Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Langmuir Adsorption Model - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Caricato da

Benni WewokCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Langmuir Adsorption Model - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Caricato da

Benni WewokCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Langmuir adsorption model

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

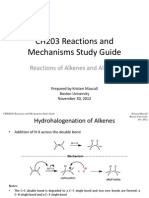

The Langmuir adsorption model is the most common model used to quantify the amount of adsorbate adsorbed on an adsorbent as a function of partial pressure or concentration at a given temperature. It considers adsorption of an ideal gas onto an idealized surface. The gas is presumed to bind at a series of distinct sites on the surface of the solid as indicated in Figure 1, and the adsorption process was treated as a reaction where a gas molecule reacts with an empty site, S, to yield an adsorbed complex

Fig 1. An schematic showing equivalent sites, occupied(blue) and unoccupied(red) clarifying the basic assumptions used in the model. The adsorption sites(heavy dots) are equivalent and can have unit occupancy. Also, the adsorbates are immobile on the surface

Contents

1 Basic assumptions of the model 2 Derivations of the Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm 2.1 Kinetic Derivation 2.2 Statistical Mechanical Derivation 2.3 Competitive Adsorption 2.4 Dissociative Adsorption 3 Entropic considerations 4 Disadvantages of the model 5 Modifications of the Langmuir Adsorption Model 5.1 The Freundlich Adsorption Isotherm 5.2 The Temkin Adsorption Isotherm 5.3 BET equation 6 Adsorption of binary liquid adsorption on solids 7 References

Basic assumptions of the model

Inherent within this model, the following assumptions [1] are valid specifically for the simplest case: the adsorption of a single adsorbate onto a series of equivalent sites on the surface of the solid. 1. The surface containing the adsorbing sites is perfectly flat plane with no corrugations (assume the surface is homogeneous) . 2. The adsorbing gas adsorbs into an immobile state. 3. All sites are equivalent. 4. Each site can hold at most one molecule of A (mono-layer coverage only). 5. There are no interactions between adsorbate molecules on adjacent sites.

Derivations of the Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm

Kinetic Derivation

Main article: Langmuir equation This section [2] provides a kinetic derivation for a single adsorbate case. The multiple adsorbate case is covered in the Competitive adsorption sub-section. The model assumes adsorption and desorption as being elementary processes, where the rate of adsorption rad and the rate of desorption rd are given by:

where PA is the partial pressure of A over the surface, [S] is the concentration of bare sites in number/m, [Aad ] is the surface concentration of A in molecules/m, and k ad and k d are constants. At equilibrium, the rate of adsorption equals the rate of desorption. Setting rad =rd and rearranging, we obtain:

The concentration of all sites [S0 ] is the sum of the concentration of free sites [S] and of occupied sites:

Combining this with the equilibrium equation, we get:

We define now the fraction of the surface sites covered with A, A , as:

This, applied to the previous equation that combined site balance and equilibrium, yields the Langmuir

adsorption isotherm:

Statistical Mechanical Derivation

[3]

This derivation [4] was originally provided by Volmer and Mahnert[5] in 1925. The partition function of the finite number of adsorbents adsorbed on a surface, in a canonical ensemble is given by

where is the partition function of a single adsorbed molecule, are the number of sites available for adsorption. Hence, N, which is the number of molecules that can be adsorbed, can be less or equal to Ns . The first term of Z(n) accounts the total partition function of the different molecules by taking a product of the individual partition functions (Refer to Partition function of subsystems). The latter term accounts for the overcounting arising due to the indistinguishable nature of the adsorption sites. The grand canonical partition function is given by

As it has the form of binomial series, the summation is reduced to

where The Landau free energy, which is generalized Helmholtz free energy is given by

According to the Maxwell relations regarding the change of the Helmholtz free energy with respect to the chemical potential,

which gives

Now, invoking the condition that the system is in equilibrium, the chemical potential of the adsorbates is equal to that of the gas surroundings the absorbent.

An example plot of the surface coverage A = P/(P+P0) with respect to the partial pressure of the adsorbate. P0 = 100mtorr. The graph shows levelling off of the surface coverage at pressures higher than P0.

where N3D is the number of gas molecules, Z3D is the partition function of the gas molecules and Ag =-kBT ln Zg . Further, we get

where

Finally, we have

It is plotted in the figure alongside demonstrating the surface coverage increases quite rapidly with the partial pressure of the adsorbants but levels off after P reaches P0.

