Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

E. McGrath, 'Rubens's Musathena'

Caricato da

Claudio CastellettiCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

E. McGrath, 'Rubens's Musathena'

Caricato da

Claudio CastellettiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

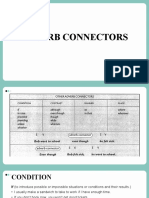

Rubens's Musathena Author(s): Elizabeth McGrath Source: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 50 (1987), pp.

233-245 Published by: The Warburg Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/751332 . Accessed: 11/04/2013 05:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Warburg Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA RUBENS'S MUSA THENA

233

N AUGUST 1617 the Jesuit Bernard Bauhuis (Bauhusius) wrote to Balthasar Moretus expressing the hope that the new edition of his which the latterwas about poems (epigrammata) to publish mightbe adorned with some kind of illustrated title-page. Heinsius's poems were gettingthis treatment,as were those of Father Surius just published at Arras, and the Plantin Press had already given such a title-pageto the meditations of the Jesuit Father Provincial as well as to other works. It was a wonderfully diverting ornament, attracted the buyer, and made littledifference to the price. Bauhuis was confidentthat Rubens with his divinum ingenium would be able to devise something that would be suitable both to his poetry and to his religious situation,. The books he had in mind must have been various devotional works by Frans de Costere (currently Belgian Father Provincial) which had been printed by Plantin in the I580s,2 Joannes Surius's Morata Poesis (Arras 1617) (introduced grandiloquently by figuresof Plato and Aristotle), and, in particular, Daniel Heinsius's Poemata.The edition of the Latin poems of Heinsius published at Leyden in 1613 had been given a title-pagewith Hercules and Minerva holding a laurel wreath above Pegasus,3 while his vernacular poems,

I should like to thankBrendan Cassidy, Charles Hope, Jill Kraye and especially Ruth Rubinstein forhelpful commentsand criticism.

S'In fronte libri,mi Morete, plures sunt, qui iconem videmus. aliquam desiderant.(Ita enimpassim iam fieri Ita Heinsii prodeunt, ita nuper P. Surii carmina He also added at the side: 'Note that the Muse Atrebati prodierunt. Ita quoque vos ipsi fecistis in has a featheron her head, which is how she is meditationibus R. P. Provincialisnostrialiisque libris.) Mire enim lectorem recreat, Emtorem allicit, librum ornat, neque pretium multum auget.... D. Rubenius divinoillo ingeniosuo inveniet scio aliquid appositurum et lauro meae conveniens, et ordini in quo sum, et Pietati.' For the whole letter(withtranslation)seeJ. R. and Judson and Carl Van de Velde, Book Illustrations 4 'Excogitavi Parnassum sacrum, Musas, MnemosyTitle-pages(Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, nem,Apollinem,omnia sacra, etc.' See Judson-Van de of 12 October 1617). xxI), London and Philadelphia 1978 (hereafterJudson- Velde, i, pp. 367-68, doc. 9 (letter Van de Velde), nI,pp. 366-67, doc. 8 (letterof I August I have not translatedsaceras 'sacred, holy', to avoid a Christian implication which I thinkBauhuis did not I617). 2 De vita et laudibus Deiparae Virginismeditationesintend;he was probably using the word in its primary dominicae Passionis sense of'consecratedto a deity'. quinquaginta historia (1587), De universa meditationes AveMaris quinquaginta (1587) and In hymnum s For the printedtitle-page(by Charles de Mallery?), as well as the editionsof the book, see Judson-Van de Stellameditationes (1589). ofthe forthcom- Velde, I, pp. 268-71, no. 63; 1, fig. 215. Cf. H.J. Duffy in 3 Bauhuis cannot have been thinking ing 1617 Leyden edition, since this did not have an Rubens and theBook,ed. J. S. Held, cat. exh. Williamsillustrated town Mass. 1977, PP. 56-58, no. 4 and fig. 50. title-page.

and Courtauld Volume 5o, I1987 Institutes, Journalof theWarburg

the Nederduytsche Poemata (Amsterdam 1616), had been still more elegantly prefaced by an illustration of Apollo with his lyre between ?Calliope (above a scene ofHelicon) and Venus (above Parnassus). Indeed it was perhaps this last design which prompted the letter to Moretus two months later, in which Bauhuis proposed an idea forthe general theme: 'I have thought of hallowed Parnassus, the Muses, Mnemosyne, all the thingsassociated with the gods etc.'4 In the event the second edition of the epigrams of this popular author appeared posthumously in I620, and without a Rubens title-page,as did the volumes of I620 and 1623 which combined the poems with those of two other Jesuits, Jacob Biderman and Baldwin Cabilliau. But when in 1634 Bauhuis was reprinted,thistimein the company ofCabilliau and another member of his Order, Charles Malapert, Rubens produced a design (P1. 65b) which seems to be a witty response to the original Parnassus suggestion,s much better contrivedtoo than a mountain fullofgods to fit the small scale of a 240 page. At any rate, we have it fromthe artist himselfthat he thought his design quite a clever one. In a note written on the drawing (P1. 65a) which he sent for approval to his old friend Moretus, Rubens wrote: You have herethe Muse or Poetry and Minervaor Virtue in theform ofa Hermathena. joined together For I have put the Muse insteadof Mercury which can be justified on thebasis ofseveralprecedents. I don't knowwhether I you will like myfabrication. mustsay, though, thatI'm reallypleased withthis invention of mine- indeed I almostcongratulate on it. myself

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

234

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS

ancient art and ancient literature.9Like Vasari and Raphael, Rubens gave his muse a laurel wreath and lyre; her instrument,however, has three strings, as had the first ancient lyres, according to Diodorus Siculus.'o But lyre and laurel crown are likewise the attributes of or Musagetes;indeed the Apollo as Citharoedus in hair style(long), dress and attitude similarity between Apollo got up in his singing costume and the Muses of poetry was familiar to scholars, particularlyfrom seventeenth-century images on gems and coins (P1. 66a)," and

9 As regardsthe provinceof individualMuses, Erato, forexample,is normally connectedwithlove poetry(cf. 259D; Ovid, De arteamandi, e.g. Plato, Phaedrus, n, 425 and Fasti,Iv, 195), but Virgilcan invokeherinspiration forheroic verse,just as he does Calliope's (Aeneid, vii, imaginibus quaestiones 37; IX,525). See O. Bie, De Musarum 6 'Habes hic Musam sive Poesim cum Minerva seu diss. Berlin 1887, esp. pp. 2o-3I; also Wegner selectae, VirtuteformaHermatenis coniunctam[;] nam musam (as in n.7), pp. 93-I 10o. Cf. L.G. Gyraldus, De deis Basle 1548, esp. pp. 358-60; also the same pro Mercurio apposui quod pluribus exemplis licet, gentium, nescio an tibi meum commentumplacebit[.] Ego certe author's De musis (as in n. 7) of 1539. For the syntagma mihihoc inventovalde placeo ne dicam gratulor'.'Nota varied iconographyof individual Muses in ancient art ab see Wegner, loc. cit. and esp. L. P. Faedo, 'Sarcofagi quod Musa habeat Pennam in capite qua differt romani con muse', Aufstieg undNiedergang derromischen Apolline'. See Judson-Van de Velde, I, pp. 270-71, Berlinand New York I1981, no. 63a; n, fig.214; J. S. Held, Rubens. Selected I, 12,ii (Principat), pp. Drazwings, Welt, London, 1959, I, p. 154, no. 153; n, pl. 159 (p. 153, 65-155, esp. 65-77; and, fora discussion in the lightof edition ancient images known in the i7th century, B. de no. 251 and pl. 221Iin therevised,single-volume in Sculpfrom Montfaucon,Antiquity and Represented is slightly different [Oxford1986]). My translation Explained tr. D. Humphreys,London I721-22 and Supplethat of Held (followedbyJudson and Van de Velde), tures, 1725,I, pp. 67-7I and pls 28-32. though not in sense, except perhaps in rendering ment, Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca commentum 'contrivance'or 'fiction',ratherthan 'idea'. o10 I, 16, I; cf.the historica, E. H. Gombrichinforms me thatthe use ofan arrow to discussionofthe meaningof the 3-stringed lyrein G. P. as well Valeriano, Hieroglyphica, edn Basle '575, fol.348'rv;also directattention (presumablythatoftheengraver deplatte des ou Tableaux Les Images be something B. de Vigenbre, as thepublisher)to thefeather, peinture may itself of an innovation;the use of the directionalarrow was deuxPhilostrates ..., Paris I614, p. 87. For ancient 3delivered stringedlyreson Roman coins verysimilar in formto discussed in his lecture'PictorialInstructions' at the symposiumImages and Understanding In, (Rank Prize Rubens's see Montfaucon (as in n. 9), Supplement, Organization), London, October 1986 (to be published pl. 68 (3, 32). " de la religion See, forexample, G. du Choul, Discours Press). by Cambridge University Romains..., edn Lyons 1581, pp. 204-07, 79; Plato, Phaedrus,259D. For des anciens 7Hesiod, Theogony, see in general L. G. Gyraldus, 212-14, esp. p. 204 with the coin of Antoninus Pius Calliope's pre-eminence De musis in HerculisVitaetc.,Basle I539, pp. inscribedApolliniAugusto (actually a Muse?; cf. E. Q. syntagma, Milan 1818-22, I, pp. Cf. M. Wegner, Die Musensarkophage, Die Visconti,II MuseoPio Clementino, IIo--I2. Montfaucon(as in n. 9), i, pp. AntikenSarkophagreliefs, v, 3, Berlin 1966, pp. 98-99, 143-44). Also, generally, Io9. It is especially relevant to Rubens's conceit (cf. 62-71, esp. 64, 65 and pl. 26 (16-I7) for figuresof heads, some ofwhich,as below, nn. 85, 86) that his friendErycius Puteanus, in Apollo; cf.the laurel-crowned his Musathena, siveNotarum Heptas (Hanover I602, pp. Montfaucon remarks,have female hairstylesin pl. 26 16-18) chose Calliope as the obvious Muse to stand for (5-8, Io, I I). In I6th c. drawingsof the puteal, now in themall, so that he did not need to drag the whole lot the Louvre, which shows Bacchic dancers with an as thelatteris sometimes down from heaven (cf. p. i6: 'Sed ne ad constituendam Apollo Citharoedus, represented MUSATHENAM universum coetum coelo traham, a Muse (e.g. by Dosio: C. Hiilsen, Das Skizzenbuch des Dosio im staatlichen Giovannantonio solam Calliopen evocabo'). Kupferstichkabinett zu Berlin 1933, PP. 5-6, fol.8' and pl. x, I9). (The 8 In this painting of 1555-58, Calliope has the Berlin, attributes of all the otherMuses on or around her: see full-scalesculpturesrecognizedas Apollo Citharoedus in e i Medici, the Renaissance seem to have shownhim not in his long E. Allegri and A. Cecchi, Palazzo Vecchio Florence 1980,pp. 80-8 I, quotingVasari's own descrip- gown,but nearlynude, and therefore easilydistinguishable froma Muse. Cf. P. P. Bober and R. Rubinstein, tion,and fig.p. 81.

