Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Skincancerpreventionyouth PDF

Caricato da

El MarcelokoDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Skincancerpreventionyouth PDF

Caricato da

El MarcelokoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [Universidad Del Norte] On: 04 January 2012, At: 12:50 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Social Marketing Quarterly

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usmq20

It's a Beautiful Day for Cancer: An Innovative Communication Strategy to Engage Youth in Skin Cancer Prevention

Sofia Potente, Jackie McIver, Caroline Anderson & Kay Coppa Available online: 19 Aug 2011

To cite this article: Sofia Potente, Jackie McIver, Caroline Anderson & Kay Coppa (2011): It's a Beautiful Day for Cancer: An Innovative Communication Strategy to Engage Youth in Skin Cancer Prevention, Social Marketing Quarterly, 17:3, 86-105 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15245004.2011.595604

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Its a Beautiful Day . . . for Cancer: An Innovative Communication Strategy to Engage Youth in Skin Cancer Prevention

BY SOFIA POTENTE, JACKIE MCIVER, CAROLINE ANDERSON, AND KAY COPPA

ABSTRACT

Despite 3 decades of traditional media campaigns to raise awareness about skin cancer, Australian youth continue to exhibit poor sun protection behaviors. This article reports on a creative promotional strategy that used entertainmenteducation and social media marketing to stimulate dialogue and address barriers to sun protection. The campaign centered on an ironic music video launched across multiple media channels, with a focus on social media sites. Process evaluation included campaign reach; and online surveys and thematic analysis of online conversations appraised sun protection attitudes and behaviors. The video received 250,000 views in 4 months, and online surveys identified positive differences between those exposed and not exposed to the video in attitudes toward skin cancer risk, perceived ability to avoid skin cancer by regularly using sun protection, and several self-reported sun protection behaviors, but no differences in peer perceptions of tanning. Of those who watched the video, 25% forwarded the video to friends, 44% reported that the video changed the way they felt about sun protection, and 19% of spontaneous online comments reported an intention to change behavior. The campaign results suggest that entertaining, peer-to-peer messages can be used to engage youth with an important health message for skin cancer prevention.

CASE STUDY

Introduction Australia has the highest rates of skin cancer in the world (International Agency for Cancer Research, 2004), with over 10,600 people diagnosed with melanoma each year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Association of Cancer Registries, 2007). Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation during childhood and adolescence is a critical factor in increasing the risk of skin cancer later in life; however, a large number of skin cancers can be prevented by practising effective sun protection to reduce UV exposure and avoid sunburn (Armstrong, 2004). This protection includes using sunscreen, wearing sunglasses and hats, seeking shade, and covering up with clothing (Cancer Council NSW, 2010). Compared to adults, Australian youth spend longer periods of time in the sun, experience higher rates of sunburn, and use lower levels of sun protection (Dobbinson et al., 2008; Livingston, White, Ugoni, & Borland, 2001). Many factors combine to present barriers to effective sun protection among young people. Sun protection is not consciously considered or discussed among peers and is associated with disengaging, authoritative messages (Potente, Coppa, Williams, & Engels, 2011). Perceptions of personal skin cancer risk tend to be low, as young people report a sense of immortality and do not focus on the long-term consequences of their actions (Potente et al., 2011). Tanned skin is commonly associated with health, attractiveness, and beach culture (Bell, 1992). Youth are primarily concerned with the perceptions of their peers, and a tan is seen to be an important factor in an individuals ability to fit in with the group (Potente et al., 2011). Finally, sun protection is believed to be often unachievable a cumbersome act that disrupts the spontaneous, unplanned nature of the adolescent lifestyle (Potente et al., 2011). Youth are therefore a priority audience for skin cancer prevention initiatives in Australia. As a result of years of traditional marketing communication campaigns, youth do have high levels of awareness and knowledge about skin cancer risks and sun protection methods (Coogan, Geller, Adams, Benjes, & Koh, 2001; Dixon, Borland, & Hill, 1999; Dobbinson et al., 2008; Schofield, Freeman, Dixon, Borland, & Hill, 2001). However, to motivate this target group to adopt effective sun protection, communication strategies need to move beyond knowledge and address the key barriers to sun protection (Potente et al., 2011). Entertainment media such as TV, movies, music videos, and magazines have been shown to have a significant impact on youth healthrelated attitudes and behaviors (Strasburger, Jordan, & Donnerstein, 2010). Entertainment-education strategies build on this to develop media messages both to entertain and educate, in order to increase audience members knowledge about an educational issue,

