-theidea-of-a-media-event/, accessed 11/02/09.

20

Brought to you by | East Carolina University Authenticated | 150.216.68.200 Download Date | 11/24/12 2:10 AM

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Webtv ListDocumento72 pagineWebtv ListXhoiZekaj100% (1)

- Doha News Media & Advertising KitDocumento15 pagineDoha News Media & Advertising KitOmar ChatriwalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rania Elwy رانيا علويDocumento5 pagineRania Elwy رانيا علويrania.elwy666Nessuna valutazione finora

- Youmans, William Lafi - An Unlikely Audience - Al Jazeera's Struggle in America (2017, Oxford University Press) - Libgen - LiDocumento257 pagineYoumans, William Lafi - An Unlikely Audience - Al Jazeera's Struggle in America (2017, Oxford University Press) - Libgen - LiOnur GünerNessuna valutazione finora

- The College Hill Independent: April 14, 2011Documento20 pagineThe College Hill Independent: April 14, 2011The College Hill IndependentNessuna valutazione finora

- Al-Jabri 2017Documento247 pagineAl-Jabri 2017Alaa SabbahNessuna valutazione finora

- Discourses of The Veil in Al-Jazeera EnglishDocumento1 paginaDiscourses of The Veil in Al-Jazeera Englishsuem2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Journalists Guide 2013Documento204 pagineJournalists Guide 2013RomeMUN2013Nessuna valutazione finora

- India - Rising Soft PowerDocumento116 pagineIndia - Rising Soft PowerAmit KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Radios Learning EnglishDocumento9 pagineRadios Learning Englishjesus PalliNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Jazeera English Global News in A Changing World (Philip Seib) (Z-Library)Documento211 pagineAl Jazeera English Global News in A Changing World (Philip Seib) (Z-Library)Muhammad S. HameedNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Jazeera English BrochureDocumento11 pagineAl Jazeera English BrochureDel LibroNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparison of CNN International, BBC World News and Al Jazeera English Analysing The Respective Drivers Influencing Editorial ContentDocumento37 pagineA Comparison of CNN International, BBC World News and Al Jazeera English Analysing The Respective Drivers Influencing Editorial ContentCharunivetha SGNessuna valutazione finora

- Lingsat 2Documento37 pagineLingsat 2white hopeNessuna valutazione finora

- Webtv ListDocumento65 pagineWebtv ListIssa GrantNessuna valutazione finora

- Fawzi v. Al JazeeraDocumento22 pagineFawzi v. Al JazeeraTHROnlineNessuna valutazione finora

- Joshy PHD LibraryDocumento309 pagineJoshy PHD LibrarySarvada TaraleNessuna valutazione finora

- Will Trump Run Again and Win?: More From AuthorDocumento6 pagineWill Trump Run Again and Win?: More From AuthorSyed Sulaiman ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Julio Ricardo Varela: ResumeDocumento5 pagineJulio Ricardo Varela: ResumeJulio Ricardo VarelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Jazeera English Wins UN Correspondents Association Foundation PrizeDocumento1 paginaAl Jazeera English Wins UN Correspondents Association Foundation Prizeapi-96680711Nessuna valutazione finora

- Two Faces AlJazeeraDocumento10 pagineTwo Faces AlJazeeraDedee MandrosNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Jazeera As Covered in The Wikileaks CablesDocumento146 pagineAl Jazeera As Covered in The Wikileaks CablesmontagesNessuna valutazione finora

- Youmans Burlington VTDocumento29 pagineYoumans Burlington VTMara KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aljazeera CompleteDocumento7 pagineAljazeera CompleteExpertNessuna valutazione finora

- Eutelsat Programi PDFDocumento113 pagineEutelsat Programi PDFQPI2Nessuna valutazione finora