Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

SEZ

Caricato da

MohanChand PandeyCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

SEZ

Caricato da

MohanChand PandeyCopyright:

Formati disponibili

What Are Special Economic Zones?

By Megan Murray February 9, 2010

I. Introduction

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are defined as geographical areas, governed by one oversight management body, that offer special trade incentives to firms who choose to physically locate within them. Many countries employ their own variations of these special enclaves, and in doing so use their own terminology to describe them. For example, Mexico refers to its zones as maquiladoras, Ghana, Cameroon, and Jordan have industrial free zones, the Philippines calls its economic zones special export processing zones, and Russia has free economic zones. Despite the differences in nomenclature, each SEZ operates to increase trade throughout its respective region by offering special trade incentives to stimulate local and foreign investment within the region. The first modern special economic zone was created in Puerto Rico in 1942. Since then, 135 countries, many of them emerging markets, have developed over 3,000 zones. Their development has helped to improve global trade relations and has created over 70 million jobs and hundreds of billions of dollars in trade revenue. Special Economic Zones are generally implemented to meet fiscal, social, and infrastructure policy rationales. The most important fiscal goal of an SEZ is to facilitate economic growth through the use of reduced tariffs and more efficient customs controls. They are also essential tools for companies seeking to cut costs and improve inventory efficiency, and they help developing nations rework poor, inefficient trade policies and dilapidated or non-existent infrastructure. Part II of this Briefing Paper describes the different types of SEZs available to host countries, Part III and IV discuss the physical and regulatory characteristics of these zones, Part V describes the different incentives associated with SEZs, Part VI addresses the public and private nature of SEZ development and oversight, and Parts VII and VIII review the advantages and disadvantages of using an SEZ as a trade tool.

II. Different Kinds of Special Economic Zones

Special Economic Zones are generally classified as zones that promote increased, streamlined trade through beneficial taxation schemes and reduced customs oversight, but many nuances have developed within this broad framework to accommodate specialized industries, working conditions, country infrastructure, government oversight, and geographies.

A. Free Trade Zone

One of the most expansive types of SEZ is a Free Trade Zone (FTZ). An FTZ is a geographically fenced-in, tax-free area that provides warehousing, storage, distribution facilities for trade, shipping, and import/export operations in a reduced regulatory environment, meaning they generally have less stringent customs controls and sometimes fewer labor and environmental controls. These zones generally focus on the tangible operations of international trade. Because many SEZs attract laborintensive manufacturing such as assembly-oriented production of apparel, textiles, and electrical goods, FTZs like the Colon Free Zone in Panama are a very popular type of SEZ.

B. Export Processing Zone

Another type of SEZ is an Export Processing Zone (EPZ). These zones are similar to FTZs in that they encompass large land estates that focus on foreign exports, but they differ in that they do not

provide the same degree of tax benefits or regulatory leniency. They instead provide a functional advantage to investors seeking to capitalize on the economies of scale that a geographic concentration of production and manufacturing can bring to a trade region. These zones are beneficial to a host country, if they are successful, because the host country does not have to provide reduced tariffs or regulations but it still benefits from increased trade to the region. Hybrid EPZs are also geographically delimited zones, but they are broken down into specialized zones that cater to specific industries. In a hybrid EPZ, all industries use the general zones central resources, but each industry also operates within its own zone created to streamline specialized processes unique to those industries. An example is the Lat Krabang Industrial Estate in Thailand where all investors have access to the general trade area, but within it is a specialized, exportprocessing zone that only certain export-based investors may utilize. Sometimes these specialized areas are actually fenced off, while other times they are fully integrated within the general SEZ area.

C. Enterprise Zones

Enterprise Zones not only provide manufacturing or production benefits like other SEZs, but they also provide unique benefits of local, centralized development efforts. They are generally created by national or local governments to revitalize or gentrify a distressed urban area. The Empowerment Zone in Chicago is an example of an Enterprise Zone. It was created to revitalize certain south and west Chicago neighborhoods and bring trade to the area by increasing public safety, providing better job training, creating affordable housing, and fostering cultural diversity. If a specific industry is well suited for growth in an enterprise zone, it may take on characteristics of an EPZ or a hybrid EPZ, but the Zones purpose in promoting trade is secondary to its goal of gentrification and revival. These zones use greater economic incentives than EPZslike tax incentives and financial assistanceto revitalize the area by bringing trades into the zone that will spur organic, localized development and improve local inhabitants quality of life. This organic growth model assumes that improvement of a regions industry and trade begins at the individual neighborhood level.