Competitive Adsorption

The previous derivations assumes that there is only one species, A, adsorbing onto the surface. This section [6]

considers the case when there are two distinct adsorbates present in the system.Consider two species A and B that compete for the same adsorption sites. The following assumptions are applied here: 1. All the sites are equivalent. 2. Each site can hold at most one molecule of A or one molecule of B, but not both. 3. There are no interactions between adsorbate molecules on adjacent sites. As derived using kinetical considerations, the equilibrium constants for both A and B are given by

and

The site balance states that the concentration of total sites [S0 ] is equal to the sum of free sites, sites occupied by A and sites occupied by B:

Inserting the equilibrium equations and rearranging in the same way we did for the single-species adsorption, we get similar expressions for both A and B:

Dissociative Adsorption

The other case of special importance is when a molecule D2 dissociates into two atoms upon adsorption.[7] Here, the following assumptions would be held to be valid: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. D2 completely dissociates to two molecules of D upon adsorption. The D atoms adsorb onto distinct sites on the surface of the solid and then move around and equilibrate. All sites are equivalent. Each site can hold at most one atom of D. There are no interactions between adsorbate molecules on adjacent sites.

Using similar kinetic considerations, we get:

The 1/2 exponent on pD2 arises because one gas phase molecule produces two adsorbed species. Applying the

site balance as done above:

Entropic considerations

The formation of Langmuir monolayers by adsorption onto a surface dramatically reduces the entropy of the molecular system. This conflicts with the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy will increase in an isolated system. This implies that either another locally active force is stronger than the thermodynamic potential, or that our expression of the entropy of the system is incomplete. To find the entropy decrease, we find the entropy of the molecule when in the adsorbed condition.[8]

Using Stirling's approximation, we have,

On the other hand, the entropy of a molecule of an ideal gas is

where

is the Thermal de Broglie wavelength of the gas molecule.

Disadvantages of the model

The Langmuir adsorption model deviates significantly in many cases, primarily because it fails to account for the surface roughness of the adsorbate. Rough inhomogeneous surfaces have multiple site-types available for adsorption, and some parameters vary from site to site, such as the heat of adsorption. The model also ignores adsorbate/adsorbate interactions. Experimentally, there is clear evidence for adsorbate/adsorbate interactions in heat of adsorption data. There are two kinds of adsorbate/adsorbate interactions: direct interaction and indirect interaction. Direct interactions are between adjacent adsorbed molecules, which could make adsorbing near another adsorbate molecule more or less favorable and greatly affects high-coverage behavior. In indirect interactions, the adsorbate changes the surface around the adsorbed site, which in turn affects the adsorption of other adsorbate molecules nearby.

Modifications of the Langmuir Adsorption Model

The modifications try to account for the points mentioned in above section like surface roughness, inhomogeneity, and adsorbate-adsorbate interactions.

The Freundlich Adsorption Isotherm

The Freundlich isotherm is the most important multisite adsorption isotherm for rough surfaces.

where F and CF are fitting parameters.[9] This equation implies that if one makes a log-log plot of adsorption data, the data will fit a straight line. The Freundlich isotherm has two parameters while Langmuir's equations has only one: as a result, it often fits the data on rough surfaces better than the Langmuir's equations. A related equation is the Toth equation. Rearranging the Langmuir equation, one can obtain:

Toth[10] modified this equation by adding two parameters, T0 and CT0 to formulate the Toth equation:

The Temkin Adsorption Isotherm

This isotherm takes into accounts of indirect adsorbate-adsorbate interactions on adsorption isotherms. Temkin[11] noted experimentally that heats of adsorption would more often decrease than increase with increasing coverage. The heat of adsorption Had is defined as:

He derived a model assuming that as the surface is loaded up with adsorbate, the heat of adsorption of all the molecules in the layer would decrease linearly with coverage due to adsorbate/adsorbate interactions:

where T is a fitting parameter. Assuming the Langmuir Adsorption isotherm still applied to the adsorbed layer, is expected to vary with coverage, as follows:

Langmuir's isotherm can be rearranged to this form:

Substituting the expression of the equilibrium constant and taking the natural logarithm:

BET equation

Main article: BET theory Brunauer, Emmett and Teller[12] derived the first isotherm for multilayer adsorption. It assumes a random distribution of sites that are empty or that are covered with by one monolayer, two layers and so on, as illustrated alongside. The main equation of this model is:

Brunauer's model of multilayer adsorption, that is, a random distribution of sites covered by one, two, three, etc., adsorbate molecules.

where

and [A] is the total concentration of molecules on the surface, given by:

where

in which [A] 0 is the number of bare sites, and [A] i is the number of surface sites covered by i molecules.

