Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

41 Full

Caricato da

Gina Beatrice PanăDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

41 Full

Caricato da

Gina Beatrice PanăCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Adult Education Quarterly

http://aeq.sagepub.com/ Humanism and Individualism: Maslow and his Critics

Elaine M. Pearson and Ronald L. Podeschi Adult Education Quarterly 1999 50: 41 DOI: 10.1177/07417139922086902 The online version of this article can be found at: http://aeq.sagepub.com/content/50/1/41

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Association for Adult and Continuing Education

Additional services and information for Adult Education Quarterly can be found at: Email Alerts: http://aeq.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://aeq.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Nov 1, 1999 What is This?

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM ADULTAND EDUCATION INDIVIDUALISM QUARTERLY / November 1999

HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM: MASLOW AND HIS CRITICS

ELAINE M. PEARSON

University of South Dakota

RONALD L. PODESCHI

University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

This analysis explores the philosophical issue of the individual-society relationship through a focus on Abraham Maslows humanistic psychology and its significant influence on adult education in the United States. Analyzing the points of contention between the key assumptions of Maslow and recent critics, particularly Marxist and postmodernist scholars, the study concludes with perspectives that do not abandon humanistic possibilities while pinpointing its problems.

At the turn of the new century, a key issue that underlies questions concerning purposes and practices in education is that of the individual-society relationship. Whatever our view is about the primary aim of adult education, our position is directly related to our assumptions about individual freedom, societal forces, and responsibility. And questions of practice as well as purpose are sorted out further by premises (even when hidden) concerning freedom and control, identity and socialization, commitment and power, and possibilities and constraints. The individual-society issue is far from new, roaming Western thought through the centuries and permeating educational classics from Plato to Rousseau to Dewey. But in any particular era, or in any particular nation, consensus or conflict about the issue plays out in those specific contexts of history and culture. Indeed, the issue of self and others plays out ultimately in the day-to-day lives of people and their institutions. Although our analysis will be skewed toward the United States, there are potential implications for adult education in other countries, especially those influenced by U.S. mainstream culture and its core value of individualism. During the 20th century, U.S. education at times had to face the individualsociety issue head-on in political conflict (e.g., ethnic pluralism vs. assimilation),

ELAINE M. PEARSON is the director of disability services at the University of South Dakota. RONALD L. PODESCHI is professor emeritus of educational policy and community studies at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY, Vol. 50 No. 1, November 1999 41-55 1999 American Association for Adult and Continuing Education

41

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

42

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

while at other times, the philosophical issue became muted under professional consensus and unexamined premises (e.g., during drives for technical professionalization). Whatever the historical context, underlying assumptions concerning the self-society relationship inevitably affect the perceived purposes and patterns of practice in adult education, whether labeled liberal development of the mind, progressive development of democratic citizens, behavioristic social engineering, humanistic faith in personal growth, or radical societal reconstruction (Elias & Merriam, 1995). Since midcentury in the United States, humanistic adult educationas an extension of the learner-centered strand of earlier progressive adult education, and significantly influenced by midcentury humanistic psychologypromoted its premises about personal autonomy and social progress. In recent decades, criticism of certain elements of humanism has mounted in scholarly discourse, reflecting current movements such as critical theory, feminist theory, Afrocentrism, and postmodernism. These new theoretical influences in the social sciences and education have created a deeper level of conflict among competing frameworks of theory and practice, eroding long-held assumptions in U.S. adult education. One such assumption is at the heart of humanism, the idea of an intrinsic selfa belief, say critics, that is not only naive but also harmful. However, criticism of humanistic individualism is not just at a theoretical level. A potpourri of critics in everyday politics and education range from religious conservatives attacking secular humanism to unempowered groups questioning the power of the mainstream individualism that permeates all aspects of American life. In the midst of this ideological spectrum are also those who are concerned about a contemporary culture of individualism, wherein technical methods overshadow ethical ends, and cost-benefit management of relationships overshadows commitment to others. In Habits of the HeartIndividualism and Commitment in American Life, Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, and Tipton (1985) analyze contemporary U.S. White, middle-class culture as exemplified by prototypes of the bureaucratic manager and the therapist, and reflecting a synthesis of economic individualism and psychological individualism. In such a culture, a major dilemma results for Americans: How can citizens create alternative ways for placing individual freedom within a moral context of community when they are immersed in the culture and language of this contemporary individualism (Podeschi & Pearson, 1989)? Now, we are in an ever-expanding computer universe, one in which questions about privacy, privatization, the public good, family and community, the civil society, and the role of government are pushed into higher speeds and onto such untraveled roads as the Internet, economic and cultural globalization, and genetic engineering. In spite of this new era, the individual-society issue carries an old dilemma, one that William James posed at the end of the 19th century: How are we to enhance creative individuality in the face of the forces of bigness, whether in the form of bureaucracies, systems of thought, or social movements (Cotkin, 1990)?

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

43

Connection of such a question to adult education is particularly acute in the United States because of its increasingly global influence from political, economic, and technological forces. It is an opportune time for adult educators to assess critically past humanistic assumptions while preserving humanistic underpinnings that may have value for an unknown future. Our exploration in this article will focus on Abraham Maslow, his key assumptions in dealing with the self-society relationship, and the major points of contention with his critics. As Elias and Merriam (1995) contend, humanistic adult education with its enormous impact of andragogy and self-directed learning are rooted in the work of Maslow and Carl Rogers. There is no doubt that Maslow had an important impact on theoretical assumptions during the era of academic growth in adult education, he being one of the most cited authors in an analysis of adult education research from 1968 to 1977 (Boshier & Pickard, 1979). Since then, several Marxist critics in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology specifically target Maslow, whereas postmodernists build their own rejection of humanistic assumptions. Within education, scholars such as Bowers (1987) portray humanists such as Rogers as uncomplicated romantics, and critics of mainstream adult education (e.g., Muller, 1992; Pratt, 1993) take apart assumptions about individual autonomy and their roots in humanistic psychology espoused by andragogys leader, Malcolm Knowles. Whereas categories of philosophy of education such as humanistic are helpful in citing major differences in assumptions, there is a potential for overgeneralizing about any category and, as a result, for neglecting differences among those so labeled. We choose to focus on Maslow because we find that in contrast to humanists such as Rogers and Knowles, Maslow assumes that individual capacity for freedom is significantly affected by ones environment (Podeschi & Pearson, 1986). For Maslow, good social conditions are needed to facilitate fulfillment of intrinsic human nature, promoting both the universality and uniqueness of the individual. With responsibility for her or his own growth, the individual in turn will further fertilize the societal soil. Even so, in spite of differences with other humanists, Maslows psychology and education are characterized by core elements that have remained at the heart of humanism through varied historical permutations. We shall now focus on these core humanistic assumptions within the context of U.S. mainstream culture, then review certain criticisms of humanism, and conclude by exploring our own framework and perspectives concerning the persistent individual-society issue and adult education.