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

87

CASE STUDY

create favourable attitudes, and change overt behavior (Singhal & Rogers, 1999, p. 9). This concept has taken on many forms, from radio serials and television programs to rock concerts and music videos (Singhal & Rogers, 1999). Due to its popularity and influence, music is a particularly effective way to reach youth audiences (Keshen, 2008). For example, John Hopkins University demonstrated that celebrity-based rock music videos were able to stimulate peer-to-peer dialogue and had a positive impact on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior related to sexual responsibility among youth in developing countries (Singhal & Rogers, 1999). The youth demographic has actively embraced digital media, with a 2008 Australian study reporting that Australian youth spent an average of 2.9 hours per day using the Internet, and 91% believed the Internet was a highly important aspect of their lives (Australian Communications and Media Authority, 2009). For example, 90% of young people use social networking sites such as MySpace and Facebook to share ideas and content and to interact with friends (Australian Communications and Media Authority, 2009). Recognizing these online trends, social media marketing (SMM) is increasingly being used to reach adolescents and stimulate a conversation en masse. SMM is a way of using the Internet to collaborate, share information, and have a conversation about ideas or causes we care about (Wilcox & Kanter, 2007, p. 15). SMM can benefit social marketing campaigns, as increased peer-to-peer dialogue on social networking sites has the potential to change young peoples attitudes and behaviors (Montgomery & Chester, 2009). While social marketing campaigns have utilized digital media channels, there are few published research studies that describe both the practice and impact (Uhrig, Bann, Williams, & Evans, 2010). In 2007, World Vision created a satirical video and MySpace page contrasting the trials in life for a typical Western teenager with life in Africa (World Vision, 2010). The YouTube video received over 200,000 views in four days and sparked 7,000 comments, but further impact has not been published. Road Safety UK (British Road Safety, 2010) and the Roads and Traffic Authority in New South Wales, Australia (Roads and Traffic Authority NSW, 2010) have both used SMM to complement traditional media channels in youth campaigns, but to our knowledge, evaluation of the SMM component has not been reported. SMM presents new opportunities to deliver entertainment-education messages to a youth audience significantly increasing reach and facilitating conversation online (Thackeray, Neiger, Hanson, & McKenzie, 2008). This study set out to determine whether entertainment-education strategies could be combined in a

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

88

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

creative communication campaign to improve sun protection behaviors. More specifically, it aimed to:

& &

Engage youth and encourage peer-to-peer dialogue about skin cancer prevention Improve attitudes to effective sun protection, specifically in relation to low perceived risk of skin cancer, positive peer perceptions of tanning, and belief in ability to avoid skin cancer by using sun protection Improve the scope of sun protection behaviors.

&

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Methods

Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer: A youth sun protection campaign

Cancer Council NSW (CCNSW) is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to defeating cancer in New South Wales, Australia. CCNSW partnered with youth-oriented communication agencies to develop and implement an unbranded communications campaign targeting youth aged 1424 years. It employed irony, black humor, and exaggeration to highlight the dangers of excessive tanning and to encourage young people to adopt five key methods of sun protection. The video was unbranded to allow young people the opportunity to discover and share it as a music video, rather than a health campaign. The decision was informed by the formative research that identified young people often switch off from messages of authority (Potente et al., 2011). The campaign was called Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer, a confronting statement designed to spark debate. It featured a music video performed by an Australian hip-hop artist given the name of Al Bino, and well-known American music producer Lyrics Born (Cancer Council NSW, 2008). The name Al Bino was selected to communicate that it is not necessary to be tanned to be cool, contrary to prevailing norms in the target audience about the desirability of a tan. The Albino Association of Australia was consulted on this decision to ensure it didnt cause inadvertent harm to those with the albinism condition. Focus testing with ten pairs of young people was used to test, shape, and refine the creative concept of a hip-hop artist delivering a skin cancer message. Launched in December 2008, the music video demonstrated the social and health-related consequences of excessive tanning. It portrayed an unnamed male teenager who neglected to use sun protection due to vanity and a desire to appear attractive to his peers. The costs of this unprotected sun exposure were presented in an exaggerated manner as a grotesque animated melanoma grew on his back. Eventually, the melanoma killed the male teenager and he was farewelled by his friends. Al Bino, however, was portrayed as a popular and positive pale-skinned

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

89

CASE STUDY

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

role model who protected his skin. The five recommended forms of sun protection (using sunscreen, wearing sunglasses and hats, getting under shade, and covering up with clothing) were communicated both visually and lyrically in the video (Cancer Council NSW, 2010). Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer was promoted in Australia over the summer months of December 2008 to March 2009 across multiple media channels, with a focus on social media sites. YouTube, MySpace, and Facebook pages were created to encourage young people to view and share the video and to actively participate in peer-to-peer dialogue. To maintain ongoing communication with the target audience, Al Bino regularly contributed updates to these sites, and conversed with site friends. The social media agency advised CCNSW not to delete or respond to negative comments as this would impact negatively on the integrity of the conversation with young people. The clip was advertised online via video streaming sites and youth-orientated web forums. More traditional media channels, including community service announcements, outdoor billboards, and transit advertising were used to drive the audience to view Al Binos hot new summer track online. The character Al Bino performed live at numerous music events around NSW to large youth audiences, and branded clothing, hats, and stickers were available for purchase online. Finally, a media launch resulted in extensive national and international media coverage, including mainstream television and radio, online news, and music press.

Measures

Three methods were used to measure the process and short-term impact of the intervention, and the extent to which it achieved its objectives.

Process evaluation: Online reach, demographics, social media activity, and media coverage

An external social media agency monitored and measured the online activity to ascertain whether the video captured young peoples attention. Reach and demographics of viewers were tracked through data registered by YouTube members and the social media monitoring tools Radian 6 and Google Insights. Social networking sites were monitored to assess the level of activity and peer-to-peer engagement. The monetary value of editorial media coverage was determined by calculating what it would have cost if it were bought as advertising space or time.

