Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Thayer The Philippines Claim To The UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunal: Implications For Viet Nam

Caricato da

Carlyle Alan ThayerTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Thayer The Philippines Claim To The UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunal: Implications For Viet Nam

Caricato da

Carlyle Alan ThayerCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The

Philippines

Claim

to

the

UNCLOS

Arbitral

Tribunal:

Implications

for

Viet

Nam

Carlyle

Thayer

Presentation

to

International

Workshop

on

The

Sovereignty

Over

Paracel

and

Spratly

Archipelagoes

Historical

and

Legal

Aspects

Pham

Van

Dong

University,

Quang

Ngai

City

April

27-28,

2013

The

Philippines

Claim

to

the

UNCLOS

Arbitral

Tribunal:

Implications

for

Viet

Nam

Carlyle

A.

Thayer*

Introduction

This

paper

considers

the

implications

for

Viet

Nam

of

the

Philippines

decision

to

lodge

a

Notification

and

Statement

of

Claim

with

the

United

Nations

(UN)

to

establish

an

Arbitral

Tribunal

to

consider

legal

aspects

of

its

dispute

with

China

in

the

South

China

Sea

(East

Sea

or

Bien

Dong).

This

paper

begins

with

a

brief

overview

of

Chinas

expansion

into

the

South

China

Sea

from

1974

until

the

mid-1990s.

The

paper

then

considers

the

special

case

of

the

Paracel

Islands

that

China

seized

from

Viet

Nam

and

which

remain

a

bilateral

sovereignty

dispute

up

to

the

present.

Next,

the

paper

discusses

Chinese

occupation

of

features

in

the

South

China

Sea

claimed

by

Viet

Nam

and

the

Philippines.

Finally,

the

paper

discusses

the

details

of

the

Philippiness

legal

claim

before

the

United

Nations.

The

conclusions

discuss

the

legal

and

political/diplomatic

implications

for

Viet

Nam

as

well

as

the

prospects

for

a

Code

of

Conduct

for

the

South

China

Sea

(COC).

Paracel

Islands

In

the

mid-1950s

the

Peoples

Republic

of

China

(PRC)

occupied

the

Amphitrite

group

(Nhom

Tuyen

Duc)

in

the

eastern

Paracel

Islands

(Quan

Dao

Hoang

Sa).

With

this

sole

exception

the

PRC

was

not

physically

present

elsewhere

on

features

(islands

or

rocks)

in

the

South

China

Sea

from

1949-1973.

As

late

as

1981,

markers

planted

by

the

Nguyen

Dynasty

(1802-1945)

were

still

observed

by

Vietnamese

fishing

in

waters

around

the

Paracel

Islands.

These

markers

were

later

destroyed

by

Chinese

authorities.1

Since

1973

the

PRC

has

embarked

on

a

prolonged

campaign

to

assert

control

over

the

South

China

Sea

basing

its

claims

to

indisputable

sovereignty

and

historical

rights

on

*

Emeritus

Professor,

The

University

of

New

South

Wales

at

the

Australian

Defence

Force

Academy,

Canberra.

Email:

c.thayer@adfa.edu.au.

Revised

April

30,

2013.

1

Briefing by a Vietnamese fisherman, Ly Son Island, April 28, 2013.

those of its predecessor the Republic of China (ROC). In 2009 China officially tabled a map with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf containing nine- dash lines forming a u-shape enclosing approximately eighty percent of the South China Sea in its ambit claim. Chinas 2009 map was based on one previously issued by the ROC in 1947. New historical evidence seems to indicate that the 1947 map was drawn up by the ROCs Inspection Committee for Land and Water Maps in 1933. Because the Inspection Committee had never carried out and did not have the means to carry out a proper survey it copied existing British Admiralty maps and in doing so carried over cart Errors in the British maps (since corrected) were carried over and incorporated into ROC maps.2 China has never provided a legal clarification of its territorial claims in the South China Sea. Wu Shicun, president of Chinas National Institute for South China Sea Studies, for example, states, [t]he widely held view (in China) is that of a demarcation line for islands. That view holds that all islands lying within the cows tongue [Chinas nine-dash u-shaped line] belong to China, and that China has historical rights, including fishing rights, over the surrounding waters.3 In January 1974, Chinese naval forces engaged and defeated the armed forces of the Republic of Viet Nam (Viet Nam Cong Hoa) and occupied the Crescent groups (Dao Nguyet Thiem) of islands in the western Paracels. In March 1953, the PRC State Council officially established the Guangdong Province-Paracel-Spratly-Macclesfield Bank (Zhongsha) Authority as a county-level administrative unit headquartered on Woody Island (Phu Lam Dao) in the Amphitrite group of the Paracel Islands. In 1984 responsibility for this unit was passed to the Hainan Administrative Region that was upgraded to provincial status in April 1988. In September 1988 the PRC renamed the

Bill

Hayton,

How

a

non-existent

island

became

Chinas

southern

most

territory,

South

China

Morning

Post,

February

9,

2013.

3

Interview with Nozomu Hayashi, Official says Beijing has historical rights over South China Sea, El Bee, January 26, 2012.

Hainan

Administrative

Region

the

Hainan

Province-Paracel-Spratly-Macclesfield

Bank

Authority.

On

June

21,

2012

the

thirteenth

legislature

(3rd

session)

of

Viet

Nams

National

Assembly

formally

adopted

the

Law

of

the

Sea

of

Viet

Nam

(Luat

Bien

Viet

Nam).4

This

law

covered

Viet

Nams

baseline,

internal

waters,

territorial

sea,

contiguous

zone,

exclusive

economic

zone,

continental

shelf,

islands,

the

Paracel

and

Spratly

archipelagos

and

other

archipelagos

under

the

sovereignty,

sovereign

rights

and

jurisdiction

of

Viet

Nam.5

The

law

took

effect

on

January

1,

2013.

Viet

Nams

Law

of

the

Sea

had

been

under

consideration

for

several

years.6

It

was

due

to

be

adopted

in

2011

as

an

assertion

of

Viet

Nams

legal

claims

under

international

law,

including

the

United

Nations

Convention

on

Law

of

the

Sea,

at

a

time

of

rising

tensions

in

the

South

China

Sea.

