Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Self-Respect. A Neglected Concept

Caricato da

coxfnTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Self-Respect. A Neglected Concept

Caricato da

coxfnCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [79.112.42.

116] On: 13 February 2013, At: 15:07 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Philosophical Psychology

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cphp20

Self-respect: A neglected concept

Constance E. Roland & Richard M. Foxx Version of record first published: 19 Aug 2010.

To cite this article: Constance E. Roland & Richard M. Foxx (2003): Self-respect: A neglected concept, Philosophical Psychology, 16:2, 247-288 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515080307764

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

PHILOSOPHICAL PSYCHOLOGY, VOL. 16, NO. 2, 2003

Self-respect: a neglected concept

CONSTANCE E. ROLAND & RICHARD M. FOXX

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

ABSTRACT Although neglected by psychology, self-respect has been an integral part of philosophical discussion since Aristotle and continues to be a central issue in contemporary moral philosophy. Within this tradition, self-respect is considered to be based on ones capacity for rationality and leads to behaviors that promote autonomy, such as independence, self-control and tenacity. Self-respect elicits behaviors that one should be treated with respect and requires the development and pursuit of personal standards and life plans that are guided by respect for self and others. In contrast, the psychological concept of self-esteem is grounded in the theories of self-concept. As such, self-esteem is a self-evaluation of competency ratios and opinions of signicant others that results in either a positive or negative evaluation of ones worthiness and inclusionary status. The major distinction between the two is that while competency ratios and others opinions are central to self-esteem, autonomy is central to self-respect. We submit that not only is self-respect important in understanding self-esteem, but that it also uniquely contributes to individual functioning. Research is needed to establish the central properties of self-respect and their effects on individual functioning, developmental factors, and therapeutic approaches.

1. Introduction The development of ethical and moral standards in children is essential to the welfare of any society (Damon, 1993). This effort includes the teaching of the rules and norms of society and extends to the quest to nd meaning or signicance in ones life (Kane, 1994). Although this quest begins with moral education and engagement in ethical living, there is mounting evidence that these processes have become more difcult and more precarious as society has become more complex (Kane, 1994). Crucial to the accomplishment of these lofty goals is the selection of a concept of self that promotes the development of personal growth and standards of behavior. While psychology has generally regarded the concept of self-esteem as meeting this need, our analysis suggests that this emphasis is too narrow because another concept of selfself-respecthas been ignored. Consider that the eld of psychology has focused on self-esteem and paid little attention to self-respect. Because psychologists have unwittingly emphasized the importance of self-esteem, a public self-esteem fallacy has developed (Baumeister

Constance Roland, Pennsylvania State University-Harrisburg, W157 Olmsted Building, Middletown, PA 17057 USA, email: croland@phc4.org

ISSN 0951-5089/print/ISSN 1465-394X/online/03/02024742 2003 Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/09515080320103355

248

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

et al., 1994; Dawes, 1994; Leary & Downs, 1995; Mruk, 1995). Indeed, many parents believe that if their children do not feel good about themselves (i.e., have high self-esteem), then they will be at risk for any number of emotional and psychological problems. Many therapists also have accepted the notion that if we could only enhance their self-esteem, then everything would be so much better (Mruk, 1995, p. 57). Pipher (1997, p. 158) suggested that in focusing on self-esteem instead of good character, therapists often fall into the trap of feeding narcissism. When clients are concerned mostly with massaging the self, they neglect the work that is necessary to build a solid foundation for meaningful personal change. The American educational system has also been affected by this fallacy as evidenced by the subordinating of its standards to the fostering of self-esteem independent of performance (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994, p. 432). Despite the fact that respect for self and others is necessary for stability and harmony within a society, there is little literature on self-respect or how it inuences the mental health of individuals and communities. This paper will attempt to (1) differentiate self-respect and self-esteem, (2) demonstrate the importance of selfrespect, and (3) explain the implications of the absence or presence of self-respect for individuals. It begins by tracing the role of self-respect in the development of Western civilization, continues by examining the development of the concept of self-esteem within the psychological community, and ends by evaluating the different contributions that self-respect and self-esteem make to individual functioning. 2. Philosophical approaches to self-respect The concept of self-respect has had signicant impact on the culture of Western civilization through literature and philosophy (Dillon, 1995). Authors of the great tragedies and epic poems of the classical era to twentieth century playwrights have woven tales of heroes who by a sudden stroke of fate dishonor themselves and lose their self-respect. This loss of self-respect dooms the heroes to fates worse than death unless they are able to redeem themselves by some heroic means. Philosophers have also discussed the moral signicance of self-respect. Terms such as magnanimity, proper pride, and a sense of dignity were an integral part of discussions by Aristotle, Aurelius, Augustine, Aquinas, Montaigne, Descartes, Pascal, Spinoza, Hobbes, Rousseau, Hume, Hegel, Mill, and Nietzsche (Dillon, 1995). However, it was Kant who rst placed the concept of self-respect into its central role in moral philosophy. Attempts to understand complex and elusive concepts, such as self-respect, are often aided by identifying the conceptual family to which a concept belongs (Dillon, 1995). Self-respect is considered to be a conceptual off-spring of respect, which allows its logical placement into the same conceptual family as dignity, regard, esteem, and honor because all are concerned with worth. Dignity derives directly from the Latin word for worth, regard is considered to be the recognition of the worth of an object, esteem is the appraisal of worth, and honor is described as the reward for great worth. Pride is an important related concept and helps to delineate

SELF-RESPECT

249

the differences between the closely intertwined concepts of self-respect and selfesteem. Indeed, Dillon (1995, p. 7) considered self-respect to be synonymous with pride because both are concerned with a sense of ones own dignity or a sense of personal dignity and worth. On the other hand, self-esteem, or a favorable opinion of oneself, appears more evaluative and may be identied with pride when it is overweening or inordinate. An advantage of identifying the concepts closely related to self-respect is that discussions related to it can be identied even if the term is not used. This is important in tracing the historical development of self-respect. The works of Aristotle, Hobbes, Hume, and Kant appear to have had a particularly signicant impact on contemporary understandings of self-respect and self-esteem (Dillon, 1995). Aristotles Nicomachean Ethics (1962) is the rst recorded systematic discussion of ethics in Western civilization (Denise et al., 1996). He believed that an essential dimension of the fully virtuous person was the proper appreciation of ones worth. Magnanimity, pride, and condent self-respect were to be found in such an individual. Aristotle contrasted this virtuous individual with the vain individual, who believed that he was more worthy than he was, and the unduly humble individual, who thought that he was less worthy than he was. Aristotle believed that what motivated virtuous conduct was an appropriate concern for self-knowledge, accurate judgment, and correct values rather than simply a good opinion of oneself (Dillon, 1995). The virtuous man, because he knew his own worth and maintained his worthiness, did not depend on the opinions of everyone and wished only to perpetuate his honor by being honored by those who also were virtuous. With Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, Kant introduced a new and still topical perspective to the concept of self-respect, namely, that all persons deserve respect, regardless of their character. His (1785/1967, p. 91) formulation, Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end, is considered by many philosophers to be the preeminent statement of the principle of respect for persons (Dillon, 1995, p. 14). This simple yet powerful idea, that everyone must be respected and that all persons should behave in ways that maintain that respect, is a major contribution to the understanding of self-respect. Kant proposed that because of their ability to rationalize, think, and choose, individuals have a moral duty to respect others and themselves, which requires them to act in certain ways and not in others. The foundation of Kants concept of self-respect was ones dignity as a person, which was also the foundation of all morality. Having self-respect carries the responsibility to only act in ways that reect ones status as a moral being. The duty of self-respect becomes the supreme moral duty, for it is a precondition of respecting others. In effect, there would be no moral duties if there were no duties to respect oneself. Pre-Kantian descriptions of the concept of self-respect (e.g., Aristotle, Hobbes, Hume) diverge into two lines of thought, the idea of respect as it pertains to the recognition of something important and the evaluation of the quality of something (Dillon, 1995). Kants writings joined these two lines of thought by dening two