Short-term impact: Online surveys

An external market research company undertook online surveys after the intervention to assess the short-term impact on self-reported sun protection attitudes

90

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

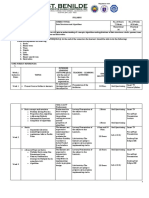

and behaviors. Survey respondents were drawn at random from the research companys database that comprised over 50,000 Australians recruited randomly every year via door-to-door interviewing. The sampling frame for the dataset consists of 552 sampling areas, with each sampling area having approximately equal population size (approximately 30,000 people, aged 14 years and over, based on Australia Bureau of Statistics national data). Clusters of eight interviews were conducted in each of the 550 sampling areas each month, with starting addresses selected at random. Database members were representative of the Australia population aged 14 years and over in terms of gender, age, and geographical location. In April 2009, initial survey invitations were sent to the parents of 1417-year-olds requesting their permission for their children to participate in the survey (n 3,410). Survey invitations were e-mailed directly to 1824-yearolds (n 4,840). All participants were then e-mailed the link to the online survey, which asked about their age, gender, skin type, tanning attitudes, sun protection behaviors, and previous exposure to=awareness of the video clip. This survey process is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Flow Chart of Online Survey Methods

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

91

CASE STUDY

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Participants were asked both open-ended and closed questions to assess differences in sun protection attitudes and behaviors among those exposed to the video and those not exposed to it. Attitude questions included whether they believed there was little chance that they would ever get skin cancer, and whether close friends thought that tanning was a good thing, as an attempt to gauge the influence of peer group or social pressure on attitudes. Participants were also asked if they believed they had the ability to avoid skin cancer by regularly protecting themselves from the sun. Behavioral questions asked participants about the measures that they take to protect themselves from the sun using sunscreen, wearing sunglasses and hats, seeking=getting under shade, and covering up with clothing. Participants aware of the video clip were asked additional questions about their level of engagement and perceptions in response to the video clip. These included how they would describe the video; thoughts prompted by the video and the key message of the video; features of the video they liked; whether they had forwarded on the video to peers or discussed it with them; awareness of sun protection methods used by Al Bino; perceived impact of the video on their own and their friends thoughts and feelings about sun protection; perceptions of self-efficacy in sun protection methods as a result of watching the video; and the likelihood that they would follow these sun protection methods.

Short-term impact: Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted by an external social media agency to determine the key ideas in online dialogue spontaneously prompted by the video and then to analyze these topics in relation to the projects aims. A five-step process was used to monitor, interpret, and understand the nature and sentiment of online conversations (n 1,800) occurring about Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer, which comprised:

1. Selection of related keywords for the search and discovery of online discourse, based on association with the topic area 2. Use of monitoring tools, including Google Alert, Radian 6, and Twitter Advanced Search, to identify instances of discourse occurring and to identify and aggregate online conversations 3. Use of a manual filter of results to gauge origin and relevancy to the subject of interest 4. Analysis of comments, posts, and articles to understand and identify common themes. Individual comments were categorized and grouped into themes. To enable benchmarking against other public health videos, the first 100 comments posted on

92

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

YouTube about Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer and three other public health, youth-targeted videos on YouTube Awareness test (British Road Safety, 2010), Small condoms (Roads and Traffic Authority NSW, 2010), and Teenage affluenza (World Vision, 2010) were analyzed and compared to assess the extent of dialogue focused on behavioral change. Behavior change commentary was identified in relation to each of these videos and the proportion of commentary was then quantified to compare against the Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer clip 5. Analysis of the most effective channels to understand the role of the communication and potential reach within media channels. Statistical analysis

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

The data were subjected to standard quality control procedures and chi-square data analysis was conducted using the research agencys Asteroid software package.

Ethical issues

The codes of professional behavior of the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research and the Australian Market and Social Research Society, and the principles of the National Privacy Act, were adhered to. Results

Process evaluation: Online reach, demographics, social media activity, and media coverage

The video received approximately 250,000 views on YouTube over four months. An estimated minimum of 18% (45,000) of viewers were aged less than 18 years of age. It is possible that this figure could be higher, as there is no age verification requirement for YouTube registrations, and YouTube users under the age of 18 years may overstate their age to enable viewing of restricted online content. Analysis of viewer demographics found that more males viewed the video (65% versus 35% females). An age breakdown of viewers is indicated in Table 1. A total of 46% of views were from Australia, followed by the Middle East, United States, New Zealand, Vietnam, and Austria. Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer was recognized in the YouTube Honours Board in the Australian music category as the most viewed and commented-on video during December 2008. The MySpace page received 74,205 visits and 32,940 video views, and 662 friends posted numerous comments and personal messages. On the Facebook page, 587 friends also posted numerous comments and personal messages, and a user created a Facebook fan group dedicated to Al Bino. Television, press, and radio editorial media coverage was valued at over A$1.2 million.

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

93

CASE STUDY

TABLE 1

Age Breakdown of YouTube Viewers of Its a Beautiful day . . . for Cancer

AGE GROUP (YEARS) TOTAL (PERCENT OF VIEWERS) N 250,000

1324 2534 3554 55

87,500 (35%) 37,500 (15%) 100,000 (40%) 25,000 (10%)

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Short-term impact: Online surveys

Online survey sample

After excluding data from 132 participants who were unsure if they had viewed the video, data from a total of 1,588 participants aged 1424 years were available for analysis. The characteristics of respondents are shown in Table 2. Compared

TABLE 2

Characteristics of Online Survey Respondents

TOTAL (% OF RESPONDENTS) GROUP EXPOSED TO THE VIDEO (% OF RESPONDENTS) N 627 GROUP NOT EXPOSED TO THE VIDEO (% OF RESPONDENTS) N 961

N 1,588

Demographic characteristics (N and % within exposed group vs. unexposed group)

Sex Male Female Age 1417 years 1824 years Skin type

a

593 (37%) 995 (63%)

227 (36%) 400 (64%)

366 (38%) 595 (62%)

656 (41%) 932 (59%)

248 (40%) 379 (60%)

408 (42%) 553 (58%)

Fair=Medium Olive=dark=black Dont know

a

1,200 (76%) 384 (24%) 4

b

467 (74%) 159 (25%) 1

b

733 (76%) 225 (23%) 3b

Response to: How would you describe your skin type when you dont have a tan? Insignificant percentage.

