Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Desjarlais Review

Caricato da

Claude JousselinTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Desjarlais Review

Caricato da

Claude JousselinCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1

Robert Desjarlais

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Body & Emotion review Shelter blues review Counterplay review Overview and relevance to my research influence map

Body and Emotion or the ethnographer as diviner.

In this phenomenological study of the healing practices of the Yolmo people of Nepal, Desjarlais promotes the idea that body and spirit are conceived differently in different places; for the Yolmo, the body is like a dwelling that houses spiritual forces that becomes an empty shell when death occurs and of less importance than the spiritual world. In providing ethnographic details of the shamanic diagnosis of illnesses he demonstrates how aesthetic values are embodied and that illness experiences are imbues with the specific cultural context. The book is made of two parts; the first concentrates on the threats to health as experience by the Yolmo people, provides the cultural and historical context in which to explore the notions of personhood and describes the links between emotional distress, personal tensions and the diagnosis of soul loss Chapter 1 Desjarlais presents his approach to ethnography through exploring how other ethnographers explain their trance experience and questioning if we can really experience what other cultures do. The visions that come to him in trance do not provide the same opportunity for divining the causes of illnesses as it does to the shaman, not only because he is an apprentice but also because he is an outsider to the culture; as he is told he does not know the language enough nor does he know what the god looks like. Nevertheless, if these visions were not helpful to the Yolmo people he experienced their divinatory power in relation to his fieldwork and ethnographic inquiry. To some extent this could be compared to a kind of self-analysis, Jung being directly mentioned in relation to dream interpretation, but its value for understanding another culture is problematic. Desjarlais in referring to Batesons self system claims that the anthropologist can access unconscious or tacit knowledge through dreams and divination, and that it is important to be open to information that may come from different sources, externally as well as internally. But there are limitations to this stance as the visions rather than being revelatory may have been reinterpreted posteriorly and more a representation of Desjarlais concerns that the Yolmos world. Devereux reminds us of the double edged self-model that both facilitates and hinders the understanding of others by considering ones own experience of the world as prototype for the rest of the world. With this caveat in mind, Desjarlais insight is important as he describes these

2 transcendent experiences not in terms of their psychic content but as direct links with the everyday lives and concerns of the shamans patients. . He describes how the body moves in a particular way when a person is in trance, and explains that his awkward shaking that is so different to the shamans, is partly due to being an apprentice, but also to the specific way his body interact with the world , which is peculiar to him an his cultural background. He uses the example of the crouching position, with feet flat on the ground, elbows tucked in and head held low, familiar to the Yolmo men and uncomfortable to him, which as he practices it gives him an embodied insight to the physical experience of shaking involved in trance. In turn this knowing through the body also gives him an understanding of how the Yolmo people experience and organise their daily activities. Through these examples he emphasises a move away from an interpretive and intellectual approach to learning and understanding another culture through acquiring an embodied knowledge as well as through imaginative work, dreams and trance. This was in part a strategy to adapt to the close and private ways of the Yolmo when it comes to sharing their thoughts and views, which made interviews, life histories an impossibility, as well as a method adjusted to the Yolmo people that describe their dreams through images, snapshots, rather than through a constructed narrative. Chapter 2 In this chapter, Desjarlais develops his argument that the physiology of an experience is intertwined with its cultural aspects and that both influence each other. He explains that according to the Yolma people the body is represented as a house, and that it protects the soul from the outside, and suggests that this image of the body is a microcosm of the way the world of the Yolmo is organised. Thus the same tension between autonomy and interdependence is find at different levels; corporally, as the body is always experienced in relation to others; in the households that share resources yet compete for status; in the villages that attempt to create unity in opposition to outsiders. Overshadowing this ambivalent feeling towards togetherness is a fear of fission and fragmentation which may affect overall harmony of the Yolmo people, including of their body, which would allow for the intrusion of spirits and hosts and causing illness. Nevertheless the authors claim to describe a unique grammar of experience of the Yolmo people was not entirely convincing as some of his descriptions seem familiar to western concepts, such as the body described as a bounded shell that protects and separate self from environment or that social conflicts spark illness. Chapter 3 describes how an elderly man, Mingma Lama lost five of his nine life supports to ghosts, and demonstrate the causal links between the local sensitivities and ways of being, which Desjarlais calls the aesthetic of experience, and the development of illness such as soul loss. He suggests that the social and personal tensions already discussed are framed within values of harmony, purity and wholeness and that the repression of emotional distress causes illness. He argues that Mingmas experiences of soul loss as a fated aging process and expressed through images of walking alone at night, reflects the values of his society and can be best understood through the aesthetic of the way of life of the Yolmo, the artistry of human forms, rather than by interpreting symbols and texts.

