Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chapter III

Caricato da

Maan EspinosaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chapter III

Caricato da

Maan EspinosaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

THE MUNICIPALITY OF MALABANG, LANAO DEL SUR, et al. vs. PANGANDAPUN BENITO, et al. Facts: 1.

The petitioner Amer Macaorao Balindong is the mayor of Malabang, Lanao del Sur, while the respondent Pangandapun Bonito is the mayor. 2. Balabagan was formerly a part of the municipality of Malabang, having been created on March 15, 1960, by Executive Order 386 of the then President Carlos P. Garcia, out of barrios and sitios of the latter municipality. 3. The petitioners brought this action for prohibition to nullify Executive Order 386 and to restrain the respondent municipal officials from performing the functions of their respective office relying on the ruling of this Court in Pelaez v. Auditor General and Municipality of San Joaquin v. Siva. 4. In Pelaez this Court, through Mr. Justice Concepcion, ruled: a. section 23 of Republic Act 2370 [Barrio Charter Act, approved January 1, 1960], by vesting the power to create barrios in the provincial board, is a "statutory denial of the presidential authority to create a new barrio [and] implies a negation of the bigger power to create municipalities," and b. section 68 of the Administrative Code, insofar as it gives the President the power to create municipalities, is unconstitutional Section 68, as part of the Revised Administrative Code, approved on March 10, 1917, must be deemed repealed by the subsequent adoption of the Constitution, in 1935, which is utterly incompatible and inconsistent with said statutory enactment. 5. Respondents argue that the rule announced in Pelaez can have no application in this case because unlike the municipalities involved in Pelaez, the municipality of Balabagan is at least a de facto corporation a. having been organized under color of a statute before this was declared unconstitutional b. its officers having been either elected or appointed and c. the municipality itself having discharged its corporate functions for the past five years preceding the institution of this action. It is contended that as a de facto corporation, its existence cannot be collaterally attacked, although it may be inquired into directly in an action for quo warranto at the instance of the State and not of an individual like the petitioner Balindong. Issue: WON a statute can lend color of validity to an attempted organization of a municipality despite the fact that such statute is subsequently declared unconstitutional. Held/Ratio: The following principles may be deduced which seem to reconcile the apparently conflicting decisions: I. The color of authority requisite to the organization of a de facto municipal corporation may be: 1. A valid law enacted by the legislature. 2. An unconstitutional law, valid on its face, which has either (a) been upheld for a time by the courts or (b) not yet been declared void; provided that a warrant for its creation can be found in some other valid law or in the recognition of its potential existence by the general laws or constitution of the state. II. There can be no de facto municipal corporation unless either directly or potentially, such a de jure corporation is authorized by some legislative fiat. III. There can be no color of authority in an unconstitutional statute alone, the invalidity of which is apparent on its face. IV. There can be no de facto corporation created to take the place of an existing de jure corporation, as such organization would clearly be a usurper. Hence, in the case at bar, the mere fact that Balabagan was organized at a time when the statute had not been invalidated cannot conceivably make it a de facto corporation, as, independently of the Administrative Code provision in question, there is no other valid statute to give color of authority to its creation. BERGERON v. HOBBS Facts: 1. The defendants, under the name of Bayfield Agricultural Association, employed several persons to perform labor in improving their grounds and in erecting fences and buildings. 2. Time checks given by the defendants to such laborers, for such labor, were assigned to the plaintiff, who brings this action to recover their amount, alleging that the defendants were a copartnership. The defendants alleged that they were members of a corporation, and denied that they were copartners, or liable as such. 3. It appeared upon the trial that articles of organization of the Bayfield County Agricultural Association, and a certificate showing the election of officers, had been recorded in the office of the register of deeds of Bayfield county, but were not on file