The

law

was

withheld

so

as

not

to

undermine

the

visit

of

party

Secretary

General

Nguyen

Phu

Trong

to

China

in

October

and

the

return

visit

to

Viet

Nam

by

Vice

Premier

Xi

Jinping

in

December.

Chinese

Embassy

officials

were

aware

that

Viet

Nam

was

drafting

the

Law

on

the

Sea

and

made

representations

urging

Viet

Nam

not

to

proceed.

When

Chinese

officials

were

duly

informed

that

Viet

Nam

intended

to

proceed

it

came

as

no

surprise.

China

prepared

its

response

in

advance.

Chinas

Vice

Foreign

Minister

Zhang

Zhijun

immediately

summoned

Viet

Nams

Ambassador

in

Beijing,

Nguyen

Van

Tho,

to

lodge

a

strong

protest.

At

the

same

time,

Chinas

Foreign

Ministry

issued

a

statement

quoting

the

vice

minister

as

stating,

Viet

Nams

Maritime

Law,

declaring

sovereignty

and

jurisdiction

over

the

Paracel

and

Spratly

Islands,

is

a

serious

violation

of

Chinas

territorial

4

Luat

Bien

Viet

Nam,

the

official

text

in

Viet

Namese

and

an

unofficial

translation

prepared

by

Viet

Nams

Ministry

of

Foreign

Affairs

may

be

found

at:

Carlyle

A.

Thayer,

Viet

Nam

Law

of

the

Sea,

Thayer

Consultancy

Background

Brief,

August

5,

2012.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/101998223/Thayer-Viet

Nam- s-Law-on-the-Sea.

5 6

Luat Bien Viet Nam, Article 1.

It should be noted that in December 2009 the Standing Committee of Chinas National Peoples Congress passed a Law on Sea Island Protection to protect the marine eco-system and promote sustainable development. This law entrenched Chinas sovereignty claims and strengthened the role of the State Oceanic Administration in monitoring compliance.

sovereignty

and

called

for

an

immediate

correction.

China

expresses

its

resolute

and

vehement

opposition.7

Viet

Nams

Ministry

of

Foreign

Affairs

responded

by

issuing

a

statement

that

declared

it

is

regrettable

that

China

reacted

with

unreasonable

criticism

against

Viet

Nams

legitimate

conduct.8

The

statement

drew

attention

to

the

fact

that

the

Law

of

the

Sea

is

the

continuation

of

a

number

of

provisions

of

Viet

Nams

existing

laws.

This

is

not

a

new

matter

Finally

the

statement

reiterated

Viet

Nams

policy

of

settling

difference

and

disputes

in

the

South

China

Sea

by

peaceful

means

on

the

basis

of

international

laws,

including

UNCLOS

and

the

2002

Declaration

on

Conduct

of

Parties

in

the

South

China

Sea

(DOC).

On

June

22,

2012,

the

Foreign

Affairs

Committee

of

Chinas

National

Peoples

Council

approved

a

letter

to

be

sent

to

its

counterpart

in

Viet

Nam,

the

Committee

on

Foreign

Affairs

of

the

National

Assembly.

The

letter

stated

that

Viet

Nams

Law

on

the

Sea

violates

the

consensus

reached

by

both

leaders,

as

well

as

the

principles

of

the

Declaration

on

Conduct

of

Parties

in

the

South

China

Sea.9

Within

hours

of

Viet

Nam

adopting

its

Law

on

the

Sea,

in

a

tit-for-tat

response,

Chinas

State

Council

issued

a

statement

raising

the

administrative

status

of

Sansha

city

from

county-level

to

prefecture

level

with

continuing

jurisdiction

over

the

Paracel

(Nansha)

and

Spratly

(Xisha)

and

the

Macclesfield

Bank

and

surrounding

waters.10

Sansha

City

is

located

on

Woody

(Yongxing)

island

and

has

a

population

of

just

over

1,000

and

an

area

of

13

square

kilometers.

It

has

administrative

responsibility

over

2

million

sq.

km

of

sea.

Both

Viet

Nam

and

the

Philippines

protested

to

China

about

the

elevation

of

Sansha

to

prefecture

level.

Viet

Nam

lodged

a

protest

with

the

Chinese

Foreign

Ministry

claiming,

7

Jane

Perlez,

Viet

Nam

Law

on

Contested

Islands

Craws

Chinas

Ire,

The

New

York

Times,

June

21,

2012

and

Reuters,

China

says

Viet

Nam

claims

to

islands

nuli

and

void,

June

21,

2012.

8

Statement

of

the

Spokesman

of

the

Ministry

of

Foreign

Affairs

of

Viet

Nam,

June

21,

2012,

Embassy

of

the

Socialist

Republic

of

Viet

Nam

in

the

Kingdom

of

Thailand,

June

233,

2012.

9

Xinhua, China urges Viet Nam to correct erroneous maritime law, China Daily, June 22, 2012 Perlez, Viet Nam Law on Contested Islands Craws Chinas Ire.

10

Chinas

establishment

of

so-called

Sansha

City

violated

international

law,

seriously

violating

Viet

Nam

sovereignty

over

the

Paracel

and

Spratly

archipelagos. 11

The

Philippines

handed

a

Note

Verbale

on

June

28

to

Chinas

Ambassador

Ma

Keqing.12

Immediately

after

the

State

Council

announcement,

the

Hainan

province

legislature

made

preparations

to

hold

elections

to

select

Sansha

Citys

first

peoples

committee.

The

elections

were

held

on

July

21

and

45

deputies

were

selected

to

the

municipal

peoples

congress.

The

creation

of

Sansha

City

was

formally

announced

at

ceremonies

held

July

24.

On

June

23,

2012,

two

days

after

the

passage

of

Viet

Nams

Law

on

the

Sea,

Chinas

state-owned

China

National

Offshore

Oil

Company

issued

an

invitation

to

foreign

companies

to

bid

for

nine

offshore

open

blocks

for

exploration

and

development.13

Although

CNOOCs

statement

claimed

that

the

waters

were

under

the

jurisdiction

of

the

PRC,

in

fact

they

were

located

wholly

with

in

the

200

nautical

mile

EEZ

claimed

by

Viet

Nam

under

the

provisions

of

UNCLOS

(but

also

to

eastern

side

of

Chinas

u-shaped

line).14

Luong

Thanh

Nghi,

the

official

spokesperson

for

Viet

Nams

Ministry

of

Foreign

Affairs,

issued

a

formal

protest

on

June

26.

