Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Congenital Esophageal Anomalies

Caricato da

blast2111Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Congenital Esophageal Anomalies

Caricato da

blast2111Copyright:

Formati disponibili

TRACHEO-ESOPHAGEAL FISTULA/ ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA INTRODUCTION Congenital Esophageal atresia (EA) and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) are common

congenital anomalies, affecting 1 in 2,400 to 4,500 individuals. Respiratory sequelae are common and may persist life-long. While EA and TEF may exist as separate congenital anomalies, the great majority of patients with these congenital malformations have both EA and TEF. Most patients with TEFs are diagnosed immediately following birth or during infancy. TEFs are often associated with life-threatening complications, so they are usually diagnosed in the neonatal period. In rare cases, patients with a congenital TEF may present in adulthood. HISTORY OF TEF EA was first reported by William Durston in 1670, and in 1697 Thomas Gibson described EA with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). The management of such malformations proved to be challenging, with the first unsuccessful attempt at TEF ligation in 1913 by Harry Richter who performed a transpleural ligation of the fistula and a gastrostomy to provide nutrition. From 1936 to 1938 Thomas Lanman and Robert Shaw independently attempted extrapleural ligations of TEF with primary anastomoses in five separate cases, all resulting in eventual death in the immediate postoperative period. The first survivors were reported independently by N. Logan Leven and William Ladd in 1939 using a multistaged approach that included placement of a gastrostomy tube, extrapleural division of TEF, and cervical esophagostomy. Gastrointestinal continuity was established using an antethoracic skin tube from the gastrostomy to esophagostomy. Although continuity was established, the repaired esophagus did not have normal peristalsis. In 1941 Cameron Haight performed the first successful primary repair of EA with TEF after initial resuscitation of his 12-day-old patient by ligating the TEF using a left extrapleural approach followed by end-toend single layer anastomosis with interrupted silk sutures . The operative treatment today still uses concepts used by these pioneering surgeons, with the biggest advancements being made in the supportive management of the postoperative neonate. The rates of survival have significantly improved from approximately 50% in the 1940s to greater than 90% today . DEFINITION Esophageal atresia is defined as a complete interruption in the continuity of the esophageal lumen. TEF may be defined as a congenital, fistulous connection between the proximal and/or distal esophagus, and the airway. EPIDEMIOLOGY The incidence of EA with or without TEF is approximately 2 in 10,000 births with a slight male predominance. Whites tend to be affected more often than non-whites. Increased incidence is seen in first pregnancies and advanced maternal age; the rate of chromosomal abnormalities and rate of twin pregnancy is increased from rates in the general population .

The most common anomaly is EA with distal TEF (Type C, 85%90%), followed by EA alone (Type A, 7% 8%), TEF without EA (Type E, 4%5%), EA with proximal TEF (Type B, 1%), and EA with fistula to both pouches (Type E, 1%) . Associated congenital malformations are seen in approximately 50% of the cases; other gastrointestinal malformations are seen in 25% of the cases, and VACTERL association (vertebral/vascular, anorectal, cardiac, tracheoesophageal, radial/renal, limb deformities) occur in 20% of patients who have EA. ETIOLOGY Congenital Genetic. Idiopathic. Chromosomal anomalies or as a part of various syndrome. o An association with trisomies 18, 21, and 13 has been reported. Maternal teratogenic drug use ante-natally.

Acquired Secondary to malignant disease, infection, ruptured diverticula, and trauma. Postintubation TEFs- uncommon- following prolonged mechanical ventilation with an ET or TT.

EMBRYOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS OF CONGENITAL TEF The esophagus and trachea both develop from the primitive foregut. During fetal development, the foregut is formed around the 20th day of gestation . On day 22, the pharyngeal groove appears in the ventral aspect of the primitive foregut and within the next few days the lung bud forms at this locus. The mesenchyme between the foregut and the developing bronchial tree gives rise to the tracheoesophageal septum. The longitudinal tracheoesophageal fold fuses to form a septum that divides the foregut into a ventral laryngotracheal tube and a dorsal esophagus. The posterior deviation of the tracheoesophageal septum causes incomplete separation of the esophagus from the laryngotracheal tube and results in a TEF. According to the classic theory, aberrant formation of the tracheoesophageal septum results from abnormal fusion of the lateral folds and may result in anomalous connections between the respiratory and digestive tracts. While studying chick embryos, however, Kluth and Fiegel found no evidence of lateral folds during embryogenesis, but depicted a series of cranial and caudal folds in the region of tracheoesophageal separation. According to the chick embryo model, failure of appropriate development of these folds results in EA or tracheoesophageal fistula. Other investigators further demonstrated the role of epithelial proliferation and apoptosis in the development of the tracheoesophageal septum using the Adriamycin rat model

