Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

(129 - 159) + (M3)

Caricato da

Justin CebrianDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

(129 - 159) + (M3)

Caricato da

Justin CebrianCopyright:

Formati disponibili

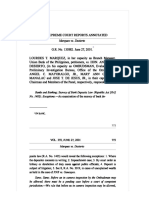

PEOPLE V.

RIO 201 SCRA 702 (1991) FACTS: Ricardo Rio was convicted of rape and sentenced to reclusion perpetua by the trial court. He filed an appeal and as such, the records of the case were forwarded to the Court of Appeals who then promptly sent it to the Supreme Court in view of the penalty imposed upon him. In the course of events, Rio filed a motion to withdraw his appeal due to his poverty. The Court denied Rio's motion and appointed a counsel de oficio for him. ISSUE: This is a rape case. The main issue here is obviously irrelevant to our discussion. Instead, we focus on the constitutional mandate set forth in Article III, Sec. 11. RULING: The Court opined that Rio seemed unaware that the former can appoint a counsel de oficio to prosecute the latters appeal pursuant to Rule 122 of the Rules of Court (the rules governing appeal) and Art. III, Sec. 11. Lets have a little backgrounder (based on Mr. Justice Malcolms writings): Two of the basic privileges of the accused in a criminal prosecution are (1) the right to the assistance of counsel and (2) the right to a preliminary examination. Pres. McKinley made the first right a part of the US Organic Law by imposing the inviolable rule that [the accused] shall enjoy the right to have assistance of counsel for the defense. Said right, described by Judge Cooley as perhaps the privilege most important to the person accused of crime is now enshrined in our Constitution as Sec. 11 of Art. III. In criminal cases there can be no fair hearing unless the accused be given an opportunity to be heard by counsel. The right to be heard would be of little meaning if it does not include the right to be heard by counsel. The right to counsel de oficio does not cease upon the conviction of an accused by a trial court. It continues, even during appeal, such that the duty of the court to assign a counsel de oficio persists where an accused interposes intent to appeal. Even in a case where the accused has signified his intent to withdraw his appeal, the court is required to inquire into the reason for the withdrawal. Where it finds the sole reason for the withdrawal to be poverty, as in this case, the court must assign a counsel de oficio, for despite such withdrawal, the duty to protect the rights of the accused subsists and perhaps, with greater reason. In this spirit, the Court ordered the appointment of a counsel de oficio for Rio. (It did not turn out well.) ESCOBEDO V. ILLINOIS 378 U.S. 478, 12 L Ed 2d 977, S4 S Ct 1758 (1974) FACTS: Danny Escobedo's brother-in-law, Manuel, a convict from Chicago, was shot and killed on the night of January 19, 1960. Danny Escobedo was arrested without warrant early the next morning and interrogated. However, Escobedo made no statement to the police and was subsequently released that afternoon. Subsequently, Benedict DiGerlando, who was in custody and considered another suspect told the police that indeed Escobedo fired the fatal shots because the victim had mistreated Escobedo's sister. On January 30, the police arrested Escobedo again this time with his sister, Grace. While transporting them to the police station, the police explained that DiGerlando had implicated Escobedo, and urged

