Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Analects

Caricato da

anirCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Analects

Caricato da

anirCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Character List

Meng I Tzu/Mang I A young patrician of the state of Lu who was sent to study under Confucius by his father. He died in 481 BC. Meng Wu Po/Mang Wu The son of Meng I Tzu/Mang I. Tzu-yu/Tsze-yu A disciple. Yen Hui/Yan Yuan Confucius's most celebrated disciple and possibly his favorite. His early death caused Confucius some dismay and is mentioned at several points in the text. It is unclear if the statements regarding him preceded his death or were uttered afterwards. Tzu-lu A disciple sometimes referred to as Yu. Tzu-chang/Tsze-chang A disciple. Duke Ai The Duke of Lu from 494-468. Confucius/The Master/Master K'ung A Chinese philosopher, politician, and teacher who lived from 551-479 BC. His philosophy emphasized morality, sincerity, and a mindfulness of the proper way of conducting oneself in all matters. The Analects represent a collection of his sayings as documented by his disciples after his death. Lin Fang A disciple who some scholars believe was known primarily for his slow wit and general lack of intelligence. Jan Ch'iu/Ran Qiu A court minister in service to the Chi family. Confucius asks him if he cannot persuade the family from making offerings on Mount T'ai. He replies that he cannot. Tzu-Hsia/Shang A revered disciple whom Confucius compliments for his grasp of the Book of Songs. Wang-sun Chia The Commander-in-Chief of Wei. Tsai Yu/Zai Yu A disciple of Confucius with whom he expressed great disappointment. He is portrayed in the text as lazy and argumentative at times. Some scholars see Book V, Ch. 9 as evidence that Confucius regretted taking him on as a disciple. Kuan Chung/Guan Zhong A 7th-century BC statesman who built up the power of the Ch'i kingdom. He is regarded as having greatly expanded the political power of the kingdom during his time. Confucius presents an alternative view of him as one who did little to raise the moral status of the kingdom while depriving the Chou king of his rightful power as ruler. Master Tseng

Sometimes called "Zengzi" or "Zeng Shen", this disciple is credited with a number of sayings. He likely became a leader in the Confucian community in Lu and took on disciples of his own, Confucius's grandson among them. Jan Yung/Zhonggong An important Confucian figure who appears to have been well liked and respected by Confucius. See Book VI, Ch. 1. Master Yu/You Ruo This character appears almost entirely in Book I and may have had disciples of his own; it is unclear why he is not quoted more in the other books. Yuan Ssu Little is known of this disciple. It is believed he withdrew from society and lived in Wei following Confucius's death. Ch'i-tiao K'ai/Qidiao Kai This figure only appears once in the text (Book V,Ch. 6), but it is in a positive light. He refuses to seek office after announcing that he has not yet perfected the virtue of good faith. Gongxi Chi/Kung-hsi Hua A native of Lu. It is believed he was chiefly responsible for the rituals conducted at Confucius's funeral. Yan Yan A native of Wu, distinguished for his literary knowledge. Chang/Zi-zhang A native of Chen, believed to be forty-eight years younger than Confucius. Some scholars see disagreement between him and other disciples following Confucius's death. Li/Po-Yu Confucius's son, who is believed to have died before his father. There is little mention of him in the text, though it is clear that his death greatly affected Confucius. Tzu-ch'in A disciple of Confucius. Little is known of him. Yang Huo A retainer for the Chi family, he is believed to have usurped power from the Chi family after being made steward of the domain of Pi. In Book XVII, Ch.1 Confucius seeks to avoid direct contact with such a person but after Yang Huo makes an eloquent statement about the need to serve in government, Confucius agrees to meet him. There is no evidence that Confucius served Yang Huo, however. Kung-shan Fu-jao The Warden of Pi, the chief stronghold of the Chi family. He revolted against the Chi Family in 502 BC. He summons Confucius in Book XVII. Confucius believes Kung-shan may have designs to restore the Duke to his rightful position. Pi Hsi An officer of the Chin. Chieh Yu The madman of Ch'u. Confucius encounters him in Book XVIII and wishes to speak with him but Chieh Yu runs off, making conversation impossible.

About The Analects of Confucius

The Analects of Confucius, Lun Yu, or simply, The Analects, were written about 500 BC and are traditionally attributed to Confucius. However, much of the actual text was written by his students over a time period spanning the thirty to fifty years following his death. The exact publication date of the work is not known. The version that is most well-known today is a combination of the Lu and Qi versions of the work. These were compiled by Zhang Yu, a teacher of Emperor Cheng, towards the end of the Western Han Dynasty. This version came to be known as the Marquis Zhang Analects. The Analects have greatly influenced the moral and philosophical values of China and other countries in Eastern Asia. The text has remained a fundamental course of study for any would-be Chinese scholar for over two thousand years. During the Sui Dynasty, an imperial examination was initiated to test a candidate's ability to apply Confucian philosophy and logic.

Glossary of Terms

Chun-tzu "Son of a ruler"; this term was applied to descendants of a ruling house and came to mean "gentleman". Such a person was expected to behave according to a set of certain moral codes to help them develop te. Hsiao/Xiao This term refers to the virtue of filial piety. Hsin Generally translated as "truth" or "good faith", this term tends to refer to keeping promises and fulfilling obligations. Some scholars feel it should not be mistaken for "telling the truth" but rather as not telling lies that can lead to harm. I Ching Also known as The Book of Changes, it is mentioned at several points in The Analects. The core text is believed to be a collection of Western Chou (Zhou) divine concepts. Confucius is sometimes credited with authoring a commentary on it, although modern textual analysis calls this into question. Jen Difficult to translate accurately, this term is most often presented as "good" or "goodness". It is important to make the distinction that this is not necessarily meant in a descriptive way, but rather as a goal toward which all moral persons should strive. Ju A word of uncertain meaning, it is most often translated as meaning "un-warlikeness" or a "preference for peace or moral force (te)". Legalism A school of political thought that came to suppress much of Confucius's teachings during the Qin or Ch'in Dynasty. Legalism demanded obedience from subjects and any objection to law was met with punishment. Maintenance of power was seen as largely connected to the obedience of those being ruled. Li