3 Are the images mentioned different to the illness metaphors described by Sontag? The poetic images of the moon and of mute feet reflects the environment and society of the Yolmo just as Sontag argues the battlefield and warlike expressions are part of the western psyche in relation to illness. But does the metaphoric inversion she describes and abhors, whereby illness is used to describe other elements of society, exist in the Yolmo people? Desjarlais does not explore this, nor does he indicate how the changes in the Yolmo society triggered by the introduction of a market economy may alter the aesthetic of everyday experience and the images used to explain illnesses. In Chapter 4 , Desjarlais strategically distanced himself from the discursive investigation of emotions, where meaning takes precedence over practice, and examines a funerary song in terms of the experience it portrays as well as the language used to express these emotions. He argues convincingly that to ignore the possibility that what is said is also being felt would be to intellectualise all experiences and ignore the visceral experiences that we all have everyday. His analytical strategy is best demonstrated as he explores in details the different meaning within various contexts of the words tsher ka around which the song of pain revolves. Whilst dictionaries translate the word as sorrow, pain or grief, Desjarlais uses images provided by the Yolmo people to complicate and nuance it and highlights that it is mostly referring to the pain of separation and isolation, the main fear and tension in Yolmo society. Chapter 5 follows a similar strategy to explore what it is like for a Yolmo individual to experience soul loss and rather than compare and contrast this to western depression, Desjarlais provides us with example of felt experiences and the associated divinations internal to the Yolmo society, such as images of falling when crossing a stream that explains how the soul was loss. In continuation with the preceding chapters he resists the idea that the soul loss and its associated feelings of heaviness, loss of motivation, lack of appetite, are expressions of something else and used as coping strategies. Instead he argues that there are times when pain is simply pain, that in the case of the Yolmo, there is little to be gained from the sick role, and suggests that it is more productive for his inquiry to focus on the visceral presence of the distress in what he calls a somatic sensibility. It is an attempt to move away from the concept of somatisation, including of the suspicion that there may be in the individual an ulterior motive for the pain, albeit an unconscious one. I would suggest that this acceptance at face value of what an unwell person says is linked to the notion of empathy that Desjarlais uses throughout the book in reference to the Yolmo society and that it can be problematic; his own desire to gain understanding of his participants inner world may be a reminder that the ethnographers peculiar position may distort the understanding of the emotions observed into an acceptable or exotic version of the Other. Part two of the book, healing, uses extensive ethnographic accounts to present cases of illness and the shamanic attempts to cure them in a chronological way; the divination, the exorcism and the revitalisation. Chapter 6 examines the diagnostic process used by the shaman through different type of divination, feeling the pulse, reading the rice and rhythmic trances, and explains how the notions of good health include physical as well as spiritual elements which

4 need addressing in the healing performance. He analyses a divination revealed to the shaman by a deity which includes spatial evocation of pain, distress and kinship, and concludes that the shaman transforms [distress and] unnamed suffering into cultural language of sorrow and pain. Divination is an act of healing, that brings the opportunity for self knowledge that is usually repressed by the cultural system, and it is described by Desjarlais in similar terms as psychoanalytical therapy that aims to uncover and resolve the individuals internal conflicts. Thus divination is transformative at the level of individual illness but also in terms of social dynamics as it contributes to collective experience. Chapter 7 is concerned with the treatment phase that follows the divination in the shamanic performance, in this case an exorcism of the ghosts that have entered the body. Desjarlais main and continuing argument is that it is not the symbolic meaning of the ghosts or demons once exposed and interpreted that will on their own resolve the illness; instead it is the corporeal practice, the act of touching that will make possible the cleansing and expulsion of the pain. Despite opposing psychoanalytical and symbolic explanations with phenomenological ones, there are some resemblance and common ground that weakens the argument. The collective circuit of knowledge and the uncharted regions of experience seem to be just other names for the Jungian collective unconscious. In Chapter 8, now that the illness has been diagnosed and the ghosts spirits removed, the shaman has to revitalize the person suffering, and bring back the life supports that had been lost. This leads Desjarlais to discuss how healing may be successful through exploring the notions of efficacy developed first through intellectualist analysis which explain the cure as the result of a leap of faith in the part of the patient, and secondly through symbolic analysis with associate the work of healing with the re-ordering of the symbols and worldview of the patient. Desjarlais questions the causality direction of these explanations claiming that symbolic re-ordering does not transform illness into health but instead is the consequence of the healing rite. He goes on to argue that the physiological, sensory dimension is missing in these explanations and that any explanation of efficacy of healing must take in consideration what patient themselves accept as successful healing. It is through the senses and feelings that individuals will know themselves to be better and cured, and not the other way round, knowing to be cured and then feeling better. Finally in chapter 9, Desjarlais examine the limitations of the Yolmo healing rite in curing illnesses by exploring the interrelation between, procedure, process and outcome of the healing rite. In doing so he concludes that Yolmo healing alleviate the pain but does not always deal with the causes of the ailments fully and that repeated rites are often required; that the rites are at they most effective with illnesses that are caused by social conflicts as the healing restores the idealised notion of health through the Yolmo values of harmony, purity and wholeness. The recent economic and political changes are in Desjarlaiss view affecting negatively these values and the cultural fear of fragmentation and fission are expressed through an increase prevalence of soul loss. Desjarlaiss phenomenological stance is reflected in his concerns with existential rather than political concerns and therefore the role and position of the shaman within the Yolmo society as possible keeper of the established status quo that may be causing the social conflicts, particularly in relation of gender tensions, is not explored.

