Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Fournier Gangrene

Caricato da

Amirah DahalanDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fournier Gangrene

Caricato da

Amirah DahalanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fournier gangrene Background Fournier gangrene was first identified in 1883, when the French venereologist Jean Alfred

Fournier described a series in which 5 previously healthy young men suffered from a rapidly progressive gangrene of the penis and scrotum without apparent cause. This condition, which came to be known as Fournier gangrene, is defined as a polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, perianal, or genital areas (see the image below.) In contrast to Fournier's initial description, the disease is not limited to young people or to males, and a cause is now usually identified.

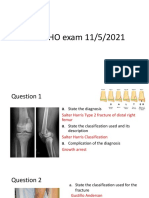

Trauma, Penile Fracture and Urethral Trauma. Historical background

and

Trauma,

In 1764, Baurienne originally described an idiopathic, rapidly progressive soft-tissue necrotizing process that led to gangrene of the male genitalia. However, the disease was named after Jean-Alfred Fournier, a Parisian venereologist, on the basis of a transcript from an 1883 clinical lecture in which Fournier presented a case of perineal gangrene in an otherwise healthy young man, adding this to a compiled series of 4 additional cases.[2] He differentiated these cases from perineal gangrene associated with diabetes, alcoholism, or known urogenital trauma, although these are currently recognized risk factors for the perineal gangrene now associated with his name. This manuscript outlining Fourniers initial series of fulminant perineal gangrene provides a fascinating insight into both the societal background and the practice of medicine at the time. In anecdotes, Fournier described recognized causes of perineal gangrene, including placement of a mistress ring around the phallus, ligation of the prepuce (used in an attempt to control enuresis or as an attempted birth control technique practiced by an adulterous man to avoid impregnating his married lover, placement of foreign bodies such as beans within the urethra, and excessive intercourse in diabetic and alcoholic persons. He calls upon physicians to be steadfast in obtaining confession from patients of obscene practices.

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000X magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD. Impaired immunity (eg, from diabetes) is important for increasing susceptibility to Fournier gangrene. Trauma to the genitalia is a frequently recognized vector for the introduction of bacteria that initiate the infectious process.[1] For more information, see the Medscape Reference articles Testicular Trauma, Scrotal

Anatomy The complex anatomy of the male external genitalia influences the initiation and progression of Fournier gangrene. This infectious process involves the superficial and deep fascial planes of the genitalia. As the microorganisms responsible for the infection multiply, infection spreads along the anatomical fascial planes, often sparing the deep muscular structures and, to variable degrees, the overlying skin. This phenomenon has implications for both initial debridement and subsequent reconstruction. Therefore, a working knowledge of the anatomy of the male lower urinary tract and external genitalia is critical for the clinician treating a patient with Fournier gangrene. Skin and superficial fascia Because Fournier gangrene is predominately an infectious process of the superficial and deep fascial planes, understanding the anatomic relationship of the skin and subcutaneous structures of the perineum and abdominal wall is important. The skin cephalad to the inguinal ligament is backed by Camper fascia, which is a layer of fat-containing tissue of varying thickness and the superficial vessels to the skin that run through it. Scarpa fascia forms another distinct layer deep to Camper fascia. In the perineum, Scarpa fascia blends into Colles fascia (also known as the superficial perineal fascia), while it is continuous with Dartos fascia of the penis and scrotum (see the image below).

Fascial envelopment of the perineum (male). Note how Colles fascia completely envelops the scrotum and penis. Colles fascia is in continuity cephalad to the level of the clavicles. In the inguinal region, this fascial layer is known as Scarpa fascia. Understanding the tendency of necrotizing fasciitis to spread along fascial planes and the fascial anatomy, one can see how a process that starts in the perineum can spread to the abdominal wall, the flank, and even the chest wall. Several important anatomic relationships should be considered. A potential space between the Scarpa fascia and the deep fascia of the anterior wall (external abdominal oblique) allows for the extension of a perineal infection into the anterior abdominal wall. Superiorly, Scarpa and Camper fascia coalesce and attach to the clavicles, ultimately limiting the cephalad extension of an infection that may have originated in the perineum. Colles fascia is attached to the pubic arch and the base of the perineal membrane, and it is continuous with the superficial Dartos fascia of the scrotal wall. The perineal membrane is also known as the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm and, together with Colles fascia, defines the superficial perineal space.

This space contains the membranous urethra, bulbar urethra, and bulbourethral glands. In addition, this space is adjacent to the anterior anal wall and ischiorectal fossae. Infectious disease of the male urethra, bulbourethral glands, perineal structures, or rectum can drain into the superficial perineal space and can extend into the scrotum or into the anterior abdominal wall up to the level of the clavicles. Vascular supply to the skin of the lower abdomen and genitalia Branches from the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries supply the lower aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. Branches of the external and internal pudendal arteries supply the scrotal wall. With the exception of the internal pudendal artery, each of these vessels travels within Camper fascia and can therefore become thrombosed in the progression of Fournier gangrene. Thrombosis jeopardizes the viability of the skin of the anterior scrotum and perineum. Often, the posterior aspect of the scrotal wall supplied by the internal pudendal artery remains viable and can be used in the reconstruction following resolution of the infection. Penis and scrotum The contents of the scrotum, namely the testicles, epididymides, and cord structures, are invested by several fascial layers distinct from the Dartos fascia of the scrotal wall. Again, several important anatomic relationships should be considered. The most superficial layer of the testis and cord is the external spermatic fascia, which is continuous with the external aponeurosis of

