Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cross Culture Management in IKEA

Caricato da

Samson RodriguesCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cross Culture Management in IKEA

Caricato da

Samson RodriguesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

According to jackson(2002:18) 'cultural differesnces should be taken into acccount when communicating and interacting across nations and

across cultures within nations'. Discuss the impact of cultural differences on organisational communication; making specfic reference to the information supplied concerning IKEA's approach to communicating with employees in different local and national cultures.

Cross-Cultural Management: The IKEA Approach

Aristotle observed over two millennia ago the differences he saw in cultures of people residing in warm climates, who he described as intelligent but not very heroic, as opposed to inhabitants of cold climates, who he in turn called brave but not so intelligent. Since then much more detailed analysis by various researchers has led to the formation of many different theories and models regarding the differences in culture. These differences can be noticed (or not) in national cultures, family cultures, company cultures, and functional cultures (i.e. sales versus marketing). In an ever-increasing global environment these differences are more and more becoming daily issues that need to be addressed in order for multinational organizations to carry on with their operations. IKEA is a typical example of a growing multinational which has expanded their operations into different national markets. They sell furniture along with part of their culture; their blue and yellow image is becoming recognizable throughout the world. IKEA pays close attention to the cultures of the countries that they have expanded into, especially when considering their employees in that foreign market. It is their intention to bring their values with them wherever they open up stores and this calls for a fundamental understanding of the different cross-cultural theories that have been developed by

individuals such as Edward T. Hall, Geert Hofstede, Fons Trompenaars et al; a due diligence phase of cultural analysis. With this careful analysis in hand, strategies on how to approach the different culture must be developed and then implemented. This essay will attempt to discuss some of the different cross-cultural approaches, while keeping IKEAs cross-cultural management of their operations in Spain as the fundamental measure of theory being put into practice. Hofstede and his four dimensions theory should be mentioned first because even though his theory was not the first on the topic, in some direct or indirect way he has influenced the theories of those that followed him. The four dimensions are power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, and uncertainty avoidance. Nations are analyzed through questionnaires and then ranked with a score - which is then determined as high, medium, low or any variation in between. Hofstede believed that, to have valid findings, you must have a constant organizational culture and then study that culture in different nations. The basic notion of power distance is how a given society deals with inequality. Thus a high score on the PDI (Power Distance Index) reflects a culture within a nation that supports inequalities amongst its citizens (or employees), whereas a low score demonstrates the inverse - inequalities are not tolerated well. In a high PD culture you will find privileged power holders, a need for hierarchy, acceptance of inequality, high dependence needs of the employees, and, due to the entrenchment of power holders and acceptance of others, change comes by revolution. Remove those in power and replace them with others and maintain the same acceptance of inequality. On the other hand, low PD cultures have hierarchy for convenience, equal rights for everyone, superiors are more

accessible, there is low dependence needs and, in these cultures, changes come by evolution. Sweden has traditionally a low PD score (31), while Spain has a mid to high score of (57). It is said that when the Swedes gave the throne to a Frenchman in 1809, their newly-crowned king was laughed at by the citizens (commoners included) after delivering an acceptance speech in poorly-pronounced Swedish. This wasnt considered disrespectful because the people didnt see a huge gap of power between themselves and the King, such as would have been found in many other countries where such behaviour was unheard of, for example the Kings homeland of France, Spain and the rest of the Mediterranean, where there definately was then, and is now, a distinction between superior and inferior positions in society. Power distance beliefs do not really change much over time in a country according to Hofstede. Another aspect that is worth touching on is the four leadership styles that relate to PDI scores. The first is the tells style. This is found in extremely high PDI cultures, where leaders make decisions and then announce them to subordinates. Next, we have the sells style found in mid to high PDI cultures; here we find leaders making decisions and then trying to convince subordinates that they are good ones. Third we have the consults style found in mid to low cultures, where leaders get input from subordinates before making a decision. Finally, we have the delegates style in extremely low cultures. Leaders allow subordinates to make their own decisions - of course within some predetermined limits. Sweden should be more of a delegates/consults culture, whereas Spain would be classified as more of a sells/consults culture. There is a significant difference between the two but it is not a massive divide that cannot be accounted for and strategically met. In an individualistic society, people are expected to take care of themselves and

their immediate family. These are I cultures. At the opposite end of the spectrum are collective societies, the WE cultures. In-groups, formed early on and kept throughout ones life, consist of extended family, friends, and even business associates. Protection is given to the member by these groups in return for loyalty. Failure in an individualistic society brings on feelings of guilt and a loss of self respect; tasks are valued over relationships. In a collective society relationships are valued over tasks, and members avoid losing face. Private and work lives are combined in these collective cultures and are separated in individualistic cultures. The individualists tend to believe that the rules should apply universally to everyone, while collectivists are particular about how the rules should apply, reserving more favourable treatment for members of their in-group. Nepotism and favouritism are frequently found in collective societies, and many multinationals with operations in these countries adopt anti-nepotism policies which employees are expected to sign. Sweden is more individualistic then Spain with their IND scores being (71) and (51) respectively. Sweden scores the lowest in masculinity with a score of (5), making it the most feminine culture tested. This has no real direct relation to gender other than the longenduring belief that qualities such as caring for others, quality of life, and solidarity are found predominately in women. On the opposite end, masculine societies supposedly place more value on achievement, success and competition. Spain has a low to mid score of (42). Work goals tend to be focused in this way in these different cultures. Masculine cultures place highest emphasis on earnings potential, followed by recognition, the opportunity for advancement, and the feeling of challenge and accomplishment. On the Feminine cultures end of the spectrum, the most important aspects at work are to have a

good working relationship with ones supervisor, cooperation with peers, live in a desirable area, and have a sense of real job security. Sweden and Spain diverge here and these differences must be considered when attempting to motivate employees. The last of the four dimensions is uncertainty avoidance. High scores reflect low trust cultures which tend to have a need to avoid failure, seek consensus, are fearful of conflict, create many rules and laws, and tend to exhibit high stress and anxiety levels. People in these cultures are prone to displaying emotions in public and they are considered expressive societies. Non-expressive societies are the cultures that score low on the UA index. They are cultures that are willing to take more risks, believe that conflicts are fair play, have less laws and rules, accept dissent, and appear more relaxed and stress free. This relaxed nature is betrayed by the fact that they are prone to excessive drinking in order to express emotions and they suffer higher rates of heart attack compared with the expressive cultures. Spain has an extremely high score of (86) and Sweden has a relatively low score of (29). This was a direct issue with IKEAs informality and unconventional solutions being poorly accepted by the Spanish, forcing IKEA to introduce more structure to meet the natural inclinations of their new employees. They recruited a Spanish HR manager to better understand what was expected.

The theory of high context versus low context cultures was developed by Edward T. Hall. The three most important aspects that this distinction determines in a cultures beliefs are communication styles, proxemics (the notion of interpersonal space), and time. First the differences regarding communication. High context cultures place a high emphasis on non-verbal cues such as status and position; communication is implicit, and

agreements are more spoken than written. In a low context culture, messages must be explicit, agreements must be written, and status and non-verbal cues tend to be questioned, which is rare in high context cultures. Asian countries tend to be high context cultures, highly dependent on implicit status and cues and concerned with the avoidance of loss of face. Spain is placed somewhere in the middle between high and low and Sweden is placed as a very low context culture (Business Horizons, May-June 1993, Figure 3, p.72). The next area to review is the cultures dissenting view on proxemics, or how much interpersonal space is necessary between people. This is a very important issue. For example, many Arab cultures, which are high context, believe that during a conversation you should feel the breath and sometimes even the saliva of the person you are talking to to feel connected. This is in total contradiction to the belief of the Scandinavians (low context) who tend to feel more at ease when conversing with a metre or more buffer zone between the conversing parties. This plays an important role during cross-cultural business meetings and especially at more informal functions. Here many low context individuals may find individuals from high context to be pushy and aggressive, always closing the distance during conversations. The inverse may be felt by the high context individual who might believe that people from low context cultures are distant and cold, always pulling away and being non-committal. The Spanish would prefer interaction to take place under a metre and the Swedes at a metre plus. Yet this slight adjustment shouldnt pose any real problems for IKEA management - when in Rome The last aspect of concern is the views on the concept of time by these two different cultures. High context cultures are known to be polychromic, doing more than

one thing at a time, less concerned with promptness, and allow human transactions to take precedent over keeping schedule (I got caught up with another appointment being an adequate excuse for missing another). Low context cultures are considered monochromic. They tend to finish one thing at a time before moving on to the next; are concerned with promptness, and break time into small units to maximize efficiency. Once again Spain tends to be just slightly on the polychromic side - not as concerned with schedules and time. Even though IKEA (Sweden) has an informal, loose method regarding structure (uncertainty avoidance), they are more monochromic and basically follow time and appointments more closely than the Spanish.

Fons Trompenaars said culture was like an onion - basically consisting of three layers; the observable outer layer, the middle layer or values and norms layer, and the inner core layer. The outer layer is what we primarily associate with the culture - the clothing, food, visual behaviour and language and, within an organization, their organizational charts, handbook of HR policies, etc. The second layer reflects what norms and values an organization or a nation holds, norms representing what they judge as right or wrong, values reflecting what is good and what is bad. Finally, the inner layer, the core of the culture, is difficult for outsiders to detect. It is the unquestioned implicit culture that is built-in, and is the hardest to change. A good example of this is the Japanese culture of bowing. Understanding this core culture is essential to working within different cultures. According to Trompenaars, the specific culture must be recognized and respected. In conclusion, IKEAs move into the Spanish market is helped significantly by

their Swedish culture. Although there are distinct cultural differences, the consensusseeking nature of the Swedish culture allows for an easier transition. The adoption of a more structured management approach is a good example of this. IKEA set out at the onset to create a harmonious transfer of ideas, culture and expectations, not only to the Spanish but from the Spanish to Swedish managers as well. The seminars to foster discussion between both sides are a good way to reduce personnel turnover due to frustration. It allows for a forum where employees can express their discontent as well as their personal expectations. Another well-planned move was the initiative to have 80% of the management roles taken up by Spanish managers. This allows for a grass-roots understanding of the culture by those in decision-making positions, who could in turn share knowledge with their Swedish colleagues. These managers first undergo training in the IKEA culture, so they should be best prepared to strike a balance with IKEAs expectations, as well as those of their domestic employees.

Bibliography: Fons Trompenaars and Peter Woolliams: When Two Worlds Collide. (Trompenaars Hampden-Turner 2000)

BJ Punnett and S. Withane (1990) Adapted from Hofstedes Value Survey Module: To Embrace or Abandon? Advances in International Comparative Management. ( Greenwich, CT: JAI Press

R. Hill (1995) We Europeans. Brussels: Europublications

A C Bluedorn, C.F. Kaufman, and P.M. Lane (1992) How Many Things Do You Like to Do at Once? An Introduction to Monochronic and Polychronic Time? Academy of Management Executive

Chakravarthy and Perimutter (1985) Strategic Planning for a Global Business. New York: Columbia Journal of World Business

Hofstede, G (1994) Cultures and Organisations: Intercultural Co-operation and its Importance for Survival. London: Harper Collins Adler N.J. (1997), International Dimensions of Organizational Behaviour. Ohio: South-

Western College Publishing

Hofstede, G (1980) Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values. Beverly Hills CA: Sage Publications

Mead, R. (2000) International Management: Oxford: Blackwell Rugman, A.M. & Hodgets R.M. (1995) International Business: A Strategic Management Approach. New York: McGraw-Hill

Warner, M. & Joynt P. (2002) Managing Across Cultures: Issues and Perspectives. London: Thomson Learning