5 But he does successfully reminds the reader that things are lived before they are explained, that not everything is a symbol for something else, that some things just are and that not to investigate this is missing an important part of everyday life. The consequence of such stance is the central role played by narrative in a phenomenological attempt to describe what others have called the lifeworld. Desjarlais is specifically aiming to engage the reader at the level of the body and pass on some of the feelings he experienced in the Yolmo village and his inclination is towards a poetic style rather than fiction, but unfortunately this does not come across. Instead there are many theoretical interventions in different chapters that explicitly explain and analyse and very few daily lives descriptions; his apprenticeship as a shaman could have provided the means to provide a sense of daily routine and events. This was the challenge that Desjarlais has set himself , how to know what is someone elses heartmind, and how to pass on this in the written form; the afterwords section shows his full awareness of the difficulty of analysing and representing other realities and his attempt to do this by focusing on sensibilities, feelings and the way things are experienced makes this an important and enjoyable monograph.

Shelter blues where the author at home develop a critical phenomenology.

This is a very dense book, possibly so as a literary strategy, that combines details ethnographic studies of homelessness, architectural reflections on mental illness, and philosophical explorations on the nature of human experience. It is constructed without chapters, which adds to the sensation of density, with paragraphs that are headed by saying and phrases from Desjarlaiss participants. It is at times opaque in the way theoretical discussions are developed, at other times frustratingly slight in the short interventions by his participants and seem to neglect discussions on the demography of the shelter, in particular issues relating to gender and race. Yet the authors critical phenomenology, that combines the study of things as they are as well as why they are that way, is very successful in providing a humane exploration into the lives of homeless mentally ill people, that should resonates with all readers living in large cities and liable to come face to face with homelessness. At the centre of his argument is his claim that what is meant by experience is socially and historically constructed and should not be taken for granted as a universal concept. He uses the example of mentally ill homeless people to describe instances where life is not conceived in relation to experience. His examination of the word experience, as a black box usually accepted and unquestioned, leads him to conclude that the life of people in a shelter does not always comprise all the elements necessary to be considered experiential He contrasts experience which is transformative, temporally constructed through narrative, internal and reflexive, with struggling along as a way of beings for the people using the shelter who are (a)not moving forward, (b)not presenting coherent narratives and (c)whose internal life is constantly challenging the possibility of reflection.

6 (a)Desjarlais describes the repetitive routine which provides some sense of safety and despite the staff affirming the need to move on, creates some dependency and discourage the propensity for change and becoming something else. This wrangling between progress, recovery, change and repetition, routine, safety is an important insight in the tensions at play in the institutionalisation process that has still relevance in wider social arenas. (b)The narratives people use to talk of their lives are episodic, fragmented and linked to events rather than being progressively formed, more like Beckett than Proust, and so memories are prone to change with the particular occupation that people engage with. This is partly due to the moves between different hospital wards and the shelter as well as the influence of pharmaceutical. (c)Medication also affects the capacity for reflection due to their soporific affect and compounded by the internal noise and voices as well as the external commotions and busyness of the shelter. He describes the communication between staff and people in the shelter as driven by a therapeutic capitalism that aims to install behavioural change in order to integrate them in the reasonable society. The staffs work within a concept of becoming, striving for change, whilst the people using the shelter functions in terms getting, keeping and retaining. Desjarlais use of the concept of struggling along as distinct to the concept of experience seems to be denying the possibility for people of becoming, to move forward. He makes a point to explain that his observations warn us against a reductionist view of selfhood and agency and that multiple forms of these maybe the result of political context to which some people, such as homeless, are subjected to. This interpretation, whilst highlighting the social suffering that is clearly present gives an overall sense of his participants as constituted, mediated, stamped to use his own words, emphasising their passive role. The way of being that Desjarlais describes as struggling along can be contrasted with Corins concept of positive withdrawal that interprets similar ways of being, such as retreat from the world and seeking calmness, as strategies and stances towards the world in order to integrate their psychotic experiences. Both authors suggests that the therapeutic enterprise of the 90s denies the possibility of being in different ways from the expected, autonomous, active and efficient personhood, and is the result of cultural , political and economical values. Corins psychological orientated research is aiming at improving psychosocial interventions and focuses on meaning and coping strategies through discourse analysis, whilst Desjarlais aims for a phenomenological descriptions of the everyday lives in a shelter. Their differing methods, observations and interpretations are the results of different purpose for their research and enrich each other to provide a fuller picture of life as mentally ill homeless may experience it. Desjarlaiss approach is at its most effective when he brings to light the busy internal communication and imagination that people with psychosis may experience through hearing voices. He provides striking and humane examples of the difficulty that people have in communicating with others whilst having internal conversations as well as talking ragtimes, a form of overstretched metaphors that are only understood by the speaker. Desjarlaiss approach as an ethnographer is adapted to this complex communication environment as he encourages his peers to resist interacting with people only in an interpretive manner and analysing peoples words, and