distinguished fromApollo', using an arrow to draw attentionto the relevantattribute.6 Rubens had good reason to point out the Muse's identifyingfeather. He had characterized her as 'Musa sive Poesis', indicating that he meant her to representpoetic inspiration in general, like Raphael's famous Poesia on the ceiling of the Stanza della Segnatura. He may have thoughtof her as Calliope, the oldest and principal Muse, whom Hesiod and Plato had set above the others,' and whom Vasari made the representative of all nine in his ofthe Palazzo Vecchio;8 painting forthescrittoio but he must have been aware of the blurred distinctionsbetween attributesand even areas of patronage of individual Muses in both

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA

would later give rise to heated debate when the famous Barberini Muse was pronounced an Muses alone, however, Apollo Citharoedus.12 wear feathers, and do - from one to three apiece - on ancient Roman statues and reliefs. Several of these were undoubtedly known to Rubens and provided the source for his attribute. There were, for example, the three Muses each with two feathers, described by Aldrovandi in 1556 in Pietrode Radicibus's collection at Rome,13 and the Muse with three feathers drawn by Giovannantonio Dosio in the Vatican.14 There were also several sarcophagi

235

no. 75, pl. 5; Montfaucon, I, p. 69, pl. 30 [I]), which Montfaucon calls Polyhymnia and Wegner Terplike an Apollo Musagetes. sichore,is particularly 12This statue, discovered in 1678, was identifiedby Winckelmann with the Erato by Ageladas, Phidias's master, but is now always called Apollo. See A. FurtderGlyptothek Beschreibung Kiinig Ludwig'sI. zu waingler, Munich 1900, pp. 185-91, no. 21II. Cf. the Miinchen, comments by Visconti (as in n. II, I, pp. 143-45) in rejecting the then current identificationof another statue (his pl. xxII: with long dress, lyre and laurel wreath) as a Muse and arguing against Winckelmann thatit is Apollo Citharoedus. chepertutta Roma 13 U. Aldrovandi, Delle statue antiche, in L. Mauro, Le antichita dela Cittai di Roma, .. si veggono Venice 1556, p. 142. Another2-feathered Muse drawn by Dosio in the Bufalo collection(Hiilsen [as in n. I I], pp. 28, fol.59 and pl. LXXVIII)is now in the Uffizi, featherless:she lost her headdress when she was reforthe Niobid groupin 1583 (cf.H. Wrede,Der restored derdel Bufalobei derFontanaTrevi, Trierer Antikengarten WinckelmannsprogrammIv, Mainz 1982, pp. 7, 22 (n. 55) and pl. 7, I). 14 Hiilsen (as in n. ii1), pp. 45-46, fol. i49r. and pl. cxxvI. Accordingto Hiilsen the statue was brought to the Capitol in 1566; it is not,however,identicalwith theone he citesin theMuseo Capitolino. This is actually the'JunoLucina' with3 feathers whichAldrovandi(op. cit., p. I8I) mentionsas in the Lisca collection:she was also a Muse, who in thiscase had preservedher ancient attributebut had been restoredwith roses (forJuno); now in the Museo Capitolino, she still carries her Renaissance flowers(cf. H. StuartJones,A Catalogue of Ancient in theMunicipalCollections Sculptures preserved of Rome.I: The Sculptures Oxford of theMuseo Capitolino, 1912, P. 298, no. 35; pl. 73; also P. P. Bober, 'Francesco Lisca's Collection ofAntiquities',Essaysin the History of Artpresented toRudolfWittkower, London and New York 1967,p. 120).

showing feathered Muses with Apollo, Minerva, and/or a poet or poetess.1s Examples known in the Renaissance in which the Muses, like Rubens's, wear a single featherare in the Palazzo Rospigliosi, the Palazzo Mattei, Woburn Abbey (P1. 66b) and the Villa Aldrovandi imagined that the Medici.16 feathers expressed the Muses' power to give flight to those the poets celebrate, or else themselves to rise up on the ingegniof the poets,"7ideas which later archaeologists would dismiss as 'capricious speculations'.1s The prosaic explanation, recorded principally, if in Pausanias, was that the Muses won briefly, crowns offeathersafterdefeatingthe Sirens in a singing contest, and plucking their wings.19 Renaissance Artists and AntiqueSculpture. A Handbook of since Eustathius, commenting on However, London and Oxford I986, pp. 76-77, under Sources, connects this no. 35 [cf. fig.35]). And for comparable Muses see Homer's famous epea pteroenta, musical with the trophy words', poet's 'winged the Muse with laurel crown Montfaucon,I, pls 29-30; it is easy to see how Aldrovandi arrived at his and lyreor barbiton in the sarcophagus drawn forDal Pozzo and now in Paris (Wegner [as in n. 7], pp. 36-37, conceit.20At any rate the defeat of the Sirens is

See Wegner (as in n. 7), passim, esp. pp. 71-72, no. s15 183, pls 36a, 44b, 46a, 49b (in S. Maria in Aventino, Rome; copied by Aspertini); pp. 27-28, no. 55, pls 24, 25, 41b, 137d-e (Munich, Glyptothek, Albani formerly collection, copied in Codex Coburgensis and Codex Pighianus) (both 2 featherseach); pp. 57-58, no. 138, pl. 68 (Vatican, copies in Codex Pighianus: 3 feathers each). In generalsee M. Bottariand N. Foggini,II Museo Milan 1819-2 I, IIIr, Capitolino, pp. 234-37. 16 Wegner (as in n. 7), pp. 66-67, no. 170, pls 37a, 39, 40 (Palazzo Rospigliosi;drawn in Codex Pighianus and Codex Coburgensis); p. 66, no. 168, pl. 150 (Palazzo Mattei; firstrecorded in G.R. Amaduzzi, Monumenta Matthaeiorum, IIn, Rome 1778, pl.49, I); pp. 9-91, no. 231, pls 33b, 34, 42a, 43b, 45a (Woburn Abbey; drawn forDal Pozzo) (P1. 66b); p.82, no. 215, pls 27a, 29, 30, 43a (Villa Medici). 17 Aldrovandi,loc. cit. in n. 13. 1s See Visconti (as in n. Ii), I, p. 162; cf. Bottari and Foggini (as in n. 15), PP. 235-36. ni,778; 19 Pausanias, Ix, 34, cf. Eustathius, 1709 on Odyssey, xII, 167,and 85 on Iliad, I, 201. 20 Eustathius, 85 (on Iliad,I, 201I).He also relatesthisto Vasari gave his wingson theMuses' heads: theattribute Calliope.For Eustathiusand Pausanias see Gyraldus,De deisgentium (as in n. 9), P. 240; De musis(as in n. 7) PP. I 4-15 (where the wingson the head are not,however, mentioned); Valeriano (as in n. Io), fol. 55r ('Accipiter:victoriagloriave'); N. Conti, Mythologia, edn Padua (Tozzi) 1616, p. 395; and (for an edition of Homer which Rubens probably used) Homer, [Opera] quae exstant omnia,ed. J. Spondanus, Basle 1606, ni, p. 173. A. Furtwinglerin factproposed thattheSiren story was a late invention to account for the Muses' feathers, which reallyderived fromHermes, god of wisdom and inventor oflanguage - a theory notperhaps so different

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

236

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS

I550s in the Palazzo Firenze, Rome, Prospero Fontana had in fact shown the Muses wearing one white feather each, presumably from the earlier Siren victory.25 But differently coloured feathersdecorated the heads ofthe Muses in the Florentine festivals of 1565 and I589, on the authorityof Cartari's Imagini(1 556).26 And the influential Cartari was behind the most distinguished feathered Muse of the sixteenth century,that painted by Veronese in the Villa Maser.27 Yet the Barbaro, despite the Muse's feather(s) remained mythographers a rarity,28 and those artistsbeforeRubens who

graphically illustrated on an ancient sarcophagus which in I6Io was in the Villa Nera gardens in Rome (P1. 66d), and which was drawn forCassiano dal Pozzo.21 Here various stages in the contest are shown in sequence the Sirens ultimatelylosing singing dresses as well as feathers- and the Muses, even at the outset,already sport the supposed trophy.Still, in the absence of any other literaryor artistic accounts of the Siren contest, and given that Ovid in the Metamorphoses describes by contrast the defeat by the Muses of the Pierides in graphic detail,22 it was natural that Renaissance mythographers,aware of the featherson ancient statues of Muses, should have connected the attribute equally to this other musical event - thus sanctioning a multi-coloured headdress, since the Pierides had been changed into magpies.23 The antiquarian Antonio Agustin objected that the Muses could not have taken their attribute from the Pierides, whose feathers were acquired only after defeat; the Sirens for their part had birds' legs and wings before their competition, which in any case And in his must have been the Muses' first.24 Contest ofMusesand Pierides, painted in the early

eds J. Sieveking fromAldrovandi's. See KleineSchriften, and L. Curtius, Munich 1912-I3, II, pp. 357-58; Wegner (as in n. 7), p. I 16. 21 New York, Metropolitan Museum. See C.C. Vermeule, 'The Dal Pozzo-Albani Drawings of Classical of the Antiquitiesin the British Museum', Transactions American Society, Philosophical N.s., L, 5, I960, fol.2, no. 2 Artand theClassicalPast, and pl. p. 39; idem., European Cambridge, Mass. 1964,p. 5 and fig.3; and Wegner (as in n. 7), pp. 31-32, no. 6o, pl. 86c. The few other ofthesubject (Wegner,pp. 35 and I 16) representations are unlikely to have been knownin the I7th century. 22 Metamorphoses, v, 294-678 passim. 23 See Gyraldus, De deisgentium (as in n. 9), pp. 240, seen ancientstatueswhich 358, adding thathe has often in the head, supposedlyfromthe Sirens. have a feather ('Certe harum [=Musarum] signa hodie quoque pervetusta Romae visuntur,quae pennam habent in verticeaffixam, ut ipse saepe conspexi, quae Sirenum esse creduntur'.) The statues are not mentioned in on theMuses (op. cit.in n. 7), Gyraldus'searliertreatise whichis otherwise moredetailed than thechapterin the 1548 book. Lomazzo likewise refersthe Muses with a feathernot only to Pausanias but to 'statues in Rome' (G.P. Lomazzo, Scrittisulle arte, ed. R.P. Ciardi, Florence I973-74, ii, p. 518). But this information Gyraldus,as probablydoes thatin simplyderivesfrom Cartari,forwhom see below, n. 26. 24 Dialoghidi Don Antonio alle medaglie . . . intorno Agostini ...,edn Rome 1592,p. 157.

