Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lit Review Community Involvement

Caricato da

marybethlynn1Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lit Review Community Involvement

Caricato da

marybethlynn1Copyright:

Formati disponibili

The Effects of Community Involvement in the Public Schools of America Research Proposal Angie Atwell Michelle Christerson Kevin

Graham Robert Herrold Mary Beth Lynn Meghan Morris Trey Thompson ESR 505 Summer, 2012

Introduction Over the course of this paper, the reader will be able to take an extensive look into the effects of community involvement in the public schools of America. Based on the articles that are present in this piece one will find that there are a number of members that are identified when referencing the partners that can contribute to the community involvement. One will also notice that various methods will be employed to help educators gather and integrate data that is generated from surveys and interviews. Ultimately, we want to allow the reader to be able to utilize the information that has been collected in this writing, and to use the information as an impetus or spring board for them to understand how important community involvement is in schools. Thus enabling them to be able to advocate for reforms in the realms of schools and politics. We hope that after reading and gleaning new information from the various texts represented in the writing that educators will understand the effects of how community involvement and/or lack of community involvement greatly impacts a multitude of facets in and throughout the culture and educational environment of our nation's school systems. Literature Review Arts and Afterschool: A Powerful Combination Arts and Afterschool: A Powerful Combination sheds light onto the idea that community involvement can aid in student achievement. This article discusses the importance of using the arts in afterschool programs because of the many benefits that it offers to the school and the community. According to the article, "the integration of the arts into the afterschool programs helps build and reinforce important student learning" (Afterschool Alliance, 2005, para. 1). Some of the areas the arts can help strengthen are "teamwork, responsibility, persistence, self-discipline, and presentation skills," as well as "promote learning in core subjects as reading, writing, and math (para. 1). The article sites research that has been done on the effects of art on student achievement that states, "mental stimulation and life lessons provided by arts education" can "help youth succeed in school and later in life" (para. 3). The article offers many examples of how individual forms of art can improve achievement, such as how the reading and acting of drama can help with reading comprehension, and music can help with counting (para. 3). One of the many examples of increased student achievement that the article uses is from an afterschool program from Dallas, Texas named ArtsPartners. This program has seen definite gains in student achievement and states that, fourth-graders average gain on the Reading Texas Learning Index is more than 6 percentage points higher than those students who did not receive ArtsPartners enrichment (para. 6). However, gains in student achievement is not the only benefit. Afterschool programs are a way to bring the community and schools together. The article states, "Afterschool programs are often excellent venues to build partnerships with the local arts community, such as dance companies, theater troupes, music groups,

3 cultural associations, and museums" (Afterschool Alliance, 2005, para. 4). Another benefit of uniting the community through afterschool programs is that "these partnerships bring students important, often missing, connections to caring adults and community groups and institutions that can build the students' repertoire of skills and linkage to people for the future" (para. 4). By uniting a community through afterschool arts programs, students can benefit even more through increased academic achievement and closer community ties. After reviewing this article, it seems that afterschool programs are a proven way to increase student achievement and community involvement in schools. However, when looking at schools in urban areas, it is important to remember funding and resources available in the community. Many urban schools are located in impoverished areas or in areas where the families are listed as low-income. It is not always possible to bring in enrichment programs without adding extra expenses to the students families. I have previously worked in an afterschool program that offers art enrichments, but many students could not afford to participate and there were few scholarships available. There is also the fact that resources are not available in all areas. Not every school community has dance companies, theater troupes, music groups, etc. that are available to serve the afterschool programs. It would not be possible to build community ties with these programs if they are non-existent. Another factor that is very important to the success of afterschool programs ability to improve student achievement is the curriculum and structure. This article only focuses on successful afterschool art programs, but I worked at an afterschool program that I believe lacked the proper curriculum and structure to improve student achievement. I believe that in order to be effective, afterschool art programs need to have a curriculum and structure that are tested and proven to help student achievement; merely having students take art classes is not enough to improve student achievement. I personally believe that community-based afterschool art programs can be a great way to aid in student achievement and help build or improve community ties. However, these programs are not always available in every area, and funding is not always available. It is also important to remember that afterschool art programs need to have a proven curriculum and structure in order to reach the highest potential in student achievement. Community Service and Service Learning Reducing Academic Achievement Gaps: The Role of Community Service and Service-Learning was a study of 6-12th grade students that focused on the relationship between community service and service-learning experiences, academic success, and socioeconomic status (SES) (38). The contributing factors displayed a positive response in high-poverty, urban schools in regards to attendance, engagement, and academic progress. The authors referred to community service and learning experiences as experiential education, and they suggested that it contributed to achieving academic outcomes and developmental responsiveness (39). Statistics stated that students with lower SES, 40% of which are African American, were linked to a wide range of indicators of child and adolescent well-being, including student academic achievement, because they had less stable families and greater exposure to environmental toxics and violence. The study also discussed the developmental attentiveness strategy, or human

