Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Problem of Chinese in The Philippines

Caricato da

profmarkdecenaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Problem of Chinese in The Philippines

Caricato da

profmarkdecenaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Problem of the Chinese in the Philippines Author(s): Russell M'Culloch Story Source: The American Political Science

Review, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Feb., 1909), pp. 30-48 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1945907 . Accessed: 27/04/2013 21:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Political Science Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PROBLEM OF THE CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES

RUSSELL M'CULLOCH STORY

The close of the war with Spain in 1898 and the cession of the Philippinesto the United States broughtto this countrya numberof serious and difficultproblemsin the islands other than those immediatelyconnected with the exercise of governmentalcontrol over them. Not the least among these problemswas that which concernedthe presenceof the Chineseand the question as to their future admissionor exclusion from the islands. An attempted solution was reachedin the extension to the islands in September,1899, of the exclusion laws of the United States. These laws are based upon the limited treaties of 1880 and of 1894, both of which modifiedthe general treaty of 1868. The latter treaty provides for the free admissionof Americansto China and also for the unrestrictedentrance of the Chineseto the United States. At the time of the agitation against the incoming of the Chinesein the seventies, negotiationswere commencedwith Chinawhichin the treaty of 1880 secured her consent for a limited suspensionof the admission rights of the Chineseto the United States. A similarconcessionwas obtained from China in 1894, limited to ten years in its operation. Sincethe expirationof this treaty Chinahas claimedthat the provisions of the treaty of 1868 obtained, while the United States has contended that the treaties of 1880and of 1894 abrogatedthe rights of the Chinese to free admission to United States territory. This contention of the United States is obviously forced and without sufficientbasis either in theory or in fact, and the interpretationis maintainedsolely because of the weakness of China and her inability to prevent the United States from ignoringher protests. This attitude of inattention would hardly be assumedtoward a moreable and aggressivenation. Notwithstandingthese facts it may be assumedthat the sentiment in the United States on the question of Chineseexclusionis so strong that any treaty which provides for the free admission of the Chinesemust

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

31

ultimately be nullifiedin one way or another. But the problemin the Philippinesis a great deal more complicatedif a policy of exclusion is to be carriedout. Such a policy can even be seriously questioned as to its basis in wisdom, equity and necessity, economic or political. Although frequently expelled from the islands by the Spaniardsthe Chinesehad been enjoying comparativefreedom during the last fifty years of Spanish rule. The restrictionswhich were imposed did not constitute any real exclusion. The number of the Chinese in the Philippineshad increasedat a wonderfulrate and their activity had been such as to aid materially in the advancement of the business interests of the archipelago. Hence, when by military order the United States policy of exclusion was made operative in September, 1899, the Chineseminister, Mr. Wu Ting-fang, entered an immediate protest. As early as Februaryof the same year Mr. Wu had inquired of Secretaryof State Hay as to " what policy the United States government intends or is likely to adopt in dealing with the question of Chi" Mr. Wu in this memorandum nese immigrationto the Philippines. pointedout that whilethe treaty of peace had not yet been ratified, the United States was in control; that the trade between China and the Philippines was centuries old and very large; that there were many Chinese in the Philippines as artisans, farmers, traders, merchants, bankers,etc.; that the treaties of 1880 and 1894 relating to exclusion pertainedonly to the North Americancontinent,and there only because of peculiarlabor conditions which did not obtain in the Philippines.' In his protestin SeptemberMr.Wu called attention to the fact that the exclusionwas unwarranted as a militarymeasure;that it was a departure from the announcedpolicyof the presidentto leave the status quo until congressshould determinethe relation of the Philippinesto the United States; and that it was an injusticeto the Chinesesubjectsin the islands and would disturbthe relationsbetween the two governments. Having receivedno reply from SecretaryHay, Mr.Wu protestedagain in Novemberand still againin December,callingparticularattention to the exclusionof merchantsand others of the exempt classes specified dated May 7, 1900,Mr.Wu in the treaty of 1894. In a communication makesthe statement that the presenceof the Chinesein the Philippines

I

See complete correspondence in Document 397, 1st Sess., 56th Cong.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

is indispensableto "the proper development of those islands." He also observedthat this was the unanimoustestimony of Americanand Europeantravelersand students. Apparently,however, the Americangovernmentwas from the first determined on a policy of exclusion. The report of the Schurmann commissionin 1899 stated that the problem of Chinese immigration as affecting commerceand business "is serious and demands consideration." It was also emphasizedthat the natives opposedthe coming of the Chinese.2 In the testimony submittedto this commissionduring its sittings in Manila, Mr. Neil MacLeod, the representative of the London Times,suggestedthat the entranceof the Chinesebe restricted of Mr.GabrielGarciaAgeo, also by meansof a tax.3 The memorandum submitted to this commission, concludes that the Chinese had been unduly protected by Spain to the detriment both of Spain and of the for the Philippines;that the losses to the islandshad been considerable, Chineseconsumedimports from China. He suggested three measures of restriction: first, impose heavy duties on Chinese goods; second, impose heavy duties on opium; and third, prevent the Chinesefrom engagingin agriculture. Mr.Ageo laid stress,however,on the fact that the Chinesefill a need in the Philippines,especiallyin the cities and in "of unhealthy tasks."4 the performance The charges which were urged against the Chinesebeing admitted to the islands and which formedthe basis for the action of the United States military may be summarizedas follows: (1) They remit their earnings to China;5 (2) they practice cheating and deception in trade and business;"(3) they intermarry and ;7 (4) the influence of the Chinese is the halfbreeds are troublesome generally degrading;8(5) the Chinesedo not bring their wives to the islands.9 The dilemma with which the United States governmentfound itself

2 Report of the Schurmann Philippine Commission, vol. i, pp. 150-159. 3 Ibid., vol, ii, pp. 48, 49. 4 Ibid., vol. ii, p. 432 et seq.; p. 444. 5Ibid., p. 17.