Nghi

called

CNOOCs

offer

illegal

and

a

serious

violation

of

Viet

Nams

sovereignty,

jurisdictional

rights

and

legitimate

national

interests.15

The

next

day

the

General

Director

of

PetroViet

Nam,

Do

Van

Hau,

held

a

11

Agence

France-Presse

and

Associated

Press,

Sansha:

Chinas

newest

toehold

in

disputed

sea,

Philippine

Daily

Inquirer,

July

26,

2012.

12

Michaela

Del

Calla,

PHL

hands

Ma

Keqing

signed

protest

over

Sansha

City,

GMA

News,

July

5,

2012

and

Jim

Gomez,

Philippines

protests

Chinas

establishment

of

a

new

city

claiming

entire

South

China

Sea,

Associated

Press,

July

5,

2012.

13

China

National

Offshore

Oil

Company,

Press

Center

Notification

of

Open

Blocks

in

Waters

Under

the

Jurisdiction

of

the

Peoples

Republic

of

China,

June

13,

2012.

http://en.cnooc.com.cn/data/html/news/2012-06-23/english.322127.html,

14

CNOOC:

Seeking

Foreign

Firms

to

Jointly

Operate

Nine

Offshore

Blocks,

Dow

Jones

Newswires,

June

25,

2012

and

Marianne

Brown,

Tension

Mounts

Between

Viet

Nam,

China,

Voice

of

America,

June

28,

2012.

15

Remark by Viet Namese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Luong Thanh Nghi on June 26, 2012, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mofa.gov.vn/en/tt_baochi/pbnfn/ns120627053317/newsitem_print_preview and Song Yen Ling and Dao Dang Toan, Tensions rise as China offers blocks in waters offshore Viet Nam,

press conference. Hau pointed out these blocks lie deeply on the continental shelf of Viet Nam and overlap with Viet Nams blocks 128 to 132 and 145-156. Hau noted that foreign oil companies were currently operating in those blocks. Indias ONGC Videsh Limited was operating in block 128; Russias Gazprom was operating in blocks 129-133; ExxonMobile was operating in blocks 156-158, and Viet Nams PVEP (PetroViet Nam Exploration Production) was operating in blocks 148-149.16 According to Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt, a Beijing-based analyst with the International Crisis Group, up to June 2012 CNOOC had been unable to obtain approval for exploration in these disputed waters. In her assessment, CNOOC received approval from Chinas top leadership for its actions and this raised tensions to a new level reflecting a change in Chinas policy.17 Laban Yu, an oil and gas analyst with Jeffries Hong Kong, Ltd. offered the view that CNOOCs bidding process had been commandeered by Chinas Ministry of Foreign Affairs to use for political posturing.18 Other analysts noted that CNOOC usually conducted its joint operations with foreign companies in relatively shallow water and its offer of leases in Viet Nams EEZ appeared politically motivated and designed to bolster Chinas territorial claims. 19 Other analysts noted that the location of the bids were more likely to contain gas than oil. Given the low price of natural gas in China, and the distance of these blocks from Chinas mainland, it would not be commercially feasible to construct pipelines. These analysts also concluded that CNOOCs bids were more about politics than about earnings.20

Platts.com

News

Feature,

June

29,

2012.

http://www.platts.com/newsfeature/2012/chinaViet

Nam/index.

16 17

Viet Nam News Agency, PetroViet Nam protests Chinese companys intl oil bidding, June 27, 2012.

Quoted

in

Ben

Bland

and

Gwen

Robinson,

China-Viet

Nam

row

hits

energy

groups,

The

Financial

Times,

June

27,

2012.

18 19

Bland and Robinson, China-Viet Nam row hits energy groups.

Wayne

Ma

and

James

Hookway,

Viet

Nam

Spars

With

china

Over

Oil

Plan,

The

Wall

Street

Journal,

June

27,

2012.

20

Ma and James Hookway, Viet Nam Spars With china Over Oil Plan.

On

July

19,

2012

Chinas

Central

Military

Commission

officially

decided

to

establish

a

military

command

in

Sansha

City.

The

garrison

was

placed

under

the

PLA

Hainan

provincial

sub-command

within

the

Guangzhou

Military

Command.

The

Sansha

military

garrison

would

assume

responsibility

for

national

defence

mobilization,

military

operations

and

reserves.

According

to

Defence

Ministry

spokesperson

Geng

Yansheng,

China

may

set

up

local

military

command

organs

in

the

city

[Sansha]

according

to

relevant

regulations.21

Senior

Colonel

Cai

Xihong

was

appointed

commander

of

the

Sansha

garrison

and

Senior

Colonel

Liao

Chaoyi

was

named

Political

Commissar.22

In

1990

China

constructed

an

airstrip

on

Woody

island

that

can

accommodate

transport

and

fighter

aircraft

such

as

the

Su-27

and

Su-30MKKs.

China

has

also

built

up

the

military

infrastructure

to

include

four

aircraft

hangars,

fuel

depots

and

naval

docks

capable

of

accommodating

frigates

and

destroyers.

Woody

island

also

houses

a

signals

intelligence

(SIGINT)

facility.23

The

standing

up

of

a

military

garrison

on

Woody

Island,

according

to

regional

specialists,

does

not

represent

an

attempt

to

build

a

base

for

forward

deployment

into

the

South

China

Sea. 24

In

their

view,

the

Sansha

military

garrison

is

merely

an

administrative

response

to

the

upgrading

of

Sansha

to

prefecture- level

city.

Military

garrisons

do

not

command

PLA

main

force

combat

units,

PLA

Navy

for

PLA

Air

Force

units.

Spratly

Islands

With

the

exception

of

Itu

Aba

Island

(Taiping

Tao

or

Dao

Ba

Binh/Dao

Thai

Binh)

occupied

by

the

Republic

of

China

(Taiwan)

in

the

1950s,

the

PRC

did

not

have

a

physical

presence

in

the

Spratly

Islands

until

the

late

1980s.