him and Grace to confess. Escobedo again declined. Escobedo asked to speak to his attorney, but the police refused, explaining that although he was not formally charged as of yet, he was in custody and could not leave. His attorney went to the police station and repeatedly asked to see his client, but was repeatedly refused access, saying that Escobedo did not want to see him. Police and prosecutors proceeded to interrogate Escobedo for fourteen-and-a-half hours and refused his request to speak with his attorney with the same consistency throughout that time. While being interrogated, Escobedo made statements implicating his knowledge of the crime. After conviction for murder, Escobedo appealed on the basis of being denied the right to counsel. Escobedo appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, which initially held the confession inadmissible and reversed the conviction. Illinois petitioned for rehearing and the court then affirmed the conviction. Escobedo appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. ISSUE: WON, under the circumstances, the refusal by the police to honor petitioners request to consult with his lawyer during the course of an interrogation constitutes a denial of the Assistance of Counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment. RULING: YES. When Escobedo requested, and was denied, an opportunity to consult with his lawyer, the investigation had ceased to be a general investigation of an unsolved crime. Escobedo had become the accused, and the purpose of the interrogation was to get him to confess his guilt despite his constitutional right to do so. In such a scenario, with Escobedo requesting and being denied an opportunity to consult with his lawyer, and with the police not having effectively warned him of his absolute constitutional right to remain silent, the Supreme Court ruled that Escobedo has been denied the Assistance of Counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment as made obligatory upon the States by the Fourteenth Amendment (as stated in Gideon v. Wainwright). As such, no statement elicited by the police during the interrogation may be used against him in a criminal trial. NOTE: The above ruling was later implicitly overruled by the landmark case, Miranda v. Arizona. MIRANDA V. ARIZONA 384 U.S. 436, 16 L Ed e2 692, 86 S Ct 1602 (1966) FACTS: Police arrested Miranda and took him to a special interrogation room where they secured a confession. The inculpatory admission was admitted at trial. In the end, Miranda was convicted for kidnapping and rape, a decision affirmed on appeal. ISSUE: WON the privilege set in the Fifth Amendment is fully applicable during a period of custodial investigation. RULING: Due to the coercive nature of the custodial interrogation by police (Mr. Chief Justice Warren cited several police training manuals which had not been provided in the arguments), no confession could be admissible under the Fifth Amendment selfincrimination clause and Sixth Amendment right to an attorney unless a suspect had been made aware of his/her rights and the suspect had then waived them. The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the

lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him. If the individual indicates in any manner, at any time prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease ... If the individual states that he wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease until an attorney is present. At that time, the individual must have an opportunity to confer with the attorney and to have him present during any subsequent questioning. DICKERSON V. UNITED STATES 530 U.S. 428, 152 L Ed 2d 1069, 122 S Ct 2315 (2000) FACTS: In the wake of the ruling on Miranda v. Arizona, Congress enacted a law which in essence makes the admissibility of a suspects statements on a custodial interrogation turn solely on whether they were made voluntarily. Dickerson was indicted for bank robbery, conspiracy to commit bank robbery, and using a firearm in the course of committing a crime of violence. He moved to suppress a statement he had made to the FBI, on the ground that he had not received Miranda warnings before being interrogated. The District Court granted his petition, and the Government took an interlocutory appeal; the Fourth Circuit reversed, acknowledging that even though Dickerson had not received Miranda rights, the law was satisfied because his statement was voluntary concluding that Miranda was not a constitutional holding and that Congress could by statute have the final say on the question of admissibility. ISSUE: WON the Miranda court announced a constitutional rule or merely exercised its supervisory authority to regulate evidence in the absence of congressional direction. HELD: A little backgrounder: in the past, a suspect's confession had always been inadmissible if it had been the result of coercion, or otherwise given involuntarily. This was true in England, and American law inherited that rule from England. However, as time went on, the US Supreme Court recognized that the Fifth Amendment was an independent source of protection for statements made by criminal defendants in the course of police interrogation. Custodial police interrogation by its very nature "isolates and pressures the individual" so that he might eventually be worn down and confess to crimes he did not commit in order to end the ordeal. In Miranda, the Court had adopted the nowfamous four warnings to protect against this particular evil. Congress, in response, enacted 3501. That statute clearly was designed to overrule Miranda because it expressly focused solely on voluntariness of the confession as a touchstone for admissibility. As regards Congress' authority to pass such a law: on the one hand, the Court's power to craft non-constitutional supervisory rules over the federal courts exists only in the absence of a specific statute passed by Congress. But if on the other hand the Miranda rule was constitutional, Congress could not overrule it, because the Court alone is the final arbiter of what the Constitution requires. As evidence of the fact that the Miranda rule was constitutional in nature, the Court pointed out that many of its subsequent decisions applying and limiting the requirement arose in decisions from state courts, over which the Court lacked the power to impose supervisory non-constitutional rules. Furthermore, although the Court had previously invited legislative involvement in the effort to devise prophylactic measures for protecting criminal defendants against overbearing

tactics of the police, it had consistently held that these measures must not take away from the protections Miranda had afforded. In conclusion, the Court held that Miranda announced a constitutional rule that Congress may not supersede legislatively. ADDITIONAL CASE: PEOPLE V. LAUGA 615 SCRA 548 FACTS: Lagua, being the father of AAA with lewd design, with the use of force and intimidation, did then and there, willfully, unlawfully and criminally have carnal knowledge with aforementioned daughter, a 13 year[s]old minor against her will. After the deed was done, AAA recounted what happened with her brother BBB, and then told her grandfather and uncle, and after which they sought the assistance of Moises Boy Banting, a bantay

bayan.