61bid., p. 18. 7 Ibid., pp. 187-190; p. 19. 8 Report of the First Philippine Commission, vol. ii, p. 178. 1 Ibid., p. 55.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

33

confronted was a trying one. The one horn consistedof a desire to satisfy the demands of the labor element in this country and of the Filipinosby the adoptionof a policy of exclusion;the other of a demand on the part of contractorsof labor,the Chinesegovernment,the Chinese residents of the islands, and of numeroustravelers in the archipelago for at least a restrictedadmission. It was then generallyadmitted, and is so still, that the free admissionof the Chinesewould greatly hasten the developmentof the islands. But the real issue at stake then and now and the question which must be most fully consideredis whether or not the presenceof the Chineseis essentialto the best development of the Philippines. This is the problem which the United States has tried to solve in adopting the slogan of "The Philippines for the Filipinos." And working on the basis that the islands can be better developed, or at least as well developed,by the Filipinosalone as with the aid of the Chinese,a rigid exclusion policy has been adopted, reinforced by a system of registrationwhich admits of the deportationof all Chinesefound in the islands whose names are not registered. All who enter and leave the islands are accurately measuredand descriptions taken so that evasions of the laws are practically impossible. These measureshave been made possible by three successive steps on the part of the United States: first, the military orderextendingto the Philippinesand enforcingthere the exclusion of the Chineseas in the United States; second, the enactment of congressin 1902 establishing exclusion; and third, the enactment of the Philippine government

in 1903.10

The passage and enforcementof the above laws has not, however, done away with the immense sentiment which favors the admissionof the Chinese to the islands. Consequentlyagitation has not ceased upon the question, and, while the policy of the United States has remainedunchanged,a candid considerationof the problemis timely. One of the first questions which will arise in any discussionis, What has been the recordof the Chinesein the islands? Beforethe American occupationthe recordof arrivalsand departuresof the Chineseshows an increaseof 36,250 in the five years from 1889 to 1893. In the first five years of American occupation from 1899 to 1903 the excess of

10 Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 861.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

arrivals over departureswas but 8624 and this entire excess came in the first three years of the period, the excess of departuresduring the last two years of the period being 122.11 The arrivals have slightly exceeded the departuressince 1903, but the Chinesepopulationin the islands may be said to have become practically stationary by 1901. The census of 1903, published in 1905, shows that there are in the islands 41,035 Chinese,though private estimates go up to 100,000.12 Under Spanishadministrationan effortwas made to admit the Chinese only for purposesof unskilledlabor, the lower kinds of service, and for agriculture. The immigrantswere forbiddento engage in any trade, art, industry, or commercialoccupation. Chinese imported for the raising of tobacco were not taxed. But in 1877 there were only 197 Chinese engaged in agriculture in the islands. In 1879 a Spanish writersays that the Chinamancould at will leave Manilawithout food, light, or clothing,for he had monopolizedall the retail commerce. He also adds that not a Chinamandevoted himself to agriculture.13The fact of the matter seems to be that the history of the Chinamanin the Philippinesis very similarto what it has been elsewhere-he will engage in the lower grades of occupationsonly when forced to do so. Hence the utility of the Chinaman for performing the less desirabletasks in the industrial development of the Philippines may well be questioned. To use him in such lines means the countenancingof contract labor or peonage,both of which would be contraryto the principlesof American administration. However, in work on public improvements such as road building the Chinesehave been extensively used even since the Americanoccupation. Mr.N. W. Holmes, chief engineerof the United States PhilippineCommission in 1902 says that " 1000 Chinamen at one peso per day are worth more than all the labor Luzon could furnishat the rate of board alone."'14 Mr. Robert McGregor,city engineer of Manila,claims that the Chineselaborerwill do 20 per cent more than the Filipino and requireless superintendence.15 Lieutenant J. H. Rice of the ordnance department, U. S. A., states that the Chinese are

11 Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no 58, May 1905, p. 859.

Census of the Philippine Islands, 1905, vol. ii, p. 14. Bulletin of Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 860. 14 Report of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, p. 157. "5Ibid., p. 177.