7 encourage a listening presence that could be equated with a therapeutic acceptance. This is worth heeding, with a caveat as it could be argued that Desjarlaiss phenomenological approach does not consider what interpretations participants have themselves whilst putting forward its own. Another centre piece of Desjarlais book is the exploration of the architecture of the State Center building that house the shelter as well as a locked psychiatric ward amongst other things. From the self evident premise of his argument that space and culture interact and affect one another, he focuses his inquiry specifically on how architecture is related to public notions of madness in the first instance then embodies symbols of power. The author contrasts with great effect the modernist and brutalist style of the architect involved with the descriptions from the users of the building. The monumental scale meant to include topographical elements has exposed structures made of raw concrete and aims for balance with more intimate spaces to activate the imagination. The title of the chapter a crazy place to put crazy people sets clearly the concerns of the author as to the link between spatial structure and psychological well being and provides short narratives that place such architectural theories in terms of everyday life in and out of the building; the fears of the razor-sharp walls, the staircase that lead to nowhere, the tranquillity of the open areas and so on. This effective narrative strategy that portrays a sensual perception of the building is augmented by the concept of the sublime described by Kant as a moment when the imagination is overwhelmed by the vastness of an object. The disorientation experienced by people trying to enter the State Center or the impressions of descending into an underworld when climbing down the stairs are two examples of the overwhelming sensations described. The reference to the architect wish to make magnificent ruins provides Desjarlais an analytical bridge and analogy between the decay of an unfinished building and the perception of homeless people as seen by the rest of us; the direct encounter with homelessness leaves one overwhelmed and unable to comprehend the totality of what it is to be living in the streets. Through his focus on the physicality of the shelter and the building as whole, the nook and crannies, the light and shade, Desjarlais concludes that in contrast to Foucaults reading of the Panopticon as the modern disciplinary model based on confinement and visibility, there is a system of displacement and obscurity applied to homelessness. The consequence is that disciplinary power does no longer need to be productive but instead scarce and precious resources are selectively protected and illuminated such as the touristic centres of cities, living whole areas like housing estates in obscurity redundant like psychiatric rehabilitation wards. The exploration of the interaction between space and individual by interjecting philosophical musings with explanatory narratives as led the author to make a political point that denotes the incapacity of the politics to respond to the situation of homeless and is an example of the critical phenomenology approach that he advocates. It also highlights how structural inequalities have a direct impact on what is possible to experience, and homelessness creates everyday circumstances that promotes struggling along through the lack of moving forward, of fragmented narratives and isolation.

Counterplay where the author succumbs to his private passion: chess

It is written to portray what it may feel like to be a tournament chess player for an audience that is interested by chess, rather than anthropology. It has analytical sprinklings and pinches of theories but these are short passages, accessible in style and seem illustrative rather than explanatory. The main analytical elements are related to exploring the role of play in chess but also in our everyday life and interaction and the way this is linked with rituals. There 2 extensive look at the psychological and subjective experience of what it is like to play chess at a tournament level through the depiction of 2 games. The descriptions of his mental calculations and the anxious doubting of his abilities is interspersed with exploration of the cognitive processes such as pattern recognition, cognitive switching and subjunctive modes of imaginative thought. Desjarlais explores the tactics that players apply to protect their games and themselves from being read by opponents, something he calls counterempathy, explaining that empathy may not always be perceived as a good think and can be likened to sorcery in view of its definition as the capacity for participating in anothers feelings or ideas. In this way it is best to avoid thinking about a good move too hard in case it is being read and perceived by the opponent. This notion that empathy is an intersubjective action, that it takes both parties to engage and agree for it to be possible is of relevance to the diagnosis process I will be researching. Desjarlais does not discuss directly the role of empathy as a research method for the anthropologist, but there are enough example in his descriptions of games he is involved in, to note that he gained understanding of his opponents and peer chess player through his own emotional and experiential reactions. This is a great read and has re-motivated me to take my chess board out, and I suspect that this book will cross over very well from Desjarlais usual academic audience, where it can be an exemplar for writing ethnography in an accessible way to the chess playing readership whowill enjoy the numerous references and quotes from famous players.

Sensory Biographies where the author returns to Nepal and find his senses again, but this time in words

Desjarlais gathers the life stories of Lamas in a period when the Yolmo people are establishing their identity as distinguished from other Sherpas etc. He looks at how some people tell their lives through the medium of vision metaphors ( mheme) others through auditory metaphors (Kisang). As Mheme gets old he discuss his past in terms of absences and disappearances in language linked to visuality. Kisang talks of the voices that are not there , of the importance of having listened to what people said or not. Kisang was acoustically engaged with the world as Mheme was visually attuned to it. P338 How, in short, do a persons ways of sensing the world contribute to how a person lives and recollect her life? P3

9 My goal here is to understand how sensory modalities and dispositions play themselves out in individual lives, how members of a single society live out different sensory biographies. P4 The work [.] conjoins a person centered approach to Yolmo subjectivities with a discourse-centred one in detailing how communicative practices, ways of speaking and listening, contribute to how people understand and portray their lives and the lives of others. It attend both to the specifics of the lives in question she did this, he felt that, and to the flux of cultural , personal and interpersonal forces that weighed heavily into the dialogic telling of those lives. P6 He notes that his participants did not put forward a life story already formed, reciting a discourse that had been rehearsed through previous telling, but through questions and answers, they needed to be guided in the telling. P23. Is the story as much the work of the interviewer as of the interviewee? How does a life lived with ADHD symptoms, the physicality of ADHD, affect how life is lived and recollected? The recollection itself is then used for evidential purposes to demonstrate ADHD. Is there something in the way people tell their stories that is specific to their physical experience? People have mentioned that they are visual learners, what does that entails, and is that mean that this sense is more important in their experiencing the world? if something is to stay in the memory it must be burned in: only that which never ceases to hurt stays in the memory. P 148 from Nietzsche on the genealogy of morals and Ecce Homo 1887 (1967: 61) New York, Random house.