[The median pharyngeal groove develops in the ventral aspect of foregut at day 22 of gestation. This

tissue develops into the respiratory and digestive tubes. Normally, mesenchyme proliferating between the respiratory and digestive tubes separates the tubes. While several theories have attempted to explain the etiology of EA/TEF, it is currently believed that the development of an abnormal epithelial-lined connection between the two tubes results in the creation of a TEF. The excess tissue growth may lead to incorporation of part of the esophagus into the posterior wall of the trachea. Excess mesenchymal growth can stretch and disrupt the esophagus, creating EA

Thomas Kovesi, Steven Rubin: CHEST 2004]

The presence of EA/TEF also disrupts the normal in utero development of the myenteric plexus in the esophagus, leading to disordered peristalsis and impaired lower esophageal sphincter function. Loss of the ciliated epithelial lining of the trachea may also be present, and squamous epithelium, lacking both ciliated and goblet cells, appears to be particularly prevalent in the posterior muscular portion of the trachea around the area of the original fistula site, although it may be widespread. However, it is unclear whether this represents a developmental anomaly, or is secondary to aspiration. The trachea, particularly at the site of the previous EA/TEF, typically retains a U-shaped configuration, with a wide membranous portion, rather than the normal C-shape, with a short membranous portion. This commonly leads to tracheomalacia of varying degrees of severity.

CLASSIFICATION Initial classification system for EA was developed by E.C. Vogt in 1929. This system was slightly modified and the numerical nomenclature was transformed into an alphabetic one by Gross. This classification system groups the anomalies into: EA without TEF (type A), EA with proximal TEF (type B), EA with distal TEF (type C), EA with TEF between both esophageal segments and trachea (type D), TEF without EA or H-type fistula (type E), and esophageal stenosis (type F).

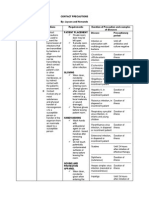

Another classification system developed by Waterston and colleagues in 1962 focused on risk factors and predicted survival in infants who have EA. In the 1990s, Spitz and colleagues included birth weight and presence of cardiac anomalies and proposed a system that is currently used as an alternative to the Waterston classification. Waterston classification of esophageal atresia based on birth weight, presence of risk factors, and predicted survival Group Birth weight A >2500 g B 20002500 g >2500 g C <2000 g >2000 g General health Otherwise healthy Otherwise healthy Moderate associated anomalies (noncardiac, PDA, VSD, ASD) Otherwise healthy Severe associated cardiac anomalies Survival 100% 85% 65%

Spitz classification of esophageal atresia based on birth weight, presence of cardiac defects, and predicted survival Group I II III Characteristics Birth wt >1500 g, no major cardiac defects Birth wt <1500 g or major cardiac defects Birth wt <1500 g, major cardiac defects Survival rate 97% 59% 22%

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Symptoms suspicious for EA/TEF can be observed shortly after birth and may include: Excessive salivation/ Drooling Regurgitation, coughing, and choking following initial attempts to feed the neonate Respiratory distress Cyanosis Inability to advance a catheter into the stomach. The nasogastric tube may curl in the proximal pouch suggesting atresia A distended, air-filled abdomen is suggestive of EA with a distal TEF (Type C) because of the passage of air from the trachea into the gastrointestinal tract. Scaphoid abdomen = EA Distented abdomen = TEF Recurrent Pneumonia , atelectasis

DIAGNOSIS 1. Prenatal diagnosis Presence of polyhydramnios- results from the inability of amniotic fluid to reach the stomach in pure EA and decreased amniotic fluid ingestion in cases of TEF with or without EA. Prominent esophageal pouch

2. 3.

