Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

4 (Not Pressed)

Caricato da

JDCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

4 (Not Pressed)

Caricato da

JDCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1.

Understand the demand for and

supply of credit. (p. 4-3)

Explain the credit risk analysis

process. (p. 4-7)

Perform a credit analysis, and compute and

interpret measures of credit risk. (p. 4-8)

4.

Describe the credit rating process and

explain why companies are interested

in their credit ratings. (p. 4-23)

5.

Explain bankruptcy prediction models,

and compute and interpret measures

of bankruptcy risk. (p. 4-28)

L E

Credit Risk Analysis

1nd Interpretation

e~e are three ways to obtain an asset: borrow it, receive it as a gift, or earn it. In a corporate setting this translates into boriWing money (securing non-owner financing) , selling shares (receiving capital from owners), or generating profits. We know

Is important to analyze a company's ability to generate operating profits (the third way to obtain an asset). To do this, we

divide the income statement into operating and nonoperating items, and

then focus on operating items. We similarly divide the balance sheet into

operating and nonoperating items to determine the return on net operating

assets (NOA). The 'net' or 'N' in NOA refers to operating assets less operating liabilities, where the latter refers to borrowing from operating sources

{the first way to obtain an asset). In this module we consider borrowing from

Mmeperating sources such as short-term and long-term debt. We explore the role debt plays and how it figures in companies'

e<ilit risk.

Home Depot borrows money from both operating and nonoperating creditors. Its January 2011 balance sheet reveals

t at some of the borrowed money comes from operating liabilities; trade creditors that have shipped inventory to Home Depot

l!li!rt have yet to be paid. This amounts to $4,717 million. Other borrowed money comes from nonoperating liabilities; primarily

l~mgi-term debt. While many companies borrow from banks, Home Depot does not. Its debt is publicly traded. In addition,

lilile Depot reports lease liabilities on its balance sheet which means that the company has borrowed from leasing compaltties or from sellers that provided financing. Given such a wide range of borrowed money, Home Depot's financial condition is

~ftmterest to many types of current and potential creditors, whose overarching concern is whether Home Depot will repay the

lil<:rnnowed money in full and on time. That is, Home Depot's creditors need to assess the company's credit risk.

A credit analysis begins with an understanding of the specific nature of the borrowed money. Suppliers, for example, are

inaturally concerned with Home Depot's short-term liquidity because invoices from suppliers are generally paid within a few

onths of the inventory being shipped. To increase liquidity, Home Depot has established several lines of credit. These are funds

iVailable from Home Depot's bank as needed. In 2011, Home Depot had backup credit facility with a consortium of banks for

l!lerrowings up to $2 billion. The credit facility, which expires in July 2013, provides Home Depot's creditors with some assurance

ti;iat they will be repaid. Suppliers will consider Home Depot's current level of accounts payable as well as its turnover of both

aecounts payable and inventory. If Home Depot maintains historic turnover rates, suppliers can determine when they can expect

l:!!aynnent. This will help them gauge the risk associated with extending credit to Home Depot.

Lenders are interested in the borrower's ability to repay debt over a longer term. For example, in September 2010, Home

lilepot issued $1 billion of Senior Notes, half due in 2020 and the other half due in 2040. Because these notes are long-term,

iilebt investors are concerned with longer-term solvency and cash flow. In addition, these potential investors likely analyzed

0me Depot's expansion plans with a view to understanding whether the company would have sufficient cash to expand and

r:_e111ay the notes.

Several "third parties" are interested in analyzing Home Depot's creditworthiness as well. In particular, credit-rating agenies assess companies' credit risk to determine bond and issuer ratings. These agencies, including S&P, Moody's, and Fitch

(continued on next page)

4 -2

(continued from previous page)

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Ratings, do not have money at risk, but the accuracy of their ratings affects their corporate reputations. Thus, they are interested

in correctly assessing companies' credit risk. In early 2011, the three agencies' ratings of Home Depot were BBB+, A3, and

BBB+, respectively. S&P's rating reflects Home Depot's strength ("substantial U.S. store footprint and recognized name, cost

reductions initiatives that have limited profit erosion through the economic downturn, and meaningful free cash flow generating

ability") as well as its risk factors ("the weak state of the U.S. housing market" and "weak intermediate financial risk profile .. .

and our expectation that leverage will increase"). We explain the various types of analyses that contribute to an evaluation of a

company's credit quality in this module.

Sources: Home Depot Annual Report and 10-K Filing; Moodys.com/ research; StandardAndPoors.com/ratingsdirect.

Home Depot Balance Sheet

- - --...,...--- .-

ou ts in millions, except share and P.2r ~are data

January 30, 201 l

6illrrent Assets

eash and cash equivalents .... . ....... ..... .. .. . ..... . . .... . ......... . . . .. .... .. ... .

meceivables, net . ....... .......... .. . .. ... . . . . . ........ . . ....... .................

~ erchand1se inventories ... . .. ... . . . ..... ................ . . ... .. . . . .. . ... .. . ... . ...

@tliler current assets ...... . ... .. ... ..... .............. . .. .. . . ......... ............ .

. . . .... .. .. . ... . ............ ..... ... . . .. ... ... .... . . . ... ... . .. ......

c

c

z ....

Nm

J>

-4

Ir

l

Credit Risk Analysis

Market for Credit

~ @.

for Credit

Demand

Supply of Credit

11

..!!::..~

Risk Analysis

Chance of Default

Loss Given Default

Credit Ratings

Predicting

Bankruptcy Risk

"'"'

Why Companies Care

How Ratings are

Determined

li

~.'~

Altman Z-Score

Bankruptcy

Prediction Errors

The key to understanding credit risk is to first understand that credit is similar to other commodities-there is a demand for credit and a supply of credit. Firms demand credit for operating,

investing and financing activities and numerous parties are willing to meet that demand incl uding creditors, banks , public debt investors, and other private lenders. Each of these parties is

concerned with repayment and, thus, must analyze the borrower 's creditworthiness. Such analysis follows much of the same model as equity analysis, but the focus is a bit different. While

equity investors are concerned with profitability and earning a return, debt investors have far less

opportunity for upside. That is, debt investors' maximum return is determined by the interest rate

set in the "loan" as well as the prevailing market rate of interest.

This module begins with a discussion of credit markets-the supply and demand for credit.

Then we consider credit risk analysis and explain how operating and nonoperating creditors use

financial accounting numbers and other information to make lending decisions. We learn how

banks make loans to customers and about common loan terms and conditions. The module also

discusses how credit-rating agencies assess companies' credit risk to determine credit ratings and

how ratings affect bond prices and cost of debt capital.

We use Home Depot as the focus company. We reproduce its balance sheet in Exhibit 4.1 and

its debt footnote in Exhibit 4 .2.

DEMAND FOR AND SUPPLY OF CREDIT

LO 1 Understand

the demand for and

supply of credit.

To understand the market for credit, we first consider the demand for credit and then the supply

of credit.

Demand for Credit

Companies demand credit for various operating, investing and financing activities .

Many companies have cyclical operating cash needs. For example,

companies that manufacture inventory have to pay for materials and labor months before they

will be able to sell their product and collect revenue. This is also the case for seasonal companies

4-3

--13,900

25,550

33

1,171

223

- --

---

$ 4,717

1,290

368

1,177

13

1,042

1,515

$ 4,863

1,263

362

1,158

108

1,020

1,589

... .... ..... ............ .. ........ ..... .............. .. ..

10,122

10,363

l!ong-term debt, excluding current installments .. .... ... . ... . . . ... .. .... . ..... . ... . ...

0ther long-term liabilities ... ... . .. . .. .... .. .. . . .. .. . .. . .... . . . . . .. .. .. .. .. .........

Deferred income taxes . . . . . ... .... .. .... ... ........ . ....... ... .................... .

8,707

2,135

272

8,662

2,140

319

Total liabilities ............ . . . . . . .. . .. ................... .......... ...... , .. . . .. .