Overview and relevance to my research.

Desjarlais is one of the foremost phenomenological anthropologists writing today and is inspirations are reflected in the map of influence below. His first influence was Clifford Geertz who he studied under and whilst he moved away from the interpretative methods he may have retained from this mentor an interest in exploring literary styles for the best exposition of his research. In regards to phenomenology he describes his approach as critical phenomenology which attempts to reconcile the phenomenal with the political and take in consideration the broader cultural and economical at play in the formation of a phenomena. Despite the critical element this approach can be criticised as possibly focusing so much on the minutia of everyday life that it misses wider conflicts as I have noted above in relation to gender issues in Shelter Blues and to the potential role of shamans as holder of the establishments status quo. His ethnographic methods in the 3 books reviewed are based on lengthy period of participant-observation combined with the phenomenological techniques of questioning the assumptions (experience in Shelter Blues and trance in Body and Emotion) , bracketing ( what happens if you suspend the assumptions), what do we need to do to consider the phenomenon as a thing ( there is more than one way of being). The running theme in the 3 books is an aim to provide a particular description and understandings of other lifeworlds rather than generalise and come to a universalistic conclusion. He is also consistent in experimenting and adapting his writing styles to discuss the senses from place to place: in Nepal, the senses are expressed through

10 poems/texts/imagination ; in Boston the senses are expressed through visual/architecture; in New York he seems to loose his senses develop further literary techniques to discuss internal thinking and psychological feelings. Desjarlais is very much concerns about the way his writing style effect the message he is trying to convey; sometimes because the people he is writing about may be also his readers , but mostly to remedy the lack of sensory consideration which he credits anthropologists and in particular the use of images ( Body and Emotions) and architectural metaphors (Shelter blues). This wish to bring the ephemeral imagination into his writing can at times make it difficult reading and some of his philosophical musings require tortuous developing to show their relevance. An example from Shelter blues shows him linking the sublime as understood through Kant with homelessness which is at first view incongruous if not misplaced and requires detours through Le Corbusier and Simmels thoughts on ruins amongst other, to propose that the experience of homelessness can not be comprehended in its details by the rest of us and leads to its construction as an animalistic mythology of the underground. This is an important point that can be felt any day in London if you do not avoid to face homeless people, and Desjarlais attempt to highlight it through sensory reflection is admirable and rewarding but requires of the reader active and repeated readings. In contrast Counterplay is a very successful attempt to make an anthropological study more accessible to the general public, or at least to the chess playing public and the fewer theoretical points made are direct, concise and enriching. The example of Kants sublime is again used but this time to an efficient illustrative effect describing the overwhelming sensation felt by chess players when confronted with never ending permutations of game moves. He explores different narratives modes, more associated with fiction writing such as the use to great affect of the second-person you to draw the reader into the tense and at times aggressive world of tournament chess. Phenomenological methods and sensibilities are worth considering as they can add an important mode of inquiry to my research; the descriptive orientations of phenomenological methods have powerful potentials in ethnographic situation and compatible with other theoretical perspectives. The act of suspending judgement found in the phenomenological epoche and the tracing of the practices of every day life of the Actor-Network model, are methodologically similar in temperament; both attempt to rethink the relationship between objectivity and subjectivity. Yet their differing theoretical background will problematise such issues as agency and to paraphrase M. Jackson, I hope the insight will be fruitful whilst I expect the doctrine to may remain a challenge. I wish to return to the potential of phenomenology in researching the experience of adults with ADHD. Epoche is an important methodological concept in phenomenology and has been summarised as the bracketing of reality, distancing oneself and putting aside assumptions. The bracketing of the truth and untruths of ADHD provides an entry point to how ADHD is experienced as a reality of every day life and how sufferers create meanings out of these experiences. The debates and contestations within the scientific community and the public at large are so loud that they can obfuscate the voice of the patients; in view of my collaboration with a patient organisation, focusing on patients experience of ADHD including physical sensations, has the potential to empower and amplify their voice in their dealings with policy making

11 institutions. In particular, great emphasis is given to neuro-scientific explanations within the scientific and research community and bringing to the forth the practical experience of patients can provide a counterview to the brain hegemony and highlighting that ADHD is not all in the mind but also in the bruises, insomnia and anxiety attacks. Whilst bracketing may facilitate a particular and less explored view of ADHD, my position as a researcher vis--vis the brackets is problematic; is the researcher to be kept out of the bracket and claims a total objectivity or to be integrated within the backer and turn native? It is more likely that an in-between position would bring more benefits but the difficulty is to go back and forth, within and without of the bracket to allow oneself to share and give credit to the experience of the participants and to apply anthropological knowledge in analysing the experience. This may be conducive to a respectful rapport with participant and lead to what Harry West described in the contexts of sorcery as believing a little bit, leaving space for the uncertain and not reducing the experience of others as constructed. In my contact with sufferers in support groups I have been asked many times what position I took, does ADHD exist or does it not, and as I got to know participants and their stories my answer became more confident that, in them it did exist echoing implicitly Wests motto. Caveat: In whatever situation I will find myself during fieldwork, in the clinic, in the support group or with scientists can I experience ADHD? I may observe what it is like to go through the diagnostic process from a patient and a doctors point of view and gain understanding of their experience, a once-removed experience. I could experience the treatments prescribed, both psycho-social and pharmaceutical, but the effect is unlikely to be similar with the patients. What about the symptomatic experience? As unexpected as it seems, as it would not seem possible nor welcomed to experience illnesses, such as cancer or Alzheimer for researchs sake in the case of ADHD this may be worth exploring by keeping ones mind open. The symptoms are commonly described as a matter of degree and accumulation which means that most people can relate to them; forgetfulness, disorganisations, loss of sense of time, impulsivity are not totally alien concept and some insight may be gained by reflecting on ones experience of them. Yet experience in itself is not the panacea of social science research; as Desjarlais demonstrates in Shelter blues, the concept of experience itself is socially and historically constructed and it is the context in which ADHD sufferers operate and create meanings as much as their experience that I will need to pay attention to. This research agenda has its own obstacles, common to most ethnographical inquiry, as some contexts will be more open to me such as the public arenas of medical debates or public health politics than the private circumstances of education, employment, family life. The extents to which I will be a participant in any of these fields remain uncertain and limited, but at this pre-fieldwork stage I wish to remain open to possibilities.