4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

Small or absent stomach bubble with fluid-filled loops of bowel on ultrasonography, usually in the third trimester of pregnancy. Prenatal MRI- blind esophageal pouch. Clinical features- excessive salivation; regurgitation, coughing, and choking following initial attempts to feed the neonate; respiratory distress; cyanosis, recurrent pneumonia. chest and abdominal radiograph- an air-filled blind pouch with EA, presence of air in the gastrointestinal tract in cases of distal TEF, and pneumonia because of the presence of gastric reflux into the lung from a distal TEF. The presence of a proximal air-filled pouch and a gasless abdomen is suggestive of EA without TEF (Type A). Diagnosis of H-type fistula (type E) is usually made using nonionic water-soluble contrast or diluted barium during a radiographic study Oro/nasogastric tube insertion- inability to pass in EA. Flexible bronchoscopy / esophagoscopy CT, virtual bronchoscopy, and MRI -their role in the diagnosis is not yet clear. The presence of components of the VACTERL association should increase suspicion for EA. Approximately 50% of patients who have EA or TEF present with additional birth defects. Complete evaluation should include: plain radiographs of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and spine; ultrasound exams of the spine and kidneys; and echocardiography of the heart and aorta.

ASSOCIATED CONGENITAL ANOMALIES EA/TEF is commonly associated with other congenital anomalies overall, approximately 25% of patients have other congenital defects. Other defects are present most commonly in patients with isolated EA, where other anomalies are present in 50 to 70% of patients. The most common congenital anomalies associated with EA/TEF patients are cardiac (35% of patients), genitourinary (24% of patients), GI (24% of patients), skeletal (13% of patients), and CNS anomalies (10% of patients). VACTERL association is also seen. Tracheal bronchus and absence of the bronchus to the right upper lobe were frequent in neonates with EA/TEF screened by bronchoscopy. A variety of congenital lung anomalies, including pulmonary and lobar agenesis, horseshoe lung, and pulmonary hypoplasia, have also be reported in individuals with EA/TEF. This suggests that all these conditions may be part of what has been termed a general foregut malformation. EA/TEF has also been reported in patients with the DiGeorge syndrome, Down syndrome, and Pierre- Robin sequence. A second association of coloboma, heart anomalies, atresia choanae, retardation, and genital and ear anomalies is known as the CHARGE association, and has also been associated with EA/TEF. REFERENCE 1. Olga Achildi, Harsh Grewal. Congenital Anomalies of the Esophagus. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2006.10.010 2. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/186735-overview 3. Gudovsky L M, Koroleva N S, Biryukov Y B, Chernousov A F, Perelman M I. Tracheoesophageal Fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;55:868-875. 4. Kovesi T, Rubin S. Long-term Complications of Congenital Esophageal Atresia and/or Tracheoesophageal Fistula. Chest 2004;126;915-925. 5. Wong D L, Hockenberry M J. nursing care of infants and children. Mosby: 7th ed.; St.Louis. 2003.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Congenital AnomaliesDocumento22 pagineCongenital Anomaliesjessy100% (1)

- Nursing Care of Children With Indian Childhood Cirrhosis, Wilsons Disesase, Reyes SyndromeDocumento26 pagineNursing Care of Children With Indian Childhood Cirrhosis, Wilsons Disesase, Reyes SyndromeDivya Nair100% (2)

- NEONATAL APNOEA SMNRDocumento18 pagineNEONATAL APNOEA SMNRAswathy RC100% (1)

- Exclusivebreastfeeding 181003124754Documento39 pagineExclusivebreastfeeding 181003124754apalanavedNessuna valutazione finora

- Postmature Infants 1Documento13 paginePostmature Infants 1LyssaMarieKathryneEge100% (1)

- Vesicular MoleDocumento46 pagineVesicular Moledhisazainita0% (1)

- Therapeutic PlayDocumento9 pagineTherapeutic PlayVivek PrabhakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Respiratory Diseases GuideDocumento58 pagineRespiratory Diseases GuideSarahNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Pneumothorax?Documento3 pagineWhat Is Pneumothorax?Santhosh.S.U100% (1)

