Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

HIV and HCV Interactions

Caricato da

fahri_amirullahDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

HIV and HCV Interactions

Caricato da

fahri_amirullahCopyright:

Formati disponibili

UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA, MEDICAL MICROBIOLOGY

HIV and HCV interactions in end-stage liver disease

How things can always be worse...

Jonathan Audet 12/7/2011

Key points:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects about 30% of HIV patients and as high as 90% of HIV positive IV drug users. It also dramatically reduces life expectancy. HIV can kill and/or sensitize hepatic cells resulting in liver injury. The damages caused to the immune system allow increased replication of HCV and thus, increased damage. The depletion of Th17 cells in the gut might be an important factor in accelerating liver fibrosis, as hepatic stellate cells are stimulate by the microbial products that leak through the gut and secrete profibrotic cytokines and collagen type I. HAART agents have become less hepatotoxic and are therefore of great help in the management of HIV in coinfection patients.

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

Introduction

As of their 2011 Global HIV/AIDS Response Progress Report, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the number of people living with HIV to be approximately 34 million worldwide. (1) Despite modern therapies, which increase the lifespan of those who are infected, there are no treatments and no vaccines currently licensed for HIV. The main route of transmission is through sexual intercourse, although tainted blood (such as on needles used by drug users or blood used for transfusions) can also transmit the virus. It is currently estimated that 20-30% of HIV patients are also infected with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), this fraction can go up to 90% among IV drug users. The main route of transmission of HCV is through contaminated blood, usually from re-use of syringes or from blood transfusions. It can also be transmitted through sexual intercourse, albeit less frequently. The shared routes of transmission mean that high-risk behavior for one virus also predisposes to being infected by the other. Those patients coinfected with HIV and HCV usually have a dramatically reduced life expectancy due to the acceleration of liver damage. For example, those infected with HCV alone will be chronically infected for about 23.2 years at the onset of cirrhosis, whereas in those coinfected with both HIV and HCV the onset of cirrhosis happens around 6.9 years after HCV infection. (2) The present summary will, first, present some background information about liver physiology, the immune system and viral pathogenesis; then discuss how these three aspects interact to aggravate and accelerate the progression to end-stage liver disease (ESLD).

Background

Physiology Kupffer cells are macrophages found in the livers blood vessels, they are specialized for the removal of erythrocytes and complement covered microbes (Figure 1). They also possess the TLR4 receptor, allowing them to sense LPS. Upon LPS stimulation, Kupffer cells will secrete reactive oxygen species (ROS) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (3) which will stimulate hepatic stellate cells (HSC). (4) The HSCs will then upregulate TLR4/CD14/MD2 and also start producing profibrotic cytokines and collagen type I. (4) Immunology: The Th17 response Of the 6 currently known T helper differentiation paths, the Th1 and Th2 are the most studied. In the case of HIV enhanced liver disease however the Th17 response is suspected to be quite important.

Jonathan Audet1 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

The Th17 response is mainly responsible for mucosal extracellular pathogen monitoring and response. Th17 cells are enriched in the lungs and the gastro-intestinal tract. The hallmark of these cells is the production of IL-17 and IL-22. There have been reports that IL-17 induces the formation of tight junctions in intestinal epithelial cells (5).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection with HIV normally starts with the infection of macrophages or dendritic cells at mucosal surfaces. The virus will then be transmitted to CD4+ lymphocytes and spread mainly in that cell population. There have been reports of HIV causing direct death of hepatocytes through CXCR4 signalling by gp120 (6) and indirectly by increasing TRAIL sensitivity in hepatocytes (7) . Also HIV increases CD4+ T cell death by increasing both Fas and sFasL expression (8).

HIV produces an initial acute infection that gets rapidly controlled by the immune system and transforms into a chronic infection inducing a high turn-over of CD4+ T cells.

