Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Weld Distortion Control

Caricato da

Maria MantillaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Weld Distortion Control

Caricato da

Maria MantillaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Weld Distortion

Beginning w elders and even those that are more experienced commonly struggle w ith the problem of w eld distortion, (w arping of the base plate caused by heat from the w elding arc). Distortion is troublesome for a number of reasons, but one of the most critical is the potential creation of a w eld that is not structurally sound. This article w ill help to define w hat w eld distortion is and then provide a practical understanding of the causes of distortion, effects of shrinkage in various types of w elded assemblies and how to control it, and finally look at methods for distortion control. What is Weld Distortion? Distortion in a w eld results from the expansion and contraction of the w eld metal and adjacent base metal during the heating and cooling cycle of the w elding process. Doing all w elding on one side of a part w ill cause much more distortion than if the w elds are alternated from one side to the other. During this heating and cooling cycle, many factors affect shrinkage of the metal and lead to distortion, such as physical and mechanical properties that change as heat is applied. For example, as the temperature of the w eld area increases, yield strength, elasticity, and thermal conductivity of the steel plate decrease, w hile thermal expansion and specific heat increase (Fig. 3-1). These changes, in turn, affect heat flow and uniformity of heat distribution.

Fig. 3-1 Changes in the properties of steel w ith increases in temperature complicate analysis of w hat happens during the w elding cycle - and, thus, understanding of the factors contributing to w eldment distortion.

Reasons for Distortion To understand how and w hy distortion occurs during heating and cooling of a metal, consider the bar of steel show n in Fig. 3-2. As the bar is uniformly heated, it expands in all directions, as show n in Fig. 3-2(a). As the metal cools to room temperature it contracts uniformly to its original dimensions.

Fig. 3-2 If a steel bar is uniformly heated w hile unrestrained, as in (a), it w ill expand in all directions and return to its original dimentions on cooling. If restrained, as in (b), during heating, it can expand only in the vertical direction - become thicker. On cooling, the deformed bar contracts uniformly, as show n in (c), and, thus, is permanently deformed. This is a simplified explanation of basic cause of distortion in w elding assemblies.

But if the steel bar is restrained -as in a vise - w hile it is heated, as show n in Fig. 3-2(b), lateral expansion cannot take place. But, since volume expansion must occur during the heating, the bar expands in a vertical direction (in thickness) and becomes thicker. As the deformed bar returns to room temperature, it w ill still tend to contract uniformly in all directions, as in Fig. 3-2 (c). The bar is now shorter, but thicker. It has been permanently deformed, or distorted. (For simplification, the sketches show this distortion occurring in thickness only. But in actuality, length is similarly affected.) In a w elded joint, these same expansion and contraction forces act on the w eld metal and on the base metal. As the w eld metal solidifies and fuses w ith the base metal, it is in its maximum expanded from. On cooling, it attempts to contract to the volume it w ould normally occupy at the low er temperature, but it is restrained from doing so by the adjacent base metal. Because of this, stresses develop w ithin the w eld and the adjacent base metal. At this point, the w eld stretches (or yields) and thins out, thus adjusting to the volume requirements of the low er temperature. But only those stresses that exceed the yield strength of the w eld metal are relieved by this straining. By the time the w eld reaches room temperature - assuming complete restraint of the base metal so that it cannot move - the w eld w ill contain locked-in tensile stresses approximately equal to the yield strength of the metal. If the restraints (clamps that hold the w orkpiece, or an opposing shrinkage force) are removed, the residual stresses are partially relieved as they cause the base metal to move, thus distorting the w eldment.

