Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Oxford University Press Social Work: This Content Downloaded From 192.188.53.214 On Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

Caricato da

BetteDavisEyes00Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Oxford University Press Social Work: This Content Downloaded From 192.188.53.214 On Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

Caricato da

BetteDavisEyes00Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Mediation: Conjoint Problem Solving

Author(s): Susan Meyers Chandler

Source: Social Work, Vol. 30, No. 4 (JulyAugust 1985), pp. 346-349

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23714503

Accessed: 20-06-2016 22:50 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social

Work

This content downloaded from 192.188.53.214 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Mediation:

Conjoint Problem Solving

SINCE

THE MID-1850s,

with the

development

and institution

of

Susan Meyers Chandler

the Settlement House Movement, the

social work profession has tried to

identify and meet the needs of the

communities it serves.1 Social work

has been active in identifying injus

tices inflicted on the poor, the elderly,

children, immigrants, and more re

cently, racial minorities and women.

Exposing and analyzing injustice is

inherent to the profession.2 Rectifying

injustice is another matter. Although

the profession espouses the need for

social change to ameliorate social in

justice, it has been more successful

in helping victims through the pro

vision of concrete assistance, educa

tion, and counseling. This situation

exists in part because there are nu

Mediation is a technique of

joint advocacy that is being

successfully applied on a

growing scale to resolve inter

personal conflicts. Its appli

cation has great relevance to

the practice of social work.

The author describes the me

diation process, outlines its

functions, and compares it

with traditional social work

methods.

merous barriers to achieving social

change and social justice. Moreover,

social workers are aware that for

most people access to justice is lim

ited and complicated and that justice

result is that most disputants either

per se is not necessarily a practical

means for resolving everyday conflicts.

endure continuing conflict or, if pos

predicting that over 40 percent of the

marriages of women in their twenties

friends, and if these conflicts remain

For example, demographers are

will end in divorce.3 The vast majori

ty of contested divorces are handled

solely by attorneys in the traditional

adversarial legal system, with social

workers playing almost no role. Thus,

the emotionally charged issues of child

custody, visitation arrangements,

child support, rehabilitative alimony,

property divisions, and other concerns

are left up to the courts. Social work

ers then may help individuals adjust

and adapt to whatever "justice" has

been decided for them.

In many types of interpersonal dis

putes, the issues of justice are so

complex and personal that an out

sider with limited time and resources,

such as a court, is unable to meet

both the legal and psychological

needs of the participants. Often the

sible, avoid contact. Yet many con

flicts involve family members or

unresolved they fester and may even

tually erode an important source of

social support.

Because of the cost, delay, and un

satisfactory quality of the formal

conflict-resolving mechanism in our

society, efforts to develop different

types of conflict resolution programs

have been attempted since the mid

1970s. In over 200 locations, pro

grams have been established to bring

citizens a legitimate, free, speedy, in

formal, and effective means to resolve

mediation will likely become more

prominent because it is applicable to

many areas of social work practice.

WHAT IS MEDIATION?

Mediation is a resource for handling

conflict between people by providing

a neutral forum in which disputants

are encouraged to find a mutually

satisfactory resolution to their prob

lems.4 The mediator is a neutral third

party who listens to disputants de

scribe their concerns and helps both

sides to talk about their feelings. The

mediator works to facilitate open and

accurate communication between dis

putants and encourages them to de

velop a practical compromise or new

alternatives that can lead to a solu

tion. Mediation does not attempt to

make diagnostic assessments about

the underlying causes or factors pre

cipitating the problem. The mediator

does not function as a therapist

through communications that are de

signed to contribute to or encourage

reflective consideration. Nor does the

mediator focus on the psychological

patterns and personality dynamics of

the disputants themselves. Mediators

refrain from judging or allowing their

own values to intrude into the process.