Translated as "ritual" this term is of particular importance in The Analects. Li can also refer to something akin to "tradition". Confucian ideals placed great importance on the preservation of old customs and much of the text deals with this concept directly. Lu The name of a state in the southeastern region of China and the place of Confucius's birth. Po This term is usually contrasted with Wang. It translates simply as "elder" or "senior". However, during the Chou dynasty, the term was applied to the senior most feudal lords and later to any ruler who ascended to re-establish the authority of the Chou monarch. A Po was said to be motivated by political gain rather than by moral directive. Shih This word is most often translated as "scholar", though it can also be translated as "knight". Confucius referred to the defenders of the way as "knights", though this was not meant in the warrior or military sense. Shu Ching The Book of History or The Book of Documents; this work includes an Old Text and a New Text and was generally accepted by most scholars until the 17th century, when it was shown that much of the Old Text was forged in the 3rd or 4th centuries. The New Text is generally accepted as being legitimate. Each chapter contains a brief preface, which is generally attributed to Confucius. The chapters chronicle various speeches and prose from the early years of the Chou (or Zhou) Dynasty. Ssu Generally translated as "to think" or "thinking", this term's meaning is a bit difficult to grasp. While Ssu can translate directly as "think", it can also mean "to direct one's attention to" or "observation". In this sense, the term does not refer to an interior cognitive process as much as an external event or impression, which is then replicated in action. T'ien Literally translated as "the sky", most scholars agree that the true equivalent in English would be "Heaven". Tao/Dao The "Way" or "path"; this term is a metaphysical concept that would eventually give rise to a religion and philosophy. In Confucianism, spiritual practice is concerned with becoming aligned with the Tao through moral or meditative practices. The concept ofte, or de, is essential to this realization. Te/De Sometimes translated as "virtue", this term most appropriately means something akin to "character" or "moral force". The Mencius Sometimes known as the Menghzi, this work is a collection of sayings and observations by the Confucian philosopher Mencius. This work is sometimes consulted by scholars in the study of Confucian thought and dogma. The Odes/The Book of Songs A collection of three hundred and five songs and poems dating from the 10th to the 7th Centuries BC. The songs were used in the performance of rituals and rites. Wang

This term translates as "king" but is used in The Analects in a more specific sense. In the text Wang refers to something of a Savior King or True King, one who rules with te. Wei The name of a state in what is the modern Henan province of China. Duke Ling of Wei ruled this state. Wen A complex term with a variety of meanings, wen was originally translated as "markings" or "pattern". The term can also refer to a written character, or to what is decorous, as opposed to plain. In The Analects, the term often refers to matters of culture, specifically literature, and its association with civilization.

Major Themes

Goodness/Humaneness Translated from the word jen or ren, goodness or humaneness is frequently presented in the text as a virtue attained by knowledge and the observation of ritual. It is important to note that the term does not simply mean "good," but speaks to a moral character and attitude that few can hope to possess. It is a complex term outlining a nearly divine presence. As such its attainment can take a lifetime to acquire and years of practiced polishing and re-polishing of one's values and character. The Gentleman or Superior Scholar From the Chinese word Chun-tzu or Junzi, depending on the translation, this term refers to an individual who lives by a refined moral code, follows the Tao, and comes to internalize jen. The life of the "gentleman" is presented in the text as inherently superior in every way to what Confucius comes to refer to as the "small man". This person is not motivated by gain or by a specific political ideology. Rather what is right in every situation is of paramount concern. The life of the gentleman is one of moderation. Any extreme is viewed as incorrect. This theme is mirrored in other works of literature and philosophy. Greek philosophy, for example, prefers the virtue of a middle path between two extremes. Arthur Waley argues that such thinking was also the basis of Liberalism. Rites and Rituals Derived from the term li, rituals and the way of the Ancients, or ancient kings, were of particular interest to Confucius. Li is sometimes better understood as "propriety", as it wasn't specifically limited to the understanding of literal rituals, but also extended to matters of personal conduct. At the heart of this concept is also the idea of knowing the right or just course of action in any situation. Therefore, knowledge of li was directly tied to the accumulation of character and goodness, both characteristics of the Chun-tzu/Junzi. Learning The Analects places an importance on learning but this should not be mistaken for education in the formal sense. While a formal education was certainly valuable, the text seems to place a stress on the continued pursuit of knowledge and wisdom as a means of constantly bettering oneself. Perhaps most egregious in Confucius's eyes was the assumption of knowledge. Confucius is recorded as making several statements on the importance of learning and how a love of learning is one of the hallmark characteristics of the "gentleman". Filial Piety Filial piety, or Hsiao/Xiao, is discussed at some length in The Analects. Confucius saw a duty to one's parents and ancestors as instrumental in the cultivation of virtue and as in

accordance with ritual. It is important to note that this duty was not seen merely as a standard social obligation that had to be carried, however grudgingly. Confucius makes note that anyone can ensure that one's parents have enough food to eat with the same level of attention and care that they may pay to a horse or pet. In dealing with one's parents, filial duty was expected to be carried out with true intent and concern. Government The Analects devotes a good deal of discussion to the topic of government. During Confucius's time much of the power previously limited to kings had become decentralized and was usurped by smaller feudal lords. Confucius advocated for governance through benevolence and placed a great deal of weight on ruling by what was right. A ruler would have to be cognizant of past rituals and traditions but also lead people by example. He should not act out of personal or political gain but instead advocate only for what would be best for his people. Confucius traveled to other kingdoms in the hope of spreading his teachings but did not see their implementation anywhere he went. Rectifying the Names Confucius believed that social order broke down due to a failure to correctly perceive and understand reality. Confucius stressed that the gentleman must use the correct terms and call people, things, and places by their proper names. To do otherwise, he felt, led to a less than thorough understanding of them and this, in turn, led to eventual disorder. Confucius criticized later generations for using terminology that was incorrect or inventing new nomenclature altogether, instead of using the correct terms used by the ancient kings. This theme can be expanded to demonstrate that a clear understanding of all things was the ultimate goal of rectifying the names. It was a tool for best addressing problems and calling something by what it was instead of what one may perceive or wish it to be.

