Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sydney 2030 Plan - An Analysis of The Potentials and Shortcomings of Direction 4: A City For Pedestrians and Cyclists.

Caricato da

Guillermo UmañaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Sydney 2030 Plan - An Analysis of The Potentials and Shortcomings of Direction 4: A City For Pedestrians and Cyclists.

Caricato da

Guillermo UmañaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Guillermo Umana Macquarie University ENV267

Sydney 2030 Plan An analysis of the potentials and shortcomings of Direction 4: A City for Pedestrians and Cyclists.

1. Introduction

The City of Sydney 2030 Plan was created in 2008 after almost two years of intense consultation with the community, government agencies and the private sector. The result is a very comprehensive strategy to guide Sydney towards becoming a more sustainable and livable city. As it will be argued throughout this paper, the Sydney 2030 Plan has a high potential for success because of its comprehensive consultation process, its allencompassing objectives and its transparency and accountability. This paper will focus particularly on Direction 4 of the Sydney 2030 Plan, namely A City for Pedestrians and Cyclists. This Direction is one of the ten Strategic Directions that will guide Sydney towards a more Global, Green and Connected city (City of Sydney, 2008). The importance of Direction 4 is that its objectives are completely linked to the objectives of other directions in the Plan (City of Sydney, 2010). Although there is a high potential for success, truly making Sydney a city for pedestrians and cyclists is not an easy task. Impediments exist in terms of getting funding and approvals from different levels of government; especially those with different priorities from the ones of the City of Sydney. The reality of politics must be dealt with by Sydney Council to make sure that Direction 4 and all other directions of The Plan will be achieved successfully.

2. Current State of the City of Sydney

Today almost 50% of the trips around the Sydney LGA are made by walking and cycling, compared to only 20% in the Greater Metropolitan Sydney (City of Sydney, 2010). This

1

numbers reflect the relative advantage of Sydney compared to other LGAs to implement sustainable ways of transport. Cycling and walking can generate multiple social and economic benefits to the city, such as healthier residents, a more dynamic local economy and international recognition (Cervero, 2003). Clover Moore (in Moore et al, 2009) states that even today, the commuters that arrive to the City of Sydney by car become pedestrians when they get to the city, which gives Direction 4 of the Plan a high potential for success.

The financial state of the City of Sydney Council also poses a potential for the success for Direction 4. The 2012s Resourcing Strategy (City of Sydney, 2012: 8) states that the council has for many years maintained a high level of control over its financial position and performance, and this has been continually demonstrated though its strong operating results. Making Sydney a city for pedestrians and cyclists means that big infrastructure projects must be approved to provide people with safe environments for walking and cycling, and the need for a healthy financial state of the local council is essential. The construction of the 200Km cycleways network, local plazas and the greening of pedestrian corridors (as shown in Map 1) will need federal and state funding, because making allencompassing physical changes is expensive. Only the renewal of Green Square public areas is valued in the order of $350M over the next ten years (City of Sydney, 2012). This project currently needs the approval and consultation of more than 10 government agencies, which makes the process slow and bureaucratic. Reform to create a single sustainable transport agency for the City of Sydney is needed to make Direction 4 of the 2030 Plan be effective. But the creation of such an agency takes time, as the NSW planning system is currently highly centralized around the State Department of Planning (Gunningham et al., 2007). A decentralization of the system would allow the City of Sydney to make decisions without the checks and balances from an unnecessary number of agencies. But if the City wants to achieve Direction 4 objectives by 2030, it will have to work within the current system, because a decentralization process is an uncertain and time-consuming process (Gunningham et al., 2007).

Map 1: A city for Pedestrians and Cyclist map (Copied from: City of Sydney, 2008: 33)

3. The Importance of working together with the community

The OECD handbook of governance and policy-making states that governments should be prepared to embrace criticism, should be accountable and should engage with unsolicited feedback to engage positively in consultation processes (Gramberger, 2001). The importance of transparency and inclusion of all stakeholders, even the ones that go against the interests of the government, are especially important when dealing with long term strategic plans, such as the Sydney 2030 Plan, because having everyone on board at the start will prevent delays in future deliveries.