Sl0ckholders' equity

Common Stock, par value $0.05; authorized: 10 billion shares; issued: 1.722 billion

~nd 1 . 71~ billion shares; outstanding: 1.623 billion and 1.698 billion shares ... .............. .

a1d-1n capital. . . .... . ......... ........ . .. ... . ..... . . .. ..... ..... ... . ........... .

fjletained earnings . ..... .. ....... ..... ........... . .. . ......... .... .. . ...... . . . ... .

Accumulated other comprehensive income ... .. ..... . ........ ....... ... ... .... . .. . . .. . .

ilireasury Stock, at cost, 99 million and 18 million shares

21,236

21,484

86

6,556

14,995

445

(3,193)

86

6,304

13,226

362

(585)

Total stockholders ' equity ....... . . . .......... . ....... . .... .. . .... . . ... ... ... . . . .. .

18,889

19,393

fotal liabilities and stockholders' equity .. . . ... .. . ... .. .. . . . . ....... .. . . .... . . ... . . . . .

$40,125

$40,877

$40,125

L!iabilities and Stockholders' Equity

@1w ent Liabilities

~ccounts payable ................ .. ......... ...... . .............................

~ccrued salaries and related expenses . . .... . .. . ...... ... ... . ........ ................

Sales taxes payable .......... .......... .................. . . .... . . . .. . .... .. ... . .. .

eferred revenue . .......... ...... . .. .. .................. .. . . . .... . . .... . ..... . .. .

income taxes payable ..... ......... . . . . .. .... .............. . .. .. . .. ........ . ..... . .

Current installments of long-term debt. . ....... . . . . . . ... ...... . .. . . .. ... .. . . ... ..... . . .

Gther accrued expenses ... . . . . . . . . . .. ... .. . . .... . . . .. . . . . ... ... .. . .. .. . . . . ... .. . .. .

Total current liabilities ...

$40,877

Debt Footnote for Home Depot

---

In mllions

:Janua

4.625% Senior Notes; due August 15, 201 O; interest payable semi-annually on

February 15 and August 15 . ..... . . . ... . ..... . . . ... . ............ .... .. .... .

5.20% Senior Notes; due March 1, 2011; interest payable semi-annually on

March 1 and September 1 . . ... .... . . . . . ... . . . . . . . . . ... . . . . . ........ . ... .. .

5.25% Senior Notes; due December 16, 2013; interest payable semi-annually on

June 16 and December 16 .. . .... . . . ... ... . . . . . . . ... .... .. ... .... ......... .

5.40% Senior Notes; due March 1, 2016; interest payable semi-annually on

March 1 and September 1 .. .... . .... ... . ... . .......... .......... .. . ...... .

3.95% Senior Notes; due September 15, 2020; interest payable semi-annually on

March 15 and September 15 .. ... ... ................. . ....... ... .......... .

5.875% Senior Notes; due December 16, 2036; interest payable semi-annually on

June 16 and December 16 . . ........ .... . ................ ......... ........ .

5.40% Senior Notes; due September 15, 2040; interest payable semi-annually on

March 15 and September 15 ... ... ..... ... ... ....... .... ....... . . ... ...... .

Capital Lease Obligations; payable in varying installments through January 31, 2055 .... .

30,

20~1

999

1,000

1.000

1,297

1,258

3,033

3,040

499

2,960

2,960

499

452

9

0

408

17

............. .. .... ...... .. . . .. . . . . .. . . ... . . . . --" .. .

9,749

1,042

9,682

1,020

Long-Term Debt, excluding current installments .. . . . ..... . ...... .. . .. ..........

$ 8,707

$ 8,662

Other. . ................. .. . ... ....... ..... . ..... ...... . . .. . . . ........... ..

Total debt

Less curre~~

Operating activities

$ 1,421

964

10,188

1,327

25,060

139

1,187

260

.. ... ........ . ....... ... .. ....... ....... ..... .... .. .... ........ .

..... .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. .. . . .. . . ...... . ....... . ......... . ......... .

..... ... ...... .... ...... ......... .. ... ........... ... ... ... .. ...... ... . .

C>

J>

545

1,085

10,625

1,224

13,479

.. .... ..... ........... ... ... ..... ..... .... ...... ....... ...

:JJ 0

January 31, 20101

~s sets

Total current assets ....... . . . ... . .. ... .... . .. . ... .. .. ..... ... . ..... . . ... . ....... .

4-4

i~st~lj~~~t~

.... ... ... . . . .... . .... . . .. ....... .. .... ... .. ...... . .

~

4-5

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

such as retailers that purchase merchandise for the end-of-year holiday season . Because these

purchases are made long before expected sales , suppliers extend credit to cover the intervening

months . Such seasonal cash needs are routine in nature and credit risk is relatively low. The suppliers' past experiences with a company will dictate the credit terms extended to it. In the event

that suppliers' credit does not extend far enough, a company might need to arrange short-term

loans from their bank.

Cash needed for operating activities is not uniformly "low risk." Contrast cyclical, ongoing

operating cash flow needs as discussed above, with cash needed to cover operating losses. If the

losses are recurring, a company's cash needs might not be temporary unless it is able to return

quickly to profitability. This makes it more difficult for the company to raise capital because of

the increased uncertainty about whether and when it will be able to repay the borrowed amounts .

A company's need for cash can be critical , and finding a willing lender can be the diffe rence

between bankruptcy and continued operations .

Investing activities

Companies routinely require large amounts of cash for investments

including purchases of new equipment and property (capital expenditures) and for corporate

acquisitions. These cash needs vary in timing and amount and are especially important for startups and growth companies that need cash to construct or purchase their initial plant and stores.

For example, in the year ended January 2011, Home Depot opened two new stores in the U.S.

and renovated other stores. They paid more than $1 billion cash for these new assets . As entities

mature , they often settle into more predictable patterns of capital expenditures.

Financing activities Companies occasionally need credit for financing activities, such as

issuance of debt for repayment of maturing debt obligations or the repurchase of common stock.

For example, the $1 billion cash that Home Depot received from the notes issued in September

20 I 0 was used to repay $1 billion of Senior Notes that matured August 15, 2010 .

Supply of Credit

There are numerous parties that supply both operating and nonoperating credit to meet companies' demands .

Trade credit

Trade credit from suppliers is routine and most often non-interest bearing.

Companies apply for credit and provide the supplier with relevant financial information. This

is especially important for private companies that want trade credit. Whereas suppliers can use

publicly available data to evaluate the credit risk of public companies, such information is not

available for private companies. Once approved, customers formally accept suppliers' credit

terms that specify the amount and timing of any early payment discounts, the maximum credit

limit , payment terms, and other restrictions or specifications. Suppliers tailor these contractual

terms to the particular customer's existing and ongoing creditworthiness. For example, suppliers

can set lower credit limits for riskier customers or impose interest payments if credit risk worsens.

ANALYSIS DECISION

You Are the Manager

You have been hired to help grow a start-up. It reported sales of $2 million during the past fiscal

quarter. Currently, it does not offer trade credit, as the majority of its customers use credit cards. In

a bid to expand the business, you are asked to determine whether extending trade credit is a good

idea. What factors are important for you in making this decision? [Answer, p. 4-331

Bank loans Banks structure financing to meet specific client needs . Balancing client needs

are the myriad rules and restrictions imposed by bank regulators. For example , bank regulators

require that banks hold capital (shareholders ' equity) in proportion to their loan portfolio (banks'

main asset). The riskier the loan, the more capital a bank must hold for that loan. Holding capital

is costly and, therefore, banks carefully assess each and every loan application. Bankers often

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Jbave long-term relat~onships wit~ their customers; bankers call this " relationship banking," which

provides the bank with access to mformation needed for detailed credit analysis for different types

6Jf loans .

Revolving credit lines are loans that companies draw on as needed. Revolvers , as they are

alled,

are like credit cards because a company takes cash out as needed and makes payments as

0

eash is available (in uneven amounts). Interest rates on revolving credit lines are often floating,

which means the bank adjusts the rate up or down according to the prevailing market rate of interest. This adjustable interest rate feature limits the bank's interest-rate risk.