the superficial inguinal ring (external abdominal oblique). The next deeper layer is the internal spermatic fascia, which is continuous with the transversalis fascia. A deep fascia termed Buck fascia covers the erectile bodies of the penis, the corpora cavernosa, and the anterior urethra. Buck fascia fuses to the dense tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa, deep in the pelvis. The fascial layers described in this section do not become involved with an infection of the superficial perineal space and can limit the depth of tissue destruction in a necrotizing infection of the genitalia. The corpora cavernosa, urethra, testes, and cord structures are usually spared in Fournier gangrene, while the superficial and deep fascia and the skin are destroyed. Pathophysiology Localized infection adjacent to a portal of entry is the inciting event in the development of Fournier gangrene. Ultimately, an obliterative endarteritis develops, and the ensuing cutaneous and subcutaneous vascular necrosis leads to localized ischemia and further bacterial proliferation. Rates of fascial destruction as high as 2-3 cm/h have been described. Infection of superficial perineal fascia (Colles fascia) may spread to the penis and scrotum via Buck and dartos fascia, or to the anterior abdominal wall via Scarpa fascia, or vice versa. Colles fascia is attached to the perineal body and urogenital diaphragm posteriorly and to the pubic rami laterally, thus limiting progression in these directions. Testicular involvement is rare, as the testicular arteries originate directly from the aorta and thus have a blood supply separate from the affected region.

The following are pathognomonic findings of Fournier gangrene upon pathologic evaluation of involved tissue:

Necrosis of the superficial and deep fascial planes Fibrinoid coagulation of the nutrient arterioles Polymorphonuclear cell infiltration Microorganisms identified within the involved tissues

multiplication.[3] Although Meleney in 1924 attributed the necrotizing infections to streptococcal species only,[4] subsequent clinical series have emphasized the multiorganism nature of most cases of necrotizing infection, including Fournier gangrene.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9] Presently, recovering only streptococcal species is unusual.[10] Rather, streptococcal organisms are cultured along with as many as 5 other organisms. The following are microorganisms:

common

causative

Infection represents an imbalance between (1) host immunity, which is frequently compromised by one or more comorbid systemic processes, and (2) the virulence of the causative microorganisms. The etiologic factors allow the portal for entry of the microorganism into the perineum, the compromised immunity provides a favorable environment to initiate the infection, and the virulence of the microorganism promotes the rapid spread of the disease. See the image below.

Streptococcal species Staphylococcal species Enterobacteriaceae Anaerobic organisms Fungi

Most authorities believe that polymicrobial involvement is necessary to create the synergy of enzyme production that promotes rapid multiplication and spread of Fournier gangrene.[3] For example, one microorganism might produce the enzymes necessary to cause coagulation of the nutrient vessels. Thrombosis of these nutrient vessels reduces local blood supply; thus, tissue oxygen tension falls. The resultant tissue hypoxia allows growth of facultative anaerobes and microaerophilic organisms. These latter microorganisms, in turn, may produce enzymes (eg, lecithinase, collagenase), which lead to digestion of fascial barriers, thus fueling the rapid extension of the infection. Fascial necrosis and digestion are hallmarks of this disease process; this is important to

Necrotizing infection results from infection with an extremely virulent microorganism or, most commonly, from a combination of microorganisms acting synergistically in a susceptible immunocompromised host. Microorganism virulence results from the production of toxins or enzymes that create an environment conducive to rapid microbial

appreciate because it provides the surgeon with a clinical marker of the extent of tissue involvement. Specifically, if the fascial plane can be separated easily from the surrounding tissue by blunt dissection, it is quite likely to be involved with the ischemic-infectious process; therefore, any such dissected tissue should be excised. Far-advanced or fulminant Fournier gangrene can spread from the fascial envelopment of the genitalia throughout the perineum, along the torso, and, occasionally, into the thighs. Etiology Although originally described as idiopathic gangrene of the genitalia, Fournier gangrene has an identifiable cause in 75-95% of cases.[11] The necrotizing process commonly originates from an infection in the anorectum, the urogenital tract, or the skin of the genitalia.[12] Anorectal causes of Fournier gangrene include perianal, perirectal, and ischiorectal abscesses; anal fissures; and colonic perforations. These may be a consequence of colorectal injury or a complication of colorectal malignancy,[13, 14] inflammatory bowel disease,[15] colonic diverticulitis, or appendicitis. Urogenital tract causes include infection in the bulbourethral glands, urethral injury, iatrogenic injury secondary to urethral stricture manipulation, epididymitis, orchitis, or lower urinary tract infection (eg, in patients with long-term indwelling urethral catheters). Dermatologic causes include hidradenitis suppurativa, ulceration due to scrotal pressure, and trauma. Inability to practice

adequate perineal hygiene, such as in paraplegic patients, results in increased risk. Accidental, intentional, or surgical [16] trauma and the presence of foreign bodies may also lead to the disease. The following have been reported in the literature as precipitating factors:

Blunt thoracic trauma Superficial soft-tissue injuries Genital piercings Penile self-injection with cocaine[17] Urethral instrumentation Prosthetic penile implants Intramuscular injections Steroid enemas (used for treatment of radiation proctitis) Rectal foreign body[18] the

In women, septic abortions, vulvar or Bartholin gland abscesses, hysterectomy, and episiotomy are documented sources. In men, anal intercourse may increase risk of perineal infection, either from blunt trauma to the area or by spread of rectally carried microbes. In children, the following have led to the disease:

Circumcision Strangulated inguinal hernia Omphalitis Insect bites Trauma Urethral instrumentation

Perirectal abscesses Systemic infections

Pathogens Wound cultures from patients with Fournier gangrene reveal that it is a polymicrobial infection with an average of 4 isolates per case. Escherichia coli is the predominant aerobe, and Bacteroides is the predominant anaerobe. Other common following:

Malignancy (eg, acute promyelocytic leukemia, acute nonlymphoid leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia)[20, 21] Systemic lupus erythematosus[22] Crohn disease HIV infection[23] Malnutrition Iatrogenic immunosuppression (eg, from long-term corticosteroid therapy) Epidemiology Fournier gangrene is relatively uncommon, but the exact incidence of the disease is unknown. In a review of Fournier gangrene in 1992, Paty and coworkers calculated that approximately 500 cases of the infection have been reported in the literature since Fourniers 1883 report, yielding a prevalence of 1 case in 7500 persons.[24] A retrospective case review revealed 1726 cases documented in the literature from 1950-1999, with an average of 97 cases per year reported from 19891998.[25] Other researchers have reported approximately 600 cases of Fournier gangrene in the world literature since 1996.[26] The frequency of Fournier gangrene has not likely changed appreciably; rather, the apparent increase in the number of cases in the literature most likely results from increased reporting.

microflora

include

the

Proteus Staphylococcus Enterococcus Streptococcus (aerobic and anaerobic) Pseudomonas Klebsiella Clostridium

Predisposition to disease Any condition that depresses cellular immunity may predispose a patient to the development of Fournier gangrene. Examples include the following:

Diabetes mellitus (present in as many as 60% of cases)[19] Morbid obesity Alcoholism Cirrhosis Extremes of age Vascular disease of the pelvis

No seasonal variation occurs. Fournier gangrene is not indigenous to any region of the world, although the largest clinical series originate from the African continent.[27] Sexual and age-related differences in incidence The typical patient with Fournier gangrene is an elderly man in his sixth or seventh decade of life with comorbid diseases. The male-tofemale ratio is approximately 10:1. Lower incidence in females may be caused by better drainage of the perineal region through vaginal secretions. Men who have sex with men may be at higher risk, especially for infections caused by communityassociated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[28] Most reported cases occur in patients aged 30-60 years. A literature review found only 56 pediatric cases, with 66% of those in infants younger than 3 months.

help some patients deal with the emotional stress of an altered body image. If extensive soft tissue is lost, lymphatic drainage may be impaired; thus, dependent edema and cellulitis may result. Use of external support may be beneficial to minimize this postoperative problem. To date, the majority of studies of Fournier gangrene have been retrospective reviews.[29, 30] Therefore, the utility of drawing reliable prognostic information from these studies is very limited. In 1995, Laor and colleagues introduced the Fournier Gangrene Severity Index [31] (FGSI). The FGSI is based on deviation from reference ranges of the following clinical parameters:

Temperature Heart rate Respiratory rate White blood cell count Hematocrit Serum sodium Serum potassium Serum creatinine Serum bicarbonate

Prognosis Large scrotal, perineal, penile, and abdominal wall skin defects may require reconstructive procedures; however, the prognosis for patients following reconstruction for Fournier gangrene is usually good. The scrotum has a remarkable ability to heal and regenerate once the infection and necrosis have subsided. However, approximately 50% of men with penile involvement have pain with erection, often related to genital scarring. Consultation with a psychiatrist may

Each parameter is assigned a score between 0 and 4, with the higher values indicating greater deviation from normal. The FGSI represents the sum of all the parameters values. Laor and colleagues determined that an FGSI greater than 9 correlated with increased

mortality.[31] The FGSI has been validated in several retrospective studies.[32, 33, 34] In 2010, Yilmazlar and colleagues updated the FGSI (UFGSI), adding two additional parameters --age and extent of disease --to further refine the prognostic utility of the FGSI.[35] These 2 groups conclude that the mortality risk in general may be directly proportional to the age of the patient and the extent of disease burden and systemic toxicity upon admission. Factors associated with an improved prognosis include age younger than 60 years, localized clinical disease, absence of systemic toxicity (eg, low FGSI), and sterile blood cultures.[36, 35] Most recently, Roghmann et al queried whether these increasingly complex scoring systems actually outperformed 2 existing and less burdensome morbidity scoring systems, the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (ACCI) and the surgical APGAR score (sAPGAR).[37] They both assessed this retrospectively then prospectively with a 30day follow-up. They noted that ACCI and sAPGAR performed as well as the FGSI and UFGSI and were easier to calculate at the bedside. Again, increasing age and medical comorbidities were associated with increased risk of death.[37] Surprisingly, diabetes and HIV infection are not associated with higher mortality. In some studies, Fournier gangrene that originates from anorectal diseases carries a worse prognosis than cases caused by other factors. The reported mortality rates for Fournier gangrene vary widely, ranging as high as 75%. However, in the 600 cases of Fournier gangrene discovered during a Medline search dating back to 1996, 100 deaths occurred, for

a mortality rate of 16.5%. In the series that included more than 20 patients, the mortality rate ranged from 4-54%, with most studies reporting mortality rates of 20-30%.[38, 39] Factors associated with high mortality include an anorectal source, advanced age, extensive disease (involving abdominal wall or thighs), shock or sepsis at presentation, renal failure, and hepatic dysfunction.[40] Death usually results from systemic illness, such as sepsis (usually gram negative), coagulopathy, acute renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, or multiple organ failure. Fatal tetanus associated with Fournier gangrene has been reported in the literature. History The hallmark of Fournier gangrene is intense pain and tenderness in the genitalia. The clinical course usually progresses through the following phases: 1. Prodromal symptoms of fever and lethargy, which may be present for 27 days 2. Intense genital pain and tenderness that is usually associated with edema of the overlying skin; pruritus may also be present 3. Increasing genital pain and tenderness with progressive erythema of the overlying skin 4. Dusky appearance of the overlying skin; subcutaneous crepitation 5. Obvious gangrene of a portion of the genitalia; purulent drainage from wounds Early in the course of the disease, pain may be out of proportion to physical findings. As

gangrene develops, pain may actually subside as nerve tissue becomes necrotic. Systemic effects of this process vary from local tenderness with no toxicity to florid septic shock. In general, the greater the degree of necrosis, the more profound the systemic effects. Physical Examination The physician should direct particular attention to palpation of the genitalia and perineum and to the digital rectal examination, to assess for signs of the disease and to seek a potential portal of entry. Fluctuance, soft-tissue crepitation, localizing tenderness, or occult wounds in any of these sites should alert the examiner to possible Fournier disease. See image below.

underestimates the degree of underlying disease. A feculent odor may be present secondary to infection with anaerobic bacteria. Crepitus may be present, but its absence does not exclude the presence ofClostridium species or other gas-producing organisms. Systemic symptoms (eg, fever, tachycardia, hypotension) may be present.