Shrinkage Control - What You Can Do to Minimize Distortion

To prevent or minimize w eld distortion, methods must be used both in design and during w elding to overcome the effects of the heating and cooling cycle. Shrinkage cannot be prevented, but it can be controlled. Several w ays can be used to minimize distortion caused by shrinkage: 1. Do not overw eld The more metal placed in a joint, the greater the shrinkage forces. Correctly sizing a w eld for the requirements of the joint not only minimizes distortion, but also saves w eld metal and time. The amount of w eld metal in a fillet w eld can be minimized by the use of a flat or slightly convex bead, and in a butt joint by proper edge preparation and fitup. The excess w eld metal in a highly convex bead does not increase the allow able strength in code w ork, but it does increase shrinkage forces. When w elding heavy plate (over 1 inch thick) bevelling or even double bevelling can save a substantial amount of w eld metal w hich translates into much less distortion automatically. In general, if distortion is not a problem, select the most economical joint. If distortion is a problem, select either a joint in w hich the w eld stresses balance each other or a joint requiring the least amount of w eld metal. 2. Use interm ittent w elding Another w ay to minimize w eld metal is to use intermittent rather than continuous w elds w here possible, as in Fig. 3-7(c). For attaching stiffeners to plate, for example, intermittent w elds can reduce the w eld metal by as much as 75 percent yet provide the needed strength.

Fig. 3-7 Distortion can be prevented or minimized by techniques that defeat - or use constructively - the effects of the heating and cooling cycle.

3. Use as few w eld passes as possible Few er passes w ith large electrodes, Fig. 3-7(d), are preferable to a greater number of passes w ith small electrodes w hen transverse distortion could be a problem. Shrinkage caused by each pass tends to be cumulative, thereby increasing total shrinkage w hen many passes are used. 4. Place w elds near the neutral axis Distortion is minimized by providing a smaller leverage for the shrinkage forces to pull the plates out of alignment. Figure 3-7(e) illustrates this. Both design of the w eldment and w elding sequence can be used effectively to control distortion.

Fig. 3-7 Distortion can be prevented or minimized by techniques that defeat - or use constructively - the effects of the heating and cooling cycle.

5. Balance w elds around the neutral axis This practice, show n in Fig. 3-7(f), offsets one shrinkage force w ith another to effectively minimize distortion of the w eldment. Here, too, design of the assembly and proper sequence of w elding are important factors. 6. Use backstep w elding In the backstep technique, the general progression of w elding may be, say, from left to right, but each bead segment is deposited from right to left as in Fig. 37(g). As each bead segment is placed, the heated edges expand, w hich temporarily separates the plates at B. But as the heat moves out across the plate to C, expansion along outer edges CD brings the plates back together. This separation is most pronounced as the first bead is laid. With successive beads, the plates expand less and less because of the restraint of prior w elds. Backstepping may not be effective in all applications, and it cannot be used economically in automatic w elding.

Fig. 3-7 Distortion can be prevented or minimized by techniques that defeat - or use constructively - the effects of the heating and cooling cycle.

7. Anticipate the shrinkage forces Presetting parts (at first glance, I thought that this w as referring to overhead or vertical w elding positions, w hich is not the case) before w elding can make shrinkage perform constructive w ork. Several assemblies, preset in this manner, are show n in Fig. 3-7(h). The required amount of preset for shrinkage to pull the plates into alignment can be determined from a few trial w elds. Prebending, presetting or prespringing the parts to be w elded, Fig. 3-7(i), is a simple example of the use of opposing mechanical forces to counteract distortion due to w elding. The top of the w eld groove - w hich w ill contain the bulk of the w eld metal - is lengthened w hen the plates are preset. Thus the completed w eld is slightly longer than it w ould be if it had been made on the flat plate. When the clamps are released after w elding, the plates return to the flat shape, allow ing the w eld to relieve its longitudinal shrinkage stresses by shortening to a straight line. The tw o actions coincide, and the w elded plates assume the desired flatness. Another common practice for balancing shrinkage forces is to position identical w eldments back to back, Fig. 3-7(j), clamping them tightly together. The w elds are