94

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

to the demographic profile of online viewers (35% female), the survey sample had a higher proportion of female (63%) respondents.

Comparison between the exposed and unexposed groups of sun protection attitudes and behaviors

The results are shown in Table 3. There was a significant difference in perceived personal risk of getting skin cancer between the two groups. Participants were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement: There is little chance that Ill ever get skin cancer. A greater proportion of the exposed group (51%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement than the unexposed group (45%) (p .01), which indicated higher levels of perceived personal risk in the exposed group. There were no significant differences in peer perceptions of tanning. Participants were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement: Most of my friends think that a suntan is a good thing; 24% of the exposed group disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement versus 25% (p .691) of the unexposed group. When asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement: If I regularly protect myself from the sun, I can avoid skin cancer, a greater proportion of the exposed group (83%) agreed or strongly agreed than the unexposed group (77%) (p .004), indicating greater confidence in their perceived ability to protect themselves from skin cancer by using sun protection methods. There were also significant differences in self-reported sun protection behavior. Participants were asked: What kind of things, if any, do you do to protect yourself from the sun when outdoors? A greater proportion of the exposed group (88%) reported using sunscreen than the unexposed group (84%) (p .02). Greater proportions of the exposed groups reported use of hats (42% versus 37%) (p .03) and sun-protective clothing (32% versus 27%) (p .04), compared to the unexposed groups. There were no significant differences in reported use of sunglasses or seeking shade to reduce sun exposure.

Engagement and impact among exposed group

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Those participants who had been exposed to the video were asked to assess their engagement with, perceptions of, and impact of the video. Results are shown in Table 4. Communication of the skin cancer prevention message was the predominant take-out for all respondents. One-quarter reported they had either shared or discussed the video with peers. Television was the dominant source of awareness of the online video. The entertainment aspects of the music, lyrics, and humor

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

95

CASE STUDY

TABLE 3

Sun Protection Attitudes and Behaviors Within Exposed Versus Unexposed Groups

GROUP NOT GROUP EXPOSED TO THE VIDEO TOTAL EXPOSED TO THE VIDEO

N 627 (% OF

RESPONDENTS)

N 961 (% OF

RESPONDENTS)

CHI-SQARE VALUE

N 1,588

p VALUE

Number (and proportion) of respondents who believed there is little chance that theyll ever get skin cancer Strongly 270 99 (16%) 171 (18%) 1.08 0.29

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

agree=agree Disagree= Strongly disagree Number (and proportion) of respondents whose close friends thought that a suntan is a good thing Strongly agree=agree Disagree= strongly disagree Number (and proportion) of participants who believed they had the ability to avoid skin cancer by using sun protection Strongly agree=agree Disagree= strongly disagree Number (and proportion) of participants who practised sun protection behavior Sunscreen Hat Clothing Sunglasses Shade 1,356 620 463 341 153 552 (88%) 265 (42%) 201 (32%) 142 (23%) 66 (11%) 804 (84%) 355 (37%) 262 (27%) 199 (21%) 87 (9%) 5.82 4.52 4.22 0.85 0.95 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.357 0.331 105 37 (6%) 68 (7%) 0.85 0.36 1,254 518 (83%) 736 (77%) 8.30 0.004 396 153 (24%) 243 (25%) 0.16 0.691 804 335 (53%) 469 (49%) 3.25 0.072 749 321 (51%) 428 (45%) 6.75 0.01

were identified as the most-liked features. Almost half (44%) of respondents said that the Al Bino video had changed the way they think or feel about sun protection. Over half (52%) thought that the video might change the way their friends feel about sun protection. High levels of perceived self-efficacy for all five

96

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

TABLE 4

Engagement and Impact Among Exposed Group

PROPORTION OF RESPONDENTS INDICATING DOMAIN RESPONSE (OPEN ENDED) RESPONSE (%)

Description of video (open ended)

Song about cancer=sun protection=tanning Funny=enjoyable Gross or disgusting Strange

47 23 15 15 51 14 11 6 6 12

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Nature of thoughts prompted by video (open ended)

Skin cancer or sun damage The need to protect myself Sun protection Dangers of tanning Dislike the music clip General (unrelated to sun protection=tanning)

Features liked about the video (open ended)

Music and tune Lyrics Humor Skin cancer message Other

28 18 12 11 31 25 83 13 11 4 53 53 48 36 7

Peer engagement Source of awareness of Al Bino video

Forwarded=discussed video with peers Television Radio Word of mouth Online

Awareness of sun protection methods used by Al Bino (unprompted, multiple options)

Sunscreen Hats Clothing Sunglasses Shade

(Continued )

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

97

CASE STUDY

TABLE 4

Continued

PROPORTION OF RESPONDENTS INDICATING DOMAIN RESPONSE (OPEN ENDED) RESPONSE (%)

Impact of video on perception of sun protection

Believed video had positive impact on personal thoughts=feelings about sun protection Believed video had positive impact on friends thoughts=feelings about sun protection

44

52

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

Perceived ability to use sun protectiona

Sunscreen Sunglasses Hat Shade Clothing

88 79 73 71 68 62 10

Likelihood to follow recommended sun protection messages

a

Quite=very likely Quite=very unlikely

Proportion responding to question: Please indicate in which of these ways do you feel able to protect yourself from the sun

when you are outdoors?.

sun protection measures were reported. Overall, almost two-thirds (62%) said they were either very likely or quite likely to protect themselves from the sun, as Al Bino did, in the future.