there. They had been deposited with instruction to record and return them, which had been complied with. Issues: 1. WON the mere recording of the articles of incorporation, with the certificate of the election of officers, without the intention or fact of the papers themselves remaining in the office, a sufficient compliance with the statute, so that the organization of the corporation became complete, as upon a proper filing of the papers themselves? 2. If the recording was not sufficient for that purpose, are the defendants liable to the plaintiff only as a de facto corporation or as copartners? Held/Ratio: 1. The statute provides that, upon the filing of "a certificate of organization, . . . with a copy of the constitution," in the office of the register of deeds of the county, "such society shall have all the powers of a corporation necessary to promote the objects thereof." It cannot be doubted that the filing of the proper papers in the proper office is made, by the statute, a condition precedent to the vesting of corporate powers. The mere recording and removal of the papers from the office fails to serve the full purpose which the legislature intended to accomplish by the filing of them. A literal filing of the papers is necessary because it is so written in the law. The term "filing" and the verb "to file," as related to this subject, include the idea that the paper is to remain in its proper order on file in the office. A paper is said to be filed when it is delivered to the proper officer, and by him received, to be kept on file. 2. Where an attempt to organize a corporation fails by omission of some substantial step or proceeding required by the statute, its members or stockholders are liable as partners for its acts and contracts. But the defendants' contention is that they are not within this rule, because they are at least de facto a corporation, and their right to be a corporation cannot be inquired into in a collateral action, but only in a direct action for that purpose by the state. In order to secure this immunity from inquiry into its right to be a corporation in a collateral action, its action, as a corporation, must be under a color, at least, of right. It is immaterial that they have carried on business under the supposed authority to act as a body corporate, in entire good faith. If they had not color of legal right, they have obtained no immunity from individual liability for the debts of the supposed corporation. Until the articles of incorporation are filed in the office of the register of deeds of the county, there is no color of legal right to act as a corporation. The filing of such paper is a condition precedent to the right to so act. The defendants are not a corporation either de jure or de facto, but are liable for the plaintiff's claim as partners. It was not necessary to prove a copartnership by evidence. That was established by implication of law. Dissent by Marshall, J. If we adopt the growing doctrine, supported by the overwhelming weight of authority in this country, that if a person contracts with a de facto corporation, the members of the latter and such person believing, in good faith, in its legal existence, such members cannot be held personally liable, then we concede, necessarily, that it is not essential to freedom from such liability that all the statutory requisites to the existence of a corporation be complied with, because, when that is done, the organization, obviously, is not a corporation de facto only; it is a corporation de jure. The very meaning of the term "de facto" indicates that nothing more is necessary to the existence of a de facto corporation than the exercise of corporate powers in good faith. Corporation de facto,--that is, a corporation from the fact that it is acting as such under color of right in good faith. The existence of the law, and some attempt to comply with it, are essential, because without them there can be no assumption of the right to corporate existence in good faith. Persons cannot be said to honestly claim the right to corporate existence, in the absence of any law authorizing the organization, or in the absence of some honest attempt to comply with such law, if one exists. The law and such attempt, or user of the franchise, whatever mistakes may be made in so doing,--such as the filing of articles of organization when they are required to be recorded, or the recording of articles when they are required to be filed, or the filing of such articles in the wrong office, or any other of the numerous mistakes that might be made,--make a corporation good everywhere, in all courts and places, till successfully challenged by the state. From the foregoing, I am warranted in asserting that, by well-settled principles of law, the agricultural association with whom plaintiff contracted was a de facto corporation. Every element necessary to make it such appears clearly by the record. There was a law under which it might have existed.

The association prepared their constitution, and adopted it in the form of ordinary articles of organization, under the general incorporating act, and by mistake they filed it for record, and it was recorded and returned, instead of filing it to be left in the office, as the law requires. They supposed that they had corporate existence by reason of the recording of their articles of organization. They assumed to act as a corporation, and exercised corporate powers for a considerable length of time, and, for aught that appears, in the utmost good faith.