12

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Healthy Cooking Oil from RiceDocumento7 pagineHealthy Cooking Oil from Ricehusainkabir63_113901Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jung and The OtherDocumento113 pagineJung and The OtherEtel AdlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Schoolarship Exam MCQsDocumento12 pagineSchoolarship Exam MCQsSaber AlasmarNessuna valutazione finora

- ADHD Guidance-September 2013Documento6 pagineADHD Guidance-September 2013Claude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Kleinman, Suffering and Its Professional Transformation PDFDocumento27 pagineKleinman, Suffering and Its Professional Transformation PDFrachel.aviv100% (2)

- Deep Bite (Dental Update)Documento9 pagineDeep Bite (Dental Update)Faisal H RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul Stange - The Logic of Rasa in JavaDocumento22 paginePaul Stange - The Logic of Rasa in JavaMao Zen BomNessuna valutazione finora

- Ayahuasca Experience and Mythical Perception 2Documento27 pagineAyahuasca Experience and Mythical Perception 2Nima GhasemiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Work of Emotion: Ballard and The Death of Affect (Part 1)Documento11 pagineThe Work of Emotion: Ballard and The Death of Affect (Part 1)Jon Moodie100% (1)

- Twelve StepsDocumento4 pagineTwelve StepsJohn MichaelNessuna valutazione finora

- 16 2 RatcliffeDocumento16 pagine16 2 RatcliffeguusboomNessuna valutazione finora

- Personality. The Individuation Process in the Light of C. G. Jung's TypologyDa EverandPersonality. The Individuation Process in the Light of C. G. Jung's TypologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Totem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodDa EverandTotem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Tooth PreparationDocumento46 paginePrinciples of Tooth PreparationSukhjeet Kaur88% (8)

- Six Realms of ConsciousnessDocumento12 pagineSix Realms of ConsciousnessBenStappNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalysis, Suffering, Symptoms and the Experience of DeterminationDocumento19 paginePsychoanalysis, Suffering, Symptoms and the Experience of DeterminationChristian DunkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivational Enhancement TherapyDocumento9 pagineMotivational Enhancement TherapyDavid Alejandro VilledaNessuna valutazione finora

- Myth in WastelandDocumento6 pagineMyth in WastelandDejan Ejubovic100% (1)

- Summary of Jung's ThoughtDocumento6 pagineSummary of Jung's ThoughtnamkvalNessuna valutazione finora

- Avens1977-ImageDevil CGJungs PsychologyDocumento27 pagineAvens1977-ImageDevil CGJungs PsychologyAbdul Ajees abdul SalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Dorothea Elizabeth Orem: Self-Care TheoryDocumento3 pagineDorothea Elizabeth Orem: Self-Care TheoryE.R.ONessuna valutazione finora

- Dane Rudhyar - The Pulse of Life PDFDocumento81 pagineDane Rudhyar - The Pulse of Life PDFFilipe Sales100% (3)

- Varieties of Tulpa Experiences The HypnoDocumento23 pagineVarieties of Tulpa Experiences The HypnolucasNessuna valutazione finora

- Halifax 1990Documento9 pagineHalifax 1990parra7Nessuna valutazione finora

- GMC Official PLAB 1 Question SampleDocumento8 pagineGMC Official PLAB 1 Question Samplemuntaser100% (1)

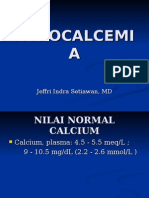

- HYPOCALCEMIADocumento27 pagineHYPOCALCEMIAJeffri SetiawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Depression, Emotion and the Self: Philosophical and Interdisciplinary PerspectivesDa EverandDepression, Emotion and the Self: Philosophical and Interdisciplinary PerspectivesNessuna valutazione finora

- Storytelling and HealingDocumento6 pagineStorytelling and HealingproffenklNessuna valutazione finora

- A History of Midwifery and Its Role in Women's HealthcareDocumento42 pagineA History of Midwifery and Its Role in Women's HealthcareAnnapurna Dangeti100% (4)