The City of Sydney took the consultation process for its 2030 Plan to a level that few local councils in Australia have reached. The City of Sydney Community Strategic Plan (2010: 193

25) explains that consultation began in June 2007 and continued throughout 2008, a period in which a full spectrum of interested groups and individuals, including school children, young people, business leaders, artists, educators, community activists, residents, shop keepers, small businesses, councillors, church and sporting groups were consulted. In total, 12,000 people were directly consulted at more than 30 community forums and more than 6,000 people gave comments at the regular City Talk events organised by the council. 19,000 people used the citys Future Phone at schools and institutions and 157,000 people visited the Sydney 2030 Vision Exhibition at the Customs House during 2008. The number of people consulted is incredibly high taking into account that according to the 2011 census, the City of Sydney LGA had a population of 183,494 (City of Sydney Website, 2012).

Graph A: Number of Submissions to the Sydney 2030 Plan per Key Direction (Copied from: City of Sydney, 2008: 196)

As shown in Graph A (above), Direction 4 was the third direction with more submissions during consultation after the Integrated Transport and Lively and Engaging City directions. This shows that residents of the City of Sydney are particularly interested in the importance of sustainable transport to make Sydney a more liveable city. The consultation results show that there is community support for cycling and walking to replace motorised transportation in the city, and this is a potential for success.

But the community was not the only stakeholder consulted. The Lord Mayor, the Citys Chief Executive and members of the City Strategic Team had regular meeting with Local, State and Federal Government leaders and business executives during the consultation period (City of Sydney, 2010). The fact that the Council was engaged with the community, the private sector and the public sector from an early stage, gives a higher potential of success to the objectives of the 2030 Plan. Jan Gehl (2012: minute 9), one of the designers of The Plan, argues that in the past Sydney, as many cities in the world, has been run, not by a major but by a group of transport lobbyists and that this mentality is slowly dying as the city is reconquered by the community. Here lies the importance of an all-encompassing consultation process in which opinions from individuals are weighted equality as the views from businesses and other branches of government.

Anyhow, unexpected stakeholders appear when big projects, such as the Liveable Green Corridors are built (Spinney, 2010). This makes it necessary that the Council engages in an ongoing consultation process. A one-off consultation is not effective in the long run and the City of Sydney must have this into account. A pedestrian and cyclist culture must be created. But to change culture, it is essential for Sydney to work together with its people. Mockus (2012) explains that for a city to effectively change peoples behaviours, it needs to work towards changing the citizenship culture. In Sydney it is evident that the culture is already changing as its citizens are becoming more aware of the importance of walking and cycling. The City should embrace this fact to make Direction 4 successful in the long run.

4. Importance of working together with all levels of government

Arguably the most important drawback for the implementation of Direction 4 is the importance of working together with all levels of government to achieve the objectives of making Sydney a friendlier place for pedestrians and cyclists. Clover Moore (2009) has firmly stated that the City of Sydney is working towards including surrounding councils to seek together national and state funding for cycling projects. At the moment of writing this paper, Anthony Albanese in behalf of the Australian Council of Local Governments gave his support to the City of Sydney to make George Street a pedestrian-only road. At the same time,

5

Infrastructure NSW publicly opposed the project to make George Street car-free and proposed to build an underground bus interchange (Herald Sun, 2012). The Mayor, Clover Moore, opposed the proposal of Infrastructure NSW by saying that it goes against the 2030 Plan objectives. This ongoing discussion between the multiple government agencies with an agenda on this matter makes it clear that working with different levels of governments is not an easy task.