DDx

Testicular hematoma Testicular abscess Scrotal abscess Vasculitis Warfarin gangrenosum Polyarteritis nodosum Wegener granulomatosis

Photograph of a morbidly obese male with long-standing phimosis. This condition led to urinary incontinence, perineal diaper rashlike dermatitis, and urinary tract infection. Ultimately, he presented with exquisite perineal pain. An examination with the patient under anesthesia was necessary to discover the necrotizing infection that appeared to originate in the right bulbourethral gland. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD. Skin overlying the affected region may be normal, erythematous, edematous, cyanotic, bronzed, indurated, blistered, and/or frankly gangrenous. Skin appearance often

Differential Diagnoses

Balanitis in Emergency Medicine Cellulitis Emergent Management Epididymitis of Acute

Emergent Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis Gas Gangrene in Emergency Medicine Hernias Hydrocele in Emergency Medicine Orchitis

Testicular Medicine

Torsion

in

Emergency

Approach Considerations Diagnosis of Fournier gangrene is based primarily on clinical findings, and treatment is based on these clinical findings. Incisional biopsy may ultimately confirm the diagnosis. The following studies are indicated:

progresses; and to evaluate for glucose intolerance, which may be due to preexisting diabetes or sepsis-induced metabolic disturbance. Arterial blood gas (ABG) sampling provides a more accurate assessment of acid/base disturbance. Acidosis with hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia may be present. Blood Tests Obtain a CBC to assess the immunologic stress induced by the infectious process, check the adequacy of the red blood cell mass, and evaluate the potential for sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia. A coagulation profile (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, platelet count, fibrinogen level) is helpful to look for sepsis-induced coagulopathy. Blood samples should be drawn for culture to assess for septicemia. Consider type and screen if surgical exploration is undertaken. Plain Radiography Radiography should be considered to evaluate for the presence and extent of Fournier disease, especially when the clinical examination findings are inconclusive.[41, 42] Gas within the soft tissues is detected more commonly with imaging modalities than with the physical examination. (Note that in the setting of a clinical suspicion of Fournier gangrene, demonstration of soft-tissue gas or detection of subcutaneous crepitation is an absolute indication for surgical exploration.) Plain radiography should be the initial imaging study. It may reveal moderate-tolarge amounts of soft-tissue gas, foreign bodies, or scrotal tissue edema. Soft-tissue gas collections (manifest as areas of

Complete blood cell count (CBC) Arterial blood gas (ABG) sampling Blood and urine cultures Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel Cultures of any open wound or abscess

Pelvic imaging studies can be extremely valuable, although sensitivities and specificities of different radiologic modalities are not established. Plain radiography should be the initial imaging study, while computed tomography (CT) should be considered the imaging study of choice. In both cases, the presence of subcutaneous air are very suggestive of the diagnosis in the presence of an appropriate clinical history. In addition, any test deemed necessary to assess exacerbation of a comorbid condition (eg, electrocardiogram and cardiac enzyme evaluation in patients with coronary artery disease) is warranted. Chemistry Panel and Blood Gases Perform a chemistry panel to evaluate possible electrolyte disturbances; to look for laboratory evidence of dehydration (elevated blood urea nitrogen [BUN]/creatinine ratio), which tends to occur as the disease

hyperlucency) may be evident on radiography before they become clinically apparent. However, absence of air on plain films does not exclude the diagnosis. Computed Tomography CT scanning is readily available in most hospitals and should be considered the imaging study of choice, as it defines the extent of the disease more specifically than plain films or ultrasound. CT scanning can reveal smaller amounts of soft-tissue gas than plain radiography and can demonstrate fluid collections that track along the deep fascial planes.[43, 44] Findings include soft-tissue and fascial thickening, fat stranding, and soft-tissue gas collections. CT scan often identifies the underlying cause of the infection (eg, perirectal abscess). The findings may assist in surgical planning. Ultrasonography Ultrasonography can be used to detect fluid or gas within the soft tissues.[45] Gas in the scrotal wall is the "sonographic hallmark" of Fournier gangrene. Air may be appreciated in perineal and/or perirectal areas. Scrotal wall edema may be seen. Testes and epididymides are usually normal. Ultrasonography may reveal other causes of acute scrotal pain, including intratesticular injury, scrotal cellulitis, epididymo-orchitis, testicular torsion, and inguinal hernia. The drawback of ultrasonography is the need for direct pressure on the involved tissue; patients with Fournier gangrene probably will not be able to tolerate this procedure. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Use of MRI in Fournier gangrene is not well described in the literature. MRI yields greater soft tissue detail than does CT scanning; however, MRI requires greater time, with limited ability for patient monitoring during testing. These logistical challenges, which are not shared by CT scanning, limit the practical usefulness of MRI, especially in patients with critical illness. Use of MRI should not delay operative intervention if the diagnosis is highly suspected. Biopsy An incisional biopsy at the time of surgical debridement allows pathological distinction of Fournier gangrene (ie, necrotizing infection) from severe cellulitis. The former would benefit from excisional debridement, while the latter rarely requires surgical excision. The biopsy sample should be taken from the point of maximal tenderness, and it should include skin and superficial and deep fascia. This sample may be sent for frozen-section analysis to assess for fascial necrosis. Early fascial involvement may appear as edematous fascia on gross inspection but may appear as frank necrosis on microscopic analysis. Histologic Findings Pathologic evaluation of the involved tissue may reveal the following pathognomonic findings of Fournier gangrene:

Necrosis of the superficial and deep fascial planes Fibrinoid thrombosis of the nutrient arterioles Polymorphonuclear cell infiltration

Microorganisms identified within the involved tissues

Fibrinoid thrombosis of the nutrient vessels that supply the superficial and deep fascia is the finding that most commonly indicates Fournier disease. Widespread necrosis of the fascia with acute inflammatory cell infiltration and necrotic debris is frequently evident, as is the presence of causative microorganisms within the tissues. This extensive inflammatory process is frequently present deep to intact skin. The skin itself is often minimally involved with the inflammatory process until late in the disease. Approach Considerations Treatment of Fournier gangrene involves several modalities. Surgery is necessary for definitive diagnosis and excision of necrotic tissue. Earlier surgical intervention has been associated with reduced mortality.[46] In patients who present with systemic toxicity manifesting as hypoperfusion or organ failure, aggressive resuscitation to restore normal organ perfusion and function must take precedence over diagnostic maneuvers, especially if these diagnostic studies could compromise the resuscitative interventions. Thus, the emergency department (ED) treatment of patients with Fournier gangrene includes aggressive resuscitation in anticipation of surgery. Provide airway management if indicated, give supplemental oxygen, and establish intravenous (IV) access and continuous cardiac monitoring. Crystalloid replacement is indicated for patients who are dehydrated or displaying signs of shock.

Early, broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated. Tetanus prophylaxis is indicated if soft-tissue injury is present. In addition, any underlying comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes, alcoholism) must ultimately be addressed. Such conditions are common in these patients, and potentially predispose to Fournier gangrene. Failure to adequately manage the comorbid conditions may threaten the success of even the most appropriate interventions to resolve the infectious disease. Antibiotic and Antifungal Therapy Treatment of Fournier gangrene involves the institution of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. The antibiotic spectrum should cover staphylococci, streptococci, the Enterobacteriaceae family of organisms, and anaerobes. A reasonable empiric regimen might consist of ciprofloxacin and clindamycin. Clindamycin is particularly useful in the treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections because of its gram-positive and anaerobic spectrum of activity. In animal models of streptococcal infection, clindamycin has been shown to yield response rates superior to those of penicillin or erythromycin, even in the context of delayed treatment.[47] Other possible choices include ampicillin/sulbactam, ticarcillin/clavulanate, or piperacillin/tazobactam in combination with an aminoglycoside and metronidazole or clindamycin. Vancomycin can be used to provide coverage for methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In cases associated with sepsis syndrome, therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), which is thought to neutralize

superantigens (eg, streptotoxins A and B) believed to mitigate the exaggerated cytokine response, has been shown to be a good adjuvant to appropriate antibiotic coverage and complete surgical debridement.[48] If initial tissue stains (ie, potassium hydroxide [KOH] stain) show fungi, add an empiric antifungal agent such as amphotericin B or caspofungin. Surgical Diagnosis and Debridement In the event of a presumptive diagnosis based on a clinical examination or diagnostic study, the definitive diagnosis of Fournier gangrene is provided by examination with the patient under anesthesia followed by incision into the area of greatest clinical concern. If frankly gangrenous tissue is found or purulence is drained, the diagnosis of Fournier gangrene is established. See image below.

gangrene. In this instance, obtain an incisional biopsy sample of the deep fascia for frozen-section evaluation to exclude early necrotizing disease. Excising necrotic tissue Once a diagnosis of Fournier gangrene is established, all necrotic tissue must be excised. In a large retrospective review of 379 patients, Sugihara et al confirmed the opinion that early surgical intervention reduces mortality. Those who underwent earlier intervention had a lower fatality rate (odds ratio, 0.38) than those whose intervention was delayed to 3 days or later.[46] The skin should be opened widely to expose the full extent of the underlying fascial and subcutaneous tissue necrosis. All fascial planes that separate easily with blunt dissection should be considered involved and therefore excised. The dissection should be carried out to include bleeding tissues (ie, tissue that is well vascularized). Send samples of excised tissue for aerobic and anaerobic cultures and a histologic assessment.

In a man with alcoholism and known cirrhosis who presented with exquisite pain limited to the scrotum, opening of the scrotum along the median raphe liberated foul-smelling brown purulence and exposed necrotic tissue throughout the mid scrotum. The testicles were not involved. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD. Occasionally, early-stage Fournier disease manifests as severe cellulitis. If an incision is made, the fascia may appear edematous rather than exhibiting the gray-black appearance of well-established Fournier

Given the characteristic thrombosis of the nutrient vessels, the overlying skin has impaired blood supply and should be excised if significantly undermined. The authors strongly recommend radical excisional debridement (see below image) with electrocautery in order to reduce the considerable operative blood loss if the area of involvement is extensive.

