Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Hydrogen Atom

Caricato da

Elyasse B.Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Hydrogen Atom

Caricato da

Elyasse B.Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Hydrogen atom

Hydrogen atom

Hydrogen-1

Full table General Name, symbol Neutrons Protons protium, 1H 0 1 Nuclide data Natural abundance 99.985% Half-life Isotope mass Spin Excess energy Binding energy Stable 1.007825u + 7,288.9690.001keV 00keV

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral atom contains a single positively charged proton and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb force. Atomic hydrogen constitutes about 75% of the elemental mass of the universe.[1] (Most of the universe's mass is not in the form of chemical elementsthat is, "baryonic" matterbut is made up of dark matter and dark energy.) In everyday life on Earth, isolated hydrogen atoms (usually called "atomic hydrogen" or, more precisely, "monatomic hydrogen") are extremely rare. Instead, hydrogen tends to combine with other atoms in compounds, or with itself to form ordinary (diatomic) Depiction of a hydrogen atom showing the diameter as about twice the Bohr model radius. (Image not to scale) hydrogen gas, H2. "Atomic hydrogen" and "hydrogen atom" in ordinary English use have overlapping meanings. For example, a water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms, but does not contain atomic hydrogen (which would refer to isolated hydrogen atoms).

Hydrogen atom

Production and reactivity

The HH bond is one of the toughest bonds in chemistry, with a bond dissociation enthalpy of 435.88kJ/mol at 298 K (25C; 77F). As a consequence of this strong bond, H2 dissociates to only a minor extent until higher temperatures. At 3,000 K (2,730C; 4,940F), the degree of dissociation is just 7.85%:[2] H2 2 H Hydrogen atoms are so reactive that they combine with almost all elements.

Isotopes

The most abundant isotope, hydrogen-1, protium, or light hydrogen, contains no neutrons; other isotopes of hydrogen, such as deuterium or tritium, contain one or more neutrons. The formulas below are valid for all three isotopes of hydrogen, but slightly different values of the Rydberg constant (correction formula given below) must be used for each hydrogen isotope.

Quantum theoretical analysis

The hydrogen atom has special significance in quantum mechanics and quantum field theory as a simple two-body problem physical system which has yielded many simple analytical solutions in closed-form. In 1913, Niels Bohr obtained the spectral frequencies of the hydrogen atom after making a number of simplifying assumptions. These assumptions, the cornerstones of the Bohr model, were not fully correct but did yield the correct energy answers. Bohr's results for the frequencies and underlying energy values were confirmed by the full quantum-mechanical analysis which uses the Schrdinger equation, as was shown in 19251926. The solution to the Schrdinger equation for hydrogen is analytical. From this, the hydrogen energy levels and thus the frequencies of the hydrogen spectral lines can be calculated. The solution of the Schrdinger equation goes much further than the Bohr model, because it also yields the shape of the electron's wave function ("orbital") for the various possible quantum-mechanical states, thus explaining the anisotropic character of atomic bonds. The Schrdinger equation also applies to more complicated atoms and molecules. In most such cases the solution is not analytical and either computer calculations are necessary or simplifying assumptions must be made.

Solution of Schrdinger equation: Overview of results

The solution of the Schrdinger equation (wave equations) for the hydrogen atom uses the fact that the Coulomb potential produced by the nucleus is isotropic (it is radially symmetric in space and only depends on the distance to the nucleus). Although the resulting energy eigenfunctions (the orbitals) are not necessarily isotropic themselves, their dependence on the angular coordinates follows completely generally from this isotropy of the underlying potential: the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (that is, the energy eigenstates) can be chosen as simultaneous eigenstates of the angular momentum operator. This corresponds to the fact that angular momentum is conserved in the orbital motion of the electron around the nucleus. Therefore, the energy eigenstates may be classified by two angular momentum quantum numbers, and m (both are integers). The angular momentum quantum number = 0, 1, 2, ... determines the magnitude of the angular momentum. The magnetic quantum number m = , ..., + determines the projection of the angular momentum on the (arbitrarily chosen) z-axis. In addition to mathematical expressions for total angular momentum and angular momentum projection of wavefunctions, an expression for the radial dependence of the wave functions must be found. It is only here that the details of the 1/r Coulomb potential enter (leading to Laguerre polynomials in r). This leads to a third quantum number, the principal quantum number n = 1, 2, 3, .... The principal quantum number in hydrogen is related to the atom's total energy.