Hepatitis C Virus HCV is a positive single-stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. It causes a hepatitis that can be acute and cleared by the immune system (10-60% of cases (9)) or go on to become a chronic infection. One of the strategies for the virus to escape clearance is to possess a high mutation rate. Similar to HIV, HCV needs to copy its genome, although it makes a negative sense RNA copy and not a DNA copy, and this step in viral replication is very error- prone. This allows the virus to generate quasispecies and means that most people infected with HCV can carry viruses that are quite different from one another. (10)

The currently accepted treatment for HCV infection is pegylated interferon and ribavirin (11), although there are two new drugs approved in 2011 by the FDA. HCV has been shown to increase Fas expression on CD4+ T cells but not soluble FasL (sFasL) which leads to increased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis of CD4+, but the virus itself does not produce the increased apoptosis. (8) There have also been reports of HCV infecting non-hepatic cells, including T and B cells. (12) An untreated, or unresponsive, hepatitis C infection will usually result in a cirrhotic liver that can develop hepatocellular carcinomas. In cirrhosis, the parenchymal tissue in the liver, i.e. the actual hepatocytes, will be slowly replaced with scar tissue and collagen leading to a loss of function of the liver. The only treatment for a cirrhotic liver is transplantation.

Proposed interactions

Jonathan Audet2 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

There are two ways HIV can aggravate the damage caused by HCV: 1) indirectly, by damaging the immune system, HIV can allow HCV to cause more damage to the liver; and, 2) directly, by sensitizing the liver cells or otherwise increasing hepatocyte death.

Indirect: How immune system pathologies contribute to liver disease Because both viruses increase the expression of Fas on CD4+ T cells, these become highly sensitized to the action of sFasL and will be depleted quite efficiently by the increased that HIV provokes. (8) Here, these viruses act synergistically to deplete the CD4 population. Because CD4+ T cells are orchestrators of the immune response, the efficiency of the anti-HCV response is diminished and more liver damage can result.

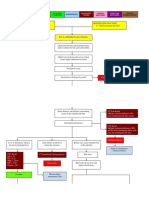

The persistence of the antigens will also bring CD8+ T cell exhaustion which will reduce the effectiveness of the immune response to both viruses, but mainly allows for increased HCV RNA levels in the blood, indicating more replication is probably happening in the liver. Because Th17 cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells, they can and are infected by HIV. This is especially true in the gut epithelium. In a normal individual, when the tight junctions between the enterocytes start to loosen, microbial products such as LPS and DNA cross into the tissue (microbial translocation) and blood and stimulate the immune cells that reside in the gut. Upon stimulation Th17 cells will secrete large amounts of IL-17. This cytokine tends to stimulate the formation of tight junctions and restores the integrity of the epithelium. (4,13) In contrast, during HIV infection, Th17 cells are effectively depleted in the intestinal mucosa, leading to loss of integrity and increased microbial translocation. This increase in microbial products stimulates Kupffer cells and HSCs, the latter increase the rate at which they produce profibrotic cytokines and deposit collage type I. (4) This hypothesis, however, has yet to be clearly demonstrated. (Figure 2)

Direct: Possible interactions between the viruses

It has recently been shown that HIV can increase the sensitivity of hepatic cell lines to TRAIL-induced apoptosis or even cause cell death. (6,7,14) This research indicates that even without including immune system pathologies, the presence of HIV (more precisely of gp120) sensitizes hepatocytes, increasing the damage due to the HCV infection. (Figure 3) There is also indication that the presence of surface proteins from both viruses (gp120 from HIV and E2 from HCV) triggers the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in a p38-dependent, N F-B-independent manner. (15)

Jonathan Audet3 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

Effect of HAART on the immune response to HCV

When Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART) was first introduced, many of the compounds used had significant hepatotoxicity. Nowadays, many first-line HAART agents have an acceptable liver safety profile and are acceptable as treatment during HIV/HCV coinfection.

(16)

Conclusions

HIV/HCV coinfection is still at a very high prevalence and has major effects on survival and quality of life. Nevertheless, the advent of liver-friendlier HAART to control HIV replication and damage and of direct acting antivirals against HCV allow us to look forward to mitigating, at least, the effect of this deadly virus combination.