Adsorption of binary liquid adsorption on solids

Main article: Surface excess isotherm This section describes the surface coverage when the adsorbate is in liquid phase and is a binary mixture[13] For ideal both phases - no lateral interactions, homogeneous surface - the composition of a surface phase for a

binary liquid system in contact with solid surface is given by a classic Everett isotherm equation (being a simple analogue of Langmuir equation), where the components are interchangeable (i.e. "1" may be exchanged to "2") without change of eq. form:

where the normal definition of multicomponent system is valid as follows :

By simple rearrangement, we get

This equation describes competition of components "1" and "2".

References

1. ^ Principles of Adsorption and Reaction on Solid Surfaces. Wiley Interscience. 1996. pp. 240. ISBN 0-47130392-5. 2. ^ Principles of Adsorption and Reaction on Solid Surfaces. Wiley Interscience. 1996. pp. 240. ISBN 0-47130392-5. 3. ^ Cahill, David (2008). "Lecture Notes 5 Page 2" (http://www.library.uiuc.edu/ereserves/item.asp?id=35598) (pdf). University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign. http://www.library.uiuc.edu/ereserves/item.asp?id=35598. Retrieved 2008-11-09. 4. ^ Principles of Adsorption and Reaction on Solid Surfaces. Wiley Interscience. 1996. pp. 242. ISBN 0-47130392-5. 5. ^ Volmer, M.A., and P. Mahnert, Z. Physik. Chem 115, 253 6. ^ Principles of Adsorption and Reaction on Solid Surfaces. Wiley Interscience. 1996. pp. 244. ISBN 0-47130392-5. 7. ^ Principles of Adsorption and Reaction on Solid Surfaces. Wiley Interscience. 1996. pp. 244. ISBN 0-47130392-5. 8. ^ Cahill, David (2008). "Lecture Notes 5 Page 13" (http://www.library.uiuc.edu/ereserves/item.asp?id=35598) (pdf). University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign. http://www.library.uiuc.edu/ereserves/item.asp?id=35598. Retrieved 2008-11-09. 9. ^ Freundlich, H. Kapillarchemie, Academishe Bibliotek, Leipzig (1909) 10. ^ Toth, J., Acta. Chim. Acad. Sci. Hung 69, 311(1971) 11. ^ Temkin, M.I., and V. Pyzhev, Acta Physiochim. URSS 12,217(1940) 12. ^ J. Am. Chem. Soc 60,309 13. ^ Marczewski, A. W (2002). "Basics of Liquid Adsorption" (http://www.adsorption.org/awm/ads/Basics.htm#Liquid) . http://www.adsorption.org/awm/ads/Basics.htm#Liquid. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Langmuir_adsorption_model&oldid=526590496" Categories: Surface chemistry Materials science This page was last modified on 5 December 2012 at 20:35. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may

apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 8th International Congress On Science and Technology of Ironmaking - ICSTI 2018 - Book of AbstractsDocumento101 pagine8th International Congress On Science and Technology of Ironmaking - ICSTI 2018 - Book of AbstractsEly Wagner FerreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Composite Pressure VesselsDocumento22 pagineComposite Pressure VesselsInternational Journal of Research in Engineering and TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat - Mass Balance at ULCOS PDFDocumento3 pagineHeat - Mass Balance at ULCOS PDFROWHEITNessuna valutazione finora

- Decomposition Reaction of LimestoneDocumento4 pagineDecomposition Reaction of LimestoneNovie ArysantiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Dual Graphic Representation of The Blast Furnace Mass and Heat BalancesDocumento11 pagineA Dual Graphic Representation of The Blast Furnace Mass and Heat Balancesfarage100% (1)

- Saint Louis University School of Engineering and Architecture Department of Chemical EngineeringDocumento132 pagineSaint Louis University School of Engineering and Architecture Department of Chemical EngineeringPaul Philip LabitoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes Study GuideDocumento17 pagineReactions of Alkenes and Alkynes Study GuideMelissa GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambridge IGCSE Combined and Co Ordinated Sciences Tom Duncan, BryanDocumento545 pagineCambridge IGCSE Combined and Co Ordinated Sciences Tom Duncan, Bryanlynx x100% (3)