Hydrogen atom Note that the maximum value of the angular momentum quantum number is limited by the principal quantum number: it can run only up to n 1, i.e. = 0, 1, ..., n 1. Due to angular momentum conservation, states of the same but different m have the same energy (this holds for all problems with rotational symmetry). In addition, for the hydrogen atom, states of the same n but different are also degenerate (i.e. they have the same energy). However, this is a specific property of hydrogen and is no longer true for more complicated atoms which have a (effective) potential differing from the form 1/r (due to the presence of the inner electrons shielding the nucleus potential). Taking into account the spin of the electron adds a last quantum number, the projection of the electron's spin angular momentum along the z-axis, which can take on two values. Therefore, any eigenstate of the electron in the hydrogen atom is described fully by four quantum numbers. According to the usual rules of quantum mechanics, the actual state of the electron may be any superposition of these states. This explains also why the choice of z-axis for the directional quantization of the angular momentum vector is immaterial: an orbital of given and m obtained for another preferred axis z can always be represented as a suitable superposition of the various states of different m (but same l) that have been obtained for z.

Alternatives to the Schrdinger theory

In the language of Heisenberg's matrix mechanics, the hydrogen atom was first solved by Wolfgang Pauli[3] using a rotational symmetry in four dimension [O(4)-symmetry] generated by the angular momentum and the LaplaceRungeLenz vector. By extending the symmetry group O(4) to the dynamical group O(4,2), the entire spectrum and all transitions were embedded in a single irreducible group representation.[4] In 1979 the (non relativistic) hydrogen atom was solved for the first time within Feynman's path integral formulation of quantum mechanics.[5][6] This work greatly extended the range of applicability of Feynman's method.

Mathematical summary of eigenstates of hydrogen atom

Energy levels The energy levels of hydrogen, including fine structure, are given by the Sommerfeld expression:

where is the fine-structure constant and j is a number (eigenvalue) that represents the total angular momentum, which is equal to 1/2 depending on the direction of the electron spin. The factor in square brackets in the last expression is nearly one; the extra term arises from relativistic effects (for details, see #Features going beyond the Schrdinger solution). The value

is called the Rydberg constant and was first found from the Bohr model as given by

Hydrogen atom

where me is the electron mass, e is the elementary charge, h is the Planck constant, and 0 is the vacuum permittivity. This constant is often used in atomic physics in the form of the Rydberg unit of energy:

[7]

The exact value of the Rydberg constant above assumes that the nucleus is infinitely massive with respect to the electron. For hydrogen-1, hydrogen-2 (deuterium), and hydrogen-3 (tritium) the constant must be slightly modified to use the reduced mass of the system, rather than simply the mass of the electron. However, since the nucleus is much heavier than the electron, the values are nearly the same. The Rydberg constant RM for a hydrogen atom (one electron), R is given by: quantity where M is the mass of the atomic nucleus. For hydrogen-1, the

is about 1/1836 (i.e. the electron-to-proton mass ratio). For deuterium and tritium, the ratios are

about 1/3670 and 1/5497 respectively. These figures, when added to 1 in the denominator, represent very small corrections in the value of R, and thus only small corrections to all energy levels in corresponding hydrogen isotopes. Wavefunction The normalized position wavefunctions, given in spherical coordinates are:

where: , is the Bohr radius, is a generalized Laguerre polynomial of degree n 1, and is a spherical harmonic function of degree and order m. Note that the generalized Laguerre polynomials are defined differently by different authors. The usage here is consistent with the definitions used by Messiah,[8] and Mathematica.[9] In other places, the Laguerre polynomial includes a factor of ,[10] or the generalized Laguerre polynomial appearing in the hydrogen wave function is instead. [11] The quantum numbers can take the following values:

3D illustration of the eigenstate

Electrons in this state are 45% likely to be found within the solid body shown.

Additionally, these wavefunctions are normalized (i.e., the integral of their modulus square equals 1) and orthogonal:

where function.

[12]

is the representation of the wavefunction

in Dirac notation, and

is the Kronecker delta

Hydrogen atom Angular momentum The eigenvalues for Angular momentum operator:

Visualizing the hydrogen electron orbitals

The image to the right shows the first few hydrogen atom orbitals (energy eigenfunctions). These are cross-sections of the probability density that are color-coded (black represents zero density and white represents the highest density). The angular momentum (orbital) quantum number is denoted in each column, using the usual spectroscopic letter code (s means =0, p means =1, d means =2). The main (principal) quantum number n (= 1, 2, 3, ...) is marked to the right of each row. For all pictures the magnetic quantum number m has been set to 0, and the cross-sectional plane is the xz-plane (z is the vertical axis). The probability density in three-dimensional space is obtained by rotating the one shown here around the z-axis. The "ground state", i.e. the state of lowest energy, in which the electron is usually found, is the first one, the 1s state (principal quantum level n = 1, = 0).

