Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Business Engineering Product Product Design Marketing Analysis Product Life Cycle Management

Caricato da

Sohail KaziDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Business Engineering Product Product Design Marketing Analysis Product Life Cycle Management

Caricato da

Sohail KaziCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In business and engineering, new product development (NPD) is the complete process of bringing a new product to market.

A product is a set of benefits offered for exchange and can be tangible (that is, something physical you can touch) or intangible (like a service, experience, or belief). There are two parallel paths involved in the NPD process: one involves the idea generation, product design and detail engineering; the other involves market research and marketing analysis. Companies typically see new product development as the first stage in generating and commercializing new product within the overall strategic process of product life cycle management used to maintain or grow their market share.

No business activity is more heralded for its promise and approached with more justified optimism than the development and manufacture of new products. Whether in mature businesses like automobiles and electrical appliances, or more dynamic ones like computers, managers correctly view new products as a chance to get a jump on the competition. Ideally, a successful new product can set industry standards standards that become another companys barrier to entryor open up crucial new markets. Think of the Sony Walkman. New products are good for the organization. They tend to exploit as yet untapped R&D discoveries and revitalize the engineering corps. New product campaigns offer top managers opportunities to reorganize and to get more out of a sales force, factory, or field service network, for example. New products capitalize on old investments. Perhaps the most exciting benefit, though, is the most intangible: corporate renewal and redirection. The excitement, imagination, and growth associated with the introduction of a new product invigorate the companys best people and enhance the companys ability to recruit new forces. New products build confidence and momentum. Unfortunately, these great promises of new product development are seldom fully realized. Products half make it; people burn out. To understand why, lets look at some of the more obvious pitfalls. 1. The moving target. Too often the basic product concept misses a shifting market. Or companies may make assumptions about channels of distribution that just dont hold up. Sometimes the project gets into trouble because of inconsistencies in focus; you start building a stripped-down version and wind up with a load of options. The project time lengthens, and longer projects invariably drift more and more from their initial target. Classic market misses include the Ford Edsel in the mid-1950s and Texas Instruments home computer in the late 1970s. Even very successful products like Apples Macintosh line of personal computers can have a rocky beginning. 2. Lack of product distinctiveness. This risk is high when designers fail to consider a full range of alternatives to meet customer needs. If the organization gets locked into a concept too quickly, it may not bring differing perspectives to the analysis. The market may dry up, or the critical technologies may be sufficiently widespread that imitators appear out of nowhere. Plus Development introduced Hardcard, a hard disk that fits into a PC expansion slot, after a year and a half of development work. The company thought it had a unique product with at least a nine-month lead on competitors. But by the fifth day of the industry show where Hardcard was introduced, a competitor was showing a prototype of a competing version. And within three months, the competitor was shipping its new product.

3. Unexpected technical problems. Delays and cost overruns can often be traced to overestimates of the companys technical capabilities or simply to its lack of depth and resources. Projects can suffer delays and stall midcourse if essential inventions are not completed and drawn into the designers repertoire before the product development project starts. An industrial controls company we know encountered both problems: it changed a part from metal to plastic only to discover that its manufacturing processes could not hold the required tolerances and also that its supplier could not provide raw material of consistent quality. 4. Mismatches between functions. Often one part of the organization will have unrealistic or even impossible expectations of another. Engineering may design a product that the companys factories cannot produce, for example, or at least not consistently at low cost and with high quality. Similarly, engineering may design features into products that marketings established distribution channels or selling approach cannot exploit. In planning its requirements, manufacturing may assume an unchanging mix of new products, while marketing mistakenly assumes that manufacturing can alter its mix dramatically on short notice. One of the most startling mismatches weve encountere d was created by an aerospace company whose manufacturing group built an assembly plant too small to accommodate the wingspan of the plane it ultimately had to produce.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Number CardsDocumento21 pagineNumber CardsCachipún Lab CreativoNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Calculation ReportDocumento157 pagineCalculation Reportisaacjoe77100% (3)

- Probability Theory - VaradhanDocumento6 pagineProbability Theory - VaradhanTom HenNessuna valutazione finora

- PH-01 (KD 3.1) Filling Out Forms (PG20) - GFormDocumento4 paginePH-01 (KD 3.1) Filling Out Forms (PG20) - GFormLahita AzizahNessuna valutazione finora

- OB Case Study Care by Volvo UK 2020Documento1 paginaOB Case Study Care by Volvo UK 2020Anima AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- EXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Documento5 pagineEXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Bendo Marjorie P.100% (1)

- Angle ModulationDocumento26 pagineAngle ModulationAtish RanjanNessuna valutazione finora

- TransistorDocumento3 pagineTransistorAndres Vejar Cerda0% (1)

- Contribution of Medieval MuslimDocumento16 pagineContribution of Medieval Muslimannur osmanNessuna valutazione finora

- READMEDocumento2 pagineREADMEtushar patelNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Plans in The Context of The 21 ST CenturyDocumento29 pagineLearning Plans in The Context of The 21 ST CenturyHaidee F. PatalinghugNessuna valutazione finora

- Davis A. Acclimating Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus Vannamei, To Inland, Low-Salinity WatersDocumento8 pagineDavis A. Acclimating Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus Vannamei, To Inland, Low-Salinity WatersAngeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Dpb6013 HRM - Chapter 3 HRM Planning w1Documento24 pagineDpb6013 HRM - Chapter 3 HRM Planning w1Renese LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Scope and Sequence 2020 2021...Documento91 pagineScope and Sequence 2020 2021...Ngọc Viễn NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Problems: C D y XDocumento7 pagineProblems: C D y XBanana QNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Test - Math As A Language - MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN WORLDDocumento8 paginePractice Test - Math As A Language - MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN WORLDMarc Stanley YaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Measures of Indicator 1Documento2 pagineMeasures of Indicator 1ROMMEL BALAN CELSONessuna valutazione finora

- CUIT 201 Assignment3 March2023Documento2 pagineCUIT 201 Assignment3 March2023crybert zinyamaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3Documento5 pagineUnit 3Narasimman DonNessuna valutazione finora

- CS3501 Compiler Design Lab ManualDocumento43 pagineCS3501 Compiler Design Lab ManualMANIMEKALAINessuna valutazione finora

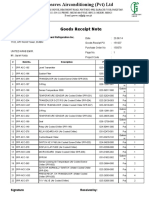

- Goods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateDocumento4 pagineGoods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateSaad PathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociology of Crimes and Ethics Suggested Answer "A"Documento34 pagineSociology of Crimes and Ethics Suggested Answer "A"Bernabe Fuentes Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Combinational Logic-Part-2 PDFDocumento25 pagineCombinational Logic-Part-2 PDFSAKSHI PALIWALNessuna valutazione finora

- I.A.-1 Question Bank EM-3 (Answers)Documento11 pagineI.A.-1 Question Bank EM-3 (Answers)UmmNessuna valutazione finora

- Summative Test in Foundation of Social StudiesDocumento2 pagineSummative Test in Foundation of Social StudiesJane FajelNessuna valutazione finora

- 448 Authors of Different Chemistry BooksDocumento17 pagine448 Authors of Different Chemistry BooksAhmad MNessuna valutazione finora

- 20235UGSEM2206Documento2 pagine20235UGSEM2206Lovepreet KaurNessuna valutazione finora

- Manish Kumar: Desire To Work and Grow in The Field of MechanicalDocumento4 pagineManish Kumar: Desire To Work and Grow in The Field of MechanicalMANISHNessuna valutazione finora

- 61annual Report 2010-11 EngDocumento237 pagine61annual Report 2010-11 Engsoap_bendNessuna valutazione finora

- GATE Chemical Engineering 2015Documento18 pagineGATE Chemical Engineering 2015Sabareesh Chandra ShekarNessuna valutazione finora