Quotes and Analysis

1. "The Master said, 'At fifteen I set my heart upon learning. At thirty, I had planted my feet firm upon the ground. At forty, I no longer suffered from complexities. At fifty, I knew what were the biddings of Heaven. At sixty, I heard them with docile ear. At seventy, I could follow the dictates of my own heart; for what I desired no longer overstepped the boundaries of right.'" Book II, Ch.4, p. 88 In this quote, Confucius outlines a life devoted to learning and the pursuit of jen. It demonstrates that attaining the status of the "gentleman" or "superior man" is a lifelong pursuit achieved only through a sincere devotion to self-cultivation. This quote also demonstrates that if such devotion is carried out, one can follow his or her heart's desire without concern for moral quandaries, as goodness will then be innate. This quote also presents a small portrait of Confucius himself. It is likely that the quote was transcribed or completed after his death and could be seen as a loving portrait by the disciples of their teacher. 2. "Meng I Tzu asked about the treatment of parents. The Master said, 'Never disobey!' When Fan Ch'ih was driving his carriage for him, the Master said, 'Meng asked me about the treatment of parents and I said, Never disobey!' Fan Ch'ih said, 'In what sense did you mean it?' The Master said, 'While they are alive, serve them according to the ritual. When they die, bury them according to ritual and sacrifice to them according to ritual.'" Book II, Ch. 5, p. 88-89

This quote introduces the topic of filial piety in the text. This quote can be misinterpreted to mean that one should never disobey their parents, but most scholars believe Confucius meant that it was the rituals that should never be disobeyed. The later clarification that Confucius provides to Fan Ch'ih seems to agree with this interpretation. It is also unlikely that Confucius would instruct anyone to obey their parents without regard for what is wrong or right. Even if instructed to do something by a parent, if the task was ethically dubious, Confucius would likely instruct anyone to always remain true to the principles of jen, te, and the Tao. Also, consider that matters of filial duties seem to have been applied to sons only. The Analects does not provide any material that would suggest that Confucius held women in lower regard, but teachings and literature of the time were assumed as the property of men. Although Confucian ideals did argue for some changes in Chinese society, on this matter, they did not conflict with the larger social construct. 3. "Wang-sun Chia asked about the meaning of the saying: Better to pay court to the stove than to pay court to the Shrine. The Master said, 'It is not true. He who has put himself in the wrong with Heaven has no means of expiation left.'" Book III, Ch. 13, p. 97 After finding that he could not reform the politics of Lu, Confucius traveled to other kingdoms in the hopes of presenting his political ideology and having it implemented. In this case, Confucius travled to Wei and met with Wang-sun Chia, the Commander-inChief in the state of Wei. Chia asks if it is not wiser simply to be on good terms with the hearth god and have food than it is to waste food on ancestors who cannot enjoy it. Confucius rejects this concept outright, as we might expect him to given his beliefs and strong feelings about propriety and ancestors. Some scholars also feel that Chia was using this bit of peasant lore to make an analogy about his own power, here represented by the hearth god, vs. the power of the Duke of Wei, here represented by the Shrine. He is suggesting that he is the true seat of power in Wei, and should be treated as such. Likewise, Confucius rejects this assessment, which is consistent with his beliefs. 4. "The guardian of the frontier-mound at I asked to be presented to the Master, saying, 'No gentleman arriving at this frontier has ever yet failed to accord me an interview.' The Master's followers presented him. On going out the man said, 'Sirs, you must not be disheartened by his failure. It is now a very long while since the Way prevailed in the world. I feel sure that Heaven intends to use your Master as a wooden bell.'" Book III, Ch. 24, p. 100 The frontier-mound at I (or Yi in some translations) lay on the border of the state of Wei, where Confucius had traveled but failed to find any interest in his teachings. Upon departing, he is evidently stopped by the keeper of the pass, who tells the disciples that he believes Confucius has been placed here as a "wooden bell". The bell in question refers to a rattle used to alert the populace in times of danger. This quote depicts Confucius as a concentrated effort to re-establish the Way and reintroduce goodness into the kingdoms of China. Remember that the text was established well after Confucius's death and such quotes may have been added to honor or even exaggerate

Confucius's contributions to Chinese society. It is interesting that Confucianism would come to be the official ideology of the state following the abandonment of Legalism. 5. "Tzu-kung said, 'What I do not want others to do to me, I have no desire to do to others.' The Master said, 'Oh Ssu! You have not quite got to that point yet.'" Book V, Ch. 11, p. 110 This quote captures the concept of reciprocity, which is discussed several times in the text. Many scholars compare the quote to the Golden Rule and comment on the near universality of this concept in major world religions. Confucius reprimands Tzu-kung in this quote for not having quite yet achieved the mastery of his own self to be able to make such a statement. Consider the importance of this concept of reciprocity within the larger construct of Confucianism. Benevolence, goodness, and virtue are characteristics that Confucius presented as of the highest importance. In order for a society to function at its moral peak, it would have been important for all its members to extend such respect to one another so that malevolence could not, in theory, become a temptation. 6. "The Master said, 'A horn-gourd that is neither horn nor gourd! A pretty horngourd indeed, a pretty horn-gourd indeed.'" Book VI, Ch.23, p. 120 In this quote Confucius is referring to a particular type of ceremonial bronze goblet, which is written as "horn" next to the term "gourd". The goblet is neither a gourd nor a horn in reality. Confucius uses it as a metaphor to comment on the political state of China. Power in the country at this time was usurped by feudal lords and ministers from kings, hence decentralizing power and leading to what Confucius felt was an erosion of the traditional values and culture of the region. Here, he compares the lords to a pretty object that may shine and sparkle but is not what it appears to be. In other words, such feudal lords may appear to be kings but they are not, and therefore are not the true keepers of the ways of the ancient kings. 7. "Tsai Yu asked saying, 'I take it a Good Man, even he were told that another Good Man were at the bottom of a well, would go to join him?' The Master said, 'Why would you think so? A gentleman can be broken but cannot be dented; may be deceived, but cannot be led astray.'" Book VI, Ch. 24, p. 121 This quote has been interpreted a number of different ways by scholars. Some see Tsai Yu's question as one of insolence and disagreement with Confucius's ideology, while others see it as playful banter. Most feel that this was an indication of some tension between Confucius and Tsai Yu. Confucius responds to Tsai Yu's question with a maxim about the true gentleman, stating that such a person cannot be led to commit wrong acts. Confucius also implies that if one does deceive a gentleman, it does not diminish the stature of the gentleman, but rather exposes the deceiver. This is the "small man" that Confucius speaks of in other parts of the text when comparing the traits of such a person to those of the gentleman.

