Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Legal Research

Caricato da

Mariam BautistaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Legal Research

Caricato da

Mariam BautistaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

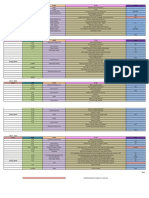

BROWN ET AL. VS. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA ET AL.

, KANSAS FACTS: Minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a non-segregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a threejudge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the socalled "separate but equal" doctrine announced by the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (163 U.S. 537). Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case, the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools. An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment's history, with respect to segregated schools, is the status of public education at that time. Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost non-existent, and practically all of them were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences as well as in the business and professional world. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (305 U.S. 337); Sipuel v. Oklahoma, (332 U.S. 631); Sweatt v. Painter, (339 U.S. 629); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, (339 U.S. 637). In none of these cases was it necessary to re-examine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education. In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter, there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other "tangible" factors. The Courts decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. Rather, they must look further into the effect of segregation itself on public education. ISSUE Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? HELD: Court believes that it does deprive children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities. In approaching this problem, the Court deemed that it was inappropriate and inconclusive to rule on the basis of conditions existing in 1868 when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, or even in 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson (Separate but equal doctrine) was written. It automatically becomes an exception with regards to adherence to past precedents or Stare Decisis, for the very reason that what was deemed applicable then, may not necessarily be applicable now. The times are different as well as the conditions and circumstances present in the current Educational system. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws. Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or

requiring such segregation, denies or deprives children of the minority group the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment - even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. The Court concludes that in the field of public education the doctrine of "Separate but Equal" applied in Plessy vs. Ferguson has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. COMPARISONS: IN US: July 28, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment gave a new sense of hope and inspiration to a once oppressed people. It was conceived to be the foundation for restoring America to its great status and prosperity. Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Additional: The Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) of 1974 is a federal law of the United States of America. It prohibits discrimination against faculty, staff and students, including racial segregation of students, and requires school districts to take action to overcome barriers to students' equal participation. It is one of a number of laws affecting educational institutions including the Rehabilitation Act (1973), Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). IN RP: Equal Protection Clause Concept: -Those who have less in life should have more in law to give them a better chance at competing with those who have more in life. Simply means equality in the enjoyment of similar rights and privileges granted by law Reference: Philippine Government and Constitution by Albano. Bill of Rights: Bundle of rights guarantees the preservation of our natural rights. Bill of Rights 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION ARTICLE III, BILL OF RIGHTS Section 1. No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws. Marbury vs Madison FACTS: Establishing 10 new district courts. Expanding the number of circuit courts from three to six. Adding additional judges to each circuit. Giving President the authority to appoint Federal Judges and Justices of the Peace. It also reduced the number of Supreme Court Justices from six to five, effective upon the next vacancy in the Court. Judiciary Act of 1801 took effect in February 1801.

Midnight judges

John Adams, by the end of his term appointed; 16 Federalist Circuit Judges 42 Federalist Justices of Peace They were all located in the Washington and Alexandria Area. Appointments were then consented, approved, signed and sealed by the Senate. In order to assume the office, and appointments to go into effect, the Commissions must be delivered to those appointed. Majority of the Commissions were delivered but it was impossible for all to be delivered before the end of John Adams term. Mar. 4,1801 Thomas Jefferson assumed position as President of the United States of America. As soon as he was able, he ordered not to deliver the remaining commissions. Jeffersons opinion that the undelivered commissions, not having been delivered on time, were void. Without the commissions the appointees were unable to assume the offices and duties to which they had been appointed. William Marbury, filed in the US Supreme Court a petition to award a Writ of Mandamus to the, now, Secretary of State, James Madison. ISSUE: Questions raised; (1) Whether the Supreme Court can award Writ of Mandamus in any case. (2) Whether it will lie to a Secretary of State, in any case whatsoever. (3) Whether in the present case, the court may award a mandamus to James Madison, Secretary of State. HELD: In deciding, the court considered the following questions; (a) Did Marbury have a right to the Commission? (b) Do the laws of the country give Marbury a legal remedy? (c) Is asking the Supreme Court for a Writ of Mandamus the correct legal remedy? GROUP 4 MEMBERS: LEGAL RESEARCH SEPT. 19, 2011 ZORILLA, RITCHELLE MEJOR, GERARD SARSONAS, JOHNSON RAMOS, ABRAHAM (1A)

prosecuted and punished as if he were the principal offender. The appellants contend that the accessory statute applied violated the Fourteenth Amendment. They raised the constitutional rights of the married people with whom they had a professional relationship. The appellants were found guilty as accessories and fined $100 each. The Appellate Division of the Circuit Court and Supreme Court of Errors affirmed the judgment of the lower court.

Issue: Whether or not, Sec. 53-32 and 54-196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut, which forbid the use of contraceptives, violate the Constitution particularly the right to privacy of the married persons. Legal standing of the appellants: The US Supreme Court paralleled the situation to the cases Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33, where an employee was permitted to assert the rights of his employer; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, where the owners of private schools were entitled to assert the rights of potential pupils and their parents; and etc. The Court recognized probable jurisdiction. The Courts reason for recognizing the legal standing of the appellants is that the appellants are in the defense of a criminal conviction for serving married couples in a violation of an aiding-and-abetting statute. Certainly the accessory should have standing to assert that the offense which he is charges with assisting is not, or cannot constitutionally be, a crime. Moreover, the rights of husband and wife, pressed here, are likely to be diluted or adversely affected unless those rights are considered in a suit involving those who have this kind of confidential relation to them. Thus, the Appellants Griswold and Buxton have legal standing in the case to raise the constitutional rights of the married people with whom they had a professional relationship. Held: Yes. Specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance. Various guarantees create zones of privacy. The right of association contained in the penumbra of the First Amendment is one. The Third Amendment in its prohibition against the quartering of soldiers in any house in time of peace without the consent of the owner is another facet of that privacy. The Fourth Amendment explicitly affirms the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Fifth Amendment in its Self-Incrimination Clause enables the citizen to create a zone of privacy which the government may not force him to surrender to his detriment. The Ninth Amendment provides: The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. The Fourth and Fifth Amendments were described as protection against all governmental invasions of the sanctity of a mans home and the privacies of life. We referred to the Fourth Amendment as creating a right to privacy, no less important than any other right carefully and particularly reserved to the people. The present case concerns a relationship lying within the zone of privacy created by several fundamental guarantees. And it concerns a law which, in forbidding the use of contraceptives rather than regulating their manufacture or sale, seeks to achieve its goals by means having a maximum destructive impact upon that relationship. Such a law cannot stand in light of the familiar principle, so often applied by this Court, that a "governmental purpose to control or prevent activities constitutionally subject to state regulation may not

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) Facts: Appellant Griswold, Executive Director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut and Co-appellant Buxton, a licensed physician and a professor at the Yale Medical School who served as Medical director for the League at its center in New Haven, gave information, instruction and medical advice to married persons as to the means of preventing conception, from Nov. 1-10, 1961. The appellants were arrested for violating Sec. 53-32 and 54196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut. Sec 53-32 provides: any person who uses any drug, medicinal article or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception shall be fined not less than $50 or imprisoned not less than 60 days nor more than 1 year or be both fined and imprisoned. Sec. 54-196 provides: any person who assists, abets, counsels, hires, or commands another to commit any offense may be

be achieved by means which sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby invade the area of protected freedoms." Would we allow the police to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives? The very idea is repulsive to the notions of privacy surrounding the marriage relationship. We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions. APPELLANTS HAVE STANDING TO ASSERT THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS OF THE MARRIED PEOPLE. THE CONNECTICUT STATUTE FORBIDDING USE OF CONTRACEPTIVES VIOLATES THE RIGHT OF MARITAL PRIVACY WHICH IS WITHIN THE PENUMBRA OF SPECIFIC GUARANTEES OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS. CONNECTICUT SUPREME COURT OF ERROR (151 CONN. 544, 200 A.2D 479) REVERSED.

Phiippines v. Zamora, 338 SCRA 81; Abaya v. Ebdane, Jr., 515 SCRA 720.) Further, before the court may resolve the question of constitutionality of a statute, the following requisites should, as a rule, be present (Agpalo, Statutory Construction, citing Dumlao v. Commision on Elections, G.R. No. 52245): 1. The existence of an appropriate case. The case is an appropriate case since the Appellants Griswold and Buxton raise a justiciable controversy wherein the resolution of which the court will have to choose the Constitution and the challenged Sec. 53-32 and 54-196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut. An interest personal and substantial by the party raising the constitutional question. The Appellants Griswold and Buxton have an interest personal and substantial since by attacking the constitutionality of Sec. 53-32 and 54196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut, they may: (1) obtain vindication, and (2) protect the rights of the married people whom they had professional relationship with. The plea that the function be exercised at the earliest opportunity. The Appellants on their defense against conviction raised the plea that the accessory statute Sec. 54-196 as well as the 53-32 are unconstitutional in the Connecticut Circuit Court, though Appellate Division of Circuit Court and Supreme Court of Errors affirmed the judgment. The necessity that the constitutional question be passed upon in order to decide the case. The constitutional question needs to be passed upon to validate whether conviction of the Appellants is proper. Thus, Appellants Griswold and Buxton have the legal standing to raise the issue of constitutionality of Sec. 53-32 and 54-196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut. Filipinized Held: Yes. Our 1987 Constitution also provides for zones of privacy. The case of Sabio v. Gordon (G.R. No. 174340, October 17, 2006) recognizes the zones of privacy stating that: Zones of privacy are recognized and protected in our laws. Within these zones, any form of intrusion is impermissible unless excused by law and in accordance with customary legal process. The meticulous regard we accord to these zones arises not only from our conviction that the right to privacy is a constitutional right and the right most valued by civilized men, but also from our adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which mandates that, no one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy and everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. Further, it was identified that: Our Bill of Rights, enshrined in Article III of the Constitution, provides at least two guarantees that explicitly create zones of privacy. It highlights a persons right to be let alone or the right to determine what, how much, to whom and when information about himself shall be disclosed. Section 2 guarantees the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures of whatever nature and for any purpose. Section 3 renders inviolable the privacy of communication and correspondence and further cautions that any evidence obtained in violation of this or the preceding section shall be inadmissible for any purpose in any proceeding. However, this right to privacy was also identified to be limited to: In evaluating a claim for violation of the right to privacy a court must determine whether a person has exhibited a reasonable expectation of 4. 3. 2.

Concurring opinions: 1. Justice Goldberg -believes that the right of privacy in marital relation is fundamental and basic a personal right retained by the people within the meaning of the Ninth Amendment. 2. Justice Harlan - believes that the Connecticut statute infringes the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because the enactment violates basic values implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. 3. Justice White -believes that the Connecticut law as applied to married couples deprives them of liberty without due process of law, as that concept is used in the Fourteenth Amendment. The telling effect of the Connecticut statute on the freedoms of married persons deprives such persons of liberty without due process of law. Dissenting opinions: 1. Justice Black -believes that the Connecticut statute is not forbidden by any provision of the Federal Constitution as that Constitution was written. 2. Justice Stewart -forwards that the Connecticut law which forbids the use of contraceptives by anyone, although is an uncommonly silly law does not violate the Constitution.

Legal Standing of the appellants (Filipinized): Legal Standing or locus standi is a right of appearance in a court of justice on a given question a partys personal and substantial interest in a case such that he has sustained or will sustain direct injury as a result of the governmental act being challenged. The term interest means a material interest, an interest in issue affected by the decree, as distinguished from the interest in the question involved, or a mere incidental interest. The gist of the question of standing is whether a party alleges such personal stake in the outcome of the controversy as to assure concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of issues upon which the court depends for illumination of difficult constitutional question. (Integrated Bar of the

privacy and, if so, whether that expectation has been violated by unreasonable government intrusion. The concept of right to privacy is recognized and enshrined in several provisions of our 1987 Constitution. It is recognized in the Art. III or the Bill of Rights particularly Sec.1 which provides: no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of laws; Sec. 2 which provides: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable seizures of whatever nature and for any purpose shall be inviolable, and no search warrant or warrant of arrest shall issue except upon probable cause to be determined personally by the judge after examination under oath or affirmation of the complainant and the witnesses he may produce, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized; Sec. 3 which provides: the privacy of communication and correspondence shall be inviolable except upon lawful order of the court, or when public safety or order requires otherwise as prescribed by law; Sec. 6 which provides: The liberty of abode and of changing the same within the limits prescribed by law shall not be impaired except upon lawful order of the court. Neither shall the right to travel be impaired except in the interest of national security, public safety, or public health, as may be provided by law; Sec. 8 which provides: The right of the people, including those employed in the public and private sectors, to form unions, associations, or societies for purposes not contrary to law shall not be abridged; and Sec. 17 which provides: no person shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. (Albano, Philippine Government and Constitution) Zones of privacy are likewise recognized and protected in our laws. One example is Art. 26 of the New Civil Code which provides that every person shall respect the dignity, personality, privacy and peace of mind of his neighbors and other persons and punishes as actionable torts several acts by a person of meddling and prying into the privacy of another. The right to privacy is founded on a persons inherent right to enjoy private life without having incidents thereto made public. It is considered as a right to live as one chooses, but of course it is not an absolute right. (Albano, Philippine Government and Constitution) In addition, concurring to the idea of Justice Harlan and Justice White in their idea of the Fourteenth Amendment (Due Process Clause), our 1987 Constitution provides our version of Due Process Clause, particularly in the Art. III - Bill of Rights, Sec. 1 which provides that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws. Liberty in the Due Process includes the right to exist and the right to be free from arbitrary personal restraint or servitude. It includes the right of the citizen to use faculties in all lawful ways. (Albano citing Rubi v. Provincial Board of Mindoro. 39 Phil. 660). Moreover, the Article XV sec. 3 par. 1 of the Constitution provides that the State shall defend the right of spouses to found a family in accordance with their religious convictions and the demands of responsible parenthood. Since our Constitution provides zones of privacy, akin to what the U.S. Constitution supports, we can say that we also uphold the right to marital privacy. And having the right to marital privacy, our Constitution rejects the purpose of the Connecticut laws in prohibiting and penalizing persons who use contraceptives and as well as those who are accessory to it, as what the U.S. Supreme

Court has demonstrated, that is to say, the repulsive notion of searching the marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives. We also have our Due Process clause in the Constitution which provides the concept of liberty. Following the argument of Justice White, the telling effect of the Connecticut statute on the freedoms of married persons deprives such persons of liberty without due process of law. Further, the assailed Connecticut law, which bans the use of contraceptives even for family planning, cannot support the right of the spouses to found a family in accordance with their religious convictions and the demands of responsible parenthood as found in Sec. 3 par. 1 Art. XV of the 1987 Constitution. Sec. 53-32 and 54-196 of the General Statutes of Connecticut do not conform to our 1987 Constitution, and thus, must be struck down as unconstitutional. AFFIRM THE RULING OF GRISWOLD V. CONNECTICUT, 381 U.S. 479.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Ust Pathology Report 9 2020Documento1 paginaUst Pathology Report 9 2020Mariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal LAW: I. Revised Penal Code - Book IDocumento2 pagineCriminal LAW: I. Revised Penal Code - Book IRS SuyosaNessuna valutazione finora

- SettlementAgreementForm FAA DisputesDocumento3 pagineSettlementAgreementForm FAA DisputesJayhze DizonNessuna valutazione finora

- AccentDocumento12 pagineAccentMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus For Bar Exam 2019 - Labor LawDocumento3 pagineSyllabus For Bar Exam 2019 - Labor LawVebsie De la CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus - Bar Exam 2019 - CIVIL-LAWDocumento4 pagineSyllabus - Bar Exam 2019 - CIVIL-LAWVebsie De la CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- EIKEN Advice For ALTs and StudentsDocumento12 pagineEIKEN Advice For ALTs and StudentsMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal AND Judicial Ethics AND Practical ExercisesDocumento2 pagineLegal AND Judicial Ethics AND Practical ExercisesMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mercantile Law: I. Letters Ofcredit and Trust ReceiptsDocumento4 pagineMercantile Law: I. Letters Ofcredit and Trust ReceiptsMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Taxation LawDocumento4 pagineTaxation LawMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic: State Authority To Punish CrimeDocumento8 pagineTopic: State Authority To Punish CrimeMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jirah Rapha Company and Mr. Roderick Iglesia Y TuralloDocumento1 paginaJirah Rapha Company and Mr. Roderick Iglesia Y TuralloMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic: State Authority To Punish CrimeDocumento8 pagineTopic: State Authority To Punish CrimeMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wedding 900 Per Head 2018 (Exclusive)Documento4 pagineWedding 900 Per Head 2018 (Exclusive)Mariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Deed of AssignmentDocumento2 pagineDeed of AssignmentMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pangalan Tungkulin Mon Tue Wed Fri SatDocumento2 paginePangalan Tungkulin Mon Tue Wed Fri SatMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Australia 2019: 10 Daisy Street Croydon Park, New South Wales 2138, AustraliaDocumento2 pagineAustralia 2019: 10 Daisy Street Croydon Park, New South Wales 2138, AustraliaMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quotation For A Five Kilowatt Solar Grid Tied System: October 15, 2015Documento4 pagineQuotation For A Five Kilowatt Solar Grid Tied System: October 15, 2015Mariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mariamb L00004491296Documento2 pagineMariamb L00004491296Mariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- DosDocumento1 paginaDosMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Day 1 - Sat 14-Oct Time Place To Do CostDocumento2 pagineDay 1 - Sat 14-Oct Time Place To Do CostMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Powers of Administrative Agencies: Tests of Delegation (Applies To The Power To Promulgate Administrative Regulations)Documento28 paginePowers of Administrative Agencies: Tests of Delegation (Applies To The Power To Promulgate Administrative Regulations)Mariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Waiver of Bank Secrecy Law SampleDocumento3 pagineWaiver of Bank Secrecy Law SampleMariam Bautista50% (2)

- Real Property Taxation ReportDocumento35 pagineReal Property Taxation ReportMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bio Research Dr. A Santos Ave. Sucat Paranaque CityDocumento2 pagineBio Research Dr. A Santos Ave. Sucat Paranaque CityMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sworn Declaration: Annex DDocumento1 paginaSworn Declaration: Annex DMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Relations Between Husband and WifeDocumento23 pagineRelations Between Husband and WifeMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Annex DDocumento2 pagineAnnex DPatrick DazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shape UpDocumento1 paginaShape UpMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter of Authorization-CamilleDocumento1 paginaLetter of Authorization-CamilleMariam BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Decree Law 45 of 2021Documento11 pagineDecree Law 45 of 2021aleefaNessuna valutazione finora

- Colegio Vs MerisDocumento2 pagineColegio Vs MerisMaggieNessuna valutazione finora

- A.K. Jain Constitution 2nd Part PDFDocumento353 pagineA.K. Jain Constitution 2nd Part PDFPragalbh Bhardwaj100% (1)

- History of Arbitration Practice and LawDocumento11 pagineHistory of Arbitration Practice and LawMay RMNessuna valutazione finora

- Guevara Vs GuevaraDocumento2 pagineGuevara Vs GuevaraClaudine SumalinogNessuna valutazione finora

- North Sea Continental Shelf CasesDocumento110 pagineNorth Sea Continental Shelf CasesSam SaripNessuna valutazione finora

- Care Credit AppDocumento7 pagineCare Credit AppwvhvetNessuna valutazione finora

- Indiana Life Cliff Notes NEWDocumento35 pagineIndiana Life Cliff Notes NEWDenise CampbellNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 Imperial V CADocumento1 pagina05 Imperial V CAFrances Lipnica PabilaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Legaspi V. City of CebuDocumento1 paginaLegaspi V. City of CebuNico RavilasNessuna valutazione finora

- Chain Swivel Shackle Standards BS en 14606-2004 - (2017-03-20 - 11-58-13 Am) PDFDocumento28 pagineChain Swivel Shackle Standards BS en 14606-2004 - (2017-03-20 - 11-58-13 Am) PDFNaw Az100% (1)

- UntitledDocumento14 pagineUntitledoutdash2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Graphic Designer First Amendment OpinionDocumento70 pagineSupreme Court Graphic Designer First Amendment OpinionZerohedgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Relevant Facts: Re: Definition of GamblingDocumento3 pagineRelevant Facts: Re: Definition of GamblingMaria AnalynNessuna valutazione finora

- Advan Motor V VeneracionDocumento7 pagineAdvan Motor V Veneracion'Naif Sampaco PimpingNessuna valutazione finora

- Insurance Law ReviewerDocumento35 pagineInsurance Law Reviewerisraeljamora100% (4)

- Employment Agreement 1Documento5 pagineEmployment Agreement 1Saad JawedNessuna valutazione finora

- 160 Pamatong Vs ComelecDocumento2 pagine160 Pamatong Vs ComelecJulius Geoffrey TangonanNessuna valutazione finora

- Invasion of PrivacyDocumento2 pagineInvasion of PrivacyJan Jamison ZuluetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Air and Space LawDocumento52 pagineAir and Space LawBharath SimhaReddyNaidu100% (1)

- UCSD vs. USC, Paul Aisen, Et Al.Documento87 pagineUCSD vs. USC, Paul Aisen, Et Al.Greg HuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Jai-Alai Corp. of The Phils. v. BPI (1975)Documento3 pagineJai-Alai Corp. of The Phils. v. BPI (1975)xxxaaxxxNessuna valutazione finora

- 88 - People Vs SenerisDocumento8 pagine88 - People Vs SenerisAnonymous CWcXthhZgxNessuna valutazione finora

- Oblicon CasesDocumento231 pagineOblicon CasesJessa MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Main - Recording Contract TemplateuDocumento5 pagineMain - Recording Contract TemplateuRap MonsterNessuna valutazione finora

- 4-9 (Formilleza Up To Deloso)Documento4 pagine4-9 (Formilleza Up To Deloso)nchlrysNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospective Overruling-An Indian PerspectiveDocumento7 pagineProspective Overruling-An Indian Perspectivead_coelumNessuna valutazione finora

- Plumbing MathematicsDocumento24 paginePlumbing MathematicsbenNessuna valutazione finora

- EH403 Corporation Code Reviewer - Title IDocumento19 pagineEH403 Corporation Code Reviewer - Title IKaiser100% (3)

- Role of ArchitectDocumento31 pagineRole of ArchitectVyjayanthi Konduri100% (2)