4 development, and its effectiveness on student achievement. It associated school reform with the developmental needs of students and the broader community environment (41). The idea concluded that restructuring the school experience to provide a better fit with the developmental needs of children was crucial in the greater achievement for all. One of the elements of the strategy incorporated authentic instruction that engaged students and connected subject matter to real-world problems through community engagement (41). Overall, there was an extremely positive change in students that participated in service learning and/or community involvement, such as the belief that they were contributing to the community; they were less bored than in traditional classrooms; they were more engaged in academic tasks and general learning; and lastly, they were more accepting of diversity. This study was quantitative and surveyed 1,799 schools, including more than 217,000 students. The sample was also weighted by race/ethnicity and urbanicity proportions of the 2000 census (45). The surveys were Likert-scaled and included factors such as student service and duration to others, school poverty levels, student SES, grades, attendance, and commitment to learning assets. The numbers largely displayed that service-learning and community service was an extremely valued strategy for increasing student achievement and developmental factors. I personally believe this study was done very well and examined a large sample of students, therefore increasing its validity and relevance. I was hoping to see the benefits of service-learning and community service in regards to decreasing the achievement gap, and based on the research, I fully believe the strategy should be utilized in every classroom in the United States, especially in urban school districts. Varieties of Parental Involvement in Schooling This article references how our nation is placing a great amount of emphasis on accountability within the schools, and that the relationships with parents are also key components in this shift. The article discusses the amazing qualities that these types of partnerships can and do create for the children, parents, and teachers alike. In the same breath, it also various historical happenings that have shaped and created the ever widening gap between parents and the school system, especially as the children move into middle and secondary school placements. After reading about the various results that were produced after researching and investigating this topic throughout the 19th century to the present, I have concluded that I agree with the authors. Whether in undergraduate courses or graduate level coursework, the issue of parent involvement is always a hot topic of conversation. I believe that parents are key players in making certain that the needs of their children are being met, whether that is academically, socially, or emotionally. If their voices are silenced or minimal, then we are truly tailoring our calendars, curriculum, events, and so on based on our needs and interests. I think that it is a travesty that the value of the parental voice in planning and instruction has been limited in such a way. For example, if the calendar is created without understanding the core values of the people that live within the community, there may be dates and times that are scheduled, and they are in direct conflict with those the parents. If that is the case, then this could be one of the many things that attribute to the low parental involvement. In the advancement of teaching as a profession, we, as educators,