- Post Partum ComplicationDocumento29 paginePost Partum ComplicationPutri Rizky AmaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nenotal Hypoglycemia and HypocalcemiaDocumento3 pagineNenotal Hypoglycemia and HypocalcemiabhawnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Holistic Nursing CareDocumento14 pagineHolistic Nursing CaremujionoNessuna valutazione finora

- PT Behavioral ProblemsDocumento11 paginePT Behavioral ProblemsAmy LalringhluaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal HypocalcemiaDocumento8 pagineNeonatal HypocalcemiaCristina Fernández ValenciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Harika Priyanka. K Asst. Professor AconDocumento30 pagineHarika Priyanka. K Asst. Professor AconArchana MoreyNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal JaundiceDocumento36 pagineNeonatal JaundiceJenaffer Achamma JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric Liver Transplant AssessmentDocumento30 paginePediatric Liver Transplant AssessmentMadhu Sinha100% (1)

- ON Hemorrhage in Late Pregnancy, Placenta Previa and Abruptio PlacentaDocumento22 pagineON Hemorrhage in Late Pregnancy, Placenta Previa and Abruptio PlacentaReshma AnilkumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Cleft Lip and PalateDocumento2 pagineCleft Lip and PalateTracy100% (1)

- Renal Failure in ChildrenDocumento43 pagineRenal Failure in Childrendennyyy175Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Teaching 4PEUPERAL SEPSISDocumento5 pagineClinical Teaching 4PEUPERAL SEPSISAjit M Prasad PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Cherecteristics of New Born BabyDocumento21 pagineCherecteristics of New Born Babypriyanka bhavsarNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenges of Neonatal Transport in Developing CountriesDocumento19 pagineChallenges of Neonatal Transport in Developing CountriesNeha OberoiNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Pediatric NursingDocumento36 pagineIntroduction To Pediatric Nursingcharan poonia100% (1)

- Newborn CareDocumento49 pagineNewborn CareJohn Mark PocsidioNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Diarrhea: Causes, Symptoms, Prevention and ManagementDocumento12 pagineUnderstanding Diarrhea: Causes, Symptoms, Prevention and ManagementSoumya RajeswariNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses with IMCI GuidelinesDocumento26 pagineManaging Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses with IMCI Guidelinesrakeshr2007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Abnormal Amniotic Fluid LevelsDocumento29 pagineAbnormal Amniotic Fluid LevelsSTAR Plus SerialsNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal Hematologic ConditionsDocumento2 pagineNeonatal Hematologic ConditionsDelphy Varghese100% (1)

- Fetomaternal organ functionsDocumento21 pagineFetomaternal organ functionsAntonela CeremușNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiologic Adaptation of The Newborn and Nursing AssessmentDocumento108 paginePhysiologic Adaptation of The Newborn and Nursing AssessmentRevathi DadamNessuna valutazione finora

- MANAGEMENT OF HYDRAMNIOS AND OLIGOHYDRAMNIOSDocumento12 pagineMANAGEMENT OF HYDRAMNIOS AND OLIGOHYDRAMNIOSEaster Soma HageNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal InfectionsDocumento18 pagineNeonatal InfectionsSanthosh.S.U100% (1)

- 'NicuDocumento12 pagine'NicuTopeshwar TpkNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS)Documento30 pagineIntegrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS)Geeta KumariNessuna valutazione finora

- Antenatal Advices and Minor Disorders of PregnancyDocumento49 pagineAntenatal Advices and Minor Disorders of Pregnancyjeny patelNessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal InfectionsDocumento19 pagineNeonatal InfectionsA B Siddique RiponNessuna valutazione finora

- Exclusive BreastfeedingDocumento11 pagineExclusive BreastfeedingTalitha SalsabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Congenital HyperthyroidismDocumento10 pagineCase Study Congenital HyperthyroidismCamille CaraanNessuna valutazione finora

- Child With Blood DisorderDocumento126 pagineChild With Blood DisorderSivabarathyNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Nurse MidwifeDocumento31 pagineRole of Nurse MidwiferekhamolNessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Scenario, Chapter 45, Nursing Care of A Family When A Child Has A Gastrointestinal DisorderDocumento93 paginePatient Scenario, Chapter 45, Nursing Care of A Family When A Child Has A Gastrointestinal DisorderDay MedsNessuna valutazione finora