- ASTM D2281-10 Standard Test Method For Evaluation of Wetting Agents by Skein TestDocumento3 pagineASTM D2281-10 Standard Test Method For Evaluation of Wetting Agents by Skein TestDerek Vaughn100% (1)

- Innovative DR Technology For Innovative SteelmakingDocumento23 pagineInnovative DR Technology For Innovative SteelmakingrxpeNessuna valutazione finora

- Coal ChemicalDocumento71 pagineCoal ChemicalKiran KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Modeling and Simulations of A Reformer U PDFDocumento8 pagineModeling and Simulations of A Reformer U PDFali AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- MetallurgyDocumento39 pagineMetallurgyPrabhakar BandaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Waste Water - Coke PlantDocumento13 pagineWaste Water - Coke PlantSejla Becirovic Cehajic100% (1)

- Lecture34 - Material and Heat Balance in ConvertingDocumento5 pagineLecture34 - Material and Heat Balance in ConvertingRoger RumbuNessuna valutazione finora

- Uses and Applications of AmmoniaDocumento5 pagineUses and Applications of AmmoniaSohail Asghar100% (2)

- Coke Oven Gas Purification and Cooling ProcessDocumento3 pagineCoke Oven Gas Purification and Cooling Processshishir18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Municipal Solid Waste Project SKTGDocumento3 pagineMunicipal Solid Waste Project SKTGDevanSandrasakerenNessuna valutazione finora

- Topology OptimizationDocumento11 pagineTopology OptimizationSagar Gawde100% (1)

- Temperature Sensors CAT1667Documento36 pagineTemperature Sensors CAT1667damienwckNessuna valutazione finora

- Nioec SP 00 10Documento7 pagineNioec SP 00 10Amirhossein DavoodiNessuna valutazione finora

- BF SlagDocumento9 pagineBF SlagSuresh BabuNessuna valutazione finora

- Production of IronDocumento15 pagineProduction of IronMassy KappsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tecnored Process - High Potential in Using Different Kinds of Solid FuelsDocumento5 pagineTecnored Process - High Potential in Using Different Kinds of Solid FuelsRogerio CannoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting Silicomanganese Production Using Manganese Rich Slag in The ChargeDocumento3 pagineFactors Affecting Silicomanganese Production Using Manganese Rich Slag in The ChargePushkar KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Main Combustion ChamberDocumento31 pagineMain Combustion Chambershaliq28Nessuna valutazione finora

- As 4264.5-1999 Coal and Coke - Sampling Guide To The Inspection of Mechanical Sampling SystemsDocumento6 pagineAs 4264.5-1999 Coal and Coke - Sampling Guide To The Inspection of Mechanical Sampling SystemsSAI Global - APACNessuna valutazione finora

- Tds Fire Clay Brick Sk30 enDocumento1 paginaTds Fire Clay Brick Sk30 enjcljeNessuna valutazione finora

- Fluxes For Electroslag Refining: Dr. Satadal GhoraiDocumento21 pagineFluxes For Electroslag Refining: Dr. Satadal GhoraiGarry's GamingNessuna valutazione finora

- Kinetics of Fluidized Bed Iron Ore ReductionDocumento8 pagineKinetics of Fluidized Bed Iron Ore ReductionMaulana RakhmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Arya General Cata 2016Documento12 pagineArya General Cata 2016Gloria HamiltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Mechanical Topics - Skive ProjectsDocumento15 pagineMechanical Topics - Skive ProjectsJithin V KNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 - Energy Utilisation, Conversion, ConservationDocumento92 pagine09 - Energy Utilisation, Conversion, ConservationAndrew Bull100% (1)

- Free Physical Chemistry Books PDFDocumento2 pagineFree Physical Chemistry Books PDFJessieNessuna valutazione finora

- Tender Current TransformerDocumento6 pagineTender Current TransformerBrijesh SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Design, Manufacturing and Testing of Induction Furnace: Submitted byDocumento65 pagineDesign, Manufacturing and Testing of Induction Furnace: Submitted byGuru ChaudhariNessuna valutazione finora

- BFG Safety How To PreventDocumento25 pagineBFG Safety How To PreventPower PowerNessuna valutazione finora

- Electric Arc Furnace Injection System For OxygenDocumento7 pagineElectric Arc Furnace Injection System For OxygenIcilma LiraNessuna valutazione finora