I think the judgment of the circuit court, holding the defendants liable as partners, was wrong, and that it should be reversed, and the cause remanded for a new trial. HARRILL v. DAVIS et al. Facts: 1. Four defendants associated themselves together, and from June 1902 until December 22, 1902, actively engaged in a. purchasing lumber, material, and labor of the plaintiff, and in constructing a cotton gin under the name "The Coweta Gin Company," and b. conducting the business of buying, selling, and ginning cotton for profit under the name "The Coweta Cotton & Milling Company," 2. During this time they incurred more than $4,700 of the indebtedness of $5,145.48 for which this action was brought. 3. On December 22, 1902, they made their first real attempt to incorporate, and for the first time took on the color or appearance of a corporation. On that day they filed articles of incorporation with the clerk of the Court of Appeals, but they never filed any duplicate of them with the clerk of the judicial district in which their place of business was located, as required by the statutes in order to constitute them a legal corporation and to authorize them to do business as such. Issue: WON the defendants formed a corporation de facto and must escape liability. Held/Ratio: I. The burden is not on the strangers who deal with them as a corporation, but on themselves who act under the name of a pretended corporation, to see that it is so organized that it exempts them from individual liability, and if they fail in this they must pay the liabilities they incur, even in the absence of fraud or bad faith. Under the general law of Arkansas in force in the Indian Territory, the filing of articles of incorporation with the clerk of the Court of Appeals was a sine qua non of any color of a legal corporation. Without that there was not, and there could not be, an apparent corporation or the color of a corporation. The defendants cannot escape individual liability for the $4,700 on the ground that the Coweta Cotton & Milling Company was a corporation de facto when that portion of the plaintiff's claim was incurred, because it then had no color of incorporation, and they knew it and yet actively used its name to incur the obligation. II. Another contention is that the defendants are released from liability because the materials and labor for which the $4,700 became due were furnished to them while they were promoting the organization of the corporation for the future corporation, and that the latter has received the benefit of them and ratified their purchase. The rule of law here invoked applies to contracts preliminary and incidental to the organization or to the commencement of the business of a contemplated corporation, and this debt for $4,700 was not the result of any such contract. It is part of the balance of an account which arose out of the conduct of a business preliminary, not to its commencement, but to its close III. Counsel insist that the defendants are not liable here because one who deals with a corporation de facto is estopped from denying its existence as a corporation; but the true meaning and legal effect of this rule is that such a dealer is estopped from denying its existence on the ground that it was not legally incorporated. It is said that the plaintiff is estopped from denying the existence of the defendant's supposed corporation because it was one of its promoters and stockholders, but the evidence fails to convince us. There are two reasons why, under the evidence in this record, the plaintiff never became a holder, either in law or in equity, of any share in the defendant's enterprise or company, either as a stockholder or otherwise. The construction and operation of a cotton gin was beyond the powers of the plaintiff corporation, the nature of whose business was declared and limited by its articles to "buying, selling, leasing and dealing in lands, securities, bonds, notes, stocks and other negotiable paper, and also buying and selling general merchandise." If by any conceivable interpretation the construction and operation of a cotton gin and the formation of the corporation, and the taking of stock therein to accomplish

that purpose, could be deemed to be within the powers of this corporation, they are so far beyond the scope of its ordinary business that a general manager could be authorized to commit his corporation to them only by the express authority of its board of directors, or of its principal officers, after a full disclosure to them of all the facts relating to the proposed enterprise, and the desultory talks which Davis had with the two directors fall far short of any evidence of such authority. C. ARNOLD HALL and BRADLEY P. HALL vs. EDMUNDO S. PICCIO, et al. Facts: 1. Petitioners and the respondents Fred Brown, Emma Brown, Hipolita D. Chapman and Ceferino S. Abella, signed and acknowledged in Leyte, the article of incorporation of the Far Eastern Lumber and Commercial Co., Inc., organized to engage in a general lumber business to carry on as general contractors, operators and managers, etc. 2. Immediately after the execution of said articles of incorporation, the corporation proceeded to do business with the adoption of by-laws and the election of its officers. 3. On December 2, 1947, the said articles of incorporation were filed in the office of the Securities and Exchange Commissioner, for the issuance of the corresponding certificate of incorporation. 4. On March 22, 1948, pending action on the articles of incorporation by the SEC, the respondents filed before the Court of First Instance of Leyte a civil case alleging among other things that the Far Eastern Lumber and Commercial Co. was an unregistered partnership; that they wished to have it dissolved because of bitter dissension among the members, mismanagement and fraud by the managers and heavy financial losses. 5. After hearing the parties, the Hon. Edmund S. Piccio ordered the dissolution of the company; and at the request of plaintiffs, appointed of the properties thereof, upon the filing of a P20,000 bond. 6. Petitioners offered to file a counter-bond for the discharge of the receiver, but the respondent judge refused to accept the offer and to discharge the receiver. Issues: 1. The court had no jurisdiction in the case to decree the dissolution of the company, because it being a de facto corporation, dissolution thereof may only be ordered in a quo warranto proceeding instituted in accordance with section 19 of the Corporation Law. 2. WON there is a corporation or only an unregistered partnership. Held/Ratio: 1. Section 19 reads as follows: The due incorporation of any corporations claiming in good faith to be a corporation under this Act and its right to exercise corporate powers shall not be inquired into collaterally in any private suit to which the corporation may be a party, but such inquiry may be had at the suit of the Insular Government on information of the Attorney-General. There are least two reasons why this section does not govern the situation. Not having obtained the certificate of incorporation, the Far Eastern Lumber and Commercial Co. even its stockholders may not probably claim "in good faith" to be a corporation. Under our statue it is to be noted (Corporation Law, sec. 11) that it is the issuance of a certificate of incorporation by the Director of the Bureau of Commerce and Industry which calls a corporation into being. The immunity if collateral attack is granted to corporations "claiming in good faith to be a corporation under this act." Such a claim is compatible with the existence of errors and irregularities; but not with a total or substantial disregard of the law. This is not a suit in which the corporation is a party. This is litigation between stockholders of the alleged corporation, for the purpose of obtaining its dissolution. Even the existence of a de jure corporation may be terminated in a private suit for its dissolution between stockholders, without the intervention of the state. There might be room for argument on the right of minority stockholders to sue for dissolution; but that question does not affect the court's jurisdiction, and is a matter for decision by the judge, subject to review on appeal. 2. The second proposition may at once be dismissed. All the parties are informed that the Securities and Exchange Commission has not, so far, issued the corresponding certificate of incorporation. All of them know, or sought to know, that the personality of a corporation begins to exist only from the moment such certificate is issued not before (sec. 11, Corporation Law). The Empire Manufacturing Company of Grand Rapids v. William J. Stuart. Facts: 1. The corporation was not properly organized under Michigan law when it executed a promissory note in its corporate name. When it learned that it had not been properly organized, it dissolved, and a new corporation was formed under a different name. The holder brought an action against the corporation to recover on the note.