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

250

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

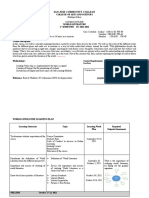

distinct grounds for the presence of self-respectthe person and the quality of the persons conduct. The writings of contemporary moral philosophers are grounded in these historical accounts of self-respect and can be categorized into four distinct groups (Dillon, 1995). One views self-respect as the proper appreciation of being a person (e.g., Boxhill, 1995; Hill, 1991; Thomas, 1995). A second treats self-respect as grounded in character and conduct (e.g., Downie & Teer, 1970; Rawls, 1995). A third argues that there are two kinds of self-respect (importance of personhood and quality of personhood) (e.g., Darwell, 1995; Massey, 1995). The fourth group (e.g., Meyers, 1995) does not differentiate between the importance and quality of personhood. Table 1 displays the differences and similarities between the views of both the historical and contemporary philosophers.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

3. Self-respect as appreciation of being a person The central argument for respect as proper appreciation of the importance of being a person is grounded in Kant. Thomas (1995) and Hill (1991) argued that individuals have two important duties that result from their status as rational beings. The rst is to respect the moral law that provides individuals with their rights, and the second is to respect the self by afrming ones moral rights in ones thought processes and behaviors. The fullling of these duties via thoughts and behavior is dependent upon certain beliefs and attitudes regarding oneself as a person, ones relationship with morality, and ones place in the moral community. Earlier, Sachs (1981) had suggested that such beliefs and attitudes translated into dispositions for certain actions and thoughts. Boxhill (1995) extended the importance of ones beliefs and attitudes by emphasizing that self-respecting persons must have condent conviction in their belief of their worth and rights. The self-respecting person responds to unjust treatment in calmly controlled ways that reveal inherent invulnerability of status as a person and belief in that status (Dillon, 1995, p. 23). Self-respect demands that persons protest the violation of their rights and that they do so within the boundaries of dignity. Another important aspect of the appreciation of the importance of being a person is the public availability of ones dignity (Meyer, 1989). Meyer also believed in the inherent worth of persons, although he suggested that while worth is not necessarily perceivable to others dignity is. Dignity is the way in which individuals visibly demonstrate their humanity and their worthiness of respect. It is how self-respect is displayed to others. To Kant, all humans had dignity by virtue of their capacity for rationality. Meyer pointed out that, while self-worth is inherent, it is possible that some individuals may be unable to express it and/or see it in others because of prejudiced views and insights. The inability to see anothers dignity is an affront to both the self-respect of the viewed and the viewer. To give meaning to their lives, it is important for people being oppressed to be able to display their dignity to their oppressors. Doing so will display the existence of dignity and cause the oppressors to view the oppressed with respect (Meyer, 1989). An example of the importance of visibly displaying dignity is found in Levis

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

TABLE 1. Historical and contemporary views of self-respect

(a) Historical Components of Self-respect

Theorist Self-knowledge; Accurate judgment Virtuous behavior Pride

Capacity for rationality Life plans guided by

Autonomous behavior

Subjective feelings toward self

Importance of others opinions If also virtuous Determined worth

Aristotle (trans. 1962) Hobbes (1651/1965) Hume (1739/1965) Kant (1785/1967) Self-survey Principal of respect for persons Pride Continual competition with others for honor What is good for humanity Moral law

Dignity

Reverence: humility and pride

Declare pride as appropriate Worthy of admiring respect of others

SELF-RESPECT

251

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

252

(b) Contemporary Group I (appreciation of being a person) Components of Self-respect

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Theorist Respect moral law

Capacity for rationality Life plans guided by

Autonomous behavior

Subjective feelings toward self

Importance of others opinions

Thomas (1995) & Hill (1991) Sachs (1981) Conviction in worth Public availability of dignity

Dignity

Dignity

Afrm rights in thought & behavior Dispositions for thoughts and actions

Emotion: indignation or resentment

Boxhill (1995) Meyer (1989)

Dignity Dignity

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

(c) Contemporary Group II (character and conduct) Components of Self-respect

Theorist Conative selfrespect objective standards Protect self from intolerable treatment

Capacity for rationality Life plans guided by

Autonomous behavior

Subjective feelings toward self Estimative self-respect favorable opinion of self Self-denition vs. execution of selfdened values

Importance of others opinions

Downie & Teer (1970)

Taylor (1995)

Objective standard of autonomy; Subjective standard set for self Standards based on what has value in own life

SELF-RESPECT

253

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

254

(d) Contemporary Group III (importance of personhood and quality of personhood) Components of Self-respect

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Theorist Expect respect; Unwilling to tolerate disrespect Moral component: beliefs and conduct meet objective criteria Objective standards of worthy conduct

Capacity for rationality Life plans guided by

Autonomous behavior

Subjective feelings toward self

Importance of others opinions

Darwell (1995)

Recognition selfrespect

Massey (1995)

Dignity

Appraisal self-respect grounded in excellence of character Psychological component: favorable self-regarding beliefs, attitudes and feelings

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

(e) Contemporary Group IV (unied account of self-respect) Components of Self-respect

Theorist Exercise moral autonomy Triadic relationship: attitude, behavior and object

Capacity for rationality Life plans guided by

Autonomous behavior

Subjective feelings toward self

Importance of others opinions

Meyers (1995)

Self-concept Theorist James (1890/1952)

Evaluation successes vs. pretensions Looking-glass self Generalized other

Cooley (1902/1956) Mead (1934/1967)

SELF-RESPECT

255

256

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

(1986) memoir of a Nazi death camp, wherein the Nazis purpose was not death of the prisoners, but rather the annihilation of dignity. Prisoners were subject to what DesPres (1976) termed excremental assault, i.e., a systematic subjection to lth. They were forced to spend their days in excrement, to sleep and work in it, to remain covered in it, even at times to eat or drink it. The goal was to destroy the prisoners sense of humanity. To survive, it was necessary to hold onto ones dignity by trying to remain visibly human. According to Levi, efforts to be clean were often the only opportunity prisoners had to express their self-respect and maintain their dignity. Unfortunately, the Nazi death camps are only one of several historical and current examples of the vulnerability of self-respect to the attitudes and treatment of others. Fortunately, counter examples exist (Dillon, 1995). Benevolence, kindness, generosity, and compassion are all virtues that nourish and maintain the self-respect of the giver and the receiver.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