- BF Dry GCP S-13 PDFDocumento2 pagineBF Dry GCP S-13 PDFgautamcool100% (1)

- Asme B16.47 - 2011Documento120 pagineAsme B16.47 - 2011Guido KünstlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes - Thermal Vs Non-Thermal PlasmaDocumento2 pagineNotes - Thermal Vs Non-Thermal Plasmaanmol3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ecomak - 2019 DeSOx PresentationDocumento37 pagineEcomak - 2019 DeSOx PresentationHsein WangNessuna valutazione finora

- HydrogenDocumento10 pagineHydrogentony jammerNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnesium HydrideDocumento16 pagineMagnesium Hydridefraniq2007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Colla 2016Documento19 pagineColla 2016Venkatakrishnan P.G.Nessuna valutazione finora

- THE EFFECT OF FOAMY SLAG IN THE ELECTRIC ARC FURNACES ON ELECTRIC Energy Consumption PDFDocumento10 pagineTHE EFFECT OF FOAMY SLAG IN THE ELECTRIC ARC FURNACES ON ELECTRIC Energy Consumption PDFManojlovic VasoNessuna valutazione finora

- Alumina Brick RESCODocumento2 pagineAlumina Brick RESCOgems_gce074325Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aist 2018 ZR and Hyl Iii PDFDocumento28 pagineAist 2018 ZR and Hyl Iii PDFteresaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 4 MetallurgyDocumento33 pagineUnit 4 MetallurgyKamlesh PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- 10208-15101387124325secondary Steel Making OverviewDocumento13 pagine10208-15101387124325secondary Steel Making OverviewOmar TahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 4 v3 PDFDocumento12 pagineUnit 4 v3 PDFCh RajuNessuna valutazione finora

- CorrosionDocumento144 pagineCorrosionYassin AmrirNessuna valutazione finora

- Byproduct Operations and ProcessDocumento8 pagineByproduct Operations and ProcessAbhaySnghNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy and Exergy of Electric Arc Furnace PDFDocumento26 pagineEnergy and Exergy of Electric Arc Furnace PDFChristopher LloydNessuna valutazione finora

- CO&CCPDocumento23 pagineCO&CCPApoorva RamagiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Msds PitchDocumento8 pagineMsds PitchasnandyNessuna valutazione finora

- Vaibhav Furnaces: Some Snap ShotsDocumento6 pagineVaibhav Furnaces: Some Snap ShotsVaibhav FurnacesNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 2 Basic Combustion Chemistry PDFDocumento77 pagineChap 2 Basic Combustion Chemistry PDFMelvin MhdsNessuna valutazione finora

- Converting Mass Flow RateDocumento3 pagineConverting Mass Flow RateAgung PriambodhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Utilization of Fly Ash and Rice Husk Ash As A Supplement To Concrete Materials - A Critical ReviewDocumento9 pagineUtilization of Fly Ash and Rice Husk Ash As A Supplement To Concrete Materials - A Critical Reviewijetrm journalNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Models of Simultaneous Heat and Mass TransferDocumento9 pagineBasic Models of Simultaneous Heat and Mass TransferSaurabh KinareNessuna valutazione finora

- Chlorine: International Thermodynamic Tables of the Fluid StateDa EverandChlorine: International Thermodynamic Tables of the Fluid StateNessuna valutazione finora

- The Langmuir IsothermDocumento12 pagineThe Langmuir IsothermAlejandro MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- Physical Chemistry LaboratoryDocumento8 paginePhysical Chemistry Laboratorydaimon_pNessuna valutazione finora

- Ionic ConductorsDocumento20 pagineIonic ConductorsGregorio GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- IR Absorption TableDocumento2 pagineIR Absorption TablefikrifazNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Interpretation of Infrared SpectraDocumento3 pagineIntroduction To Interpretation of Infrared SpectraBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Solomons Organic Chemistry Module IR TableDocumento1 paginaSolomons Organic Chemistry Module IR TableBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Polymer BiodegradationDocumento12 paginePolymer BiodegradationBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is CivilizationDocumento1 paginaWhat Is CivilizationBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Pyrolysis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento9 paginePyrolysis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Lorentz-Lorenz Equation - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento1 paginaLorentz-Lorenz Equation - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Examples of Stokes' Theorem and Gauss' Divergence TheoremDocumento6 pagineExamples of Stokes' Theorem and Gauss' Divergence TheoremBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- RejangDocumento1 paginaRejangBenni WewokNessuna valutazione finora