Moises Boy Banting found appellant in his house wearing only his underwear. He invited appellant to the police station, to which appellant obliged. At the police outpost, he admitted to him that he raped AAA because he was unable to control himself said confession being something which he denied in his testimony. The RTC found him guilty and convicted him, and upon appeal said conviction was modified by the CA (by rendering Lagua ineligible for parole and increasing the indemnity and moral damages to be paid), hence this petition. ISSUE: WON his alleged confession with a bantay bayan is admissible in evidence. RULING: NO. This Court is convinced that barangay-based volunteer organizations in the nature of watch groups, as in the case of the "bantay bayan," are recognized by the local government unit to perform functions relating to the preservation of peace and order at the barangay level. Thus, without ruling on the legality of the actions taken by Moises Boy Banting, and the specific scope of duties and responsibilities delegated to a "bantay bayan," particularly on the authority to conduct a custodial investigation, any inquiry he makes has the color of a state-related function and objective insofar as the entitlement of a suspect to his constitutional rights provided for under Article III, Section 12 of the Constitution, otherwise known as the Miranda Rights, is concerned, therefore finding the extrajudicial confession of appellant, which was taken without a counsel, inadmissible in evidence. (This does not change anything either way as Laguas guilt was not deduced solely from said confession but from confluence of evidence showing his guilt beyond reasonable doubt but thats another issue.)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Letter To The BarangayDocumento1 paginaLetter To The BarangayJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- CE133P - C1: Third Floor PlanDocumento1 paginaCE133P - C1: Third Floor PlanJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular DrugsDocumento2 pagineCardiovascular DrugsJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- (Hungary) SWOT AnalysisDocumento2 pagine(Hungary) SWOT AnalysisJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Existent and May Be Wholly Disregarded. Such Judgment: Ancheta, 424 SCRA 725, 735 (2004) Ramos v. CA, 180 SCRADocumento1 paginaExistent and May Be Wholly Disregarded. Such Judgment: Ancheta, 424 SCRA 725, 735 (2004) Ramos v. CA, 180 SCRAJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Civpro Madness Part XDocumento2 pagineCivpro Madness Part XJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurisdiction and Modes of AppealDocumento18 pagineJurisdiction and Modes of AppealJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 04 Remedial Law (SpecPro)Documento13 pagine04 Remedial Law (SpecPro)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Political Law (Wip)Documento42 paginePolitical Law (Wip)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 04 Remedial Law (SpecPro) (Second Revise)Documento25 pagine04 Remedial Law (SpecPro) (Second Revise)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Legal Ethics I. Preliminaries: Practice of LawDocumento12 pagineLegal Ethics I. Preliminaries: Practice of LawJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 Remedial Law (Special Writs)Documento11 pagine05 Remedial Law (Special Writs)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 03 Remedial Law (SCAPR)Documento25 pagine03 Remedial Law (SCAPR)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- 07 Remedial Law (Evid)Documento24 pagine07 Remedial Law (Evid)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Remedial Law (CivPro)Documento21 pagineRemedial Law (CivPro)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Remedial Law: (Notes in Are Opinions of The Lecturer, of Authors On The Subject, or of The Reviewee.)Documento1 paginaRemedial Law: (Notes in Are Opinions of The Lecturer, of Authors On The Subject, or of The Reviewee.)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Lease Lease Is A Contract Whereby One Person (Lessor) Binds Himself To Grant Temporarily The Use of ADocumento1 paginaLease Lease Is A Contract Whereby One Person (Lessor) Binds Himself To Grant Temporarily The Use of AJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Roles of Speakers in Asian Parliamentary FormatDocumento1 paginaRoles of Speakers in Asian Parliamentary FormatJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Obergefell vs. Hodges: 576 U.S. - , June 26, 2015 Kennedy, JDocumento25 pagineObergefell vs. Hodges: 576 U.S. - , June 26, 2015 Kennedy, JJustin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Laude vs. Ginez-Jabalde (MCLE)Documento29 pagineLaude vs. Ginez-Jabalde (MCLE)Justin CebrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Salatan Damsel - Finalexam.crim LawDocumento4 pagineSalatan Damsel - Finalexam.crim LawDamsel G. SalatanNessuna valutazione finora