4. Self-respect as grounded in character and conduct The second group of contemporary philosophers, who treat self-respect as grounded in character and conduct, followed Aristotle and Hume by suggesting that selfrespect entails more than just being a person. In order to possess and maintain self-respect, one must also be self-aware. Within this context, Downie & Teer (1970) dened two kinds of self-respect: conative and estimative. Conative selfrespect follows in the Aristotelian tradition by suggesting that self-respect is a motivational character trait. A concern for dignity causes one to refrain from behavior that is unworthy and motivates behavior that meets both objective and subjective standards of what is moral and worthy. Hill (1991) developed this idea further by stating that autonomy is exercised by developing and committing to a set of personal standards for conduct and character that are central to ones self-conception. The second form of self-respect discussed by Downie & Teer (1970) is merit-based and called estimative self-respect. This form of self-respect ts Humes view and is described as a favorable opinion of oneself. This opinion, which is grounded in ones conduct and character, is spawned by the belief that one has met the standards that one should meet. Taylor (1995) dened self-respect as having a favorable opinion of oneself that motivates self-protection from treatment or behavior that is intolerable. Although Taylor agreed with Boxhill (1995) that self-respect demands behavior that protests attacks on ones worthiness, they differed on the source. For Boxhill, the sole source of self-respect was personhood, whereas for Taylor it was the congruence between ones self-denition and ones execution of self-dened values. Taylor suggested that the expectations or standards for the self-respecting persons behavior are grounded in what has value for the life one wants to lead. Self-respect is especially grounded in the values from which ones normative identity derived. Respecting the self means living in accordance with ones own standards and expectations. Because it is necessary to live with ones values in order to have integrity, self-respect serves to preserve ones integrity and identity. Shame also operates to preserve integrity and identity. It is a protective emotion that is experienced if one violates ones standards

SELF-RESPECT

257

and expectations (Taylor, 1995). Although shame may be considered as damaging to self-respect, experiencing it ensures that self-respect still exists. Individuals cannot experience shame unless they still value the code that underlies their self-respect. Taylor felt that individuals who experience shame are still aware of and value their standards and hence can regain self-respect. 5. Two kinds of self-respect: recognition and appraisal A third group of contemporary philosophers argue that the issue is not what self-respect is, but rather that there are different kinds. Darwell (1995) proposed two different kinds of self-respect, recognition and appraisal. Recognition self-respect is the regard that all persons are entitled to have. It is derived from the writings of Kant and supported by our earlier discussions of Boxhill (1995), Hill (1991), and Downie & Teers (1970) notion of conative self-respect. Recognition self-respect motivates the individual to engage in worthy conduct, to eschew unworthy conduct, expect respect from others, and to not tolerate disrespect. Appraisal self-respect refers to the positive appraisal of oneself as a person (Darwell, 1995). It is meritbased and grounded in the excellence of ones character. It was considered by Aristotle and Hume and discussed earlier in Downie & Teers (1970) discussion of estimative self-respect. Massey (1995) proposed that self-respect had two important components: a psychological or subjective one and an objective or moral one. The psychological or subjective component is both necessary and sufcient for an individual to have favorable self-regarding beliefs, attitudes, and feelings. The self-respecting persons favorable attitude is grounded in morally appropriate ways because it is important to both value ones moral status as having basic rights and to possess a character that is truly good. 6. A unied account of self-respect Meyers (1995) represents the fourth and nal perspective and proposed a unied account of self-respect. She suggested that there is a triadic relationship among attitude, behavior and object. Self-respect exists when the relationship between the triads components is unqualied and uncompromised such that there is a respectful attitude expressed through respectful behavior toward an object that is worthy of respect. If any element of the triad is inappropriate, self-respect is compromised in either an indecent or innocent manner. Indecent compromise occurs if individuals knowingly respect themselves for conduct they know is immoral. Innocent compromise occurs when individuals know that everyone has dignity and respect, but, because of social conditioning, believe themselves to have less. Only uncompromised respect has the intrinsic goodness of self-respect. Meyers suggested that the resultant correspondence between attitude and self-worth leads to uncompromised self-respect, which because of its greater stability, has increased value when individuals strive to meet their self-dened values and life plans. In summary, several themes run consistently through both historical and

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

258

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

contemporary philosophical literature. Self-respect exists on a variety of levels and each carries its own implications. Self-respect based on ones capacity for rationality leads to behaviors that promote autonomy, such as independence, self-survey, self-control, and tenacity. Self-respect also demands behaviors that display a condent conviction that one should be treated with respect. Finally, self-respect requires the development and pursuit of personal standards and life plans that are guided by the moral law of respect for self and others. Motivation to engage in self-respecting behaviors occurs through the desire to sustain the emotions of reverence towards oneself, pride in ones actions, and condence in ones life plan. Although the opinions of others can help to sustain the subjective feelings that result from actions that are congruent with self-respect, these opinions are only relevant when these individuals are also engaged in respectful behaviors and attitudes.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

7. Psychological theories of self-esteem Dillons (1995) review of the contemporary discussions of self-respect revealed that while philosophers speak of self-respect, psychologists discuss self-esteem. A computer search of PsychINFO (1984 to February 2001) using the term self-respect resulted in 150 abstracts, whereas the term self-esteem resulted in 13,811. These gures suggested either that the two terms were not being differentiated, or that self-respect was given little attention; the latter possibility seems more likely. One reason why is that modern theories of self-esteem are grounded in historical psychological theories of self-concept rather than historical discussions of self-respect. Thus, the self-concept theorizing of James (1890/1952), Cooley (1902/1956), and Mead (1934/1967) laid the foundation for the development of self-esteem theory from a psychological perspective. James is generally recognized as the rst psychologist to develop a theory of self-concept (Marsh et al., 1992). Self-esteem and the social self were two important components of his theory. He dened self-esteem as a ratio of ones successes to ones pretensions or the value that an individual places on successes in a particular activity or attribute. Another important theoretical component was the social self. This component highlighted the importance of the evaluations of others to the development of an individuals self-concept. The social self became an important part of the self-concept theories espoused by Mead (1934/1967) and Cooley (1902/1956). Cooley (1902/1956) believed that ones self-concept derived from the attitudes of signicant others. He postulated that individuals are motivated to assess the attitudes of signicant others towards them. Cooley referred to this phenomenon as the looking-glass self. This formulation is very similar to Meads (1934/1967) concept of the generalized other. Mead postulated that self-concept was dependent, to a large extent, on the pooled or collective judgments of signicant others towards the individual. Self-concept continued to be the focus of considerable research and theorizing