MASLOWS HUMANISTIC ASSUMPTIONS AND U.S. CULTURE

Lying at the heart of Maslows work are assumptions of human-centeredness, a sense of personal autonomy, the idea of human dignity, the principle of virtuous

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

44

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

action, and a sense of personal responsibility. Said another way, four intertwining concepts form the set of premises underlying his humanistic psychology: the idea of a self, capable of growth, responsible for what one becomes, and capable of influencing social progress. There is an inner core of the self-determining individual in which human freedom for Maslow is a combination of uncovering ones real self and deciding what one will become. This capacity for self-knowledge and willed self-renewal leads to growth (the self-actualizing process), moving the self from one state of consciousness to a more advanced state (e.g., basic needs of safety and belongingness to meta needs of wholeness and justice). For Maslow, knowledge of oneself is not only a path to better individual value choices, but self-actualization also leads to knowledge of universal human nature, for example, awareness of the synthesis of altruism and self-interest (Pearson, 1994; Podeschi, 1983). Maslows key assumptions (and humanistic adult education) need to be seen within the cultural context of U.S. mainstream culture, their parallel with this culture as well as their divergence. As Stewart (1979) contends,

The concept of the individual self is an integral assumption of American culture so deeply ingrained that Americans ordinarily do not question it. They naturally assume each person has his own separate identity which should be recognized and stressed. (p. 68)

In contrast to other cultures, especially non-Western, children in the United States are exposed to a mainstream socialization that promotes decisions and opinions that revolve around self. This mainstream culture, however, has a paradoxical character, one that reflects tension between self and others. Whereas there is a core U.S. value of individualism that is girded by beliefs in self-reliance and self-motivation, this core value also is a collective individualism involving association with others and belonging to organizations. Self-identity is tied not only to individual achievement but to group activity as well, the self being subjected often to social pressures. The need for acceptance by others, especially when ones individual achievements can be enhanced by group cooperation, may lead to conformity rather than genuine individual independence. And self-reliance may lead to an insecurity wherein the self is anxious about being replaced by others as he or she sees others as replaceable in a competitive society. Group associations may be seen by the individual as replaceable as well, depending on the perceived needs as a self (Podeschi, 1986; Stewart, 1979). Maslow is not naive about this mainstream pressure on the individual. His philosophy of the individual-society relationship reflects awareness on his part of this cultural tension between self and others, his self-actualizing individual resisting social conformity. Maslow (1962) also recognizes and faces existential tensions between the self and others, those that are part of the human condition. For example,

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

45

in his view of self-actualization as both self-concerned and concerned for others, he writes,

there must be choice, conflict and the possibility of regret. . . . Being true to yourself may at times intrinsically and necessarily be in conflict with being true to others. A choice can only rarely be completely satisfactory. (pp. 120-121)

Although there are such existential dimensions in Maslow on the individual level, his assumptions about social change portray an American optimism similar to some of the earlier progressives as well as more recent humanists. In attempting to erase dichotomy between the self and the social environmentreflecting Maslows biographical synthesis of Freudianism and behaviorism (Hoffman, 1999)he carries a faith in the simultaneous improvement of individuals and their society. This faith reflects a U.S. belief in progress, one fueled by other mainstream values such as newness and change, with education as a road to renewal of society as well as the self. Such humanistic assumptions are what receive strong reactions from critics. We now turn to examples of such criticism, then conclude with our own perspectives about the possibilities of human freedom.

MASLOW AND MARXIST CRITICS

As humanistic psychology and education grew in prominence, criticism rooted in Marxist social and economic analysis took shape, much of it aimed directly at Maslow. The overall point of contention for such critics in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology is that there is an excessive individualism in humanistic psychology and education that is essentially elitist. There are weaker and stronger versions of this criticism. Some argue that Maslow is unconsciously naive about elitist elements in his theories. As one critic poses, What real individuals, living in what real societies, working at what real jobs, and earning what real income have any chance at all of becoming self-actualizers? (Lethbridge, 1986, p. 90). For some critics, Maslows elite self-actualizers are seen as the psychological embodiment of the social elites who are the decision makers of his society, and they assert that he remains unaware of the value-laden nature of his theory. Such critics contend that the nature of excessive individualism contained in the doctrine of self-actualization, with its emphasis on self and responsibility, serves to mask the larger questions surrounding societal structure: A theory that predisposes one to focus more on individual freedom and development rather than the larger social reality, works in favor of that reality (Buss, 1979, p. 46). Meanwhile, other critics assign Maslow a much more malevolent role, seeing his psychology as a new and seductive Social Darwinism that is used to justify a capitalistic system with its privileges and practices for its powerful elite (Shaw & Colimore, 1988, p. 56 ). The resulting problem these critics see is,

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

46

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

Those who fail to reach the heights described by Maslow may feel that they are personally to blame for their discontent. . . . The individualization of success and failure can also result in blaming those who suffer from social injustice for the hardships they face. (Shaw & Colimore, 1988, p. 60)