In

March

1988,

Chinese

forces

engaged

naval

forces

of

the

Socialist

Republic

of

Viet

Nam

and

took

control

of

Johnson

21

Xinhua,

Chinese

military

may

establish

presence

in

Sansha:

defense

spokesperson,

Ministry

of

National

Defence

of

the

Peoples

Republic

of

China,

June

28,

2012.

http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/2012- 06/29/content_4381230.htm.

22 23 24

China steps up claims over worlds most disputed waters, National Post, July 27, 2012. J. Michael Cole, China Deploying Military Garrison; to South China Sea?, The Diplomat, July 23, 2012

Dennis J. Blasko and M. Taylor Fravel, Much Ado About The Sansha Garrison, The Diplomat, August 23, 2012.

South (Da Gac Ma) and Fiery Cross (Da Chu Thap) reefs. In late 1994/early 1995 China took control of unoccupied Mischief Reef (Panganiban or Da Van Khan) belonging to the Philippines. China has also occupied McKennan Reef (Chigua), Gaven Reef (Burgos) Subi Reef (Zamora), Johnson Reef (Da Gac Ma), Cuarteron Reef (Bai Chau Vien/Dao Chau Vien) and Fiery Cross Reef. During the early 1990s China and Viet Nam moved to take control of as many of the unoccupied features as they could. Table 1 below sets out the estimated number of features (islands and rocks) occupied (or with territorial markers) by each of the six claimant parties disputing jurisdiction in the South China Sea.

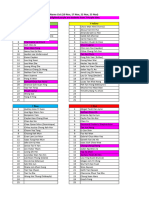

Table 1 Occupation of Features in the South China Sea

In 1992 China awarded the Crestone Oil Company a lease in waters that fell within Viet Nams continental shelf. In 1994, Chinese forces harassed the Vietnamese oil-drilling rig, the Tam Dao, operating in waters around Vanguard Bank (Bai Tu Chinh). In 2011, Chinese civilian maritime enforcement ships began to aggressively harass foreign oil exploration vessels operating in waters claimed by Viet Nam and the Philippines. This resulted in two well-publicized cable-cutting incidents in Viet Nams Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). A third cable cutting incident took place in late 2012. Most recently, Chinese maritime enforcement ships annexed the Philippines Scarborough Shoal (Bajo de

10

Masinloc)

by

erecting

a

barrier

across

the

mouth

of

the

shoal

and

by

maintaining

the

permanent

deployment

of

a

superior

force

of

maritime

enforcement

ships.

In

2011,

Chinese

civilian

maritime

enforcement

ships

began

to

aggressively

harass

foreign

oil

exploration

vessels

operating

in

waters

claimed

by

Viet

Nam

and

the

Philippines.

This

resulted

in

two

well-publicized

cable-cutting

incidents

in

Viet

Nams

Exclusive

Economic

Zone

(EEZ).

A

third

cable

cutting

incident

took

place

in

late

2012.

Most

recently,

Chinese

maritime

enforcement

ships

annexed

the

Philippines

Scarborough

Shoal

by

erecting

a

barrier

across

the

mouth

of

the

shoal

and

by

maintaining

the

permanent

deployment

of

a

superior

force

of

maritime

enforcement

ships.

Chinas

occupation

of

Scarborough

Shoal

was

the

last

straw

and

led

to

the

Philippines

taking

unilateral

legal

action

before

the

UN.

The

Philippines

and

the

Arbitral

Tribunal

UNCLOS

Part

XV

requires

states

to

settle

their

disputes

by

peaceful

means

and

to

exchange

views

towards

this

end.

The

Philippines

argues

that

it

has

continually

exchanged

views

with

China

since

1995

when

China

occupied

Mischief

Reef.

The

Philippines

Notification

and

Statement

of

Claim

concludes,

over

the

past

17

years

of

such

exchanges

of

views,

all

possibilities

of

a

negotiated

settlement

have

been

explored

and

exhausted.

On

January

22,

2013

the

Philippines

therefore

brought

the

matter

before

the

UN.25

On

January

22

Ma

Keqing,

the

Chinese

Ambassador

to

the

Philippines,

was

summoned

to

the

Department

of

Foreign

Affairs

in

Manila

and

handed

a

Note

Verbale

informing

her

that

the

Philippines

was

initiating

a

legal

challenge

to

bring

China

before

an

Arbitral

Tribunal

under

the

terms

of

the

United

Nations

Convention

on

Law

of

the

Sea

(UNCLOS).26

25

Statement

by

Secretary

of

Foreign

Affairs

Albert

del

Rosario

on

the

UNCLOS

Arbitral

Proceedings

against

China

to

Achieve

a

Peaceful

and

Durable

Solution

to

the

Dispute

in

the

WPS,

January

22,

2013.

26

Department of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Philippines, covering letter No. 13-0211 to The Embassy of the Peoples Republic of China, Manila, January 22, 2013 attaching Francis H. Jardeleza, Solicitor General, Republic of the Philippines, Notification and Statement of Claim, January 22, 2013.

11

The

Note

Verbale

contained

the

official

text

of

the

Notification

and

Statement

of

Claim

submitted

to

the

UN

by

the

Philippines.

This

document

outlined

the

Philippine

challenge

to

the

validity

of

Chinas

nine-dash

line

claim

to

the

South

China

Sea.

The

Philippines

also

called

on

China

to

desist

from

unlawful

activities

that

violate

the

sovereign

rights

and

jurisdiction

of

the

Philippines.

Under

UNCLOS

China

had

thirty

days

to

respond

by

notifying

its

nominee

to

the

Arbitral

Tribunal.

On

February

19,

Ambassador

Ma

met

with

officials

at

the

Department

of

Foreign

Affairs

and

returned

the

Philippines

Notification

and

Statement

of

Claim,

thus

rejecting

it.

A

Chinese

Foreign

Ministry

spokesman

in

Beijing

stated

that

the

Philippines

Statement

of

Claim

was

historically

and

legally

incorrect

and

contained

unacceptable

accusations

against

China.27

Under

UNCLOS

Article

287,

a

state

is

free

to

choose

one

or

more

of

four

binding

arbitration

measures:

International

Tribunal

for

the

Law

of

the

Sea

(ITLOS),

International

Court

of

Justice,

Arbitral

Tribunal,

and

a

Special

Arbitral

Tribunal.

If

parties

to

a

dispute

failed

to

issue

a

formal

declaration

specifying

their

choice

of

arbitration,

under

UNCLOS

Article

287(3)

they

shall

be

deemed

to

have

accepted

arbitration

in

accordance

with

Annex

VII.

Because

neither

China

nor

the

Philippines

ever

issued

a

formal

declaration

specifying

their

choice,

their

dispute

became

subject

to

arbitration

by

an

Arbitral

Tribunal.

Every

state

that

ratifies

UNCLOS

is

entitled

to

nominate

four

arbitrators

to

a

list

maintained

by

the

UN

Secretary

General.

An

Arbitral

Tribunal

is

generally

composed

of

five

persons

drawn

from

this

list.

Each

party

to

a

dispute

is

entitled

to

make

one

nomination

and

to

jointly

agree

on

the

other

three

members

including

the

chairman.28

27

Associated

Press,

China

rejects

Philippine

effort

at

UN

mediation

over

South

China

Sea

territorial

dispute,

The

Washington

Post,

February

20,

2013

and

China

rejects

Philippines

submission

on

S

China

Sea,

China.org.cn,

February

21,

2013;

28

The Philippines nominated Rudiger Wolfrum, a German law professor and former president of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. ITLOS President, Judge Shunji Yanai, appointed Polish judge Stanislaw Pawlak to represent China after China failed to nominate by the set deadline. China vs Philippines: Stanislaw Pawlak appointed judge for ITLOS, China Daily Forum, March 26, 2013l

12

Annex VII makes provisions for cases when a state fails to nominate its arbitrator within the thirty-day period. After Chinas rejection the Philippines has two weeks to request the President of ITLOS to make the necessary appointments of arbitrators from the approved list. The President has thirty days to make the necessary appointments. When the Arbitral Tribunal is set up it determines its own procedures. Decisions are made by majority vote. The Arbitral Tribunal may hear the claim made by the Philippines even if China refuses to take part. Under Annex VII, Article 9: If one of the parties to the dispute does not appear before the arbitral tribunal or fails to defend its case, the other party may request the tribunal to continue the proceedings and to make its award. Absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings. Before making its award, the arbitral tribunal must satisfy itself not only that it has jurisdiction over the dispute but also that the claim is well founded in fact and law. The Arbitral Tribunal is required to confine its award to the subject-matter of the dispute and the award shall be final and without appeal It shall be complied with by the parties to the dispute. UNCLOS, however, does not contain any provisions for enforcement. UNCLOS Part XV requires states to settle their disputes by peaceful means and to exchange views towards this end. The Philippines argues that it has continually exchanged views with China since 1995 when China occupied Mischief Reef. The Philippines Statement of Claim concludes, over the past 17 years of such exchanges of views, all possibilities of a negotiated settlement have been explored and exhausted. In August 2006, China made a declaration of optional exceptions exempting itself from compulsory dispute procedures related to sea boundary delimitation (territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf), military and law enforcement activities, and disputes involving the Security Council exercising its functions under the UN Charter. The Philippines was careful in its Notification and Statement of Claim to state it was not seeking arbitration over sovereignty disputes to islands or delimitation of maritime boundaries that China

13

had excluded from arbitral jurisdiction. The Philippines claimed that its maritime disputes with China were about the interpretation and application by States Parties of their obligations under the UNCLOS and therefore could be submitted for resolution. What awards are the Philippines seeking from the Arbitral Tribunal? First, the Philippines sought an award that declared that the maritime areas claimed by China and the Philippines in the South China Sea are those established by UNCLOS and consisted of territorial sea, contiguous zone, EEZ and continental shelf. On this basis, the Philippines requested the Arbitral Tribunal declare that Chinas nine-dash line ambit claim to the South China Sea was inconsistent with UNCLOS and invalid. Further, the Philippines requested that the Arbitral Tribunal require China to bring its domestic legislation into conformity with UNCLOS. Second, the Philippines requested the Arbitral Tribunal to determine the legal status of features (islands, low tide elevations and submerged banks) in the South China Sea claimed by China and the Philippines and whether these features were capable of generating an entitlement of a maritime zone greater than twelve nautical miles. The Philippines specifically listed Mischief Reef, McKennan Reef, Gaven Reef, Subi Reef, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef (Bai Chau Vien/Dao Chau Vien), and Fiery Cross Reef and argued China claimed excessive maritime zones on the basis that these features were islands. The Philippines claimed these features were submerged banks, reefs and low tide elevations that do not qualify as islands under UNCLOS, but are parts of the Philippines continental shelf, or the international seabed. Under UNCLOS islands are entitled to a 200 nautical mile EEZ and rocks to a 12 nm territorial sea. Third, the Philippines argued that China interfered with the lawful exercise of the Philippines rights within and beyond its EEZ and continental shelf in contravention of UNCLOS. The Philippines requested the Arbitral Tribunal require China to desist from (1) its occupation of and activities on the features listed above, (2) interfering with Philippines vessels exploiting the living resources in waters adjacent to Scarborough Shoal and Johnson Reef, (3) exploiting the living and non-living resources within the

14

Philippines

EEZ

and

continental

shelf

and

(4)

interfering

in

the

Philippines

freedom

of

navigation

within

and

beyond

the

200

nautical

miles

of

the

Philippines

baselines.

According

to

an

American

legal

specialist

China

has

four

choices:

First,

China

still

has

an

opportunity

to

change

its

position

and

litigate

the

issues,

or

at

least

to

litigate

whether

the

Arbitral

Panel

has

jurisdiction

over

any

of

the

Philippine

claims

Chinas

second

option

and

perhaps

the

most

likely

is

to

continue

to

refrain

from

participating

and

to

hope

for

a

favorable

outcome.