completed on both assemblies and allow ed to cool before the clamps are released. Prebending can be combined w ith this method by inserting w edges at suitable positions betw een the parts before clamping. In heavy w eldments, particularly, the rigidity of the members and their arrangement relative to each other may provide the balancing forces needed. If these natural balancing forces are not present, it is necessary to use other means to counteract the shrinkage forces in the w eld metal. This can be accomplished by balancing one shrinkage force against another or by creating an opposing force through the fixturing. The opposing forces may be: other shrinkage forces; restraining forces imposed by clamps, jigs, or fixtures; restraining forces arising from the arrangement of members in the assembly; or the force from the sag in a member due to gravity. 8. Plan the w elding sequence A w ell-planned w elding sequence involves placing w eld metal at different points of the assembly so that, as the structure shrinks in one place, it counteracts the shrinkage forces of w elds already made. An example of this is w elding alternately on both sides of the neutral axis in making a complete joint penetration groove w eld in a butt joint, as in Fig. 3-7(k). Another example, in a fillet w eld, consists of making intermittent w elds according to the sequences show n in Fig. 3-7(l). In these examples, the shrinkage in w eld No. 1 is balanced by the shrinkage in w eld No. 2.

Fig. 3-7 Distortion can be prevented or minimized by techniques that defeat - or use constructively - the effects of the heating and cooling cycle.

Clamps, jigs, and fixtures that lock parts into a desired position and hold them until w elding is finished are probably the most w idely used means for controlling distortion in small assemblies or components. It w as mentioned earlier in this section that the restraining force provided by clamps increases internal stresses in the w eldment until the yield point of the w eld metal is reached. For typical w elds on low -carbon plate, this stress level w ould approximate 45,000 psi. One might expect this stress to cause considerable movement or distortion after the w elded part is removed from the jig or clamps. This does not occur, how ever, since the strain (unit contraction) from this stress is very low compared to the amount of movement that w ould occur if no restraint w ere used during w elding. 9. Rem ove shrinkage forces after w elding Peening is one w ay to counteract the shrinkage forces of a w eld bead as it cools. Essentially, peening the bead stretches it and makes it thinner, thus relieving (by plastic deformation) the stresses induced by contraction as the metal cools. But this method must be used w ith care. For example, a root bead should never be peened, because of the danger of either concealing a crack or causing one. Generally, peening is not permitted on the final pass, because of the possibility of covering a crack and interfering w ith inspection, and because of the undesirable w ork-hardening effect. Thus, the utility of the technique is limited, even though there have been instances w here betw een-pass peening proved to be the only solution for a distortion or cracking problem. Before peening is used on a job, engineering approval should be obtained. Another method for removing shrinkage forces is by thermal stress relieving - controlled heating of the w eldment to an elevated temperature, follow ed by controlled cooling. Sometimes tw o identical w eldments are clamped back to back, w elded, and then stress-relieved w hile being held in this straight condition. The residual stresses that w ould tend to distort the w eldments are thus minimized. 10. Minim ize w elding tim e Since complex cycles of heating and cooling take place during w elding, and since time is required for heat transmission, the time factor affects distortion. In general, it is desirable to finish the w eld quickly, before a large volume of surrounding metal heats up and expands. The w elding process used, type and size of electrode, w elding current, and speed of travel, thus, affect the degree of shrinkage and distortion of a w eldment. The use of mechanized w elding equipment reduces w elding time and the amount of metal affected by heat and, consequently, distortion. For example, depositing a given-size w eld on thick plate w ith a process operating at 175 amp, 25 volts, and 3 ipm requires 87,500 joules of energy per linear inch of w eld (also know n as heat input). A w eld w ith approximately the same size produced w ith a process operating at 310 amp, 35 volts, and 8 ipm requires 81,400 joules per linear inch. The w eld made w ith the higher heat input generally results in a greater amount of distortion. (note: I don't w ant to use the w ords "excessive" and "more than necessary" because the w eld size is, in fact, tied to the heat input. In general, the fillet w eld size (in inches) is equal to the square root of the quantity of the heat input (kJ/in) divided by 500. Thus these tw o w elds are most likely not the same size.