- The High Risk New BornDocumento23 pagineThe High Risk New Bornchhaiden100% (4)

- Immediate Newborn Care (Autosaved)Documento183 pagineImmediate Newborn Care (Autosaved)mftaganasNessuna valutazione finora

- Breastfeeding Benefits Infants & MothersDocumento3 pagineBreastfeeding Benefits Infants & MothersArla Donissa-Donique Castillon AlviorNessuna valutazione finora

- Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma TreatmentDocumento4 pagineChildhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma TreatmentMilzan MurtadhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Infant of Diabetic MotherDocumento41 pagineInfant of Diabetic Mothermohdmaghyreh100% (8)

- Seminar ON: Baby Friendly Hospital InitiativeDocumento7 pagineSeminar ON: Baby Friendly Hospital InitiativeUmairah BashirNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Natal CareDocumento94 paginePost Natal CareZekariyas MulunehNessuna valutazione finora

- Ppt-Journal ClubDocumento50 paginePpt-Journal Clubgao1989Nessuna valutazione finora

- Child Health Nursing-I - 201022Documento8 pagineChild Health Nursing-I - 201022ShwetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Preventive 1Documento7 paginePreventive 1Archana Sahu100% (1)

- Malformations of Female Genital OrgansDocumento28 pagineMalformations of Female Genital OrgansTommy SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Care of Child in IncubatorDocumento12 pagineCare of Child in IncubatorSundaraBharathiNessuna valutazione finora

- FEOTAL MEASURE Clinical ParametersDocumento13 pagineFEOTAL MEASURE Clinical Parameterssuman guptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Maternal and Perinatal Outcome in Jaundice Complicating PregnancyDocumento10 pagineMaternal and Perinatal Outcome in Jaundice Complicating PregnancymanognaaaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic - Preventive Pediatrics Subject - Pediatrics Unit - IiDocumento10 pagineTopic - Preventive Pediatrics Subject - Pediatrics Unit - IiDinesh KhinchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Obg Procedures FinalDocumento60 pagineObg Procedures FinalVeena DalmeidaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5 Paediatric Nursing Presentation - 1-1Documento54 pagine1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5 Paediatric Nursing Presentation - 1-1Christina YounasNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ideal Neutropenic Diet Cookbook; The Super Diet Guide To Replenish Overall Health For A Vibrant Lifestyle With Nourishing RecipesDa EverandThe Ideal Neutropenic Diet Cookbook; The Super Diet Guide To Replenish Overall Health For A Vibrant Lifestyle With Nourishing RecipesNessuna valutazione finora

- Drugs Used in Liver DiseaseDocumento17 pagineDrugs Used in Liver Diseaseblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spina BifidaDocumento4 pagineSpina Bifidablast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Neonatal Resuscitation DrugsDocumento4 pagineNeonatal Resuscitation Drugsblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hirscsprung's DiseaseDocumento7 pagineHirscsprung's Diseaseblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Management PrinciplesDocumento7 pagineManagement Principlesblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Seizure Drugs NeonatalDocumento20 pagineSeizure Drugs Neonatalblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rotation PlanDocumento1 paginaRotation Planblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- TAPVCDocumento5 pagineTAPVCblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Family AssessmentDocumento13 pagineFamily Assessmentblast211140% (5)

- Dengue Fever & DSSDocumento14 pagineDengue Fever & DSSblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group DynamicsDocumento12 pagineGroup Dynamicsblast2111100% (1)

- Dengue Fever & DSSDocumento14 pagineDengue Fever & DSSblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Essential Newborn CareDocumento8 pagineEssential Newborn Careblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Child Related LawsDocumento9 pagineChild Related Lawsblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Programmed InstructionDocumento7 pagineProgrammed Instructionblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- EEG WaveformDocumento9 pagineEEG Waveformblast2111Nessuna valutazione finora

- HAP & VAP IDSA Pocketcard Guidelines (2016)Documento12 pagineHAP & VAP IDSA Pocketcard Guidelines (2016)David GerickNessuna valutazione finora