25 For the decorationof thispalace and an illustration of the paintingsee A. Nova, 'Bartolomeo Ammanati e Prospero Fontana a Palazzo Firenze. Architetturae emblemi per Giulio III Del Monte', Ricerche di Storia dell'arte, xxI, I983, pp. 53-76, esp. pp. 66-67 and fig.20; also B. F. Davidson, 'Perino del Vaga e La Sua Cerchia: Addenda and Corrigenda', MasterDrawings, vII, 1969, pp. 405-07 and fig.I; an earlydrawingforthispicturein Chatsworth(inv. 1332; cf. Davidson, p. 409, n. 15) in which some of the Pierides have already turned into magpies, does not yet show the Muses with feathers. Presumably the imagerywas derived fromGyraldus, who as Nova pointsout (p. 66) seems to have been used elsewherefortheiconography. 26 In the Mascherata of 1565 the Muses followed Cartari's recommendation'che cingevano loro il capo con penne di diversicolori' (V. Cartari,Le Imagini conla de i dei de gli antichi, Venice 1556, fol. I6'), spozitione over the victory althoughthiswas said to allude to their Sirens as well as the Pierides: [B. Baldini?], Discorso della Geneologia de' gentili, sopra la Mascherata degl'iddei Florence 1565 [i566], p. 35. In the Intermezziof 1589 feathers 'cosi dagli theylikewiseworedifferent-coloured antichipoeti finte'supposedlywithparticularreference to thevictory over the Sirens: [B. de' Rossi], Descrizione e degl'Intermedi..., Florence 1589,p.41. dell'Apparato 27 See T. Puttfarken, 'Bacchus und Hymenaeus: Bemerkungenzu zwei Fresken von Veronese in der Villa Barbaro in Maser', Mitteilungen desKunsthistorischen Institutes inFlorenz, xxIv, 1980, pp. 8-io and fig.5. Here the Muse has in her garland of laurel and flowersa the 'penna piantata sulla cima singlefeather, reflecting della testa' (from the Sirens) whichCartari says is to be seen on some ancientimages (simulachri) oftheMuses in Rome. See Cartari,edn 1556, loc. cit. in n. 26. 28 There might,however,be a pre-Gyraldus example, as Brendan Cassidy pointed out to me, if the famous 'Simonetta' by Botticelliin the Staedel Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt (R. Lightbown, Sandro Botticelli,London 1978,pp. 16-17, no. c3), who wears a cameo ofApollo and Marsyas, could be construedas havinga headdress such as of Siren feathers,rather than just pennacchi nymphshad worn in a 1466 Giostra(cf. A. Warburg, Sandro Botticelli's 'Geburt der Venus' und 'Friihling', Hamburg and Leipzig 1893, p. 43).

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA

introduced it were probably unfamiliarwith its appearance in ancient art.29 In fact Rubens had a specific motive for drawing attention to the featheron his Muse. Two years previously he had designed a titlepage for the edition of the lyric poems of Mathias Casimir Sarbievski (Sarbievius), 'the Polish Horace', published by Moretus at the instigation of the Antwerp Jesuits (P1. 66c).30 Here he had shown Apollo placing his lyre on an altar which bridges a stream at the foot of twin-peaked Parnassus,3' while looking to the Sarbievius's book and Barberini arms several of the individual poems were dedicated to Urban VIII, who was supposedly for the Polish Jesuit a source of inspiration;32perhaps in the face of this combined clerical talent Apollo is dedicating his lyre to go into retirement. Rubens had also shown a Muse, marvelling at the Barberini bees which she evidentlyconnects with those othersbeside her, swarmingover a baby Pindar, the original lyric poet, to drop honey on his lips.33 In his design Rubens ingeniously took up and elaborated on images not only from Sarbievius's own poems,34 but, more particularly, from the

237

panegyricsdevoted to the poet by fellowJesuits, printed at the end of the Antwerp edition;35he therefore probably meant this Muse to be Calliope, who alone is invoked by name in the panegyrics.36 At any rate he represented her with a feather, as in the Bauhuis drawing (P1. 65a). However, on the print by Cornelis Galle the Muse appeared featherless,presumably because the attribute was missed by the engraver (as it has been by most modern scholars).'37This time, with his emphatic note

in librosepicitharisma 35 Ad ... Sarbievii... lyricorum Sarbievius (as in n. 32), pp. 287-336. These repeatedly associate the author (and his ancient model, Horace) with Pindar, Urban VIII, bees, honey (with, for honeyon the example [p. 314], Barberinibees distilling 'Pindaric' poet's lips), Hippocrene, twin-peakedParnassus (sometimes[e.g. p. 301] wettedforthe Muses so can drinkthere),Apollo, Muse(s), thattheApis Urbana lyre and laurel. The poems by E. Puteanus (pp. 289-90), J. Hortensius (pp. 297-98), J. Bollandus (pp. 299-302), M. Mortierus (pp. 305-I i), J. Wallius (pp. 3i1-15), N. Kmicius (pp. 318-27), and J. Libens (PP. 334-36) seem especiallyrelevant.Even details such as the garlands of fruitand flowersseem to reflect and flowers of Puteanus's reference (p. 290) to thefruits the Muses. (Chroicicki drew attention to the verses celebratingSarbievius, but withoutmaking particular comparisons;he was concernedwiththeanalogies with Sarbievius's own treatise on mythology.)That these 29 One instance where the attributemay have been admiringverses should have provided suggestionsfor since Sarbievius's influencedby Roman sculptures,since each Muse has Rubens's title-pageis not surprising, twofeathers on herbrow,is in thedrawingby Frederick poems were evidently beingpublishedin his honour(by Sustrisin Windsor of a Judgment Jesuits). ofMidas, in which the theAntwerp Rubens's Muse Muses are bystanders (L. van Puyvelde, The Dutch 36 Judson and Van de Velde identified Castle, London 1944, p. 64, as Erato; but although she is often called the Lyric Drawings ... at Windsor no. 683 and pl. I). Muse, her normal association with erotic verse (cf. A Gyraldus, De musis[as in n. 7], p. 107; Wegner [as in Paul Rubens. ofPeter 30 SeeJ. S. Held, TheOil Sketches Princeton1980,pp. 418-19, no. 304; xx, n. 7], p. 97) makes her less suited to the poems of the Critical Catalogue, pl. 304;Judson-Van de Velde, I, pp. 265-68, nos 62 and Jesuit author. Held pointed out that Calliope is 62a; II, figs 212-13; and J.A. Chroicicki, 'Rubens w mentionedin one oftheJesuitpoems (Sarbievius [as in Historii pp. 185-97. The n. 32], p. 334: in the poem by Libens); for the other Polsce', xII, 1981I, Sztuki, Rocznik thebook is in fact a see p. 302. This latter reference to thePope, is signedby the reference dedicating preface, quotation by Bollandus of a line by Sarbievius himself, AntwerpSocietyofJesus. shape ofthe mountainindicatesthat who indeed invokesCalliope several times(Lyrica, I, Io, 3a' The distinctive it is biceps Parnassus, ratherthan Helicon, as is always 8 [p. 19]; n, 20, I6 [p. 76]; Iv, 9, 36 [P. I59]). But assumed, even if the streammay still (in this allegory) whetheror not we call her Calliope, she is probably be Hippocrene; Ovid, Metamorphoses, II, 221I (cited in intended,like the Muse forBauhuis (P1. 65a), to stand connection with Helicon in Judson-Van de Velde, forPoetryin general. to Parnassus. p. 267) actually refers 37 Only Julius Held drew attentionto it (loc. cit. in 32 Writing in this edition (M.C. Sarbievius, Lyrica, n. 30), referring to the Bauhuis title-page. For the Antwerp 1632, p. 299) J. Bollandus, forexample, calls engravedtitle-pageby Galle see Judson-Van de Velde, him 'pontificae fig.212. Galle also seems to have given Apollo's lyre poesios imitatorem'. xx, had 6 strings and 33 Pindar was recognizedboth byJudson and Van de an extrastring;no ancientinstrument Velde and by Held (cf. n. 3o), and they provide the Rubens's had 5 in thesketch.The ancientlyre(invented a tortoiseshell different sources forthis legend. For the association of from by Mercury,who gave it to Apollo) the Muse(s) withbees see also Gyraldus,De musis but in its primitive (as in is usually said to have 7 or 9 strings, state it is sometimesgivenonly 3 (cf. above, n. Io), and n. 7), P. 13. 34Some analogies are drawn by Held, in Judson-Van several authoritiestalk of 5 strings(cf. Vigenbre [as in n. 1o], pp. 76-89, esp. pp. 87, 88). de Velde and esp. byChroicicki (as in n. 30).

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

238

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS

collection of Fulvio Orsini, one of Menander and Sophocles (forcomedy and tragedy)as well as the Herodotus and Thucydides already mentioned.41 Already beforethe Bauhuis titleRubens had experimented with designs using double busts based on ancient prototypes. Three related drawings of c. 1617-18, done for some decorative use and probably for someone (or three people) in Rubens's close circle - the inscriptions indicate they are to be made of ebony, ivory and (for the helmet of one pair) perhaps also iron or amber - show Rubens relating them to what he calls a Hermathena (P1. 67b--d).42 One illustrates a Silenus and a satyr (P1. 67b) - a satyr of course of the

(P1. 65a), Rubens was making sure therewould be no mistake. In the Sarbievius title-page (P1. 66c) the featherwas of course not strictly necessary in order to distinguish Apollo from the Muse, since, although theyboth wear laurel crowns,one is obviously female;forthe Bauhuis design which consists only of a double bust some attribute on the head was essential to characterise the figurewith Minerva as a Muse ratherthan Apollo Citharoedus.38 Rubens calls his double bust a variation on a and refers to precedentsforthis. It is Hermathena evident that the basic formal model was provided by those ancient double herms which represent two persons (usually writers or philosophers) or two deities who are somehow related to one another.39Several examples were known in the Renaissance, and among those published in the later sixteenth century are a Herodotus and Thucydides, an old Dionysus with a satyr (P1. 67a), and a Zeus Ammon and Dionysus (apparently interpretedas a Ptolemy and his wife).40 As a young man Rubens had in fact copied two double portrait herms in the

ut portraitherm); Achilles Statius, Illustrium viro[rum] exstant Rome (Lafrery) 1569, pl. L in urbe vultus, expressi (Dionysus and Satyr; cf. plS LI-LII); E. Spanhemius, edn Dissertationes de praestantiaet usu numismatum, Amsterdam1671, pp. 362-64 (forthe 'Ptolemyand his wife'). Pirro Ligorio also illustrateda double herm of Sappho and anothershowingSocratesand Phaedrus (in The one case witha 'grasshopper' [i.e. locust] on Socrates's for Rubens's design decorating 38One oftheherms Education fromhis Achilles series of c. 1630 head: cf. Plato, Phaedrus,259) (E. Mandowsky and of Achilles RomanAntiquities, Studies of appears to show a Muse (with lyre,withoutfeather) C. Mitchell, PirroLigorio's providedby Chiron; the Warburg InstitutexxvmI,London 1963, pp. 87-88 alluding to themusical instruction as she does not have a laurel wreathshe is in thiscase [no. 71], 95-96 [no. 82]; pls 41a, 50c). And Heemskerck from Apollo. But at least one print copied anotherofa youngand old Dionysus (C. Hiilsen (just) distinguishable Marten van von after her femininity the design clarified Skizzenbiicher by representing and H. Egger,Die Riimischen Berlin 1913,I, p. 22, fol.4Ir; n, pl. 42; cf.also her with breasts. See E. Haverkamp Begemann, The Heemskerck, AchillesSeries. CorpusRubenianum X, fol.47r, pl. 48). Ludwig Burchard, London 1975, P. 99 and n. 5 and pls 13-18. Once again 41These copies belong to a series done not afterthe is unclear.She mightbe Calliope, to originalsbut after herpreciseidentity drawingsby Theodore Galle; and not whomAchilles is said to have sacrificed(cf. Held [as in all are veryconvincingas worksof Rubens, even if the are in Rubens's hand: theymusthave been n. 30], I, p. 175); but she could this time be Erato, not inscriptions veryearly,beforeI6oo, or else withthehelp onlybecause ofthegarlandsofrosesabove, but because made either this Muse fitsonly too well with the eroticratherthan of assistants, with the retouchingsin pen added by heroictoneofRubens's versionofthelifeofAchilles. Rubens. The Menander andSophocles (inscribed'Menan39Judson-Van de Velde, I, p. 271 referto one such der') is one of the most powerful.See H. M. Van der double-herm:that of a satyr and satyressin Pompeii. Meulen-Schregardus,PetrusPaulus RubensAntiquarius, For a selection of examples of other combinationssee Alphen aan den Rijn 1975, pp. 64-70, I76 (c.7), 179 A. S6rullaz,Rubens, Altertumswissender classischen (c. I2) 182 (c. I7) and pls Paulys Real-Encyclopiidie xxlI-xxlI; cat. exh. du musie du Louvre, ses e'lves.Dessins Neue Bearbeitung, eds G.Wissowa and W. Krol, ses maz^tres, schaft. Paris 1978,pp. 53-58, nos 44, 47, 48 (and figs). Stuttgart I894-1972, vIII, I, cols 696-708 (s.v. Hennrmai), 42 See A. M. Hind, Catalogue byDutchand ofDrawings esp. 704-08; also P. Paris in C. Daremberg and in theDepartment et romaines, FlemishArtists des antiquitis E. Saglio, Dictionnaire of Printsand preserved grecques in the British Museum, London 1923, PP. 23Paris 1875-191I7, pp. 132-33, s.v. Hermae, Hermulae; Drawings x1, II, Dissertationen 24, nos 55-57; G. Gliick and F.M. Haberditzl, Die A. Giumlia, Die neuattischen Doppelhennrmen, Berlin 1928, pp. vonPeterPaul Rubens, Wien 161, Vienna 1983; H. Wrede, Die Handzeichnungen der Universittit Trierer Beitrage zur Altertumskunde, Antike Herme, I, 38-39, nos 81-83; J. Rowlands, RubensDrawingsand cat. exh., London 1977, pp. 89-90, nos 98, 99, Mainz 1985,pp. 17-31, passim and pp. 52-53. Sketches, 40 See [F. Orsini], Imagines ex ioi. The drawings have been dated c. 1i615,but the illustrium etelogiavirorum a child ofRubens's son Albertsurelyrepresents Rome (Lafrery) 1570, pp. 86-89 portrait Fulvi Ursini, Bibliotheca cf. p. 76 foranother double- at least 3 or 4 yearsold. and Thucydides; (Herodotus

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA Renaissancetype (that is, an ancientPan).43 Another has Cupid and Psycheback to back, withRubens'snotethattheCupid 'is modelled on mylittle hiseldestson,bornin 1614 Albert', would surely have (P1.67c)44- and theartist been pleased to knowthattheancientRomans also used children for doubleherms, at anyrate in the combinationof boy paniskos and girl

239

Silenus bust which rather resembles this see W. Amelung, Die Skulpturen des Vaticanischen Museums, Berlin I903-08, 1,pp. 461-62, no. 229 and pl. 47. There are also exampleswhichcombinea satyr(oftheclassical type,beardless and withpointedears) withSilenus (cf. G. Lippold, Die Skulpturen desVaticanischen Museums, III, 2, Berlin 1936, no. 34 and pl. 206; also Wrede, 471, P. Herme [as in n. 391,PP. 29-3o). But thereis no evidence thatexamples such as thesewereknownto Rubens. 44 Its inscriptions are: 'Cupido ex Albertuli mei Imagine' and 'Psyche'. von 45 See H. Wrede, Die Spiitantike Hermengalerie Berlin 1972, pp. I21-23, pls 65 (4) -69 (i); Welshbillig, also idem, Herme (as in n. 39), p. 27. But I have foundno indicationthathermsofthistypehad been discoveredin Rubens's time. 46 It is inscribed at the top 'HermAthene'; on the helmetis written 'Ex ferro aut ebeno' and below 'aut ex in electro';thefacesare to be 'ex ebore'. The inscription the lower right: 'Memnoni nigram Ex altr[..] Auror[..]' must referto a lost drawing which was to show a paired Memnon and (his mother)Aurora (to be made ofebonyand ivory?). 47 See Stuart Jones (as in n. 14), p. 141, Sala delle Colombe no. I2; pl. 34. Both figures have roundhelmets with broken crests; that of Hermes had wings and Athena had an aegis. Stuart Jones refersto Cicero's description;forwhich see below. See also Bottari and Foggini (as in n. i5), I, pp. x6-x7, 73 and pl. vi of introductory plates at theend; Visconti (as in n. I i), iu, p. 48 n. and vii, p. Iox.

whathe meant. He was immediately recognized a solutionto a problem actually presenting which had exercisedboth antiquariansand of the period- a solutionwhich philologists would be introducedto the scholarlypublic when (in only in the mid-eighteenth century to the ignorance of Rubens's contribution the idea in debate) G. G. Bottarirediscovered maenad (or paniske).45 Rubens's thirddrawing, thelight oftheCapitolinebust.48 The term hermathena and theevidence for the however (P1.67d), is the one that is a real i.e. a conjunction of Mercury and existenceof a class of sculptedobject of this Hermathena, has labelleditas such.46 name in antiquity and theartist Minerva, dependson twopassages in An ancient double bust of Mercury and Cicero's letters to Atticus.49 in Cicero'sfriend, Minerva (or Hermes and Athena) is in fact responseto the orator'srequestforsome art extantin the CapitolineMuseum,and it was, objectsto decoratehisgymnasium (the place he on its discovery, hailed as a Hermathena.47 But used as a study)had senthim from Athensa no exampleof thistypeappears to have been statue which combines in it Hermes and in thetime known ofRubens. Andinidentifying Minerva.Cicerois very pleasedwiththewayit the ancientdouble-herm overthewholeroom;so thetwo typewith the word seemstopreside hermathena theartist was notrelaying a standard deitiesare, he feels, to his onlytoo appropriate (as scholarsseems to have assumed in 'academy',forHermesis suitedto all gymnasia theory their discussions ofRubens'sdesign),although and Minervain particular to his own.s51 In fact Moretusand otherlearnedfriends wouldhave as patron of eloquence Mercury was as suitedto thegreatorator's specifically studyas was the goddess of wisdom - and it was with this in mind that Rubens undoubtedly used and Minervato characterize the Mercury 43It bears the inscriptions: 'Silenus', 'Satirus' and for F. de 'posset unus ex ebore alte[r] ...'. For an ancientdouble good ambassador in his title-page

4s Bottari's catalogue was firstpublished as Museum ... cumanimadversionibus Capitolinum ..., 3 vols, Rome see I, pp. 5-6 and pl. vi (facingp. 18). 175o-55: 49Cicero,AdAtticum, I, 4, 3; I, 1,5. Cf. I, 6, 2; I, 8, 2; I, 9, 2; I, Io, 3 (in chronologicalorder) forthe context.See J.J. Pollitt,TheArtofRomec.753 B.C.-337 A.D. Sources andDocuments, Englewood Cliffs N.J. 1966,pp. 76-78 for a translation. 50so AdAtticum, I, I, 5: 'Hermathena tua valde me delectat et posita ita belle est ut totumgymnasiumeius anathema esse videatur...' (literally,'... it is so well placed that thewholegymnasium seems to be a votiveoffering [to it?] ...'). However,Janus Gruter'seditionofCicero (Opera, Hamburg 1618-19), which Rubens had acquired by 1624 (cf. M. Rooses, 'P.P. Rubens en Balthasar Moretus (I), IV', Rubens-Bulletijn, ii, p. 198) has the to thesun' [cf.in, reading'qhouto ('an offering dtvOa' p. 146 and p. 36o]), which, as later commentators observed,makes littlesense. s5 Ad Atticum, I, 4, 3: 'Est ornamentum Academiae propriummeae, quod et Hermes commune omniumet Minerva singulareest insigneeius gymnasii.'

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

is explained by Renaissance mythographers Hermathena as a conjunction of wisdom and eloquence: see, e.g., Cartari (edn 1556, as in n. 26), fols68v-69'. As patrons of artists as well as diplomats the two gods adorned Rubens's own house. Cf. D.J. Gordon, 'Rubens and the ed. Whitehall Ceiling', The RenaissanceImagination, S. Orgel, Berkeleyand London I975, PP. 45-49; and on Rubens's J. Muller, 'The Perseusand Andromeda xii, 1981-82,pp. I41-43 and figsI2-I 3. house', Simiolus, to be associated withthehermsforthe s3 It is evidently mentionedin I, 8, 2 and I, 9, 2, and with the gymnasium mentionedin I, o, 3. On themeaningofthe HFlermerakles word herm see the entrieson Hermaicited in n. 39; a good account available to Rubens - he boughtthebook in August 1623: Rooses (as in n. 50), p. 196- appears in ... inadventum PublicaeGratulationis J. Bochius, Descriptio Ernesti, Antwerp 1595, p. 69, pointingout that Greek ofMercury,human to the hermswere originally figures navel and square bases below,but thatthewordcame to be used forbustson such bases, and ofotherpeople and (as in n. g) gods. Cf. also Gyraldus, De deis gentium pp. 416-I 7; Orsini (as in n. 40), pp. 6-7. vI, 23, 1-3, Cicero also provides 54 In hisAd Familiares, an amusing discussion of which statues of gods might roomsand situations. suitdifferent ss I am hereconcernedonlywithattemptsto represent not with what Cicero actually meant by a Hermathena, of Mercuryand the many Renaissance representations whetheras patronsof art, learning, Minerva together, diplomacy or all three (cf. above, n. 52). These latter images are of course oftenconnected,at least in some attenuated way, with Cicero's discussion of the but are not themselves,strictly Hermathena, speaking, For such images see Gordon and Muller Hermathenae. (loc. cit. in n. 52), T. DaCosta Kaufmann, 'The Eloquent Artist: Towards an Understanding of the Stylisticsof Painting at the Court of RudolfII', Leids Kunsthistorisch I, I982, pp. I 9-48, esp. p. 125, Jaarboek, as well as T. Gerszi, 'Die Humanistischen Allegorien interder RudolfinischenMeister', Actesdu 22e congres del'art,Budapest 1972,PP. 755-62. national del'histoire

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS with the Marselaer'sLegatus.52Fromwhat Cicero says Achille Bocchi took the Hermathena ofhis as theemblem domantur Sic monstra elsewhere itseemsclearthatthestatuetookthe motto itas a herm form of it herm, that is, it ended in a Bologneseacademyand illustrated and another ofMinervaunited bya quadragonal base, thoughnot necessarilya ofMercury of the combined the who, through power Cupid, full-length one.53 of his gods,controls Cicero's discussionof the decoration in the the'monsters' represented to room was familiarto Renaissance scholars; lion'shead beneath him(P1.68a). According of a contemporary sanctisaccountthissymbolized indeed,in its not too seriousconsideration as taught themesand gods to the sima byBocchi,for philology Philologia decorum,in fitting a is a study involving both eloquence and function of the place, it musthave provided nice modelforRenaissanceiconographic pro- wisdom,which,when guided by divinelove, and artists, leads throughthe conquest of base sensual And severalhumanists grammes.54 and its appetitesto the attainment in particular of truefelicity.56 intrigued bytheHermathena Bocchia'was meanttoserve symbolism, attempted reconstructions.ssThis 'Hermathena as the printer's mark,and perhapsalso to be represented on the outside wall of the AccademiaBocchiana (cf. P1.68b), whichhas the motifof the lion's head repeated in its 52 See Judson-Van de Velde, I, pp. 344-48, no. 84; II, to But theimageowesitsdiffusion decoration.57 forRubens's explanation. The pl. 286 and pp.

240

50o-I 56 See G. Sambigucius, In Hermathenam Bocchiam Bologna 1556, esp. pp. 20, 26, 32-35. The interpretatio, emblem as illustratedin Bocchi's own book (cf. below, n. 58) is reproduced on pp. 22-23. Sambigucius does not, however, seem to be aware of the original he simply talks (pp. 34-35) of Ciceronian Hennrmathena; how Bocchi, 'imitatingthe ancient poets', showed the '... Minervam ... atque Mercurgodsjoined together: ium fratrem, veterespoetas imitatus,nosterBocchius simul connexosdepinxit,quos uno nomineconiunctum vocat'. graece propriissime EQga8ivlyV 7 On the Palazzo Bocchi and its decoration see J. K. Schmidt, 'Zu Vignolas Palazzo Bocchi in Bologna', in Florenz, Institutes des Kunsthistorischen Mitteilungen xii, 1967-68, pp. 83-94; A.M. Orazi, Jacopo Barozzi da di un architetto Bolognese, 1528-1550. Apprendistato Vignola Rome 1982,pp. 229-70. A printof i545 (Schmidt,pl. I; Orazi, fig.352) indicates that the originalidea forthe decorationwas to have thebuildingcrownedbya statue of Mercuryand of Minerva at eitherend of the facade. In the event there were no such statues, and the illustrationfrom the Symbolicae Quaestiones (edn 1555, on the side of the p. 230) which shows a Hermathena palace (Pl. 68b) may be merelysymbolic(to characterize the building as the academy). But the present buildingdoes have a lion's head withringat the top of the rusticationon one corner. Cf. Orazi, pp. 234-35; Schmidt,pp. 9I-92. On the academy and its emblem see also M. Maylender, Storia delle accademie d'Italia, Bologna 1926-30, I, pp. 452-54; as for the printer's a Bologna, dellastampa Bologna mark,A. Sorbelli (Storia 1929, pp. 105-06) talks of books fromthe academy's di delleaccademie press, and M. Fanti (Notiziee insegne Bologna..., Bologna I983, pp. 44-45) reproduces an image which looks like a printer'smark; but, as Orazi and Rotond6 pointout, no-onehas yetcitedan example ofa book withthisdevice. Cf. Orazi, p. 259; A. Rotond6, in Dizionario biografico degliItaliani,Rome I969, xI, p. 69 Achille). (s.v. Bocchi,

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA

241

Vignau-Schuurman, Werke Hoefnagels, Leyden 1969, p. 78. Wind gives Joris u, otherinstancesofCicero's Hermathena (or Mercuryand oftheperiod with Minerva) being associated by writers academies or schools; as does Kaufmann (loc. cit. in 62 See C. Robertson, The Artistic Patronage of Cardinal n. 55), citingLomazzo's recommendation ofthesubject Alessandro Farnese (1520-89), Ph.D. thesis, Warburg forsuch contexts(Lomazzo [as in n. 23], II, p. 303). ofLondon, 1986,I, pp. 121-22. For Institute, University et an excellentcolour reproduction s See J. Bochius, Historica Narratio Profectionis see I. Faldi, II Palazzo Serenissimorum et Farnese Alberti di Caprarola, Inaugurationis BelgiiPrincipum edn Seat, Turin 198 I, pp. 23&-37. It Isabellae... , Antwerp I602, p. 248 and pl. p. 263. Cf. is interesting thatCaro seems tohave been well disposed to Bocchi and his academy; cf.Maylender (as in n. 57), Wilberg (as in n. 58), u, p. 78. 60 Bocchi (edn 1574, as in n. 58), pp. ccxxx-ccxxxi, pp. 452-53. no. cix: the emblem is entitled 'Mlb6 666povnotLvY 63 See Gyraldus, De deis gentium (as in n. 9), p. 417; dvEtiLEOTOVXataLXtEtv' ('Ne linque aedificansdomum Cartari (edn 1556, as in n. 26, fol.69r) says that the impolitam'). On Alessandro's patronage of the Romans joined statues of both gods to make one. For Accademia Bocchiana afterthe death of Paul III see othersimilaraccounts see below, n. 74. Schmidt(as in n. 57),PP. 9I-92 and Orazi, ibid., p. 259. 64 On thismotif see Wind (as in n. 58), pp. 98-99, 107, lente idea was not mentioned Cf. Sambigucius (as in n. 56), p. 14, where,however,he 203, 215, thoughthefestina seems to despair of Alessandro's ever having the time by Bocchi as Wind implies (p. 203). The association of and resourcesto help finish the building. the tortoise with Mercury in connection with the 61 Bocchi (edn 1574, as in n. 58), pp. ccxxxii-ccxxxiii, inventionof the lyre (cf above, nn. 10, 37) seems here no. cx. The motto here is: 'Est nulla vita lautior irrelevant. domestica, nec laetior'. The tortoise is utteringthe 65 See Schmidt (as in n. 57), P. 9I; Orazi (ibid.), proverbial'orxogglkog orxog LtoLrog' ('home is sweet, pp. 234-35. It may not have been completedeven when home is best'). Bocchi died in 1562.

its inclusion in Bocchi's famous Symbolicae begun in 1556 by the architectof the Bolognese firstpublished in I555.5s8 Certainly academy, Vignola, the room intended as a Quaestiones, it seems to have been taken for the authentic study should have included a painted HerCiceronian Hermathena (P1. 69a). This time,however,it is not a by the designers of the mathena question ofa 'marriage' by Cupid oftwo herms. pageantry for the entryof Albert and Isabella intoAntwerpin 1599, when it was copied forthe The central picture of the Stanza dell'Erarch celebrating Mercury and Minerva as twin matena, painted by Federico Zuccari some time patrons of Antwerp's trade.59 In fact the after 1566 and probably on the advice of the Hermathena had been included twice in Bocchi's Farnese 'iconographer' Annibale Caro,62 shows book, once in an emblem dedicated to the union of Mercury and Minerva quite Stephanus Saulius (P1.68a) and again in literally.The gods simply share one pair of legs another in which the author begs Alessandro and the details of theirimprobable conjunction hidden by drapery. Bocchi's herms Farnese to help him finish building the are tactfully academy (P1.68b).60 This message was then are thus ignored to allow for one figuremade reinforced in the 'symbolum' immediately out of the two gods - and, after all, the following, also directed at Alessandro; this mythographic handbooks talked of 'a statue illustratedAesop's storyof the tortoisewho was formed of Mercury and Minerva'.63 But forcedbyJupiterto carryhis house around with Bocchi's tortoise intriguingly remains. Now him permanently,afterhe had been reluctantto restingunder the single winged footofMercury, leave home to attend a wedding feast (P1. 68c); it suggests a pun on the familiarfestinalente Bocchi asks his patron for the means to motifso oftenused in emblems and devices,64 complete his own house so that he may be able - and perhaps also that the building ofhouses, to come to the 'wedding of the good Her- even those for Mercury and Minerva, makes mathena'.61 It is hardly surprisingthen that in haste only slowly (Bocchi's academy was still Alessandro Farnese's new palace at Caprarola, unfinished in I560).65 Still, as the proverbial home-loving creature, the tortoise would also have reassured the Farnese that this painted Hermathena was happily settled in their household. 58 A. Bocchi, Symbolicae edn Bologna I574, Quaestiones, The Caprarola double-god was proudly pp. ccxvi-ccxvii,no. cii. Here Bocchi has added as his motto: 'Sapientiam modestia, progressioeloquentiam, labelled +HPMAOHNA, and its designer may felicitatem haec perficit'. Cf. E. Wind, Pagan Mysteries in well have thought that the fact that it was the Renaissance,edn Harmondsworth 1967, p. 203; seated, and thereforestable, made up for the Gordon (as in n. 52), PP. 48-49; also T. A. G. Wilberg absence of any herm, a featureclearly implied Die Emblematischen Elementeim

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

242

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS

simply a herm with Athena on top (P1. 70a).69 mentioned by Similarly the related Hermerakles which are found Cicero, as well as theHermerotes in Pliny,7?would be interpretedas herms with these deities, as Lorenzo Pignoria points out in his edition of Cartari's Imagini, reproducing next to an image derived from the Hadrianic coin another of an ancient herm of Hercules.71 was taken over by the Orsini's Hermathena with the Milanese Accademiadegli Ermatenaici, motto 'AM'OIN ?ENEKA ('for the sake of both [gods]') and is illustratedforexample in a printforthe decoration of a thesis published in 1624 (P1. 70b).72 It is indeed accepted as the correct interpretation by some modern archaeologists.'3 However Pignoria added that he is not sure if the Hermeraclesand the Hermathena were not ratherimages of these gods embracing. Presumably he considered that the

in the print by by Cicero. The Hermathena Aegidius Sadeler after Hans van Aachen was also labelled, this time in Latin (P1. 69b), and also tried to improve on Bocchi. Joris Hoefnagel, credited as the 'auctor' of the design, borrowed Bocchi's inscription 'Me duce perficies. Tu modo progredere' ('under my guidance you will succeed; only go forward'),66 but, perhaps simply because these words seem to require a guide that can walk, he made his pair of gods obviously mobile. The result is a lively duo, with Mercury and Minerva each to express a leg over the other in an effort lifting conjunction, but all the time remaining on a square base which may be a substituteforthe 'herm'. But even if this solution was ideally suited to the 'mannerist' art of Rudolfine Prague it was hardly likely to satisfy any archaeologists as a reconstruction based on Cicero.67 They had generally taken another, much simpler line, consideringthe problematic texts in relation to surviving images from antiquity. On the basis of a coin of Hadrian, which seems to have been introduced into the discussion by Aldo Manuzio,68 and which arguably shows a figureof Minerva as a herm (although no-one could relate this to the inscriptionon the obverse of the coin), Fulvio Orsini suggested that the Hermathenawas

66 See Wilberg (as in n. 58), I, pp. 195-98, pp. 77-78 n11, and fig.I20, pointingout the source of the inscription. Only one word was changed: 'pervenies' for'perficies'. Wilberg observes that the print,which bears the title and Cursus is the2nd in a setof3 (theothersbeing Occasio is a guide forlife,showing the Hermathena Praemium): how to help byartwhatfallsout badly bychance; itis an in adversis and a refugium ornamentum in prosperis (cf. the mottosoftheputtiin eithercornerat the top). 67 For a considerationof this print in the contextof Rudolfine imagery see Gerszi (loc. cit. in n. 55), PP. 758-59 and pl. 248, 5; also Muller (loc. cit. in n. 52), and by Hoefnagel fig.17. Wilbergalso discusses a miniature Ortelius (as in n. 58, I, p. 195 and ii, made forhis friend fig.I19). This shows at thecentrean owl withcaduceus (standingforMinerva and Mercury) on top of a globe and book, and, although it has the inscription 'Hermathene' beneath, is meant as an emblematic of allusion to Cicero's statue ratherthan an illustration

I have not,however, on Cicero's letters. his commentary found a referenceto the coin either in the edition of Cicero's letters by Aldo Manuzio theElder (I consulted ofselectedletters edn Venice 1513) or in the translation publishedby Manuzio theYounger.

it. 68 Accordingto Pignoria (cf. below, n. 71), thiswas in

69 Orsini (as in n. 40), p. 85; also p. 7; cf. J. Spon, edn Lyons 1683, pp. 98Recherches curieuses d'Antiquiti, 123, esp. p. III, criticizing Orsini's reading of the inscription. 70Historia Naturalis, xxxvI, 5. 71 V. Cartari,Le vere ed. e nove dei deidegli antichi, imagini L. Pignoria,Padua 1615, PP. 318-20; and note, p. 551. This herm of Hercules had in fact been illustratedby Orsini (Imagines [as in n. 40], pp. 6o-6I; cf.Mandowsky and Mitchell, [as in n. 40], pp. 83-84, no. 61 and pl. 33: copied fromPirro Ligorio, and largelya Renaissance restoration) and discussed by him as a Hercules to Hermeracles. withoutreference Prodicius, However, it as thelatterin thelightof was subsequentlyinterpreted his views on the Hermathena. Cf. J. Gutherius in J. G. Utrecht Graevius, Thesaurus Antiquitatum romanarumn, withreference col. 1240 on theHermeracles, 1694-99,xnII, to Orsini. On herms of Hercules called Hermeracles cf. Bottariand Foggini (as in n. 15), I, pp. 13-14 and pl. I of introductory plates at theend; Visconti (as in n. I I), vI, pp. 88-92 and pl. xIii. Visconti also discusses double busts ofHercules and Mercury,thoughhe does notcall For thesecf.Giumlia (as in thesestatues ofHermeracles. n. 39), PP. 154-56; and for herms of both types see (as in n. 39), PP. 2o-21. Wrede,Herme 72 See E. Schillingand A. Blunt, The German Drawings tothe Castle... andSupplements of Catalogues ... at Windsor Italianand French Drawings..., London and New York [1973], p. 136, sub no. 644 and p. 148, fig.48. The print is inscribed 'Bartholomaeus Cremonensis delin.' and 'Cesar Bastanus sculpsit Mini 1624'. I am indebted to toit. For the drawingmyattention Jennifer Montagu for academy and its device, see Maylender (as in n. 57), II, pp. 300oo-02. (as in 73 See above, n. 39; also Wrede, Hermengalerie n.45), P. 128.

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RUBENS'S MUSA THENA theoryof the hermof Athena fails to satisfy Cicero's apparently ofthetwo equal treatment too in the way thatso many deities,reflected commentators talkofstatuesofthetwodeities and Rubens must have joined together;74 agreed.75 as illustrated Rubens'ssolution, in however, thedrawing labelledHermathene (P1.67d), does in Ciceroand to justicebothto thedescription the evidenceof a distinct visual tradition (for It may be that herms)in ancientsculpture.'76 theartist's; theidea was not entirely certainly he must have been influenced by discussions with antiquariansin his circle. Rubens's old Woverius friendJoannes (Janvan de Wouver), who had studiedunder JustusLipsiuswiththe artist's ofthe brother, Philip,and is thefourth in the in thefamouspainting FourPhilosophers Palazzo Pitti,musthave been somehowinvolved. He actually adopted a Hermathena very similarto thatin thedrawing, withthemotto

243

ed. Tozzi, Padua I621, 74 See A. Alciati, Emblemata, in Graevius veterum, p. 53; J. P. Tomasinus, De donariis (as in n. 71), xII, col. 387; G. Figrelius, De statuis illustrium edn Stockholm I656, pp. 2I0-II; romanorum, also above, n. 63. proposed 7 Anothersolutionwhich was, I think,first too late for Rubens, gained some by Spon, therefore acceptance among antiquarians and was publicized by Montfaucon,even if it is surely the worst of all these For here proposals in matchingCicero's specifications. theHermathena, as well as theHermeros and Hermerakles, is interpreted(by analogy with figures who bear the emblemsofotherfigures on ancientgems) as a Mercury withthe attributes of Minerva (or Eros or Hercules) or vice versa. (See Spon [as in n.691, pp. 98-123; Montfaucon [as in n. 9], I, pp. 82-83 and pl. 39.) This solutionactuallyignoresbothoftheelementsprescribed in the lettersto Atticus: it is neitheran image of both ofa herm. gods, noris it in theform 76 The view that the Hermathena were and Hermeracles double herm busts is now widespread; although most scholars suggest that they might equally have been - and herms with Athene or Herakles respectively perhaps sometimesone, sometimesthe other. See the works cited in n. 39; also Pauly-Wissowa (as in n. 39), s.v. Hermathene und Hermerakles. As regards Cicero's evidence,theonlypointagainst Rubens's interpretation seems to me thatin thiscase Cicero mighthave talkedof Minerva and Mercury (rather than Minerva and Hermes).

is I629 (P1.7od).77In thiscase theHermathena more obviouslypart of a herm, and, since Minerva wears a high crestedhelmet,Merhas beenextended at thetop,and cury's petasus its wing has been made to join up with Minerva's crest.In facta printattributed to Cornelis Galle (P1.70e),78 thefunction ofwhich has never been explained, reproduces the Woveriusimage with a completedherm,to in theway thedouble herms do appear exactly in Achilles Statius's book and in late sixteenth-century prints (cf. P1. 67a). This, evenhave been an illustration therefore, might to a projected 'reconstruction' of Cicero's Hermathena whichsomeonein Rubens's circle (perhaps Woverius, perhaps even Rubens intended to publish.But no traceof himself)79 thetheory seemsto have found itsway intothe literature oftheperiod;and ifRubens scholarly mustsurely have communicated his idea to his Peiresc,withwhomhe discuscorrespondent, Honesti Comes Ratio ('Reason is the companion of sed so manyproblems ofancienticonography, virtue') in a medal which has been dated to the only thing that might be construedas 'evidence'of thisis the (otherwise surprising) factthata medal, dated 1625,ofJean Talon, advocategeneraloftheKing in theparlement de has on itsreverse, a inscribed Paris, Hermathena, and Minervaback to pair ofbustsofMercury back on a quadragonal base.so In fact the

desXVII provinces 7 See G. van Loon, Histoire metallique des Pays-Bas, The Hague I732, II, ii, pp. 209-10, illustratingtwo versions of the medal with different inscriptions(spellinghis name 'Waverius') on the obverse,both by A. Waterloos. An example ofone is in the British Museum (Dutch and Flemish, Large, 8, I629-37 [196]). For the dating of the medals see A. Pinchart,'AdrienWaterloos',Revue dela numismatique Belge,2nd ser.,v, 1855, PP. 253-54; in both Woveriusis called 'eques', a titlehe receivedonlyat thisdate. desestampes 78 C. G. VoorhelmSchneevooght,Catalogue P. P. Rubens, Haarlem 1873, p. 148,no. 94; gravies d'aprks cf.M. Rooses, L'Oeuvre deP. P. Rubens., v, Antwerp1892, p. 188,sub no. 1364. 79 Possiblyin theabandoned projectforthe 'gem book' (including other antiquities) for which Rubens prepared severalplates whichwere neverused. On thissee Van der Meulen (as in n. 41), pp. 36-72. so For this medal see F. Mazerolle, Les midailleurs Paris 1902-04,II, p. 18o,no. 883. It is illustrated franCais, in Trisor denumismatique etdeglyptique. Midaillesfrancaises le rigne de Charles VIII jusqu'a celui deLouisXVI, eds depuis P. Delaroche, [L.P.] Henriquel-Dupont and C. Lenormant,I, Paris 1836, pl. LvII, no. 5; cf.p. 48, no. 5. This involvesthe idea ofthe Hermathena being twinbusts but does not actually resemble (as Rubens's does: cf

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

244

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS

absence of antiquarian discussion of the theory But in his note to Moretus (P1. 65a) Rubens is itselfanother indication that Rubens was the was especially proud of his 'fabrication' not author of the idea; as a painter's argument it because it resolved the question of the Herneed never have been presented in words, but mathena, but because it adapted the form to a drawing of new pairing appropriate to Bauhuis's book: the simply depicted, in the Hermathena c. 1618 (P1. 67d). This drawing would thenhave Muse and Minerva.83 And in this he was been adapted for both the Woverius medal undoubtedly inspired by the conceit already (P1. 7od) and the Galle print (P1. 70e), quite used by another learned Jesuit and friendof probably by the artisthimself.If Rubens indeed Moretus and Rubens, Erycius Puteanus. In designed these adaptations he may have felt 1602 Puteanus had published his Musathena, sive dissatisfiedwith the shape theygive Mercury's Notarum Heptas.84In thisbook the author argues hat, unclassically high to match Minerva's that he has invented this 'novum nomen, helmet. At any rate in a sketchof c. 1630-31 for novum numen' since he prefersthe Muse to the printer's mark of Joannes Meursius he Mercury (referring to the Hermathenaand produced a modified version of his Hermathena Cicero in passing) because she is associated which avoids the headgear problem (P1. 70c). with the highest things (the Muses being in Here the paired busts of Mercury and Minerva charge of the spheres), and her conjunction are back to back but separated by their with Minerva, will, as it were, divest that attributesand a hen incubatingher eggs- with goddess of her traditional associations with Minerva's owl (night) and Mercury's cock war.85 Rubens, who probably owned this book (day) this makes a neat rebusfor Meursius's (his brotherPhilip had contributeda laudatory mottoNoctuincubando diuque('by brooding night poem to introduceit),86must have thoughtthat and day'); in this arrangement the (parted) these same associations were equally suited to gods can wear their conventionally different- the high-minded Bauhuis.87 Unlike Puteanus sized hats.81And whetheror not he himselfhad formulated it, the 'Woverius' version of the Hermathena was later associated with Rubens heads somewhatsquashed together, forC. Galle's titleemblematically: not, as on his friend'smedal, to page to C. Curtius, Virorum exordine Eremitarum illustrium symbolize a combination of reason with prob- D. Augustini Elogia (Antwerp, Cnobbaert, 1636) (cf. ity, but to invoke Mercury and Minerva as Judson-Van de Velde, I, p.68 and n, pl. 23), which patrons of artists, when it accompanied the perhaps supports the idea that the anonymous print portraits of Rubens and Van Dyck in a print (P1. 70e) is indeed by Galle. observed that afterErasmus Quellinus honouring Antwerp's 83 Held (loc. cit. in n. 6 above) rightly oftheMuse Rubens's satisfaction lay in thesubstitution twinluminaries of painting.82 for as Evers's idea that it came from

Mercury, against his employing thesame profile forboth. 84 It is ofcourse likelythat Puteanus tookhis titleas a variation on the title of Goropius Becanus's famous book about the hieroglyphs, Hermathena, published by P1.67d) an ancientdouble herm;thusit seems possible Plantinat Antwerpin I580. Puteanus (as in n. 7), pp. 10, 13-16, esp. p. I5: '... et that,ratherthan being an independentinterpretation, 85as the image mighthave been based on a half-understood numina misceo MUSARUMPALLADISQUE; ut terrenum account ofthe 'Rubensian' Hermathena (which had been melos coelesti septem orbium dulcedine concors, provided by Peiresc or one of Rubens's other French sacrum MUSATHENAEfiat, velut novae Deae.' Puteanus friends).But it would appear that Montfaucon,who talkslaterof9 Muses, but is perhapsalso alludingto the thatthe Muses were 7 in number(cf.notably, in themon tradition used Peiresc's papers, did not findanything Valeriano [as in n. 10I], fols theHermathena. ['de literis 349v-35Ir 81 See Judson-Van de Velde, I, pp. 255-60, nos. 60, septem']). Puteanus's commentson Calliope may also Rubens: see above, n. 7. 60a, and n, pls 204-07; Held (as in n. 30), I, pp. 422-23, have influenced 86 Musathena, p. 12. This was reprintedwith Philip no. 307 and n, pl. 306. 82 VoorhelmSchneevooght(as in n. 78), p. published) 161,no. 51. Rubens's otherworksin his (posthumously Van Dyck) has the editionofAsterius, Homiliae, Pontiusafter Rubens's portrait Antwerp161I5, (after P- I14. attributesof cornucopia and (Jupiter's) thunderbolt, 87 Bauhuis's poems are mostlyof a serious, religious to worksofart. whereas character,quite oftenmakingreference ofinvention, his power and fertility suggesting has Interestingly, Van Dyck's (after Pontius after a self-portrait) however, his most famous lines were and thedoves ofVenus. The printwas published perhaps the couplet fromone epigram (B. Bauhusius flowers Antwerp1634, IV, p. 74), listingthe by F. Huberti,presumablysome timeafterthedeath of etc., Epigrammata, Rubens and of Van Dyck. The 'Woverius' Hermathena names of the Muses - making 'nine girls stand on Poeta Undenis ecce, was also adapted, with the hats made smaller and the eleven feet' (... Lepidusnoster iubet,

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REMBRANDT'S

WOMAN TAKEN IN AD ULTERY

245

op. cit., esp. pp. 16-26 and 77-80) several (who does not seem to have regarded his Jaff6, conjunction as anything more than a verbal pages appear to be copies after Rubens of double busts of the type recorded in the play),88 Rubens was as an artist able to give a fanciful convincingvisual formto his ingenious conceit. drawings in the British Museum (Pl. 67b-d). Fol. 12or has a bearded and an elderly bald Postscript man, identified,I think wrongly,by Maurice Arnout Balis, who is reconstructingRubens's Johnson, the manuscript's eighteenth-century lost notebooks for the volume on the artist's owner (see Jaff6, op. cit., p. 78, n. 3), as theoretical studies in the Corpus Rubenianum 'Hercules' and 'Mercury' [i.e. a Hermeracles]; has kindlydrawn my attention fol. 12 Ir shows 'Democritus' and 'Heraclitus' LudwigBurchard, to a reference to herms and to the Hermathena in (this time with inscriptions evidently copied The'orie de la figure considerie dansses from Rubens, including the instruction that humaine, thle soiten repos ou en mouvement. principes, Ouvrage Democritus's forehead should look rather like traduit du latinde Pierre-Paul avecXLIV that of Silenus: 'praeferataliquot ut [?] sileno'); Rubens, Planches d'apris les fol. 122r illustrates a 'Venus' and 'Mercurius grave'es par PierreAveline, dececiltbre desseins at Paris by leno' ('Mercury the pimp') with the face of an Artiste, published C.-A. Jombert in 1773. The relevant passages old woman ('facies anilis') [i.e. a playful and fol. 123' joins masks of (PP. 34 and 42-43) are translated from Hermaphrodite]; Rubens's original Latin as recorded in the MS 'Comedia' and 'Tragedia'. On fol. 120" is a de Ganay, a late seventeenth-century copy of note, connected with the drawing on the recto, material fromRubens's so-called 'pocketbook'. on the idea of combining black and white heads (For this manuscript see M. Jaffe, Van Dyck's (cf. n. 46 above) in an image ofebony and ivory London 1966, esp. pp. 32-42 (the black one having ivory teeth and eyes), Antwerp Sketchbook, and 89-91.) Rubens describes herms (p. 34) as with reference to statues ofelectrum described by busts on square bases, eithershortor fulllength Pausanias [v, xii, 7: making it clear that by - oftenpedestals on which the heads could be electrum Rubens means amber rather than the changed but normally depicting Mercury alloy ofgold and silver]. Arnout Balis, to whom himself (hence the name) [cf. n. 53 above]; he I am also indebted for the MS Johnson also associates them with tombs. Then, follow- references,believes that these pages were not ing some observations on different aspects of copied from the 'pocketbook' itself but were ancient iconography, he introduces (p. 42) the added byJohnson fromother Rubens material Hermathena: I, 4, 3: cf. he had acquired. Thus the question about the citing Cicero (ad Atticum, n. 51I above), he relates Hermathenae to other function of Rubens's own amusing variations herms ('des piedestaux ... dont les tites on the Hermathena theme (P1. 67b-d) is likewise pouvoient se changer'), and defines them as stillopen. heads of Mercury and of Minerva joined ELIZABETH MCGRATH together, the word Hermathena deriving from WARBURG INSTITUTE their Greek names. Whether Rubens ever intended to expand on and publish his theoryis, therefore,still unclear. Moreover, in the MS Johnson, now in the Courtauld Institute,which also preserves part of the artist's lost notes (cf.

starenovem pedibus)- which caught on as a Nymphas mnemonic forschoolchildren.See A. Tooke, The Panthe Histories Fabulous Heathen Gods theon, representing ofthe ..., edn London 1783, p. I89. 88 In discussingthe Hermathena of Cicero Puteanus (as in n. 7, P. I5) simply talks of how the ancients made Mercuryaccompany Minerva: 'Mercurium antiquitus Minerva admisit,et HERMATHENAfacta.' To justifyhis combinationof Minerva and the Muse(s) he mentions (p. I6) an image, a coin sent to him by Pignoria which shows an owl on top of a lyre; but thisis evidently not seen as an illustration ofany ancientMusathena.

and Courtauld Volume 5o, 1987 Journalof theWarburg Institutes.

REMBRANDT'S

WOMAN TAKEN IN

AD ULTERY

taken in Adultery (P1. 71) REMBRANDT'S Woman is exceptional in the exactness and lucidity with which it presents the central episode, with his biblical scenes despite all its affinities and other comparably scaled pictures of the

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

:?.--:-. -:--.-:~---:_--:? :::?'::: _ . ?-:

li-4-ii~i.

