Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chinese Economic Development and The Obstacles To Southeast Asian Energy Security

Caricato da

Harrison RogersTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chinese Economic Development and The Obstacles To Southeast Asian Energy Security

Caricato da

Harrison RogersCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chinese Economic Development and the Obstacles to Southeast Asian Energy Security Chinas energy consumption has grown

rapidly over the past 20 years. Economic growth has largely been responsible for Chinas increasing energy demand. Now the second largest economy in the world, Chinas economy grew at an annual compound rate of 7.92 percent between 1990 and 2010 while primary energy demand grew at an average annual rate of 9.1 percent over the same period. Meeting Chinas rising energy demand has become a significant problem as consumption has outpaced domestic production. Today, China relies on imports to meet about 30 percent of it total energy needs. In response to rising import levels, China has taken a going-abroad approach to energy policy, aggressively securing energy abroad through joint ventures, project-sharing agreements, and long-term contracts. In 2008 alone, overseas production accounted for 60 to 70 percent of profits for the two of the biggest Chinese state run energy companies, CNPC and CNODC. Yet the energy security implications borne out of Chinas growing energy imports have motivated China to pursue alternative forms of energy specifically natural gas. Natural gas serves as a good substitute to other fuels because it not only burns less carbon emissions than coal or oil but diversifies Chinas energy supply. The Chinese government has recognized these benefits and has pursued natural gas development across globally. Over the past decade, natural gas has grown from an infantile to regional industry. While still only accounting for 3.5 percent of Chinas total primary consumption, natural gas production has grown 255 percent from 27.2 bcm to 96.8 bcm since 2000 and is expected to increase to 250 bcm by 2030. However, natural gas production cannot keep pace with Chinas increasing energy demand. In 2007, China became a net importer of natural gas and currently holds a 12.2 bcm production deficit. The Oxford

Rogers 2 Institute of Energy Studies forecasts Chinas production deficit will only worsen as consumption is predicted to increase 15 percent annually until 2030, exacerbating the annual production deficit to 70 bcm. In light of its increasing production deficit, China has reverted back to its going abroad strategy to meet demand. China has looked to integrate itself in the global natural gas market through transnational pipeline agreements and LNG long-term contracts. Over the last ten years, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Myanmar have all signed pipeline agreements with China, adding an accumulated capacity of 150 bcm in the coming decades. But considering these pipelines arent expected to come online until 2012, 2015, and 2020 respectively, China has looked to LNG as a way to further meet growing imports. Since 2003, China has rapidly developed its LNG pipeline and terminal infrastructure, completing its first LNG terminal in 2006. Today, China imports 3.3 million tones of LNG, which accounts for 14.5 percent of Chinas total import volume. Growth in LNG seems eminent. Two more LNG terminals are under construction with 11 more in consideration. This will continue to open China to the global LNG market as China currently imports LNG from Australia (81%), Egypt (5.6%), Nigeria (5.4%), Algeria (3.8%) and Equatorial Guinea (3.6%). Yet Chinas integration into the global LNG market seems illogical when considering Chinas LNG suppliers. China has opted to import energy from across the globe in Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific while seemingly ignoring Southeast Asian exporters. This comes at a surprise considering the Asian-Pacific region holds 7 percent of the worlds total proven natural gas reserves and has an already established LNG market. Indonesia alone is the 10th largest reserve holder while Malaysia is the largest LNG exporter in the world, accounting for 15 percent of world production. Although China has signed long-term LNG contracts with both