12 13

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PROBLEM OF THE CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES

35

superiorto the Filipinos in skill, ability and steadiness.", Mr. J. F. Norton, the chief civil engineer,wrote in 1903 that there was no possibility of finishingthe proposedrailroadlines except by the importation of Chineseor other foreignlabor.17 In 1902 GovernorWilliam H. Taft reportedthat the Benguet road engineerand the merchantsof Manila both favoreda foreignlabor supply, inferringthe naturalsourceof such supply, the Chinese.18 The development of the Philippines demands a labor supply and the lack of a sufficientsupply is concededto have retarded and is today retarding the development desired. Chinese coolielabor seems to meet the requirements. But as alreadyexplained the Chinesewill not remain at this labor except by penal contract. They do not even seek it voluntarily because the real wages paid for the lower grades of work performed is no higher in the Philippines than in China.'9 At best it might be a little higher, but would not

serve to attract great numbers of Chinese. However, contract labor

will not be tolerated. Thus with no inducementoffered the Chinese coolie and his being protected from forced labor the prospects of a large influx of this class of Chinese,even were they unrestricted, would not be threatening. Today there are almost none of this type of Chinesein the islands. The position of the Chinamanin relation to agriculturehas been touched upon. The futility of any expectation that the Chinesewill go into agriculture to any great extent is shownin the censusfiguresfor 1905, when of the total Chinesepopulationin the islandsbut 602 could be classed as agriculturalists or 0.048 per cent of the total agricultural population of the archipelago.20Less than 1 per cent of the Chinese were agriculturalists.2' Therefore no plea for the admission of the Chineseas a meansof developingagriculture seems to be well supported by the presentattitude of the Chinesenow in the islandstowardagriculture. In this particularthe facts would seem to warranttheir exclusion, for in reality no injustice is being done to them nor indeed to the interests of the Philippines.

of the Philippine Commission (1902) part i, pp. 257-258. Ibid. (1903), vol. i, pp. 404, 405. "IIbid. (1902), part i, pp. 23, 24. 19 Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 870. 20 Censusof the Philippine Islands, 1905, vol. ii, pp. 894, 895.

17

21

"I Report

Ibid., p. 118.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

36

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

The place occupiedby the Chinesein some of the other walks of life, especially those requiringskill or business ability, is clear. In manufacturingand mechanicalpursuitsthe Chinamanis generallyconceded to be "a more efficient workmanthan the Filipino."22 He excels in shipbuilding, machinery making, repair work, rope making, textile and furnituremaking. Some of these industriessuffer manufacturing, continualdepressionin the Philippinesbecauseof the competitionwith the Chinese, particularlywith Hongkong, Shanghai, and other great Asiatic ports. This competitionmust limit the extent to which manufacturing can be successfullyand profitably carriedon in the islands, even should Chineselabor be freely admitted. Recourse must be had to the aptitude of the Filipinofor machineryand the superiorindustrial organization under American control. Of the present number of Chinesein the Philippinesa total of 6710 are engaged in manufacturing and mechanicalpursuits,which is 0.69 per cent of the total numberof people in the islands engagedin similaroccupations,and 16 per cent of the number of Chinesein the islands.23 Inasmuch as a great many of those in the Filipinorankswho are classifiedunderthis head are women who engagein weaving and other home production,the real importance of the Chinese in the manufacturing and mechanical industries is probablygreaterthan the figureswill actually show. But on the whole their influenceis not of such importanceas to warrantany conclusions as to the necessity of the Chinesefor the best and fullest development of the islands. If the tariff policies of the Philippinegovernmentor of the United States should radically change then the conditions would be altered,but there is little prospectof such an extrememodificationin the situation and hence the tariff policy may be omitted from this

discussion.

Of the Chinese in the islands almost 24 per cent are engaged in domestic and personal service.24 Over 7.2 per cent are cooks. Yet this classificationof Chinesecomprises only 1.7 per cent of the total population engaged in such tasks.25 Their superiorityis hardly ever

22

23

Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, pp. 858, 859. Census of the Philippine Islands (1905), vol. ii, pp. 894, 895. 24 Ibid. Ibid., p. 118.

25

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

37

questioned and they are much preferredto the natives.26 But the demandfor Chinesein personalservice and the degreeof their superiority in such work is not sufficientto warrant either a demand for their free admissionor their exclusion,except as some better reasonmaythus be supplemented. There are eighty-sevenChinesein the Philippines engagedin professional activities, only 0.84 per cent of the total number of persons in such pursuits.27 Thus this sphereof activity may also be eliminatedas a basis for any conclusionsthat they are necessaryfor the best development of the islands. Of the numberof personsengagedin unknownor unproductiveoccupationsthe Chinesefurnishbut 0.04 per cent, which however, was 3.07 per cent of the total Chinesepopulation. But over 55 per cent of this class of Chinesewere women.28 Therefore, so far as these figures mean anything they show that the Chinese are a selfsupportingindependentelement in the population. For the real part played by the Chinesein the economic life of the Philippine Islands one must look at the figures which in the census taken in 1903 are groupedunderthe head of Tradeand Transportation. (See tables, p. 900). Under this division are classified23,364 Chinese, comprising10.26 per cent of the entire numberof those thus occupied.29 As merchants the Chinese stand preeminent, 33.9 per cent of them being so classified,while 14.7 per cent of them are salesmen and 2 per cent are clerks.30 It is suggestedthat the only reason why the Chinaman has so widely gone into commerciallife is becausehe cannot compete with the native labor, especiallythe unskilled workmen. This at least has been inferred from the fewness of the agriculturalworkers after a half century of practicallyunrestrictedadmissionto the islands priorto Americanoccupation.31 The Chinaman is fearedin commercial circles. The census report says that the "Chinamanin Manila, with his gainful instincts, indifference to surroundings, persistence and

28 Mrs. Campbell-Dauncey in her work An English Woman in the Philippines, p. 176, claims that despite Governor Taft's praise for the Filipinos, Mrs. Taft preferred and employed Chinese servants. 27 Census of the Philippine Islands (1905), vol. ii, pp. 894, 895. 28 29

30 31

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 118. Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 869.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

38

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

greaterskill, has always been largely in evidence and ready to compete successfullywith the Filipinos in nearly all trades and drive them to This suggests a occupations of lower and less profitable kinds."232 different idea, viz: that the Chinaman will not compete with the Filipino unskilledlabor because he can do better in commerciallines of

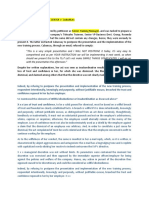

TABLE I.

