Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Community Analysis Methodology Evaluation

Caricato da

tevenstaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Community Analysis Methodology Evaluation

Caricato da

tevenstaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Thea Evenstad LI811 Emporia State University SLIM 11/19/11

Content Analysis: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Research Design

Content analysis is a research methodology that may be used in many research contexts. Libraries may use content analysis as one methodology for collecting and analyzing data for a community needs analysis. Beck and Manuel define content analysis as procedures for defining, measuring, and analyzing both the substance and meaning of texts or messages or documents (2008, p. 35). Krippendorff similarly defines content analysis as a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (1980, p. 18). These definitions are both broader in scope than Neuendorfs more limited definition of content analysis as the systematic, objective, quantitative analysis of messages (2002, p. 1). For the purposes of this investigation, Krippendorffs definition is most apt as it particularly addresses content analysis as a research technique and is broad enough to account for many different types of studies. For example, despite Neuendorfs assertions to the contrary, most researchers contend that content analysis may be either quantitative or qualitative (Beck & Manuel, 2008; White and Marsh, 2006). In content analysis, texts constitute the population to be studied. The content analysis consists of the systematic procedures by which texts are analyzed. The results from a content analysis must be valid and replicable. Findings from a content analysis study bring together data from many texts and serve to highlight trends or themes of significance discovered during the analysis.

Evenstad 2 Advantages Content analysis is a method that provides the opportunity to analyze several variables within a large set of literature and provides trustworthy data to describe that literature (Julien, Pecoskie, & Reed, 2011). This method of investigation has many advantages over other methodologies like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. One advantage is the replicability of a content analysis (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 18). Theoretically, if a researcher wanted to replicate a content analysis, he or she could use the same texts and the same content analysis procedure and produce the same results. A similar advantage is that content analysis is nonreactive (Beck & Manuel, 2008). Since the target population is comprised of unchanging texts, it will not react to the researcher in the way that a person being interviewed might. Additionally, content analysis is an unobtrusive research methodology (Krippendorff, 1980; Beck & Manuel, 2008). For this reason, content analyses are not subject to the same rigorous review that research involving human subjects entails. Content analysis can treat unstructured material as data (Krippendorff, 1980). This characteristic is especially helpful for studying data generated over a long period of timethe study does not have to have planned data collection long ago to have data from a previous time period. This highlights another advantage: content analysis is not limited by time or space (Beck & Manuel, 1980). Data can come from many different geographic areas without requiring researchers to travel, and cover a long span of time without requiring prior planning.

Disadvantages There are disadvantages to content analysis, however. This research method is often timeconsuming and labor intensive (Beck & Manuel, 2008). Neuendorf asserts that content analyses require training and substantial planning to be successful (Neuendorf, 2002, p. 8). Coding

Evenstad 3 information is time-consuming whether it is accomplished with human coders, who require training and reliability testing, or computer coding, which requires effort to program and to select dictionaries that will work effectively. Coding reliability poses another concern. Krippendorff argues that content analysts, Must work to ensure the consistent application of analytical procedures and standards (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 88). Stemler specifies two problems during coding that can affect the validity of a content analysis: faulty definitions of categories and nonmutually exclusive and exhaustive categories (2001, conclusion). Another disadvantage of this methodology is that unlike interviews or focus groups, content analysis cannot ask questions about motives. Content analysts cannot learn about causes behind the creation of texts nor the effects that texts might have; content analysis can only demonstrate themes or trends (Beck and Manuel, 2008). Additionally, content analysis cannot determine the accuracy of a text or interpret the significance of content (Beck & Manuel, 2008). Finally, while content analyses do not have to contend with a population that reacts to the research being conducted, Krippendorff indicates that, Although content analysts are not bound to analyze their data with reference to the conceptions or intended audiences of their texts authors, they must at least consider that texts may have been intended for someone like them (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 31). A text has an intended audience and the author may be aware that his or her text may be studied one day and create it accordingly.