- Indications To Administer Special Tests: (1) Cochlear PathologyDocumento11 pagineIndications To Administer Special Tests: (1) Cochlear PathologyASMAA NOORUDHEENNessuna valutazione finora

- About This Leaflet: FibroadenomaDocumento2 pagineAbout This Leaflet: FibroadenomaEnvhy WinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tle 10Documento49 pagineTle 10peepee poopooNessuna valutazione finora

- BAD Cryotherapy Update March 2018 - Lay Review March 2018Documento4 pagineBAD Cryotherapy Update March 2018 - Lay Review March 2018Mehret TechaneNessuna valutazione finora

- PAVSDMAPCAsDocumento3 paginePAVSDMAPCAsRajesh SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Courvosier Law PDFDocumento6 pagineCourvosier Law PDFElno TatipikalawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathology Outlines - Papillary Carcinoma - GeneralDocumento6 paginePathology Outlines - Papillary Carcinoma - Generalpatka1rNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult Vancomycin Dosing Guidelines DefinitionsDocumento2 pagineAdult Vancomycin Dosing Guidelines DefinitionsPhạm DuyênNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Biology 3Documento42 pagineMedical Biology 3Malik MohamedNessuna valutazione finora

- Wpa 020091Documento1 paginaWpa 020091Dana PascuNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Forensik - Luka TembakDocumento8 pagineJurnal Forensik - Luka Tembakrosa snakNessuna valutazione finora

- Crohn's Disease Case Study: Matt SimsDocumento14 pagineCrohn's Disease Case Study: Matt SimsKipchirchir AbednegoNessuna valutazione finora

- Central Line Removal ProtocolDocumento1 paginaCentral Line Removal Protocolmathurarun2000Nessuna valutazione finora

- Akapulko or Acapulco in English Is A Shrub Found Throughout The PhilippinesDocumento6 pagineAkapulko or Acapulco in English Is A Shrub Found Throughout The PhilippinesJon Adam Bermudez SamatraNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Medical AbbreviationsDocumento10 pagineCommon Medical AbbreviationsPrincess MariscotesNessuna valutazione finora

- Respiratory Diseases of NewbornDocumento93 pagineRespiratory Diseases of NewbornTheva Thy100% (1)

- Contact PrecautionsDocumento2 pagineContact PrecautionsCristina L. JaysonNessuna valutazione finora

- Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Diagnosis & Management: ScopeDocumento19 pagineMajor Depressive Disorder in Adults: Diagnosis & Management: ScopeBadii AmamouNessuna valutazione finora

- Acupressure Points For Relieving ArthritisDocumento18 pagineAcupressure Points For Relieving ArthritisAgustin Benitez Holguin100% (4)

- VAERS Report Details Deaths and Adverse Events Following COVID VaccinesDocumento234 pagineVAERS Report Details Deaths and Adverse Events Following COVID VaccinesbeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Resurgence of TB linked to increased pneumothoraxDocumento5 pagineResurgence of TB linked to increased pneumothoraxM Tata SuhartaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leukemias Nursing ManagementDocumento20 pagineLeukemias Nursing ManagementAnusha Verghese100% (5)

- The Weight of Traditional Therapy in The Management of Chronic Skin Diseases in Donka National HospitalDocumento7 pagineThe Weight of Traditional Therapy in The Management of Chronic Skin Diseases in Donka National HospitalAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNessuna valutazione finora

- Guideline Karsinoma HepatoselulerDocumento11 pagineGuideline Karsinoma HepatoselulerMohammad Ihsan RifasantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Report Employee Training IPCDocumento11 pagineReport Employee Training IPCDandi RawhideNessuna valutazione finora

- Noninvasive Ventilation in Acute Respiratory FailureDocumento6 pagineNoninvasive Ventilation in Acute Respiratory FailureCesar C SNessuna valutazione finora

- The Complete Hematopathology GuideDocumento113 pagineThe Complete Hematopathology GuideJenny SNessuna valutazione finora

- Actea SpicataDocumento4 pagineActea SpicataRaveendra MungaraNessuna valutazione finora

- LoperamideDocumento1 paginaLoperamidekimglaidyl bontuyanNessuna valutazione finora