- PORTFOLIO Opinion Essays ClassDocumento5 paginePORTFOLIO Opinion Essays ClassCalin Chelcea100% (1)

- Criminal Procedure (Finals)Documento28 pagineCriminal Procedure (Finals)JNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Rule On Juveniles in Conflict With The LawDocumento19 pagineSupreme Court Rule On Juveniles in Conflict With The LawCha GalangNessuna valutazione finora

- 1781 SampleDocumento21 pagine1781 SampleDioner RayNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Conduct and Ethics F8800 PDFDocumento63 pagineProfessional Conduct and Ethics F8800 PDFSimushi Simushi100% (4)

- Identity Theft WebquestDocumento2 pagineIdentity Theft Webquestapi-256439506Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ucc-1 Traveling Rights and UnderstandingDocumento8 pagineUcc-1 Traveling Rights and Understanding6262363773100% (28)

- A Detailed Guide On Kerbrute PDFDocumento16 pagineA Detailed Guide On Kerbrute PDFsamNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Bar Questions v. Campanilla's WorkDocumento41 pagine2017 Bar Questions v. Campanilla's WorkKevin100% (3)

- United States v. Robert Singleton, Alias Popeye, Charles William Mosby. Appeal of Charles William Mosby, 439 F.2d 381, 3rd Cir. (1971)Documento10 pagineUnited States v. Robert Singleton, Alias Popeye, Charles William Mosby. Appeal of Charles William Mosby, 439 F.2d 381, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 11 - The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, The Juvenile Justice and Welfare CounciDocumento16 pagineChapter 11 - The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, The Juvenile Justice and Welfare Councikim ryan uchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Liang Vs People of The Philippines GR No. 125865 January 28, 2000Documento18 pagineLiang Vs People of The Philippines GR No. 125865 January 28, 2000Kayee KatNessuna valutazione finora

- Marquez v. DesiertoDocumento12 pagineMarquez v. DesiertoTon RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- Similar Fact EvidenceDocumento3 pagineSimilar Fact EvidenceKaren Christine M. AtongNessuna valutazione finora

- Penal Code Act 574 Section 509Documento1 paginaPenal Code Act 574 Section 509David PalashNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Science IIDocumento4 pagineSocial Science IIArvie Angeles Alferez0% (1)

- En Banc: (G.R. No. 162230. August 12, 2014.)Documento16 pagineEn Banc: (G.R. No. 162230. August 12, 2014.)Mico Maagma CarpioNessuna valutazione finora

- Henry SingletonDocumento11 pagineHenry Singletonapi-260143426Nessuna valutazione finora

- Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs ACT OF 2002: Penal ProvisionsDocumento60 pagineComprehensive Dangerous Drugs ACT OF 2002: Penal ProvisionsFREDELINO E. GOROSPENessuna valutazione finora

- Full Text People Vs CatubayDocumento6 pagineFull Text People Vs CatubayJASON BRIAN AVELINONessuna valutazione finora

- Case of J.M. v. DenmarkDocumento21 pagineCase of J.M. v. DenmarkmrbtdfNessuna valutazione finora

- Troy Issues Updated Most WantedDocumento6 pagineTroy Issues Updated Most WantedMikeGoodwinTUNessuna valutazione finora

- Design and Implementation of A Computerized Case Scheduling System of Court of LawDocumento53 pagineDesign and Implementation of A Computerized Case Scheduling System of Court of LawJoseph Ovie100% (1)

- Quick Notes On Indeterminate Sentence LawDocumento1 paginaQuick Notes On Indeterminate Sentence LawJonas PeridaNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Ohio ST JCrim L407Documento21 pagine5 Ohio ST JCrim L407shivansh nangiaNessuna valutazione finora

- AB-2043 - Suggestions For Fugitive Recovery Laws Moving ForwardDocumento2 pagineAB-2043 - Suggestions For Fugitive Recovery Laws Moving ForwardDan EscamillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim 1 Art 100 - 113 ReviewerDocumento9 pagineCrim 1 Art 100 - 113 ReviewerEcnerolAicnelavNessuna valutazione finora

- Genet, Actor and MartyrDocumento636 pagineGenet, Actor and MartyrFrancisco Solís100% (1)

- Supreme Court Case Analysis-Team ProjectDocumento5 pagineSupreme Court Case Analysis-Team ProjectJasmineA.RomeroNessuna valutazione finora