At the moment too many agencies are involved in pedestrian and cyclist projects in Sydney, and therefore the importance of creating a single agency that fast-tracks agreements and pushes towards a single agenda with long-term objectives. The success of Direction 4 partially lies on the speed in which agreements can be made. Currently the council has had to deal with the RTA, the STA Minister for Transport, the Taxi Council, the Police, RailCorp, Bus Operators, Bike NSW, Pedestrian Council NSW, the Department of Planning, Barangaroo Development Authority and the Redfern-Waterloo Authority to start implementing Direction 4 objectives (Moore, 2009). This has taken longer than the council expected. Gunnigham et al. (2007) argue that a decentralized planning system is an option to empower the community and allow local governments to have their own legislative design to fast track projects which are beneficial to the community. Changing the system will take long and will create a lot of uncertainties. The truth is that at the heart of Global Sydney, the City of Sydney has all eyes set on it, and therefore all government agencies have an interest in it. This is inevitable, and the 2030 Plan will have to be delivered having this fact into account.

5. Conclusions

This paper has shown that the effort and preparation that the City of Sydney has put into making its 2030 Plan as transparent, inclusive of all stakeholders and detailed, gives Direction 4: A city for Pedestrians and Cyclists a big potential for success. The current state of the City reflects that there is community support for Direction 4 of The Plan and that changes towards sustainable transport modes are already happening. On top of this, the

financial state of the Council is positive and its relation to local businesses is beneficial to combine social and economic strategies with cycling and pedestrian strategies.

It is evident that the most important drawback for making Sydney a city for pedestrians and cyclists is the need for funding and approval from other government agencies. Reform to create a single sustainable transport agency for the City of Sydney is needed to make Direction 4 of the 2030 Plan effective. But the creation of such an agency takes time. A decentralization of the system would allow the City of Sydney to make decisions without checks and balances from an unnecessary number of agencies, but the creation of a new planning system is uncertain so if the City wants to achieve Direction 4 objectives by 2030, it will have to work within the current system. The City will have to maintain an ongoing consultation process to make sure the interests of all stakeholders will still be taken into account as projects unfold. A good relation of the Council with other State and Federal agencies is necessary for Direction 4 to be a success, as its projects completely depend on state and federal funding and the approval from a number of agencies.

References

Cervero, R., (2003), Green Connectors: Off-shore Examples, American Planning Association, Volume: May 2003. City of Sydney, (2008), Sustainable Sydney 2030: The Vision Snapshot, accessed 30 September 2012 summary.pdf> <https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cityofsydney/2030/documents/2030-Vision-

City of Sydney, (2010), Sustainable Sydney 2030, accessed 30 September 2012, <https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cityofsydney/2030/documents/2030-Vision-Complete.pdf> City of Sydney (2011), State of the City 2011, accessed 30 September 2012, <https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cityofsydney/2030/documents/State-of-the-City-report2011.pdf>

City of Sydney (2012A), Resourcing Strategy 2012, accessed 30 September 2012 <http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Council/documents/IntegratedPlanningReporting/2012/ Resourcing-Strategy-2012.pdf>

City of Sydney (2012B), Sydney Corporate Plan, accessed 30 September 2012, <http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Council/documents/IntegratedPlanningReporting/2012/ Corporate-Plan-2012-15-2012-Revision.pdf>

City

of

Sydney

Website

(2012),

Community

Profile,

accessed

October

2012

<http://profile.id.com.au/sydney/home> Gramberger, M., (2001), Citizens as Partners: OECD Handbook on Information, Consultation and Public Participation in Policy-making, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Governance Handbook, Pages 15-79. Gunningham, N., Holley, C., Shearing, C., (2007), Neighbourhood Environment Improvement Plans: Community Empowerment, Voluntary Collaboration and Legislative Design,