- Living at the Edge of Chaos: Complex Systems in Culture and PsycheDa EverandLiving at the Edge of Chaos: Complex Systems in Culture and PsycheValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- Martha C. Nussbaum - Précis of Upheavals of ThoughtDocumento7 pagineMartha C. Nussbaum - Précis of Upheavals of Thoughtahnp1986Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dane Rudhyar - The Pulse of LifeDocumento81 pagineDane Rudhyar - The Pulse of LifeGabriela Magistris100% (1)

- Review of DesjarlaisDocumento3 pagineReview of DesjarlaisHildon CaradeNessuna valutazione finora

- Hermeneutics of Daily Life. Remorse and Resentment (RR, R) - Crystallization of The SelfDocumento11 pagineHermeneutics of Daily Life. Remorse and Resentment (RR, R) - Crystallization of The SelfMensurMrkvićNessuna valutazione finora

- Grief, Rage and Headhunting in the PhilippinesDocumento2 pagineGrief, Rage and Headhunting in the PhilippinesIqbalNessuna valutazione finora

- (David - Sibley) - Geographies - of - Exclusion-Chapter 2Documento18 pagine(David - Sibley) - Geographies - of - Exclusion-Chapter 2Reid StephensNessuna valutazione finora

- Suffering and Healing, Subordination and Power: Women and Possession TranceDocumento18 pagineSuffering and Healing, Subordination and Power: Women and Possession TrancePanosNessuna valutazione finora

- DARK OF THE SOUL GUIDE TO PSYCHOPATHOLOGYDocumento7 pagineDARK OF THE SOUL GUIDE TO PSYCHOPATHOLOGYla vie est rougeNessuna valutazione finora

- Becoming Basic Considerations For A Psychology of Personality. GORDON W. ALLPORT.Documento5 pagineBecoming Basic Considerations For A Psychology of Personality. GORDON W. ALLPORT.CC TANessuna valutazione finora

- Temporal Dimensions of Selfhood: Theories of Person Among The Suruí of Rondônia (Brazilian Amazon)Documento18 pagineTemporal Dimensions of Selfhood: Theories of Person Among The Suruí of Rondônia (Brazilian Amazon)Luis Alfredo Soares FalcãoNessuna valutazione finora

- Totem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksDa EverandTotem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksNessuna valutazione finora

- Karen Horney's Theory of Alienation and NeurosisDocumento12 pagineKaren Horney's Theory of Alienation and NeurosisfridayantiNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer - Asp 5Documento5 pagineContentServer - Asp 5Cezara DragomirNessuna valutazione finora

- Under Saturn, in Three LanguagesDocumento13 pagineUnder Saturn, in Three LanguagesLucas sNessuna valutazione finora

- Vol13 No1 2017 Trauma and Counter Trauma Emanuel 655 2605 1 PB UatvwvDocumento20 pagineVol13 No1 2017 Trauma and Counter Trauma Emanuel 655 2605 1 PB UatvwvDavid EinsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Collective UnconsciousDocumento4 pagineCollective UnconsciousPriestess AravenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 11Documento17 pagineSession 11EH VIDEOs VGNessuna valutazione finora

- Everyday Dissociations ButlerDocumento11 pagineEveryday Dissociations ButlerkatiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things: Traumatic Distress in ChildrenDocumento4 pagineArundhati Roy's The God of Small Things: Traumatic Distress in ChildrenIJELS Research JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Fear of responsibility and desacralization of lifeDocumento7 pagineFear of responsibility and desacralization of lifeOnin GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- First-Order and Second-Order SufferingDocumento16 pagineFirst-Order and Second-Order Sufferingmarcelo DuarteNessuna valutazione finora

- EmptinessDocumento5 pagineEmptinesscabezadura2Nessuna valutazione finora

- InflexionsDocumento11 pagineInflexionsGreiner ChristineNessuna valutazione finora

- TOTEM & TABOO: Resemblances between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodDa EverandTOTEM & TABOO: Resemblances between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Feeling Brown Feeling DownDocumento15 pagineFeeling Brown Feeling DownNina HoechtlNessuna valutazione finora

- Etho 12254Documento14 pagineEtho 12254Sasha PozelliNessuna valutazione finora

- Sennett - Richard Authority W. W. Norton - Company - 1993Documento175 pagineSennett - Richard Authority W. W. Norton - Company - 1993Pedro RafaelNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Carl Jung's Concept of the Collective UnconsciousDocumento24 pagineUnderstanding Carl Jung's Concept of the Collective UnconsciousRista SeptianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Erika Bourguignon Multiple Personality Possession Trance and The Psychic Unity of Mankind 1 PDFDocumento15 pagineErika Bourguignon Multiple Personality Possession Trance and The Psychic Unity of Mankind 1 PDFJavier MonteroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Phenomenology of TraumaDocumento4 pagineThe Phenomenology of TraumaMelayna Haley0% (1)

- Reflections On Women, Depression, and The Soul-Image: by Karen HodgesDocumento36 pagineReflections On Women, Depression, and The Soul-Image: by Karen HodgesAndrew HartmanNessuna valutazione finora

- DoppelgängerDocumento11 pagineDoppelgängerMaria PucherNessuna valutazione finora

- Psyche of Serial & Mass Killers.v2Documento35 paginePsyche of Serial & Mass Killers.v2chiqui1025Nessuna valutazione finora