SELF-RESPECT

259

(Backman et al., 1982). Wylie (1979) examined over 4,500 references for her review of the self-concept literature. She found that the vast majority of self-concept discussions were limited to just one of its components, global self-esteem. Rosenberg & Kaplan (1982, p. 2) recognized the increasing awareness in the literature of the complexity of self-concept and its constituents, e.g., self-esteem. To them, selfconcept should be viewed as the totality of the individuals thoughts and feelings with reference to himself or herself as an object. In this formulation, self-esteem functions as a dimension and as a primary motive. Dimensions are considered to be abstract qualities that characterize either self-concept as a whole or its specic components and how one thinks and feels about oneself. Self-esteem is the dimension of self-concept that addresses whether one accepts, respects, and considers oneself worthwhile. Motives were described as impulses to act in the interest of self-concept (Rosenberg & Kaplan, 1982). Self-esteem was considered to be the most prominent and possibly the most powerful self-concept motive. Kaplan (1982) also discussed four categories of empirical observations regarding the prevalence of the self-esteem motive. One was that individuals tend to describe themselves in positive terms. Another was the tendency for individuals with low self-esteem to employ behaviors that were self-enhancing and self-defensive. The third was that those with low self-esteem manifest subjective distress. The nal observation was that individuals with positive self-attitudes maintain them, while those with negative self-attitudes change them in a more positive direction. In our attempt to differentiate self-respect and self-esteem, it is important to note the place that morality held in Rosenberg & Kaplans (1982) notion of self-concept. Gordon (1982) assists in this regard because he developed 30 broad categories with which to classify responses to the question, Who am I? A category separate from self-esteem was termed A Sense of Moral Worth and dened as a sensed degree of adherence to a valued code of moral standards that transcended the self. In effect, individuals evaluate their own attributes and actions in terms of the moral standards of their culture and through this process they have a continuing sense of greater or less moral worth (Gordon, 1982, p. 17). Even though the concept of self-esteem evolved as a component of self-concept theory, it has become pervasive in the social sciences. Both the 4,500 articles reviewed by Wylie (1979) and the 13,811 references found in the psychological literature since 1984 conrm the continued widespread interest in self-esteem. Although the terms self-concept and self-esteem have been used interchangeably, Hart & Edelstein (1992) suggested that a distinction should be made. Self-concept should be used in reference to the cognitive process in which a description of oneself is developed and maintained, whereas self-esteem should be used to denote an affective process that evaluates ones self-description (Brinthaupt & Erwin, 1992). This process of self-evaluationself-esteemhas been viewed as a key to understanding normal, abnormal, and optimal behavior (Bednar et al., 1989; Markus & Wurf, 1987; Wells & Marwell, 1976). Furthermore, connections have been made between self-esteem and social problems such as substance abuse, teen pregnancies, school drop-out rates, and delinquency (Mecca et al., 1989). The practical implica-

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

260

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

tions of self-esteem to individual mental health included assumptions that it was related to positive mental health (Bean, 1992; Steffenhagen, 1990). Relationships were suggested to exist between higher levels of self-esteem and high ego functioning, personal adjustment, internal control, favorable therapy outcomes, positive adjustment to old age, and autonomy (Bednar et al., 1989). Conversely, a lack of self-esteem has been suggested to be related to negative outcomes, including some mental disorders. As early as 1959 it was noted that those who seek psychological help are often suffering from feelings of unworthiness, inadequacy, and anxiety (Coopersmith, 1967). A number of studies suggested that low self-esteem was a correlate or risk factor for both depression and suicide (e.g., Brage & Meredith, 1994; DeMan & Leduc, 1995; Harter et al., 1992; Marciano & Kazdin, 1994). These studies suggested the importance of self-esteem, but were unclear regarding its specic role in exacerbating conditions that may lead to depression and/or suicide. The research of Coopersmith (1967), Rosenberg (1979), Harter (1986, 1990a, 1990b, 1993) and Harter & Jackson (1993) has been inuential in dening the concept of self-esteem, although its role remained unclear. These researchers agreed with earlier theorists (e.g., Cooley, James, Mead) that self-esteem was either a positive or negative evaluation of ones worthiness. They disagreed, though, concerning the processes individuals used to arrive at expressed levels of self-esteem. Harter (1990b) suggested that this evaluative process can be explained by a unidimensional (e.g., Coopersmith, 1967; Rosenberg, 1979) or multidimensional model (e.g., Harter, 1990b). An examination of the differences and similarities between the most popular measures of self-esteem reveals these two differing processes and helps to answer our earlier question of whether or not the self-esteem literature is addressing the concept of self-respect (see Table 2).

8. Unidimensional models The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (1967) and the Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale (1969) were the prevailing models for self-esteem assessment in the in late 1960s (Harter, 1990b). Both are unidimensional measures because self-esteem is considered to be a unitary concept. A single score is calculated by summing the responses across a range of content areas. This score should reect an individuals sense of self-esteem across various life areas. The Piers-Harris scale (1969) asks respondents to comment on what they do and do not like about themselves within six different areas: behavior, intellectual and school status, physical appearance, anxiety, popularity, and happiness/satisfaction. The Coopersmith scale (1967) taps self-attitudes across four areas: peers, parents, school, and personal interests. Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Scale (1979) also is based on the unidimensional model. It remains one of the most widely used measurements of self-esteem (Hagborg, 1993). Rather than arriving at a score that is an aggregate of items from separate domains, this scale taps self-esteem directly via respondent evaluations of 10 statements such as I have a number of good qualities (Rosenberg, 1979).

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

TABLE 2. Measures for self-esteem Content of subscales Calculation of scores Basis of self-esteem

Measure

Unidimensional models Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (1967) Peers, parents, school, personal interests Sum of all responses Sum of all responses

Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale (1969) Sum of all responses

Rosenberg s Self-Esteem Scale (1979)

Behavior, intellect/school status, physical appearance, anxiety, popularity, happiness and satisfaction Does not address separate domains. 10 questions tap self-esteem directly: i.e. I am satised with my life, I think I am a failure.

Self-evaluation of capacities, performance and peception of others opinions Self-evaluation of capacities, performance and perception of others opinions Self-evaluation of capacities, performance and perception of others opinions

Multidimensional models Harters Self-Perception Prole for Children (1985) Five competence domains: scholastic, athletic, social acceptance, physical appearance, behavioral conduct. Global self-worth

Self-evaluation of capacities, performance and perception of others opinions

SELF-RESPECT

Marshs Self-Description Questionnaire (1984)

Seven separate domains: scholastic, math, reading, physical, peer, parent. General self-worth

Scores for each domain and for global scale are summed separately. Attempt to evaluate how domains are weighted and combined to produce global self-worth Scores for each domain are summed separately. Global score is sum of domain scores.