8. "The Master said, 'How utterly have things gone to the bad with me! It is long now indeed since I dreamed that I saw the Duke of Chou.'" Book VII, Ch. 5, p. 123 The Duke of Chou was a figure revered by Confucius, as indicated by statements in The Analects. The Duke of Chou was said to have saved the dynasty through his wise rule. Some sources also report that he was responsible for devising the rituals of the Chou government. If such reports are to be believed, it is of little surprise that Confucius held this man in high esteem, as these are issues that would have been close to his heart as well. In this quote he again laments the state of government and public affairs in China. His statement can be seen as an indication that he has not seen one such as the Duke of Chou anywhere in recent memory and that he has lost hope of such a figure emerging in politics anytime soon. Indeed the lamentation seems to be a personal reflection on his own state of mind. Confucius regrets having given up hope. 9. "The Master said, 'From the very poorest upwards - beginning even with the man who could bring no better present than a bundle of dried flesh - none has ever come to me without receiving instruction.'" Book VII, Ch. 7, p. 124 Here Confucius comments on the accepting, open nature of his school, where he claims to never turn away anyone for being poor. However, there is disagreement on the translation amongst scholars. This is a common problem with any text whose lineage is so old and which has had the input of several authors. The phrase "bundle of dried flesh" was used to describe school fees after the Han Dynasty and can still be found to mean this in modern China. However, Confucian ideology preceded the Han Dynasty, so it is unclear if the text here is meant to be taken literally as a small offering of meat or idiomatically as a school fee. Cheng Hsuan, a Confucian scholar who lived during the end of the Han Dynasty, believed that the phrase actually means "fourteen years old" or someone who has reached manhood, indicating that as long as a student had reached this age he could be accepted as a student. Given that some pre-Han texts describe small offerings of meat, most scholars believe that this quote should be taken literally. 10."Tzu-lu said, 'If the prince of Wei were waiting for you to come and administer his country for him, what would be your first measure?' The Master said, 'It would certainly be to correct language.' Tzu-lu said, 'Can I have heard you aright? Surely what you say has nothing to do with the matter. Why should language be corrected?' The Master said, 'Yu! How boorish you are! A gentleman, when things he does not understand are mentioned, should maintain an attitude of reserve. If language is incorrect, then what is said does not concord with what was meant; and if what is said does not concord with what was meant, what is to be done cannot be effected. If what is to be done cannot be effected, then rites and music will not flourish. If rites and music do not flourish, then mutilations and lesser punishments will go astray. And if mutilations and lesser punishments go astray, then the people have nowhere to put hand or foot. Therefore the gentleman uses only such language as is proper for speech, and only speaks of what it would be proper to carry into effect. The gentleman, in what he says, leaves nothing to mere chance.'" Book XIII, Ch. 3, p. 172

This quote deals with the concept of the rectification of names, in which Confucius explains that calling things by their proper names is the first step towards maintaining a better society. He establishes a causal relationship, or chain effect, which would lead to a breakdown in social propriety. Many scholars feel this quote was added later in history to the text. They point to the mention of "punishments" in the text, a concept that was never heralded by Confucianism. Some scholars do see a connection between the rectification of names and other Confucian concepts (li for example, in Book III). From this perspective, Confucianism can be seen as something of a holistic philosophy in which all the terms discussed (li, Junzi/Chun-tzu, te, tao) are inter-related and when viewed together present a rounded image of the implicit goals of self-cultivation in each individual and a means to a more just society.

Book II

Summary Book II turns its attention to matters of government. Chapters 1,2, and 3 deal with government issues and the importance of te, or character. Confucius compares the moral leader to one whose character is like the North star. Even as the ethical beliefs of those around such a person may shift, one possessing true character remains steadfast. Likewise, the text stresses the absence of evil or swerving thoughts as paramount in maintaining such character. Chapter 3 echoes Chapter 1 in stating that a moral leader does not use punishment to rule but relies again on the strength of moral character. Simply, rule through force or fear will breed resentment, while governance through character will lead by example. These same ideas are echoed in Chapters 19 and 20. Chapters 6, 7, and 8 return to the topic of filial piety. These chapters also serve to illustrate the rationality involved in matters of deference to one's parents or ancestors. There seems to be an effort to differentiate between a blind acceptance of a set of rules and a true understanding of the logic, or even necessity, of such cultural customs. For example, in Chapter 7 Confucius addresses how a filial son can see to it that his parents have enough food to eat. While that behavior is commendable, the text states that even animals can be cared for to that extent. Without respect and vigilance, there is no difference. Chapter 8 also comments on this difference. Chapters 13-17 appear to deal with a number of philosophical themes and sayings common in early Chinese texts. Chapter 16, for example, is an expression also cited in the Tao Te Ching, and is an often cited verse from the text. The Book ends with statements on both the future or evolution of li as well as the continuing theme of ancestral worship and responsibility. Chapter 23 argues that by examining the path of history, specifically how ritual was observed, one may predict the future. Consider the implication that the fate of a dynasty or culture can be ascertained by observing what it holds important and what is discards from the past. It can also be argued that this passage stresses the importance of foresight. Chapter 24 requires some historical context to be appreciated. In Confucius's time people were only permitted to sacrifice to