Other Techniques for Distortion Control

Water-Cooled Jig Various techniques have been developed to control distortion on specific w eldments. In sheet-metal w elding, for example, a w ater-cooled jig (Fig. 3-33) is useful to carry heat aw ay from the w elded components. Copper tubes are brazed or soldered to copper holding clamps, and the w ater is circulated through the tubes during w elding. The restraint of the clamps also helps minimize distortion.

Fig. 3-33 A w ater-cooled jig for rapid removal of heat w hen w elding sheet meta.

Strongback The "strongback" is another useful technique for distortion control during butt w elding of plates, as in Fig. 3-34(a). Clips are w elded to the edge of one plate and w edges are driven under the clips to force the edges into alignment and to hold them during w elding.

Fig. 3-34 Various strongback arrangements to control distortion during butt-w elding.

Therm al Stress Relieving Except in special situations, stress relief by heating is not used for correcting distortion. There are occasions, how ever, w hen stress relief is necessary to prevent further distortion from occurring before the w eldment is finished. Sum m ary: A Checklist to Minim ize Distortion Follow this checklist in order to minimize distortion in the design and fabrication of w eldments: Do not overw eld Control fitup Use intermittent w elds w here possible and consistent w ith design requirements Use the smallest leg size permissible w hen fillet w elding For groove w elds, use joints that w ill minimize the volume of w eld metal. Consider double-sided joints instead of single-sided joints Weld alternately on either side of the joint w hen possible w ith multiple-pass w elds Use minimal number of w eld passes Use low heat input procedures. This generally means high deposition rates and higher travel speeds Use w elding positioners to achieve the maximum amount of flat-position w elding. The flat position permits the use of large-diameter electrodes and highdeposition-rate w elding procedures Balance w elds about the neutral axis of the member Distribute the w elding heat as evenly as possible through a planned w elding sequence and w eldment positioning Weld tow ard the unrestrained part of the member Use clamps, fixtures, and strongbacks to maintain fitup and alignment Prebend the members or preset the joints to let shrinkage pull them back into alignment Sequence subassemblies and final assemblies so that the w elds being made continually balance each other around the neutral axis of the section

Follow ing these techniques w ill help minimize the effects of distortion and residual stresses.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Fatigue AssignmentDocumento10 pagineFatigue Assignmentnelis010% (1)

- HPDC Design TolerancesDocumento15 pagineHPDC Design Toleranceskarthik100% (1)

- MAT E 202 - Final Exam NotesDocumento16 pagineMAT E 202 - Final Exam NotesjordhonNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheet Metal FabricationDocumento70 pagineSheet Metal Fabricationnjsoffice33% (6)

- Weld DistortionDocumento5 pagineWeld DistortionNSunNessuna valutazione finora

- Weld Distortion: Application Stories Process and Theory Welding How-To'S Welding Projects Welding Solutions YoutubeDocumento12 pagineWeld Distortion: Application Stories Process and Theory Welding How-To'S Welding Projects Welding Solutions Youtubevampiredraak2712Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hossam Mahmoud Ahmed No. 28: Faculty of Engineering. Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering DepartmentDocumento14 pagineHossam Mahmoud Ahmed No. 28: Faculty of Engineering. Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering Department5030099Nessuna valutazione finora

- Prevention and Control of Weld DistortionDocumento7 paginePrevention and Control of Weld DistortionHouman HatamianNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevention and Control of Weld Distortion: Print This PageDocumento6 paginePrevention and Control of Weld Distortion: Print This PageNguyễn Hữu TrungNessuna valutazione finora

- Expansion and ContractionDocumento5 pagineExpansion and ContractionSanda Catalina IoanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.3. Residual Stresses and Distortion in WeldmentsDocumento11 pagine4.3. Residual Stresses and Distortion in WeldmentsprokulisNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Control The Warping of Parts in Thin SheetDocumento6 pagineHow To Control The Warping of Parts in Thin SheetNeil WayneNessuna valutazione finora