How to Analyze and Use the Data The ultimate goal of the content analyst is to infer answers to particular research questions from their texts (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 25). Beck and Manual (2008) indicate that like every methodology, a content analysis study consists of six steps: 1) formulating questions, 2) defining

Evenstad 4 the population, 3) selecting a research design, 4) gathering data, 5) interpreting the evidence, and 6) telling the story. There are many components of a content analysis that fit within this larger scheme. A researcher must decide on units of data, generate a sampling plan and create a representative sample, develop coding instructions and a coding plan that includes reliability testing, reduce the data through statistical or other simplifying functions, draw inferences, and narrate research findings (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 86). While each of these parts is important, astute coding is fundamental to the success of a content analysis. Beck and Manuel assert that Without solid, well-though-out descriptions of categories and carefully devised coding procedures, content analysis is weak [ . . . ] Content analysts either rely on standard definitions or create their own definitions for categories [ . . . ] It is essential that the categories be exhaustive and mutually exclusive (2008, p. 46). The research design must consider how coding is conducted and how the data will be analyzed. Magi (2010) thoroughly details this process, from research topic to target population, to sample, to data collection and analysis. Her data collection process included development of the codebook, coder training and codebook refinement, pilot coding, and final coding. Reliability was assessed during both pilot and final coding. Through a thorough and well-designed content analysis, Magi found that the privacy policies of major vendors of online library resources fail to express a commitment to many of the standards articulated by the librarian profession and information technology industry for the handling and protection of user information (2010). Her conclusion certainly has important implications for LIS. Her study also highlights how analysis is unique for each study and depends on the data that will be analyzed. Ultimately, content analysis allows inferences to be made which can then be corroborated using other methods of data collection (Stemler, 2001, para. 2). Content analysis is a welcome tool for community needs analysis.

Evenstad 5 Sample Instrument: Sample Codebook Community Needs Analysis Unit of data collection: Each official student publication printed between 2000 and 2010. Document number: Fill in the document number as listed on the label on your document. Coder name: Fill in your name Date: Todays date Publication category: Indicate the category based on the title; if that isnt possible, base it on the content of the publication. 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Student newspaper Student arts journal Student political opinion journal Student group brochure Other official student publication

Year: List the year the document was published. If unknown, enter 0000. Student groups: How many references to official student groups are made in this document (The list of official student groups recognized by the Associated Students of the University can be found in the appendix). 1) 0 2) 1-2 3) 3-4 4) 5-6 5) 6 or more Author level of education: What level of education have the authors attained? Select all that apply. 1) Freshman 2) Sophomore 3) Junior 4) Senior 5) Graduate student Article topics: Assign articles/information in the publication to these categories. Select all that apply. 1) Arts and music 5) Politics 2) Science and technology 6) Outdoor activities 3) Sports 7) Lectures and university4) Activism/charitable work sponsored events

Evenstad 6 References

Beck, S. E. & Manuel, K. (2008). Practical research methods for librarians and information professionals. New York, NY: Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc. Julien, H., Pecoskie, J. & Reed, K. (2011). Trends in information behavior research, 1999-2008: A content analysis. Library and Information Science Research 33, 19-24. Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Magi, T. J. (2010). A content analysis of library vendor privacy policies: Do they meet our standards? College & Research Libraries 71(3), 254-272. Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(17). Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=17. White, M. D. & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends 55(1), 22-45.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Teaching PresentationDocumento16 pagineTeaching PresentationtevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Library Strategic PlanDocumento38 paginePublic Library Strategic PlantevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Instruction PlanDocumento11 pagineInstruction Plantevensta100% (1)

- Research-Based Action PlanDocumento14 pagineResearch-Based Action PlantevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- VOIP Reference ServicesDocumento12 pagineVOIP Reference ServicestevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Media Best PracticesDocumento10 pagineSocial Media Best PracticestevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Annotated BibliographyDocumento6 pagineAnnotated BibliographytevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective JournalDocumento22 pagineReflective JournaltevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Library Strategic PlanDocumento38 paginePublic Library Strategic PlantevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dictionary Organizes Entries Alphabetically by The Key Term in English, and Includes TheDocumento6 pagineDictionary Organizes Entries Alphabetically by The Key Term in English, and Includes ThetevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Collection EvaluationDocumento14 pagineCollection EvaluationtevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Information Seeker InterviewDocumento7 pagineInformation Seeker InterviewtevenstaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- 2022 EDUC8 MODULE 1 IntroductionDocumento14 pagine2022 EDUC8 MODULE 1 IntroductionAmelia Bragais RemallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Maths Worksheets 5Documento4 pagineMaths Worksheets 5SandyaNessuna valutazione finora