Bibliography

1 WHO; UNAIDS; UNICEF. Progress report 2011: Global HIV/AIDS response. World Health Organization, November 2011. Disponivel em: <http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/proress_report201 1/summary_en .pdf>. 2 PETROVIC, L. M. HIV/HCV co-infection: histopahtologic findings, natural history, fibrosis, and impact of antiretroviral treatment: a review article. Liver Int, p. 598-606, 2007. 3 WHEELER, M. D. Endotoxin and Kupffer cell activation in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Research & Health, v. 27, n. 4, p. 300-306, 2003. 4 PAGE, E. E.; NELSON, M.; KELLEHER, P. HIV and hepatitis C coinfection: pathogenesis and microbial translocation. Cur Opin HIV AIDS, v. 6, p. 472-477, 2011. 5 KINUGASA, T. et al. Claudins regulate the intestinal barrier response to immune mediators. Gastroenterology, v. 118, n. 6, p. 1001-1011, 2000. 6 VLAHAKIS, S. R. et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-induced apoptosis of human hepatocytes via CXCR4. J Infect Dis, v. 188, n. 10, p. 1455-1460, 2003. 7 BABU, C. K. et al. HIV induces TRAIL sensitivity in hepatocytes. PLoS ONE, v. 4, n. 2, p. e4623, 2009. 8 KRNER, C. et al. Hepatitis C coinfection enhances sensitization of CD4+ T-cells towards Fas-ind uced apoptosis in viraemic and HAART-controlled HIV-1-positive patients. Antivir Ther, v. 16, p. 1047-1055, 2011.

Jonathan Audet4 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

9 CARUNTU, F.; BENEA, L. Acute hepatitis C virus infection: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, treatment. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis, v. 15, n. 3, p. 249-256, 2006. 10 ROSEN, H. R. Hepatitis C Pathogenesis: Mechanisms of viral clearance and liver injury. Liver Transplant, v. 9, n. 11, Suppl 3, p. S35-S43, 2003. 11 CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION. Hepatitis C -STD Treatment Guidelines 2006, 2006. Disponivel em: <http ://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/hepatitisc. htm>. 12 REVIE, D.; SLAHUDDIN, S. Z. Human cell types important for Hepatitis C Virus replication in vivo and in vitro. Old assertions and current evidence. Virol J, v. 8, p. 346, 2011. 13 DANDEKAR, S.; GEORGE, M. D.; BUMLER, A. J. Th 17 cells, HIV and the gut mucosal barrier. Cur Opin HIV AIDS, v. 5, p. 173-178, 2010. 14 JANG, J. Y. et al. HIV infection increases HCV-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. J Hepatol, v. 54, n. 4, p. 612-620, 2011. 15 BALASUBRAMANIAN, A.; GANJU, R. K.; GROOPMAN, J. E. Hepatitis C Virus and HIV envelope proteins collaboratively mediate interleukin-8 secretion through activation of p38 MAP kinase and SHP2 in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem, v. 278, n. 37, p. 35755-35766, 2003. 16 JONES, M.; NEZ, M. HIV and hepatitis C co-infection: the role of HAART in HIV/hepatitis C virus management. Cur Opin HIV AIDS, v. 6, p. 546-552, 2011.

Figures

Jonathan Audet5 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

Figure 1: Basic liver structure. From Frevert et al, PLoS Biology, 2005

Figure 2 Microbial translocation as a factor in acceleration of cirrhosis. From Page et al, 2011.

Jonathan Audet6 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

Jonathan Audet7 | Page

MMIC 7050

HIV & HCV in end-stage liver disease

Figure 3 Increase in TRAIL and TRAIL receptors increases cell death. From Babu et al, 2009

Jonathan Audet8 | Page

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 4.8 Anatomy - Radiology of The AbdomenDocumento14 pagine4.8 Anatomy - Radiology of The Abdomenmerkogm100% (1)

- Chapter 32 Gallbladder and The Extrahepatic Biliary SystemDocumento81 pagineChapter 32 Gallbladder and The Extrahepatic Biliary SystemAlexious Marie Callueng100% (2)

- Clinical Imaging of Liver, Gallbladder, BiliaryDocumento93 pagineClinical Imaging of Liver, Gallbladder, Biliaryapi-3856051100% (1)

- Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocumento45 pagineHepatocellular Carcinomamhean azneitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Viral HepatitisDocumento53 pagineViral HepatitisAmer JumahNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathophysiology - Obstructive JaundiceDocumento3 paginePathophysiology - Obstructive JaundiceAbigail Lonogan0% (1)