- Welding Distortion and Warpage: June 13, 2022 byDocumento20 pagineWelding Distortion and Warpage: June 13, 2022 byArnab Goswami100% (1)

- Distortion Prevent and ControlDocumento14 pagineDistortion Prevent and ControlTheAnh TranNessuna valutazione finora

- RESIDUAL STRESSES, Distortion and Weld Defects DISTORTION & WELD DEFECTSDocumento18 pagineRESIDUAL STRESSES, Distortion and Weld Defects DISTORTION & WELD DEFECTSManoj NirgudeNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 12 Residual Stresses, Distortion & Weld Defects: StructureDocumento18 pagineUnit 12 Residual Stresses, Distortion & Weld Defects: StructureMohammed AshiqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2Documento6 pagineChapter 2udomNessuna valutazione finora

- Fatigue TestingDocumento10 pagineFatigue TestingMuhammed SulfeekNessuna valutazione finora

- Residual StressDocumento10 pagineResidual StressbalamuruganNessuna valutazione finora

- Weld Poster ExplainationDocumento2 pagineWeld Poster ExplainationDaniel ThamNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 What Causes Distortion?: Longitudinal ShrinkageDocumento21 pagine1 What Causes Distortion?: Longitudinal Shrinkage4romi89Nessuna valutazione finora

- DistortionDocumento18 pagineDistortionSteransko100% (1)

- Kuliah Ke-9 Strengthening MechanismDocumento48 pagineKuliah Ke-9 Strengthening MechanismNixonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fab 02 Module 18 - FAB 2 - Welding Stresses, Distortion, Residual Stress - Repair Welding.Documento26 pagineFab 02 Module 18 - FAB 2 - Welding Stresses, Distortion, Residual Stress - Repair Welding.Raghu vamshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 5 - DistortionDocumento22 pagineLesson 5 - DistortionKhepa BabaNessuna valutazione finora

- TGN-D-04 Distortion Control in ShipbuildingDocumento9 pagineTGN-D-04 Distortion Control in ShipbuildingKomkamol ChongbunwatanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Reduction of Residual StressDocumento19 pagineReduction of Residual StressSteve HornseyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ductile Fracture WhitepaperDocumento9 pagineDuctile Fracture WhitepaperaoliabemestreNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Die Maintenance Handbook Chapter 12 PDFDocumento17 pagine7 Die Maintenance Handbook Chapter 12 PDFAtthapol YuyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Miller - 2010 Welding Heavy Structural Steel SucessfulyyDocumento15 pagineMiller - 2010 Welding Heavy Structural Steel SucessfulyyLleiLleiNessuna valutazione finora

- CE 501 - Steel - SasheenDocumento12 pagineCE 501 - Steel - SasheenSasheen Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Residual StressDocumento21 pagine10 Residual StressAlaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aug10 SteeSteellwise WebDocumento3 pagineAug10 SteeSteellwise Webeng_ahmed_666Nessuna valutazione finora

- Welding Steel and TankDocumento39 pagineWelding Steel and Tankprasanth bhadranNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of WeldingDocumento13 paginePrinciples of WeldingMadhurimaMitraNessuna valutazione finora

- Material ScienceDocumento13 pagineMaterial ScienceolingxjcNessuna valutazione finora

- Distortion WELDINGDocumento106 pagineDistortion WELDINGshruthi100% (1)

- Draft Strain HardeningDocumento9 pagineDraft Strain HardeningRho AsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheet-Metalworking ProcessesDocumento10 pagineSheet-Metalworking ProcessesSalih Burak GÜLENNessuna valutazione finora

- 17-Residual Stress and DistortionDocumento20 pagine17-Residual Stress and DistortionSaif UllahNessuna valutazione finora