Rogers 3 Malaysia and Indonesia, China hasnt centered its natural gas consumption on Southeast Asias LNG market. China has taken a 17 percent stake in Indonesias Tangguh Project, which will direct 2.6 million tones of LNG annually to China. In addition, Chinas CNOOC-Malaysia contract will direct 3 million tones of LNG to Shanghai annually over the next 25 years. China has also signed a pipeline agreement with Myanmar to construct a 12 bcm pipeline from Myanmars deep-water port of Sittwe to Kunming, in Chinas southwestern Yunnan Province. However, these contracts dont compare to the 30 to 40 bcm central Asian pipeline projects currently under construction and numerous LNG imports from African and the Middle East. This begs the question: why has China been so hesitant to develop LNG resources in Southeast Asia? The answer lies in the Southeast Asian LNG market. The regions current pricing system artificially raises import LNG prices. Higher import LNG prices increase the price differential between domestic and import prices in producing countries. These differentials in turn deter gas investment as producing countries have forced both regional IOCs and NOCs to supply growing domestic markets at subsidized prices before meeting international demand. The limited investment from gas companies in the region has resulted in tightened supply as regional demand increases, preventing China from entering the market. This effect threatens Chinese energy security, as China must rely solely on distant LNG exporters and Central Asian natural gas suppliers, highlighting the need for pricing reform as a way to meet regional demand in the coming decades. The Asian Pacific LNG market has naturally tightened over the past few years as Indonesian and Malaysian gas fields are maturing while regional demand is increasing, creating the need for new investment. The ASEAN Energy Group reports that ASEAN economies have grown at a compounded average rate of 6.2 percent between 2005 and 2010 while gas

Rogers 4 consumption has followed suit increasing at an average compounded rate of 4.8 percent over the same period. However, production has stagnated in the face of rising demand. Indonesias proven reserves have fallen from 3 tcm to 2.9 tcm, Malaysias have increased marginally from 2.3 to 2.4, and Myanmars have leveled off at 3 tcm since 1990. These market conditions have created the need for investment in new production. Producing states have relied on IOCs to invest in upstream development as the majority of ASEAN gas fields are located offshore and require large sums of capital in order to develop and connect them to the mainland gas infrastructure. In Indonesia, the NOC Pertamina owns 90 percent of gas production along with six other IOCs Total, ExxonMobil, Vico, ConocoPhillips, BP, and Chevron. However, IOCs refuse to continue investing in ASEAN gas fields because producing states require IOCs sell their gas under subsidized prices in domestic markets to meet growing demand. As demand has increased throughout the region, ASEAN governments want producing companies to meet domestic demand before selling LNG internationally. This requirement poses a problem for profit-seeking companies because domestic prices are substantially lower than import prices. Domestic gas prices in Indonesia, Malaysia, and other ASEAN countries are sold between 3 and 4 dollars MMbtu below imported prices. In 2008, Malaysias domestic gas was priced at 1.90 dollars/MMbtu while its exported gas was sold at 6.48 dollars/MMbtu. These subsidized prices cost Malaysias NOC, Petronas, 4.5 billion dollars, or 9.1 percent of total revenue on an annual basis. So its no wonder why IOCs are hesitant to invest in upstream development. David Ledesma, of the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies believes ExxonMobil has stalled the development of Indonesias Natuna D Alpha for this reason. While Natuna D Alpha field holds 1.3 tcm of natural gas, which would combat excess demand in the region, ExxonMobil has stalled development for three years even though it claims it has proper

Rogers 5 financing and technology. Ledesma notes, the more costly exploration will add support to the need for international prices for gas to ensure continued development in projects. Indonesian and Malaysian production has stagnated due to the lack of upstream investment in the region, preventing ASEAN from meeting its long-term contracts with Japan and Korea. Since 2005, Indonesia and Malyasias production has plateaued at about 69 bcm and 64 bcm respectively. This has caused supply shortages in the region as exporting countries diverted gas from international long-term contracts to domestic consumers demand. Between 2000 and 2006, Indonesias Asian (Japan, China, and Korean) LNG market share declined from 36 to 22 percent, while Malaysias market share declined from 21 to 20 percent. Likewise, the Middle East and Africas market share has risen from 22 to 32 percent and 2 to 5 percent respectively. As increasing Middle Eastern and African supply has sustained Asian demand, lack of investment in ASEAN gas has prevented China from entering the Southeast Asian market. Decreasing market-share throughout the ASEAN region has produced what David Ledesma coins the Energy Policy Dilemma, where ASEAN governments must weigh the benefits of either meeting contractual obligations or growing domestic demand. The key problem is that Pertamina and international companies are seeking international prices for their gas, but if the government insists that new gas is supplied domestically at lower prices, then new gas exploration may not take place and production will not increase. If however, gas is exported to higher paying markets, then domestic industry may not be developed, with a resulting loss in unemployment and tightened supply. writes Ledesma. As Indonesias and Malaysias contracts with Japan and Korea are set to expire in 2012 and 13 respectively, Indonesia and Malaysia must choose a policy that best honors existing