Self-evaluation of capacities, performance and perception of others opinions

261

262

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

9. Multidimensional models The multidimensional models have developed in response to the concern that unidimensional models masked important evaluative distinctions that individuals made regarding their prociency in different domains of their lives (Harter, 1990b). Harters Self-Perception Prole for Children (1985) and Marshs Self-Description Questionnaire (Marsh et al., 1984) are two multidimensional scales with considerable empirical support (Harter, 1990b). Both evaluate competence or self-evaluation across specic domains such as scholastics, athletics, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct as well as on a scale that evaluates an overall or global sense of self-worth. Although there had been much self-esteem research by the late eighties, many questions remained regarding its determinants, consequences, and contribution to individual functioning (Harter, 1990a). To explore them, Harter (1990a) incorporated both the unidimensional and the multidimensional models so that all aspects of the theoretical development of the self-esteem construct were represented. The initial phase relied on the contributions of James (1890/1952) and Cooley (1902/ 1956), and the unidimensional model of self-esteem in the Coopersmith (1967), Piers-Harris (1969), and Rosenberg (1979) scales. This phase investigated whether the ratio of competencies and pretensions or the opinions of signicant others had a greater impact on global self-esteem. The study was conducted across the life span with elementary- and middle-school age children, adolescents, college students, and adults. Harter (1990a) found that for all age groups, except college students, competency ratios and the regard of signicant others contributed about equally to global self-esteem. For the college age group, the competency ratio had more impact than the regard of signicant others. Across all age groups perception of ones physical appearance was a better predictor of self-esteem than any other competency domain. Social acceptance was the second best predictor of global self-esteem. Parents and peers were equivalent signicant others for elementary, middle school, and adolescent groups, whereas peers were the most signicant for college students. The ndings for adults differed slightly in that intimate relationships were a slightly better predictor than the regard of others. The signicant others for the adult group were represented by religious groups, civic activities, and coworkers. The above review of what the most frequently used self-esteem measures actually measured and reported revealed that self-esteem measurements evaluate how one feels about ones capacities, performance, and perception of others opinions. Self-esteem is considered to be an emotional response to self-evaluation and is often discussed in terms of liking or feeling good about oneself. Although, the desire to feel good is often motivationally valuable, individuals who focus on maintaining or enhancing this positive affect of self-esteem may not be objectively evaluating their responses. Sometimes the quest to feel good results in dysfunctional or dangerous behaviors (Baumeister, 1991; Mecca et al., 1989). Leary & Downs (1995, p. 139) suggested that if individuals do not engage in an adequate conscious and rational assessment of the consequences of engaging in such behaviors,

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

SELF-RESPECT

263

they may attempt to maintain self-esteem at a personal cost. Their sociometer hypothesis explained this phenomenon. Leary & Downs (1995) reported that even though there has been a great deal of attention to the behaviors that result from the accepted motives of self-esteem, the basic questions of source and function have not been adequately addressed. They suggested that if the function of self-esteem could be adequately explained, then answers could be found to important questions, such as why individuals need to maintain or in some instances enhance their self-esteem, why negative affect is associated with lowered self-esteem, and why individuals tend to behave in ways that protect and enhance self-esteem, even when these behaviors are detrimental. Their proposed answer is found in the sociometer hypothesis (Leary 1999; Leary & Downs, 1995; Leary et al., 1995), which posited that the self-esteem system evolved as a means of maintaining interpersonal relationships. It should be noted that during the past decade other researchers have also been investigating the function of self-esteem in psychology. For example the theory of terror management (Greenberg et al., 1997) proposes that self-esteem is a buffer against the anxiety that is caused by the awareness of ones mortality. Leary (1999) described the self-esteem system as a subjective indicator or gauge that is designed to monitor the quality of personal relationships. The sociometer hypothesis subscribed to the multidimensional model of self-esteem, where trait self-esteem referred to an average level of self-esteem and state self-esteem referred to the uctuations in self-esteem that occurred during the course of daily living (Leary et al., 1995). Upward changes in state self-esteem signal an improvement in the degree to which one is being socially included or accepted by other people, whereas downward changes in state self-esteem signal a deterioration in the degree to which one is being included or accepted (Leary, 1999, p. 208). The importance of social groups to the survival and reproduction of the human species is a universally accepted theory (e.g., Ainsworth, 1989; Barash, 1977; Baumeister & Tice, 1990; Bowlby, 1969). Given this inherent need for social acceptance, the sociometer hypothesis suggested that the self-esteem system developed as a means to monitor others response to us. At a pre-attentive level, the system continuously monitors others responses for cues that indicate disinterest, disapproval, avoidance, or rejection. When any of these or similar cues are noted, the system responds with negative self-relevant affect (a loss in self-esteem) that motivates us to behave in ways that should increase our acceptance (Leary, 1990; Leary & Downs, 1995; Leary, 1999). The four central predictions that derive from this perspective of the self-esteem system are as follows: (1) events that threaten self-esteem increase the likelihood of social exclusion, (2) exclusion and rejection result in lower state self-esteem, (3) an association exists between low trait self-esteem and a generalized expectancy of rejection, and (4) approval seeking behaviors are motivated by rejection (Leary & Downs, 1995) [1]. Using the sociometer hypothesis as a basis for understanding the self-esteem system, Leary (1999, p. 216) suggested the following revisions to the three major assumptions that pervaded the self-esteem literature:

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

264 (1)

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

(2)

(3)

Human beings are motivated to preserve, protect, and occasionally, enhance the degree to which they are accepted, included, and valued by other people. The self-esteem system is involved in the process of monitoring and regulating peoples social acceptance. The psychological benets of low and high self-esteem derive from the fact that both self-esteem and psychological benets are associated with perceived social acceptance. Raising low self-esteem improves psychological well-being and produces desirable changes in peoples behavior because interventions that raise self-esteem promote a sense of social inclusion. It is this sense of being acceptednot self-esteem per sethat produces desirable effects.

Examining Learys revised assumptions and explanation of the self-esteem system led Kirkpatrick & Ellis (2001) to expand the sociometer hypothesis. They suggested that the problems of social inclusion vary according to domain. Inclusion criteria may be driven by the differences in relationships between individuals and their mates, families, and various peer groups. Each of these adaptive problems requires its own sociometer, such that an individuals behavior is guided by multiple sociometers that not only distinguish between the inclusion criteria of specic domains, but also recognize the adaptive value of the individuals acceptance by a particular person or group. Leary (1999) pointed out that the sociometer hypothesis offered a new perspective to the social and psychological importance of self-esteem. Socially, self-esteem maintains interpersonal relationships by alerting us to potential rejection and motivating us to engage in behaviors that will increase inclusionary status. Psychologically, self-esteem is important because social acceptance promotes psychological wellbeing. Leary & Downs (1995), as well as others (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1994; Dawes, 1994; Mruk, 1995; Pipher, 1997), have raised concerns regarding the popularization of self-esteem theory and the persistent public belief that the development of high self-esteem is the solution for individual and societal dysfunction. In his review of self-esteem theory, Mruk (1995) found that a public self-esteem fallacy has developed such that many parents believe that without high self-esteem their children will be at risk of emotional and psychological problems. In a review and research on self-regulation, Baumeister et al. (1994, p. 5) suggested that rather than suffering from low self-esteem, America is suffering from a spreading epidemic of selfregulation failure. Dawes (1994) report on psychotherapy suggested that many mental health professionals, whose treatment protocols are based on intuitive understanding rather than on empirical evidence, have perpetuated the belief that self-esteem is a causal variable of behavior. Such beliefs were bolstered by the publication of the California Task Force on the Importance of Self-esteem, which, in 1986, embarked on a major effort to prove scientically that low self-esteem was a causal factor in the behaviors that become social problems. We all know this to be true, and it is not really necessary to create a special California task force on the subject to convince us. The real problem we