Mediation has proved successful

with a wide variety of people. Media

tion helps to resolve disagreements

among family members and other

domestic problems. It can serve as a

process to clarify predivorce issues

and has been used extensively in

child custody cases. Mediation has

been successful in resolving disputes

interpersonal problems. This form of

between students and teachers, teach

ers and school staff, and schools and

mediation, and it both resembles and

differs from traditional social work

parents (especially in cases of main

streaming disabled children).5 And

mediation projects have been estab

conflict resolution is often called

practice. For social workers, it can be

conceptualized as a form of conjoint

problem solving. Although it is not

now taught in schools of social work.

lished across the nation to handle

neighborhood disputes, landlord-ten

ant conflicts, and consumer-merchant

346 CCC Code: 0037-8046/85 $1.00 1985, National Association of Social Workers, Inc.

This content downloaded from 192.188.53.214 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

disputes. During the last five years, { 2. Mediation is most effective when

more than 30 states have developed _ both parties are willing to express

projects using mediation as the pri- The Tned.ia.tOT does personal wants and needs. Although

mary intervention mode. Although not enoaae in public attitudes are changing, there

the goals of these projects are dis- , y is still some stigma associated with

parate, they all tend to focus pri- diagnostic activities. taking problems to a public institu

marily on interpersonal disputes __ tion, which prevents many people

among people who have an ongoing " from receiving help with their family

relationship. Research has shown and interpersonal problems. Public

that such disputants are the most plored. Then the mediator begins to attitudes may also prevent some peo

amenable to negotiation and possible develop a design or specific plan of pie from going into therapy or see

compromise because the interests of action and asks the disputants to be- ing a counselor and may deter others

both parties are served by a joint come active in this process. from taking responsibility for the

settlement.6 Problem-Solving Phase. Using a ongoing problem. The rise of new

A two-year study conducted by number of procedures, such as joint community-based problem-solving

Roehl and Cook found that mediation meetings, private caucuses, and shut- programs incorporating mediation pro

is an effective and satisfactory method tie diplomacy, the mediator works cedures and conducted by community

for resolving many types of minor with all parties to define the poten- volunteer mediators may strengthen

interpersonal disputes.7 That study tial solutions to the problem. Using and empower community residents

reviewed more than 4,000 cases han- either negotiation, creative problem by enhancing their ability to handle

died through mediation and found solving, or both, the mediator helps problems on their own.12 Mediation

that 82 percent of these cases con- the parties come to specific agree- may well provide a valuable mecha

cluded with a successful resolution ments. These are written solutions nism for allowing people to commu

and agreement. Forty-five percent of that the disputants developed them- nicate with each other, breaking down

the disputes involved family mem- selves. hostilities founded on misunderstand

bers or relatives. Other research has The mediator facilitates communi- ings. For many people who would

also documented high rates of sue- cation and oversees the process, but have otherwise just endured a prob

cess with mediation.8 the determination of content remains lem or avoided dealing with it, media

with the disputants. The role of the tion may provide a stress-reducing

mediator is to conduct joint advocacy structure for conflict resolution that

THE PROCESS

and create a climate of agreement in meets personal needs.

Mediation has been defined by Witty which the parties ready themselves 3. The mediation process stresses

as the "facilitation of an agreement to negotiate a solution to the conflict, mutual agreements in which both

between two or more disputing par- The elements of an agreement be- sides win. Unlike the adjudicative

ties by an agreed upon third party."9 come the building blocks for a re- system with its complex rules of pro

Each party agrees to utilize the ser- alignment of an individual's sense of cedure, mediation is an integrative

vices of a mediator, but the outcome belonging to a family, group, or com- and conciliatory process with a o

is an agreement made by the dis- munity. judgmental convenor who works to

putants themselves. Successful medi- emphasize the bonds between the

at ions, though they may vary in DDTXjTDT M __T *Tmiu participants and encourages broad

many respects from one another, "K1urL1! ur MLU1A1 lum discussion of the issues so that all

move through three phases.10 The process just described is based viewpoints are expressed. A con

FOrum Phase. The mediator begins on several principles that have proved flict-resolving system for persons in

with an exploration of the issues and important to the successful imple- terested in maintaining and enhanc

gauges the appropriateness of the mentation of mediation as a conflict- ing their relationship may also func

conflict for mediation. If mediation is resolution technique. tion to prevent future conflict, stress,

appropriate, the mediator explains 1. Mediation seems to be most sue- and disputes.