:`~:-_:::: :-: :-n:i::,,c:--~

:_:?:

a-Rubens, Design fortitle-pageofBauhuis etc.,Epigrammata. Antwerp,Plantin-Moretus Museum (pp. 233, 237f)

Plantin-Moretus Museum Copyright

C M (P

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

on coin ofHadrian, fromDu a-'Apollo Citharoedus' edn Lyons 1581 (p. 234) Choul, De la religion,

?i;

b---Muse withfeatherand Apollo. Detail from sarcophagus, Woburn Abbey

(p.235)

.a

c-Rubens, Design fortitle-pageto Sarbievius, Lyrica. Antwerp,Plantin-Moretus Museum (pp. 237f)

d-Sarcophagus withcontestofMuses and Sirens. New York, Metropolitan Museum (p. 236)

All rights reserved: Metropolitan Museum ofArt,RogersFund

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

J:

?,i

bJ

a-Double herm ofDionysus and satyr. From Statius, Illustrium virorum... Rome I 569 vultus, (PP. 238, 243)

b--Rubens,Double bustofSilenusand satyr. Museum(p. 238) London,British

ii

d-Rubens, Hermathena. Museum London,British

(pp.238, 244)

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S A P Eiiiiiiii:i N iiiii I A ::-------:: MO D FS :T : :--::: :::::::-:: ::: :: --:-: :: ::- :: IAi i iiiiii:: i:iiii iiiiiii~iii-iiii i-iiiii:ii---ii :-::::::-:::--:-:---i-i-:i-:i_-_:__PR O GRESSJ i i~~ TIAMiiiiiiiiiii i:-i::_::;_::_iiiiiii ::: ELO Q V EN ::::::-~--i:-i-:--i:-ai:-i::::::--:-:--:-::i-i1 :LI IT TE :-: PE::::: i::--::kFIC IT::::::::1::::::: :::::: HAEC ::::: S ib y n C II :::;:_--_--__::i:: :::::,:_-::::::::::_: :i____ :____

:::: ::: : : ::: ::: :: :-: ' ::: ::: ::: ::: :::::' -::::-: :-:-: -:-:-: ::::i::: ::::-:::::::i:::: ::: :: :: ::::-_,--__::--__:--:-::_ -;:: :::::::: :--_-_-:~i:i-i-:-i:i--:_?---_-i--i:--: :~ :: :: ::::::::::: -_:_::-ii-_:-:-: ::-:-__-__---::::: :: :: :-: :::::::::::-::::::: ::::::::: :~:: ::::::_:_: ::::::::---:: :::: :: :: -:-: :::::: : '-':'-'-'-'----:-':':'-i:-:i:iiiiiiiiiii ~-E?1~1??i ".t.:'~,~i,~-" -:-----::--:-:-::-::----::---:::-:--:::-:-' :-:--:: ::i: --_-_:_iiiiiii----':i-i--:-_-:-::_--i---:: ::-::-::_:-:::-:::::::_:-::-::::::ii:i-i ::-::-:---:i:-----i:----':---...-.w :-:--::-:--:-:--:---:-::-------:-: :::: :-:::::i-l:-:~_i'ii-i:i-ii:i:ii:_i:i i:i~i:iiii: _-i ii:ii:: _i-iii--_-_:ii-i :::: :-:::::::::::::: :-:--_:: _:::::-:_::--_---:--:--::-:-::::: -:::-::--:-:.. _-_--_:_::: _:-:--_---,:-iiiii':iiiiiiiisiiiiii-~i~ ::: i-i-iiiiiiiiiiiiiii:::: --:ii-i:i--::: -:-: -:-:--:::-::::-:: ::--:-:::: ---:-::: -:::-:--::: :.. :: '---:: :::::::-::: ::::: :-:-::--::: -::::':':-'iiiii iiii-i::: ::::::::: '-"-:--:-:":':iiiiiiiiii:i---_:----_-:':i:~i-i:-i ii-i ii-i:i-i--i: i-i-i -i--: -:-:----::i:--iliiiiiii-i-i-iii~i:i-ii:i:ii-~::-~:i--i-iiiiiiiiiii--::: :':" i:i~i:ii-iii-i-i:i--:: ::::-:-:::::::: ::: :--: ::: ::::: -:'. ::-:-: ':-:--:-:::::----:-::::::: : : :::i:i-i~ili:-: ::: ::-::i:::::::i:::-:: ::-__----ii-_-:--:-::--:ii:i:ii-: _:- ::-:--:-: :::-:::-:-----:::::1::::: ::: :: :::::::: ::: ::: :::: :::::;:-:-: -: :---:-_:i--_::-:---:_--__-. :::::: : :: ::::::: : :::: :::: -_ :::::_-_:-:--:--:--: ::: :::: ::::-::::-::-::::::: ---ii-i-i~ii:i--i-i i:i-~iiiiiiii "-i ii-i:ii-i -i:i-i--i:i-_ :::-:-:: ---:-::--:::---:: ::::: ::--:::-::-:-: -i:i--i--_i:i _---iii-ii:i-i i:i :: ::: --:--::--_-i-i--::: : :-: :::::-:::::-:--:-------:-:;::::-I ..... ::::-----:'-:-:-:-:;----iiiii~-ii-iiiiiiii~i~iiiii: :-:-----:--_:---i_-: -_:::-:__----: -_::--i:i:-:--:::-::::-: -:-: :::::: :::::::::: ii~i-i--i i-i-ii-i:ii--i-i~i:i--i-ii-i~i-i ---::-_:---_-_:-::----_-i--i :----: ::--'-":--:-----: ---::':'-:::::---:-:---::::-:---::-::-:--'-:::1:: :: :::: :::i: ::---:-----'i:i-i-i-i-i-i----: --'::-:---'--:-:-:--'::----'-: ::::::::i:-:: :-----~_:_:::-:-:-----_---:::: ::::;:-::::_:i:::::::: .: ::~i~ii:-:ii~-iD~:i:i:i-l'i~:iili~~~iili :i-i-iili iiii:i:i-:i:i-_ili:i:i-~-i-i: _i-iii -iiii iiiii''" '::::.:. :::::::::::::: ::::i:: ::::i:iiiiiiiii~i-iii-i:~iEi-i~ii:i~ii :-:-:-:ii-i-i-------:: _::-:i-i:i-i:-----:-_::_:-: _:::: :_::::-:~iiiii~ii:i :i-iiiiiiiiiiiiii-i~i:;i-,-::-:-:--:-: ---~i-i~i-i-i:i~iiiiiiiii-i------_ :-:,:::::::: :::; :::::-::-::::_ -::::::-;::-::_::::_:-_:-::::::::~:::--:-:-::::1: i:i-i-ii-ii--i-ii-i-i _i:i-ii:i-i i:ii~iii-i:--::-i-i-i--i-i:::i:-::-:i'-i :::::::::::::: ::--:--I_::::::-: :::--:--::::: ::::::-::: ::: -:--;-:::.::-::----:::-_----:ii:---_:i: _:-_:_:-:_:::: ::::-ii-i~i:-:ii-i:ii-i:~_i-i~i:i :-iiii:i-i:i:--_-::ii::-_:--:::_: _ ::::: ::::: ::::::::::: -:: ::;:::-i:i--:-::--::;:_::-:::-:::::::::: ::: :::: iiiii iii _i:i:i-i-i-iiiiiiiiiii-i-i:i :ii-i-i~iiii-i-i :-: :::: ::-iiiiiiiii: -:::-iiiii~ii: iiiii i:ili-i:~ ::::::--:---i-i:----::-:::~-:--::-:---::-:-:---::::-:-:-::-_:-:-:-----: ::::-: ::: ::-:-j_:i_:-:-_:-::::::::::-:: :-::_:-: _-: --::----_----:-__--::::::::: ::: ::: ::: -::::::::::::: 1::::,::: :::::::::::: :::::: :::: ::: :::: ::::::: :::::::: :: :-::---:--.: -:-?:_:::: ::::: :: : :::: ::::::::: : :: ::::: _i:i::-:-----i:ii-i: --:-iiiii-i--i:i:i ::::::-:---:-;::-:-iiiiiii ii:i-_i:iiiii ii~i:i--i-i-ii i:ii-i-i~iiii i:i~ : : ::: -:-::-:-::i-_-::: ::::-:::::-: ;i:i::: :: -i-iiiii~:i:iiiiiiii~i~iii-ii~:iiiii -::-::--::::::::::-:: :::: : -':'-::::-:-:-: ': ..:.-::-::-:_:: --:-:ii:i-i~i:---i-i-~:::::::::: -:----::::-:-:----:---'-:-:--'~-i:-i-i-i-ii-i iii~iiiiiii~i-i-iiiiiii~iii~i-i:~-i-~i:: :::::::: :::::::::i:::::::: ::::::::::-:-:--:-:: :-----:: ::: --:: :: ::::;::::-:i_:-i

'-:: ??i-; ? ~?1 ~?-; ~?,

::: : .: : :. N ii ::iii:l:i ..... O .: :::_::..:.:i SiCiAiESTiiii

... .ii:iiiiii:: :::..:: : ::::: :: ::.:. iii-iiiiiii~iiiiiii

: ii : :. ..:: ::: i-iiiiiiiiii-

-iiiiiiiiiiii i: i: :: -:--:ii-i i --- -:-::::::::: iii:-i:ii~-~ ii~ .. i---_--:-:' i~-iii --___-::: __::::_: :::_: :_::( _ :l::__: :,::::::::i: :_-:: _:-: --_: -_: -::::-::--: it :::::::: ::::-:::: :::-i:::::,

:i :. ii-: ii-i~i:i-iiiiiiiii -i-ii,

a-Hermathen (pp.240f) :::::::::i::::::::.:::_:__j~ii:_::

~--'On

not

(PP.24?of)

leaving

a house

unfinished'

c--'Home lif

a-c: From Bocchi, Symbolicae edn Bologna I574 Quaestiones,

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

a--F. Zuccari,

241) (p. Farnese Palazzo Zuccari, Caprarola, a-F. Hermathena. Caprarola, Palazzo Farnese (p. 24r) Hermathena.

Photo

GFN,

Rome

b-A. Sadeler af Hermathena (p. 2

This content downloaded from 2.33.41.233 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 05:47:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70

RUBENS'S

MUSA THENA

iiiii'ii

:----;i::ii-----:-

i-,i

:-

Rome 1570 (p. 242) Imagines,

b

from a-Hermathena Orsini,

b-Illustrationtoa thesis from the Accademia Milan I1624 Ermatenaici, degli

(p.242)

mark c-Rubens, Designfor printer's Meursius. ofJoannes Antwerp,