Rogers 6 obligations while meeting domestic demand. However, this dilemma leaves China outside the ASEAN market as Japan and Korea lobby to extend their long-term contracts. Limited market share within the region forces China to rely solely on Central Asian suppliers and long distance exporters to meet demand, which threatens overall energy security. Central Asian gas poses as a security threat because Russia, India, and Pakistan are already competing for supply. In 2010, Russia bought all 90 bcm of Turkmenistani and Uzbekistani gas at substantially higher prices just so it could its meet European long-term contracts even as China kept pushing up the price. Russias willingness to purchase gas above market value only highlights the scarcity of gas in the region. Yet the real threat to Chinese energy security isnt so much the regional, but international LNG pricing system. The international pricing system distorts the net market value of LNG as it indexes LNG off the Asian price of imported Japanese crude oil, called the Japanese Crude Cocktail or JCC. LNG was originally based off JCC to foster competition between the fuels in Japan. Back in the 1970s, oil directly competed with LNG in the residential, commercial and industrial sectors. 90 per cent of natural gas consumption in Japan in 1979 competed with oilbased energy. Today, however, natural gas predominantly competes against coal in power generation while oil is used only in the transportation sector of Japans economy. The uncompetitiveness between fuels distorts LNG prices, as fluctuations in crude prices dont reflect the supply and demand changes in LNG-based industries. This flawed system has artificially pushed LNG prices higher relative to LNGs net market value as crude prices have increased. This is evident in the slopes of the LNG net market value price to crude price ratio. The JCC ratio registers a slope of 17.4 while the slope of Asias net market value registers a slope of 8.8. JCC and NMV 8.6 degree difference proves that not only does a linkage not exist, but JCC

Rogers 7 pushes prices higher than they should under a market-oriented system. This pricing system has devastating consequences for China, as China must import LNG under artificially high prices. This jeopardizes Chinese energy security. Higher import prices will force the government to continue subsidizing natural gas, which will pull money away from investment in other upstream and downstream projects aimed at increasing supply. In addition, sustained higher prices may potentially threaten the viability of such an infantile industry if the purchase of LNG becomes uneconomical. Therefore, regional pricing reform must occur. A transition to a market-oriented system will pull down import prices, which can promote price uniformity among ASEAN countries as high export revenues will no longer be able to keep subsidized prices low. In addition, market-oriented prices can better measure supply and demand, giving IOCs a better sense of profitability in new production development. All of this, in turn, will provide energy securing to region and boost supply through free-market based development. Hopefully, China can recognize this before it looks across the globe for more supply or will continue to indirectly suffer from the effects of ASEANs Energy Policy, which promotes a tightened market. Rocky Mountain Institute

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- In Defense of Earmarks: Can Earmarks Foster A More Productive Congress?Documento48 pagineIn Defense of Earmarks: Can Earmarks Foster A More Productive Congress?Harrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- Obstacles To Southeast Asian Energy DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineObstacles To Southeast Asian Energy DevelopmentHarrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- In Defense of Earmarks: Can Earmarks Foster A More Productive Congress?Documento48 pagineIn Defense of Earmarks: Can Earmarks Foster A More Productive Congress?Harrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- Saudi Oil Price TheoryDocumento9 pagineSaudi Oil Price TheoryHarrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- Russian SympathyDocumento8 pagineRussian SympathyHarrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- ResumeDocumento2 pagineResumeHarrison RogersNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Proses Perencanaan Pembangunan Dengan Pendekatan Partisipatif Di Kecamatan Tembalang Kota SemarangDocumento15 pagineProses Perencanaan Pembangunan Dengan Pendekatan Partisipatif Di Kecamatan Tembalang Kota Semarangindah 119220118Nessuna valutazione finora

- Read The Text Below To Answer Questions Number 1-4!Documento9 pagineRead The Text Below To Answer Questions Number 1-4!WinnieNessuna valutazione finora

- DG SemarangTimeLineDocumento5 pagineDG SemarangTimeLineAbie FarabieNessuna valutazione finora

- Empowerment of Traders and Traditional Market Potential Development in IndonesiaDocumento9 pagineEmpowerment of Traders and Traditional Market Potential Development in IndonesiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Petrosea Company Profile 2020Documento14 paginePetrosea Company Profile 2020kakashi hatakeNessuna valutazione finora