Whether of the weaker or stronger variety, these critics base their arguments on a set of assumptions opposed to the dominant humanistic view of the nature of the individual. They particularly reject any notion of an autonomous self, instead emphasizing the determination of macro socioeconomic forces on the shaping of any individual. In this set of assumptions, human nature is human only by virtue of the society; it is historically developed and not in any sense inherent in any particular individual. This basic Marxist premise leads to the aim of achieving economic, political, and social equality through reshaping society and, in turn, reshaping human nature. Having nothing but scorn for Maslows goals of achieving social improvement gradually, these critics see such piecemeal progress as part of a soft progressive frame of mind. Such optimism that individuals can surmount the social, political, and economic realities of their lives and that this can improve society is, in the weakest reading, naive and, in the strongest reading, a device for maintaining those inequitable realities. Certainly, these critics oppose Maslow and humanistic adult education on the basic assumptions of self, growth, responsibility, and progress. In response to his Marxist critics in the 1960s, Maslow (1971) goes right to the core assumptions. He rejects their either/or characterizations, and although not arguing against the idea that human nature (the self) is a social process of becoming, he does argue that this is only one part of the story: Culture is only a necessary cause of human nature, not a sufficient cause. But so also is our biology only a necessary . . . and not a sufficient cause (p. 156). Maslow locates responsibility in both the individual and in social conditions. The inner core shows itself as natural inclinations, propensities, or what he calls an inner bent, and the raw material of this inner core begins rapidly growing into a self as it meets the world and begins to have transaction with it. These potentialities, which have a life history, are actualized or stifled primarily, but not altogether, by culture, family, environment, and learning (Maslow, 1962). In reacting to the Marxian stance against incremental progress, Maslow views human nature as far too complex and varied to allow for such perfection and argues that social contradictions reflect an actual tension in human nature. For him, both progress and regress are possible, and the Marxists err in holding out for a deterministic perfection: Giving up hope for progress almost certainly means regression and worsening, he writes, So in [my] hope and theory, progress is itself a dynamic determinant (Lowry, 1979, pp. 383-384). Although Maslows journals do show that he took seriously the Marxist criticisms leveled at him, he argues that it is Marxist pessimism that is mistaken. He

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

47

rejects total pessimism as well as total optimism: This all-optimism all-pessimism thing has to be killed off (Lowry, 1979, p. 1237). Unfortunately, Maslow was dead by the time humanism became confronted by postmodernism, which offers a different kind of challenge. We shall next analyze the brunt of this criticism and then turn to exploring our own framework of humanistic freedom within the contexts of the critics and from perspective three decades after Maslows death.

POSTMODERN CRITICISM OF HUMANISM

Postmodern criticisms, varied enough to be called postmodernisms, are devoted to dissolving the foundational assumptions underlying all 20th-century thought flowing from The Enlightenment. They target most specifically the central assumption of an essential inner human nature. Whereas the humanistic individual is at least potentially capable of making himself or herself a better person, of fulfilling the highest possibilities of an intrinsic inner nature, of choosing the highest human values, a postmodernist such as Michel Foucault denies that there can be any foundational, universal, or normative assumptions about human nature and rejects any notion of a self or of self-actualization. Our analysis will spring from the perspectives of Foucault, because he has had the most singular influence on postmodernist scholarship in the United States, including the field of education. But we do not imply that he speaks for all of postmodern thought. Whereas the issue of power is at the heart of Foucaults thought and influence, some interpreters of postmodernism and adult education (e.g., Edwards & Usher, 1997) have only a minor focus on power while describing the major condition of contemporary society as one of increasing complexity, uncertainty, globalization, playfulness, image, and lifestyle. Opposing what he calls the California cult of the self, Foucault views the humanistic individual as only a consequence of practices of power, not as Maslows autonomous individual with an intrinsic nature. He does not view power, however, as do the Marxists, as top-down macro forces. For him, every individual is at once both an object and a subject of power, and these power relationships are capillary in nature and are inscribed at the heart of every human relationship (Rabinow & Dreyfus, 1983). For postmodernists such as Foucault, belief in an intrinsic human nature only reflects how individuals have been enculturated into thinking of themselves as certain kinds of persons. In reality, then, beliefs about masculinity or femininityembedded in a universal holistic concept of an intrinsic self that needs to be discoveredreflect power relationships. Processes such as psychoanalysis, meditation, and confession, through which such discovery is to take place, are actually only practices of power that hide from us the arbitrary nature of these constructed selves.

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

48

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

Foucault describes how in our current regime of truth that defines what is possible to say or think, people have gradually come to be defined, and to define themselves, by certain classes of behavior. These subjectivizing processes reflect a form of

power [that] applies itself to immediate everyday life, which categorizes the individual, marks him by his own individuality, attaches him to his own [intrinsic] identity, [and] imposes a law of truth on him which he must recognize and which others have to recognize in him. (Rabinow & Dreyfus, 1983, p. 212)

In Foucaults view, we are each tied to our own identity by a conscience and by self-knowledge, all constructed for us by practices of power. Such practices come together, for example, through the concept of the normal. Categorized hierarchically, differentiated around a norm, we are punished by sanction or exclusion when we deviate from the norm. Judgments of good and bad, once ascribed to certain behaviors, play out differently in the current era of bureaucratic classifications. Now these judgments are ascribed to individual selves because of their behavior (Foucault, 1979). In much of postmodernism, then, the notion of Maslows self is flatly rejected. Change occurs, but notions of growth and progress are rendered meaningless. Responsibility in its humanistic sense drops from the vocabulary, being one of the practices of power that creates individuals and humanistic truthdangerous illusions. From Maslows perspective, such a confining analysis around power relationships would be an excessively limited view of human reality, especially in its denial of any individual freedom to effect meaningful change. Our own emerging position about the possibilities of human freedom can be made more clear by continuing with Foucault and then returning to Maslow. In the postmodernism of Foucault, human agency as truth is an illusion because in the regime of truth that creates the modern era, all we have are endless interpretations rather than truth(s). Freedom is another of those illusions. There cannot be freedom from domination, because in every interaction, we are subjects and objects of power, and any freedom from practices of power is an illusion as the idea of freedom itself becomes one of the practices of power. Education is just one of those areas, and anyone who has experienced an educational system may respond to Foucaults rich descriptions of daily life in schools with a deep click of recognition. Similarly, women and minority individuals find that postmodern analyses of the politics of everyday existence resonate with their own experiences. Understanding how many of our assumptions about ourselves and our world have come down to us through the tacit knowledge that very few of us question cannot only open our eyes to that social construction, but such understanding can free us for the important follow-up stage that Taylor (1986) calls self-making. Many scholars have noted the pessimism of postmodern voices on freedom and truth. Yet, one comes away from reading many of the postmodern writers with a

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

49

sense that although explicitly denying the possibilities, nevertheless they seem to be holding implicitly to the ideals of freedom and truth and urging their contemporaries to action in the service of truth and freedom (Fraser, 1985; Pearson, 1994; Taylor, 1986). There is another problem arising from the view of historys cumulative imprint on human nature and the consequential belief that our selves are totally constructed by practices of power. And that is the question of how postmodern voices, dissident as they are in terms of Enlightenment assumptions, were able to emerge. If our selves are totally constructed, postmodern voices are impossible in their own terms. Our explanation is that there must be something in addition to power relationships and practices, because individuals who think against the grain of, or at oblique angles to, these totalizing practices do indeed exist. We believe that these voices rightly call our attention to how much of our self-knowledge is socially constructed and how our beliefs in an essential human nature have been an integral part of disciplinary practices of power that have created the conditions within which we live. However, we also believe that it is not only possible to retain the assumption that there is something in humans that impels us toward growth as individuals and impels us to attempt to improve our human society but that it is impossible to understand the reasons for postmodern criticisms in the absence of such a human characteristic.