- Experiencing Alterity and IdentityDocumento4 pagineExperiencing Alterity and IdentityHuguesNessuna valutazione finora

- TA and Spirituality Kandathil & Kandathil (1997)Documento4 pagineTA and Spirituality Kandathil & Kandathil (1997)melpomena81Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fredrik Svenaeus - The Body As Alien, Unhomelike, and Uncanny Some FurtherDocumento4 pagineFredrik Svenaeus - The Body As Alien, Unhomelike, and Uncanny Some FurtherBrenda RossiNessuna valutazione finora

- Freud and ReligionDocumento5 pagineFreud and ReligionKeerthana KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring Attitudes To-Wards Death and Life Through Story and Meta - Phor Zvi Bellin, PH.D Loyola University, MarylandDocumento11 pagineExploring Attitudes To-Wards Death and Life Through Story and Meta - Phor Zvi Bellin, PH.D Loyola University, MarylandInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Claude Jousselin Soc of DX BlogDocumento3 pagineClaude Jousselin Soc of DX BlogClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Foley's Eki PDFDocumento463 pagineFoley's Eki PDFClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Centre of The BodyDocumento1 paginaCentre of The BodyClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult ADHD UK Support Groups SurveyDocumento19 pagineAdult ADHD UK Support Groups SurveyClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Memoire Oubli Histoire RicoeurDocumento2 pagineMemoire Oubli Histoire RicoeurClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- ADHD Medication and CrimeDocumento2 pagineADHD Medication and CrimeClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Imaging technologies and the diagnosis of Adult ADHD in the UKDocumento1 paginaImaging technologies and the diagnosis of Adult ADHD in the UKClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Remembering Turbulent Times: Accounting For Adult ADHD Through The Reconstruction of ChildhoodDocumento10 pagineRemembering Turbulent Times: Accounting For Adult ADHD Through The Reconstruction of ChildhoodClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucille and Band Performing at Music For Youth March 2013Documento1 paginaLucille and Band Performing at Music For Youth March 2013Claude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- ADHD BackgroundDocumento10 pagineADHD BackgroundClaude JousselinNessuna valutazione finora

- Type III Radix Entomolaris in Permanent Mandibular Second MolarDocumento3 pagineType III Radix Entomolaris in Permanent Mandibular Second MolarGJR PUBLICATIONNessuna valutazione finora

- Pros and cons of experimental medical treatmentsDocumento3 paginePros and cons of experimental medical treatmentskingfish1021Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cervical Radiculopathy With Neurological DeficitDocumento5 pagineCervical Radiculopathy With Neurological DeficitHager salaNessuna valutazione finora

- Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection: Team 3: Cercado, Chiong, EsperidaDocumento28 pagineCentral Line Associated Blood Stream Infection: Team 3: Cercado, Chiong, EsperidaJuniferNessuna valutazione finora

- First Aid Manual Rev 0Documento77 pagineFirst Aid Manual Rev 0Vinayak KaujalgiNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE REPORT-Devyana Enggar TaslimDocumento24 pagineCASE REPORT-Devyana Enggar TaslimvivitaslimNessuna valutazione finora

- AlietalDocumento11 pagineAlietalOana HereaNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiology of LaborDocumento49 paginePhysiology of LaborGunung MahameruNessuna valutazione finora

- Ketorolac vs. TramadolDocumento5 pagineKetorolac vs. TramadolRully Febri AnggoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Reid BrochureDocumento2 pagineReid Brochureapi-309993302Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Tetanus?: Clostridium Tetani or The Tetanus Bacillus Is A Slender, Gram-Positive, Anaerobic Rod That MayDocumento5 pagineWhat Is Tetanus?: Clostridium Tetani or The Tetanus Bacillus Is A Slender, Gram-Positive, Anaerobic Rod That MayraechcmNessuna valutazione finora

- Control of Odors in The Sugar Beet Processing Industry: Technical PaperDocumento7 pagineControl of Odors in The Sugar Beet Processing Industry: Technical PaperIrvan DwikiNessuna valutazione finora

- FDA Approved Drug Products 29th Edition Cumulative Supplement 02Documento44 pagineFDA Approved Drug Products 29th Edition Cumulative Supplement 02Narottam ShindeNessuna valutazione finora

- NCP-Risk For InfectionDocumento2 pagineNCP-Risk For InfectionJea Joel Mendoza100% (1)

- B. Braun Water TreatmentDocumento48 pagineB. Braun Water TreatmentMedical TechniciansNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Meeting for PEG Tube PlacementDocumento315 pagineFamily Meeting for PEG Tube PlacementSuggula Vamsi KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dangers of Hydrogen SulfideDocumento4 pagineDangers of Hydrogen SulfideLilibeth100% (1)

- MCQDocumento6 pagineMCQalirbidiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 4 Part 1 PDFDocumento11 pagineLecture 4 Part 1 PDFBashar AntriNessuna valutazione finora

- Nine Steps To Occlusal Harmony FamdentDocumento5 pagineNine Steps To Occlusal Harmony FamdentGhenciu Violeta100% (1)

- Vinyl Catalog and Technical Information 2019Documento245 pagineVinyl Catalog and Technical Information 2019prateekmuleNessuna valutazione finora