Local skin flap coverage Split-thickness skin grafts Muscular flaps, which are used to fill a cavity (eg, ischiorectal space)

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Patient with Fournier gangrene following radical debridement. A dorsal slit was made in the prepuce to expose the glans penis. Urethral catheterization was performed. Incision into the point of maximal tenderness on the right side of the perineum revealed gangrenous necrosis that involved the anterior and posterior aspects of the perineum, the entirety of the right hemiscrotum, and the posterior medial aspect of the right thigh. The skin and involved fascia were excised from these areas. Reconstruction of this defect was performed in a staged approach. A gracilis rotational muscle flap taken from the right thigh was used to fill the cavity in the posterior right perineum as the first step. The remainder of the defect was covered with split-thickness skin grafts. This patient made a full recovery. The testicles are often spared in the necrotizing process. If it is uninvolved, place the exposed testicle in a subcutaneous pocket to prevent desiccation. If a testicle is involved in the necrotic process or its viability is questioned, performorchiectomy. Reconstruction Once the infection is eradicated, healthy granulation tissue develops; this signifies the time to proceed to reconstruction. Options for following:

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) has been used as an adjuvant to surgical and antimicrobial therapy. Indications include failure of conventional treatment, documented clostridial involvement, or myonecrosis or deep tissue involvement. HBO is postulated to reduce systemic toxicity, prevent extension of necrotizing infection, and inhibit growth of anaerobic bacteria. HBO has shown some promising results.[51, 52, 53] However, in one series, there was actually a trend toward increased mortality in patients undergoing HBO,[54]although this trend may have been related to selection bias. The role of HBO in the treatment of Fournier disease needs to be clarified with a prospective controlled trial.[54] Decisions regarding HBO must be made on an individual basis, taking into consideration the stability of the patient. Use of HBO must not delay surgical debridement. Investigational Treatments The role of topical agents in wound care requires further investigation. Unprocessed honey, applied directly to the surface of the wounds, has been reported by some authors to enzymatically debride, sterilize, and dehydrate wounds and to improve local tissue oxygenation and re-epithelialization. However, the salutatory effect of honey is likely related to its physical property of hyperosmolarity.[55] Therefore, honey holds

reconstruction

include

the

Primary closure of the skin, if possible

little advantage over other hygroscopic agents.[56] The application of growth hormones and other trophic agents holds the potential to promote faster wound healing. One published case report advocates irrigation of the perineum with superoxidized water as well as application of gauze soaked in zinc peroxide and hydrogen peroxide. Transfer Fournier gangrene is a true surgical emergency. At minimum, immediate urologic or general surgical consultation is mandatory, and management often requires a multidisciplinary team, including a urologist, a general surgeon, and an intensive care specialist. Transfer to a tertiary facility may be required if these resources are not available at the initial facility. Initial debridement may be performed if required in anticipation of transfer. Arrange for transfer once the patient has been stabilized and resuscitative efforts have begun.

Class Summary Initiate early broad-spectrum antibiotics as soon as possible. Providing coverage for gram-positive, gram-negative, aerobic, and anaerobic bacteria is essential. Penicillins and beta-lactamase inhibitors or triple antibiotics are potential choices. Vancomycin (Vancocin) Vancomycin is a potent antibiotic directed against gram-positive organisms and active against enterococcal species. It is useful for the treatment of septicemia and skin structure infections. Vancomycin is indicated for patients who cannot receive or have failed to respond to penicillins and cephalosporins or for those who have infections with resistant staphylococci. For abdominal penetrating injuries, combine with an agent active against enteric flora and/or anaerobes. To avoid toxicity, assay of vancomycin trough levels after the third dose drawn 0.5 h prior to next dosing currently is recommended. Dose adjustment may be necessary in patients with renal impairment; follow creatinine clearance (CrCl). Ampicillin-sulbactam sodium (Unasyn) This is a drug combination that uses a betalactamase inhibitor with ampicillin; covers skin, enteric flora, and anaerobes; not ideal for nosocomial pathogens. Ticarcillin and (Timentin) clavulanate potassium

This antipseudomonal penicillin plus betalactamase inhibitor provides coverage against most gram-positive and gram-negative organisms and most anaerobes. It contains

4.7-5 mEq of sodium per gram. Ticarcillin inhibits biosynthesis of bacterial cell wall mucopeptide and is effective during the active growth stage. Piperacillin and tazobactam (Zosyn) This combination of an antipseudomonal penicillin and a beta-lactamase inhibitor inhibits biosynthesis of bacterial cell wall mucopeptide and is effective during the stage of active multiplication. Gentamicin An aminoglycoside antibiotic used for gramnegative bacterial coverage, gentamicin is commonly used in combination with both an agent against gram-positive organisms and one that covers anaerobes. Consider using gentamicin when penicillins or other less toxic drugs are contraindicated, when bacterial susceptibility tests and clinical judgment indicate use, and in mixed infections caused by susceptible strains of staphylococci and gram-negative organisms. Dosing regimens are numerous and are adjusted on the basis of CrCl and changes in the volume of distribution. Gentamicin may be administered IV or IM. Metronidazole (Flagyl) Metronidazole is an imidazole ring-based antibiotic that is active against anaerobes. It is usually given in combination with other antimicrobial agents, except when used for Clostridium difficile enterocolitis, in which case monotherapy is appropriate. Metronidazole is active against various anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. It appears to be absorbed into cells of microorganisms that contain nitroreductase; then, unstable intermediate compounds are formed that

bind DNA and inhibit synthesis, causing cell death. Clindamycin (Cleocin) Clindamycin is a lincosamide useful in treatment against serious skin and soft-tissue infections caused by most staphylococci strains; it is also effective against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, except enterococci. This agent inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by inhibiting peptide chain initiation at the bacterial ribosome, where it preferentially binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit, causing bacterial growth inhibition. Immunizations Class Summary Fatal tetanus associated with Fournier gangrene has been documented in the literature. Patients with noncurrent tetanus status require immunization in the emergency department. Diphtheria and tetanus toxoid (Decavac) Tetanus toxoid is manufactured by first culturing Clostridium tetani and then detoxifying the toxin with formaldehyde. This toxoid commonly is combined with diphtheria toxoid, and both serve to induce production of serum antibodies to toxins produced by the bacteria.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Papillary CarcinomaDocumento7 paginePapillary Carcinomarazik89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Surgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ADocumento14 pagineSurgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ATwinkle SalongaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dermoid CystDocumento8 pagineDermoid CystMohamed Hazem ElfollNessuna valutazione finora