- DiassDocumento33 pagineDiassOlive AsuncionNessuna valutazione finora

- Dinesh Publications Private LimitedDocumento18 pagineDinesh Publications Private LimitedNitin Kumar0% (1)

- CM 9Documento10 pagineCM 9Nelaner BantilingNessuna valutazione finora

- North Jersey Jewish Standard, July 24, 2015Documento44 pagineNorth Jersey Jewish Standard, July 24, 2015New Jersey Jewish StandardNessuna valutazione finora

- Mariasole Bianco CV 0914 WebsiteDocumento3 pagineMariasole Bianco CV 0914 Websiteapi-246873479Nessuna valutazione finora

- Detailed Lesson Plan in ArtsDocumento5 pagineDetailed Lesson Plan in ArtsNiño Ronelle Mateo Eligino83% (70)

- International Perspectives On Educational PsychologyDocumento4 pagineInternational Perspectives On Educational PsychologyCierre WesleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Characterizing The Parent Role in School-Based Interventions For Autism: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocumento14 pagineCharacterizing The Parent Role in School-Based Interventions For Autism: A Systematic Literature Reviewgabyliz52Nessuna valutazione finora

- TPGP - January 2021 Educ 556Documento4 pagineTPGP - January 2021 Educ 556api-537676118100% (1)

- Lesson Plan in English 6 - Cot 1 2021-2022Documento3 pagineLesson Plan in English 6 - Cot 1 2021-2022Sheila Atanacio Indico100% (2)

- Letter of Approval To Conduct ResearchDocumento3 pagineLetter of Approval To Conduct ResearchANGEL ALMOGUERRANessuna valutazione finora

- Detroit Cathedral Program Final 4-17-12Documento2 pagineDetroit Cathedral Program Final 4-17-12Darryl BradleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Indiana Secondary Transition Resource CenterDocumento1 paginaIndiana Secondary Transition Resource CenterIndiana Family to FamilyNessuna valutazione finora

- AP Social Welfare Application FormDocumento2 pagineAP Social Welfare Application FormMadhu AbhishekNessuna valutazione finora

- Parent and Family Involvement Plan 1Documento29 pagineParent and Family Involvement Plan 1api-248637452Nessuna valutazione finora

- Camping Trip Story English LanguageDocumento3 pagineCamping Trip Story English LanguageJihad farhadNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Guide For Critical Approaches in Teaching Philippine LiteratureDocumento7 pagineTeaching Guide For Critical Approaches in Teaching Philippine LiteratureMaria Zarah MenesesNessuna valutazione finora

- Singhania University PHD Course Work ScheduleDocumento6 pagineSinghania University PHD Course Work Schedulejyw0zafiwim3100% (2)

- Psychology BrochureDocumento12 paginePsychology BrochuretanasedanielaNessuna valutazione finora

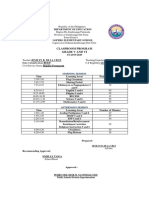

- Classroom Program JenDocumento1 paginaClassroom Program JenjenilynNessuna valutazione finora

- Total Quality Management & Six SigmaDocumento10 pagineTotal Quality Management & Six SigmaJohn SamonteNessuna valutazione finora

- Lac Table of SpecificationsDocumento7 pagineLac Table of SpecificationsMarites EstepaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cyber Security Program (Postgraduate) T433 - George Brown CollegeDocumento7 pagineCyber Security Program (Postgraduate) T433 - George Brown CollegeAdil AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Learning SoftwareDocumento7 pagineE-Learning SoftwareGoodman HereNessuna valutazione finora

- Business English Practice PDFDocumento3 pagineBusiness English Practice PDFMutiara FaradinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Amit CVDocumento3 pagineAmit CVchandramallikachakrabortyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab Record Front PageDocumento6 pagineLab Record Front PageHari Suriya 520Nessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Nursing PresentationDocumento39 pagineContemporary Nursing Presentationapi-443501911Nessuna valutazione finora