Probability densities through the xz-plane for the electron at different quantum numbers (, across top; n, down side; m = 0)

An image with more orbitals is also available (up to higher numbers n and ). Black lines occur in each but the first orbital: these are the nodes of the wavefunction, i.e. where the probability density is zero. (More precisely, the nodes are spherical harmonics that appear as a result of solving Schrdinger's equation in polar coordinates.) The quantum numbers determine the layout of these nodes.[13] There are: total nodes, of which are angular nodes: angular nodes go around the

cross-sections through the xz-plane.)

axis (in the xy plane). (The figure above does not show these nodes since it plots

(the remaining angular nodes) occur on the (vertical) axis. (the remaining non-angular nodes) are radial nodes.

Features going beyond the Schrdinger solution

There are several important effects that are neglected by the Schrdinger equation and which are responsible for certain small but measurable deviations of the real spectral lines from the predicted ones: Although the mean speed of the electron in hydrogen is only 1/137th of the speed of light, many modern experiments are sufficiently precise that a complete theoretical explanation requires a fully relativistic treatment of the problem. A relativistic treatment results in a momentum increase of about 1 part in 37,000 for the electron. Since the electron's wavelength is determined by its momentum, orbitals containing higher speed electrons show contraction due to smaller wavelengths. Even when there is no external magnetic field, in the inertial frame of the moving electron, the electromagnetic field of the nucleus has a magnetic component. The spin of the electron has an associated magnetic moment which interacts with this magnetic field. This effect is also explained by special relativity, and it leads to the so-called spin-orbit coupling, i.e., an interaction between the electron's orbital motion around the nucleus, and its

Hydrogen atom spin. Both of these features (and more) are incorporated in the relativistic Dirac equation, with predictions that come still closer to experiment. Again the Dirac equation may be solved analytically in the special case of a two-body system, such as the hydrogen atom. The resulting solution quantum states now must be classified by the total angular momentum number j (arising through the coupling between electron spin and orbital angular momentum). States of the same j and the same n are still degenerate. There are always vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, according to quantum mechanics. Due to such fluctuations degeneracy between states of the same j but different l is lifted, giving them slightly different energies. This has been demonstrated in the famous Lamb-Retherford experiment and was the starting point for the development of the theory of Quantum electrodynamics (which is able to deal with these vacuum fluctuations and employs the famous Feynman diagrams for approximations using perturbation theory). This effect is now called Lamb shift. For these developments, it was essential that the solution of the Dirac equation for the hydrogen atom could be worked out exactly, such that any experimentally observed deviation had to be taken seriously as a signal of failure of the theory. Due to the high precision of the theory also very high precision for the experiments is needed, which utilize a frequency comb. Hydrogen ion Hydrogen is not found without its electron in ordinary chemistry (room temperatures and pressures), as ionized hydrogen is highly chemically reactive. When ionized hydrogen is written as "H+" as in the solvation of classical acids such as hydrochloric acid, the hydronium ion, H3O+, is meant, not a literal ionized single hydrogen atom. In that case, the acid transfers the proton to H2O to form H3O+. Ionized hydrogen without its electron, or free protons, are common in the interstellar medium, and solar wind.

References

[2] Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4. [7] P.J. Mohr, B.N. Taylor, and D.B. Newell (2011), "The 2010 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" (Web Version 6.0). This database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. Available: http:/ / physics. nist. gov/ constants. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899. Link to R (http:/ / physics. nist. gov/ cgi-bin/ cuu/ Value?ryd), Link to hcR (http:/ / physics. nist. gov/ cgi-bin/ cuu/ Value?rydhcev) [9] LaguerreL (http:/ / reference. wolfram. com/ mathematica/ ref/ LaguerreL. html). Wolfram Mathematica page [12] Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, Griffiths 4.89 [13] Summary of atomic quantum numbers (http:/ / www. physics. byu. edu/ faculty/ durfee/ courses/ Summer2009/ physics222/ AtomicQuantumNumbers. pdf). Lecture notes. 28 July 2006

Books

Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Prentice Hall. ISBN0-13-111892-7. Section 4.2 deals with the hydrogen atom specifically, but all of Chapter 4 is relevant. Bransden, B.H.; C.J. Joachain (1983). Physics of Atoms and Molecules. Longman. ISBN0-582-44401-2 tacos. Kleinert, H. (2009). Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, 4th edition, Worldscibooks.com (http://www.worldscibooks.com/physics/7305.html), World Scientific, Singapore (also available online physik.fu-berlin.de (http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/re.html#B8))

Hydrogen atom

External links

Physics of hydrogen atom on Scienceworld (http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/physics/HydrogenAtom.html) Interactive graphical representation of orbitals (http://webphysics.davidson.edu/faculty/dmb/hydrogen/) Applet which allows viewing of all sorts of hydrogenic orbitals (http://www.falstad.com/qmatom/) The Hydrogen Atom: Wave Functions, and Probability Density "pictures" (http://panda.unm.edu/Courses/ Finley/P262/Hydrogen/WaveFcns.html) Basic Quantum Mechanics of the Hydrogen Atom (http://www.physics.drexel.edu/~tim/open/hydrofin) "Research team takes image of hydrogen atom" Kyodo News, Friday, 5 November 2010 (includes image) (http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20101105a1.html)

Lighter: hydrogen atom is an Heavier: (none, lightest possible) isotope of hydrogen hydrogen-2 Decay product of: neutronium-1 helium-2 Decay chain of hydrogen atom Decays to: Stable

Article Sources and Contributors

Article Sources and Contributors

Hydrogen atom Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=557369724 Contributors: 1exec1, 28bytes, 2over0, 777sms, A. di M., A876, Adamrubin, Addshore, AhmedHan, Ahoerstemeier, Akriasas, Antandrus, Anthony Appleyard, Anville, Aquilosion, Army1987, Arnero, Art LaPella, Aschwole, Ashill, AstroNomer, Barbara Shack, BenRG, Bensaccount, BernardH, Bevo, Bgamari, Bkkbrad, BlahBlah1122, BlazerKnight, Bloopblop, Bobrayner, Bogey97, Borowsky, Brandonrush, Brownsteve, Bryan Derksen, CYD, Catdogqq, Catgut, Cenarium, Chairman S., Characteru, Charles Matthews, Chris the speller, Christopher.Gordon3, Ciaccona, Cometstyles, Complexica, Conversion script, Craig Pemberton, Cricobr, CuriousEric, Dainis, Dangermouse29, DarkCatalyst, Dchristle, Discospinster, Donarreiskoffer, Donotresus, Double sharp, Dr-er, Drilnoth, Droidus, Dugosz, Eackad, Ebehn, Edsanville, Ehrenkater, Eio, Essjay, Extra999, Flies 1, FlorianMarquardt, Freakofnurture, Freiddie, Geek1337, Gene Nygaard, Geniac, Giftlite, Glenn, Glosser.ca, Gmeiner, Gogobera, GregRM, Guillom, Guitarstud101, Hadal, HansM, HappyCamper, HavikRyan, Headbomb, Homestarmy, IRWolfie-, Icairns, Incnis Mrsi, InverseHypercube, Invitamia, J.delanoy, JWB, JabberWok, Jaganath, Jared Hunt, Joanjoc, Johanna faust, John, John C PI, John254, JorisvS, Josemiotto, Jsalazar, Juro2351, Karol Langner, Keenan Pepper, Kevin Cowtan, Kevmitch, Kickstart70, Kingpin13, KonradG, Korua, Linas, Lincher, Lotje, Lottamiata, Marek69, Mark viking, Materialscientist, MathKnight, Mathieu Perrin, Maurice Carbonaro, Melchoir, Metarhyme, Micah.prange, Michael Hardy, Mike40033, Mion, Mlouns, MuDavid, NeonMerlin, Nezzadar, Nilmerg, Njmatulich, Nk, Northfox, Oo64eva, Paine Ellsworth, Parra22, Passw0rd, Pathfinder, Pfalstad, PhiberOptik, Picodeoro, Pinethicket, Pjacobi, Postscript07, Pyfan, Prez, Ququ, RDBury, RDLWIK, Rangek, Res2216firestar, Rgamble, Riana, Rmashhadi, RoB, Robbin' Knowledge, Ronhjones, Rorro, Rory096, RoyGoldsmith, Rursus, Sango123, Sbharris, Seaphoto, SeventyThree, Shadowjams, Sheridan Zhoy, Sikory, Siqamar, Skanaar, Smokefoot, Southen, Srleffler, Stephenedie, StewartMH, Stoive, Svick, TUT2006, Tgeairn, The Anome, The way, the truth, and the light, Thomas.fernholz, Thurth, Tide rolls, Tim Starling, Timothyduignan, Timwi, Tpbradbury, Trojancowboy, Ummit, Valodzka, Vanished User 0001, Vaughan Pratt, Vegetator, Vexedd, Vortexrealm, Vsmith, Vsst, WAS 4.250, Wapcaplet, Wayiran, Wayne Slam, WhiteHatLurker, Whoop whoop pull up, Wtmitchell, XJaM, Xanderk84, Yill577, Zginder, Zmcdargh, Zueignung, Zzuuzz, 302 anonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors

Image:Hydrogen 1.svg Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Hydrogen_1.svg License: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Contributors: Hydrogen-1.png: User:Joanjoc derivative work: Gregors (talk) 13:57, 17 March 2011 (UTC) File:hydrogen atom.svg Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Hydrogen_atom.svg License: Public Domain Contributors: Bensaccount Image:Hydrogen eigenstate n4 l3 m1.png Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Hydrogen_eigenstate_n4_l3_m1.png License: Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Contributors: Geek3 File:HAtomOrbitals.png Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:HAtomOrbitals.png License: GNU Free Documentation License Contributors: Admrboltz, Benjah-bmm27, Dbc334, Dbenbenn, Ejdzej, Falcorian, Hongsy, Kborland, MichaelDiederich, Mion, Saperaud, 6 anonymous edits

License

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Gravitational Waves and Spacetime - Mario BungeDocumento5 pagineGravitational Waves and Spacetime - Mario BungethemechanixNessuna valutazione finora

- Nuclear Spectroscopy and Reactions 40-ADa EverandNuclear Spectroscopy and Reactions 40-AJoseph CernyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gravitational WavesDocumento15 pagineGravitational WavesSourabh PrakashNessuna valutazione finora

- Nuclear Spectroscopy and Reactions 40-DDa EverandNuclear Spectroscopy and Reactions 40-DJoseph CernyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gravitational Waves: Einstein's Legacy: Vinod KumarDocumento4 pagineGravitational Waves: Einstein's Legacy: Vinod KumarPrakash HiremathNessuna valutazione finora

- Qualification Exam: Quantum Mechanics: Name:, QEID#76977605: October, 2017Documento110 pagineQualification Exam: Quantum Mechanics: Name:, QEID#76977605: October, 2017yeshi janexoNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics 1922 – 1941: Including Presentation Speeches and Laureates' BiographiesDa EverandPhysics 1922 – 1941: Including Presentation Speeches and Laureates' BiographiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Townsend, Quantum Physics, CHAP - 4, 1DPotentialsDocumento39 pagineTownsend, Quantum Physics, CHAP - 4, 1DPotentialsElcan DiogenesNessuna valutazione finora

- Berry Phase Patrick BrunoDocumento33 pagineBerry Phase Patrick Brunodyegu1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Anomalous Hall EffectDocumento44 pagineAnomalous Hall EffectImtiazAhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Berry Phase and ApplicationDocumento3 pagineBerry Phase and ApplicationAnonymous 9rJe2lOskxNessuna valutazione finora

- Berry PhaseDocumento21 pagineBerry PhaseEmre ErgeçenNessuna valutazione finora

- Jackson 14.1Documento9 pagineJackson 14.1CMPaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Jaynes-Cummings ModelDocumento6 pagineJaynes-Cummings ModelFavio90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Solution Set 3Documento11 pagineSolution Set 3HaseebAhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantum Field Theory Solution To Exercise Sheet No. 9: Exercise 9.1: One Loop Renormalization of QED A)Documento20 pagineQuantum Field Theory Solution To Exercise Sheet No. 9: Exercise 9.1: One Loop Renormalization of QED A)julian fischerNessuna valutazione finora

- Mass EnergyDocumento5 pagineMass EnergySzarastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Rigid Bodies: 2.1 Many-Body SystemsDocumento17 pagineRigid Bodies: 2.1 Many-Body SystemsRyan TraversNessuna valutazione finora

- HeisenbergDocumento8 pagineHeisenbergJiveshkNessuna valutazione finora

- Appendix C Lorentz Group and The Dirac AlgebraDocumento13 pagineAppendix C Lorentz Group and The Dirac AlgebraapuntesfisymatNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter2 PDFDocumento159 pagineChapter2 PDFShishir DasikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Spin 56-432 Spin LecDocumento293 pagineSpin 56-432 Spin LecJacecosmozNessuna valutazione finora

- Gravitational WavesDocumento1 paginaGravitational WavesjoniakomNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantum Mechanics Homework 8Documento2 pagineQuantum Mechanics Homework 8Oscar100% (1)

- Photonic Topological Insulators A Beginners Introduction Electromagnetic PerspectivesDocumento13 paginePhotonic Topological Insulators A Beginners Introduction Electromagnetic PerspectivesabduNessuna valutazione finora