- BENIGN OVARIAN DISEASES - Updated January 2018Documento31 pagineBENIGN OVARIAN DISEASES - Updated January 2018daniel100% (1)

- Ewing SarcomaDocumento4 pagineEwing SarcomaNurulAqilahZulkifliNessuna valutazione finora

- 40 Phimosis 1Documento8 pagine40 Phimosis 1Navis Naldo AndreanNessuna valutazione finora

- EndometriosisDocumento46 pagineEndometriosisManoj Ranadive0% (1)

- OMCDocumento37 pagineOMCyurie_ameliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Necrotizing FasciitisDocumento7 pagineNecrotizing FasciitisjoycefrancielleNessuna valutazione finora

- Fournier's Gangrene: Dr. Vinod JainDocumento28 pagineFournier's Gangrene: Dr. Vinod JainAulia Rahma NoviastutiNessuna valutazione finora

- Inguinal HerniaDocumento9 pagineInguinal HerniaAmanda RapaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wilms TumorDocumento12 pagineWilms TumorKath CamachoNessuna valutazione finora

- Testicular TorsionDocumento20 pagineTesticular TorsionDarshan SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Ranula Cyst, (Salivary Cyst) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDa EverandRanula Cyst, (Salivary Cyst) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ectopic PregnancyDocumento46 pagineEctopic PregnancyNoegi AkasNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Assessment: Patient History, An Infant or A Child May Be Relatively Free From Symptom Until She or He CriesDocumento4 pagineNursing Assessment: Patient History, An Infant or A Child May Be Relatively Free From Symptom Until She or He Criescyrilcarinan100% (1)

- Testicular TorsionDocumento20 pagineTesticular TorsionGAURAV100% (3)

- Penile CancerDocumento18 paginePenile CancerSmiley QueenNessuna valutazione finora

- Inguinal HerniaDocumento27 pagineInguinal HerniaNeneng WulandariNessuna valutazione finora

- Phyllodes Tumors of The Breast FINALDocumento25 paginePhyllodes Tumors of The Breast FINALchinnnababuNessuna valutazione finora

- Hiatal Hernia: BY MR, Vinay KumarDocumento27 pagineHiatal Hernia: BY MR, Vinay KumarVinay KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Penetrating Abdominal TraumaDocumento67 paginePenetrating Abdominal TraumarizkaNessuna valutazione finora

- Endometrial Polyps: Irregular Menstrual BleedingDocumento4 pagineEndometrial Polyps: Irregular Menstrual BleedingLuke ObusanNessuna valutazione finora

- Type of IncisionsDocumento5 pagineType of IncisionsChelzea ObarNessuna valutazione finora

- #Disease of External EarDocumento4 pagine#Disease of External EarameerabestNessuna valutazione finora

- Penile Cancer 2010Documento28 paginePenile Cancer 2010raghavagummadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Endocrine NeoplasiaDocumento4 pagineMultiple Endocrine NeoplasiaDivya RanasariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)Documento37 pagineOral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)Yusra Shaukat100% (1)

- Abdominal Wall DefectsDocumento16 pagineAbdominal Wall DefectsDesta FransiscaNessuna valutazione finora

- Inguinal Hernias: CaseDocumento6 pagineInguinal Hernias: Casechomz14Nessuna valutazione finora

- ADENOMYOSISDocumento5 pagineADENOMYOSISdoddydrNessuna valutazione finora

- Umibilical Cord - ProlapsDocumento22 pagineUmibilical Cord - ProlapsAtikah PurnamasariNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (Men1)Documento19 pagineMultiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (Men1)Sukma LiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Examination of Salivary GlandsDocumento29 pagineExamination of Salivary GlandsSamchristy MammenNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Emergency Skills in Trauma Part 3 - Penetrating Abdoninal Injury - Dr. Oliver BelarmaDocumento3 pagineBasic Emergency Skills in Trauma Part 3 - Penetrating Abdoninal Injury - Dr. Oliver BelarmaRaquel ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Malunion Delayed Union and Nonunion FracturesDocumento31 pagineMalunion Delayed Union and Nonunion FracturesRasjad ChairuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric Surgery Dr. A. IgamaDocumento6 paginePediatric Surgery Dr. A. IgamaMarco Paulo Reyes NaoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study CA Lower RectumDocumento47 pagineCase Study CA Lower RectumArtyom Granovskiy100% (1)

- HerniaDocumento11 pagineHerniaHapsari Wibawani 'winda'100% (1)

- Peritonitis: Presentan: FAUZAN AKBAR YUSYAHADI - 12100118191Documento21 paginePeritonitis: Presentan: FAUZAN AKBAR YUSYAHADI - 12100118191Fauzan Fourro100% (1)

- Pathology of Female Genital System, 2024Documento63 paginePathology of Female Genital System, 2024Eslam HamadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hernia Examination OSCE GuideDocumento7 pagineHernia Examination OSCE GuideEssa AfridiNessuna valutazione finora

- Trichiasis: Prepared By:pooja Adhikari Roll No.: 27 SMTCDocumento27 pagineTrichiasis: Prepared By:pooja Adhikari Roll No.: 27 SMTCsushma shresthaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFDocumento4 pagine2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFteteh_thikeuNessuna valutazione finora

- Infertilty 2Documento9 pagineInfertilty 2Kristine VanzuelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Imperforate Anus: Preoperative CareDocumento2 pagineImperforate Anus: Preoperative CareLalisaM ActivityNessuna valutazione finora

- Pregnancy Uterus Fetus Embryo: Morbidity Selectively Reduce Multiple PregnancyDocumento4 paginePregnancy Uterus Fetus Embryo: Morbidity Selectively Reduce Multiple Pregnancynyzgirl17Nessuna valutazione finora

- Endometriosis - Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocumento39 pagineEndometriosis - Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis - UpToDatefujimeisterNessuna valutazione finora

- Sweet Syndrome EnglishDocumento19 pagineSweet Syndrome EnglishAsma AlwiNessuna valutazione finora

- Vulva CancerDocumento2 pagineVulva CancerLim Hui ZhuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Peritonsillar AbscessDocumento1 paginaPeritonsillar AbscessFatimah Az-ZahrahNessuna valutazione finora

- Fistula in AnoDocumento21 pagineFistula in AnoHannah LeiNessuna valutazione finora

- TonsilitisDocumento32 pagineTonsilitisFitriNajibahNessuna valutazione finora

- RhabdomyosarcomaDocumento12 pagineRhabdomyosarcomaAnonymous 8QktfX9sZ6Nessuna valutazione finora

- Stevens-Johnson SyndromeDocumento13 pagineStevens-Johnson SyndromeJoyce Blancaflor LoganNessuna valutazione finora

- Ewing SarcomaDocumento15 pagineEwing Sarcomaamel015Nessuna valutazione finora

- ENT Benign Neck MassesDocumento2 pagineENT Benign Neck MassesLucyellowOttemoesoeNessuna valutazione finora

- UlcersDocumento2 pagineUlcersAamir BugtiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ovarian CancerDocumento15 pagineOvarian CancerAlmasNessuna valutazione finora

- Cellulitis and Skin AbscessDocumento18 pagineCellulitis and Skin AbscessAnonymous ZUaUz1wwNessuna valutazione finora

- Skin and Soft Tissue Infection InfoDocumento4 pagineSkin and Soft Tissue Infection InfoPresura Andreea IulianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cellulitis: Clinical Review: Be The First To CommentDocumento9 pagineCellulitis: Clinical Review: Be The First To CommentAnonymous 1nMTZWmzNessuna valutazione finora

- Wound Infection Following Repair of Abdominal Wall HerniaDocumento13 pagineWound Infection Following Repair of Abdominal Wall HerniadadupipaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gross & Ghastly - Human BodyDocumento130 pagineGross & Ghastly - Human BodyShubham PriyamNessuna valutazione finora

- Skin and Eye Infection MicpDocumento17 pagineSkin and Eye Infection MicpMarc Kevin MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 Skin and Wound Infections - StudentDocumento35 pagine2013 Skin and Wound Infections - Studentmicroperadeniya0% (1)

- Necrotizing FasciitisDocumento5 pagineNecrotizing Fasciitisnsl1225Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final English 211c Part ADocumento4 pagineFinal English 211c Part Aapi-341958041Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bacterial Infections of Skin-ClassificationDocumento26 pagineBacterial Infections of Skin-ClassificationSajin AlexanderNessuna valutazione finora

- Ortho HO Exam NS AnswerDocumento33 pagineOrtho HO Exam NS Answersarvesswara muniandyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tom Skin-Sparing Approach To Treatemen of NSTI 2016Documento14 pagineTom Skin-Sparing Approach To Treatemen of NSTI 2016Sadaf Raisa KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Infectious DiseasesDocumento11 pagineTypes of Infectious DiseasesmaricelNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacteriology (Heba)Documento176 pagineBacteriology (Heba)irs531997Nessuna valutazione finora

- Phoenix Journal #175Documento120 paginePhoenix Journal #175GustavBlitzNessuna valutazione finora

- Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections: Anna Norrby-Teglund Mattias Svensson Steinar Skrede EditorsDocumento212 pagineNecrotizing Soft Tissue Infections: Anna Norrby-Teglund Mattias Svensson Steinar Skrede EditorsPpds Mikro UI 2019Nessuna valutazione finora

- Necrotizing FasciitisDocumento14 pagineNecrotizing FasciitisZied TrikiNessuna valutazione finora

- 45 Necrotising FasciitisDocumento17 pagine45 Necrotising FasciitisJasna MeenangadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Microbiology of Mus Culo Skeletal InfectionsDocumento12 pagineMicrobiology of Mus Culo Skeletal InfectionsgegelviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis TopicsDocumento14 pagineThesis TopicskiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Wounds and Tissue RepairDocumento4 pagineWounds and Tissue RepairMuhammad Mohsin Ali Dynamo0% (1)

- Surgery 8th Semester McqsDocumento24 pagineSurgery 8th Semester McqsarbazNessuna valutazione finora

- Boushra Rahman Postpartum InfectionDocumento1 paginaBoushra Rahman Postpartum InfectionClinica GinecologicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 1 - PuerperiumDocumento66 pagineSession 1 - PuerperiumCHALIE MEQUNessuna valutazione finora

- Fournier's Gangrene. A Clinical ReviewDocumento9 pagineFournier's Gangrene. A Clinical ReviewJohannes MarpaungNessuna valutazione finora

- A Case Report of Hemolytic Streptococcal Gangrene in The Danger Triangle of The Face With Thrombocytopenia and HepatitisDocumento5 pagineA Case Report of Hemolytic Streptococcal Gangrene in The Danger Triangle of The Face With Thrombocytopenia and HepatitisKimberly Liseth Mora FrancoNessuna valutazione finora

- SSTIDocumento64 pagineSSTIDigafe TolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 6 SpondyloarthropathiesDocumento124 pagineWeek 6 SpondyloarthropathiesJoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Repair of Vaginal and Perineal Tears22Documento4 pagineRepair of Vaginal and Perineal Tears22Francez Anne GuanzonNessuna valutazione finora

- S1 Revision by Hania KhanDocumento87 pagineS1 Revision by Hania KhanZoha AzizNessuna valutazione finora