If

China

loses

the

case,

it

could

declare

the

process

void

and

ignore

its

results

Third,

China

may

believe

its

best

option

is

to

try

to

isolate

and

coerce

the

Philippines

into

dropping

the

arbitration

Finally,

given

the

risks

and

ramifications

of

each

of

these

options,

Beijing

may

decide

to

engage

in

29 quiet

negotiations

with

Manila

to

withdraw

the

case.

China

may

already

be

pursuing

option

three.

Southeast

Asian

diplomatic

sources

have

revealed

that

Beijing

is

putting

diplomatic

pressure

on

ASEAN

states

to

lobby

the

Philippines

to

drop

its

legal

action

with

the

UN

in

return

for

restarting

talks

on

the

COC.30

According

to

Philippine

officials

it

could

take

up

to

three

or

four

years

for

the

Arbitral

Tribunal

to

reach

a

decision.

During

this

time

China

could

further

consolidate

and

expand

its

presence

in

waters

claimed

by

the

Philippines.

Conclusion:

Legal

and

Political/Diplomatic

Implications

What

are

the

implications

for

Viet

Nam

of

the

Philippines

bringing

its

jurisdictional

dispute

with

China

to

the

United

Nations?

On

the

legal

side,

the

Arbitral

Tribunal

could

(a)

reject

the

Philippines

claim

outright

as

having

no

basis

in

international

law

or

rule

that

it

has

no

jurisdiction

in

the

matter;

(b)

take

up

the

Philippine

claim

and

give

an

award

in

favour

of

the

Philippines

on

all

legal

matters

raised;

or

(c)

take

up

the

Philippine

claims

and

award

some

of

the

issues

in

Chinas

favour,

some

of

the

issues

in

the

Philippines

favour

and

decline

to

act

on

some

of

the

legal

issues

raised.

Option

B

is

the

best

result

for

Viet

Nam

because

the

legal

basis

for

Chinas

nine-dash

line

claim

would

be

undermined

if

not

invalidated

in

international

law.

This

would

serve

to

29

Peter

Dutton,

The

Sino-Philippine

Maritime

Row:

International

Arbitration

and

the

South

China

Sea,

East

and

South

China

Sea

Bulletin

[Center

for

a

New

American

Security],

No.

10,

March

15,

2013,

6-7.

30

Based on off-the-record discussions held on March 12-13, 2013.

15

restrain if not prevent China from interfering with oil production and exploration activities in Viet Nams EEZ and continental shelf. The legal classification of islands, rock and other features in the South China Sea would provide the basis for demarcating overlapping maritime jurisdiction under UNCLOS. This would serve to restrain Chinese maritime enforcement ships from operating outside their jurisdiction. Option A is least favourable for Viet Nam because it would undermine the role of UNCLOS in settling maritime jurisdictional disputes. China could be expected to be even more assertive in pressing its claims in the South China Sea. Options B and C could challenge the legal basis for Viet Nams current baselines and claims to low tide elevations in the South China Sea. Viet Nams southeastern baselines known as the pregnant lady are viewed by many legal specialists as excessive and not in accord with international law. With respect to islands, rocks and other features, Viet Nam would have to clarify the status of the features it presently occupies for the purposes of determining maritime jurisdiction. What are the political/diplomatic implications for Viet Nam? Viet Nam must pursue three potentially contradictory political-diplomatic objectives at the same time: show a measure of solidarity with the Philippines, work for ASEAN unity on a Code of Conduct, and ensure its relations with China remain on an even keel. Viet Nam will face difficulties in showing solidarity with the Philippines because of the likely negative consequences for China-Viet Nam relations. Yet failure to show a measure of solidarity with the Philippines may encourage China to isolate the Philippines and further consolidate its presence in the East Sea. Since the Philippines case focuses solely on the Spratly Islands any award by the Arbitral Tribunal will have no major impact on Viet Nams sovereignty dispute with China over the Paracels. This matter can only be settled by direct negotiations by the parties concerned. Finally, what are the implications for ASEANs efforts to negotiate a Code of Conduct with China? The unilateral action by the Philippines to lodge a legal claim with the UN, made without prior consultation with ASEAN members, has raised uncertainty about

16

ASEANs

efforts

to

restart

discussions

with

China

on

a

Code

of

Conduct.31

Diplomatic

sources

in

Southeast

Asia

reported

in

March

2013

that

the

Philippine

actions

have

breathed

all

the

life

out

of

the

COC

process.32

One

think

tank

recently

concluded

that,

Manilas

strategy

might

actually

have

strengthened

Beijings

hand:

its

move

has

undermined

ASESAN

unity

and

risks

negatively

impacting

efforts

to

establish

a

Code

of

Conduct.33

Despite

these

negative

assessments

there

are

some

hopeful

straws

in

the

wind

that

ASEAN

is

renewing

its

efforts

to

engage

China

in

discussions

on

a

Code

of

Conduct.34

In

January

2013,

after

the

ASEAN

Chair

passed

from

Cambodia

to

Brunei,

for

example,

Brunei

and

ASEANs

new

Secretary

General,

Le

Luong

Minh,

both

pledged

to

give

priority

to

reviving

discussions

on

the

COC.35

Bruneis

Sultan

raised

the

COC

issue

with

President

Xi

Jinping

when

they

met

on

the

sidelines

of

the

Boao

Forum

in

April.

Sources

report

that

Brunei

has

set

October

2013

as

a

target

date

for

completion.36

Secretary

General

Minh

asked

Indonesias

President

Susilo

Bambang

Yudhoyono

for

his

assistance

in

addressing

the

South

China

Sea

dispute. 37

Thailand,

as

ASEANs

designated

31

Greg

Torode,

Manilas

lonely

path

over

South

China

Sea,

South

China

Morning

Post,

February

14,

2013

and

Carlyle

A.

Thayer,

China

at

Odds

with

U.N.

Treaty,

USNI

News

[US

Naval

Institute],

March

11,

2013.

http://news.usni.org/2013/03/11/china-at-odds-with-u-n-treaty#more-2251.

32

Based

on

off-the-record

discussions

held

on

March

12-13,

2013.

For

a

pessimistic

view

on

the

prospects

for

a

COC

see:

Ian

Storey,

Slipping

Away?

A

South

China

Sea

Code

of

Conduct

Eludes

Diplomatic

Efforts,

East

and

South

China

Seas

Bulletin,

no.