the process and secures an agree- cessful when there is some ongoing 4. Mediation is believed to be most

ment for his or her involvement from personal connection or personal in- successful when there is a relatively

the participants. The mediator then teraction between the disputants, egalitarian relationship between the

begins the information-gathering ac- Because the process is voluntary and disputants. In practice, this principle

tivities, which include both face-to- noncoercive, disputants who come to has not been validated. Witty has

face interactions with all parties or mediation must be willing to discuss found, however, that mediation itself

individuals and confidential caucuses their concerns. Many who come to functions to equalize status differ

with one party at a time. mediation have experienced frustra- entials (if only in a specific and local

Strategic-Planning Phase. The me- tion, stress, fear, and disillusionment context). She argues that people of

diator examines all the information with the judicial system or social ser- vastly different income and status

gathered, reviews the history of the vice agencies, which have been un- can successfully mediate because the

conflict, and assesses the issues, po- able to provide meaningful and last- agreement to enter the process em

sitions, and interests involved. During ing resolutions to their problems, powers each side.13

this analytic stage, the mediator may Several studies have demonstrated 5. People are more likely to adhere

reconvene the parties if some issues that mediation is extremely satisfy- to agreements they understand and

remain unclear or the mediator feels ing to the participants and that it have an integral part in making than

that an issue has not been fully ex- significantly reduces tensions.11 to agreements that are externally im

Chandler / Mediation: Conjoint Problem Solving 347

This content downloaded from 192.188.53.214 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

posed. The mediation process docu-

ments the areas of agreement between _ _ _. ,. . . ,. , , , ,

the parties. The agreement is written Mediation IS D6llCUCu tO D6 TTLOSt

in

participants own words and accu successful when there is a relatively

rately states the items they have ** # # , ^

agreed to. Because the responsibility egalitarian relationship between the disputants.

for the agreement is focused on the

participants, they are motivated to H

adhere to the elements of it. And

because both sides have "won," there work, the control of the process rests that it remain confidential. A media

is a high likelihood of compliance. primarily with the worker; in media- tor may encourage one side to tell the

6. Mediation is a process of joint tion, after ground rules are estab- other but will not divulge confidential

advocacy, which empowers people fished, the control of the content rests information among disputants. While

and enhances their sense of dignity solely with the disputants. social workers also attempt to respect

and self-worth while preserving the Compton and Galloway suggest the wishes of their clients and not

responsible aspects of self-determi- that problem solving itself is a pro- divulge case information outside of

nation. cess by which the social worker and the treatment setting, in many cases

the client decide what the problem is a social worker will want or be obli

SOCIAL WORK AND they wish to address, what the out- gated to share diagnostic information

MFniATTfiN come is to be, how to conceptualize with other family members or agency

it, and what specific procedures and persons. For example, social workers

Many activities referred to as media- actions will be needed to meet the cannot guarantee confidentially to an

tion might seem indistinguishable objectives.16 This approach supports adolescent client, because there are

from social work. However, there are the client's right to his or her per- established obligations to the child's

differences in emphasis, philosophy, sonal definition of the problem and family, clinic, agency, and community,

technique, and outcome that can be requires that some negotiation take In many instances, the therapist may

usefully compared. Mediation always place if the worker and the client see the holding of secrets as non

involves the participation of both par- have not agreed on what they will therapeutic. Mediators, on the other

ties in a conflict. It is oriented toward undertake together. This element of hand, are not bound to other family

the resolution of specific issues and the problem-solving framework differs members or agency requirements

designed as a short-term process, from the mediation process because and can ensure confidentiality.

Typically, issues of justice and fair- the participants in mediation select The goal-identification stage of the

ness are paramount in the discus- and structure the problems or issues social work process is similar to the

sions, and remedies are closely re- to be discussed and the mediator strategic-planning phase in mediation,

lated to the rights that each side ac- only reinforces their "ownership" of Both attempt to summarize feelings

cords the other. In mediation, conflict the problem. and shift to a long-range orientation,

is viewed not as something negative Several specific elements of the The social worker attends to the cli

but as a legitimate vehicle for per- social work problem-solving model ent's wants and suggested solutions

sonal and social change. The respon- can be identified and contrasted to and also examines the forms of as

sibility for the outcome of the process the phases in the mediation process, sistance being sought and the re

always rests with the parties them- The problem identification and defi- sources available. In mediation, the

selves. nition stages, in which background mediator consistently directs the re

Social workers are skilled practition- issues and details of the problem are quests for assistance back to the par

re in relating to and communicating delineated, are similar. An initial dis- ticipants and helps them examine

with others. They assist other people cussion of the problem begins at the their own ability to generate resources,