5 have viewed ourselves as the professionals, and possibly created unspoken biases that have alienated parents. Research shows that the inclusion of the parents involvement in the school has increased student confidence, attendance, graduation, behavior management, and so on. The reverse if also true that parents and teachers both developed a greater sense of belonging and value, due to the nature of these partnerships. In conclusion, I believe that we should strive to create and maintain these relationships so that our school and classroom communities will become a place of growing and learning for all of its respective members. Action Steps for Implementing Family and Community Involvement in School Health Students are less likely to succeed when communities are economically deprived, disorganized, and lack opportunities for employment or youth involvement; when families do not set clear expectations, monitor childrens behavior, or model appropriate behaviors; and when schools present a negative climate and do not involve students and their families. Family and community involvement are crucial in our public schools today; we have so much to risk if we think community and schools should be separated. The article I read, Action Steps for Implementing Family and Community Involvement in School Health, gives many examples of how to improve the relationship of school personnel, and community members and why its important. Too often, parents are blamed for not being a good enough support system for their children, when really it is also the school's responsibility to make the community members feel welcome in their schools. All parents and community members should be able to go to the schools as a safe haven. The article stated that by developing partnerships with local businesses and services groups, relationships would advance and student learning as well as assist schools and families. When I worked in District 124, the parents who worked in the community often came to volunteer and share their job experiences. We had several students who parents were either police officers or firefighters in Evergreen Park, and the respect really grewfor both parties. Parents can help being a part of their childs learning experience, too. For example, if they cannot attend a meeting on a specific day, they could make arrangements to meet on another day; or they could pick a place to meet in the community if needed. Community members could also set up programs for parents and students that include academic classes, literacy training, career preparation, early childhood education, childrens health, and assistance in finding helpful services in the community. I believe that if parents were given the opportunity to come in and out of the school freely (after checking into the office, of course) the bond between the parents, teachers, and even the students would grow stronger. The school, the family, and the community each have its own unique way to reach students to improve their learning experiences and can influence students behaviors in different ways. If they work together, they can provide an environment in which students can learn and mature effectively. The Effect of Professional Learning Communities: Teachers as Community In the article Professional Learning Communities in Partnership: A 3-Year Journey of Action and Advocacy to Bridge the Achievement Gap, Patricia Hoffman and

6 her co-authors researched the effects on participants learning, understanding and overall satisfaction over the course of a three-year-long commitment to participate in professional learning communities (PLCs.) The foundation of the research is the authors statement that a new model is needed for professional development among teachers. Hoffman asserts that the traditional method of bringing in a professional for a one-time seminar or presentation does not produce deep understanding. The author argues that the PLC model which advocates continuous development and a constant feedback loop would produce a more profound effect on teachers development. The study follows Professional Development Schools (PDSs) which focus on professional development and collaboration across multiple districts. This is usually done with the cooperation of a University. The guidance council of the PDS in this particular study decided to focus on three common areas of concern in improving student performance: early-childhood readiness, English-language learners (ELLs,) and familyschool-community partnerships. Participants in the study were each assigned to one of these areas of concern, and these assignments constituted the groups that were the PLCs. These PLCs convened once every three weeks over the course of three years. PLC meetings served as a place for members to review research, discuss ideas and develop plans of action for each of their respective areas of concern. At the end of the three year period, Hoffman and her co-authors present quantitative and qualitative research on these PLCs in the form of surveys and focus groups. The authors contest that this data shows conclusively that PLCs had a positive effect on those that participated in them. Some tangible evidence of the positive results of the PLCs included the successful writing of two grants by the family-school-community partnership PLC, as well as position papers written and submitted to the legislature by the other two PLCs. The authors conclude that more intentional focus on organizing the PLC meetings, a more consistently high level of involvement of PLC members, as well as more specialized participants within PLCs could have made the PLCs more successful. I personally find the authors arguments to be encouraging, but perhaps wanting for data. I dont think there is really enough hard evidence to back up Hoffmans claims that PLCs are an effective model of professional development. Hoffmans data shows us that the members of the PLCs classified themselves as being very active if they attended four to six meetings per year, and somewhat active if they attended one to three meetings per year. Forty percent of participants classified themselves as somewhat active. That sort of low attendance can make for some pretty significant inconsistency issues, and the author points out later that more active involvement in the groups could have made a big difference in the PLCs. Additionally, Hoffman points to in-fighting in the family-school-community partnership PLC that stalled their progress for the better part of three years! Meanwhile, the early-childhood PLC was making deep, meaningful progress almost immediately. I believe this kind of variation points to a need for more explicit expectations and timelines for PLCs as they develop. It should be noted that after the family-school-community finally got down to work they were able to successfully write two grants to benefit their districts. Another problem I would point out in Hoffmans data is that the groups she is researching are so small. There were only 57 participants in all three PLCs combined. And when a survey to collect data on the PLCs was sent out to participants at the end of the three years, only 39% of those from the program responded. Aside from the survey,

7 nine persons participated in three different focus groups. And this is the bulk of the data collected from their research. Hoffman argues that though the response rate was low, the participants did represent a good cross-section of the groups. And she also encourages us to appreciate the data derived from each of these participants as they have all been in their field for at least 11 years. Still for me, the low numbers just do not seem to point very conclusively to any compelling answer as to whether or not PLCs really make a difference for teachers and students. To conclude on a positive note, there are things to like in Hoffmans article. I believe that PLCs and other models like it can really affect change in our communities. As we have encountered in the last few weeks as students of urban education and its unique challenges, we have been told time and again that forming relationships is what makes the biggest difference in the education of a child. I think this is true of students and true of the professionals that seek to help students succeed. It has been shown that through constantly evaluating ourselves, our profession, and the culture that surrounds us, we can become champion teachers. I think Hoffmans article shows though, that this collaboration must be thoughtful, oriented toward specific goals (for teachers and students,) and very well organized. Effects on Teacher Morale The article Preparing Urban Teachers to Partner with Families and Communities suggests that family/community involvement increases not only student achievement, but also teacher morale. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 96). The article suggests that graduate training programs should require a class on school, family, and community partnerships (or homeschool relations, or something similar); and this type of course should be considered as important and central as the teaching of reading, math, or other core subjects. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 97, 98). The study used both semantic differential analysis and qualitative analysis to investigate their ideas. The semantic differential analysis was used to measure teacher candidates attitudes towards family and community involvement. This was done by administering surveys to teachers in two different masters program. The survey was given the first night of the course as well as the last night. The survey asked the individual to select where his or her position lies on a scale between two bipolar adjectives. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 100). The qualitative portion of the investigation utilized three different methods of data collection: individual and small group interviews, course evaluations, and analysis of asset maps completed by students as part of the course. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 101). The researchers then used this data, as well as data obtained from interviews and an asset map project to answer the following questions: What attitudinal changes, if any, emerged in teacher candidates through their experience in the Family and Community Involvement Course: (a) the nature of the change; (b) factors influencing the change; and (c) the depth of change? (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 102) The results showed that teachers attitudes toward family and community involvement changed through the duration of their course work. Many teachers showed a change from a negative to positive view of the role and importance of families and communities. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 104). Additionally, participants discovered a plethora of valuable resources in the community that they could connect to

8 students and their families. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 104). Another aspect of the results was that teachers gained awareness of their role as change agents and how this awareness affected them and their students in a positive way. (Warren, Noftle, Ganley, Quintanar 105). Independent School As my group has chosen to investigate whether or not there is a relationship among community involvement and student achievement, I have decided to critique an article entitled Bridge the DivideTurning Social Divisions into Opportunities. As the achievement gap present in American education persists, I cant help but wonder, what will it take for communities to recognize the importance community involvement plays in helping our failing schools. This article offers some solace, as this article chronicles Detroits Cranbrook Schools unwavering attempt to build a sense of community inward and out through a public-purpose partnership called Bridge the Divide with the University of Michigan, various urban institutions, and public school students in [their] HUB program (p.82). Cranbrook Schools has taken the critical first steps in encouraging and promoting community involvement through identifying the obvious divide within the Detroit Metropolitan area. Working hard to develop and promote an inclusive culture within, the Bridge the Divide movement recognizes that the notion of merely throwing people together (p.82) does not promote a true sense of community. Through working with their partners, Cranbrook Schools has developed a program that helps students in the areas of empathy building, community discover, and community action. Through this training, it is believed that students will become part of a much needed and cosmopolitan generation of social problem solvers invested in the future of their communities (p.82). While aspiring educators are taught about the importance of promoting a sense of community in the classroom setting, Cranbrook Schools is actually doing so. The program is having students, all students, international, urban, and metropolitan students partake in intergroup dialogue where they tackle controversial topics. One might wonder, what does a conversation about stereotypes and controversial topics look like among students, but the beauty of the program is that the students open their minds and approach these topics with an honesty and candor that most adults would find daunting (p.83). Being able to see things from a different perspective makes many topics that once seemed irrelevant seem quite important after students partake in intergroup dialogue. These tough conversations provide students with an opportunity to look at things in a different light. I could not imagine a more powerful way to challenge my personal stereotypes and preconceived notions than hearing the pain they cause someone else. So, we want more community involvement and we think it could have a dramatic affect on our failing schools, but what exactly does community involvement look like? Well, Bridge the Divide does an excellent way of illustrating small ways that the community can come together. Once these students have recognized the need for community involvement and looked deep within, they go out and seek change for the greater good of their community. Through completing Bridge projects, the program has collaborated with members of the community for community art projects and urban gardening projects, too.

9 While we consistently talk about the importance of community, this article illustrates the importance of putting actions behind our words. When we ask our students to look within, really examine who they are, and recognize their potential to accomplish and influence great change, we are promoting the idea of excellence, which is what we need in urban classrooms. While we strive for excellence, we need more, more from our communities. We want to inspire our students to be activists for themselves and their communities, as they are truly capable of inspiring dramatic change. It is no longer enough to be an academically excellent school educating academically talented students when the community around you is falling apart (p.84). Methodology Sample/Participants Qualitative: We plan to conduct sit down interviews with five community members and five teachers from various schools that have been turned around by AUSL. Ideally, we would like to interview teachers who have observed the changes that have occurred as a result of the turnaround initiatives within their schools. We are also looking to interview community members with varying viewpoints, so we are going to interview a variety of parents, community leaders, and any other individuals that are actively involved in the community. Quantitative: In addition to our interviews, we will be conducting a survey that will be given to both elementary and secondary educators in AUSL turnaround schools, in addition to various members of the community. Our survey will ask an array of questions pertaining to the correlation between student achievement and community involvement. Instrument Quantitative: Our survey is comprised of five demographic questions that pertain to the respondents' relationships to the community. Following the demographic questions, there are an additional 16 questions, which are a combination of yes or no and Likert-scale questions. Questions 12-19 are specific to parents, therefore teachers and community members will only be asked to respond to questions 1-11 and 20. Some questions on the survey are geared toward parents with students from specific grade levels, and thus the survey can provide us with more precise information about parent thoughts in regards to student achievement and community involvement within specific age ranges. Procedure Qualitative: Our sit down interviews with five community members and five teachers from various turnaround schools will be set up like a conversation. Each interview will be audio taped and the interviewers will jot down notes throughout the interview. By framing the conversation and explaining that we are taking a closer look at the correlation between community involvement and student achievement, we will then facilitate a conversation about the interviewee's thoughts and observations in regards to the proposed topic. Quantitative: All teachers and community members will be given a brief synopsis of why

10 the survey is being given. All participants anonymity will be ensured, as they will not be asked to identify themselves on the survey. Participants will be asked to carefully consider each question before answering, and they will be given an unlimited amount of time to complete the questions. Data Analysis After conducting our interviews and administering the survey, we will analyze both the qualitative and quantitative results carefully. Taking a look at the qualitative results obtained from the interviews, we will try to identify common themes and/or opposing positions. We will work to write a narrative that showcases a culmination of what we learned about educators and community members views of the correlation among student achievement and community involvement. We will then take a look at the quantitative data from the surveys and analyze it using Microsoft Excel. Through the identification of commonalities and differences within the data collected, we will delve deeper and note how these commonalities and differences can be tied into the resulting attitudes that were discovered through the use of the qualitative data. Conclusion There seems to be a reoccurring theme of community involvement in successful schools, one that ceases to exist in our urban schools. After extensive research on community involvement in the schools, we decided to create a survey and an interview to find out if there is a direct correlation between community involvement and student achievement. We believe it would be most beneficial to interview AUSL teachers to understand their outlook of schools that once have not had any community contributionto schools that now have a strong connection with the community. Understanding community involvement in the schools is a complex topic but teachers need to be advocates for their students and knowledgeable on this aspect of student achievement.