This table shows the occupations of the Chinese in the Philippines as classified in the Census of 1905.

Per cent of total number i same class.

Male.

Female.

Total.

Agriculture .601 Professional work .86 Domestic and personal .9,696 Trade and transportation .23,330 Manufacturing and mechanical .6,670 Unknown or unproductive .688 Cf. Philippine Census, vol. ii, pp. 894-5.

TABLE II.

1 1 107 34 40 843

602 87 9,803 23,364 6,710 1,531

0.048 0.34 1.70 10.26 0.69 0.04

This table shows the total number of natives and of Chinese in the different occupations.

Natives. Chinese.

Agriculture ........................................... Professional work ..................................... Domestic and personal ................................. Trade and transportation ............................... Manufacturing and mechanical .......................... Cf. Philippine Census, vol. ii, pp. 894-5.

1,162,108 21,155 420,044 120,004 234,970

601 86 9,696 23,330 6,670

activity. An Americanlumber merchantis opposed to the admission of the Chinese, saying, "They drive Americans out of business."33 Even an European mercantileemployer of labor on a large scale says, "As to Chinese, so long as they are allowed in the country only as

32

33Bulletin

Census of the Philippine Islands (1905), vol. iv, p. 432. of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 865.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

39

laborers,it might not be so bad; but if they are to go into business, like they do now, as soon as they have saved a little money it wouldbe a very

bad thing."234 Another American merchant says,

". . . .

if the

Chineseare allowed,they might drive all the Americanshere out of the "Y35 When these statements are considered islandsby their competition. the animusfor the exclusionof the Cihnesefrom a commercialpoint of view becomesmore evident. In ManilatheRozario,a broadstreet and is occupied chiefly by Chineseshops one of the principalthoroughfares, and is a busy place.36 The principaltraders in Iloilo, the second seaport in the islands in importance, are Chinese or Chinese mestizos.37 betweenthe foreignmerchantsand The Chineseformthe intermediaries the natives, being trusted by the latter.38 By means of bamboofreight boats the Chinese are able to reach far into the interior with their commerce. The manner in which they have won the confidence of those with whom they deal has been one of the chief sources of their success.39 The fact of the matter is that the Chinamanthreatens, in the Philippinesas in other parts of the Orient,to becomethe master of the entire field of trade and transportationexcept in so far as he is restricted from so doing. This dominance is what is really feared. Coupledwith the prejudice against the Chinese in the United States, the hatred felt by the high class Filipinos toward him because of his commercialsuperiorityhas led to the extension of the exclusion laws to the islands and to their being made even more strict than in this country. Whether or not this exclusionis justifiablecannot, however, be fully determineduntil other factors are taken into consideration. The place of the Chinamansocially and as a citizen is important in determininghis claim for free admissionto the Philippines. Is he a desirableaddition to the elements of populationthere? As a rule the Chinamanis content to leave political life alone as long as he is permitted to make a livelihood on an equality with others. The Chinese

34 3 36 37 38

Ibid., pp. 862, 863.

Ibid., p. 863. Directory of China, Japan, the Philippines, etc. (1898), p. 499.

Ibid., p. 531.

Census of the Philippine Islands, vol. i, p. 39. Also Bulletin of Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 858. 39H. M. Wright, Handbook of the Philippines, pp. 218, 219. 40 F. W. Atkinson, The Philippine Islands, pp. 261-263.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

40

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

will even submit to many repressive measures and not complain. They do not aim at citizenship as we understand that term in the United States. In the Philippines the Chinese are after profits primarily. They do, however, make homes and mingle freely with the Filipino races. Marriageswith Filipino women are frequent. In fact the Chineseare often preferredas husbands. They make more money, are liberalwith it.to their families,and they are soberand industrious.40 But in general the Chinesereturn to China to spend the profits they have accumulatedin the islands, leaving no social impress upon the communityin which they have lived except a negative one, unless the conclusion be accepted that the teaching of such habits as gambling, adulteration of goods, etc., constitute such an impression. In part this failure of the strongerrace to greatly influencethe weaker is due to the early and continued contact of the Filipinos with Europeans.4 Among the elements of the problemwhich requireconsiderationare the racial differencesand capacities of the Chineseand the Filipinos. The Chineseare describedas frugal,industrious,persistent;the Malays and the Spanishas not S0.42 The contention is urged that the Filipino race is weak and lacking in virility. Thus stimulus is needed which

will.43 but whichthe Chinese willnot supplyby marriage, the American

The Chinamenof the Philippinesare differentfromthose of the laundry classin the United States. They can readand write.44 "It mustbe tantalizing for the keen, industriousChineseto be almost on the soil of The Chinese this Eldoradoof lazy natives and high wages. writes one observerin make their own and their employers'fortunes," describingthe precautionstaken and in criticizingthe mannerin which the crews of the Chinesevessels are guardedto prevent their landingin the islands.45 The Chinesecoolies never refuse work, are reliable,and never complain,is the testimony of another.46 The Chinaman"does not build up industriesnor introduceimprovements. He is a reactionary rather than a progressivecharacter in both an industrial and a

41 42 43 44 45 46

J. A. LeRoy, Philippine Life in Town and Country, pp. 36-38. A. J. Brown, New Era in the Philippines, p. 79. Ibid., pp. 82-87.