11,

March

20,

2013.

33

Philippine

legal

move

stirs

South

China

Sea

disputes,

Strategic

Comments

(International

Institute

for

Strategic

Studies),

vol.

19,

April

2013.

34

For

discussion

on

ASEANs

most

recent

draft

COC

and

a

possible

ASEAN

Troika

see:

Mark

Valencia,

Navigating

Differences:

What

the

Zero

Draft

Code

of

Conduct

for

the

South

China

Sea

Says

(and

Doesnt

Say),

Global

Asia,

8(1),

Spring

2013,

72-78

and

Michael

A.

McDevitt

and

Lew

Stern,

Viet

Nam

and

the

South

China

Sea,

in

Michael

A.

McDevitt,

M.

Taylor

Fravel,

Lewis

M.

Stern,

The

Long

Littoral

Project:

South

China

Sea,

CNA

Strategic

Studies,

March

27,

2013,

61-74.

35

New

ASEAN

chair

Brunei

to

seek

South

China

Sea

code

of

conduct,

GMA

News,

14

January

2013;New

ASEAN

chief

seek

to

finalise

Code

of

Conduct

on

South

China

Sea,

Channel

News

Asia,

9

January

2013;

Termsak

Chalermpalanupap,

Toward

a

code

of

conduct

for

the

South

China

Sea,

The

Nation,

22

January

2013,

36 37

Philippine legal move stirs South China Sea Disputes.

Bagus BT Saragih, ASEAN chief pushes RI to act on South China Sea dispute, The Jakarta Post, April 9, 2013.

17

coordinator for dialogue relations with China, also pledged to take up the matter with Beijing.38 When the ASEAN foreign ministers met in Brunei on April 11, Indonesias Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa was quoted as telling reporters that China had requested a special meeting to discuss progress on the Code of Conduct.39 No date was set for the meeting. Other sources report that China did not specifically request a meeting on the COC.40 Foreign Secretary del Rosario, who presented an explanation for his countrys actions in seeking an Arbitral Tribunal, reaffirmed his support for a legally binding COC.41 The ASEAN foreign ministers reiterated their support for a continuing dialogue with China on a South China Sea COC. ASEAN foreign ministers also approved a draft statement on the way forward on the COC drawn up by senior officials. This statement, reportedly, will be issued by the ASEAN heads of government at the 23rd ASEAN Summit to be held from April 24-15 in Brunei.42

38

No

immediate

solution

for

South

China

Sea

dispute:

Shanmugam,

Channel

News

Asia,

14

January

2013;

Thailand

seeks

talks

on

South

China

Sea,

Bangkok

Post,

15

January

2013;

Sihasak

seeks

South

China

Sea

parley,

Bangkok

Post,

25

January

2013

and

Greg

Torode,

Manilas

lonely

path

over

South

China

Sea,

South

China

Morning

Post,

11

February

2013.

39

Agence

France

Presse,

ASEAN,

China

to

meet

on

maritime

code

of

conduct,

The

Economic

Times,

April

11,

2013.

40 41

Private comments made to the author by a reputable journalist, April 17, 2013.

Del

Rosario:

UN

arbitration

on

sea

row

upholds

rule

of

law,

The

Philippines

Star,

April

11,

2013

and

Pia

Lee-Brago,

Phl

to

Asean:

We

need

legally

binding

sea

code,

The

Philippine

Star,

April

12,

2013.

42

Agence France Presse, ASEAN, China to meet on maritime code of conduct, and Asean statement on sea claims up, Manila Standard Today, April 11, 2013. No date was set for the meeting.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Strategic Planning Guidance: Project Manager, Electronic Warfare & CyberDocumento24 pagineStrategic Planning Guidance: Project Manager, Electronic Warfare & CyberZh YunNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cleaning of Prison Station EchoDocumento10 pagineThe Cleaning of Prison Station EchoStan King0% (1)

- Hitler YouthDocumento42 pagineHitler Youthjkjahkjahd987981723Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biography of The Philippine PresidentsDocumento33 pagineBiography of The Philippine PresidentsJordan Ellis94% (33)

- Exemplary Battles of Teh Age of Darkness 30kDocumento15 pagineExemplary Battles of Teh Age of Darkness 30kmillambarNessuna valutazione finora

- RPG-7 Rocket LauncherDocumento3 pagineRPG-7 Rocket Launchersaledin1100% (3)

- Thayer Vietnam - From Four To Two Leadership PillarsDocumento5 pagineThayer Vietnam - From Four To Two Leadership PillarsCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (2)

- Thayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 5Documento3 pagineThayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 5Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 2Documento2 pagineThayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 2Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Welcome To The 10mm Rules Directory!: 1. Use The Same Number of Figures On The Same Size BasesDocumento34 pagineWelcome To The 10mm Rules Directory!: 1. Use The Same Number of Figures On The Same Size BasesJPNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Who Will Be Nguyen Phu Trong's SuccessorDocumento4 pagineThayer Who Will Be Nguyen Phu Trong's SuccessorCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 3Documento2 pagineThayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 3Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer, The Impact of The China Factor On Vietnam's Trade and Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships With The WestDocumento25 pagineThayer, The Impact of The China Factor On Vietnam's Trade and Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships With The WestCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Vo Van Thuong's Resignation Will Throw A Spanner Into Vietnam's Leadership Selection ProcessDocumento2 pagineThayer Vo Van Thuong's Resignation Will Throw A Spanner Into Vietnam's Leadership Selection ProcessCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Consultancy Monthly Report 3 March 2024Documento36 pagineThayer Consultancy Monthly Report 3 March 2024Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Who Is Responsible For Havana Syndrome Attacks On U.S Personnel in Vietnam in 2021Documento2 pagineThayer Who Is Responsible For Havana Syndrome Attacks On U.S Personnel in Vietnam in 2021Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Should The U.S. Sell Weapons To Vietnam's Ministry of Public SecurityDocumento4 pagineThayer Should The U.S. Sell Weapons To Vietnam's Ministry of Public SecurityCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer China's Response To The Vietnam-Australia Comprehensive Strategic PartnershipDocumento3 pagineThayer China's Response To The Vietnam-Australia Comprehensive Strategic PartnershipCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (1)