Issue: WON there is a corporation by estoppel. Held/Ratio: This corporation was one that could have been legally organized under laws existing at the time of its formation. The business for which it was organized, that of manufacturing, was one authorized, and having attempted to organize in good faith, and having, in the course of its business, given negotiable paper in its corporate name, it could not afterwards repudiate the transaction or evade responsibility when sued thereon, by setting up its own mistake, affecting its original organization. The dissolution would not deprive the creditors of still following and looking to the old organization for payment. The statute allows three years after dissolution, for certain purposes, in winding up the affairs. THE LOWELL-WOODWARD HARDWARE COMPANY v. G. R. WOODS et al. Facts: 1. Plaintiff described itself as a Colorado corporation. 2. On appeal, defendant contended that there was no competent evidence of plaintiff's corporate existence, or of defendant's having been a member of the partnership described. 3. A witness for plaintiff testified that it was a corporation, over an objection that the question called for a conclusion, and the ruling was complained of. He said that the plaintiff was running a hardware store; that he inferred it was a corporation from its name and its mode of doing business; and that a bank president had told him it was a corporation. Issue: WON the plaintiff is a corporation. Held/Ratio: One who enters into a written contract with a party described therein as a corporation is precluded, in an action brought thereon by such party under the same designation, from denying its corporate existence. Here the payee was styled in the note, "The LowellWoodward Hardware Company," a title which prima facie imports a corporation. We think it accords with modern views of good practice and tends to promote substantial justice to hold, and we do hold, that one who has signed a promissory note running to a payee described by a name appropriate to a corporation, although not employing that term, cannot, in an action brought against him thereon by such payee under the same name, in which it alleges itself to be a corporation, be heard to question the plaintiff's corporate existence, unless upon a showing that his obligation to make payment would be thereby affected. The defendant, having given his promise to pay the sum indicated to the payee named, should not be permitted to escape or delay performance by raising an issue as to the character of the organization to which he is indebted, unless his substantial rights might be thereby affected, which would only be under exceptional conditions. ASIA BANKING CORPORATION vs. STANDARD PRODUCTS, CO., INC. Facts: 1. The court below rendered judgment in favor of the plaintiff for the sum demanded in the complaint. 2. At the trial of the case the plaintiff failed to prove affirmatively the corporate existence of the parties and the appellant insists that under these circumstances the court erred in finding that the parties were corporations with juridical personality and assigns same as reversible error. Issue: WON the plaintiff is a corporation. Held/Ratio: The general rule is that in the absence of fraud a person who has contracted or otherwise dealt with an association in such a way as to recognize and in effect admit its legal existence as a corporate body is thereby estopped to deny its corporate existence in any action leading out of or involving such contract or dealing, unless its existence is attacked for cause which have arisen since making the contract or other dealing relied on as an estoppel and this applies to foreign as well as to domestic corporations. The defendant having recognized the corporate existence of the plaintiff by making a promissory note in its favor and making partial payments on the same is therefore estopped to deny said plaintiff's corporate existence. It is, of course, also estopped from denying its own corporate existence. CRANSON v. INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION Facts: 1. Cranson was asked to invest in a new business corporation which was about to be created. Towards this purpose he met with other interested individuals and an