Ibid., p. 80.

An English IWomanin the Philippines, p. 176. New Era in the Philippines, p. 34.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

41

civic sense. . . . . The Chineseopposeswhilethe Filipinowelcomes the introduction of labor saving machinery."47 The Chinese cannot give incentive and initiative to the working people for they "do not "48 Such are some of the possess the progressivequalitiesthemselves. varying estimates of the Chineseas workingmenand as citizens in the economic and political life of the people of the Philippines. Similar divergencesin the estimates of the abilities and characteristicsof the Filipinos are prevalent. "The Filipino is ready to adopt new ways of doing things."49 The native labor is indolent and its efficiency lessened by a propensity to gamble.50 The Filipinos are "ready to "I' " OurFilipinoshave been faithful, workfor a sufficientinducement. without bad habits prejudicialto their integrity." They have made extraordinary progress in the industrial virtues.52 The Filipino possesses "very little saving instinct."53 "It only requires a little diplomacy to make these people (Filipinos) industrious."54 All witnesses agree that the Filipino has a great knack of imitation and aptitude for handlingnew kinds of machinery,etc. One employeraccuses the Filipinosof beingshirkful,sly, deceitful,devoid of energy,preferring lying to telling the truth, ignorant, lazy and lacking in judgment.55 Anotherspeaks of them as without skill or desireto become skilled, as not efficient, systematic, rapid or trustworthy, and as hard to teach these qualities.56 The variety of testimony consideredseems to justify almost any conclusion. Much more could be offered,about half of it favorableand the rest unfavorableto the Filipino. One thing must be noted-the harshest words against the Filipino come from United States army engineers,men of army trainingand used to handlingmen in industryas soldiersare handled. Wherethe native has been studied, his peculiarities him as a and demandsconsidered, the wordsconcerning

47 48 49

Bulletin of Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 862. Ibid.

Ibid. Ibid., p. 864. 51 Ibid., p. 866. 52 Ibid.

50

54

Ibid., p. 867. Ibid., p. 868. 55 Mr. Holmes in Report of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, pp. 153-158. 56 Mr. Rice in Report of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, pp. 257-258.

53

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

42

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

laborer are much more encouraging and support the hope that the islands can be rapidly and well developed without the importation of foreignlabor. Writing in 1903, Mr.Taft says that as conditionssettle the Filipinocan be made a good laborer,not so good as the Americanor Chinese,but one with whom it will be possible to carry on great constructiveworks.57 He cites statementsfromH. Krusi, vice-presidentof the Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific Company, who was successfully using native labor and who thought that though the Chinesewould expedite the development of the islands, yet in the end they would do injury.58 It is worthy of notice that while ChiefEngineerHolmesof the Philippine Commissionwas one of the most severe in his condemnation of the Filipino as a laborer,his successor,MajorL. W. V. Kennon, has looked favorablyupon their work. The Report of the PhilippineCommission in 1906 is very optimistic of the future of native labor and sees the chief difficulty in securing competent supervision. The work of the Filipino on the railroads,in the shipyards, on the street railway lines, on the farms and in mining is upheld and praised.59 "The Filipino expends energy enough to make the country a garden but it is not properlydirected."60 So much then for the respectivemerits of the native and the Chinese labor. The contentionsover the questionare so diverse as to preclude any dogmaticconclusions,but it is at least evident that the case against the Filipino has not been adequately and sufficientlyproven. Hence he should be given a liberal opportuntiy to demonstrate whatever ability he may possess. The attitude of the natives toward the Chinese ought to be consideredin the adoption or rejectionof a policy of exclusion. With few exceptionsthe Philippineinhabitantsare opposedto the free admission of the Chinese. As early as 1903 Mr. Taft wrote that it would be a "great politicalmistake"to admit freelythe Chineselaborers.6' Industrially the natives hate the Chinese.62 Dr. Victor S. Clarkreportsthat

57

Report of the Philippine Commission (1903), vol. i, pp. 54, 55. Report of the Philippine Commission (1906), vol. ii, p. 69; vol. iii, p. 776.

58 Ibid.

59

60 Ibid., vol. ii, p. 496. 61 Ibid. (1903), vol. i, pp. 54, 55.

62

The Philippine Islands (Atkinson), p. 261.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

43

"no Filipinowas found, whetheremployeror employee,who wishedthe present exclusion policy amended."63 Again he says, "All Filipino

employers and employees interviewed

..