- Thayer Van Thinh Phat Group and AccountabilityDocumento2 pagineThayer Van Thinh Phat Group and AccountabilityCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Roman Life & Manners Under The Early Empire - Ludwig Friedlander 1913 - Vol 1Documento452 pagineRoman Life & Manners Under The Early Empire - Ludwig Friedlander 1913 - Vol 1Kassandra M JournalistNessuna valutazione finora

- 250 Biet Thu Thao Dien Quan 2Documento16 pagine250 Biet Thu Thao Dien Quan 2Nguyễn Hoài VũNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Why the Dien Bien Phu Victory Led to the Partition of Vietnam at the 1954 Geneva ConferenceDocumento7 pagineThayer Why the Dien Bien Phu Victory Led to the Partition of Vietnam at the 1954 Geneva ConferenceCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Looking Back On The Geneva Agreement, 1954Documento3 pagineThayer Looking Back On The Geneva Agreement, 1954Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Looking Back On The 49th Anniversary of The Fall of SaigonDocumento4 pagineThayer Looking Back On The 49th Anniversary of The Fall of SaigonCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Development and Corruption in VietnamDocumento4 pagineThayer Development and Corruption in VietnamCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Philippines, China and Second Thomas ShoalDocumento2 pagineThayer Philippines, China and Second Thomas ShoalCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Can Vietnam Diversity Arms Procurements Away From RussiaDocumento4 pagineThayer Can Vietnam Diversity Arms Procurements Away From RussiaCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer To Be or Not To Be - Developing Vietnam's Natural Gas ResourcesDocumento3 pagineThayer To Be or Not To Be - Developing Vietnam's Natural Gas ResourcesCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Europe and The South China Sea DisputesDocumento2 pagineThayer Europe and The South China Sea DisputesCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer China, Taiwan and The South China SeaDocumento2 pagineThayer China, Taiwan and The South China SeaCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 1Documento2 pagineThayer Vo Van Thuong Resigns As Vietnam's President - 1Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Personnel Issues Facing Vietnam's Party LeadershipDocumento4 pagineThayer Personnel Issues Facing Vietnam's Party LeadershipCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Vo Van Thuong Resigns As President of Vietnam, Thayer Consultancy Reader No., 12Documento21 pagineVo Van Thuong Resigns As President of Vietnam, Thayer Consultancy Reader No., 12Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 1Documento3 pagineThayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 1Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 3Documento2 pagineThayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 3Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 2Documento2 pagineThayer Australia-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership - 2Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Consultancy Monthly Report 2 February 2024Documento18 pagineThayer Consultancy Monthly Report 2 February 2024Carlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Australia-Vietnam RelationsDocumento2 pagineThayer Australia-Vietnam RelationsCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Thayer Vietnam and ILO Labour RightsDocumento2 pagineThayer Vietnam and ILO Labour RightsCarlyle Alan ThayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Tau List Custom Sept 2000Documento5 pagineTau List Custom Sept 2000Albino SeijoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chinh Thuc TS 1020Documento5 pagineChinh Thuc TS 1020Thu DươngNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Vaksin Peserta Didik TerbaruDocumento5 pagineData Vaksin Peserta Didik Terbaruyasser aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Name ListDocumento5 pagineName ListruhshellhillNessuna valutazione finora

- President Bourguiba Jericho Speech (1965)Documento4 paginePresident Bourguiba Jericho Speech (1965)WajihNessuna valutazione finora

- Battl Efiel D I Nternet: A PL An For Securi NG CyberspaceDocumento8 pagineBattl Efiel D I Nternet: A PL An For Securi NG CyberspaceMehmet Ali ZülfükaroğluNessuna valutazione finora

- GCSE History Scheme of Work Paper 2 Option P4 Superpower Relations v2Documento4 pagineGCSE History Scheme of Work Paper 2 Option P4 Superpower Relations v2fatepatelgaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vol II (E5)Documento261 pagineVol II (E5)nitinNessuna valutazione finora

- Rodolfo El Reno - Violin PartDocumento2 pagineRodolfo El Reno - Violin PartConservatorio RönischNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Law Enforcement AdministrationDocumento17 pagineIntroduction To Law Enforcement AdministrationNovilyn TendidoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gorkhapatra 2080-9-25Documento14 pagineGorkhapatra 2080-9-25Himalayan ParbatNessuna valutazione finora

- NVMVB Avwrryj N Ki Òevsjv 'K: CVWJ Q Eovq ' Wó Govqó: Cökœ Gvov Evsjv 'K P 'B Av BvqviDocumento9 pagineNVMVB Avwrryj N Ki Òevsjv 'K: CVWJ Q Eovq ' Wó Govqó: Cökœ Gvov Evsjv 'K P 'B Av BvqviIstihad EmonNessuna valutazione finora

- Guiuan Rural Health Unit I May23Documento3 pagineGuiuan Rural Health Unit I May23Shana Marie C. GañoNessuna valutazione finora

- List For Unturned Item IDsDocumento33 pagineList For Unturned Item IDsAldy audiwan0% (1)

- Battle of Khyber Historical BackgroundDocumento3 pagineBattle of Khyber Historical BackgroundMalik Aasher AzeemNessuna valutazione finora

- Top Attack - Lessons Learned From The Second Nagorno-Karabakh WarDocumento20 pagineTop Attack - Lessons Learned From The Second Nagorno-Karabakh Wargunfighter29Nessuna valutazione finora

- Armies of The Imperium Box ContentsDocumento1 paginaArmies of The Imperium Box ContentshalldormagnussonNessuna valutazione finora

- 'Omega' SHP-4XDocumento1 pagina'Omega' SHP-4XJhosuan GussoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Documento200 pagineDentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Shivam SNessuna valutazione finora

- Bai Tap Trac Nghiem Menh de Quan He Trong Tieng AnhDocumento10 pagineBai Tap Trac Nghiem Menh de Quan He Trong Tieng AnhTrà My NgôNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategy and Geopolitics of Sea Power Throughout HistoryDocumento214 pagineStrategy and Geopolitics of Sea Power Throughout History伊善强Nessuna valutazione finora