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

attorney and agreed to purchase stock and become an officer and director. The business of the new venture was conducted as if it were a corporation, through corporate bank accounts, with auditors maintaining corporate books and records, and under a lease entered into by the corporation for the office from which it operated its business. Cranson was elected president and all transactions conducted by him for the corporation including the dealings with I.B.M., were made as an officer of the corporation. At no time did he assume any personal obligation or pledge his individual credit to I.B.M. Due to an oversight on the part of the attorney, of which Cranson was not aware, the certificate of incorporation, which had been signed and acknowledged prior to May 1, 1961, was not filed until November 24, 1961. Between May 17 and November 8, the Bureau purchased eight typewriters from I.B.M., on account of which partial payments were made, leaving a balance due of $ 4,333.40, for which this suit was brought. On the theory that the Real Estate Service Bureau was neither a de jure nor a de facto corporation and that Albion C. Cranson, Jr., was a partner in the business conducted by the Bureau and as such was personally liable for its debts, the International Business Machines Corporation brought this action against Cranson for the balance due on electric typewriters purchased by the Bureau. In due course, Cranson filed a general issue plea and an affidavit in opposition to summary judgment in which he asserted in effect that the Bureau was a de facto corporation and that he was not personally liable for its debts.

Issue: WON Cranson should be personally liable. Held/Ratio: Since it is clear that the Maryland Tube and National Shutter Bar cases are inconsistent with other Maryland cases insofar as they held that the doctrine of estoppel cannot be invoked unless a corporation has at least a de facto existence, both cases -- Maryland Tube and National Shutter Bar -- should be, and are hereby, overruled to the extent of the inconsistency. Although some cases tend to assimilate the doctrines of incorporation de facto and by estoppel, each is a distinct theory and they are not dependent on one another in their application. Where there is a concurrence of the three elements necessary for the application of the de facto corporation doctrine, there exists an entity which is a corporation de jure against all persons but the state. On the other hand, the estoppel theory is applied only to the facts of each particular case and may be invoked even where there is no corporation de facto. Accordingly, even though one or more of the requisites of a de facto corporation are absent, we think that this factor does not preclude the application of the estoppel doctrine in a proper case, such as the one at bar. We think that I.B.M. having dealt with the Bureau as if it were a corporation and relied on its credit rather than that of Cranson, is estopped to assert that the Bureau was not incorporated at the time the typewriters were purchased.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemDa EverandThe Economic Policies of Alexander Hamilton: Works & Speeches of the Founder of American Financial SystemNessuna valutazione finora

- 27 Scra 533 Municipality of Malabang vs. BenitoDocumento10 pagine27 Scra 533 Municipality of Malabang vs. BenitoRowell SerranoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.pubcorp - Municipality of Malabang Vs Benito DigestDocumento11 pagine1.pubcorp - Municipality of Malabang Vs Benito DigestLucioJr AvergonzadoNessuna valutazione finora

- L. Amores and R. Gonzales For Petitioners. Jose W. Diokno For RespondentsDocumento7 pagineL. Amores and R. Gonzales For Petitioners. Jose W. Diokno For RespondentsLenvic Elicer LesiguesNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion v. de Yriarte, 28 Phil. 67 (1914)Documento4 pagineAsuncion v. de Yriarte, 28 Phil. 67 (1914)inno KalNessuna valutazione finora

- Malabang Vs BenitoDocumento4 pagineMalabang Vs BenitonbandolesNessuna valutazione finora

- Malabang V PangandapunDocumento8 pagineMalabang V Pangandapunherbs22221473Nessuna valutazione finora

- L. Amores and R. Gonzales For Petitioners. Jose W. Diokno For RespondentsDocumento14 pagineL. Amores and R. Gonzales For Petitioners. Jose W. Diokno For RespondentsnikoNessuna valutazione finora