- Bilirubin Metabolism: Hd. - Msc. (Biochemistry)Documento18 pagineBilirubin Metabolism: Hd. - Msc. (Biochemistry)MuhamadMarufNessuna valutazione finora

- Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Primary Sclerosing CholangitisDocumento44 paginePrimary Biliary Cirrhosis Primary Sclerosing CholangitisTK RowlingNessuna valutazione finora

- Envejecimiento HivDocumento8 pagineEnvejecimiento HivJose LunaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis: Cupenhqen Journal of Hepatology IssnDocumento15 paginePathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis: Cupenhqen Journal of Hepatology IssnahmedlakhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rough WorkDocumento4 pagineRough Workabdullah khanNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatitis CDocumento9 pagineHepatitis CAhmed FaizNessuna valutazione finora

- HEP-Adaptive Immune ResponsesDocumento7 pagineHEP-Adaptive Immune ResponsesoomculunNessuna valutazione finora

- Virus-Related Liver Cirrhosis: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic OptionsDocumento14 pagineVirus-Related Liver Cirrhosis: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic OptionsJamesNessuna valutazione finora

- Manifestari ExtrahepaticeDocumento9 pagineManifestari ExtrahepaticeIulia NNessuna valutazione finora

- Therapy For Persistent HIVDocumento6 pagineTherapy For Persistent HIVAnonymous ceYk4p4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nihms 839861Documento40 pagineNihms 839861Faisal JamshedNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 Pathogenesis of Viral HepatitisDocumento5 pagine8 Pathogenesis of Viral HepatitisMedhumanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gastrointestinal Tract and HIV Pathogenesis: Invited CommunicationDocumento4 pagineThe Gastrointestinal Tract and HIV Pathogenesis: Invited CommunicationnikkennnNessuna valutazione finora

- Apoptosis in Hepatitis C Virus InfectionDocumento11 pagineApoptosis in Hepatitis C Virus InfectionHNINNessuna valutazione finora

- ACLF in ICUDocumento42 pagineACLF in ICUEric CharpentierNessuna valutazione finora

- Changes in the co-expressions of interleukin 29 (IL-29), IFN-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) and monokine induced by IFNγ (MIG) genes in chronic hepatitis C Egyptian patients untreated and treated with DAAsDocumento8 pagineChanges in the co-expressions of interleukin 29 (IL-29), IFN-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) and monokine induced by IFNγ (MIG) genes in chronic hepatitis C Egyptian patients untreated and treated with DAAsAhmed AmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Report On Hepatitis VirusDocumento85 pagineProject Report On Hepatitis VirusBrijesh Singh Yadav100% (1)

- Alteraciones Inmunologicas en VHC WJG 2013Documento9 pagineAlteraciones Inmunologicas en VHC WJG 2013jimotivaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hbsag HbcagDocumento2 pagineHbsag HbcagRysna AzizahNessuna valutazione finora

- NHLBI Workshop Summary: Pulmonary Complications of HIV InfectionDocumento7 pagineNHLBI Workshop Summary: Pulmonary Complications of HIV InfectionSiska TariganNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Clinical Investigation of Hepatitis C and Virus 1Documento6 pagineRunning Head: Clinical Investigation of Hepatitis C and Virus 1Ngu W PhooNessuna valutazione finora

- Firdaus 2014Documento8 pagineFirdaus 2014Pavithra NNessuna valutazione finora

- HepatitisDocumento6 pagineHepatitisJulian VasquezNessuna valutazione finora

- An Overview of The Mechanisms of HIV-related ThrombocytopeniaDocumento17 pagineAn Overview of The Mechanisms of HIV-related ThrombocytopeniaMesay AssefaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vassilopoulos 2002Documento13 pagineVassilopoulos 2002deliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatitis C Is A Blood Borne Liver DiseaseDocumento5 pagineHepatitis C Is A Blood Borne Liver DiseaseSania Kamal BalweelNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Mid Final AssignmentDocumento19 paginePost Mid Final Assignmentwaqar627926Nessuna valutazione finora

- HepatitisDocumento11 pagineHepatitistorsedepointeNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 3 Infectious Hazards of TransfusionDocumento5 pagine5 3 Infectious Hazards of TransfusionCommandNessuna valutazione finora