INDIVIDUALISM, INDIVIDUALITY, POWER, AND FREEDOM

Our position is that the similarities as well as the differences between Maslow, his critics, and other humanists can be sorted out more clearly if a neglected distinction between individualism and individuality is put into focus. When we make such a distinction, the prime target of the critics of Maslow may be seen as individualism, whereas a prime developmental goal for Maslow is individuality, even though he confused it frequently with ingredients of individualism (Pearson, 1994). Grant (1986) explains that there are three defining characteristics of individualism and that contrary to conventional wisdom, it is not the opposite of conformity. One definition is the metaphysical position that the individual may exist apart from any social arrangement, that is, independent of society. Another defining characteristic is the attitude that the individual person and his or her rights and needs take precedence over all collectives, spanning all moral and political decision making. And a third is the attempt to study society by exploring the actions and intentions of individuals rather than analyzing societal institutions and macro forces. We see Maslow as neglecting the distinction between individualism and individuality because his work focuses on individual acts and intentions; and although he gives weight to cultural forces, his lenses are primarily on individual efforts to resist these forces. But Maslows conflation of individualism and individuality may be seen most clearly when individualism is defined in the metaphysical position

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

50

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

that the individual exists apart from any social arrangement. His insistence on an intrinsic inner nature certainly takes him into this metaphysical territory. Individuality, on the other hand, is a term defining individuals both in terms of their uniquenesses and in their particular embedment within the social matrix. Individuality, then, is the opposite of conformity, whereas individualism is the opposite of socialism (Arieli, 1964; Grant, 1986). Many of us use the terms individualism and individuality interchangeably, without understanding the distinctions between the concepts, and consequently are caught in a philosophical double bind in which we cycle needlessly between individual and societal needs. It occurs inevitably if we see ourselves as cycling endlessly somewhere on a single continuum between individual needs and societal order. Although Maslow does not make such a distinction clear, he does implicitly use language that makes an unacknowledged distinction when he stresses both the uniqueness of individuals and their human commonalities. And he leans toward using such a distinction when asserting that autonomy theory can never be a satisfactory basis of social psychology, as well as when he advocates the concept of synergy as a fusion of self and world, a cornerstone of Maslows work. An underlying assumption of endless and necessary tension between the individual and the society leads, among other things, to a disparagement of this concept of synergy. From the perspective of a single continuum, the individual-society tension is a zero-sum game (e.g., Shaw & Colimore, 1988), and in a zero-sum scenario, my individual needs can be met only at the expense of social concerns, and vice versa. What I get must be taken away from you. What you get diminishes me. This belief lies at the heart of what Maslow calls the jungle world. And it is a world in which my freedom and my needs are purchased at the price of yours. It is a world in which the best for which we can hope is a perpetual tension between my needs and yours, between individual and societal concerns. However, if contrasted with individualism, individuality comes out of a complex of meanings of the word individual, which stresses both a unique individual and his or her indivisible membership in a group (Grant, 1986). As Grant (1986) contends, if the opposite of individualism is socialism not conformity, and if instead the opposite of individuality is conformity, it becomes possible to be both uniquely individual and socioecologically embedded (Bowers & Flinders, 1990). If we can see ourselves on more than one continuum simultaneously, we become able to see how we can strive for and maintain our own unique individuality and also see ourselves as embedded in a society in the sense of a matrix of roles, needs, and responsibilities. It is only from such a perspective that we can cease to see our embedments and its resulting responsibilities as control, as not taking away from our individual freedom, and even seeing ourselves being potentially strong on both continua. From this perspective of individuality, it becomes possible to view synergy in the way that Maslow envisioned it, his conflation of individualism and individuality notwithstanding. Maslow had a vision of a world in which synergy is not a zerosum game but a way of interacting with the world, such that the social, political, and

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

51

cultural world becomes enhanced simultaneously with the enhancement of the individual. What is good for you is also good for me. When my needs are met, it need not take away from you but, indeed, can meet your needs as well; that which is good for one is (or can be) good for all, and vice versa. Being able to view myself as at the high end of both continua, that is, in individuality and in being embedded, makes such an enriching view of synergy possible. This is the kind of world that Maslow contrasts with the jungle world. Although Maslow focuses his own spectacles on individual efforts to resist cultural pressures, some critics tend to put the psychological concept of the individual out of focus in stressing cultural forces. Although his lenses are limited, Maslows journals make clear that he became increasingly preoccupied in the 1960s with social and political forces, concerned with shortcomings in his own theoretical framework, and was putting increasing emphasis on social psychology. In these journal writings, not long before his sudden death in 1970, his language, in criticizing the jungle world, sounds a lot like his criticsdescriptions of individualism, as he uses terms such as rivalry, competition, personal chauvinism, money, power status, domination, manipulation, and Social Darwinism (Lowry, 1979). At the same time, Maslow kept intact a sense of moral agency, not falling into nihilism. In spite of his confusion of the languages of individualism and individuality, his insistence on some intrinsic human attributes and a need for growth argue against the contention that all is power relationships. Whereas ideas of an essential self and of human growth can be used as a mechanism of control and rightly have been deconstructed by postmodern scholars, the concepts need to be deconstructed in a way that heeds Alcoffs (1988) warning that deconstructing everything leaves us nothing but negatives. For Maslow, despite the impact of social forces, we as individuals have a responsibility to contribute to the possibilities of intrinsic human attributes, with the human need for growth providing a generating force for engaging in a lifetime enterprise of self-creation that has consequences on others. To us, this concept of growth is more than disciplinary practice and an effect of power relations. That it can and often does become this is obvious. But that it is no more than this is not obvious. Growth as an exciting and rewarding process (as Dewey also viewed it) can be understood apart from the problem of essences. This does not mean that there are no unresolved questions such as growth toward what? or embedded in what? However, definitive answers to unresolved questions, especially in a pluralistic society with differing assumptions, are not necessary in order to act individually. What Maslow posits is that growth possibility within each of us that is being betrayed whenever we diminish each other. Had Maslow lived longer, we think the trajectory of his later thinking shows that he might have continued his growth in seeing the dangers of individualism while providing space for individuality and for responsibility to (not for) others. But to do so, Maslow would have had to do more than glide over dimensions of power, and so will those who see themselves as having humanistic leanings in adult education.