- Malabang v. BenitoDocumento3 pagineMalabang v. BenitoMaria Analyn100% (1)

- 7 Asuncion V de YriarteDocumento4 pagine7 Asuncion V de YriarteanneNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipality of Malabang Vs BenitoDocumento4 pagineMunicipality of Malabang Vs BenitoMargie Booc PajaroNessuna valutazione finora

- 8-Municipality of Malabang v. Benito20181009-5466-1jdedopDocumento8 pagine8-Municipality of Malabang v. Benito20181009-5466-1jdedopmyschNessuna valutazione finora

- MUNICIPALITY OF MALABANG VS. BENITO G.R. No. L-28113Documento6 pagineMUNICIPALITY OF MALABANG VS. BENITO G.R. No. L-28113Bowthen BoocNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion v. de YriarteDocumento4 pagineAsuncion v. de YriarteClement del RosarioNessuna valutazione finora

- C 14 AsuncionDocumento3 pagineC 14 AsuncionKaryl Ann Aquino-CaluyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipality of Malabang V BenitoDocumento3 pagineMunicipality of Malabang V BenitoAweGooseTreeNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation Law Case Digests CompilationDocumento125 pagineCorporation Law Case Digests CompilationRea Jane B. Malcampo100% (3)

- Phil. Trust Co. v. Rivera ruling on capital subscriptionsDocumento10 paginePhil. Trust Co. v. Rivera ruling on capital subscriptionsEdmart VicedoNessuna valutazione finora

- De Facto-De JureDocumento28 pagineDe Facto-De JureLudica Oja100% (2)

- Supreme Court Rules on Corporate Ownership RequirementsDocumento6 pagineSupreme Court Rules on Corporate Ownership RequirementsLenin Rey PolonNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds refusal to register corporationDocumento2 paginePhilippines Supreme Court upholds refusal to register corporationshienalouNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court of the Philippines upholds refusal to register corporation for unlawful purposeDocumento3 pagineSupreme Court of the Philippines upholds refusal to register corporation for unlawful purposeRhoddickMagrataNessuna valutazione finora

- Digested Cases For Corporation LawDocumento4 pagineDigested Cases For Corporation LawNihay Pundato HMNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion Vs de YriarteDocumento3 pagineAsuncion Vs de YriartePhrexilyn PajarilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature and Formation: 1. Definition of A CorporationDocumento109 pagineNature and Formation: 1. Definition of A CorporationBrianCarpioNessuna valutazione finora

- 6-Asuncion Vs YriarteDocumento2 pagine6-Asuncion Vs Yriarteeunice demaclidNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 18 - Section 21Documento46 pagineSection 18 - Section 21AnnJeanetteGuardameNessuna valutazione finora

- FPT - Case Digest Corpo (Riano)Documento30 pagineFPT - Case Digest Corpo (Riano)Pamela DeniseNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 BenitoDocumento9 pagine02 BenitojorementillaNessuna valutazione finora

- So What Is A de Facto Corporation?Documento4 pagineSo What Is A de Facto Corporation?KattNessuna valutazione finora

- Reviewer - Corpo CodeDocumento152 pagineReviewer - Corpo CodeRaina FerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Proper service required to confer jurisdiction over corporationDocumento2 pagineProper service required to confer jurisdiction over corporationisaaabelrfNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion v. de YriarteDocumento3 pagineAsuncion v. de YriarteAira Vanessa CagascasNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo Doctrines (Midterms)Documento19 pagineCorpo Doctrines (Midterms)Cherlene Tan100% (1)

- MUN. OF MALABANG v. BENITODocumento2 pagineMUN. OF MALABANG v. BENITOAliw del Rosario100% (1)

- Corp - Corporate Contract LawDocumento11 pagineCorp - Corporate Contract LawJose Emilio Miclat Teves100% (1)

- Pretest Essay On LawDocumento2 paginePretest Essay On LawHechel DatinguinooNessuna valutazione finora

- CORP Case DigestsDocumento12 pagineCORP Case DigestsFrances Lipnica PabilaneNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE DOCTRINES ON CORPORATIONSDocumento13 pagineCASE DOCTRINES ON CORPORATIONSJaphet C. VillaruelNessuna valutazione finora

- Corp, Set 1, DigestDocumento22 pagineCorp, Set 1, DigestApureelRoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation Law Session 1Documento18 pagineCorporation Law Session 1JessieRealista100% (1)