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

SELF-RESPECT

265

must address is how we can determine that it is scientically true (Smelser, 1989, p. 8). The task force reviewed several thousand studies and journal articles, yet they were unable to nd more than a weak correlation between behavior and self-esteem, e.g., associations between self-esteem and its expected consequences are mixed, insignicant, or absent (Smelser, 1989, p. 15). Nevertheless, the task force continued to argue for programs designed to increase self-esteem. Accompanying the belief that low-self esteem causes emotional distress and dysfunctional behavior was the belief that high self-esteem is related to optimal mental health. Its general importance to a full spectrum of effective human behaviors remains virtually uncontested (Bednar et al., 1989, p. 1). Branden (1994) claimed that the likelihood of treating others with respect, kindness, and generosity increased as self-esteem increased. Mecca et al. (1989) identied self-esteem as a causal factor in personal and social responsibility. However, the belief in high self-esteem as a panacea for emotional and psychological dysfunction has begun to lose its luster in peer-reviewed literature. This change resulted from the lack of scientic evidence supporting contentions that low self-esteem leads to negative outcomes and that high self-esteem leads to positive outcomes, as well as the accumulating empirical evidence that high self-esteem does not necessarily lead to positive or desirable behaviors. Self-serving attributions, a strategy often employed to increase self-esteem, can create social difculties when others realize that this tactic is being employed (Forysth et al., 1981). When their egos were threatened, high self-esteem individuals allowed self-enhancing illusions to affect decision processes and committed themselves to goals they were unable to meet (Baumeister et al., 1993). High self-esteem has been related to non-productive persistence (McFarlin et al., 1984). There is also an association between excessively high self-esteem and such dysfunctional and undesirable behaviors as childhood bullying (Olweus, 1994), rape (Scully, 1991), and violence in youth and adult gangs (Jankowski, 1991). A multidisciplinary review of studies related to aggression, violence, and crime conducted by Baumeister et al. (1996, p. 5) found that violence appears to be most commonly a result of threatened egotismthat is highly favorable views of self that are disputed by some person or some circumstance, and added that atrocities have been perpetuated against humanity by those who, because of their sense of superiority, believed they had the right to manipulate, dominate, and harm others. Although separate bodies of literature devoted to the understanding of self-esteem and aggression have been developed over the years, it is only recently that psychologists have undertaken efforts to understand the relationship between these two phenomena (e.g., Bushman, & Baumeister, 1998; Kirkpatrick et al., 2002; McGregor et al., 1998). As this review demonstrates, efforts to understand self-esteem continue. One of the most promising avenues for determining the importance of self-esteem is provided by Leary & Downs (1995) sociometer hypothesis because it examines the source and function of self-esteem. Thus the continuation of research related to the sociometer hypothesis should be important in clarifying the role of self-esteem in individual and societal functioning.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

266

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Discussion Our review of self-respect and self-esteem suggested several differences. First, the literature regarding self-respect is grounded in philosophical discussions and is often discussed in relation to morality, while self-esteem literature developed from and then dominated the psychological discussions of self-concept. Second, central to the denition of self-respect was the existence of a dened moral code that clearly stated the importance of behaving in ways that treat the self and others as worthwhile entities, rather than simply as a means to an end. In contrast, the personal evaluation of ones successes and the opinions of others that were central to the denition of self-esteem were not subject to a particular moral code. Instead, the moral code that accompanied how individuals valued their choices was entirely within their discretion. This suggests the third difference; namely, that the objective components of self-respect are predened, whereas those of self-esteem are not. These distinctions lead to two conclusions: (1) the relationship between self-respect and self-esteem is worthy of study, and (2) the importance of self-respect to psychological functioning requires separate evaluation and discussion.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

10. Self-respect and self-esteem: more than a difference in terminology? Why did the psychological literature become focused on self-esteem rather than self-respect, given the ubiquitousness of the term self-respect in the philosophical literature and the evolution of psychological concepts from philosophical roots? Are self-esteem and self-respect considered to be different concepts? Or, if they are considered to be synonymous, then how did the public and psychological communities conception of self-esteem become focused on the importance of feeling good and ignore the development of self-respect? To answer these questions we must revisit the basic tenets of self-respect discussed earlierthe role of rationality in human dignity, the importance of autonomous behaviors, the importance of personal standards and life plans that not only advance ones own aspirations, but are also based on law of respect for persons. We shall look closely at both meaning and language. According to Kant, it was human rationality that provided for equal dignity among humans and was the basis for the law of respect for persons. It is the human capacity for rational thought that allows us to realize our inherent worth, and provides us with the ability to display that worth by making choices that consider the consequences of our actions for ourselves and others. Appreciating the capacity for rationality is demonstrated through treatment of the self and others as worthwhile entities by virtue of ones existence and subjectively experienced through feelings of dignity. Rationality is also present in models of self-esteem. Individuals are encouraged to evaluate their options and choose wisely their course of action. Yet, it is the personal evaluation of capacities and successes and the perceptions of others opinions that leads to the emotional experience of either feeling good or bad. Conversely, the basis of self-respect is the acceptance of ones worth as a fact or a given.

SELF-RESPECT

267

Personal autonomy follows this acceptance and provides the power to respect ones self and have the personal standards and personal life plans that give meaning to life while respecting others. As with rationality, these tenets are found in models of self-esteem, but in contrast to self-respect, appear to reside in the individuals intent. Individuals experience a loss of self-esteem when their self-evaluation reveals that they have not achieved success or acceptance by a particular social group. If increasing self-esteem is the sole motivation for behavior, one may respond to this self-evaluation by acting in ways that achieve success or increase acceptance without regard to the law of respect for persons. Yet if one is committed to the principles of self-respect, the knowledge that one has inherent worth and is living his or her life in a manner that honors that worth in oneself and others would provide for the positive feelings related to self-respect and the motivation to continue self-respecting behaviors. The above comparison demonstrates the differences in interpretation of the tenets of self-respect. Rationality and autonomy did remain part of self-esteem discussions, while the law of respect for persons did not. A closer look at the language of both historical and contemporary philosophers may explain why. The two words rationality and morality appear consistently throughout philosophical writings. Regarding rationality, discussions of both self-respect and self-esteem acknowledge the importance of the ability to think and choose a course of action. Regarding morality, as discussed earlier, Pipher (1997) suggested that, in the 1970s, many psychologists determined that the prescription of moral behavior was outside their roles. Perhaps not surprisingly, this time frame coincides with the beginning of a marked increase in the number of publications in PsychINFO with self-esteem in their title (Jacobson, 2000). Recall also that while philosophical discussions of self-respect were oriented to the reciprocation of individual behavior and cultural development, the psychological concept of self-esteem evolved from self-concept, which was focused on individuals perceptions. Perhaps psychologists abandoned self-respect and chose self-esteem because philosophers were discussing self-respect in terms that some psychologists regarded as negative. Also, self-esteem was studied as a component of self-concept. Simply put, psychology would become increasingly oriented to the needs of the individual expressed by personal evaluations based on the evaluations of others opinions, and less focused on the role that this individuality played in the development of society. The declaration that feeling good would lead to optimal mental health and protect one from emotional or mental dysfunction, provided the populace with a simple focusensure that everyone feels good all of the time. As discussed previously, there were concerns in the psychological community (e.g. Baumeister et al., 1994; Leary, 1999; Mruk, 1995) regarding the notion of self-esteem as a panacea for individual and societal ills. One outcome was the development of the sociometer hypothesis (e.g., Leary, 1999) which explained ones experiences of positive and negative affect (high and low self-esteem) and their relationship to ones perceived inclusion or exclusion from social groups. Recall that Leary & Downs (1995) emphasized the importance of considering the consequences of behavior that would increase feelings of acceptance. We suggest that self-respect