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Greaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160Documento3 pagineGreaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160ajd.nanthakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To BioArbitrageDocumento31 pagineIntroduction To BioArbitrageHarrison HayesNessuna valutazione finora

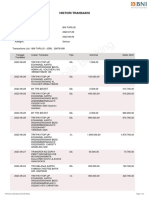

- Histori TransaksiDocumento3 pagineHistori TransaksiIyan SiwuNessuna valutazione finora

- Junior Lawyer Resume PDF Free Download PDFDocumento3 pagineJunior Lawyer Resume PDF Free Download PDFAnubhav PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Jinny ClaimDocumento49 pagineJinny ClaimTutor Seri KembanganNessuna valutazione finora

- PVRDocumento9 paginePVRSovid GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentasi Ak. Keu. KLMPK 3Documento14 paginePresentasi Ak. Keu. KLMPK 3Menaz Sadaka100% (1)

- Tax 2 Digest (0406) GR 108576 012099 Cir Vs CaDocumento3 pagineTax 2 Digest (0406) GR 108576 012099 Cir Vs CaAudrey Deguzman100% (1)

- Horizontal Balance Sheet: Total Equity&LiabilitiesDocumento7 pagineHorizontal Balance Sheet: Total Equity&LiabilitiesM.TalhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bayawan City Investment Code 2011Documento12 pagineBayawan City Investment Code 2011edwardtorredaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011-2012 Quebec BudgetDocumento524 pagine2011-2012 Quebec BudgetGlobal_Montreal100% (1)

- 2012 DMO Unified System of AccountsDocumento30 pagine2012 DMO Unified System of AccountshungrynicetiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 5Documento19 pagineWeek 5Darryl GoodwinNessuna valutazione finora

- Functions of Ecgc and Exim BankDocumento12 pagineFunctions of Ecgc and Exim BankbhumishahNessuna valutazione finora

- Abstract On Budgetary ControlDocumento22 pagineAbstract On Budgetary ControlIhab Hosny AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Go - 6255 2Documento1 paginaGo - 6255 2Priyank PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- GOvernance Test QuestionsDocumento1 paginaGOvernance Test QuestionsChristine Leal100% (1)

- Final Case Study 0506Documento25 pagineFinal Case Study 0506Namit Nahar67% (3)

- TAXATION Agriculture IncomeDocumento7 pagineTAXATION Agriculture IncomeLalitadityaLalitNessuna valutazione finora

- Aregay Editd ProposalDocumento25 pagineAregay Editd ProposalFasiko AsmaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ias 16 Property Plant and Equipment SummaryDocumento8 pagineIas 16 Property Plant and Equipment SummaryFelice FeliceNessuna valutazione finora

- Gokarna Forest Resort: Salary SlipDocumento7 pagineGokarna Forest Resort: Salary SlipPradip ShahiNessuna valutazione finora

- Can The Developers Move For Specific Performance of The Development Agreement?Documento6 pagineCan The Developers Move For Specific Performance of The Development Agreement?Manas Ranjan SamantarayNessuna valutazione finora

- Soniya BegDocumento124 pagineSoniya BegRibhanshu RajNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Updated NEC3 ECC Cable Spreading Contract MPMAT10069GXDocumento49 pagineRevised Updated NEC3 ECC Cable Spreading Contract MPMAT10069GXAaron MulopeNessuna valutazione finora

- Approved Scale of Finance 2019-20Documento7 pagineApproved Scale of Finance 2019-20Kamal SainiNessuna valutazione finora

- Modigliani MillerDocumento12 pagineModigliani MillerAlvaro CamañoNessuna valutazione finora

- TraderEdge - Backtesting BlueprintDocumento12 pagineTraderEdge - Backtesting BlueprintPaulo TuppyNessuna valutazione finora

- Parmalat ScandalDocumento5 pagineParmalat ScandalshakilnaimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Exchange: Satvik, Vrisshin, ManyaaDocumento48 pagineForeign Exchange: Satvik, Vrisshin, ManyaaAditya VernNessuna valutazione finora