- Corpo Quiz Week 2 - Answer KeyDocumento6 pagineCorpo Quiz Week 2 - Answer Keyzeigfred badanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Group1 Busorgii Written Report FinalDocumento45 pagineGroup1 Busorgii Written Report FinalPaulo VillarinNessuna valutazione finora

- Loyola Grand Villas Homeowners Association vs CA case digestDocumento22 pagineLoyola Grand Villas Homeowners Association vs CA case digestJu incisoNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Corporation Code ReviewerDocumento19 pagineRevised Corporation Code ReviewerMau BaytingNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporatation Law Doctrines UPDATEDDocumento32 pagineCorporatation Law Doctrines UPDATEDMar Jan GuyNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion Vs de YriarteDocumento2 pagineAsuncion Vs de YriarteKristin De Guzman100% (1)

- Corporation Code - Prelim To BODDocumento183 pagineCorporation Code - Prelim To BODAlfonse100% (1)

- Cases 2 Atty Yen Mendoza 1. Municipality of Malabang vs. Benito (1969)Documento4 pagineCases 2 Atty Yen Mendoza 1. Municipality of Malabang vs. Benito (1969)yenNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo Week 4Documento8 pagineCorpo Week 4Judee AnneNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation Code Notes - Part VDocumento6 pagineCorporation Code Notes - Part VMPLNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipality of Malabang v. BenitoDocumento2 pagineMunicipality of Malabang v. BenitoZoxNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 Vargas and Co V ChanDocumento3 pagine07 Vargas and Co V ChanSantiago TiongcoNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation Law: L. P. IgnacioDocumento27 pagineCorporation Law: L. P. IgnacioAgapito De AsisNessuna valutazione finora

- С ase digest for corporation lawDocumento5 pagineС ase digest for corporation lawBordge BobbieSonNessuna valutazione finora

- Digests 31 - 40Documento16 pagineDigests 31 - 40KarlNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Corporation Code Sections 16-22 SynthesisDocumento5 pagineRevised Corporation Code Sections 16-22 SynthesisAngelica Japitana QuintanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules of Inspection: OCAVA, Regine Victoria G. Corporation Law - 3B Atty. MIP RomeroDocumento4 pagineRules of Inspection: OCAVA, Regine Victoria G. Corporation Law - 3B Atty. MIP RomeroRegine OcavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lim Tong Lim v. Phil. Fishing Gear Industries 317 Scra 728 (1999)Documento9 pagineLim Tong Lim v. Phil. Fishing Gear Industries 317 Scra 728 (1999)FranzMordenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Presidential Decree No. 46Documento1 paginaPresidential Decree No. 46thepocnewsNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re SubidoDocumento21 pagineIn Re SubidoMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nicolas v. RomuloDocumento18 pagineNicolas v. RomuloMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- GSIS V. ChuaDocumento11 pagineGSIS V. ChuaMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. MonleonDocumento6 paginePeople v. MonleonMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. GonzalesDocumento17 paginePeople v. GonzalesMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- University of Pangasinan v. FernandezDocumento19 pagineUniversity of Pangasinan v. FernandezMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- SC Decision on Oakwood Mutiny CasesDocumento21 pagineSC Decision on Oakwood Mutiny CasesMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re SubidoDocumento21 pagineIn Re SubidoMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- US v. RodriguezDocumento3 pagineUS v. RodriguezMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Robbery and Homicide Conviction Upheld for Recidivist OffenderDocumento12 pagineRobbery and Homicide Conviction Upheld for Recidivist OffenderMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise Set 1Documento2 pagineExercise Set 1Maan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- AM No. 03-1-09-SCDocumento9 pagineAM No. 03-1-09-SCJena Mae Yumul100% (7)

- Bengzon v. DrilonDocumento23 pagineBengzon v. DrilonMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- BIR Revenue Regulations No. 2-98Documento93 pagineBIR Revenue Regulations No. 2-98Maan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- BIR Revenue Regulations No. 2-98Documento93 pagineBIR Revenue Regulations No. 2-98Maan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Batas Pambansa BLG 68Documento52 pagineBatas Pambansa BLG 68Maan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus - 2012-13 Civil Procedure (Avena)Documento22 pagineSyllabus - 2012-13 Civil Procedure (Avena)Renz RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Process and Equal Protection OverviewDocumento18 pagineDue Process and Equal Protection OverviewMaan EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Mitchell, 4th Cir. (2002)Documento3 pagineUnited States v. Mitchell, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- BANAT V COMELECDocumento4 pagineBANAT V COMELECloschudentNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023CV382670 - PetitionDocumento23 pagine2023CV382670 - PetitionSean KeenanNessuna valutazione finora