their own ancestors and no one else's. Feudal lords were permitted to sacrifice to regional natural spirits, but some presumed sacrificial rights which they had not earned. Analysis Though Book II deals with government, interestingly, the subject of filial piety is visited in this book as well. Consider the duality the text presents in dealing with how one should rule over others while also discussing how one should conduct themselves in deference to their parents. The text seems to imply a parental duty when one is tasked with ruling over others. The word li is generally translated as "ritual" in most versions of the text, but its meaning is likewise difficult to capture completely. Some scholars see its use in The Analects as being akin to tradition, as handed down by divine leadership. The importance of li seems to be tied to the very welfare of the society a ruler governs. To abandon it is to invite tragedy. In this sense, li can be seen as part of the tao/dao, or "Way". Notice that in all passages regarding duties to one's parents the discussion centers only on sons and excludes daughters. Although Confucian texts do not seem to exhibit any decisive prejudice against women, the assumption is that the reader is male. Therefore, in matters of polite or public society, men were still considered the only ones who would need such knowledge. As a result, the text does not escape the social norms of its time. In differentiating between caring for one's parents and one's animals, intent becomes the contrasting element. A "filial son" has only one intention: to ensure that his parents are happy instead of simply having their base needs met. Filial piety is presented as being more than simply serving elders first or undertaking hard work on their behalf. Some scholars see Chapters 13-17 as a kind of commentary by Confucius and his disciples. There are a variety of interpretations on how these verses were to be received. Chapter 16 is an often cited verse from the text. Some scholars feel this chapter extols the virtues of teamwork and communal effort over those of the individual. Others see it as an analogy stating the superiority of a moral way over an opportunistic one.

Book I

Summary With Book I, the text introduces two of the basic themes of the work: what qualities are desirable in a human being and how morality can be reflected in one's behavior. Different translations offer various interpretations of some of the language from the texts, but "virtue" is a recurring quality that is revisited many times. Some translations may introduce the term chun-tzu or junzi, translating as "prince" or "gentleman" respectively. In either case, the terms refer to a person of superior moral character, not necessarily a person of nobility. Some translations present this word as "scholar". The text quickly shifts to matters involving government and family. On the topic of family, the text begins to grapple with the issue of filial piety, or xio. Filial piety refers to the virtue of respect for one's parents or ancestors. In Chapter 6 of Book I, the text presents this sense of duty to one's parents as paramount. Only after one has ensured that their parents are taken care of can they pursue other matters, even if such things are the serious study of literature or other arts. Contrast this chapter with Chapter 7, Book I. Tsze-hsia states that the cultivation of one's character is not solely achieved through academic study but through one's relationships

with others. In his esteem, a person may not be academically inclined but he would still consider them learned. Chapter 7 seems to gently correct aspects of Chapter 6 while echoing much of its content. Ultimately, the impression given is that the content of one's character is a better measurement of a person than his or her status or intellectual acumen. Chapter 8 continues with this theme, adding that a person of moral superiority is not infallible. This person can still make mistakes, but retains his or her standing by making amends for these mistakes immediately. Chapters 11 and 13 continue with the theme of filial piety. Here, the text introduces the concept of reverence for one's parents or ancestors after their death. If a son adheres to his father's path for three years following his father's death, he can be considered filial. It is not clear as to why a period of three years is necessary, or why adhering to the will of one's parents after their death is considered admirable. What is of relevance is that in Confucian ideals such adherence is necessary to fulfill an obligation to one's parents. This passage also implies a reverence for tradition and respect. The concept of Li, sometimes translated as "propriety", is introduced in Chapter 12. In this sense, li can come to mean any pattern of behavior appropriate to the situation. This is discussed specifically with regard to the customs of ancient kings. In Chapter 15, Tsze-Kung remarks on poetry from the Book of Odes. The simile of cutting and polishing is one found throughout Confucian literature. It implies that embodying the ideals presented in the text is a process unto itself in which one should never be fully satisfied. The path, or Tao/Dao, extends forward, so there is always room for further refinement. Chapter 16 echoes elements of Chapter 1 in this book. Analysis One term you may encounter in various translations is jen or ren. This term forms the basis of much of the Analects. Many scholars find this term difficult to translate and there is some disagreement over how best to represent the term in English. Generally, it mostly nearly can be interpreted as "humanity" or "goodness", referring to an inner capacity possessed by all human beings to do good. Some scholars see jen as an embodiment of all the best of human attributes, including piety, honesty, courtesy, and love. Therefore, a person who possesses this attribute can be seen as having a superior moral character. The themes of government and family recur throughout the text. Some scholars see the use of the phrase "the employment of the people at the proper seasons" in Book I, Chapter 5 to coincide with the importance of agriculture in Confucius's time. Farmers were sometimes pulled from the fields during wartime to fight or to participate in public works projects. The text appears to favor a more principled, balanced approach to such affairs, recognizing the importance of allowing crops to be planted and harvested at the proper times and how the production of food affected all the peoples of a region. These characteristics do not paint a portrait of an individual that is above everyday human concerns but who, instead, inhabits his or her humanity to the best of his or her abilities. The text suggests that these philosophical points are not simply rules that should be memorized and followed but are representative characteristics of an individual who pursues the best in himself. In Chapter 12, propriety is contextualized specifically in adherence with the ways and customs of ancient kings, again signaling a reverence for tradition. However, such reverence is not blind devotion to a set of rules. People with knowledge of such customs without a thorough understanding of their subtleties are still considered unlearned.

In both Chapter 16 and Chapter 1, Confucian ideals stress that the pursuit of the admiration of others is not a worthwhile goal. Instead, the betterment of self is achieved through the knowledge and cultivation of the best in others. Consider how this concept can be applied to the fabric of a society. Confucian ideals place the needs of others before the needs of oneself. If everyone in a society practices such diligence, imagine how it would function.