.

were opposed to

the admissionof the Chineseon any terms; and "a plebiscite of all personsin the Philippineswould appear almost unanimousin favor of the present exclusion laws."64 The native opposition, indeed, is not questioned. To a certainextent, therefore,the Filipinois imbuedwith the idea of developingthe islands himself and for himself and unquestionably it would be inviting political oppositionfor the United States to throw open the countryto exploitationby any other race of laborers. In additionto the oppositionof the Filipinopeoplethemselvesto any changein the exclusionpolicy, the Americanmerchantsin generaland many in particularare avowedly opposed to the free admissionof the Chinese. It must be admitted, however, that there is a diversity of opinionamongAmericanemployers,especiallyas between military and civil employers. The sugar planters unanimouslyoppose any change. The demandfor the admissionof the Chineseis analyzed as being confined to two principal sources and as being localized in these. The sources are the Americanemployersjust mentionedand the European employers, the latter, excepting those of the mercantile class, being practically unanimous against exclusion.65 The shipbuilders are for the admissionof the Chinese. mentionedas beingthe most clamorous to Washingsent a representative of Commerce The AmericanChamber ton in 1903to urge the modificationor repealof the exclusionlaws, but to no avail. Since that time the agitation in this body has died down to a great extent.66 The chamber of commerce also included the Spanish, English, and German interests. The principalpoints urged in favor of the desired admission of Chinese labor are: (1) Labor is scarce; (2) the Chineseare necessary for the business development of the islands in orderthrough skilled labor to preservecertain industries already establishedand to enable others to be undertakensuccessfully against Chinese competition on the mainland, and through unskilled labor to build roads and public improvementsand work in mines and

Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor no. 58, May, 1905, p. 861. Ibid., pp. 896, 897. 65 Ibid., pp. 862, 863. 08 Ibid., p. 863.

13 64

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

44

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

agriculture especiallyin the thinly settled and remotedistricts;67(3) and finally the Chineseare necessaryin orderto make the Filipino work.68 Admittedly the manufactureof hemp and shipbuilding have suffered somewhatbecauseof competitionwith China. This has been offsetto a large extent, however, by the protective tariff of 1905 which is now in force. The necessity for unskilled labor is not made plain. And as for the presenceof the Chinesebeing an incentive for the native to labor the burden of the testimony seems to show that the pressureof such competition forces the Filipino downward. Accordingto an investigation made as early as 1593 the Chinese competition in the islands caused a cessation of native industry.69 Testimony to the same effect has been previouslycited in this discussionand was based on experience since American occupation. Besides the extreme scarcity of native labor is a difficultywhich has apparentlybeen overcomein large measure, for in 1906 Mr. Dean C. Worcester,secretaryof the interiorfor the Philippine Commission,states in his annual report that the supply of Filipinolabor is abundantand satisfactoryat very low prices.70 Other testimony is plenty to show that employerscan get all the native labor they desire and that they are constantly replacingthe Chinesewith natives as rapidlyas the latter becomesufficientlyskilled. are objectionsto to these more importantconsiderations Subordinate exclusion based on the difficulty of executing the policy due to the proximity of Chinaand the desire of Chinesestowawaysto land in the islands.1' The idea is also urged that it is better for the Malay to let the coolie do the lower grades of work and the native himself aspireto higher things.72 The debt to the Chinesefor their having taught the natives long ago many of the things they now know about industry and ;73 the contention that only by the admission of the Chinese commerce can the United States ever be recompensedfor what the islands have ;74 that the influx of the Chinese would really be a cost this country

67 68

Report of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, pp. 21, 22. Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 863. 69 Census of the Philippine Islands, vol. i, p. 485. 70 Report of Philippine Commission (1906), vol. ii, p. 69. 71 Report of Philippine Commission (1902), pt. ii, p. 840. 72 Philippine Life in Town and Country, p. 95. 73 New Era in the Philippines, p. 82.

74

Ibid., p. 87.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

45

great source of revenue;75 that the limited introduction of Chinese instructors in agriculture would better the present crude methods;76 and that the strict enforcementof the exclusionlaws and the deportation of unregisteredChineseinvite opposition from powerfulinfluences in the businesscommunity;77 these reasonsare all cited and involved in the efforts to modify or abolish the exclusion policies of the American and native governmentsin the Philippine Islands. And last but not least are the superficialobservationsof Americanand Europeantravelers in the islands, most of whom judge from what the Chinamanhas accomplished in the Straits settlements, Siam and other Asiatic tropics and come too hastily perhapsto the conclusionthat the presenceofthe Chineseis imperativein the Philippineswheresuch progresshas not yet taken place.78 The conclusionsof Dr. Victor S. Clark,as expressed in his report on Labor Conditionsin the Philippine Islands, are based on a personalstudy of the situationin 1905 and favor continuedexclusion, relying for the maintenance and extension of industry on the presentmechanicand operativepopulationand the additionswhich are constantly being made to it from the ranks of the natives. Another recent student in the Philippineswrites that "the businesspeople most friendly to the Filipinos believe that the Chinese would hasten the economic development of the islands wonderfully,but admit that the Chinese are not necessary." A unique suggestion has been made to supply temporary demands for labor by five year importations of Chineseat good wages, with Filipino apprenticesfor every Chinese,the latter to be taxed $50 per head on admission,and the employerto be put under bond to return the Chineseto China at the end of the five years, by which time "there will be enough skilled Filipinos."79 One is thereforejustified in view of all the evidence in concludingthat the admissionof the Chinese,either freely or undermoderaterestrictions, would hasten the economicdevelopmentof the islands. An elementof growingimportancein the consideration of the Chinese problemin the Philippinesis that of labor organizations. The latter

7-An English Woman in the Philippines, p. 176.

76 77 78 79

The Philippine Islands, p. 177. Report of Philippine Commission (1903), vol. iii, p. 307. Cf. H. C. Stuntz' The Philippines and the Far East, pp. 265-283. Report of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, pp. 9, 10.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

46

THE

AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

have had a remarkablegrowth since American occupation and are particularlyalert on the question of the admissionof the Chinese. In additionto the argumentsalready advancedfor exclusionthey cite the following: (1) that it takes the Chineselaborerbut one to two years to become a merchant,thus inviting a continualinflux of low class labor and preventinga rise in the general conditionsof labor; (2) that labor organizationis spreadingamong the natives with good results and will do muchtoward makingthe Filipinoan efficientworkman;(3) and that the admission of the Chinese will forever prevent the opening of the United States markets freely to the Filipinos,for such a policy would mean Americancompetition with Chineselabor.80 The most important of these observationsis the last. One of the chief hopes of the Filipino since Americanoccupationhas been that of free trade with the United States. It has been continuallyadvancedas the most effective and immediate method of stimulating development in the islands. Certainit is that in the presenttemper of the American peopleand their attitude towardcompetitionwith Chineseand Japanese labor,no thought of freetrade with the Philippinescould be entertained if the exclusion policy should be abated. The sentiment prevails in Philippine mercantile circles that the admission of the Chinesewould constitute a permanentbarrierto even favorable trade relations, and that of the two measures the latter would be most beneficialin the development of the islands.8' Says one business man in the islands, "their (Chinese) admission would destroy our chance of tariff concessions from the United States-which is very much more important for the country."82 As far as governmentalrelations are concernedit is allegedthat without exclusionChineseblood wouldsoon predominate and Americawould soon have a Chinese dependency"from which we might well seek deliverance."83 To what extent modificationsof the present system of governmentwould be necessaryis nowhereoutlined. Owingto the submissive and peaceful traits of the Chinesethey probably wouldnot be great or radical. But the policy wouldchangefundamentally, for the present policy is, ostensibly at least, to make a selfReport of the Philippine Commission (1902), part i, pp. 21-23. Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 863. 82 Ibid., p. 865. 8' The Philippine Islands, p. 260.

80 81

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

PROBLEM

OF THE

CHINESE

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

47

governing democracy out of the Filipino people. This end could not well be furtheredby the influx of a large Chinesecoolie population.84 One phase of the problemyet remainsto be considered-that of the Chinese mestizo or halfbreed. As to the character of the mestizo opinionsdifferwidely. The willingnessof the Chinamanto intermarry whereverhe goes has been notorious, and in the Philippinesit is very marked. One writer remarksthat Chinese infusion turns out sharp, intelligent, ambitious, but untrustworthyindividuals.85 Another says the Chinese mestizos are "the most progressive industrial force."86 the halfbreeds In the testimony beforethe First PhilippineCommission are alleged to be "troublesome. "'87 Mr. Atkinson claims that the children of Chinese husbands and native women are "energetic and superiorto the pure Filipino in ability and force of character;" also that the mestizosare reputedto be the " keenest and shrewdest" of the population.88 Mr. Brown states that the mestizo is virile, industrious, peacefuland law abiding, and that the Filipino race needsthe stimulus of new blood.89 Muchother evidence pro and con could be cited, but enough has been given to enable a conclusionthat the interminglingof the races, while not attended with the bad results which are so often apparentin the associationof peoples more differentin race, color and standards of life, is sufficiently undesirableto make its prevention a matter of some concernand effort. True it is that the characterswho have given the United States the most troublein the matters of government are not the native Filipinoswho are anxious to see their country independent,but the Chinesemestizos such as Aguinaldo,Gomez,and others, able and active, but withal selfseekers. In summingup the results of this investigation,one may rightly conclude that as far as racial,politicaland national interests are concerned the exclusion of the Chinesehas been and continuesto be a justifiable policy. From these sources must come the main support as yet for exclusion measures. From an economic point of view the policy of

Bulletin of Bureau of Labor, no. 58, May, 1905, p. 872. The Philippine Islands, p. 260. 88 Handbook of the Philippines, p. 43. 87 Report of Philippine Commission (1900), pp. 19, 187-190. 18 The Philippine Islands, pp. 261-263. I"New Era in the Philippines, pp. 82-85.

84

8I

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

48

THE AMERICAN

POLITICAL

SCIENCE

REVIEW

exclusion is a questionableone, especiallyinasmuchas free trade with the United States has not been secured and is very uncertain, if not unlikely. The balanceof the argumentappearson the surfaceto be in favor of the admission of the Chinaman, at least under moderate restrictions. But even this conclusionmay be taking snap judgment on the Filipinos. Their economic development since American occupation has been steady and acceleratingin pace, even though still comparatively slow. However, it has not been shown that the Filipino cannot develop the islands, nor can this now be shown. The native in the past ten years has had to learn the dignity of labor, the objects of labor. He has had to acquire wants in order to stimulate to earning activity. He has had, moreover, to shoulder part of the burden of planning for his country's future. Well indeed, if by far the greater numberof witnessesmay be credited,has the native met the demands laid upon him. Today the islands are looking forwardto a more prosperous future and to at least closer trade relations with the United States. To admit the Chinese now is to invite a disturbing social, political and economic factor into the life of the islands. Until the United States is herselfwilling to open her doors freely to the laborers of Chinaand risk the encounterbetween Chineseand Americanstandards of life, it does not behoove this nation to invite a similarconflict betweenthe Chineseand the Filipinos,the latter not having reachedour standards, but hoping to do so and engaged in an earnest effort to accomplish this end. The present number of the Chinese is not a menace to peace and industry in the archipelago. They will soon be absorbedin the native population. The danger lies in the coolie class who in the struggleto advance themselveshinderthe upwardcourseof the Filipino. To best conserveand advance the politicaland economic interests of the future Philippinenation, therefore,the continuanceof the present policy of exclusionseems advisable.