- Ic-0014 Kit Refrifluid B Uc-0020-1700 (En)Documento2 pagineIc-0014 Kit Refrifluid B Uc-0020-1700 (En)Lluis Cuevas EstradaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 - Cementing Additives CL Jun-00-ADocumento37 pagine4 - Cementing Additives CL Jun-00-Anwosu_dixonNessuna valutazione finora

- Wastewater - Types, Characteristics & RegulationDocumento50 pagineWastewater - Types, Characteristics & Regulationsam samNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry and Electricity:: ElectrochemistryDocumento5 pagineChemistry and Electricity:: ElectrochemistrySuleman TariqNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalog AU480 1Documento2 pagineCatalog AU480 1Trần Anh TuấnNessuna valutazione finora

- Ib Chemistry: Higher LevelDocumento72 pagineIb Chemistry: Higher LeveldeveenNessuna valutazione finora

- IB Biology - Respiration SL Quiz 2.8Documento5 pagineIB Biology - Respiration SL Quiz 2.8Ameen amediNessuna valutazione finora

- Physical Geography of The Sea and Its MeteorologyDocumento538 paginePhysical Geography of The Sea and Its MeteorologyRachel O'Reilly0% (1)

- Reaction Engineering EP 319/EP 327: Chapter 4 (Part Ii) Multiple ReactionsDocumento25 pagineReaction Engineering EP 319/EP 327: Chapter 4 (Part Ii) Multiple ReactionsWoMeiYouNessuna valutazione finora

- Classroom Contact Programme: Pre-Medical: Nurture Course Phase - MNBJ & MnpsDocumento28 pagineClassroom Contact Programme: Pre-Medical: Nurture Course Phase - MNBJ & MnpsPrakhar KataraNessuna valutazione finora

- Kimre Aiche 2008Documento12 pagineKimre Aiche 2008Marcelo PerettiNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Sun-Baked Stabilized Soil Blocks For BuildingsDocumento115 pagine3 Sun-Baked Stabilized Soil Blocks For BuildingsYousif MawloodNessuna valutazione finora

- Tabalbag Leonor ScienceDocumento9 pagineTabalbag Leonor Scienceemo mHAYNessuna valutazione finora

- Flux Decline in Skim Milk UltrafiltrationDocumento19 pagineFlux Decline in Skim Milk Ultrafiltrationpremnath.sNessuna valutazione finora

- Similitude, Dimensional Analysis ModelingDocumento128 pagineSimilitude, Dimensional Analysis ModelingMostafa Ayman Mohammed NageebNessuna valutazione finora

- City College of San Jose Del MonteDocumento13 pagineCity College of San Jose Del MonteLopez Marc JaysonNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2: Vapor PressureDocumento3 pagineAssignment 2: Vapor PressureRanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bonding, Structure and Periodicity TestDocumento8 pagineBonding, Structure and Periodicity Testpaulcampbell37Nessuna valutazione finora

- Haloalkanes and Haloarenes Worksheet 16 With SolutionsDocumento13 pagineHaloalkanes and Haloarenes Worksheet 16 With Solutionsvircritharun718Nessuna valutazione finora

- TE - Mech - RAC - Chapter 3 - RefrigerantsDocumento57 pagineTE - Mech - RAC - Chapter 3 - RefrigerantsAniket MandalNessuna valutazione finora

- Millipore Express SHC Hydrophilic Filters: High Capacity, Sterilizing-Grade PES FiltersDocumento12 pagineMillipore Express SHC Hydrophilic Filters: High Capacity, Sterilizing-Grade PES FiltersVinoth KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Studies On Bound Water in PvaDocumento4 pagineStudies On Bound Water in PvasggdgdNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.8 and 2.9 Gravity + Analysing Forces in EquilibriumDocumento9 pagine2.8 and 2.9 Gravity + Analysing Forces in EquilibriumRajeswary ThirupathyNessuna valutazione finora

- Iso 20819 2018Documento9 pagineIso 20819 2018Rafid AriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Borates PresentationDocumento20 pagineBorates Presentationpoly6icsNessuna valutazione finora

- Especificaciones Ups YorksDocumento4 pagineEspecificaciones Ups Yorksluisgerardogonzalez8Nessuna valutazione finora