Lines of credit are guarantees that funds will be available when needed. To increase liquidiey, companies negotiate lines of credit with their bank or with a consortium of banks. These lines

0 f credit act as backup or interim financing. Often companies use their lines of credit to repay

snort-term commercial paper (discussed below) until more commercial paper can be sold. Ratings

agencies such as Moody's and S&P will not rate a company 's commercial paper unless there is

a line of credit to secure the commercial paper. In the year ended January 2011, Home Depot's

e0mmercial paper program is supported by a $2 billion backup credit facility with a consortium

@f banks. Companies pay for lines of credit in two ways. First, the bank charges a percentage for

~b unused portion of the credit line. This charge ranges from 25 to 100 basis points annually, and

1wmpensates the bank for standing ready to honor a company 's cash demands. Second, the bank

0barges interest on the used portion of the line of credit.

Letters of credit facilitate private international transactions . A letter of credit interposes a

@ank between the two parties to a tran saction. The letter provides a guarantee of payment from

the buyer, is legally enforceable and , therefore , reduces the credit risk to the seller. The benefit

f the letter of credit is that it substitutes the bank's (higher) credit rating for that of the buyer.

!Letters of credit are used mostly to facilitate transactions when the two parties are in different

cwuntries. Recently, letters of credit have been used by land developers to ensure that the proposed

imfrastructure is built.

Term loans are what we commonly understand by "bank loan ." A company applies for the

fan and if successful, receives a set amount of cash at the start of the loan (the principal). The

foan agreement specifies periodic payments of principal and interest. Interest rates are either fixed

0F floating and a term loan will usually mature between 1 and I 0 years. Many banks actively

market small-business term-loan programs that provide companies with needed operating cash or

runds to purchase long-term assets such as equipment.

Mortgages are loans secured by long-term assets such as land and buildings , which means

that the lender can foreclose on the mortgage and seize the property in the event of default. Mortgage claims are filed with a public register such as local land title offices. Because a mortgage

is often a company's largest debt , mortgage lenders perform due diligence before lending . For

tHi.ample, a mortgage lender will verify income statement and balance sheet information and run

tiiVle searches to ensure that there are no prior claims on the property.

lfJonbank private financing Companies occasionally borrow from nonbank private

lenders , usually when they have been turned down for a loan from a traditional bank. Private

enders might fund higher risk ventures because they have a better understanding of the business or a particular market segment. In addition to providing funds , some private lenders will

ti.P.eatively structure loan repayment and sometimes act as an ongoing management consultant

t0 the borrower.

RESEARCH INSIGHT

Nonbank Private D.ebt

Researchers David Denis and Vassil Mihov study companies' choices among public debt, bank debt,

and private nonbank debt. They report that public borrowers are more profitable and have higher asset

turnover. However, the main determinant of a company's choice is its credit rating. Those with the

highest credit quality issue public debt, those with medium credit quality borrow privately from banks,

and those with the lowest credit quality (have not established a strong credit reputation) borrow from

nonbank private lenders. (Source: Choice Among Bank Debt, Non-Bank Private Debt and Public Debt: Evidence From

New Corporate Borrowings, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id = 269129)

4-6

4-7

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Lease financing An alternate form of borrowing is leasing. Leasing firms finance capital

expenditures for equipment such as vehicles, production machinery, and computer equipment.

Some leasing firms are associated with the equipment manufacturer (such as GMAC or Ford Credit

or IBM 's financial services). Other leasing firms are independent and provide a full range of lease

services. The leasing firm analyzes the credit risk associated with the lease, bearing in mind that the

leased assets are held as collateral, and that some of the risk can be mitigated by tailoring the lease

terms. At the end of January 201 I, Home Depot reported on its balance sheet lease obligations of

$452 million; payable in varying installments through January 31, 2055.

Publicly traded debt Issuing debt securities in capital markets is a cost-efficient way to raise

capital. Companies issue short-term or long-term debt depending on the specific need for funding.

Commercial paper is short term; because maturities do not exceed 270 days the borrowing is

exempt from SEC regulations. Companies use proceeds from commercial paper to finance shortterm operating or working capital needs. Commercial paper is issued primarily by financial companies (commercial banks, mortgage companies , leasing companies, and insurance underwriters)

although large manufacturers and retailers also issue commercial paper. Home Depot did not have

any commercial paper outstanding at year end, January 30, 2011. The year before, it had an average

daily commercial paper balance of $55 million but this was repaid by the end of the fiscal year. It

is most often the case that companies pay a lower rate of interest for short-term commercial paper

than for longer-term bonds or notes . The average interest rate on Home Depot's commercial paper

during fiscal 2010 was 1.1 % .

To secure longer-term funding, companies issue bonds or debentures. For example, at January 30, 2011, Home Depot had long-term debt of$ 9 ,288 million arising from Senior Notes which

mature between March 2011 and September 2040. Home Depot's debt footnote, reproduced in

Exhibit 4.2, shows that interest rates on those notes range from 3.95% to 5.875 % . Debt that is

offered for sale to the public is regulated by the SEC even if the company's stock does not trade

publicly. Generally, the entire face amount (principal) of the bond is repaid at maturity, and taxdeductible interest payments are made in the interim (nearly always semiannually). After they are

issued, corporate bonds can trade on major exchanges but most of the trading is decentralized,

as dealers trade the bonds in over-the-counter markets. Investors who buy the bonds when they

are issued and in subsequent re-sales, are concerned with the issuing company's ability to meet

semiannual interest payments (short-term liquidity) and to repay the principal at maturity (longterm solvency and cash flow coverage).

MID-MODULE REVIEW 1

Rising Sun Company is a successful importer of traditional Japanese food. The company is privately held and has operated since 1982. Revenues and net income for the most recent fiscal year

were $82 million and $9 million, respectively. Currently located in San Francisco, the company

is considering expansion into the Seattle area. Management has prepared a business plan and estimates that the company needs $15 million to complete the plan, including $6 million to purchase

land and construct a storage facility; $2 million for office equipment and leasehold improvements

for rented office space; $5 million for inventory purchases; and $2 million to pay permit fees, rent,

wages, and other operating expenses in the first few months until revenues are realized.

Required

What sources of financing should Rising Sun Company consider? Discuss each source.

The solution is on page 4-45.

Expected credit loss

= Chance of default x

4-8

Loss given default

B,ef~re we discuss how l~nd_ers assess_t~ese two factors, consider that the number and types of

wart1es who perform credit nsk analysis 1s broad and varied: trade creditors , banks and nonbank

financial institutions, debt investors (including participants in public debt markets) , and credit

rrating agen~ies. The_ key distinction among the groups is the nature of the information they use in

tfu.eir a~alys1s. That is, not ~11 lende_rs have access to the same information and, thus, each group

tailors its approach to credit analysis.

Trade creditors acquire additional information via credit applications. Given its size and repulta~i on , Home _Depot ha~ l~ttle diff~culty attracting trade credit, and information is publicly availa11Jle to p~tent1al a_nd ex1s~111g creditors. But for private companies, the credit application might be

~fu.e on~y mformat1on available to a potential lender. Trade creditors check applicants' references,

'ncludmg trade references (names of other trade creditors, their respective credit limits, outstanding balances, and any nonpayment information) and bank references (names of bankers and the

amounts ~f any lines of credit). Because trade creditors often extend credit to many customers in

~he same mdustry, the chance of default can be highly correlated among customers. Thus trade

eneditors closely monitor information on industry trends and outlook.

Banks and no?bank financial institutions have access to information that managers do not

release to the pubhc. Moreover, bankers typically negotiate the loan and adjust loan terms to fit

the c~anc~ of default fo_r each client. As well, banks can monitor bank balances and act on early

wammg signs. Thus, pnvate lenders are in a unique position to refine their credit analysis.

In c?ntrast, public-debt investors have little access to additional information; they can

Gmly decide to buy or sell the bond at the current price. They have access to public information

including earnings announcements and annual reports (see Research Insight below) . Public-debt

i m:e~tors al~o can avail themselves of debt ratings (which we discuss later), but apart from that,

eubhc-debt investors have publicly available information only.

S~mi l a~ to lenders_ and investors, credit raters assess credit risk, but their purpose and methds differ m several important respects. First, credit rating agencies have no direct financial

invo~vement ':ith the _compa~ies whose credit they are rating; they perform the analysis to

p~ov1de a publicly available signal to lenders and potential lenders. Second, credit rating agene;ies ha~e access to m~re, and often better, information than other lenders. Credit analysts are

lil@t subject to Regulat10n FD and routinely meet with managers both in conference calls and

>ace to face. Thu~ c_redit-rating agencies can refine the risk analysis for individual companies

and compare statistics and trends across companies. Credit raters have the best, most current

Information. It is for this reason that other creditors rely heavily on credit ratings. [On August

5, 2000 , the SEC adopted Regulation Fair Disclosure (FD) to curb selective disclosure of

iimformation

publicly_tr~ded companies. Reg FD requires that if a U.S. public company disGJl0ses _matenal nonpublic mformation to a select group (such as equity analysts), the company

~ ust simultaneously disclose the information to the public. The regulation levels the informal <lln playing field .]

?Y

RESEARCH INSIGHT

Accounting Earnings and Bond Prices

Researchers Peter Easton, Steven Monahan, and Florin Vasvari study how companies' earnings

announcements affect bond prices. They document large changes in bond prices around earnings

announcements and find that these changes are larger for net losses. Thus, companies with public

debt have strong incentives to avoid losses because they depress bond prices. These researchers

also find that bond-price changes are larger for speculative grade bonds. A main inference is that

accounting earnings (and its components) are priced in bond returns. (Source: Initial Evidence on the Role

of Accounting Earnings in the Bond Market, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=997821)

CREDIT RISK ANAL VSIS PROCESS

L 0 2 Explain the

credit risk analysis

process.

The overarching purpose of credit risk analysis is to quantify potential credit losses so that lending

decisions are made with full information. Expected credit losses are the product of two factors,

the chance of default and the size of the loss given default. This is algebraically reflected as

follows:

~NAL YZING CREDIT RISK

l . he main purpose o f a ered tt ana Iys1s

1s

to quantify

the risk of loss from nonpayment. To quantify expected credit losses, potential lenders must assess the chance of default and the size of

L03 Perform a

credit analysis, and

compute and interpret

measures of credit risk.

4-9

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

the loss given a default. While lenders have different information sets and use different credit

analysis models, there are four common steps to determine the chance of default. We di scuss

each of these four steps and we consider how creditors might limit their losses in the event of

default.

Chance of Default

The chance of default depends on the company' s ability to repay the debt which , in turn,

depends on the company 's future performance and cash flow. Different lenders approach credit

analysis with different techniques . The following discussion is comprehensive, and not a script

that any one creditor follows. As a starting point, the analysis considers the company 's past

performance and its current financial condition , projects future cash flows , and determines a

probability that a company will have insufficient cash to repay the loan.

Step 1 : Assess nature and purpose of the loan

A necessary first step for the prospective lender is to determine why the borrower needs the

loan . If one cannot be assured of the need for credit, proceeding to the analysis stage is pointless . As we explained, there are many reasons to borrow (for cyclical cash flow needs, to fund

temporary or ongoing operating losses, for major capital expenditures or acquisitions, or to

reconfigure capital structure). The nature and purpose of the loan affect its riskiness. Lending to

a company that needs funds for ongoing operations is riskier than a company that needs funds

to expand into a new profitable market segment. In the year ended January 2007, Home Depot

borrowed almost $9 billion , using some proceeds to repay maturing debt, fund the repurchase

of stock, and to acquire Hughes Supply, Inc. That year, the company also sold commercial

paper to support short-term liquidity needs. The nature and purpose of the loan also affect the

focus and depth of the lender's credit analysis . For example , trade creditors will not do as indepth an analysis as a mortgage lender. Each computes and analyzes the same types of ratios

but their emphases will differ.

Step 2: Assess macroeconomic environment and industry conditions

Like financial analysis, credit analysis must consider the broader business context in which a

company operates. The nature of the competitive intensity in the industry affects the expected

level of profitability. Global economic forces affect the macro economy in which the company

operates . Government regulation , borrowing agreements exacted by creditors, and internal

governance procedures also affect companies ' range of operating activities. Such external

forces affect companies' strategic planning and expected short-term and long-term profits. A

company's relative strength within its industry, and vis-a-vis its suppliers and customers, can

determine both profitability and its asset base. As competition intensifies , profitability likely

declines, and the level of assets needed to compete likely increases. These changes in the

income statement and the balance sheet can adversely impact operating performance and cash

flow and the company's ability to repay its debts. There are several ways to systematically

consider broader business forces . We discuss one such framework: Porter's Five Forces (Porter,

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1980 and 1998);

and we assess each force for Home Depot.

(A) Industry competition Increased rivalry raises the cost of doing business as companies must

compete for workers, advertise products, and research and develop new products. Home Depot 's

industry competition is intense. Its biggest rival is Lowe's Companies . In many markets , Lowes

and Home Depot compete directly for the same do-it-yourself customer. Smaller hardware stores

and lumber yards create additional rivalry (such as Ace Hardware and Sears). Competition also

arises from specialty stores that focus on one aspect of home improvement such as flooring, kitchens, lighting, and roofing. Home Depot's garden center faces competition from national nurseries,

and most cities have large local nurseries and garden specialty shops. Increasingly, Home Depot

faces competition from online vendors such as US Appliances, iFloor, and nurseries such as

Autumn Ridge and Henry Fields .

rfJJBuyer power

Buyers, the customers , with strong bargaining power can extract price concessi<'>ns and demand a higher level of service and delayed payment terms ; further, a company that

faees strong customers has decreased profits and operating cash flows . Home Depot's buyer

p0wer is low. Home Depot has three types of customers: do-it-yourself (DIY) customers, buy-itfurself customers (those who like to pick out materials and appliances but want a professional to

ltnstall them), and the professional customer (contractors, plumbers, landscapers). None of these

011 stomers has strong bargaining power with Home Depot, although the company does now offer

~arge-quantity purchases and separate staff to assist professional customers.

(,6) Supplier power Suppliers with strong bargaining power can demand higher prices and

earlier payments; a company that faces strong suppliers has decreased profits and operating cash

filews. Home Depot's supplier power is low. A typical Home Depot store has 40,000 different

pJoducts purchased from many suppliers. It often accounts for a large portion of,a supplier's sales.

'U his decreases the supplier's power and Home Depot can command lower prices and longer payent terms. These sorts of concessions increase Home Depot's margins.

(DJ Threat of substitution As the number of product substitutes increases, sellers have less

p0wer to raise prices and/or pass on costs to buyers; accordingly, threat of substitution places

!ll0wnward pressure on sellers' profits. At Home Depot, the threat of substitution is low to medium. There are few substitutes for home improvement and the nesting instinct is timeless . Home

Wepot offers in-store "How To" classes that customers can substitute with online instructions

and do-it-yourself videos. In times of economic growth, new-home purchases are a substitute but

liFJresent a minimal threat because even new home owners want to decorate, landscape, and make

(l)ther improvements.

(EJ Threat of entry New market entrants increase competition; to mitigate that threat, compa. ies expend monies on activities such as new technologies, promotion , and human development

t0 erect barriers to entry and to create economies of scale. Home Depot faces a weak threat of

1mtry in the form of big-box retailers. New market entrants would find it difficult to compete

~Urectly with Home Depot and Lowes. Both companies enjoy economies of scale and are protected by barriers to entry including trained workforce, large capital start-up costs , prime locati0ns, national brand recognition, and customer loyalty. However, threat of entry from online and

swecialty stores is medium to high.

In sum, the industry in which a company operates dictates much of the company's potential

profitability and efficiency. Home Depot does business in a highly competitive market but enjoys

l0w supplier and buyer power. This indicates that, at least in the short run, the company should

11'.emain profitable and the chance of default is relatively low.

Step 3: Perform financial analysis

~ financial analysis includes calculating ratios . But ratios are only as accurate as the numbers

in the numerator and denominator. Thus, it is crucial to begin with high-quality inputs . In later

ffi(\)dules we explain adjusting the financial statements to ensure the quality of the numbers. We

adjust the financial statement to exclude one-time events or transactions that will not persist and

include all assets and liabilities at proper amounts; both for purposes of increasing the quality

<il'f the ratio inputs. From the adjusted financials , we calculate ratios and then compare them to the

ratios of competitors as well as to broader industry averages .

Apart from earnings per share (EPS), GAAP does not define ratios. Some ratios (such as

:Urrent ratio) are universally defined but many more ratios have no unique, commonly accepted

definition. For example, the debt to equity ratio is defined as either total liabilities to equity or

ias total debt (interest bearing liabilities) to equity. Similarly, measures such as free cash flow or

EBITDA , which are inputs to ratio calculations , often have more than one definition . One version of free cash flow deducts capital expenditures from operating cash flow. Another version

also deducts dividends paid . It is not possible to specify the "correct" way to compute ratios. The

~est advice is to know what is in the numerator and denominator of any particular ratio and then

mterpret the quotient accordingly.

Just as no two analysts compute ratios the same , there is little agreement about the best set

of ratios to assess credit risk. For example, this module 's Appendix shows a list of ratios (along

4-10

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

4-11

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

with their definitions) that S&P and Moody's use to prepare credit ratings. The ratios are widely

divergent and similar ratios are defined differently by the rating agencies.

For our purposes, we compute three classes of credit-risk ratios: profitability and coverage,

liquidity, and solvency. Profitability and coverage ratios are called "flow" ratios because they

include cash flow and income statement data. The liquidity and solvency ratios are called "stock"

ratios because they use balance sheet numbers only. We use both flow and stock variables to

assess credit risk.

Adjusted financial statements As a prelude to the analysis process, we analyze current

and prior years' financial statements to be sure that they accurately reflect the company's

financial condition and operating performance. Why? The answer resides in the fact that

general-purpose financial statements prepared in conformity with GAAP do not always accurately reflect our estimate of the "true" financial condition and operating performance of, the

company. Accordingly, before we begin the analysis process, we analyze historical financial

statements to be sure they reflect our estimate of the "true" financial condition of the company

and consider adjustments when those reports are inconsistent with reality. Later modules assess

BUSINESS INSIGHT

Prior to its ratio analysis, S&P adjusts companies' balance sheets and income statements for the following:

Operating leases

Take-or-pay contracts

Debt of joint ventures and unconsolidated subsidiaries

Factored, transferred, or securitized receivables

Financial guarantees

Contingent liabilities

The table below shows some of the adjusted numbers S&P used for its credit analysis of Home Depot in 2010. For example,

see that S&P adjusts Debt (column 1) to include $4,961 million of operating leases and $940.6 of other items including

pension related obligations. We consider these topics in Module 9.

4-12

tl'le accounting and measurement of assets and liabilities, from which we will be able to make

nformed judgments about the adjustments necessary to reflect the true financial condition and

erformance of the company. 1

rpr.ofitability analysis Profitability is related to credit risk because firms wish to pay interes~ and repay their debt with cash generated from profits . The more profitable the firm, the

~ess likely it is to default on its debt. S&P's Rating Methodology: Evaluating the Issuer lays

0 ut an additional consideration, "a company that generates higher operating returns has a

greater ability to generate equity capital internally, attract capital externally, and withstand

lbusiness adversity. Earnings power ultimately attests to the value of the firm's assets as well."

0 this point, on August 30, 201 I, Moody's upgraded Home Depot's rating to A3 from Baal

t:>ecause the rating agency was impressed by the company 's strong operating performance

(ifuring the second quarter. "Home Depot's significant improvement in its in-store shopping

~xperience and supply chain will continue to benefit its earnings. The rating also reflects

0me Depot's notably improved execution ability which has resulted in its comparable store

salles out performing Lowe's for the past nine quarters ." (Source: Moodys.com/research/

~0odys-upgrades-Home-Depots-senior-unsecured-rating-to-A3 - PR_225225 .)

Module 3 describes in detail how to analyze a firm's profitability using return on net operating assets (RNOA) and its component parts: net operating profit margin (NOPM), which measures the profit earned on each dollar of sales; and net operating asset turnover (NOAT), which

measures the efficiency of operating assets. This type of profitability analysis is applicable for

credit analysis.

Home Depot's income statement for the year ended January 30, 201 I, is in Exhibit 4.3. Home

Depot's net operating profit after tax is $3 ,696 million, computed as $5 ,839 million - [$1,953

million + ($566 million X 36.7%)].

Income Statement for Home Depot

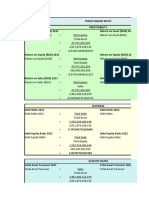

Reconciliation of Home Depot Reported Amounts with Standard & Poor's Adjusted Amounts

HOME DEPOT

Fiscal year ended Jan. 31, 2010

Income Statement

lmlllions

Debt

Reported ......... . .....

9,682.0

Standard & Poor's adjustments

Operating leases . .. .....

4,961.0

Additional items

included in debt .......

940.6

Capitalized interest ... ....

Share-based

compensation expense ..

Reclassification of

nonoperating income

(expenses) .. . . . .......

Reclassification of

working-capital cash

flow changes ... . ......

5,901.6

Total adjustments .. . .....

Standard & Poor's

adjusted amounts* .....

15,583.6

Operating

income

(before

D&A)

Operating

income

(before

D&A)

6,656.0

803.0

Operating

income

(after

D&A)

Interest

exponse

6,656.0

4,949.0

418.9

418.9

Cash

flow from

operations

Cash

flow from

operations

Capital

expendituresf

676.0

5,125.0

5,125.0

966.0

418.9

384.1

384.1

448.7

4.0

(4.0)

(4.0)

I Year Ended (in millions)

(4.0)

201 .0

January 30, 2011 January 31, 2010 February 1, 2009

et sales .. ... . ... . ..... . . . .......... . .... . . . .... . ......... . ... . . .

G::ost of sales ..................... . ............................... .

$67,997

44,693

$ 66,176

43,764

$71,288

47,298

Gress profit. ................................................ . ... . .

Ofilerating expenses

Selling, general and administrative . . .. . . . ........................ .. .. .

ill>epreciation and amortization ... . ... . . . .. ...................... .. .. . .

23,304

22,412

23,990

15,849

1,616

15,902

1,707

17,846

1,785

1Jiotal operating expenses ....... . ... . ........................ . . .. . . . .

perating income ............... . . .. .......................... . . . . .

l.@terest expense and other, net ...... ... ... . . . ... . .......... . . .. . . . . . .

17,465

5,839

566

17,609

4,803

821

19,631

4,359

769

Earnings from continuing operations before provision for income taxes . . . . ... .

ffirovi sion for income taxes . . . . ... ..... .. ... ...... . .. . .. .. . . . .. .... . . .

5,273

1,935

3,982

1,362

3,590

1,278

earn ings from continuing operations . ..... ........ . ..... . ....... . .. . . .

liarnings (loss) from discontinued operations, net of tax ........... .. ... . .. .

3,338

2,620

41

2,312

(52)

l'llet earnings ...................... .. .... ..

$ 3,338

---

18.0

(521.0)

803.0

619.9

436.9

422.9

380.1

7,459.0

7,275.9

5,385.9

1,098.9

5,505.1

[Operating

income before

[EBITDA)'

[EBll]

[Cash flow from

operations]'

(140.9)

4,984.1

--$ 2,661

444.7

1,410.7

[Funds from

operations]"

D&Al'

Home Depot Inc. reported amounts are taken from financial statements but might include adjustments made by data providers or reclassifications made

by Standard & Poor's analysts. Two reported amounts (operating income before D&A and cash flow from operations are used to derive more than one

Standard & Poor's-adjusted amount (Operating income before D&A and EBITDA, and Cash flow from operations and Funds from operations, respectively).

Consequently, the first section in some tables may feature duplicate descriptions and amounts.

Home Depot's net operating assets for 2011 and 2010, respectively, are $27,954 million

and $27,621 million. 2 Thus, the company's RNOA for 2011 is 13.3%.3 RNOA dropped sharply

1

For simplicity, we compute ratios in this module using numbers reported instead of adjusted numbers. We al so do

this so that we can compare its ratios to other companies' ratios. An alternate , more exact, approach is to recompute all

~ompetitors' numbers and create adjusted industry -level ratios.

2011: ($40,125 million - $545 million - $139 million) - ($21,236 million - $1,042 million - $8,707 million) .

2010:

($40,877 million - $1,421 million - $33 million) - ($21,484 million - $I ,020 million - $8 ,662 million)

J ~

<Jlj,696 million/[($27,954 million + $27 ,621 million)/2]

$ 2,260

4-13

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

after the fiscal year ended January 2008 , after housing starts markedly slowed and the recession

kicked in. Since then , profitability has steadily improved but has not returned to pre-recession

levels .

Home Depot's return on equity (ROE) for 2011 was 17.4%.4 Companies can effectively use

debt to increase returns to shareholders. By comparing ROE and RNOA (see graphic below)

we can see the power of this leverage. During 2011, Home Depot had a nonoperating return

of 4.1 % ( 17.4% - 13 .3 %) because the company borrowed money at an average, after-tax rate

of 4% and invested it in profitable operating activities that earned 13.3%. Financial leverage

(FLEV) measures companies' relative use of debt to equity. In 2011, Home Depot's FLEV was

0.45, computed as average FLEV for 2011 and 2010. For 2011, FLEV was 0.48 : ($1 ,042 +

$8,707 - $545 - $139)/$18,889; and for 2010, FLEV was 0.42: ($1,020 + $8,662 - $1,421

- $33)/$19 ,393) . This means that for every dollar of equity, the company had $0.45 of net

nonoperating obligations (primarily short and long-term debt). The higher the FLEV the greater

the nonoperating return . However, as companies ' debt increases (higher FLEV) so does the risk

of default. Companies like Home Depot balance the benefit of leverage with this increased risk.

Ideally, numbers in the RNOA analysis are adjusted to better reflect a company 's economic

profitability. We exclude items that we expect will not persist to reveal a more accurate picture of

the company's future profitability (as well as for liquidity, solvency, and cash flow). All ratios we

compute in credit analysis should use these adjusted income statement items as inputs. An examination of Home Depot's income statement and footnotes reveals no material one-time charges.

tcBITDA Coverage Ratio

f;arnings before interest, tax , depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) is a non-GAAP performance metric commonly used by analysts and investors. EBITDA coverage is defined as:

IBITDA coverage

= Earnings before tax + Interest expense, net + Depreciation + Amortization

~~~:__~~~~~~~~---'~~.:__~~~~~::..:....:..::..::..::.::.___:__.:.=:::.::.:...:::==::..:::

Interest expense

JFhe ratio is similar to times interest earned ratio, but more widely used because depreciation does

nt require a cash outflow and, thus, more cash is available to "cover" fixed debt charges than

6AAP earnings would convey. Other versions of the ratio add back only amortization, or include

gross interest expense in the denominator. See the module's Appendix for a list of ratios used by

ratings agencies. The EBlTDA coverage ratio is always higher than times interest earned (because

0f the depreciation add back) but measures the same concept: the companies ' ability to pay interest out of current profits. The graphic below compares Home Depot's times interest earned ratio

t0 EBITDA coverage.

Home Depot Coverage Ratios

25%

RNOA

l---+--------1

20%

15%

10%

5%

2008

2009

2010

2011

Coverage Analysis Coverage ratios compare operating profits or cash flows to interest and/or

principal payments. We use coverage ratios along with RNOA and ROE, to assess the company's

ability to generate profit and cash to cover the fixed charges from debt (interest and principal) in

the short and long term.

Times interest earned The times interest earned ratio reflects the operating income available to

pay interest expense and is defined as follows:

Times interest earned

Earnings before interest and taxes

t

1n erest expense

The underlying assumption is that only interest must be paid because the principal will be refinanced. The numerator is similar to net operating profits after tax (NOPAT), but it is pretax

instead of after tax. Management wants this ratio to be sufficiently high so that there is little risk

of default. Home Depot's 2011 times interest earned ratio is 10.9 ($5,803 million/$530 million).

The ratio was 7 .0 in 20 IO ($4,699 million/$676 million) . The 2011 increase is a result of increased

profitability coupled with a drop in interest expense.

4

$3 ,338 million/1($19,393 million + $18,889 million)/2]

4-14

Pash from operations to total debt A company 's liquidity depends critically on its ability to

generate additional cash to cover debt payments as they come due. The times interest earned and

~BITDA coverage ratios assume that the company needs to "cover" interest payments only each

~ear because the principal owing will be refinanced. This is not always a valid assumption. To

Jilileasure a company's ability to repay principal in the short and longer term, we can use the operatililg cash flow to total debt ratio. The ratio is defined as follows (related ratios exist that measure

a company's ability to generate additional cash to short-term debt and long-term debt):

,

.

.

Cash from ____:

operations

Cash

from

operations

to total debt = _______

_________

Short-term debt + Long-term debt

Fer the year ended January 30 , 2011 , Home Depot's statement of cash flows reported cash from

(l)perations of $4,585 million. Home Depot's cash from operations to total debt ratio was 0.47 in

~Cill l ($4,585 million/[$1,042 million + $8,707 million]). This ratio hovers around 0.5 for Home

~epot as the graphic on the next page shows.

'Dnee operating cash flow to total debt Companies must replace tangible assets each year to

\\l@ntinue operations. Any excess operating cash flow after cash spent on capital expenditures

~CAPEX) is considered "free" cash flow in that the company is free to use the cash for other

purposes including debt repayments . Some creditors use the following free cash flow measure as

another coverage ratio.

Cash from

- CAPEX_

. cash flow to total debt = ___

Free operatmg

__operations

_;;__ _ _____

Short-term debt + Long-term debt

4-15

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

The free operating cash flow to total debt ratio is argued to reflect a company's ability to repay del\

from the cash flows remaining after CAPEX. For t~e year en~ed January 30, 20_1~ , Home Depot'

statement of cash flows reported cash s~nt for_cap1tal expenditure~ ~f $1,096 million: ~hus, its f~

operating cash flow to total debt ratio is 0 .36 m ~O 11 ([$4,585 million - $1,096 mill1on)/[$ l ,0

4

million + $8,707 million]). This ratio was higher m 2011 and 20 l 0 compared to the two prior ye

(see graphic below). This increase has two drivers: (I) Home Depot's CAPEX was much higR

.

.

1teri

before the recession of 2008--09, and (2) the company had more debt m pnor years.

There are many variations of liquidity, solvency, and coverage ratios. The basic idea is t(i)

construct measures that reflect a company's credit risk exposure. There is not one "best" finanoj~

ratio. Instead, as financial statement users, we want to use measures that capture the risk we ai:_e

most concerned with . It is also important to compute the ratios ourselves to ensure we know whan

is included and excluded from each ratio.

4-16

"l:;)Jes and inv~ntories and ma~imizi~g payables . Dell is the classic example of an efficient

~urer with httle to no working capital.

:iJ@U[, Home Depot's current ratio was 1.33 and it has fluctuated within a range of 1.15 to

~eJ ~he previous three years, as shown in the graphic. Home Depot is a cash-and-carry busi!il ti!, tibus, we do not e~pect its current ratio to be as high as companies that carry a high level

e all>les. Given that its current ratio exceeds 1.0, Home Depot seems reasonably liquid.

Home Depot Liquidity Ratios

1.40

1.35

0.20

1.30

0.16

Home Depot Cash Flow Ratios

1.25

0.60

0.12

1.20

0.08

1.15

0.50

0.04

1.10

0.00

0.40

0.30

0.20

atio The quick ratio is a variant of the current ratio. It focuses on quick assets, which are

0 1 IL__2_0_08_ _c.___ 20_0_9_ __.:____2_0_1_0_

2_0_11_ _,

_L__ _

Operating Cash Flow to Debt

Free Cash Flow to Debt

Liquidity Analysis Liquidity refers to cash availability: how much cash a company has, and

how much it can generate on short notice. In this section, we discuss several of the most comm0n

liquidity measures: the current ratio, working capital , and the quick ratio .-~

Current Ratio Current assets are assets that a company expects to convert into cash within tl't

next operating cycle, which is typically a year. Current liabilities are those liabilities that come

due within the next year. An excess of current assets over current liabilities (Current assets. Current liabilities), is known as net working capital or simply working capital. Positive work1~g

capital implies more expected cash inflows than cash outflows in the short run. The current ratt

expresses working capital as a ratio and is computed as follows:

Current assets

Current ratio = C

b'I' .

urrent 1ia 1 1ties

Positive working capital or a current ratio greater than 1.0 both imply more expected cash inflows

than cash outflows in the short run. Generally, companies prefer a higher current ratio (mote

working capital); however, an excessively high current ratio can indicate inefficient asset use ..~

current ratio less than 1.0 (negative working capital) is not always a bad sign. For example, ~etatf

ers carry inventory that is about the same value as accounts payable and, thus, working capital 1

near zero. If the inventory is sold as anticipated, sufficient cash will be generated to P~Y .cu:r~

liabilities. Other companies are especially efficient at managing working capital by mmimizing

60

we compute rat10s

m this

module using

num bers reporte d mstead o f a d.JUSte d num be rs We also ,J

s For simpltc1ty,

this so that we can compare its ratios to other companies' ratios. An alternate, more exact, approach is to recompute

competitors' numbers and create adjusted industry-level ratios.

s likely to be converted to cash within a relatively short period of time. Specifically,

include cash, marketable securities, and accounts receivable; they exclude invento,!!I 11ut~paid assets. The quick ratio is defined as follows:

. k

.

Qmc ratto

' ,GJ(

Cash + Marketable securities + Accounts receivables

= ---------------------Current liabilities

mtfo gauges a company's ability to meet its current liabilities without liquidating inven-

~lii.at e@uld require markdowns . It is a more stringent test of liquidity than the current ratio.

!Depot's 2011 quick ratio is 0.16, computed as ($545 million + $1,085 million)/$10,122 mils lilGt uncommon for a company's quick ratio to be less than 1.0. Home Depot's 2011 quick

@wer ~han in 2010 but higher than the previous two years, as the graphic shows. This is due

en accounts receivable but less cash in 2011 compared to 20 I 0. In 2011, the current ratio

ab<rM the same as the prior year but the quick ratio drops. This signals a potential buildup

' t@.cy, which is something financial statement users should monitor.

~c:y~nalysis Long-term solvency analysis considers a company's ability to meet its debt

Utns, including both periodic interest payments and the repayment of the principal amount

em. !Il'he general approach to measuring solvency is to assess the level of liabilities relative

~ Ther are a variety of ratios used to gauge solvency; all use balance sheet data and

' e 19rnportion of capital raised from creditors. We discuss two solvency ratios: liabilitiesalild long-term debt to total capital.

The liabilities-to-equity ratio is defined as follows:

.

Total liabilities

. b' .

L ia

1hties-to-eqmty ratio = - - - - - - - - Stockholders' equity

c n

hov reliant a company is on creditor financing compared with equity financ~g r rali indicates a le s solvent company. The median ratio of total liabilities-to-equity

Wless than 1.0 for publicly traded companies. This means that the average company is

Note: Debt is

normally a less

costly source of

financing vis-a-vis

equity financing.

Although less

costly, debt carries

default risk: the risk

that a company is

unable to repay debt

principal and interest

when it comes due .

4-17

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

financed with about half debt and half equity. However, the relative use of debt varies considerably across industries as illustrated in Exhibit 4.4.

Median Ratio of Liabilities-to-Equity for Selected Industries

Median Ratio of Liabllltles-to-Equlty

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

o0

f.(.o

0.0 -JL-----1-1'--~-__,IL---~---~1'--~--~IL-~-~----:<---__,'

~o

l.v

""'~

~...~

J>"

~~

-~'li

(>~

-~q,"

.;::,-::>

~o~

~~

Cf

~~

~

~vo/"

q;.v

~

&~

q,v

rtlr;;

rtl<f

q_~

~~(/;

r,his solvency r~ti~ as~umes that current operating liabilities will be repaid from current assets

~so-called s~lf~hqu1dati~g) s~c? that lenders should focus on the relative proportions of debt and

~~uity. (V~nations of this rat10 mcl~de o~ly l~ng-term debt in the numerator and/or total capital in

vli\denommator; these solvency rat10s differ m their exact definitions but all assess the company's

(llawital structure and measure the relative debt load.)

Home ~epot's 2011 ratio was 0.52 (($1,042 million+ $8,707 million)/$18,889 million] about

:De same as m 2010 but marked~y lo~er than in 2008 when the ratio was 0.76-see graphic above.

Jl{0.me D~pot has less debt than m pnor years and, consequently, both solvency ratios are stronger.

Dunng 2011, Home Depot repurchased $2.6 billion of common stock. The effect of this

as to decrease solvency but only by a fraction because Home Depot also repaid debt dur'ng the y~a~. At the ~nd of 201?, S&P addressed Home Depot's stock buybacks, saying, "The

e?1pany s mtermediat~ financial risk profile is somewhat weak for the 'BBB+' rating, and

t includes our expe~t~tion that leverage will increase due potentially to future debt-financed

sl:tare repurchase activity. As of Aug. l, 20 l 0, we estimate the company could add about $3 bilLi@n debt to repurchase shares and remain below 2.5x leverage. We currently believe such debt*iinanced share repurchases would only occur when the company believes the environment has

vabilized." I.n sum, Home Depot's ratio analysis reveals a profitable company that effectively

il!Jses de~t to mcr~ase return~ to. s~areholders, a company with strengthening coverage and cash

0w rat10s, and improved hqmd1ty and solvency.

Companies in the food, transportation, capital goods, and utilities industries have among the

highest proportions of debt. Because the utilities industry is regulated, profits and cash flows are

relatively certain and stable and, as a result, utility companies can support a higher debt level. The

other three industries also utilize a relatively high proportion of debt. However, these industries

are not regulated and their markets are more competitive and volatile. Consequently, their use of

debt carries more risk. At the lower end of debt financing are software firms whose profits and

cash flows can be very uncertain; and pharmaceutical firms whose persistently high profits and

cash flows reduce the need for debt financing.

Home Depot's total liabilities-to-equity ratio is l.12 in 2011 ($21,236 million/$18,889 million), a marked drop from l .5 in 2008-see graphic below. Home Depot's ratio is much lower

than the average for retailing firms (1.5) and just slightly above 1.0, the average for publicly

traded companies.

Step 4: Perform prospective analysis

'.ll0 evaluate the creditworthiness of a prospective borrower, creditors must forecast the borllW~r's cash flows to estimate. its ability to repay its obligations . To effectively look forward,

e fa~st. mus~ look back. That 1s, the forecasting process begins by adjusting current and prior

&ears financial statements so that they accurately reflect the company's financial condition and

Jilerfi'ormance. Once we have adjusted the historical results (see Step 3), we are ready to forecast

, ture results.

In ~odule 11, we ex~lain how to project financial statements. The forecasting process dis~mssed m Module 11 apph~s to c~e_dit analysis as well as to equity valuation. In particular, proOeted cash flows are especially cnt1cal because a company must have sufficient cash in the future

t0 repay ~ebts as the~ mature and to service those debts along the way. The projected financials

h@l!lld adjust the cap.ital structure to reflect anticipated future debt retirements as they come due

~l'er ~he forecast honzo~. Once .we have the projected financials, we can compute the ratios we

mescnbed above (regarding profitability, liquidit), solvency, and coverage) and evaluate changes

!!trends.

Home Depot Solvency Ratios

ID -MODULE REVIEW 2

eo'f~.r to the fiscal 2011 income statement and balance sheet of Lowe's Companies, Inc. , below.

1.3

1.1

0.9

0.7

Net sales .... . ......................... . . . .. .. ....... .

Cost of sales ... ... ........ . ............ . .... . . .. . .... .

0.5

0 .3

20_0_9_

0 1 "----2-0 0_8_ __,:....__

2_0_1_0 _ _,__ _20

_ 11_ __,

___..._ _

Total debt-to-equity A drawback of the liabilities-to-equity ratio is that it does not distinguish

between operating creditors (such as accounts payable) and debt obligations. We can refine our

analysis with a solvency ratio such as follows:

Long-term debt including current portion

Total debt-to-equity =

S

tockholders' equity

+ Short-term debt

Gross margin .. ....... ..................... . . .. . . ....

Selling, general and administrative expense ... ........ .....

Depreciation .. .... . . ... . ................... .... ......

Interest ... . .. .... . . . . .. .. . . .. . .. . .. .. .. . ... . ..... . .

$48,815

31,663

.

.

.

.

17, 152

12,006

1.586

332

Total expenses . .... .. . . .... . .. . . . . ... . . . . . ....... . ... .

13,924

Pretax earnings . .. .. .. . . . . ... . ....... . . .... . .. .. . .. .. .

Income tax provision . .......................... .. ..... .

3 ,228

1,218

Net earnings ..... . .. . .................. . ... . . . .. . .... .

$ 2,010

4-18

4-19

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

(In millions, except par value)

Module 4 I Credit Risk Analysis and Interpretation

LOWE'S COMPANIES, INC.

Balance Slleet

Januar;y 28, 2011

Assets

Cash and cash equivalents . . . ..... . ....... . .. . . . . .. . .

Short-term investments . ..... ..... . .......... . ... . .

Merchandise inventory, net ................... . . ... .

Deferred income taxes, net ...... . ...................

Other current assets ... .... ........ . .. . ..... . .. .. . ..

Total current assets .. ....... . .. .. ... . .. . .. . .. . ..... .

Property, less accumulated depreciation ... . ...... . .. . . . .

Long-term investments .. .. . .. . ...... .. .. . ... ... .. .. .

Other assets .. . . ... .... ....... . . . . .. . . .. .. . . .... .

Total assets .... . . . . .. . .. ... .. ..........

652

471

8,321

193

330

9,967

22,089

1,008

635

--$33,699

$

Liabilities and Shareholders' Equity

Current maturities of long-term debt ............. ...... .

Accounts payable . ...... . ... ..................... .. .

Accrued compensation and employee benefits .... .. ... . . .

Deferred revenue . . ....... .... .. ........

Other current liabilities .... . . . .. . . ... . .. . . . . .. ... ....

Total current liabilities .. .. . . ........ . .. . . . .. ... . .. . . .

Long-term debt, excluding current maturities ... . .. .. ... . .

Deferred income taxes, net . .... .... . .. . .. .........

Deferred revenue-extended protection plans . . . . ... .... .

Other liabilities .. . .. . ... . . .. . ............. . . . .

Total liabilities ..... . . .. . .. . . ............ . . . ..

Shareholders' equity

Preferred stock-$5 par value, none issued ... . .... ..... .

Common stock-$.50 par value; shares issued and

outstanding, 2011: 1,354; 2010: 1,459 ................ .

Capital in excess of par value . ... .. .. . .. . .... . .. . .... .

Retained earnings ... . . . ... . ............ .. .

Accumulated other comprehensive income .. . . . .. . .. . .. . .

Total shareholders' equity .... . . . . .......... .. ..... . .

Total liabilities and shareholders' equity ......... ... . .. .

Januar:y 29, 2010

632

425

8,249

208

218

9,732

22,499

277

497

--$33,005

$

---

The solution is on page 4-46.

36

4,351

667

707

1,358

7,119

6,537

467

631

833

15,587

677

11

17,371

53

552

4,287

577

683

1,256

7,355

4,528

598

549

906

13,936

729

6

18,307

27

18,112

19,069

$33,699

$33,005

---

Required

.

, C

I t r~t

Compute the following liquidity, solvency, and coverage ratios for Lowes ompames. n ~rp

and assess these ratios for Lowe's relative to those previously computed for Home Depot I? ?un

text. For 2011, Lowe's statement of cash flows reported cash fro~ operation~ of $3,852 m1llmn

and capital expenditures of $1,329 million . Assume Lowe's margmal tax rate is 35%.

1. Return on net operating assets

2. Return on equity

3. Times interest earned

4. EBITDA coverage

5. Operating cash flow to debt

6. Free cash flow to debt

7. Current ratio

8. Quick ratio

9. Liabilities-to-equity ratio

10. Total debt-to-equity ratio

'

t the main purpose of credit risk analysis is to quantify potential credit losses so that

\;ions are made with full information. Expected credit losses are the product of two

, e ehance of default and the size of the loss given a default. The previous section di sto analyze financial information to determine the cha nce of default. In this section,

eir the factors that affect the amount that could be lost if the company defaulted on its

s 11eferred to as loss given default .

a oompany defaults on its obligations (such as failing to make payments or violating

errants), creditors seek to claim the remaining assets owed. A creditor's potential loss

,s <.'Jn the priority of the claim compared with all other existing claims. Laws and private

1

t>S <!letermine the order of repayment among all the creditors . Companies must repay

cllai!S first and the U .S . Bankruptcy Code specifies the priority of other claims . If a

, artifi.5; is n default, it is likely that it has fully drawn on lines of credit. This means that it has

",e !l!J!S t: raise additional cash . For low priority claims (called junior claims), a conservative

~ t (:}St~mati~g t_he potenti~I loss ~ould be to assume t_hat the entire amount :"ill be lost.

,e ~a to minimize potential loss 1s to structure credit terms for the loan m advance.

~Jte.Gliiv terms include (1) credit limits, (2) collateral, (3) repayment terms, and (4) cov1!'.@ imit the loss in the event of default. This section focuses on each of these four credit

t i!S important to understand the relation between the likelihood of default (as assessed

. a:nal sis above) and credit terms: the higher the chance of default , the stricter the credit

ii f~nd0_r will impose. For example , if long-term solvency is in question , a lender might

re epayment terms so that the loan is repaid in the short term. However, there is a trade' e emder does not want to set credit terms so strict that the terms themselves cause the

nt Clefault. In general , trade creditors, banks, and other lenders follow standard operat Ge~u)1eS that provide guidelines on credit terms.

Rating

>10% and < 30%

2 30% and < 50%

LGD4 . . .. ... .

LGD5 ..... . . .

LGD6 . .... . . .

Loss range

2 50% and > 70%

> 70% and < 90%

2 90% and s::100%

A credit limit is the maximum that a creditor will allow a customer to owe at any

1111e . These limits are set based on the lender 's experience with similar borrowers as well

ifi credit analysis. Some view a credit limit as the maximum amount that a creditor

11

im:e, to lose to the customer. By carefully setting credit limits, creditors can minimize their

lilen~vent of default, which limits credit risk.

ra! e credit r commonly set low credit limits for new customers and higher limits for cuss 'th uepayment histories. The Bankruptcy Abuse and Consumer Protection Act (2005)

. ~rotection to ordinary trade creditors. The Act provides that accounts payable for

_Qlfled lo a customer within 20 days before the bankruptcy have a higher priority for paylfl,ISI neduces the size of a loss but trade creditors must monitor its customers for signs of