This content downloaded from 180.191.105.224 on Sat, 27 Apr 2013 21:01:22 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Mafia Style Domination in The PhilippinesDocumento48 pagineMafia Style Domination in The Philippinesprofmarkdecena100% (1)

- An Interpretation of 1953 Presidential ElectionDocumento12 pagineAn Interpretation of 1953 Presidential ElectionprofmarkdecenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Global AuctionDocumento209 pagineGlobal AuctionprofmarkdecenaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Commercial Awakening of The Moro and PaganDocumento11 pagineThe Commercial Awakening of The Moro and PaganprofmarkdecenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Economics A Citizen's Guide To The EconomyDocumento379 pagineBasic Economics A Citizen's Guide To The Economyprofmarkdecena95% (20)

- Political BossesDocumento12 paginePolitical BossesprofmarkdecenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Slide HR Training and DevelopmentDocumento31 pagineSlide HR Training and DevelopmentSyurga FathonahNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainability Management Plan: Movenpick Hotel Ibn Battuta Gate DubaiDocumento39 pagineSustainability Management Plan: Movenpick Hotel Ibn Battuta Gate DubaiEka Descartez0% (1)

- Director Sales Operations in CT New York City Resume Barry HornDocumento2 pagineDirector Sales Operations in CT New York City Resume Barry HornBarryHornNessuna valutazione finora

- General Counsel Legal Strategy in Detroit MI Resume Stephen SerrainoDocumento3 pagineGeneral Counsel Legal Strategy in Detroit MI Resume Stephen SerrainoStephenSerrainoNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2 PM Harold KerznerDocumento46 pagineUnit 2 PM Harold Kerznerrehanrafiq59Nessuna valutazione finora

- KM Slides Ch04Documento23 pagineKM Slides Ch04anon_239840436Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Harassment at InfosysDocumento10 pagineSexual Harassment at InfosysswastikmalusareNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar Exam Labor LawDocumento15 pagineBar Exam Labor LawNolram LeuqarNessuna valutazione finora

- Zimmerer 1-3sDocumento18 pagineZimmerer 1-3sTian ChengNessuna valutazione finora

- Appointment OrderDocumento4 pagineAppointment OrderSuresh BabuNessuna valutazione finora

- EssayDocumento2 pagineEssaymoazamzahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnostic Study Report of Grape Cluster Nasik MaharashtraDocumento24 pagineDiagnostic Study Report of Grape Cluster Nasik MaharashtraanjanianandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Layoff Case Analysis FinalDocumento15 pagineThe Layoff Case Analysis FinalAnupam Chaplot100% (1)

- Guide To Employment Law in Hong KongDocumento48 pagineGuide To Employment Law in Hong KongAnjali PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study: Nordstrom's Customer Service Culture Serves As A Control MechanismDocumento5 pagineCase Study: Nordstrom's Customer Service Culture Serves As A Control MechanismAngie RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical SpecificationDocumento54 pagineTechnical SpecificationPaula SisonNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal and Group EthicsDocumento15 paginePersonal and Group EthicsMuthuvarshini SNessuna valutazione finora

- Coporate Governance EssayDocumento6 pagineCoporate Governance EssayDea ElmasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 06 24 Code of Conduct For Members Headed OscrDocumento25 pagine2014 06 24 Code of Conduct For Members Headed Oscrabdirisak SalebanNessuna valutazione finora

- Wpe & ZTPDocumento2 pagineWpe & ZTPJay JoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Audit of Kenton County Airport BoardDocumento70 pagineAudit of Kenton County Airport BoardLINKnkyNessuna valutazione finora

- Monsters, Inc.: Toxic Leadership and EngagementDocumento13 pagineMonsters, Inc.: Toxic Leadership and EngagementRudiSalamNessuna valutazione finora

- A' Grade NAAC Accredited UniversityDocumento6 pagineA' Grade NAAC Accredited Universitybirendra bistaNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 Business Ideas For 2020 MillionairesDocumento51 pagine14 Business Ideas For 2020 MillionairesAbu UmarNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Resources Department of Bank of Uganda PDFDocumento2 pagineHuman Resources Department of Bank of Uganda PDFhariNessuna valutazione finora

- Employee Capacity Calculator 2021Documento7 pagineEmployee Capacity Calculator 2021Nirmal GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- A54 701 Administrative Clerk FSN 6Documento5 pagineA54 701 Administrative Clerk FSN 6sekaboNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Background QuestionnaireDocumento3 pagineBusiness Background QuestionnaireWendyMayVillapaNessuna valutazione finora

- ePACIFIC GLOBAL CONTACT CENTER v. CABANSAYDocumento2 pagineePACIFIC GLOBAL CONTACT CENTER v. CABANSAYCamille DuterteNessuna valutazione finora

- Job Satisfaction QuestionnaireDocumento3 pagineJob Satisfaction QuestionnaireSaba RajpootNessuna valutazione finora