- Pato HEP BDocumento6 paginePato HEP BErena HairunisaNessuna valutazione finora

- "Wrapped Up" Vaccines in The Context of HIV-1 ImmunotherapyDocumento50 pagine"Wrapped Up" Vaccines in The Context of HIV-1 Immunotherapykj185Nessuna valutazione finora

- Molecules: Viral Hepatitis and Iron Dysregulation: Molecular Pathways and The Role of LactoferrinDocumento21 pagineMolecules: Viral Hepatitis and Iron Dysregulation: Molecular Pathways and The Role of Lactoferrint.araujoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gen Patho AIDSDocumento22 pagineGen Patho AIDSJireh MejinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacterial Infections in CirrhosisDocumento8 pagineBacterial Infections in CirrhosisandreeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interferon Stimulated Genes and Their Role in Controlling Hepatitis C VirusDocumento11 pagineInterferon Stimulated Genes and Their Role in Controlling Hepatitis C VirusKarim ElghachtoulNessuna valutazione finora

- Viral Hepatitis C: Thierry Poynard, Man-Fung Yuen, Vlad Ratziu, Ching Lung LaiDocumento6 pagineViral Hepatitis C: Thierry Poynard, Man-Fung Yuen, Vlad Ratziu, Ching Lung LaiAndres GalárragaNessuna valutazione finora

- Immunology of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus InfectionDocumento15 pagineImmunology of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus InfectionMark BowlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Papr2 PDFDocumento5 pagineResearch Papr2 PDFShweta MaheshwariNessuna valutazione finora

- Bdb06ff135c7ccb File 2Documento29 pagineBdb06ff135c7ccb File 2Mary ThaherNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatitis A-PrintDocumento17 pagineHepatitis A-PrintVirginia EchoNessuna valutazione finora

- Liver DiseaseDocumento19 pagineLiver Diseasenishi kNessuna valutazione finora

- Frances 1Documento9 pagineFrances 1Alfonn Fernandez MonescilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Hepatitis C: Immunology Lab ResearchDocumento21 pagineHepatitis C: Immunology Lab ResearchLeon LevyNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Words: Chronic Virus Hepatitis, PlasmapheresisDocumento16 pagineKey Words: Chronic Virus Hepatitis, PlasmapheresisEliDavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Hiv 151105074504 Lva1 App6891Documento2 pagineHiv 151105074504 Lva1 App6891Haris QurashiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hiv 151105074504 Lva1 App6891Documento2 pagineHiv 151105074504 Lva1 App6891Muhammad KaleemNessuna valutazione finora

- Articulo ADocumento8 pagineArticulo AJaver Andres HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar: Daniel P Webster, Paul Klenerman, Geoff Rey M DusheikoDocumento12 pagineSeminar: Daniel P Webster, Paul Klenerman, Geoff Rey M Dusheikovira khairunisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Epstein-Barr Virus-Related Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder in Solid Organ Transplant RecipientsDocumento10 pagineEpstein-Barr Virus-Related Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients19112281s3785Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hcca Rev Nri 2005Documento15 pagineHcca Rev Nri 2005Patrick RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Fibrosis Assessment in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) InfectionDocumento14 pagineFibrosis Assessment in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) InfectionKevin KusumanNessuna valutazione finora

- HIV Nephropathy - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento5 pagineHIV Nephropathy - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfEmmanuel SoteloNessuna valutazione finora

- Khvi 17 1819742Documento24 pagineKhvi 17 1819742Sebastian BurgosNessuna valutazione finora

- Extrahepatic Manifestations of Chronic HCV Infection: Alessandra Galossi, Riccardo Guarisco, Lia Bellis, Claudio PuotiDocumento9 pagineExtrahepatic Manifestations of Chronic HCV Infection: Alessandra Galossi, Riccardo Guarisco, Lia Bellis, Claudio PuotiAlex TimofteNessuna valutazione finora