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

52

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORY AND PRACTICE

Our analysis highlights the ongoing philosophical tensions between individual and societal concerns that persist in U.S. adult education, a theme presented historically by Rose and ONeill (1997) and a theme receiving attention in recent reviews concerning learning theory (e.g., Caffarella & Merriam, 1999; Kilgore, 1999). In this final section, we emphasize three subthemes entailed in our analysis, ones that seem particularly pertinent for assessing humanistic possibilities for adult education: (a) confronting an overfocus on the self and reconnecting it to social contexts, (b) recognizing the realities of power and conflict but without losing the concepts of individuality and interdependence, and (c) being aware of existential dilemmas that may arise when putting theory into practice. Two recent articles in Adult Education Quarterly take us in a direction that parallels our own, at least part way. Jansen and Wildmeersch (1998) present a critique of self-actualization as a contemporary myth that is anchored in a global privatization of identity. The self is now disconnected from the public domain and concern for others in a world in which social moral frames of reference are eroded, and although there is increased freedom of lifestyles and values in this postmodern world, there is a troubling rootlessness. This kind of vacuum in societal values is reminiscent of the scholarship in social psychology at midcentury concerning anomie and Karen Horneys work, a perspective and mentoring from which Maslow drew in his own work, for example, The Disease of Valuelessness (Hoffman, 1999). Maslow would feel an affinity for the Jansen and Wildmeersch (1998) connection of selfreflection and self-responsibility to the social interdependencies people meet in the risk society, and that enable and restrict their chances for self-fulfillment (p. 222). And he could even feel comfortable with their proposed connection of self-actualization (away from the economization of social life) to participation in various social contexts and communities, like labor organizations and leisure unions, family and neighborhood life, religious and spiritual societies, social movements, and political parties (p. 225). We think, however, that a more complex concept of daily community and institutional life is needed, one that more fully faces pluralism and conflict. Although we emphasize the prospects of simultaneously being uniquely individual and socially embedded, and although we believe that there is no inherent dichotomy between self and social worlds (even an enhancement of both), we well recognize the experiential tensions in the realities of daily life. As Abowitz (1997) poses in her focus on the situated contextual nonideal in the confusion of contemporary space, How do we confront the messinessthe disagreements and strugglesof attempting to reach the ideal (p. 75)? This is the direction in which St. Clair (1998) goes in the Adult Education Quarterly article that pushes the idea of community as a mediating function between individual agency and social structure but that also

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

53

calls for recognition of the diversity that implies inevitable conflict and tension. Community as relationship for St. Clair means that

The complexity of postmodern politics of identity can be recognized without losing sight of the fact that communities represent the collective. The subject can be seen as if acting within a field of diverse and interweaving communities which reflect affiliation based on gender, employment, race, sexuality, and many other dimensions . . . we create and recreate ourselves, defining ourselves by constraint, but also in terms of possibility. (pp. 7-8)

We question, however, St. Clairs (1998) assumption that all of this can be effective whether in a five-person project . . . a social movement of 5,000 or a city of 500,000 (p. 8). Emerging literature on local public spaces points to the problem of preserving individuality in daily community and institutional life where there are large numbers. In raising this question, we are not implying that social action can be effective without large-scale perspectives. As Nicholson (1999) contends in her postmodern feminism (with Nancy Fraser, 1985), there is a need for large theoretical tools to address large political problems, but at the same time, there is a need for theory to be pragmatic, even to face fallibility. One dimension that may need to be faced is the potential tension between collective action and individuality. In an article by Schutz (1999) that draws insights from Hannah Arendt and Maxine Greene, the issue of size is confronted with a perspective that large numbers in collective action may encourage mass identities rather than pluralistic contributions. Arendt argues that public spaces should enhance the uniqueness of individuals while fostering collaborative efforts because individuality needs continual development in the face of the pressures of the normalized society. Such a process, however, entails potential dilemmas between self and others that do not go away. For example, there may be too much emphasis on uniqueness and conflict in a collaborative project when more commonality is needed for effectiveness, or there may be too much sameness and consensus that diminish needed distinct voices. And then there may be additional tension and ambiguity (as Greene points out) when we root our individual identity in memories of the past while trying to reconstruct ourselves through collective engagement for future-oriented social transformation. Facing such existential dilemmas are part of the ongoing tensions between possibilities for change in education and the reality of constraints. This is why Maslow, in spite of his scientific drive for universals, held out for pragmatic hope in education in the messy mix of prospects and problems of human freedom. The neverending tensions between quest and reality are why Quigley calls for small victories in place of grand solutions in his book on literacy education (Demetrion, 1999). Small victories can come (as we sometimes experience in classrooms) when adult educators create an ethos of individuality and interdependence rather than of individualism, an ethos of pluralism rather than of consensus.

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

54

ADULT EDUCATION QUARTERLY / November 1999

We end this discussion with an ultimate tension of self and others, a tension that Maslow, his followers, and even his critics seldom face. It is the dilemma of each of us having an authentic position about human freedom on which to stand and act and realizing that it is our position, not the position. Schutz (1999) portrays the paradoxical reciprocity between reflection and action, between theory and practice.

For those of us who accept that reality is socially constructed, it has become increasingly difficult to believe in descriptions of human actions that present themselves as somehow free-floating and cultureless. . . . The conceptualization of local public space that I have synthesized here may subtly reflect the white, educated, middleclass backgrounds of Arendt, Greene, and myself, despite the other individual, historical, gender, and cultural gulfs that separate us.

So in the end, we, too, have to confront the evitable bedrock of our own philosophical-cultural assumptions that underlie our own place to stand, act, reflectand writeas adult educators concerning the ongoing issues of the individual and society. And because of this inevitable reality, there is no grand entrance, no grand exit.

REFERENCES

Abowitz, K. (1997). Neglected aspects of the liberal-communitarian debate and implications of school communities. Educational Foundations, 11(2), 63-82. Alcoff, L. (1988). Cultural feminism versus poststructuralism: The identity crisis in feminist theory. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 13(3), 405-436. Arieli, Y. (1964). Individualism and nationalism in American ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. New York: Harper & Row. Boshier, R., & Pickard, L. (1979). Citation patterns of articles published in Adult Education 1968-1977. Adult Education, 30, 34-51. Bowers, C. A. (1987). Elements of a post-liberal theory of education. New York: Teachers College Press. Bowers, C. A., & Flinders, D. J. (1990). Responsive teaching: An ecological approach to classroom patterns of language, culture, and thought. New York: Teachers College Press. Buss, A. R. (1979). Humanistic psychology as liberal ideology: The socio-historical roots of Maslows theory of self-actualization. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 19(3), 43-55. Caffarella, R., & Merriam, S. (1999). Perspectives on adult learning: Framing our research. In Proceedings of Adult Education Research Conference (pp. 62-67). De Kalb: Northern Illinois University. Cotkin, G. (1990). William James, public philosopher. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Demetrion, G. (1999). The pragmatic reform vision of B. Allan Quigley in light of the indubitable facts. Adult Education Quarterly, 49(3), 162-173. Edwards, R., & Usher, R. (1997). University adult education in the postmodern moment: Trends and challenges. Adult Education Quarterly, 47(3/4), 153-168. Elias, J., & Merriam, S. (1995). Philosophical foundations of adult education. Malabar, FL: Kreiger. Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage.

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Pearson and Podeschi / HUMANISM AND INDIVIDUALISM

55

Fraser, N. (1985). Michel Foucault: A young conservative? Ethics, 96, 165-184. Grant, W. (1986). Individualism and the tensions in American culture. American Quarterly, 38(2), 311-318. Hoffman, E. (1999). The right to be humanA biography of Abraham Maslow. New York: McGrawHill. Jansen, T., & Wildemeersch, D. (1998). Beyond the myth of self-actualization: Reinventing the community perspective of adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(4), 216-226. Kilgore, D. (1999). Book review of Welton, M. (Ed.) (1995). In defense of the lifeworld: Critical perspectives on adult learning. Adult Education Quarterly, 49(2), 122-127. Lethbridge, D. (1986). A Marxist theory of self-actualization. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 26(2), 84-103. Lowry, R. (Ed.). (1979). The journals of A. H. Maslow. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Maslow, A. (1962). Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Maslow, A. (1971). The further reaches of human nature. New York: Viking. Muller, L. (1992). Progressivism and United States adult education: A critique of mainstream theory as embodied in the work of Malcolm Knowles. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Dissertation Services. Nicholson, L. (1999). The play of reason. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Pearson, E. (1994). A new look at Maslows humanism through radical and postmodern criticism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Dissertation Services. Podeschi, R. (1983). Maslows dance with philosophy. Journal of Thought, 18(4), 94-100. Podeschi, R. (1986). Philosophies, practices and American values. Lifelong Learning: An Omnibus of Practice and Research, 9(4), 4-6. Podeschi, R., & Pearson, E. (1986). Knowles and Maslow: Differences about freedom. Lifelong Learning: An Omnibus of Practice and Research, 9(7), 16-18. Podeschi, R., & Pearson, E. (1989). A review of the reviews: Habits of the heart. Educational Studies, 20(3), 342-351. Pratt, D. D. (1993). Andragogy after twenty-five years. In S. B. Merriam (Ed.), An update of adult learning theory: New directions for adult and continuing education, No. 57 (pp. 15-23). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Rabinow, P., & Dreyfus, H. (1983). Michel Foucault, beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rose, A. D., & ONeill, L. (1997). Reconciling claims for the individual and the community: Horace Kallen, cultural pluralism, and persistent tensions in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 47(3/4), 138-152. Schutz, A. (1999). Creating local public spaces in schools: Insights from Hannah Arendt and Maxine Greene. Curriculum Inquiry, 29(1), 77-98. Shaw, R., & Colimore, K. (1988). Humanistic psychology as ideology: An analysis of Maslows contradictions. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 28(3), 51-74. St. Clair, R. (1998). On the commonplace: Reclaiming community in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 49(1), 5-14. Stewart, E. (1979). American cultural patterns: A cross-cultural perspective. La Grange Park, IL: Intercultural Network. Taylor, C. (1986). Foucault: A critical reader (D. C. Hoy, Ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwood.

Downloaded from aeq.sagepub.com at National School of Political on January 17, 2013

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Brief History of Alternative Education by Ron MillerDocumento6 pagineA Brief History of Alternative Education by Ron MillerKristina Gay EsposoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan in The K To 12 Basic Education Curriculum and It's Implication To Pre-Service Teacher EducationDocumento5 pagineLesson Plan in The K To 12 Basic Education Curriculum and It's Implication To Pre-Service Teacher EducationJelly Marie Baya Flores67% (3)

- Contentious Curricula: Afrocentrism and Creationism in American Public SchoolsDa EverandContentious Curricula: Afrocentrism and Creationism in American Public SchoolsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Post Modernism and EducationDocumento11 paginePost Modernism and EducationElijah James LegaspiNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2: Critical Theory and PedagogyDocumento20 pagineUnit 2: Critical Theory and PedagogyBint e HawwaNessuna valutazione finora

- BAL, Mieke - Semiotics and Art HistoryDocumento36 pagineBAL, Mieke - Semiotics and Art HistoryEnrique Esquer100% (1)

- Is College For Everyone - RevisedDocumento5 pagineIs College For Everyone - Revisedapi-295480043Nessuna valutazione finora

- Williams, C. Beam, S. (2019) Technology and Writing Review of ResearchDocumento16 pagineWilliams, C. Beam, S. (2019) Technology and Writing Review of ResearchAngélica Rocío RestrepoNessuna valutazione finora

- Laboratories and Rat Boxes: A Literary History of Organic and Mechanistic Models of EducationDa EverandLaboratories and Rat Boxes: A Literary History of Organic and Mechanistic Models of EducationValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Social Theory in The Function of EducationDocumento10 pagineSocial Theory in The Function of EducationMichael Phan75% (4)

- The School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismDa EverandThe School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismNessuna valutazione finora

- Self Esteem Critical ReviewDocumento26 pagineSelf Esteem Critical Reviewkeycastro509Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Crisis of American Education and Reforms Proposals According To Allan BloomDocumento17 pagineThe Crisis of American Education and Reforms Proposals According To Allan BloomRamón CardozoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On Ensuring Holistic Education in Community by Participatory ApproachDocumento10 pagineA Study On Ensuring Holistic Education in Community by Participatory ApproachrajeshsamodajatNessuna valutazione finora

- Cutting ClassDocumento70 pagineCutting ClassQueenee Ibrahim100% (1)

- Maxine Green Social Reconstructionist Frontier Marx Education NTRDocumento12 pagineMaxine Green Social Reconstructionist Frontier Marx Education NTRCOCNessuna valutazione finora

- American Sociological AssociationDocumento15 pagineAmerican Sociological AssociationMubashir QureshiNessuna valutazione finora

- CultureDocumento14 pagineCultureJenny Marcela CastilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Discourse, Identity, and Community - Abbas BarzegarDocumento28 pagineDiscourse, Identity, and Community - Abbas BarzegarNiaz HannanNessuna valutazione finora

- Functionalist TheoryDocumento6 pagineFunctionalist Theoryanon_877103538Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bruce Fuller, Emily Hannum Schooling and Social Capital in Diverse Cultures, Volume 13 Research in Sociology of Education 2002Documento187 pagineBruce Fuller, Emily Hannum Schooling and Social Capital in Diverse Cultures, Volume 13 Research in Sociology of Education 2002Elif BaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gottlieb 1975Documento3 pagineGottlieb 1975ordaniniNessuna valutazione finora

- In the Crossfire: Marcus Foster and the Troubled History of American School ReformDa EverandIn the Crossfire: Marcus Foster and the Troubled History of American School ReformNessuna valutazione finora

- Muda, The Mirror Image Chapter 2 - The Contemporary Social Context, WomenDocumento30 pagineMuda, The Mirror Image Chapter 2 - The Contemporary Social Context, WomenSirea SuárezNessuna valutazione finora

- Socialization in Media: Normalized) Within A Society. Many Socio-Political Theories Postulate That Socialization ProvidesDocumento4 pagineSocialization in Media: Normalized) Within A Society. Many Socio-Political Theories Postulate That Socialization ProvidesarjunwilNessuna valutazione finora

- c2 PDFDocumento26 paginec2 PDFIsolda Alanna RlNessuna valutazione finora

- Theory Contemporary Sociological PerspectivesDocumento5 pagineTheory Contemporary Sociological PerspectivesCorwin DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- Popular Education and Social ChangeDocumento10 paginePopular Education and Social ChangeOscar JaraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Systemic Racism On Quarter-Life Crisis in The Autobiography of Malcolm X (As Told To Alex Haley)Documento9 pagineThe Influence of Systemic Racism On Quarter-Life Crisis in The Autobiography of Malcolm X (As Told To Alex Haley)IJELS Research Journal100% (1)

- Political Tolerance Culture and The Individual in ZimbabweDocumento9 paginePolitical Tolerance Culture and The Individual in ZimbabweTapiwa ZhouNessuna valutazione finora

- Anthropology of EducationDocumento12 pagineAnthropology of EducationdimfaNessuna valutazione finora

- Freefall of the American University: How Our Colleges Are Corrupting the Minds and Morals of the Next GenerationDa EverandFreefall of the American University: How Our Colleges Are Corrupting the Minds and Morals of the Next GenerationValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- The Assault Against Logic by Steve YatesDocumento28 pagineThe Assault Against Logic by Steve YatesDeea MilanNessuna valutazione finora

- Hervé Varenne-Culture, Education, AnthropologyDocumento23 pagineHervé Varenne-Culture, Education, Anthropologyol giNessuna valutazione finora

- FinalDocumento6 pagineFinalMng VctrnNessuna valutazione finora

- EFF 210 Sociological Perspectives On Education 06.10.2014Documento2 pagineEFF 210 Sociological Perspectives On Education 06.10.2014Pabalelo Gaofenngwe SefakoNessuna valutazione finora

- Civic Education (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Documento23 pagineCivic Education (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)4ieenereNessuna valutazione finora

- Ituralde GuzaremDocumento10 pagineIturalde GuzaremEman NolascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Media For Social Justice in Adult Education: A Critical Theoretical FrameworkDocumento14 pagineSocial Media For Social Justice in Adult Education: A Critical Theoretical Frameworkvinoelnino10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Music in MovementsDocumento17 pagineMusic in MovementsChibi_MeztliNessuna valutazione finora

- Another World Is PossibleDocumento16 pagineAnother World Is PossibleJavier PNessuna valutazione finora

- Peter L.callero. The Sociology of The SelfDocumento21 paginePeter L.callero. The Sociology of The SelfcrmollNessuna valutazione finora

- (1994) 超越文化认同Documento25 pagine(1994) 超越文化认同张苡铭Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sociological Perspectives On Socialization: August 2018Documento23 pagineSociological Perspectives On Socialization: August 2018Bokou KhalfaNessuna valutazione finora

- Amstud - Nana - Final PaperDocumento9 pagineAmstud - Nana - Final PaperKALONIKA IVANA WIDODONessuna valutazione finora

- Theory Paper 2Documento7 pagineTheory Paper 2api-483917490Nessuna valutazione finora

- Haste (2004) Constructing The CitizenDocumento29 pagineHaste (2004) Constructing The CitizenaldocordobaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedagogy of The OppressedDocumento4 paginePedagogy of The OppressedVic Awdrey BarisNessuna valutazione finora

- Critical Pedagogy and Social WorkDocumento8 pagineCritical Pedagogy and Social WorkdonnakishotNessuna valutazione finora

- Music-in-Movement-Cultural and-New-Social-Movements-by-Ron-EyermanDocumento16 pagineMusic-in-Movement-Cultural and-New-Social-Movements-by-Ron-EyermanEmerson Ferreira BezerraNessuna valutazione finora

- How Goes it With America: In the Interests of Educational and Societal ReformDa EverandHow Goes it With America: In the Interests of Educational and Societal ReformNessuna valutazione finora

- Essays On DisciplineDocumento3 pagineEssays On Disciplinef1silylymef2100% (2)

- Individualism-Collectivism Meta-Analyses PDFDocumento70 pagineIndividualism-Collectivism Meta-Analyses PDFpelelemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rethinking Individualism and CollectivismDocumento70 pagineRethinking Individualism and CollectivismPersephona13100% (1)

- Universal LiberalismDocumento13 pagineUniversal LiberalismArmin NiknamNessuna valutazione finora

- Artículo en InglésDocumento10 pagineArtículo en InglésHablar Mejor FrancésNessuna valutazione finora

- 008 Buku Penerangan KSSRDocumento20 pagine008 Buku Penerangan KSSRmedulaoblongata83Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment No.2 Course: Foundations of Education (6500) Semester: Spring, 2015 Level: MA/M.EdDocumento23 pagineAssignment No.2 Course: Foundations of Education (6500) Semester: Spring, 2015 Level: MA/M.Edmc090201003Nessuna valutazione finora

- "We Are Poor, Not Stupid": Learning From Autonomous Grassroots Social Movements in South AfricaDocumento56 pagine"We Are Poor, Not Stupid": Learning From Autonomous Grassroots Social Movements in South AfricaTigersEye99Nessuna valutazione finora

- Studying Conflict TheoryDocumento10 pagineStudying Conflict TheoryEman NolascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Sardoc 2021 - The Language of Neoliberal EducationDocumento8 pagineSardoc 2021 - The Language of Neoliberal EducationFanni LeczkésiNessuna valutazione finora

- Youthtopias: Towards A New Paradigm of Critical Youth Studies A.A. Akom, Julio Cammarota, and Shawn GinwrightDocumento30 pagineYouthtopias: Towards A New Paradigm of Critical Youth Studies A.A. Akom, Julio Cammarota, and Shawn GinwrightUrbanYouthJusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- JCEPSCritical PedagogyarticleDocumento36 pagineJCEPSCritical PedagogyarticleMilos JankovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Creating Brand Loyalty in Post-Recession EconomyDocumento3 pagineCreating Brand Loyalty in Post-Recession EconomyGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study - FiatDocumento54 pagineCase Study - Fiatprit_shuk100% (3)

- Brand Orientation - ADocumento15 pagineBrand Orientation - AGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- 33 Brands ManagementDocumento8 pagine33 Brands ManagementGaurav ChoudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rafferty Griffin LQDocumento26 pagineRafferty Griffin LQGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- Admitere MasterDocumento1 paginaAdmitere MasterGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005SALANOVA06AIDocumento11 pagine2005SALANOVA06AIGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- 325 FullDocumento17 pagine325 FullGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- Admitere MasterDocumento1 paginaAdmitere MasterGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- MotivatieDocumento24 pagineMotivatieGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005SALANOVA06AIDocumento11 pagine2005SALANOVA06AIGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- Media Effects WebDocumento6 pagineMedia Effects WebArsene Diana SelenaNessuna valutazione finora

- 52 2 5Documento8 pagine52 2 5Gina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- 53 FullDocumento28 pagine53 FullGina Beatrice Pană0% (1)

- MotivatieDocumento24 pagineMotivatieGina Beatrice PanăNessuna valutazione finora

- The Social Impacts of Information and Communication Technology in NigeriaDocumento6 pagineThe Social Impacts of Information and Communication Technology in NigeriaCouple BookNessuna valutazione finora

- Bản Sao Của FC3 - Workbook 3ADocumento52 pagineBản Sao Của FC3 - Workbook 3ABi NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are The Major Distinction Between Storage and MemoryDocumento5 pagineWhat Are The Major Distinction Between Storage and MemoryBimboy CuenoNessuna valutazione finora

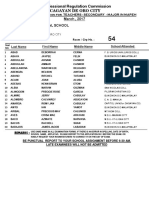

- Q3 Summative 1Documento24 pagineQ3 Summative 1Nilnen Fernandez100% (1)

- Burson-Martsteller ProposalDocumento20 pagineBurson-Martsteller ProposalcallertimesNessuna valutazione finora

- Science Lesson Plan Uv BeadsDocumento4 pagineScience Lesson Plan Uv Beadsapi-259165264Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group Discussion TopicsDocumento7 pagineGroup Discussion TopicsRahul KotagiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Mapeh PDFDocumento11 pagineMapeh PDFPRC BoardNessuna valutazione finora

- DMD 3062 - Final Year Project IDocumento10 pagineDMD 3062 - Final Year Project IShafiq KhaleedNessuna valutazione finora

- Proiect KA210-ADU-F5B6C4F1 (4) (1) EnglezaDocumento40 pagineProiect KA210-ADU-F5B6C4F1 (4) (1) EnglezaIonella Iuliana Diana ChiricaNessuna valutazione finora

- BehaviourismDocumento30 pagineBehaviourismAsma Riaz0% (1)

- Developing of Material For Language Teaching p006Documento1 paginaDeveloping of Material For Language Teaching p006ahmad100% (1)

- Unit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacDocumento2 pagineUnit 1 Function Lesson Plan First Year BacMohammedBaouaisseNessuna valutazione finora

- What Elementary Teachers Need To Know About Language Lily Wong FillmoreDocumento2 pagineWhat Elementary Teachers Need To Know About Language Lily Wong Fillmorekaren clarkNessuna valutazione finora

- Example How To Email German UniversitiesDocumento2 pagineExample How To Email German UniversitiesKhaled AmrNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading ReferenceDocumento4 pagineReading ReferenceRaffy CorpuzNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Education: San Jose Provincial High SchoolDocumento3 pagineDepartment of Education: San Jose Provincial High SchoolStephanie100% (1)

- The Study of ChromaticismDocumento31 pagineThe Study of ChromaticismSimonTrentSmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Modu6 SimilarityDocumento81 pagineModu6 SimilarityCyanosus CorderoNessuna valutazione finora

- Realism: Subjective Long QuestionsDocumento11 pagineRealism: Subjective Long QuestionsAnam RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- AO1.2 - Poster EssayDocumento5 pagineAO1.2 - Poster EssayHeart EspineliNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Outline Pagtuturo NG Filipino Sa Elementarya IDocumento5 pagineCourse Outline Pagtuturo NG Filipino Sa Elementarya IElma CapilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 1 Human Behavior and VictimologyDocumento17 pagineWeek 1 Human Behavior and VictimologyLhen Demesa LlunadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cvonline - Hu Angol Oneletrajz MintaDocumento1 paginaCvonline - Hu Angol Oneletrajz MintaMárta FábiánNessuna valutazione finora

- Kray-Leading Through Negotiation - CMR 2007Documento16 pagineKray-Leading Through Negotiation - CMR 2007Rishita Rai0% (2)

- Gen Math GAS Daily Lesson LogDocumento5 pagineGen Math GAS Daily Lesson Logjun del rosario100% (2)