Short-term impact: Thematic analysis

There were 1,800 comments posted online, with the YouTube channel being the largest source of online commentary (50%), followed by online forums (43%) and blogs, Twitter, and responses to online news articles. Analysis found a total of 77% of comments supported the video message and 23% of comments were critical of the video message. Overall, seven key themes emerged:

1. Greater cancer awareness (21% of all comments): Indicated positive support for the cancer awareness message by sharing a personal story associated with the message. For example: Top song mate. Keep them coming. We need to learn to value ourselves and our future. We are not immortal. Thanks for helping to spread the word about cancer (15-year-old male, Australia).

98

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

3. Behavior intention change (19% of all comments): Indicated motivation to have a skin cancer check, to change attitude toward sun protection, to pass the message on to friends, or to take a physical action. For example: Awesome. I am getting a spot checked thanks to you. You scared me into it (under-18-year-old male, location unspecified). 4. Musically appealing (19% of all comments): Enjoyed the hip-hop element of the music. For example: Tune is awesome, lyrics are awesome, this is awesome. Love it! (16-year-old male, Australia). 5. Appreciation (18% of all comments): Nonspecific positive comments directed at Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer. For example: I love this song. I wish I heard it before my cancer scare. You can still enjoy the beach and the sun without having to look like Ken or Barbie while doing it (17-year-old male, Australia). 6. Musically awful (13% of all comments): Didnt enjoy the track and found the music unappealing. Most frequently, these comments came from young male hip-hop music enthusiasts. For example: This Al Bino guy is a huge joke. This song is crap . . . please stop singing on my TV (21-year-old male, Australia). 7. Disturbed (6% of all comments): Found the graphic imagery of the melanoma to be unpleasant. For example: Wow, like the message, has a good beat, good singer, but I will not be sleeping well tonight with the image of a talking mole in my head (15-year-old, gender and location unspecified). 8. Disrespecting cancer (4% of all comments): Regarded the video as insensitive and= or offensive to the condition or individuals who have suffered from cancer. In these cases, the irony of the video was misinterpreted as promoting skin cancer rather than as being an anti-skin cancer message. For example: This video=song should be banned. Imagine if youre suffering from cancer and happen to listen to this poptastic song (23-year-old male, Australia).

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

The behavior intention change dialogue for the Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer video was compared to that generated by three other public health videos: Awareness test (British Road Safety, 2010), Small condoms (Roads and Traffic Authority NSW, 2010), and Teenage affluenza (World Vision, 2010). The Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer video generated stronger dialogue around behavior change (19%) compared to the other videos, which had results ranging from 1% to 5% of dialogue relating to behavior change. Discussion Results from the Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer campaign have highlighted the potential value of using entertaining, peer-to-peer messages to influence youth

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

99

CASE STUDY

attitudes and behaviors (Singhal & Rogers, 1999; Strasburger et al., 2010). The music video captured young peoples attention, reaching over 250,000 views and comparing favourably with other public health campaigns (Roads and Traffic imagery, Authority NSW, 2010; World Vision, 2010). The graphic and risque ironic song title, irreverence, and lack of branding were not without controversy but were ultimately critical to the campaigns success. These factors fueled public intrigue, increased viewership, and encouraged discussion among the target audience, prompting contemplation of skin cancer issues and sun protection, and encouraging dialogue relating to behavior change. Campaign results indicated that those exposed to the video appreciated the humor and shock factor, and still showed a strong understanding of the underlying skin cancer prevention message. Formative research (Potente et al., 2011) and pretesting were critical to ensure that the unconventional strategy was appropriate to engage the target audience. Of the exposed audience, one-quarter reported that they had forwarded or discussed the video with friends, supporting the use of social media channels to enable sharing and peer-to-peer dialogue (Uhrig et al., 2010). Social media does present challenges for specific targeting, as messages cannot be restricted to a specific age group or geographic area. Furthermore, results suggested it is not possible to rely on online strategies alone, as traditional media channels were effective in driving traffic to the online video. In particular, the media launch generated television, press, and radio coverage valued at over A$1.2 million. This combination of online and traditional media maximized the limited budget and provided significant reach and impact. The creative approach was successful in positioning skin cancer as a relevant and important issue. The exposed groups results demonstrated a positive difference in perceived personal risk of skin cancer compared to the unexposed groups. This was reinforced by spontaneous online comments relating to greater skin cancer awareness and acknowledgment of vulnerability to it. A comparison of the two groups highlighted a significant difference in the exposed groups perceived ability to avoid skin cancer by regularly protecting themselves from the sun. High self-efficacy results for the five sun protection measures support this fact, contributing to an overall positive self-reported impact of the video. It was anticipated that the video would have an impact on the social norms around sun protection and tanning. While the campaign results indicated that more than half the viewers believed that the video had a positive impact on their friends thoughts and feelings about sun protection, and 44% believed it had a similar effect on their own, a comparison of responses between the exposed and unexposed groups in relation to peer perceptions of sun tanning preferences

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

100

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

indicated no significant differences. This suggests that an intervention over one summer is unlikely to influence culturally ingrained beliefs and attitudes (Bell, 1992). A majority of viewers of the video reported a high likelihood of using recommended sun protection methods in the future and this was borne out by significant differences between those who were exposed to the video compared to those who were not, in three reported sun protection behaviors. Around 4% to 5% more young people in the exposed group used sunscreen, hats, and clothing compared to the unexposed group. A further 19% of spontaneous online commentary related to intended behavior change, comparing favorably to three other public health online videos (British Road Safety, 2010; Roads and Traffic Authority NSW, 2010; World Vision, 2010). Overall, however, while both the exposed and unexposed groups reported high use of sunscreen, only a relatively low percentage reported using the other four sun protection methods. Of the exposed group, only 42% reported wearing hats, 32% wore protective clothing, 23% wore sunglasses, and just 11% actively decided to seek shade These low scores are at odds with the high self-efficacy scores reported by participants exposed to the video. The scores suggest that entrenched social norms relating to positive perceptions of tanning and concerns that using sun protection (apart from sunscreen) will be perceived negatively, continue to impact young peoples effective use of sun protection (Potente et al., 2011). Future studies are needed to investigate the complex nature of these social norms and the possibility of overcoming this barrier.

Limitations

This study has added to the currently limited body of evidence evaluating the outcomes of health campaigns delivered through social media channels (Uhrig et al., 2010). However, limitations with both the data and impact need to be considered. The sample surveyed did not fully reflect the demographic profile of the population of viewers in terms of gender ratio, possibly reducing the ability to generalize from the results obtained. Another limitation was that although important differences between exposed and unexposed groups were found in perceived risk of skin cancer, perceived ability to avoid skin cancer by using sun protection, and the actual use of several sun protection behaviors, the study did not control for preintervention group differences in attitudes, preferences, and behaviors. Future interventions would require pre and posttesting to further validate the results. Furthermore, the campaign was developed as a communication-only strategy and therefore limited in its capacity to influence long-term behavioral change.

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

101

CASE STUDY

A continuing investment in a comprehensive social marketing strategy may yield effective results for a sustainable improvement in sun protection behaviors.

Implications for social marketing

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

The results of the campaign demonstrate that an innovative promotional strategy can be effective in improving health-related attitudes and behaviors in the short term. A review of the development process identified key lessons that can be used to guide the development of future audience-centric promotional campaigns. The selection of experienced youth communication agencies was critical to the development of the big idea, selection of media channels, and implementation. Research was used to inform strategy development (Potente et al., 2011), and focus testing was used to assess and refine the creative approach and provide reassurance that it would deliver against the campaigns aims. Message tone was critical, with humor and irony successful in engaging youth with a serious health message. To maintain a credible dialogue with a youth audience, it was essential not to heavily moderate the conversation. This included not deleting negative comments and often allowing the online community to correct factually incorrect messages. The study suggested that social media can be used effectively in social marketing campaigns and is an essential tool in the promotional mix when targeting young people. The results and lessons from this campaign have been used to inform the future direction of youth sun protection campaigns at CCNSW. To reduce Australias alarming skin cancer rates, it is critical that social marketers explore new ways to motivate young people to practice effective sun protection. About the Authors Sofia Potente, M.P.H., B. Com. (Marketing and Management), is the Adolescent Campaign Project Officer at Cancer Council NSW. Her area of interest focuses on formative research, planning, development, and evaluation of evidence-based skin cancer-prevention approaches targeting youth. Her experience spans population health research, program evaluation, community education, and health promotion. Sofia is currently on maternity leave. Jackie McIver, B. Bus. (Marketing and Advertising), is the Adolescent Campaign Project Officer at Cancer Council NSW. Her focus is the development, implementation, and evaluation of creative social marketing campaigns to address barriers to skin cancer prevention in young people. Jackie has experience developing targeted communication strategies for travel, fast-moving consumer goods brands, and not-for-profit organizations.

102

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

Caroline Anderson, B.A., Grad. Dip. Sci. (Psych.), is the Evaluation Officer within the Skin Cancer Prevention Unit at Cancer Council NSW. Her focus is evaluating the efficacy of skin cancer programs through the development and implementation of appropriate tools and methods, analysis, and reporting. Her experience includes the implementation and evaluation of cancer-related, public health, and health promotion programs within academic, area health, and not-for-profit environments. Kay Coppa, M.P.H., is the former Manager of the Skin Cancer Prevention Unit at Cancer Council NSW. At the time of the intervention, her role was to implement programs to protect the people of NSW from the harmful effects of UV radiation exposure, to help prevent skin cancer. Kay particularly enjoys exploring relevant and contemporary ways to improve the behavior of populations at risk and making sun protection more accessible. Kay has a background in health promotion and public health. Acknowledgments Cancer Council NSW would like to acknowledge the work and support of Vivid Research, Naked Communications, The Population Social Media Agency, and Roy Morgan Research. This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project Scheme (grant number LP088330) awarded to the Centre for Health Initiatives (UOW) in partnership with Cancer Council NSW. References

Armstrong, B. K. (2004). How sun exposure causes skin cancer: An epidemiological perspective. In D. Hill, M. Elwood & D. English (Eds.), Prevention of skin cancer (pp. 89116). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Australian Communications & Media Authority. (2009). Click and connect: Young Australians use of online social media. Retrieved from http://www.acma.gov.au/WEB/STANDARD/pc=PC_311797 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Association of Cancer Registries. (2007). Cancer in Australia: An overview, 2006. Canberra, Australia: Australia Institute of Health and Welfare. Bell, P. (1992). Multicultural Australia in the media. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Publishing Service. British Road Safety. (2010). Test your awareness: Do the test. Retrieved from http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=Ahg6qcgoay4 Cancer Council NSW. (2008). Its a beautiful day . . . for cancer Al Bino featuring Lyrics Born. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y95qkDC-z-o

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

103

CASE STUDY

Cancer Council NSW. (2010). Be SunSmart. Retrieved from http://www.cancercouncil.com.au/ editorial.asp?pageid=1920 Coogan, P. F., Geller, A., Adams, M., Benjes, L. S., & Koh, H. K. (2001). Sun protection practices in preadolescents and adolescents: A school-based survey of almost 25,000 Connecticut schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 44, 512519. Dixon, H., Borland, R., & Hill, D. (1999). Sun protection and sunburn in primary school children: The influence of age, gender, and coloring. Preventive Medicine, 28, 119130. Dobbinson, S., Wakefield, M., Hill, D., Girgis, A., Aitken, J. F., Beckmann, K., . . . Bowles, K. A. (2008). Prevalence and determinants of Australian adolescents and adults weekend sun protection and sunburn, summer 20032004. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 59, 602614.

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2004). GLOBOCAN 2002. Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide. (Rep. No. cancer base No. 5). Lyon, France: IARC Press. Keshen, A. (2008). Does music affect teens? Can the music youth listen to affect their behavior? Retrieved from http://behavioural-psychology.suite101.com/article.cfm/is_music_for_more_than_ your_ears Livingston, P. M., White, V. M., Ugoni, A. M., & Borland, R. (2001). Knowledge, attitudes and self-care practices related to sun protection among secondary students in Australia. Health Education Research, 16, 269278. Montgomery, K. C., & Chester, J. (2009). Interactive food and beverage marketing: Targeting adolescents in the digital age. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(Suppl. 3), S18S29. Potente, S., Coppa, K., Williams, A., & Engels, R. (2011). Legally brown: Using ethnographic methods to understand sun protection attitudes and behaviours among young Australians I didnt mean to get burntit just happened!. Health Education Research, 26, 3952. Roads and Traffic Authority NSW. (2010). RTA small condom commercial. Retrieved from http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvjBDM-ATWk Schofield, P. E., Freeman, J. L., Dixon, H. G., Borland, R., & Hill, D. J. (2001). Trends in sun protection behaviour among Australian young adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25, 6265. Singhal, A., & Rogers, E. M. (1999). Entertainment-education: A communication strategy for social change. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Strasburger, V. C., Jordan, A. B., & Donnerstein, E. (2010). Health effects of media on children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 125, 756767. Thackeray, R., Neiger, B. L., Hanson, C. L., & McKenzie, J. F. (2008). Enhancing promotional strategies within social marketing programs: Use of Web 2.0 social media. Health Promotion Practice, 9, 338343. Uhrig, J., Bann, C., Williams, P., & Evans, D. (2010). Social networking sites as a platform for disseminating social marketing. Social Marketing Quarterly, 16, 220.

104

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

CASE STUDY

Wilcox, D., & Kanter, B. (2007). Demystifying Web 2.0 for volcom groups: Blogs, rss, tagging, wikis and beyond: Slide set in UK Circuit Rider Conference. Retrieved from http://socialmedia.wikispaces. com/presentation World Vision. (2010). Teenage affluenza. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=KFZz6ICzpjI&feature=PlayList&p=62460088C701D8D4&playnext_from=PL&index=0& playnext=1

Downloaded by [Universidad Del Norte] at 12:50 04 January 2012

SMQ | Volume XVII | No. 3 | Fall 2011

105

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Social Status & Group StructureDocumento12 pagineSocial Status & Group StructureEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- StantonTennRev07 PDFDocumento28 pagineStantonTennRev07 PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Parsons Sistemas SocialesDocumento12 pagineParsons Sistemas SocialesEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Marx South KoreaDocumento8 pagineMarx South KoreaEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Inequality Outcomes Vs Inequality Opportunitie ChileDocumento18 pagineInequality Outcomes Vs Inequality Opportunitie ChileEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- British Empire Liberal MissionDocumento21 pagineBritish Empire Liberal MissionEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Xeno CentrismDocumento5 pagineXeno CentrismEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Menores Quemados PDFDocumento12 pagineMenores Quemados PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 42universitystudents PDFDocumento7 pagine42universitystudents PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis and Social Critique PDFDocumento16 paginePsychoanalysis and Social Critique PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychology Psychiatry PDFDocumento7 paginePsychology Psychiatry PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Psychology Behavioural Ecology PDFDocumento9 pagineHuman Psychology Behavioural Ecology PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Classroom Agression Disruptive PDFDocumento8 pagineClassroom Agression Disruptive PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Elepahnt Classroom PDFDocumento10 pagineElepahnt Classroom PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambios Patron Enfermedad PDFDocumento10 pagineCambios Patron Enfermedad PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 21psychologicalreview PDFDocumento10 pagine21psychologicalreview PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Individualsentinglevelpredictor PDFDocumento14 pagineIndividualsentinglevelpredictor PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Skincancrbrazil PDFDocumento6 pagineSkincancrbrazil PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 21improvesun PDFDocumento10 pagine21improvesun PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 35adolescence PDFDocumento7 pagine35adolescence PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Selfeficcyintegration PDFDocumento21 pagineSelfeficcyintegration PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Regularsunscreenuse PDFDocumento7 pagineRegularsunscreenuse PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 36younadults PDFDocumento6 pagine36younadults PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 30trs PDFDocumento9 pagine30trs PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 25guidelenes PDFDocumento5 pagine25guidelenes PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 34 PDFDocumento10 pagine34 PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of A Multicomponent Intervention On Motivation and Sun Protection Behaviors Among Midwestern BeachgoersDocumento5 pagineEffects of A Multicomponent Intervention On Motivation and Sun Protection Behaviors Among Midwestern BeachgoersEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- 31parents PDFDocumento6 pagine31parents PDFEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- Preventive Medicine: ArticleinfoDocumento5 paginePreventive Medicine: ArticleinfoEl MarcelokoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Data Structures and Algorithms SyllabusDocumento9 pagineData Structures and Algorithms SyllabusBongbong GalloNessuna valutazione finora