- Schrodinger EquationDocumento36 pagineSchrodinger EquationTran SonNessuna valutazione finora

- Solved - A Quantum Mechanical System Starts Out in The Statewher...Documento7 pagineSolved - A Quantum Mechanical System Starts Out in The Statewher...Dennis KorirNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Quantum Field Theory For ChildrenDocumento8 pagine9 Quantum Field Theory For ChildrenAnonymous SGezgEN8DWNessuna valutazione finora

- Relativistic Electromagnetism: 6.1 Four-VectorsDocumento15 pagineRelativistic Electromagnetism: 6.1 Four-VectorsRyan TraversNessuna valutazione finora

- Classical Yang MillsDocumento7 pagineClassical Yang MillsRichard Martin MartirosianNessuna valutazione finora

- Hamiltonian Mechanics: 4.1 Hamilton's EquationsDocumento9 pagineHamiltonian Mechanics: 4.1 Hamilton's EquationsRyan TraversNessuna valutazione finora

- Relativity Demystified ErrataDocumento9 pagineRelativity Demystified ErrataRamzan8850Nessuna valutazione finora

- PhononDocumento10 paginePhononomiitgNessuna valutazione finora

- Clifford Algebra and The Projective Model of Hyperbolic Spaces PDFDocumento11 pagineClifford Algebra and The Projective Model of Hyperbolic Spaces PDFMartinAlfons100% (1)

- Atomic Physics 12 PagesDocumento12 pagineAtomic Physics 12 Pagessadam hussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Aqm Lecture 3Documento10 pagineAqm Lecture 3sayandatta1Nessuna valutazione finora

- QMSDM Part2 Solutions 8 13Documento75 pagineQMSDM Part2 Solutions 8 13Kelly WeermanNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantum Mechanics NotesDocumento21 pagineQuantum Mechanics NotesPujan MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 Quantum Theory of CollisionsDocumento267 pagineUnit 1 Quantum Theory of Collisionsrick.stringman100% (1)

- Particle PhysicsDocumento16 pagineParticle PhysicsBoneGrissleNessuna valutazione finora

- Universe Galaxy ClustersDocumento42 pagineUniverse Galaxy ClustersRanadheer AddagatlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Penrose DiagramsDocumento9 paginePenrose Diagramsbastian_wolfNessuna valutazione finora

- PEP 2020 Phase 2 Selection Test 2 SolutionDocumento7 paginePEP 2020 Phase 2 Selection Test 2 SolutionMarcus PoonNessuna valutazione finora

- Michail Zak and Colin P. Williams - Quantum Neural NetsDocumento48 pagineMichail Zak and Colin P. Williams - Quantum Neural Netsdcsi3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vector Calculus Applications in Electricity and MagnetismDocumento6 pagineVector Calculus Applications in Electricity and MagnetismSadeep MadhushanNessuna valutazione finora

- Time-Harmonic Electromagnetic FieldDocumento39 pagineTime-Harmonic Electromagnetic Fieldatom tuxNessuna valutazione finora

- Master Thesis Optical Properties of Pentacene and Picene: University of The Basque Country WWW - Mscnano.euDocumento51 pagineMaster Thesis Optical Properties of Pentacene and Picene: University of The Basque Country WWW - Mscnano.euAnonymous oSuBJMNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Integral EquationsDocumento5 pagineTypes of Integral EquationsIL Kook SongNessuna valutazione finora

- ElectromagnetismDocumento89 pagineElectromagnetismTeh Boon SiangNessuna valutazione finora

- Collision of Elastic BodiesDocumento10 pagineCollision of Elastic BodiesVinay HaridasNessuna valutazione finora

- Franck Hertz ExperimentDocumento15 pagineFranck Hertz Experimentlalal345Nessuna valutazione finora

- Inducing A Magnetic Monopole With Topological Surface StatesDocumento9 pagineInducing A Magnetic Monopole With Topological Surface StatesMike WestfallNessuna valutazione finora

- A Universal Instability of Many-Dimensional Oscillator SystemsDocumento117 pagineA Universal Instability of Many-Dimensional Oscillator SystemsBrishen Hawkins100% (1)

- 183 - PR 23 - Foucault Pendulum AnalysisDocumento2 pagine183 - PR 23 - Foucault Pendulum AnalysisBradley NartowtNessuna valutazione finora

- Perturbation TheoryDocumento4 paginePerturbation Theoryapi-3759956100% (1)