(clients or disputants) in moving for- opening phase of mediation and dur- The social worker assesses the cli

ward and facilitate the problem-solv- ing the contract phase in the social ent's motivation, coping capacities,

ing capacities of others. A major work process. In mediation, confiden- family and social support systems,

theoretical distinction between a tial concerns, fears, and feelings are socioeconomic situation, personality

social worker's approach and the pro- encouraged during a private caucus adaptation, and developmental capac

cess of mediation lies in the practi- with one disputant at a time. In the ities. The mediator does not engage

tioner's responsibility. Perlman em- social work process, this may occur in diagnostic activities and would

phasizes the social worker's role in as the worker attempts to assess the refer cases in which the participants

thinking about "the facta" assessing precipitating factors surrounding the were unable to continue owing to

the clients and the situation, diagnos- client's concerns and evaluate which psychological incapacities elsewhere,

ing the problems, and planning for are the most critical areas to address. Social workers see advocacy as a pro

the best solutions.14 She places the While both processes may allow in- fessional responsibility and follow up

primary responsibility for the "head sight into the persons and the prob- on cases to see that needs have been

work" on the social work profession- lem during this stage, a major differ- met. Mediators do not follow the case

al, whereas others see the problem- ence arises in terms of confidentiality, to that extent and usually terminate

solving work, including the assess- A mediator establishes ground rules contact after the agreements are

ment and decision-making activities, of confidentiality in the first phase of signed.

as a responsibility shared between the mediation and will not work with An obvious difference between so

the client and the worker.15 In social the material if it has been requested cial work and mediation is the num

348

Social

Work

July-August

This content downloaded from 192.188.53.214 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

1985

ber of clients typically seen. Social

workers usually see only one person

at a time as a client and assess his

or her actions in and interactions

with the environment. Even in family

interventions, the family is seen as a

unit functioning both internally and

in interaction with the environment.

Mediators, on the other hand, must

have at least two persons willing to

begin the process because the focus

is interpersonal, not intrapersonal.

TEACHING MEDIATION TO

SOCIAL WORKERS

Training programs for mediators have

developed rapidly across the country.

Mediators usually receive 40 hours of

basic training that includes theories

of conflict resolution, active listen

ing exercises, simulations in which

trainees play both disputants and

mediators, negotiation exercises and

consensus, and experiential learning.

Mediators are taught to be nonjudg

mental and are reminded frequently

that the mediation process is to

enable the disputants to come to

their own conclusions and their own

agreements about the solutions best

for them.

Social workers could easily utilize

the skills of mediation in their prac

tice. Aligned with social work values

is the concept that within the media

tion process itself, people see and

perhaps learn that social control can

be internally created rather than ex

ternally imposed. Communication is

maximized, differences aired, and a

safe and neutral ground for bargain

ing and problem solving is provided.

The concept of taking responsibility

becomes behaviorally concrete. As

the practice of mediation grows and

encompasses more communities and

more problem areas, social workers

should examine this process and de

termine whether its techniques can

be useful to their work, and if so, in

what settings and for what types of

clients.

S usan Meyers Chandler, DSW, is

Associate Professor, School of

Social Work, University of Hawaii,

Honolulu.

can Response to Need (New York: Harper

and Row, 1982).

The

2. See NASW Ad Hoc Committee on

Advocacy, "The Social Worker as Advo

cate: Champion of Social Victims," Social

Work, 14 (April 1969), pp. 16-22; and Ann

Country Place

Power and Change (Washington, D.C.:

State Licensed

Weick and Susan Vandiver, eds Women,

NASW, 1982).

3. Paul Glich and Arthur Norton,

"Marrying, Divorcing and Living Together

in the United States Today," Population

Bulletin, 32, No. 5 (October 1977).

4. David B. Chandler, Community

Mediation in a University Context "Work

ing Paper Series" (Berkeley, Calif.: Institute

for the Study of Social Change, University

of California, 1982.)

5. Claire B. Gallant, Mediation in

Special Education Disputes (Washington,

D.C.: NASW, 1982).

6. See Daniel McGillis, "Minor Dispute

Processing: A Review of Recent Develop

... is a residential treatment

Feeley, eds., Neighborhood Justice:

Assessment of an Emerging Idea (New

extended care, and located on

ments," in Roman Tomasic and Malcolm

facility of 20 years, offering

York: Longman Press, 1982), pp. 60-76.

7. Janice Roehl and Roger Cook, "The

Neighborhood Justice Centers Field Test,"

in Tomasic and Feeley, Neighborhood

a 70-acre estate in the foothills

8. Jessica Pearson and Nancy Thoen

. . . offers a therapeutic com

munity for disturbed young

of the Berkshires;

Justice, pp. 91-110.

nes, "Mediation and Divorce: The Benefits

Outweigh the Costs," Family Advocate 4

(Fall-Winter 1982), pp. 26-32; Pearson,

"How Child Custody Mediation Works in

Practice," Judges Journal, 20 (Winter 1981);

John Benoit, "What Makes a Successful

adults, 18 and older, with

emotional problems, including

substance abuse and eating

Mediation Service," paper presented to the

20th Annual Meeting of the Law and So

ciety Association. Boston, Massachusetts,

June, 1984, unpublished; and Richard

disorders;

Civil Rights Litigation," in C. F. Pinkele

psychiatry with individual,

tice and Democracy (Ames: Iowa State

University Press, 1985).

9. Cathie Witty, Mediation and Soci

ety: Conflict Management in Lebanon

(New York: Academic Press, 1980).

group and family therapy,

enriched by many adjunctive

modalities and emphasizing

work therapy;

Salem, "Mediation as an Alternative to

and W. C. Louthan, eds., Discretion, Jus

. . . integrates traditional

10. See Adler and Chandler, "Mediation

and Alternative Dispute Resolution."

11. See, for example, R. Danzig and

M. J. Lowy, "Everyday Disputes and

Mediation in the United States," Law and

Society, 9 (1975), pp. 675-694.

12. See Paul Wahrhaftig, "An Overview

of Community-oriented Citizen Dispute

Resolution Programs in the Unites States,"

in Richard Abel, ed., Informal Justice:

The Politics of the American Experience

. . . prepares residents for in

dependent living, be it high

school completion, college,

preparation for a career or

vocation.

(New York: Academic Press, 1981).

The

13. Witty, Mediation and Society.

14. Helen Harris Pearlman, Social Case

work: A Problem Solving Process (Chi

cago: University of Chicago Press, 1957).

15. Beulah Compton and Burt Galaway,

Country Place

Box 668

Litchfield Connecticut 06759

Social Work Processes (Homewood, 111.:

Notes and References

Dorsey Press, 1979).

1. See June Axinn and Herman Levin,

Social Welfare: The History of the Ameri

16. Ibid.

Accepted December 22, 1983

(203) 567-8763

Third Party reimbursement

accepted

Chandler / Mediation: Conjoint Problem Solving 349

This content downloaded from 192.188.53.214 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 22:50:16 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Emerging Markets Economics Daily: Latin AmericaDocumento7 pagineEmerging Markets Economics Daily: Latin AmericaBetteDavisEyes00Nessuna valutazione finora

- In Pari Delicto and Ex Turpi CausaDocumento11 pagineIn Pari Delicto and Ex Turpi CausaBetteDavisEyes00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spanish Fisher HandbookDocumento17 pagineSpanish Fisher HandbookBetteDavisEyes00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 9: Communism and Postcommunism - Essentials of Comparative Politics, 4e: W. W. Norton StudySpaceDocumento3 pagineChapter 9: Communism and Postcommunism - Essentials of Comparative Politics, 4e: W. W. Norton StudySpaceBetteDavisEyes00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Case ThomasDocumento3 pagineCase ThomasAriela OktafiraNessuna valutazione finora

- UPS 04 (BI) - Application For Appointment On Contract Basis For Academic StaffDocumento6 pagineUPS 04 (BI) - Application For Appointment On Contract Basis For Academic Staffkhairul danialNessuna valutazione finora