11

References Afterschool Alliance (2005). Arts and afterschool: a powerful combination. Afterschool Alert, 21. Retrieved from http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/issue_briefs/issue_arts_21.pdf Anfara, V. A., & Mertens, S. B. (2008). Varieties of parental involvement in schooling. Middle School Journal, 39(3), 58-64. Retrieved from http://www.amle.org/publications/middleschooljournal/articles/January2008/Article8/tabi d/1579/Default.aspx Boncana, M., Lopez, G. R. (2010). Learning from our parents: implications for schoolcommunity relations. Journal of School Public Relations, 31(4), 277-302. Flono, F., Kettering, F. (2010). Helping students succeed: communities confront the achievement gap. Kettering Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED510122 Gordon, M. F., Louis, K. (2009). Linking parent and community involvement with student achievement: comparing principal and teacher perceptions of stakeholder influence. American Journal of Education, 116(1), 1-32. Hoffman, P., Dahlman, A., & Zierdt, G. (2009). Professional Learning Communities in Partnership: A 3-Year Journey of Action and Advocacy to Bridge the Achievement Gap. School-University Partnerships, 3(1), 28-42. Marx, E. & Wooley, S. F. (Eds.) (1998). Health Is Academic: A Guide to Coordinated School Health Programs. New York: Teachers College Press. 1998 by Education Development Center, Inc. http://www2.edc.org/makinghealthacademic/concept/actions_family.asp Scales, P. C., Roehlkepartain, E. C., Neal, M., Kielsmeier, J. C., & Benson, P. L. (2006). Reducing Academic Achievement Gaps: The Role of Community Service and ServiceLearning. Journal of Experiential Education, 29(1), 38-60. Warren, S. R., Noftle, J. T., Ganley, D. D., & Quintanar, A. P. (2011). Preparing urban teachers to partner with families and communities. School Community Journal, 21(1), 95112. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/EJ932202.pdf

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Socratic SeminarDocumento5 pagineSocratic Seminarmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Double Plan: Why Was The Murder of Emmett Till A Pivotal Moment For The Civil Rights Movement?Documento3 pagineDaily Double Plan: Why Was The Murder of Emmett Till A Pivotal Moment For The Civil Rights Movement?marybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Double Plan: What Is One Technique You Have Learned That Helps You When Comparing and Contrasting Texts?Documento2 pagineDaily Double Plan: What Is One Technique You Have Learned That Helps You When Comparing and Contrasting Texts?marybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- SpEd 506 School Profile PaperDocumento4 pagineSpEd 506 School Profile Papermarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fieldwork ReportDocumento2 pagineFieldwork Reportmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fieldwork ReportDocumento2 pagineFieldwork Reportmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- SpEd 506 LRE PaperDocumento4 pagineSpEd 506 LRE Papermarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- MLE 500 Shadow Study ObservationDocumento1 paginaMLE 500 Shadow Study Observationmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS Data ObservationDocumento1 paginaEPS Data Observationmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fieldwork ReportDocumento2 pagineFieldwork Reportmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- RLR Final ReflectionDocumento2 pagineRLR Final Reflectionmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS 541 Planning PaperDocumento5 pagineEPS 541 Planning Papermarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS Planning CommentaryDocumento6 pagineEPS Planning Commentarymarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS513 Assessment of Student Learning PaperDocumento5 pagineEPS513 Assessment of Student Learning Papermarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS 541 FormativeAssessmentProjectDocumento3 pagineEPS 541 FormativeAssessmentProjectmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Community Walk Reflection Spring 2013Documento2 pagineCommunity Walk Reflection Spring 2013marybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- EPS 541 Formative Assessment PaperDocumento8 pagineEPS 541 Formative Assessment Papermarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concept MapDocumento1 paginaConcept Mapmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Community Walk ReflectionDocumento2 pagineCommunity Walk Reflectionmarybethlynn1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- IST Graduate Prospectus 2014Documento149 pagineIST Graduate Prospectus 2014rizwan_alviNessuna valutazione finora

- In Gov cbse-SSCER-141193552021Documento1 paginaIn Gov cbse-SSCER-141193552021vinodvohra297Nessuna valutazione finora

- Acting Crazy A Training Program That Strengthens Empathic Listening, Awareness, and Creativity For Psychology Students.Documento218 pagineActing Crazy A Training Program That Strengthens Empathic Listening, Awareness, and Creativity For Psychology Students.william_oakley4654100% (1)

- Section A (Demographic Profile) : Difficulties 5 4 3 2 1Documento3 pagineSection A (Demographic Profile) : Difficulties 5 4 3 2 1remus gatunganNessuna valutazione finora

- Morocco TIMSS 2011 Profile PDFDocumento14 pagineMorocco TIMSS 2011 Profile PDFالغزيزال الحسن EL GHZIZAL HassaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Believable CharactersDocumento16 pagineBelievable Charactersapi-297752616Nessuna valutazione finora

- BernardoDocumento4 pagineBernardoKay PlataNessuna valutazione finora

- Anskey Profed Preboard ADocumento14 pagineAnskey Profed Preboard ABernard Baradero Official100% (7)

- InstructorDocumento4 pagineInstructorapi-77838415Nessuna valutazione finora

- Should Private Education Be Banned?: Perry Mccabe, Buhler, KansasDocumento8 pagineShould Private Education Be Banned?: Perry Mccabe, Buhler, KansasrefaratNessuna valutazione finora

- ข้อสอบเตรียมทหาร กองทัพเรือ ภาษาอังกฤษ 2547Documento9 pagineข้อสอบเตรียมทหาร กองทัพเรือ ภาษาอังกฤษ 2547BLUEDOJINSNessuna valutazione finora

- World Alzheimer Report 2022Documento416 pagineWorld Alzheimer Report 2022bowman1977Nessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. AI Summer Camps: Opportunities and Gaps For Youth CSET Data BriefDocumento17 pagineU.S. AI Summer Camps: Opportunities and Gaps For Youth CSET Data BriefKanishk DeepNessuna valutazione finora

- Open UniversityDocumento22 pagineOpen UniversityJerelmaric T. BungayNessuna valutazione finora

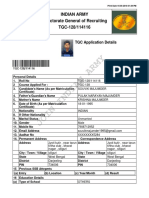

- TGC-128 114116 16 5 2018Documento4 pagineTGC-128 114116 16 5 2018SOUVIK MAJUMDERNessuna valutazione finora

- GE Healthcare Scholarship Program DetailsDocumento2 pagineGE Healthcare Scholarship Program DetailsGadeer AyeshNessuna valutazione finora

- IQDocumento16 pagineIQmoinahmed99Nessuna valutazione finora

- Caap 6615 201402 Shepard CourseDocumento7 pagineCaap 6615 201402 Shepard Courseapi-308771766Nessuna valutazione finora

- (Specific Bylaws) Membership Status Upgrade PDFDocumento2 pagine(Specific Bylaws) Membership Status Upgrade PDFHaniifa HendyNessuna valutazione finora

- Debate FeedbackDocumento3 pagineDebate FeedbackNorqueen T. DumadaugNessuna valutazione finora

- Becoming The Best": Cooperating TeachersDocumento72 pagineBecoming The Best": Cooperating TeachersMichelle ZelinskiNessuna valutazione finora

- IndisciplineDocumento76 pagineIndisciplineYushreen JambocusNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Details of Participant: Result:PASSDocumento1 paginaActivity Details of Participant: Result:PASSLoga BalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Education: Jacqueline R. Flores, Alcris Jan A. Angeles, Mr. Francis C. PangilinanDocumento3 pagineDepartment of Education: Jacqueline R. Flores, Alcris Jan A. Angeles, Mr. Francis C. PangilinanJackie Ramos Flores - Lipana100% (1)

- Discipline Report: Merry Elementary School Richmond CountyDocumento4 pagineDiscipline Report: Merry Elementary School Richmond CountyJeremy TurnageNessuna valutazione finora

- MATH 8 - Q1 - Mod12 PDFDocumento17 pagineMATH 8 - Q1 - Mod12 PDFALLYSSA MAE PELONIANessuna valutazione finora

- Hbsc3403 - v2 - Planning and Assessing Science Teaching & LearningDocumento7 pagineHbsc3403 - v2 - Planning and Assessing Science Teaching & LearningKilik GantitNessuna valutazione finora

- Busick Traci MPDocumento36 pagineBusick Traci MPReffinej Abu de VillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dibels Assessment Paper FinalDocumento15 pagineDibels Assessment Paper Finalapi-473349564Nessuna valutazione finora