D. Single Factories

Single Factories are special types of SEZs that are not geographically delineated, meaning they dont have to locate within a designated zone to receive trade incentives. They instead focus on the development of a particular type of factory or enterprise, regardless of location. A host countrys goal in utilizing a single factory model is to create specialization in a specific industry. A country that desires to create an export concentration in a specific industry would use a single factory model to promote trade and growth in just that industry, giving each factory specializing in that trade economic incentives. One of the most notable single factory examples is the maquiladora in Mexico. Here, factories specialize in the importation of foreign merchandise on a temporary basis where workers assemble or manufacture specific goods and then ship them out to other nations.

E. Freeports

Some zones specialize more in human capital goods and services such as call centers and telecommunication processing rather than manufacturing-based industries. Freeports are typically very expansive zones that encompass many different goods and service-related trade activities like travel, tourism, and retail sales. The variation of products and services available to a Freeport cause them to be more integrated with the host countrys economy. Most encourage a fully integrated life on-site for those who work in the Freeport, as opposed to just using the SEZ for manufacturing, production and shipping. Examples of these zones can be found in India and the Philippines where large military bases have been converted into Freeports that now function as specialized cities.

Koreas International City on the island of Cheju is another example of a Freeport in use. People live and work on the island and use the Freeport as a draw for high technology, tourism, and financial products industries.

F. Specialized Zones

In addition to Enterprise Zones and Freeports, Specialized Zones have been established to promote highly technical products and services unique to an industry. Many of these zones focus on the production and promotion of science and technology parks, petrochemical zones, highly technical logistics and warehousing sites, and airport-based economies. For example, Dubai Internet City is a specialized zone that focuses solely on the development of software and internet-based services. The Labuan Offshore Financial Centre in Malaysia is another example of a specialized zone that caters mostly to the development of off-shore financial services.

III. Characteristics of Successful SEZs

Despite the vast number of SEZs across the globe, the majority of SEZs are concentrated in just a few countries. China has been the most successful in implementing SEZs, and the most profitable in their operation. Most of Chinas SEZs are very large and specialize in a narrow range of products and servicesthose most conducive to a mass-production environment; notably labor intensive, assembly-oriented products. Chinas Shenzhen Village is very well known for transforming a small fishing village into a booming urban metropolitan area home to an export-oriented economy that brings in over $30 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) annually. The most successful SEZs not only specialize in a specific product or industry, but are also located within close proximity to transportation outlets and supported by dense and efficient infrastructure. For example, manufacturers using highly developed SEZs that can provide goods and services to the global stream of commerce quickly by using developed roadways and transportation systems will probably fare better than manufacturers using SEZs with undeveloped infrastructure and poor access to global commerce. The SEZs that must build the infrastructure in addition to the SEZ unit development also incur additional costs that reduce the overall profitability of the SEZ for the host country. Additionally, SEZs that have incorporated life communities within their SEZs have better access to employees than SEZs where employees must commute great distances to and from the developments. The development of service industries located either inside an SEZ or very nearby also helps to increase the profitability and economic efficiency of the corporations doing business within the zone. Global industrialization has helped to develop entire cities like Shenzhen Village whose sole purpose and infrastructure was the result of special economic zones. Some of these cities have been able to break free of their initial SEZ classification and develop into modern, investment hubs, like Taiwan, whereas others like Ho Chi Minh City remain notable only for their low-skilled textile and apparel manufacturing industries.

IV. Regulatory Characteristics of SEZs

The regulatory procedures of SEZs have changed since their original inception. For example, government regulation of SEZs originally mandated that most zones be located in remote locations or clearly delineated with fences or physical boundaries. Difficulties in attracting businesses to isolated areas prompted host country governments to establish more flexible boundary regulations that treated SEZs more like large scale, inter-city property developments rather than isolated trade zones. Original zones were also mostly restricted to export-based industries, whereas newer regulations allow SEZs to emphasize both imports and exports.

Some of the incentives now offered by many SEZ programs include provisions for commercial and professional activities, allow zone developers to supply utilities to the zone, allow for private instead of public development, and relax minimum export requirements and labor and environmental laws. In contrast, older regulations only provided incentives for government-developed SEZs that focused on traditional manufacturing activities. Even though the benefits of these more lenient regulations have helped to draw global corporations looking for cost-effective ways to grow businesses and improve a host countrys total foreign trade revenue, they sometimes come at the expense of government control and oversight over economic development. For example, once private development of SEZs was allowed, host governments lost a certain amount of day-to-day control over SEZ operations. SEZ approval processes have also changed over time. Many SEZs were originally approved by a single government board using an arduous approval process that cost a great deal of time and money. The burdensome process frustrated investors and often thwarted plans to bring new business to the host country. Today, many SEZs are approved by a more streamlined registration process in which applications meeting specified criteria are generally approved systematically. Indias recent regulatory reforms provide an example of the changes that some countries have adopted to streamline SEZ regulation. In 2000, India introduced formal regulations for SEZ development within the country to overcome the originally unclear, politically based procedures for SEZ implementation. However, these new regulations were still too cumbersome and confusing for foreign investors to follow, so in 2005, India reformed its SEZ regulations in a new SEZ Act of India that provided for quicker approvals and more transparent management of SEZs to promote exports and FDI in India. The new Act provides a regulatory environment that governs standards like SEZ size, development and oversight. Once the proposed SEZ meets the Acts criteria of proper proposal submission, financial requirements, and certification of sufficient utility access, an SEZ can be set up anywhere in the country. Like other aspects of special zones, each zone has its own unique regulatory body. Some zones, like the Philippines, use one governing board like the Philippine Economic Zone Authority to oversee all activities within the zone. Other zones use multiple bodies to oversee unique aspects of regulation, planning, and promotion of SEZs like Indias three-tier administration consisting of a Board of Approval, a Unit Approval Committee, and a Zone Development Commissioner to oversee the SEZ Act and ensure its proper implementation. There are advantages and disadvantages to both systems. Single governing boards overseeing every aspect of an SEZ have ultimate authority, as there is no other body to endorse its decisions. These circumstances provide no other authority check or idea generation. On the other hand, governing bodies with multiple boards can help balance control and decisions, but can run into differing points of views and conflicts of interest that slow down or totally obstruct an SEZ proposal, or frustrate successful SEZ operations.

V. SEZ Incentives

The purpose of an SEZ is to provide global corporations with an incentive to invest in the development and infrastructure of a foreign country through the use of a tax-friendly environment. Reducing a companys income taxes will have a direct positive benefit on earnings, allowing the investing company to profit from its foreign investment within the SEZ. Most of the benefits that investors look for in an SEZ are economic benefits such as tax holidays, reduced tax-rates, and duty-free imports. Some of these benefits are permanent and last as long as the investor does business in the SEZ, but other economic benefits are reduced over time. For instance, Indias new SEZ Act allows for a corporate income tax holiday that is gradually reduced from 100% tax abatement to 0% over 15 years, but Namibia has promoted its SEZ using a 100%, 99-year tax abatement. Not all benefits are financial, however. Procedural benefits like quicker customs processing and reduced regulatory requirements on labor and environmental policies also lure corporations to SEZs.

The SEZs host country government also benefits when a corporation chooses to locate within its SEZ location. To the extent that taxes are not completely abated, a host country earns income tax revenue from the corporate earnings within the country. It also earns income from import duties if not totally abated and charges on zone output levels. Depending on who actually oversees the SEZ the government or a private entity, or boththe operator also earns fees on land and facility leases within the zone. In-zone benefits are not the only benefits derived from investment in an SEZ. The improved infrastructure and quality of life that result from successful SEZs improve the surrounding regions economy. For example, the Shenzhens growth from a sleepy fishing village to an economic powerhouse has provided its citizens with more opportunities for employment and better access to services than the fishing village was able to provide before the establishment of the SEZ. These SEZ benefits do not come without costs, however. The host government or private operator of the zone usually incurs its own costs of oversight and administration of the zone. Costs of ensuring that those outside the zone do not use the SEZs economic or regulatory benefits is also a high cost of oversight for any SEZ. The developer of the SEZ also has the enormous task and cost of developing the infrastructure needed to attract foreign investors, because insufficient means of transporting SEZ-processed goods to their destinations dilutes the SEZs overall economic benefits. Often, the high costs of infrastructure development are absorbed by a host government desperate to attract foreign investment. The government might subsidize the cost of development in order to lure a developer into the region. Therefore, before a host country approves an SEZ development, it must weigh the benefits that an SEZ might bring to the country in trade revenues against the total costs of SEZ implementation, including the cost of construction and long-term operation.

VI. Private/Public Nature of SEZs

Initially, SEZs were government-sponsored projects intended to promote foreign investment that would only benefit the country at the governmental level. In the 1980s, the first privately-developed SEZs were created in the Caribbean and Central America to compete with government trade zones that were often fraught with inefficiencies and cumbersome regulations. By the end of the 1980s, approximately 25 percent of all SEZs were privately run. More recently, about 62 percent of SEZs are run by private developers seeking to capitalize on the enormous economic benefits of foreign trade and investment. These new private zones created their own problems, however, because they were largely unregulated and their rapid growth strained infrastructure, facilities, and services. In the Dominican Republic, sudden and unexpected growth of privately-developed SEZs wreaked havoc on local infrastructure and prompted bans on new SEZ development. Modern private SEZs in the country are required to locate close to existing infrastructure and facilities to reduce excessive government outlays. Despite initial problems, the privatization of SEZs has been beneficial to their global acceptance and economic effectiveness. Private developers have used their vast resources to create higher-end SEZs than many host countries could create with their governmental budgetary restrictions and operational constraints. Private developers can also command higher rental rates because many investors prefer to locate in efficiently configured, privately-run zones that have better social and environmental facilities than those of their public counterparts, which are often crowded, poorly designed, and have inadequately maintained facilities. For example, rental rates in the privately-run zones of the Dominican Republic are as much as three times the rental rates of the publically-run zones in the country, a phenomenon largely attributed to the superior quality of the private facilities. The fact that government-run SEZs are often cost-inefficient does not necessarily mean that government involvement is completely unnecessary. Public-private partnerships have become increasingly important in SEZ implementation because such a joint enterprise provides the best attributes of both parties. Private investors bring coveted development expertise, contracts for private management and leasing, and financing, while host country governments bring public funds

for infrastructure development (roads, utilities, etc.), local country expertise, and additional financial support. Local governments also aid in assembling the large land acreages needed to create a geographically-based SEZ. For example, the Pomeranian Special Economic Zone is a unique SEZ development in Poland that has been created using an assemblage of public land and existing infrastructure along with new private construction by global investors. This kind of public-private partnership helps reduce costs for both parties and improves the economic returns of the SEZ. Both parties benefit from the initial resources each provides to the development, and also from the others long-term involvement in SEZ. The developer earns the right to market and use the SEZs tax incentives and regulatory benefits to grow its investment, while the government attracts international businesses that provide FDI revenue and investing expertise to the host country.

VII. SEZ Challenges

The development of SEZs has not come without significant costs. One of the reasons for investor success in some SEZs is that they avoid many of the costs of taxation, labor standards, human rights oversight, safety, and environmental regulations to which other sectors in the same country must adhere when doing business. Some academics argue that these regulatory-avoidance mechanisms ultimately benefit the citizens because SEZs bring employment and infrastructure to the area, while opponents argue that the zones benefits are not worth the degradation that the SEZs cause to a developing country. For example, displacement challenges have a very significant impact on any SEZ implementation. Initially, the host country or private developer must acquire the land area used to implement a geographically-based zone. Most of the time this land is taken from locals using it for agricultural purposes, often at very low prices, like when Indias local Tamil Nadu government cut the price of the farmers land in half to accommodate the Nokia Telecom SEZ development in Sriperumbadur, Kancheepuram. Aside from the low prices farmers obtain for their land, the problem with the acquisition of farmland for SEZ development in developing countries is two-fold: First, farmers in these environments might make a living through subsistence farming, in which case the land that is acquired is the farmers sole means of food and livelihood. Second, even if farmers farm for profit, some have very low-level skills that are not transferrable to more complex SEZ unit employment like manufacturing or technology-based trades. The acquisition of their land displaces them from their economic means of survival and forces them into an unfamiliar environment where they lack the skills to stay and work in the SEZ unit. If they also lack the resources to move, they are left without a farm or survival skills. The challenges associated with the development of SEZs do not end when an SEZ is fully developed. SEZs also create environmental concerns because host governments often relax environmental standards to attract SEZs or overlook them because of the high costs of regulation and oversight. Emission controls and labor standards are regulations that an SEZ developer will try to avoid because they cut into SEZ profitability. But environmental controls and oversight are especially important because SEZ development can lead to quick growth and outpaced infrastructure that leads to waste and environmental devastation. Shenzhen in China, a highlypolluted trade area where the sky is gray most of the day from the polluting industries, is a perfect example of the environmental impacts that rapid SEZ growth can have on an area. In certain areas within an SEZ in Mumbai, the creeks are so polluted that no one can fish. Many attribute the pollution there to the fact that no environmental laws apply to the SEZs. In Tijuana, Mexico, the Rio Grande is so polluted from maquiladora waste that it has caused an increased risk of Hepatitis A. Another obstacle that SEZs face is the high cost of development. Governments that lure developers

by providing infrastructure capital and tax subsidies must ensure that they recover their costs in doing so. Some SEZ developments have cost the host country more to build than they bring in trade revenues, negating the benefits the trade region brings to the country. Some academics have referred to this practice as a race to the bottom. For example, Namibia offered greater economic and regulatory concessions to foreign investors than its neighboring countries of South Africa and Madagascarin the form of 99-year tax exemptions, water and electricity subsidies, and relaxed labor standardsas a way to compete for SEZ investors. While Namibia eventually won the contract, it did not result in an overall social or economic net benefit to the country. This kind of strategy produced a downward spiral in SEZ conditions across the continent as South African countries competed with each other by promoting reduced regulation and increased economic incentives. As a result, foreign investors reaped all the benefits of the competition while the host countries absorbed all the costs. Indirect costs of SEZ development should also not be overlooked. New and economically profitable SEZ areas can still cause social problems if they develop at the expense of the surrounding nonSEZ areas. An SEZ development can socially cannibalize its surroundings, diverting valuable resources into the SEZ that those living on the outside depend on to survive. These resources can be as simple as grocery stores and medical facilities and as complicated as high-tech jobs. The bottom line is that the creation of an SEZ development to better one sector of a countrys economy at the expense of another will widen the gap between the more prosperous living within SEZ areas and the poor living outside the SEZ, hindering the true net gain of the development. Poor labor standards are also a prevalent problem in SEZ developments. The alluring volume of international trade traffic, combined with the other relaxed custom, taxation, and environmental standards, leads many zones to overlook proper labor requirements that keep employees safe, healthy, and competitive. High traffic trade zones are most cost-effective when they employ lowskilled, low cost assembly-line workers. Historically, many of these employees have been paid extremely low wages to do repetitive skills in pollution-filled environments. Host country governments also have been known to suppress unions and workers rights groups to prevent employees from demanding better conditions. Not surprisingly, some of the most successful SEZs in China were actually totally exempt from national labor laws when they were first created in the 1980s. Zimbabwe and Namibia also excluded provisions of their nations labor acts when they initiated national EPZ laws in the early 1990s, drawing immediate criticism from the global human rights community. Namibia claimed that the avoidance of labor standards was absolutely necessary in drawing much needed foreign investment into the economically depressed country. Maquiladoras in Mexico are also very well known for their abhorrent labor conditions, including poor working environments, inadequate training, use of hazardous materials, and lack of knowledge about protective equipment. Gender inequality and the exploitation of female workers is another unfortunate product of SEZ development. Females originally accounted for 6070% of the SEZ workforce because many companies regard women as better suited for the repetitive textile- and electronic-based manufacturing industries that made up much of the initial SEZ work, but that percentage tends to decrease as product complexity increases. In Malaysia, for example, where technology is a large part of SEZ industries, currently 40% of the workers are women, down from 60% twenty years ago when its SEZs generally catered to simpler manufacturing based industries. Women are often separated from the male employees, used as lower-skilled workers to reduce production costs, and given fewer rights than their male counterparts. Fortunately, the labor standards in some countries are improving slowly as a result of their adoption of International Labor Organization standards. These standards are critical to prevent abuses, and foreign investors have been increasingly mandating quality labor management practices as a prerequisite to doing business with a host country.

VIII. SEZ Benefits

Even though SEZ developments bring challenges to host countries, they also bring valuable benefits. As already noted, an SEZs tax benefits help expand a countrys industrial base by luring foreign industries that might not otherwise choose to locate in the host country. Foreign direct investors doing business in a host country also improve host country facilities because one of the ways they compete for global business is through sophisticated, high-tech developments and worldclass facilities. These highly developed enclaves help offset country risks that many foreign investors consider when they consider investments in foreign markets. The new Songdo City in Seoul, South Korea, part of the new Incheon Free Economic Zone, is the epitome of a world-class SEZ. When completed in 2015, it will be a digital city that highlights all of the newest global technologies. SEZs also improve industries focusing on enhanced technologies by providing research and development resources that allow countries to export more sophisticated manufactured goods. Within these technologically sophisticated developments, large foreign firms often partner with smaller local firms, providing brand-name recognition and large firm expertise that gives the local firm greater global marketing visibility. Other economic benefits of the zones include increased government income from trade revenues once government subsidies expire, export growth and foreign exchange earnings, and lease revenues from firms renting space within the zone. Centralization of local and foreign trade facilities also helps stabilize employment levels and promotes ingenuity and experimentation of new trade regimes under a common infrastructure. A country can experiment with using different oversight methodologies and then calculate which regulations best meet its trade needs. Foreign direct investment promotes organic growth from within the country as locals develop new skill bases and improve their infrastructure, allowing them to compete at a higher level for subsequent foreign investments. SEZs help expand a host countrys employment base by creating additional jobs and training opportunities for more local citizens, and sometimes by actually improving a countrys labor standards. For example, employment in the Dominican Republics SEZs rose from 500 in 1970 to over 200,000 today, and almost 1 million workers are employed in the Philippines SEZs. And unlike Namibia, Mozambique has mandated that national labor laws apply to its SEZs and has guaranteed acceptable working conditions with mandatory vacation, minimum wage laws, and maternity leave. SEZs also generate economic activity outside the zone due to increased infrastructure requirements and a need for support services to transfer goods to and from a zones geographic area. Once SEZs generate additional employment and services, there is an increased demand for social infrastructure like housing, education, health and transport communication, shopping, tourism, hospitality, packaging, banking, and insurance, all of which combine to grow employment and improve the quality of life in and around an SEZ development.

IX. Conclusion

There is not one best way to establish an effective and financially profitable SEZ. Many countries have developed their own unique trade units to capitalize on their own laws, customs, resources and trade practices. Some of these developments have been successful, like the Shenzhen Village SEZ in China. Others, like those in Namibia, have failed because they were not financially profitable, or because the social, environmental, or political costs impeded their overall success. These successful and unsuccessful SEZs should serve as models for host countries seeking to develop new SEZs. The complexities involved with the development and management of an SEZ require that a new host country thoroughly understand all of the risks and rewards before implementation. SEZs can provide great investment benefits by luring companies with tax incentives and new technologies, but some of

these benefits might now be outweighed by the economic, social, and environmental costs.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grade-5-Dividing-Whole-Numbers-By-10-100-1000 AnswersDocumento6 pagineGrade-5-Dividing-Whole-Numbers-By-10-100-1000 AnswersMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

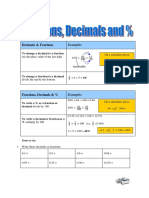

- Fractions and Decimals Questions and AwnsersDocumento20 pagineFractions and Decimals Questions and AwnsersMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Decimals Convert Fraction To Decimals QuestionsDocumento6 pagineDecimals Convert Fraction To Decimals QuestionsMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Decimals Convert Fraction To Decimals AnswersDocumento6 pagineDecimals Convert Fraction To Decimals AnswersMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Decimals, Fractions & Percentages Conversion GuideDocumento10 pagineDecimals, Fractions & Percentages Conversion GuideMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- IELTS1 Answer KeysDocumento23 pagineIELTS1 Answer Keysapi-384491577% (13)

- 3 Math 550 Decimals Worksheets 2Documento21 pagine3 Math 550 Decimals Worksheets 2Havoc Subash RajNessuna valutazione finora

- Class 6-8 Maths and Science QuestionsDocumento17 pagineClass 6-8 Maths and Science QuestionsRakesh SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher attendance record by subject and studentDocumento1 paginaTeacher attendance record by subject and studentMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Complete 7th STD Maths Test Paper For Maharashtra BroadDocumento21 pagineComplete 7th STD Maths Test Paper For Maharashtra BroadMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- 10th SSC Maharashtra Board Questiona PaperDocumento8 pagine10th SSC Maharashtra Board Questiona PaperMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- 10th SSC Maths Question PaperDocumento4 pagine10th SSC Maths Question PaperMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Model Paper 12th Sci Maths 2014Documento29 pagineModel Paper 12th Sci Maths 2014MohanChand Pandey100% (1)

- 5th STD NumbersDocumento2 pagine5th STD NumbersMohanChand PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Main Sulci & Fissures: Cerebral FissureDocumento17 pagineMain Sulci & Fissures: Cerebral FissureNagbhushan BmNessuna valutazione finora

- Final System DocumentationDocumento31 pagineFinal System DocumentationEunice AquinoNessuna valutazione finora

- COP Oil: For Epiroc Components We Combine Technology and Environmental SustainabilityDocumento4 pagineCOP Oil: For Epiroc Components We Combine Technology and Environmental SustainabilityDavid CarrilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban AmericaDocumento35 pagineSmell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban AmericaUniversity of Washington PressNessuna valutazione finora

- Senior Design Projects 201-2020 - For Website - MEDocumento5 pagineSenior Design Projects 201-2020 - For Website - MEYujbvhujgNessuna valutazione finora

- CalculationDocumento24 pagineCalculationhablet1100% (1)

- Calculating Molar MassDocumento5 pagineCalculating Molar MassTracy LingNessuna valutazione finora

- TM500 Design Overview (Complete ArchitectureDocumento3 pagineTM500 Design Overview (Complete ArchitectureppghoshinNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Power Dynamics and Developing Political ExpertiseDocumento29 pagineUnderstanding Power Dynamics and Developing Political Expertisealessiacon100% (1)

- 16SEE - Schedule of PapersDocumento36 pagine16SEE - Schedule of PapersPiyush Jain0% (1)

- 9.tools and Equipment 1Documento13 pagine9.tools and Equipment 1NKH Mega GasNessuna valutazione finora

- CROCI Focus Intellectual CapitalDocumento35 pagineCROCI Focus Intellectual CapitalcarminatNessuna valutazione finora

- Volvo S6 66 Manual TransmissionDocumento2 pagineVolvo S6 66 Manual TransmissionCarlosNessuna valutazione finora

- ERC12864-12 DemoCode 4wire SPI 2Documento18 pagineERC12864-12 DemoCode 4wire SPI 2DVTNessuna valutazione finora

- Radiograph Evaluation ChecklistDocumento2 pagineRadiograph Evaluation ChecklistZulfadli Haron100% (1)

- Maytag MDG78PN SpecificationsDocumento2 pagineMaytag MDG78PN Specificationsmairimsp2003Nessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head:: Describe The Uses of Waiting Line AnalysesDocumento6 pagineRunning Head:: Describe The Uses of Waiting Line AnalysesHenry AnubiNessuna valutazione finora

- Holacracy FinalDocumento24 pagineHolacracy FinalShakil Reddy BhimavarapuNessuna valutazione finora

- Designers' Guide To Eurocode 7 Geothechnical DesignDocumento213 pagineDesigners' Guide To Eurocode 7 Geothechnical DesignJoão Gamboias100% (9)

- Quiz 1Documento3 pagineQuiz 1JULIANNE BAYHONNessuna valutazione finora

- REFLEKSI KASUS PLASENTADocumento48 pagineREFLEKSI KASUS PLASENTAImelda AritonangNessuna valutazione finora

- MAPEH 6- WEEK 1 ActivitiesDocumento4 pagineMAPEH 6- WEEK 1 ActivitiesCatherine Renante100% (2)

- SEW Motor Brake BMGDocumento52 pagineSEW Motor Brake BMGPruthvi ModiNessuna valutazione finora

- 21st Century Literature Exam SpecsDocumento2 pagine21st Century Literature Exam SpecsRachel Anne Valois LptNessuna valutazione finora

- Exp-1. Evacuative Tube ConcentratorDocumento8 pagineExp-1. Evacuative Tube ConcentratorWaseem Nawaz MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- CLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveDocumento57 pagineCLOZE TEST Fully Revised For SSC, Bank Exams & Other CompetitiveSreenu Raju100% (2)

- Popular Mechanics 2010-06Documento171 paginePopular Mechanics 2010-06BookshebooksNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3.1 - Hydrostatic ForcesDocumento29 pagineUnit 3.1 - Hydrostatic ForcesIshmael MvunyiswaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brake System PDFDocumento9 pagineBrake System PDFdiego diaz100% (1)

- Advanced Scan I21no2Documento29 pagineAdvanced Scan I21no2Jaiber SosaNessuna valutazione finora