- Chapter 8: Orbital Angular Momentum And: Molecular RotationsDocumento23 pagineChapter 8: Orbital Angular Momentum And: Molecular RotationstomasstolkerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Light-Cone ApproachDocumento38 pagineThe Light-Cone ApproachSarthakNessuna valutazione finora

- Lagrangian Mechanics: 3.1 Action PrincipleDocumento15 pagineLagrangian Mechanics: 3.1 Action PrincipleRyan TraversNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnoli IdsDocumento10 pagineMagnoli IdsElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- 170644Documento3 pagine170644Elyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Flowering PlantDocumento28 pagineFlowering PlantElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- VochysiaceaeDocumento5 pagineVochysiaceaeElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Si Vous Utilisez Un Lecteur 1Documento3 pagineSi Vous Utilisez Un Lecteur 1Elyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- CloveDocumento12 pagineCloveElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- MyrtalesDocumento6 pagineMyrtalesElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Suricata 1 2014Documento512 pagineSuricata 1 2014Elyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Net - Islamweb - WWWDocumento8 pagineNet - Islamweb - WWWElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- InfoDocumento6 pagineInfoElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wildflower Booklet PDFDocumento14 pagineWildflower Booklet PDFElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Apocynaceae of NamibiaDocumento168 pagineThe Apocynaceae of NamibiaElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fertilizing Trees and Shrubs 2013Documento4 pagineFertilizing Trees and Shrubs 2013Elyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- 09 Resprocsec 02Documento52 pagine09 Resprocsec 02Elyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

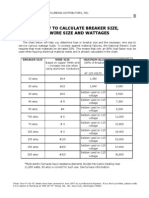

- 08 - How To Calculate Breaker Wire Size & WattageDocumento1 pagina08 - How To Calculate Breaker Wire Size & Wattageoadipphone7031Nessuna valutazione finora

- For MuslimsDocumento1 paginaFor MuslimsElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hydrogen AtomDocumento8 pagineHydrogen AtomElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Index PDFDocumento21 pagineIndex PDFElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ammonia and Urea ProductionDocumento10 pagineAmmonia and Urea Productionwaheed_bhattiNessuna valutazione finora

- T H e G o L D S T A N D A R DDocumento10 pagineT H e G o L D S T A N D A R DElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Common Questions People Ask About IslamDocumento79 pagineCommon Questions People Ask About IslamElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Who Is Allah and His ProphetDocumento66 pagineWho Is Allah and His ProphetElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Grave (Punishment and Blessings)Documento96 pagineThe Grave (Punishment and Blessings)salafi_91Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Program of Studies For New MuslimsDocumento84 pagineA Program of Studies For New MuslimsElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wives of Prophet Muhammad - Ali CarreragaDocumento180 pagineWives of Prophet Muhammad - Ali Carreragaapi-27408598Nessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Way of LifeDocumento88 pagineIslamic Way of LifeElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Americain Females Converting To IslamDocumento4 pagineAmericain Females Converting To IslamElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic View TerrorismDocumento11 pagineIslamic View TerrorismElyasse B.Nessuna valutazione finora

- The True Religion of GodDocumento27 pagineThe True Religion of GodislamanalysisNessuna valutazione finora

- 65-Finite-Element-Analysis-Of-Pipes-Conveying-Fluid Mounted-On-Viscoelastic-FoundationsDocumento14 pagine65-Finite-Element-Analysis-Of-Pipes-Conveying-Fluid Mounted-On-Viscoelastic-FoundationsDaniel Andres VargasNessuna valutazione finora

- McGraw-Edison SPI Lighting Power Drawer CCL Series Brochure 1982Documento40 pagineMcGraw-Edison SPI Lighting Power Drawer CCL Series Brochure 1982Alan MastersNessuna valutazione finora

- Bgcse Physics Paper 1 2017Documento17 pagineBgcse Physics Paper 1 2017Katlego LebekweNessuna valutazione finora

- ds65 700 PDFDocumento4 pagineds65 700 PDFkumar_chemicalNessuna valutazione finora

- UCM Question Bank 2 MarksDocumento22 pagineUCM Question Bank 2 MarksManivannan JeevaNessuna valutazione finora

- ANSA v17.0.0 Release NotesDocumento63 pagineANSA v17.0.0 Release NotesVishnu RaghavanNessuna valutazione finora

- Weeemake TrainingDocumento46 pagineWeeemake Trainingdalumpineszoe100% (1)