- BCA Communication Skills Project by BILAL AHMED SHAIKDocumento41 pagineBCA Communication Skills Project by BILAL AHMED SHAIKShaik Bilal AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- CTE Microproject Group 1Documento13 pagineCTE Microproject Group 1Amraja DaigavaneNessuna valutazione finora

- DLL Social ScienceDocumento15 pagineDLL Social ScienceMark Andris GempisawNessuna valutazione finora

- Employees Motivation - A Key For The Success of Fast Food RestaurantsDocumento64 pagineEmployees Motivation - A Key For The Success of Fast Food RestaurantsRana ShakoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Higher EducationDocumento19 pagineHigher EducationAnonymous pxy22mwps5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eng 111 Compare ContrastDocumento5 pagineEng 111 Compare Contrastapi-303031111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Research DesignsDocumento5 pagineBasic Research DesignsKaia LouisNessuna valutazione finora

- Chitra NakshatraDocumento12 pagineChitra NakshatraSri KayNessuna valutazione finora

- O Levels Maths Intro BookDocumento2 pagineO Levels Maths Intro BookEngnrXaifQureshi0% (1)

- Saveetha EngineeringDocumento3 pagineSaveetha Engineeringshanjuneo17Nessuna valutazione finora

- Metadata of The Chapter That Will Be Visualized Online: TantaleánDocumento9 pagineMetadata of The Chapter That Will Be Visualized Online: TantaleánHenry TantaleánNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Text of The Official Result of The April 2014 Librarian Licensure ExaminationDocumento2 pagineFull Text of The Official Result of The April 2014 Librarian Licensure ExaminationnasenagunNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychology Research Paper AppendixDocumento6 paginePsychology Research Paper Appendixzrpcnkrif100% (1)

- Mathematics1 Hiligaynon Daily Lesson Log Q1W1Documento5 pagineMathematics1 Hiligaynon Daily Lesson Log Q1W1Maria Theresa VillaruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Universities Institutions That Accept Electronic Scores StedDocumento52 pagineUniversities Institutions That Accept Electronic Scores StedPallepatiShirishRao100% (1)

- Digital Logic and Computer Organization: Unit-I Page NoDocumento4 pagineDigital Logic and Computer Organization: Unit-I Page NoJit AggNessuna valutazione finora

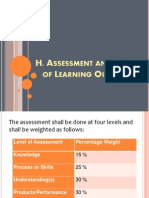

- Assessment and Rating of Learning OutcomesDocumento28 pagineAssessment and Rating of Learning OutcomesElisa Siatres Marcelino100% (1)

- School Nursing SyllabusDocumento4 pagineSchool Nursing SyllabusFirenze Fil100% (1)

- Course Plan - ME 639Documento2 pagineCourse Plan - ME 639Satya SuryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Research On Customer SatisfactionDocumento30 pagineResearch On Customer SatisfactionDona Mae BayoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Top 25 Test-Taking Tips, Suggestions & Strategies: WrongDocumento5 pagineTop 25 Test-Taking Tips, Suggestions & Strategies: WronglheanzNessuna valutazione finora

- EF3e Adv Quicktest 05 OverlayDocumento1 paginaEF3e Adv Quicktest 05 OverlayАрина АхметжановаNessuna valutazione finora

- Disorder of Adult PersonalityDocumento71 pagineDisorder of Adult Personalitychindy layNessuna valutazione finora

- PhiloDocumento4 paginePhiloJewil MeighNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Appendix Freud's Use of The Concept of Regression, Appendix A To Project For A Scientific PsychologyDocumento2 pagineProject Appendix Freud's Use of The Concept of Regression, Appendix A To Project For A Scientific PsychologybrthstNessuna valutazione finora

- Dementia Tri-Fold BrochureDocumento2 pagineDementia Tri-Fold Brochureapi-27331006975% (4)

- 070 - Searching For Effective Neural Network Architectures For Heart Murmur Detection From PhonocardiogramDocumento4 pagine070 - Searching For Effective Neural Network Architectures For Heart Murmur Detection From PhonocardiogramDalana PasinduNessuna valutazione finora

- Nav BR LP Pre b08 1 GRDocumento2 pagineNav BR LP Pre b08 1 GRJessy FarroñayNessuna valutazione finora