- Temporary InjunctionDocumento20 pagineTemporary InjunctionShayan ZafarNessuna valutazione finora

- SC rules on P213M investment caseDocumento62 pagineSC rules on P213M investment caserenzo zapantaNessuna valutazione finora

- CRPC Presentattion Group QDocumento13 pagineCRPC Presentattion Group QTizoc's KitchenNessuna valutazione finora

- Aviva Security - An Introduction To CCTV Systems LpsDocumento9 pagineAviva Security - An Introduction To CCTV Systems LpsAPHISITH IICTNessuna valutazione finora

- Five J Taxi v. NLRC, 235 Scra 556Documento5 pagineFive J Taxi v. NLRC, 235 Scra 556DNAANessuna valutazione finora

- Juvenile Criminality and Justice Reforms in the USDocumento15 pagineJuvenile Criminality and Justice Reforms in the USChristian Philip VillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociology - U2 M2Documento39 pagineSociology - U2 M2renell simonNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Estafa - People Vs DdavidDocumento11 pagine6 Estafa - People Vs DdavidAtty Richard TenorioNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax Administration Act No 37 of 2018Documento105 pagineTax Administration Act No 37 of 2018Dean KOlthekNessuna valutazione finora

- PublicationDocumento2 paginePublicationcopypoint1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pale-Case Digest-MantillaDocumento4 paginePale-Case Digest-MantillaAnjessette MantillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawyers Format-1Documento2 pagineLawyers Format-1Hart James95% (83)

- Abidin Bin Umar V Doraisamy Anor (1994) 1 MLJ 617Documento7 pagineAbidin Bin Umar V Doraisamy Anor (1994) 1 MLJ 617izzyNessuna valutazione finora

- manual de uso HA16,18PXDocumento74 paginemanual de uso HA16,18PXDaniel Peña VergaraNessuna valutazione finora

- NCDCR Advisory No. 2020-01: National Commission On Discipline and Conflict ResolutionDocumento3 pagineNCDCR Advisory No. 2020-01: National Commission On Discipline and Conflict ResolutionRenvil Igpas MompilNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter Iii ForgeryDocumento7 pagineChapter Iii Forgeryjoshua jacobNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Crime and CorruptionDocumento574 pagineFinancial Crime and CorruptionAbruzzi MariusNessuna valutazione finora

- 127-168 Civ ProDocumento11 pagine127-168 Civ ProJV Dee100% (1)

- Musa G. Mmbaga: Carriculum VitaeDocumento2 pagineMusa G. Mmbaga: Carriculum VitaeInspa SinyinzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 54 Indian Evidence ActDocumento3 pagineSection 54 Indian Evidence Actrejoy singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Art 21. No Felony Shall Be Punishable by Any Penalty Art 22. Penal Laws Shall Have A Retroactive EffectDocumento1 paginaArt 21. No Felony Shall Be Punishable by Any Penalty Art 22. Penal Laws Shall Have A Retroactive EffectNxxxNessuna valutazione finora

- The Law Explained Session 3 Estates, Rolls and RegistersDocumento10 pagineThe Law Explained Session 3 Estates, Rolls and RegistersMinisterNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3 - Reflective Learning DiaryDocumento2 pagineWeek 3 - Reflective Learning DiaryWenyang MingNessuna valutazione finora

- LEA Org Post TestDocumento7 pagineLEA Org Post TestRanier Factor AguilarNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Testimony Learning Guide (CLJ5TES LGDocumento36 pagineCourt Testimony Learning Guide (CLJ5TES LGJustin Benedict Cobacha Macuto100% (1)

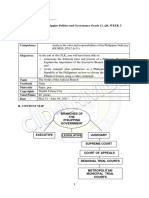

- PolSci Q4 Week 3 - AbellanosaDocumento14 paginePolSci Q4 Week 3 - AbellanosaVergel TorrizoNessuna valutazione finora

- Father Reyes v. CADocumento3 pagineFather Reyes v. CAMCNessuna valutazione finora