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

268

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

motivates individuals to consider consequences and engage in another important aspect of human nature and a major developmental taskbalancing the need to connect with others and the need to maintain independence and autonomy (Lorenz, 1987; Zahn-Waxler & Radke-Yarrow, 1990). Is it possible that aversion to the word morality contributed to the proliferation of psychological literature that popularized the importance of an autonomy geared towards feeling good and overshadowed the importance of another essential human characteristic, empathy? Empathy and prosocial behavior are inherent aspects of human nature and cannot be ignored. It may be that making a distinction between self-esteem and self-respect will enhance the study of human nature by allowing theorists and researchers to focus on the effects of perceived inclusion or exclusion, as well as the processes of balancing our innate tendencies for prosocial behavior and autonomy. Understanding these two processes and their interactions should lead to a better understanding of the relationship between self-esteem and self-respect. We propose that a relationship exists between self-respect and self-esteem such that self-respecting individuals may experience either high or low levels of selfesteem and individuals with high levels of self-esteem may or may not possess self-respect. This would explain the spectral differences (i.e., violent vs. nurturing) found in the behaviors of individuals reporting high levels of self-esteem. This relationship may also account for the lack of conclusive evidence supporting the contention that those who report low levels of self-esteem will suffer from emotional or psychological dysfunction. Recall that the sociometer hypothesis contended that the function of the self-esteem system is to continuously monitor inclusionary status and notify the individual when that status is threatened. Given that social groups were crucial for protection and reproduction (Barash, 1977), this function of self-esteem is easily understood. What is less easily understood is the wide range of pro and antisocial behaviors displayed by individuals who demonstrated high self-esteem on accepted psychological measures. Although violent individuals have demonstrated high levels of self-esteem, everyone with high self-esteem levels is not violent. Even though non-productive persistence occurs in individuals with high self-esteem levels, all individuals with high self-esteem do not engage in non-productive persistence. Conversely, there is no empirical evidence that individuals demonstrating low self-esteem are at a signicantly greater risk of emotional or psychological difculties than individuals with moderate or high self-esteem levels. This lack of consistency between levels of self-esteem and resulting behaviors suggests the presence of an unidentied mediating factor. We propose that self-respect, rather than being a synonym for self-esteem, is the unidentied mediating factor that accounts for the differences in how either low or high self-esteem is emotionally experienced and behaviorally expressed. 11. Self-respect and self-esteem: affect and behavior The literature reviewed suggests several differences in how self-respect and self-esteem impact individual functioning. A comparison of the interactions between

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

SELF-RESPECT

269

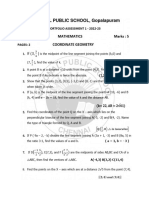

cognition, affect, and behavior demonstrates these differences (see Figure 1). As noted above, the presence of a particular moral code within a system of self-respect dominates its objective components. Consider that self-esteem may be somewhat more subjective in nature, not only because evaluations are based on differing criteria, but also because affect is regarded to be its predominate property. As discussed earlier, there is agreement among theorists that self-esteem is an attitude, specically an attitude about oneself derived from personal evaluations of the self and perceptions of others opinions (e.g., Coopersmith, 1967; Rosenberg, 1979; Harter, 1990b). Attitudes can develop from any of the three components, cognition, affect, or behavior (Edwards, 1990). Drawing on early theorists (e.g., James, 1890/1952; Mead, 1934/1967), as well as more recent ones (e.g., Rogers, 1959; Kagan, 1989; Watson & Clark, 1984), Brown (1993) has persuasively argued that self-esteem was grounded in affective rather than cognitive processes, and that feelings are most important to individuals. Hence, individuals do not just think positive or negative thoughts about themselves, they feel good or bad about themselves. The sociometer hypothesis (Leary & Downs, 1995; Leary et al., 1995; Leary, 1999) claried the central role of affect in self-esteem. It is the negative or positive affect that is described as low or high self-esteem that provides ongoing feedback to individuals regarding their potential inclusion or exclusion from a particular social group. Because this monitoring often occurs at a preconscious level, cognition may not play a role until a threat is perceived. When threats to an individuals inclusionary status are noted, the individuals attention is turned towards the self. The individual is then motivated to behave in ways that will increase the potential for inclusion by that social group. Behaviors may occur without serious thought as to their potential consequences. On the other hand, cognition and the law of respect for persons would be considered the predominate properties of self-respect. The central tenet of self-respect is the understanding and consideration of mans humanity, which then extends to the duty to treat the self and others in a manner that honors that humanity. Specically, it requires treating the self and others as an end, never as a means. To do so, one has to think carefully about what is important to oneself and others. Individuals have to think of themselves and others outside of the experience of the moment and determine if ones actions will be in concordance with ones values, move one closer to the realization of predened objectives and goals, and also demonstrate respect for the self and for others. Simply put, it means considering the consequences of ones actions before performing them. Feelings, such as pride and condence, when one has chosen the correct course of action, or shame or guilt, when one has chosen the incorrect course of action, motivate one to continue the processes related to self-respect. According to the sociometer hypothesis, behaviors motivated by self-esteem may be performed with minimal or no consideration when they are guided by the immediate desire to achieve social inclusion. By denition, behaviors motivated by self-respect consider the law of respect for persons and are not subject to inclusionary needs. This does not mean that individuals acting from the tenets of self-respect may not act without stopping to think. Many respectful behaviors, such as manners or listening carefully to others, are learned, incorporated

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

270

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

FIG. 1. Proposed models for interaction of cognition, affect, and behavior of self-respect and self-esteem.

SELF-RESPECT

271

into ones repertoire, and then performed automatically. The crucial difference here is that if individuals possessing self-respect detect cues of rejection, they will not abandon self-respecting behaviors in order to meet inclusionary needs. On the other hand, individuals lacking self-respect may behave in ways that violate the law of respect in order to meet their inclusionary needs and experience positive levels of self-esteem. 12. Self-respect: importance to individual and societal functioning. The philosophical literature reviewed earlier clearly supports the importance of self-respect to individual and societal functioning. Support also exists in the theoretical discussions and empirical evidence of existing psychological literature, even though the term or concept of self-respect, as dened herein, is rarely used. A closer look at how the differences described above between self-respect and self-esteem impact functioning on a daily basis demonstrates existing support within the psychological community for the tenets of self-respect. Consider the following: (1) self-esteem is important to individual functioning, and (2) the level of esteem that individuals hold for themselves is determined by the number of successes they have experienced (e.g., experiencing inclusion as dened by Leary and his colleagues) and their willingness to accept themselves in their present state of development. Now consider these questions: What happens to the individuals mental health on the days, or weeks, or months when successes are limited or non-existent and self-esteem dips into the danger zone? Do they suffer mental setbacks? Not necessarily, since many individuals strive toward goals despite repeated setbacks and dissatisfaction with their current state. An excellent example comes from the life of Abraham Lincoln. According to Branden (1969), a leading exponent of the importance of self-esteem, individuals who experience deep insecurities or self-doubts have nothing to offer the world. Indeed, despite the lack of any empirical evidence, Brandens assumption is typical regarding the benets of high self-esteem. Yet, Dawes (1994) cited Abraham Lincoln as one of the many admirable people who have suffered from deep insecurities and self-doubts. What keeps such a person from falling into the psychopathological trap of lowered self-esteem? Could it be that there is a related concept that ensures that an individuals sense of worth is not dependent on learning to read before everyone else, making a hit in the baseball game, or being awarded a job promotion? Might that concept be selfrespect? We submit that those who respect themselves believe that they are worth the effort it takes to consider their disappointments and failures as closely as their triumphs and successes. They believe that they are worth the effort needed to try again tomorrow and will set new goals, rather than remain satised with their present ability or level of maturity. Viewed in this context, self-respect is the couch on which the cushion of self-esteem resides. Self-respect is more than just the consideration and appreciation of ones own personal attributes, talents or accomplishments. It becomes the core of ones psychological strength by proclaiming worth in the simple fact of ones existence, providing protection from despair in the face of setbacks or failures, and furnishing guidance and purpose for ones future.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

272

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX

The objective components of self-respect provide guidelines and structure. Behaviors that are respectful towards the self and others can be dened and observed. When individuals are struggling with problems or issues, specics are much more valuable in helping them determine a course of action than subjective afrmations of ones worth or potential. Pipher (1997) has found in her years as a therapist that many adults try to bolster their self-esteem with self-afrmation tapes and self-help books. These media are designed to convince the listeners or readers that they are good people and should feel good. Although these messages may have their place, they mask the need for concrete changes in ones goals and behaviors (Dawes, 1994). If ones work is meaningless or ones relationships are fragmented, approaches are needed that are specic in terms of behaviors (e.g., Borkovec & Costello, 1993; Halford et al., 1994; Jacobson, 1992) that can bring about change. Based on the tenets of the sociometer theory, Leary (1999, p. 215) has suggested that some people ought to have low self-esteem. Those who behave in destructive and inappropriate ways that lead to exclusion experience low self-esteem because their sociometer has accurately detected a threat to inclusion. Change is what is needed, not messages of self-afrmation. The attempt to rid oneself of unpleasant feelings through self-afrmation points to another potential difference between self-esteem and self-respect. When the feelings of both shame (feeling of disgrace or dishonor) and guilt (feeling of responsibility for a wrongdoing) are appropriate, they serve useful purposes in preserving self-respect. Feelings of shame are a warning signal that one is struggling with ones conviction to valued standards or has lost condence in ones ability to meet these standards (Taylor, 1995). Self-afrmation without prior self-evaluation ignores the underlying causes of the shame and prevents one from identifying the thought processes or events that preceded the feeling. Without this self-survey and evaluation, individuals cannot take the necessary actions to recommit to their espoused values. Likewise guilt, if appropriate, preserves self-respecting behavior. Guilt is a sensation of anxiety that occurs when one engages in an action that violates ones standards (Taylor, 1995). Anxiety serves as an interrupt mechanism by interrupting the behavioral chain that may culminate in undesired behavior and prompting cognitive reassessment (Baumeister & Tice, 1990). Efforts to avoid this anxiety motivate individuals to refrain from behavior that would undermine their self-respect. Self-respect also provides guidelines for parents who may be struggling with their child-rearing efforts. Helping children to make decisions and expecting behaviors from them that are consistent with respect offers both children and adults concrete direction. Many parents are more concerned about their childrens feelings than their behaviors and as a result focus on cultivating self-esteem, and other goals such as creativity, sociability, or parental love, rather than self-control (Baumeister et al., 1994). As noted earlier, Baumeister et al. (1994) voiced their concern regarding the attention given to self-esteem and the lack of attention afforded self-regulation. They explained that in studying the self, psychologists and social scientists have paid a great deal of attention to self-concept, self-esteem, and self-presentation. Yet,

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

SELF-RESPECT

273

although the issue of self-regulation was considered in the 1960s, most of the self-regulation literature did not appear until the late 1980s. Social interest is offered as one explanation for this delay. Baumeister et al. (1994) suggested that understanding self-concept and the formation of identity were of interest when the baby boomers were in their adolescence and trying to nd themselves. When the baby boom generation began developing careers, attention turned to issues of selfpresentation. Then, during the 1980s, growing and pervasive social problems related to individuals inability to delay gratication and control impulses turned attention to issues of self-control. Self-regulation involves starting, stopping or changing a process. It is initiated by competition among parallel processes (Baumeister et al., 1994), such as the desire to smoke a cigarette and quit smoking. A hierarchy exists among processes such that, when attention is focused on the higher-level process, the lower-level process is overridden (Carver & Scheier, 1981). Baumeister et al. (1994, p. 8) explained that higher-level processes involve larger time spans, more extensive networks of meaningful associations and interpretations, and more distal and abstract goals. If the higher-level processes do not override the lower-level ones, and instead the lowerlevel processes determine the behavior, self-regulation failure occurs. The basic ingredients for self-regulation include standards, monitoring, and the ability to alter ones behavior in order to bring it into line with ones standards. As noted previously, self-regulation or self-control is an integral component of a self-respect system. Teaching young children self-control, rather than encouraging immediate momentary satisfaction, can provide them with effective skills for social interaction and coping with disappointments or difcult circumstances. In a 10-year-longitudinal study, Mischel et al. (1988) found that 15-year-olds who at the age of 4 and 5 were most able to resist immediate temptation and choose delayed gratication demonstrated superior abilities in school performance, social competence, and the ability to deal effectively with frustration and stress. A follow-up study (Shoda et al., 1990) found that the children with the highest capacity for self-control at age 4 and 5 scored the highest on the SAT entrance exams when applying for college. Thus, the behaviors of self-control, self-survey, and tenacity promote independence and lead to the development of the autonomy needed for self-respect to exist. These actions represent a beginning for those who nd functioning difcult and help those who are able to maintain their functioning to continue their growth as human beings. Autonomy provides the means to control ones behavior. It also provides a foundation for the self such that dependence on others is limited. Harters (1990a) study, as well as Learys (1999) theory of inclusion, illustrated the signicant impact that the opinions of signicant others have on self-esteem. Because of our social nature, the opinions of others will always play a role in an individuals self-image. However, over-dependence on others opinions may be destructive. Individuals may be led to beliefs that are not true, such as I deserve to be beaten. They may be led to engage in unacceptable behaviors such as the crimes of street gangs. They may become dependent on people who may not always be available because of other obligations, termination of the relationship, or even death.

Downloaded by [79.112.42.116] at 15:07 13 February 2013

274

C. E. ROLAND & R. M. FOXX