- D Sousa 2020 Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Hepatitis Induced Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocumento26 pagineD Sousa 2020 Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Hepatitis Induced Hepatocellular CarcinomaLUIS �NGEL V�LEZ SARMIENTONessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Viral Hepatitis-Beyond A, B and CDocumento13 pagineAcute Viral Hepatitis-Beyond A, B and CSelvi Putri OktariNessuna valutazione finora

- HBV HCV 1Documento13 pagineHBV HCV 1Vũ Minh KhoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Zepatier As An Improved Drug Treatment For Hepatitis C Genotypes 1 and 4Documento10 pagineZepatier As An Improved Drug Treatment For Hepatitis C Genotypes 1 and 4api-317047226Nessuna valutazione finora

- Giovanna FatovichDocumento16 pagineGiovanna FatovichGilang Kurnia Hirawati0% (1)

- Viral Hepatitis: Acute HepatitisDa EverandViral Hepatitis: Acute HepatitisResat OzarasNessuna valutazione finora

- Fat PTC8Documento52 pagineFat PTC8vNessuna valutazione finora

- Rudiyanto, Liver FibrosisDocumento41 pagineRudiyanto, Liver Fibrosisbudi darmantaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nejms 1812.1Documento114 pagineNejms 1812.1andriopaNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Biochemistry: MSD Manual Veterinary ManualDocumento5 pagineClinical Biochemistry: MSD Manual Veterinary ManualDursa MiressaNessuna valutazione finora

- Polysorbate 80 and E-Ferol ToxicityDocumento7 paginePolysorbate 80 and E-Ferol Toxicityadrianoreis1Nessuna valutazione finora

- DatasheetDocumento21 pagineDatasheetSayuri SuárezNessuna valutazione finora

- Ayushman Spageric HerbalsDocumento6 pagineAyushman Spageric HerbalssubhalekhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 09,10 - Foundations of USG PDFDocumento78 pagineLecture 09,10 - Foundations of USG PDFWaqas SaeedNessuna valutazione finora

- Tüm Abdomen USDocumento2 pagineTüm Abdomen USradakahNessuna valutazione finora

- Materia Medica For The Digestive System: Digestive Bitters and CholagoguesDocumento4 pagineMateria Medica For The Digestive System: Digestive Bitters and CholagoguesMelissa NorthNessuna valutazione finora

- Homeostasis 121117100359 Phpapp02Documento68 pagineHomeostasis 121117100359 Phpapp02midahrazalNessuna valutazione finora

- Theme 5. Gallstone Disease-1Documento18 pagineTheme 5. Gallstone Disease-1HashmithaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cholecystitis FinalDocumento57 pagineCholecystitis FinalRajendra DesaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Fda Approved Contrast AgentsDocumento55 pagineFda Approved Contrast AgentsPoojaSolankiNessuna valutazione finora

- Stomach Bacterial Infection DiseaseDocumento69 pagineStomach Bacterial Infection DiseaseJeck OroNessuna valutazione finora

- Metabolic SD in Clinical PracticeDocumento268 pagineMetabolic SD in Clinical PracticePetzyMarianNessuna valutazione finora

- Liver CleanseDocumento1 paginaLiver CleanseasksreeNessuna valutazione finora

- P 2 Liver Disease PDFDocumento10 pagineP 2 Liver Disease PDFdereen NajatNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 16 - Digestive SystemDocumento12 pagineChapter 16 - Digestive SystemmargaretNessuna valutazione finora

- Patologi Sistem Pencernaan Hati Sesi 1aDocumento36 paginePatologi Sistem Pencernaan Hati Sesi 1adewinurfadilahNessuna valutazione finora

- Biliary Atresia:: Color Doppler US Findings in Neonates and InfantsDocumento8 pagineBiliary Atresia:: Color Doppler US Findings in Neonates and InfantsAdietz satyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathology MCQ - Liver and Biliary Tract PDFDocumento5 paginePathology MCQ - Liver and Biliary Tract PDFCHRISTOPHER OWUSU ASARENessuna valutazione finora

- COMPARISON BETWEEN ULTRASONOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL FINDINGS IN 43 DOGS WITH GB MUCOCELEchoi2013Documento6 pagineCOMPARISON BETWEEN ULTRASONOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL FINDINGS IN 43 DOGS WITH GB MUCOCELEchoi2013Thaís ChouinNessuna valutazione finora