- Distortion in Aluminum Welded StructuresDocumento3 pagineDistortion in Aluminum Welded StructuresRaron1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Twi Fatigure TestingDocumento13 pagineTwi Fatigure TestingchungndtNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.sumitomo Servicing Know How PDFDocumento37 pagine4.sumitomo Servicing Know How PDFsurianto100% (1)

- Distortion - Types and CausesDocumento3 pagineDistortion - Types and CausesFsNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambering BeamsDocumento7 pagineCambering BeamsskidbarNessuna valutazione finora

- Metal BehaviourDocumento12 pagineMetal BehaviourVeeraraj AlagarsamyNessuna valutazione finora

- Residual Stresses in Weld JointsDocumento8 pagineResidual Stresses in Weld Jointshayder1920Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elimination of Bowing Distortion in Welded StiffenersDocumento8 pagineElimination of Bowing Distortion in Welded StiffenersHaris HartantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Deformation of MetalDocumento23 pagineDeformation of MetalVarun SinghalNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheet Metal FabricationDocumento70 pagineSheet Metal Fabricationhsemarg100% (5)

- Dislocation Theory: Dislocations and Strengthening MechanismsDocumento4 pagineDislocation Theory: Dislocations and Strengthening MechanismsgunapalshettyNessuna valutazione finora

- 03-Manufacturing Properties of MetalsDocumento50 pagine03-Manufacturing Properties of Metalsqwerrty465Nessuna valutazione finora

- Paper From SDI (Structural Deck Institute) WWDocumento9 paginePaper From SDI (Structural Deck Institute) WWkiss_59856786Nessuna valutazione finora

- IWE4-3 - Residual StressesDocumento16 pagineIWE4-3 - Residual StressesIrmantas ŠakysNessuna valutazione finora

- Modulo 4 CM 19 09 2020Documento25 pagineModulo 4 CM 19 09 2020carlomonsalve1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Friction Stir Welding of High Strength 7XXX Aluminum AlloysDa EverandFriction Stir Welding of High Strength 7XXX Aluminum AlloysNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress in ASME Pressure Vessels, Boilers, and Nuclear ComponentsDa EverandStress in ASME Pressure Vessels, Boilers, and Nuclear ComponentsNessuna valutazione finora

- Elementary Mechanics of Solids: The Commonwealth and International Library: Structure and Solid Body MechanicsDa EverandElementary Mechanics of Solids: The Commonwealth and International Library: Structure and Solid Body MechanicsNessuna valutazione finora

- Scientific American Supplement, No. 392, July 7, 1883Da EverandScientific American Supplement, No. 392, July 7, 1883Nessuna valutazione finora

- Creating High Quality Stick WeldsDocumento2 pagineCreating High Quality Stick WeldsMaria MantillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Instrument Manifold Valves 5000Documento16 pagineInstrument Manifold Valves 5000Maria MantillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Piping Design InfoDocumento265 paginePiping Design InfoPedro Luis Choque MamaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Technological Advances in Steels Heat Treatment: Izabel Fernanda MachadoDocumento5 pagineTechnological Advances in Steels Heat Treatment: Izabel Fernanda MachadoMaria MantillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural Steels: Effect of Alloying Elements and Structure On The Properties of Low-Carbon Heat-Treatable SteelDocumento5 pagineStructural Steels: Effect of Alloying Elements and Structure On The Properties of Low-Carbon Heat-Treatable SteelMaria MantillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Activated Carbon From Corn CobDocumento7 pagineActivated Carbon From Corn CobJhen DangatNessuna valutazione finora

- Energy Conservation in Pumping SystemDocumento33 pagineEnergy Conservation in Pumping SystemFahad KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ex6 Peroxide ValueDocumento7 pagineEx6 Peroxide ValueChidi IfenweobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Artigo Kaolinite Review - Intercalation and Production of PolymerDocumento17 pagineArtigo Kaolinite Review - Intercalation and Production of PolymerPhelippe SousaNessuna valutazione finora

- High-Energy Cathode Materials (Li Mno Limo) For Lithium-Ion BatteriesDocumento13 pagineHigh-Energy Cathode Materials (Li Mno Limo) For Lithium-Ion BatteriesEYERUSALEM TADESSENessuna valutazione finora

- Psa Nitrogen GeneratorDocumento7 paginePsa Nitrogen GeneratorFarjallahNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety Data Sheet PropanDocumento9 pagineSafety Data Sheet PropanFahri SofianNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 10 NoPWDocumento34 pagineChapter 10 NoPWArjun PatelNessuna valutazione finora

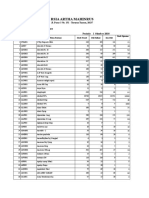

- Rsia Artha Mahinrus: Jl. Pasar 3 No. 151 - Terusan Tuasan, 20237Documento15 pagineRsia Artha Mahinrus: Jl. Pasar 3 No. 151 - Terusan Tuasan, 20237Rabyatul Maulida NasutionNessuna valutazione finora

- EDF SK 1-1 - 1HYB800001-090B (Latest)Documento130 pagineEDF SK 1-1 - 1HYB800001-090B (Latest)ashton.emslieNessuna valutazione finora

- Supercritical Uid Extraction of Spent Coffee Grounds - Measurement of Extraction Curves and Economic AnalysisDocumento10 pagineSupercritical Uid Extraction of Spent Coffee Grounds - Measurement of Extraction Curves and Economic AnalysisMarcelo MeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Standards For Pesticide Residue Limits in Foods PDFDocumento180 pagineStandards For Pesticide Residue Limits in Foods PDFNanette DeinlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Colorado Potato Beetle: LeptinotarsaDocumento13 pagineColorado Potato Beetle: Leptinotarsaenzo abrahamNessuna valutazione finora

- Fire HazardDocumento65 pagineFire HazardRohit Sharma75% (4)

- SCK SeriesDocumento17 pagineSCK SeriestahirianNessuna valutazione finora

- Arc 1st Mod Arch 503 Building Services Question Bank 15 Mark QuestionsDocumento33 pagineArc 1st Mod Arch 503 Building Services Question Bank 15 Mark QuestionsVictor Deb RoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Paints Pigments and Industrial CoatingsDocumento10 paginePaints Pigments and Industrial CoatingsRaymond FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- Phyto-Mediated Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles of BerberisDocumento31 paginePhyto-Mediated Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles of BerberisRabeea NasirNessuna valutazione finora

- Open Test Series - Paper-1 - (21-09-2021)Documento31 pagineOpen Test Series - Paper-1 - (21-09-2021)Yogesh KhatriNessuna valutazione finora

- AccQ Tag SolutionDocumento1 paginaAccQ Tag SolutionNgọc Việt NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Enthusiast Score-I 2021-22Documento1 paginaEnthusiast Score-I 2021-22Aarya Vardhan ShandilyaNessuna valutazione finora

- ACD/Percepta: Overview of The ModulesDocumento91 pagineACD/Percepta: Overview of The ModulesTinto J AlencherryNessuna valutazione finora

- Alccofine 1108SRDocumento2 pagineAlccofine 1108SRLaxmana PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrochemistry Formula SheetDocumento25 pagineElectrochemistry Formula SheetanonymousNessuna valutazione finora

- QM-I ManualDocumento87 pagineQM-I ManualMuhammad Masoom AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- BIOCHEMDocumento3 pagineBIOCHEMLeighRence BaltazarNessuna valutazione finora

- FastenersDocumento178 pagineFastenersthulasi_krishna100% (6)

- Mndy ParchiDocumento858 pagineMndy ParchiPAN SERVICESNessuna valutazione finora

- Gek105060 File0060Documento12 pagineGek105060 File0060Mauricio GuanellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Equalization Tank-Homogenization TankDocumento16 pagineEqualization Tank-Homogenization TankAnusha GsNessuna valutazione finora