- Geotechnical Variation of London Clay Across Central LondonDocumento12 pagineGeotechnical Variation of London Clay Across Central LondonChiaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Antena Tipo LazoDocumento2 pagineAntena Tipo LazoMarllory CobosNessuna valutazione finora

- Fmath p2 j99Documento6 pagineFmath p2 j99SeanNessuna valutazione finora

- NEMA TS2 - OverviewDocumento22 pagineNEMA TS2 - OverviewAdalberto MesquitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Identification of Transport Mechanism in Adsorbent Micropores From Column DynamicsDocumento9 pagineIdentification of Transport Mechanism in Adsorbent Micropores From Column DynamicsFernando AmoresNessuna valutazione finora

- Shop Drawing Submittal: Project: Project No. Client: Consultant: Contractor: 20-373-DS-ARC-PE-21Documento129 pagineShop Drawing Submittal: Project: Project No. Client: Consultant: Contractor: 20-373-DS-ARC-PE-21Ernest NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- Dimensions Dog BoneDocumento5 pagineDimensions Dog BonedeathesNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawal Habeeb Babatunde: A Seminar Report OnDocumento21 pagineLawal Habeeb Babatunde: A Seminar Report OnAyinde AbiodunNessuna valutazione finora

- ML12142A123Documento58 pagineML12142A123Mohammed RiyaazNessuna valutazione finora

- Forces Balanced and UnbalancedDocumento24 pagineForces Balanced and UnbalancedInah Cunanan-BaleteNessuna valutazione finora

- Project - Silicon Solar Cell-CoDocumento55 pagineProject - Silicon Solar Cell-CoSudheer SebastianNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus - Vishwakarma Institute of TechnologyDocumento211 pagineSyllabus - Vishwakarma Institute of TechnologyAditya PophaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Compass SurveyingDocumento22 pagineCompass SurveyingCharles Carpo46% (13)

- Final Test: Grade: 3 Time: 30 Minutes Your Name: .. ScoreDocumento8 pagineFinal Test: Grade: 3 Time: 30 Minutes Your Name: .. ScoreThu NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalogo PTP 2011 Cadena Transportadoras 10818 - ENDocumento136 pagineCatalogo PTP 2011 Cadena Transportadoras 10818 - ENAriel Linder Ureña MontenegroNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematics Paper I: Question-Answer BookDocumento11 pagineMathematics Paper I: Question-Answer BookTO ChauNessuna valutazione finora

- Gestión de Formación Profesional Integral Procedimiento Desarrollo Curricular Guía de Aprendizaje 1. Identificación de La Guia de AprenizajeDocumento9 pagineGestión de Formación Profesional Integral Procedimiento Desarrollo Curricular Guía de Aprendizaje 1. Identificación de La Guia de AprenizajeMilena Sánchez LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- NEMA Grade G10 Glass Epoxy LaminateDocumento1 paginaNEMA Grade G10 Glass Epoxy Laminateim4uim4uim4uim4uNessuna valutazione finora

- Chiller Plant DesignDocumento48 pagineChiller Plant Designryxor-mrbl100% (1)

- Chapter 3: Kinematics (Average Speed and Velocity) : ObjectivesDocumento4 pagineChapter 3: Kinematics (Average Speed and Velocity) : ObjectivesRuby CocalNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011 Exam GeotechnicalDocumento9 pagine2011 Exam GeotechnicalAhmed AwadallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial 5 - Entropy and Gibbs Free Energy - Answers PDFDocumento5 pagineTutorial 5 - Entropy and Gibbs Free Energy - Answers PDFAlfaiz Radea ArbiandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 1 Overview of The FEMDocumento60 pagineLecture 1 Overview of The FEMMarcoFranchinottiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlDa EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (58)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDa EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (6)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDa EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (42)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDa EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDa EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (3)

- From Darkness to Sight: A Journey from Hardship to HealingDa EverandFrom Darkness to Sight: A Journey from Hardship to HealingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (3)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerDa EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (392)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceDa EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (51)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsDa EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceDa EverandThe Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity--and Will Determine the Fate of the Human RaceValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (517)

- Tales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceDa EverandTales from Both Sides of the Brain: A Life in NeuroscienceValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (18)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseDa EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (69)

- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsDa EverandAlgorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (722)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDa EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (8)

- A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black HolesDa EverandA Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black HolesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2193)

- Sully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonDa EverandSully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (103)

- Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”Da EverandLessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse”Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the BrainDa EverandHow Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the BrainValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (440)

- Masterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeDa EverandMasterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeNessuna valutazione finora

- Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincDa EverandPeriodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (137)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessDa EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessNessuna valutazione finora

- Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarDa EverandHero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (19)