- Kel. Sidodadi 2Documento21 pagineKel. Sidodadi 2Rimuru TempestNessuna valutazione finora

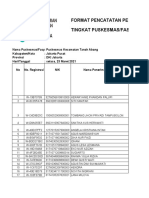

- Format Pencatatan Pelaksanaan Vaksinasi Covid-19 Tingkat Puskesmas/FasyankesDocumento32 pagineFormat Pencatatan Pelaksanaan Vaksinasi Covid-19 Tingkat Puskesmas/FasyankesNeta AuliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Komisi Pemilihan Umum Kabupaten Penajam Paser UtaraDocumento17 pagineKomisi Pemilihan Umum Kabupaten Penajam Paser UtaraOcon WeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sub Sektor Industri Makanan Dan MinumanDocumento4 pagineSub Sektor Industri Makanan Dan MinumanFRASETYO ANGGA SAPUTRA ARNADINessuna valutazione finora

- Ringkasan Saham-20210723Documento90 pagineRingkasan Saham-20210723IrwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Laporan Hasil JuniDocumento56 pagineLaporan Hasil JuniNiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pemerintah Kota Jayapura Dinas Kependudukan Dan Pencatatan SipilDocumento1 paginaPemerintah Kota Jayapura Dinas Kependudukan Dan Pencatatan SipilBobby R SeptiantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Report OSHINDocumento208 pagineReport OSHINResky AinunnisaNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF Burnai Mulya BintangDocumento44 paginePDF Burnai Mulya BintangMedianNessuna valutazione finora

- Indonesian Benchmark Coal Price Rebounds in Jun'18: PricesDocumento24 pagineIndonesian Benchmark Coal Price Rebounds in Jun'18: PricesvivekNessuna valutazione finora

- Kalender Masehi 2023Documento12 pagineKalender Masehi 2023logi techNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Perangkat Desa SendeDocumento5 pagineData Perangkat Desa SendePemdes ArjawinangunNessuna valutazione finora

- A.3-Kpu Adaut#007Documento11 pagineA.3-Kpu Adaut#007Agus SarnulayNessuna valutazione finora

- Bangsalrejo A KWKDocumento96 pagineBangsalrejo A KWKoni0% (1)

- Shipper CiamisDocumento49 pagineShipper CiamisDedin HondaNessuna valutazione finora

- 582 1936 2 PBDocumento20 pagine582 1936 2 PBUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Penerimaan Uang Saku Pns Kegiatan Bantuan Operasional Kesehatan (Dak 2019) Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Indramayu Tahun Anggaran 2019Documento12 pagineDaftar Penerimaan Uang Saku Pns Kegiatan Bantuan Operasional Kesehatan (Dak 2019) Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Indramayu Tahun Anggaran 2019Nesa AgnesNessuna valutazione finora

- Peran Pakubuwono X Dalam Pegembangan Dakwah Islam Di Surakarta 1893-1939Documento13 paginePeran Pakubuwono X Dalam Pegembangan Dakwah Islam Di Surakarta 1893-1939Fahmi SyechansNessuna valutazione finora

- Indonesian Management, Style and CharacteristicDocumento19 pagineIndonesian Management, Style and CharacteristicKarissha FritziNessuna valutazione finora

- JADWAL FT SENIN 05 JUN 23 - ShareOprDocumento280 pagineJADWAL FT SENIN 05 JUN 23 - ShareOprDimas Rido AldinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Country Report IndonesiaDocumento19 pagineCountry Report IndonesiaArya Aya AriyaningsihNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Vitae-Arif MunandarDocumento2 pagineCurriculum Vitae-Arif Munandararif munandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Menu Lavish Iftar Journey 2023 PDFDocumento8 pagineMenu Lavish Iftar Journey 2023 PDFPark SoheeNessuna valutazione finora

- Putri Arum Puspita Sari - 205040100111135 - Assignment 1Documento10 paginePutri Arum Puspita Sari - 205040100111135 - Assignment 1Putri ArumNessuna valutazione finora

- Jadualkuliaha191 PDFDocumento217 pagineJadualkuliaha191 PDFHazman PsNessuna valutazione finora