Environmental and Planning Law Journal, Vol. 24(2), Pages 9-25. Herald Sun, (2012), Sydney Major Slams Underground Project, accessed October 4, 2012, <http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/breaking-news/sydney-mayor-slams-undergroundproject/story-e6frf7kf-1226487483070> Jan Gehl Talk (2012), Creating a Great Pedestrian City, City of Sydney Talks Podcast, accessed 30 September 2012, < http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/podcasts/citytalks/Creating-a-GreatPedestrian-City.asp> Mockus, A., (2012), Building Citizenship Culture in Bogota, Journal of International Affairs, Volume 65, no 2 Moore, C, Albanese, A, Livingstone K, (2009), Integrated Transport for a Connected City, City of Sydney Talks Podcast, accessed 30 September 2012,

<http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/podcasts/citytalks/IntegratedTransport.asp> Spinney J., (2010), Performing resistance? Re-reading practices of urban cycling on London's South Bank, Environment And Planning A, 2012, volume 42. Johnson, P, J., Krizek, K, J., (2006), Proximity to Trails and Retail: Effects on Urban Cycling and Walking, Journal of the American Planning Association, Volume 72, no 1.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Lesson 1 Human Cultural Variations, Social Differences, Social Change and Political IdentitiesDocumento29 pagineLesson 1 Human Cultural Variations, Social Differences, Social Change and Political Identitiesjay jay86% (77)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- JZ Letter To Crown PrinceDocumento5 pagineJZ Letter To Crown PrinceSundayTimesZA75% (4)

- Challenges and Futures For Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) in LocalGovernmentDocumento6 pagineChallenges and Futures For Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) in LocalGovernmentGuillermo UmañaNessuna valutazione finora

- Snowy River Environmental Flows Report 2012Documento12 pagineSnowy River Environmental Flows Report 2012Guillermo UmañaNessuna valutazione finora

- Moving Away From A Categorical Approach To Power and Closer To Arelational Understanding of Power in The Colombian Coal Mine of El CerrejónDocumento12 pagineMoving Away From A Categorical Approach To Power and Closer To Arelational Understanding of Power in The Colombian Coal Mine of El CerrejónGuillermo UmañaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sydney Urban Issues, Changes and SolutionsDocumento13 pagineSydney Urban Issues, Changes and SolutionsGuillermo Umaña100% (5)

- Planning Philosophies in 20th Century AustraliaDocumento3 paginePlanning Philosophies in 20th Century AustraliaGuillermo UmañaNessuna valutazione finora

- EFA, A Critical Review Based On Sutcliffe Et. Al (2008)Documento5 pagineEFA, A Critical Review Based On Sutcliffe Et. Al (2008)Guillermo UmañaNessuna valutazione finora

- WHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY - Richard HeinbergDocumento12 pagineWHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY - Richard HeinbergPost Carbon InstituteNessuna valutazione finora

- Notice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Bear Butte National Wildlife Refuge, SD Comprehensive Conservation PlanDocumento1 paginaNotice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Bear Butte National Wildlife Refuge, SD Comprehensive Conservation PlanJustia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Micro-Environment (Near Environment) : MarketingDocumento5 pagineMicro-Environment (Near Environment) : Marketingbrindhalal13Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 1226-2016.4.27 Joel Gilbert Update To AJE About Tarrant Ramping Down and Expansion To Kingston and Norwood-HighlightedDocumento2 pagineExhibit 1226-2016.4.27 Joel Gilbert Update To AJE About Tarrant Ramping Down and Expansion To Kingston and Norwood-HighlightedAnonymous Yxs1MUgNessuna valutazione finora

- Rain Water Harvesting by Freshwater Flooded ForestsDocumento5 pagineRain Water Harvesting by Freshwater Flooded ForestsN. SasidharNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Interviews - Tio Nanda EditDocumento8 pagineList of Interviews - Tio Nanda EditYonatan KurniawanNessuna valutazione finora

- ReviewerDocumento25 pagineReviewerJohn Rey Almeron Serrano100% (1)