The Analects of Confucius Summary

The Analects of Confucius is an anthology of brief passages that present the words of Confucius and his disciples, describe Confucius as a man, and recount some of the events of his life. The Analects includes twenty books, each generally featuring a series of chapters that encompass quotes from Confucius, which were compiled by his disciples after his death. Book I serves as a general introduction to the various disciples in the work. Book II deals largely with issues of governance. Books III and IV are seen as the core texts, outlining Confucius's ideology. Much of the work concerns itself with the concept of the Tao or the Way, thechun-tzu or the gentleman, Li or ritual, Teor virtue, and Jen or goodness. There are additional terms in the work, but these comprise the core concepts. Taken together they form the backbone of Confucian ideals. The Tao, or the Way, refers to a literal path or road. In the context of the work it refers to the manner in which anything is done; a method or doctrine. Confucius speaks often about the Tao under Heaven, meaning a good way or path to achieving morally superior ends. This could include self-conduct or how a kingdom is ruled. Jen is most often translated as "goodness" or "humanity". The gentleman, or chunt-tzu, possesses this quality. Its translation is a bit difficult to represent exactly in English, but the text provides a good deal of context when discussing the gentleman and goodness. It is helpful not to simply think of the term as meaning "goodness" but also to see how its juxtaposition with the other terms forms a greater picture of how Confucius defined goodness and other positive human qualities. For example, words like "altruistic" or "humane" are useful in understanding this term. Te corresponds most closely to the word "virtue", although you may encounter some disagreement among scholars regarding this translation. A better definition, some scholars say, is to think of it as "character" or "prestige", an attribute that would have been desirable in a human being. The gentleman or chun-tzu is the central term in The Analects and the other terms are generally used in reference to this persona. For this reason it is difficult to summarize the gentleman easily, but considering the term in the light of the other ideas in the text is helpful. The gentleman is one who follows the Way and acts according to a system of morals and beliefs that are not common amongst other individuals. The use of the term "gentleman" to describe the chun-tzu is itself problematic, as it can conjure images related to an aristocratic existence. Some scholars see a similarity between the term and Nietzsche's concept of the Ubermensch, although there is dispute over this idea as well. A "superior man" is another suggested translation of the term. Taken in consideration with the other terms presented, a more complete concept of the chun-tzuemerges. Li, or ritual, is another core concept in the text. Although the work does not go into great detail on what ritual traditions actually entailed, their importance is presented as paramount in the cultivation of te and an understanding of the Tao. The general principles of conduct comprise much of what this term encompasses. Here, moral initiatives outweigh pure

historical knowledge. In other words, practicing what we might call good manners and conducting oneself in a moral and fair affectation were considered characteristic of a gentleman. An appropriate attitude was also necessary: one of reverence and respect for one's elders and for rites and cultural norms that had been handed down by past generations. Also important to consider in reading The Analects is the historical context in which Confucius lived and the events that surrounded his struggle to spread his doctrine. During the Sixth century, powerful warlords and families gained control of the state of Lu, gradually undermining and marginalizing the ducal house. Consequently, the normal structure and function of government and social rituals were altered, much to the dismay of Confucius. Confucius sought a revival of the Chou traditions that once had been the norm in Lu. He saw these ways as legitimately bettering society. The term lifits best in understanding the Chou traditions that Confucius so eagerly wished to reinstate. Eventually, Confucius and his disciples sought an audience with various leaders in Lu to help bring these traditions back. Confucius's plan failed, however, and he left Lu after becoming convinced that the sort of rulers he needed to enlist to his side were not present there. So began a long period of traveling around to neighboring states seeking out such a ruler. Some of this period is captured in the text. Confucius eventually returned to Lu upon the invitation of Jan Ch'iu and lived out his days teaching young men about the Chou traditions. However, he was not able to set up a state based on the teachings he held so dear. The structure of The Analects can make it a difficult work to comprehend. On first reading, the passages can appear to be quite haphazard in their arrangement. From an academic standpoint there is more disagreement than agreement over how best to translate and represent the text for a modern reading audience.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Philosophy: Wise Ideas from Eastern and Western PhilosophersDa EverandPhilosophy: Wise Ideas from Eastern and Western PhilosophersValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (3)

- Maranan, Rhealyn M. (Bayaning Third World)Documento3 pagineMaranan, Rhealyn M. (Bayaning Third World)Rhealyn MarananNessuna valutazione finora

- Rorschach Inkblot Test PDFDocumento11 pagineRorschach Inkblot Test PDFPrateek Kumar PandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Classical Literature Essay 1Documento10 pagineClassical Literature Essay 1Robin LucasNessuna valutazione finora

- Perfection (Ism)Documento9 paginePerfection (Ism)mcdozerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Analects of ConfuciusDocumento7 pagineThe Analects of ConfuciusAnonymous w5cOOIHNessuna valutazione finora

- Aklat NG Mga ArawDocumento7 pagineAklat NG Mga ArawSheila Mae Benedicto50% (4)

- Introduction To World Religions and Belief System ConfucianismDocumento8 pagineIntroduction To World Religions and Belief System ConfucianismVincent AcapenNessuna valutazione finora

- 221st CONFUCIUS MENCIUS AND LAO TZUDocumento6 pagine221st CONFUCIUS MENCIUS AND LAO TZUJulieNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Qin Philosophers and ThinkersDocumento22 paginePre-Qin Philosophers and ThinkersHelder JorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- PresentatuonDocumento67 paginePresentatuonJaikonnenNessuna valutazione finora

- Question # 41Documento10 pagineQuestion # 41Geo Angelo AstraquilloNessuna valutazione finora

- The Analects of Confucius SummaryDocumento3 pagineThe Analects of Confucius SummaryJoshua Paul Ersando100% (1)

- ConfuciusDocumento42 pagineConfuciusLei Marie RalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To World Religion Module 4Documento9 pagineIntroduction To World Religion Module 4James Andre GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucius' Life 2. Confucius' Social Philosophy 3. Confucius' Political Philosophy 4. Confucius and EducationDocumento9 pagineConfucius' Life 2. Confucius' Social Philosophy 3. Confucius' Political Philosophy 4. Confucius and Educationjindalshakshi15Nessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy of ConfuciusDocumento29 paginePhilosophy of ConfuciusYamuna DeviNessuna valutazione finora

- AnalectsDocumento14 pagineAnalectsgeromNessuna valutazione finora

- Intro To World ReportDocumento27 pagineIntro To World ReportElieanne CariasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Book of The DaysDocumento3 pagineThe Book of The DaysCarla Missiona100% (2)

- The Confucian School: Major Thinkers and TextsDocumento11 pagineThe Confucian School: Major Thinkers and TextsLex NgoNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy: History, Background, and Theories from Great ThinkersDa EverandPhilosophy: History, Background, and Theories from Great ThinkersValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (3)

- ConfucianismDocumento5 pagineConfucianismAmelito GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucianism IanDocumento10 pagineConfucianism IanianNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy: A Collection of Idea, Theories, and Ancient WisdomDa EverandPhilosophy: A Collection of Idea, Theories, and Ancient WisdomValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (3)

- The Analects of ConfuciusDocumento1 paginaThe Analects of ConfuciusChristian Paul MacatangayNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucianism (Documento10 pagineConfucianism (sldsjdNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Was Confucius? Ancient China Book for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryDa EverandWho Was Confucius? Ancient China Book for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- ConfucianismDocumento4 pagineConfucianismAngel TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- LESSON 7 - Analects of ConfuciusDocumento6 pagineLESSON 7 - Analects of ConfuciusKhristel AlcaydeNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy: Confucius, Aristotle, Lao-Tzu, and ZenoDa EverandPhilosophy: Confucius, Aristotle, Lao-Tzu, and ZenoValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Tao-Te-Ching: With summaries of the writings attributed to Huai-Nan-Tzu, Kuan-Yin-Tzu and Tung-Ku-ChingDa EverandTao-Te-Ching: With summaries of the writings attributed to Huai-Nan-Tzu, Kuan-Yin-Tzu and Tung-Ku-ChingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2364)

- Chinese LiteratureDocumento7 pagineChinese LiteratureLimuel Andrei LazoNessuna valutazione finora

- Flanagan Confucius and EducationDocumento212 pagineFlanagan Confucius and EducationDavid Carpenter100% (3)

- Confucius (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento16 pagineConfucius (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)bhavikabansal0802Nessuna valutazione finora

- Analects A&H101 VGVDocumento11 pagineAnalects A&H101 VGVMay Artemisia SumangilNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2 - ReligionDocumento4 pagineAssignment 2 - ReligionAndy RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucianism AssignmentDocumento19 pagineConfucianism AssignmentAlphahin 17Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 Section 4Documento5 pagineChapter 4 Section 4api-233607134Nessuna valutazione finora

- ConfucianismDocumento16 pagineConfucianismKimberly Joy IlaganNessuna valutazione finora

- ConfucianismDocumento26 pagineConfucianismNathaniel GaboniNessuna valutazione finora

- Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University Mid-La Union Campus College of Education Laboratory High SchoolDocumento14 pagineDon Mariano Marcos Memorial State University Mid-La Union Campus College of Education Laboratory High Schoolmaryjoy GumnadNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hundred School of Thought - PHEAK SIENGHUODocumento6 pagineThe Hundred School of Thought - PHEAK SIENGHUOSienghuo PheakNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucius by Romeo L. Condicion Jr.Documento15 pagineConfucius by Romeo L. Condicion Jr.ArcieNessuna valutazione finora

- Kong Zi and Lao ZiDocumento28 pagineKong Zi and Lao ZiCyrusNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucianism VasariDocumento28 pagineConfucianism VasariVince Rupert ChaconNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 Chinese Classical LiteratureDocumento3 pagine07 Chinese Classical LiteratureAshwin Hemant LawanghareNessuna valutazione finora

- UnDocumento17 pagineUnMd FahimNessuna valutazione finora

- MaueeDocumento12 pagineMaueemaureentacadaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chinese Historical Background and Its LiteratureDocumento6 pagineChinese Historical Background and Its LiteratureReygen TauthoNessuna valutazione finora

- Great Learning: Book of RitesDocumento2 pagineGreat Learning: Book of RitesDouksieh MikeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sufi Teachings in Neo-Confucian IslamDocumento15 pagineSufi Teachings in Neo-Confucian IslamneferisaNessuna valutazione finora

- All Things PassDocumento4 pagineAll Things Passjessa diane hemotaNessuna valutazione finora

- Confu, Tao, ShintoDocumento7 pagineConfu, Tao, ShintoMrGoNessuna valutazione finora

- Confucianism: Confucius Is Not Just One of The Leading Thinkers in China But in The Whole of AsiaDocumento13 pagineConfucianism: Confucius Is Not Just One of The Leading Thinkers in China But in The Whole of AsiaJulio Hisole Casilag Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Be a Great Thinker Book Five: Confucius - A Scholar, A Statesman and A SageDa EverandBe a Great Thinker Book Five: Confucius - A Scholar, A Statesman and A SageNessuna valutazione finora

- Training Plan - Constantino, RinaDocumento5 pagineTraining Plan - Constantino, RinaanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Did/could The Author/creator Witness/make The Artifact?Documento2 pagineDid/could The Author/creator Witness/make The Artifact?RicalynNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Clean DesignTemplateDocumento6 pagineSimple Clean DesignTemplateanirNessuna valutazione finora

- ENGLISHDocumento6 pagineENGLISHanirNessuna valutazione finora

- 4th QUARTER English 10Documento19 pagine4th QUARTER English 10Jaybert Merculio Del Valle93% (15)

- ENGLISHDocumento6 pagineENGLISHanirNessuna valutazione finora

- TRAINING SESSION EVALUATION FORM - RinaConstantinoDocumento14 pagineTRAINING SESSION EVALUATION FORM - RinaConstantinoanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Tab-Tastic Flat TemplateDocumento8 pagineTab-Tastic Flat TemplateanirNessuna valutazione finora

- The NecklaceDocumento27 pagineThe NecklaceanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Job Description TeacherDocumento3 pagineJob Description TeacherIvy Karen C. PradoNessuna valutazione finora

- Insert Lesson Title Here: StartDocumento11 pagineInsert Lesson Title Here: StartanirNessuna valutazione finora

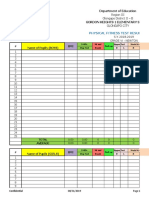

- Fitness Profile Grade 6Documento4 pagineFitness Profile Grade 6anirNessuna valutazione finora

- Main Menu: Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Section 4Documento5 pagineMain Menu: Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Section 4anirNessuna valutazione finora

- Writers in ActionDocumento4 pagineWriters in ActionanirNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd ConvocationDocumento11 pagine2nd ConvocationanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Writers in ActionDocumento4 pagineWriters in ActionanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Warm Philippines Welcome For Trump Amid Improving, Irreversible TiesDocumento5 pagineWarm Philippines Welcome For Trump Amid Improving, Irreversible TiesanirNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.1.1 Local Tour Guiding LessonDocumento16 pagine2.1.1 Local Tour Guiding Lessonanir100% (2)

- Pre TestDocumento6 paginePre TestanirNessuna valutazione finora

- When and How To Include Page Numbers in APA Style CitationsDocumento37 pagineWhen and How To Include Page Numbers in APA Style CitationsanirNessuna valutazione finora

- PT English 6 Q4Documento5 paginePT English 6 Q4anirNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 6 Lesson in EnglishDocumento17 pagineGrade 6 Lesson in Englishanir100% (1)

- 4th Quarter Test in MapehDocumento5 pagine4th Quarter Test in Mapehanir100% (6)

- Mapeh Pre Test-First Sem 2017-2018Documento3 pagineMapeh Pre Test-First Sem 2017-2018anirNessuna valutazione finora

- Writers in ActionDocumento4 pagineWriters in ActionanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Writers in ActionDocumento4 pagineWriters in ActionanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Spelling VocabDocumento15 pagineSpelling VocabanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Spelling Format in PRISAADocumento2 pagineSpelling Format in PRISAAanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 9 Game RelayDocumento10 pagineGrade 9 Game RelayanirNessuna valutazione finora

- Detailed Lesson Plan in English Grade 7Documento5 pagineDetailed Lesson Plan in English Grade 7anir100% (1)

- Dairy IndustryDocumento11 pagineDairy IndustryAbhishek SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Scott CH 3Documento16 pagineScott CH 3RATNIDANessuna valutazione finora

- Project Presentation (142311004) FinalDocumento60 pagineProject Presentation (142311004) FinalSaad AhammadNessuna valutazione finora

- OS W2020 3140702 APY MaterialDocumento2 pagineOS W2020 3140702 APY MaterialPrince PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- DocScanner 29-Nov-2023 08-57Documento12 pagineDocScanner 29-Nov-2023 08-57Abhay SinghalNessuna valutazione finora

- Mapeh Reviewer For My LabidabsDocumento3 pagineMapeh Reviewer For My LabidabsAshley Jovel De GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sibeko Et Al. 2020Documento16 pagineSibeko Et Al. 2020Adeniji OlagokeNessuna valutazione finora

- Marimba ReferenceDocumento320 pagineMarimba Referenceapi-3752991Nessuna valutazione finora

- LivelyArtofWriting WorkbookDocumento99 pagineLivelyArtofWriting Workbookrandles12340% (1)

- Annex E - Part 1Documento1 paginaAnnex E - Part 1Khawar AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Bebras2021 BrochureDocumento5 pagineBebras2021 BrochureJeal Amyrrh CaratiquitNessuna valutazione finora

- Art CriticismDocumento3 pagineArt CriticismVallerie ServanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Highway MidtermsDocumento108 pagineHighway MidtermsAnghelo AlyenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Restaurant Business PlanDocumento20 pagineRestaurant Business PlandavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Eris User ManualDocumento8 pagineEris User ManualcasaleiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Sand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldDocumento2 pagineSand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldAbbas tahmasebi poorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Social Media: AbstractDocumento7 pagineThe Impact of Social Media: AbstractIJSREDNessuna valutazione finora

- Bible QuizDocumento4 pagineBible QuizjesukarunakaranNessuna valutazione finora

- PD10011 LF9050 Venturi Combo Lube Filter Performance DatasheetDocumento2 paginePD10011 LF9050 Venturi Combo Lube Filter Performance DatasheetCristian Navarro AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- Plant-Biochemistry-by-Heldt - 2005 - Pages-302-516-79-86 PDFDocumento8 paginePlant-Biochemistry-by-Heldt - 2005 - Pages-302-516-79-86 PDF24 ChannelNessuna valutazione finora

- Pengaruh Suhu Pengeringan Terhadap Karakteristik Kimia Dan Aktivitas Antioksidan Bubuk Kulit Buah Naga MerahDocumento9 paginePengaruh Suhu Pengeringan Terhadap Karakteristik Kimia Dan Aktivitas Antioksidan Bubuk Kulit Buah Naga MerahDika CodNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpretive Dance RubricDocumento1 paginaInterpretive Dance RubricWarren Sumile67% (3)

- Intel Corporation Analysis: Strategical Management - Tengiz TaktakishviliDocumento12 pagineIntel Corporation Analysis: Strategical Management - Tengiz TaktakishviliSandro ChanturidzeNessuna valutazione finora

- MANILA HOTEL CORP. vs. NLRCDocumento5 pagineMANILA HOTEL CORP. vs. NLRCHilary MostajoNessuna valutazione finora

- V and D ReportDocumento3 pagineV and D ReportkeekumaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Behçet's SyndromeDocumento3 pagineBehçet's SyndromeJanakaVNessuna valutazione finora

- Marcos v. CADocumento2 pagineMarcos v. CANikki MalferrariNessuna valutazione finora

- 10.MIL 9. Current and Future Trends in Media and InformationDocumento26 pagine10.MIL 9. Current and Future Trends in Media and InformationJonar Marie100% (1)

- Problematical Recreations 5 1963Documento49 pagineProblematical Recreations 5 1963Mina, KhristineNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Electronics For RenewablesDocumento22 paginePower Electronics For RenewablesShiv Prakash M.Tech., Electrical Engineering, IIT(BHU)Nessuna valutazione finora