- Zkp8006 Posperu Inc SacDocumento2 pagineZkp8006 Posperu Inc SacANDREA BRUNO SOLANONessuna valutazione finora

- STRUNK V THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Etal. NYND 16-cv-1496 (BKS / DJS) OSC WITH TRO Filed 12-15-2016 For 3 Judge Court Electoral College ChallengeDocumento1.683 pagineSTRUNK V THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Etal. NYND 16-cv-1496 (BKS / DJS) OSC WITH TRO Filed 12-15-2016 For 3 Judge Court Electoral College ChallengeChristopher Earl Strunk100% (1)

- Case Study Analysis - WeWorkDocumento8 pagineCase Study Analysis - WeWorkHervé Kubwimana50% (2)

- Name: Mercado, Kath DATE: 01/15 Score: Activity Answer The Following Items On A Separate Sheet of Paper. Show Your Computations. (4 Items X 5 Points)Documento2 pagineName: Mercado, Kath DATE: 01/15 Score: Activity Answer The Following Items On A Separate Sheet of Paper. Show Your Computations. (4 Items X 5 Points)Kathleen MercadoNessuna valutazione finora

- 506 Koch-Glitsch PDFDocumento11 pagine506 Koch-Glitsch PDFNoman Abu-FarhaNessuna valutazione finora

- CCNP SWITCH 300-115 - Outline of The Official Study GuideDocumento31 pagineCCNP SWITCH 300-115 - Outline of The Official Study GuidehammiesinkNessuna valutazione finora

- 24 Inch MonitorDocumento10 pagine24 Inch MonitorMihir SaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Abacus 1 PDFDocumento13 pagineAbacus 1 PDFAli ChababNessuna valutazione finora

- SLTMobitel AssignmentDocumento3 pagineSLTMobitel AssignmentSupun ChandrakanthaNessuna valutazione finora

- Line Integrals in The Plane: 4. 4A. Plane Vector FieldsDocumento7 pagineLine Integrals in The Plane: 4. 4A. Plane Vector FieldsShaip DautiNessuna valutazione finora

- DescriptiveDocumento1 paginaDescriptiveRizqa Anisa FadhilahNessuna valutazione finora

- Wits Appraisalnof Jaw Disharmony by JOHNSONDocumento20 pagineWits Appraisalnof Jaw Disharmony by JOHNSONDrKamran MominNessuna valutazione finora

- Enemies Beyond Character Creation SupplementDocumento8 pagineEnemies Beyond Character Creation SupplementCain BlachartNessuna valutazione finora

- PDFDocumento3 paginePDFvaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Knitting in Satellite AntennaDocumento4 pagineKnitting in Satellite AntennaBhaswati PandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Development of A Small Solar Thermal PowDocumento10 pagineDevelopment of A Small Solar Thermal Powעקיבא אסNessuna valutazione finora

- Snowflake ScarfDocumento2 pagineSnowflake ScarfAmalia BratuNessuna valutazione finora

- Elementary Electronics 1968-09-10Documento108 pagineElementary Electronics 1968-09-10Jim ToewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Applications of Electrical ConductorsDocumento12 paginePractical Applications of Electrical ConductorsHans De Keulenaer100% (5)

- TSC M34PV - TSC M48PV - User Manual - CryoMed - General Purpose - Rev A - EnglishDocumento93 pagineTSC M34PV - TSC M48PV - User Manual - CryoMed - General Purpose - Rev A - EnglishMurielle HeuchonNessuna valutazione finora

- Ezpdf Reader 1 9 8 1Documento1 paginaEzpdf Reader 1 9 8 1AnthonyNessuna valutazione finora

- Eco EssayDocumento3 pagineEco EssaymanthanNessuna valutazione finora

- March 2023 (v2) INDocumento8 pagineMarch 2023 (v2) INmarwahamedabdallahNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocumento18 pagineFinancial Statement AnalysisAbdul MajeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter of Acceptfor TDocumento3 pagineLetter of Acceptfor TCCSNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospectus (As of November 2, 2015) PDFDocumento132 pagineProspectus (As of November 2, 2015) PDFblackcholoNessuna valutazione finora

- Engineering Mathematics John BirdDocumento89 pagineEngineering Mathematics John BirdcoutnawNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011 - Papanikolaou E. - Markatos N. - Int J Hydrogen EnergyDocumento9 pagine2011 - Papanikolaou E. - Markatos N. - Int J Hydrogen EnergyNMarkatosNessuna valutazione finora

- Npad PGP2017-19Documento3 pagineNpad PGP2017-19Nikhil BhattNessuna valutazione finora