- Why Don't Teams Work Like They're Supposed ToDocumento8 pagineWhy Don't Teams Work Like They're Supposed ToDS0209Nessuna valutazione finora

- Health, Safety and Environmental Management System ManualDocumento92 pagineHealth, Safety and Environmental Management System ManualAlwyn Tauro100% (1)

- How Do Mixed-Heritage Individuals Make Sense of Ethnic and Cultural Identity in Everyday Life? Perspectives From Personal and Social Interactions. (Rajan)Documento30 pagineHow Do Mixed-Heritage Individuals Make Sense of Ethnic and Cultural Identity in Everyday Life? Perspectives From Personal and Social Interactions. (Rajan)Anonymous Ypde4DaNessuna valutazione finora

- DM Plan Jamalpur Sadar Upazila Jamalpur District - English Version-2014Documento165 pagineDM Plan Jamalpur Sadar Upazila Jamalpur District - English Version-2014CDMP BangladeshNessuna valutazione finora

- N. Mason Cummings - Indigenous Identity On The World Stage - The Mentawai of IndonesiaDocumento8 pagineN. Mason Cummings - Indigenous Identity On The World Stage - The Mentawai of IndonesiaHasriadi Ary MasalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalisation, Cosmopolitanism and EcologicalDocumento16 pagineGlobalisation, Cosmopolitanism and EcologicalRidhimaSoniNessuna valutazione finora

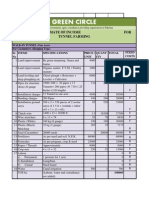

- 0321-8669044 Tunnel Farming in Pakistan Feasibility Walk-In Medium Tunnel 2012 by Green CircleDocumento3 pagine0321-8669044 Tunnel Farming in Pakistan Feasibility Walk-In Medium Tunnel 2012 by Green CircleSajid Iqbal SandhuNessuna valutazione finora

- PESA DP KamberShahdadKot SindhDocumento58 paginePESA DP KamberShahdadKot SindhSyedShahzadHasanRizviNessuna valutazione finora

- NATRESDocumento33 pagineNATRESAleezah Gertrude RaymundoNessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Factors That Are Larger Societal Forces Affecting Your CompanyDocumento3 pagineEnvironmental Factors That Are Larger Societal Forces Affecting Your CompanySuryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Demand Side Management and Its ProgramsDocumento15 pagineDemand Side Management and Its ProgramsAhmad H Qinawy100% (1)

- CausesOfUndernutritioninChildrenunderfive SierraLeoneDocumento38 pagineCausesOfUndernutritioninChildrenunderfive SierraLeoneyayuk dwi nNessuna valutazione finora

- CDP+ LCCAP Mentoring - Samar1Documento42 pagineCDP+ LCCAP Mentoring - Samar1Boris Pineda Pascubillo100% (1)

- Greta Thunberg Reading Comprehension TextDocumento3 pagineGreta Thunberg Reading Comprehension TextGabriel OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 5 Attitude ChangeDocumento26 pagineLecture 5 Attitude ChangemahmialterNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecofeminism Women SpiritualitychapteroneDocumento13 pagineEcofeminism Women SpiritualitychapteroneDDKNessuna valutazione finora

- Determination Sustainability Status in Urban Infrastructure (Case Study: Bandarlampung City)Documento11 pagineDetermination Sustainability Status in Urban Infrastructure (Case Study: Bandarlampung City)WizeNessuna valutazione finora

- CI LandscapeDocumento73 pagineCI LandscapePawanKumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme CourtDocumento18 pagineSupreme CourtNewsclickNessuna valutazione finora

- Exid Group Company Limited: Tender Name Water Supply Measurement DetailDocumento6 pagineExid Group Company Limited: Tender Name Water Supply Measurement DetailMin Chan MoonNessuna valutazione finora

- United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change (Unfccc) and Role of United States of AmericaDocumento8 pagineUnited Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change (Unfccc) and Role of United States of AmericaIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora