Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Research Methodology

Caricato da

samwelCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research Methodology

Caricato da

samwelCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research Methodology

Formulating a research problem in qualitative research

The difference in qualitative and quantitative studies starts with the way you formulate your

research problem. In quantitative research you strive to be as specific as possible, attempt to

narrow the magnitude of your study and develop a framework within which you confine your

search. On the other hand, in qualitative research, this specificity in scope, methods and

framework is almost completely ignored. You strive to maintain flexibility, openness and

freedom to include any new ideas or exclude any aspect that you initially included but later

consider not to be relevant. At the initial stage you only identify the main thrust of your study

and some specific aspects which you want to find out about.

Qualitative research primarily employs inductive reasoning. In contrast to quantitative research,

where a research problem is stated before data collection, in qualitative research the problem is

reformulated several times after you have begun the data collection. The research problem as

well as data collection strategies are reformulated as necessary throughout data collection either

to acquire the totality of a phenomenon or to select certain aspects for greater in-depth study.

This flexibility and freedom, though providing you with certain advantages, can also create

problems in terms of comparability of the information gathered. It is possible that your areas of

search may become markedly different during the preliminary and final stages of data gathering.

During the initial developmental phase, many researchers produce a framework of reminders (a

conceptual framework of enquiry) to ensure that key issues/aspects are covered during

discussions with the respondents. As the study progresses, if needs be, issues or themes are

added to this framework. This is not a list of questions but reminders that are only used if for

some reason the interaction with respondents lacks discussion.

Collecting the data

There are several ways of collecting the appropriate data which differ considerably in context of

money costs, time and other resources at the disposal of the researcher. Primary data can be

collected either through experiment or through survey. If the researcher conducts an experiment,

he observes some quantitative measurements, or the data, with the help of which he examines the

truth contained in his hypothesis. But in the case of a survey, data can be collected by any one or

more of the following ways:

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 1

Research Methodology

1) By observation: This method implies the collection of information by way of

investigators own observation, without interviewing the respondents. The information

obtained relates to what is currently happening and is not complicated by either the past

behaviour or future intentions or attitudes of respondents. This method is no doubt an

expensive method and the information provided by this method is also very limited. As

such this method is not suitable in inquiries where large samples are concerned.

2) Through personal interview: The investigator follows a rigid procedure and seeks

answers to a set of pre-conceived questions through personal interviews. This method of

collecting data is usually carried out in a structured way where output depends upon the

ability of the interviewer to a large extent.

3) Through telephone interviews: This method of collecting information involves

contacting the respondents on telephone itself. This is not a very widely used method but

it plays an important role in industrial surveys in developed regions, particularly, when

the survey has to be accomplished in a very limited time.

4) By mailing of questionnaires: Questionnaires are mailed to the respondents with a

request to return after completing the same. It is the most extensively used method in

various economic and business surveys. Before applying this method, usually a Pilot

Study for testing the questionnaire is conducted to reveal the weaknesses, if any, of the

questionnaire. Questionnaires to be used must be prepared very carefully so that it may

prove to be effective in collecting the relevant information.

The researcher should select one of these methods of collecting the data taking into consideration

the nature of investigation, objective and scope of the inquiry, financial resources, available time

and the desired degree of accuracy. Though he should pay attention to all these factors but much

depends upon the ability and experience of the researcher.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 2

Research Methodology

LITERATURE REVIEW

One of the essential preliminary tasks when you undertake a research study is to go through the

existing literature in order to acquaint yourself with the available body of knowledge in your area

of interest. Reviewing the literature can be time consuming, daunting and frustrating, but it is

also rewarding. The literature review is an integral part of the research process and makes a

valuable contribution to almost every operational step.

In the initial stages of research it helps you to establish the theoretical roots of your study, clarify

your ideas and develop your research methodology. Later in the process, the literature review

serves to enhance and consolidate your own knowledge base and helps you to integrate your

findings with the existing body of knowledge. Since an important responsibility in research is to

compare your findings with those of others, it is here that the literature review plays an

extremely important role. During the write-up of your report it helps you to integrate your

findings with existing knowledge that is, to either support or contradict earlier research.

In summary, a literature review has the following functions:

(i) It provides a theoretical background to your study.

(ii) It helps you establish the links between what you are proposing to examine and what has

already been studied.

(iii)It enables you to show how your findings have contributed to the existing body of

knowledge in your profession. It helps you to integrate your research findings into the

existing body of knowledge.

In relation to your own study, the literature review can help in four ways. It can:

(a) Bring clarity and focus to your research problem

(b) Improve your research methodology

(c) Broaden your knowledge base in your research area

(d) Contextualise your findings

There are four steps involved in conducting a literature review:

(i) Searching for the existing literature in your area of study.

(ii) Reviewing the selected literature.

(iii)Developing a theoretical framework.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 3

Research Methodology

(iv) Developing a conceptual framework.

1. Searching for the existing literature

To search effectively for the literature in your field of enquiry, it is imperative that you have at

least some idea of the broad subject area and of the problem you wish to investigate, in order to

set parameters for your search. Next, compile a bibliography for this broad area. There are three

sources that you can use to prepare a bibliography:

1) books;

2) journals;

3) the Internet

(a) Books

Though books are a central part of any bibliography, they have their disadvantages as well as

advantages. The main advantage is that the material published in books is usually important and

of good quality, and the findings are integrated with other research to form a coherent body of

knowledge. The main disadvantage is that the material is not completely up to date, as it can

take a few years between the completion of a work and its publication in the form of a book.

The best way to search for a book is to look at your library catalogues. Use the subject catalogue

or keywords option to search for books in your area of interest. Narrow the subject area searched

by selecting the appropriate keywords. When you have selected 1015 books that you think are

appropriate for your topic, examine the bibliography of each one carefully to identifying the

books common to several of them for inclusion into your reading list. Prepare a final list of

books that you consider essential reading and locate these books in your library or borrow them

from other sources.

(b) Journals

Journals provide you with the most up-to-date information and you should select as many

journals relating to your research as you possibly can. As with books, you need to prepare a list

of the journals you want to examine for identifying the literature relevant to your study. This can

be done in a number of ways. You can:

(i) locate the hard copies of the journals that are appropriate to your study

(ii) look at citation or abstract indices to identify and/or read the abstracts of such articles

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 4

Research Methodology

(iii)search electronic databases

In most libraries, information on books, journals and abstracts is stored on computers. In each

case the information is classified by subject, author and title. You may also have the keywords

option (author/keyword; title/keyword; subject/keyword; expert/keyword; or just keywords).

What system you use depends upon what is available in your library and what you are familiar

with. There are specially prepared electronic databases in a number of disciplines. These can also

be helpful in preparing a bibliography. For example, most libraries carry the electronic databases.

Select the database most appropriate to your area of study to see if there are any useful

references.

(c) The Internet

In almost every academic discipline and professional field, the Internet has become an important

tool for finding published literature. Through an Internet search you can identify published

material in books, journals and other sources with immense ease and speed. An Internet search

basically identifies all material in the database of a search engine that contains the keywords you

specify, either individually or in combination.

2. Reviewing the selected literature

Now that you have identified several books and articles as useful, the next step is to start reading

them critically to pull together themes and issues that are of relevance to your study. Once you

develop a rough framework, books and articles, using a separate sheet of paper for each theme of

the framework so far developed. As you read further, go on slotting the information where it

logically belongs under the themes so far developed. While going through the literature you

should carefully and critically examine it with respect to the following aspects:

(i) Note whether the knowledge relevant to your theoretical framework has been confirmed

beyond doubt.

(ii) Note the theories put forward, the criticisms of these and their basis, the methodologies

adopted (study design, sample size and its characteristics, measurement procedures, etc.)

and the criticisms of them.

(iii)Examine to what extent the findings can be generalised to other situations.

(iv) Notice where there are significant differences of opinion among researchers and give

your opinion about the validity of these differences.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 5

Research Methodology

(v) Ascertain the areas in which little or nothing is known the gaps that exist in the body of

knowledge.

3) Developing a theoretical framework

As you start reading the literature, you will soon discover that the problem you wish to

investigate has its roots in a number of theories that have been developed from different

perspectives. The information obtained from different books and journals now needs to be sorted

under the main themes and theories, highlighting agreements and disagreements among the

authors and identifying the unanswered questions or gaps. You will also realise that the literature

deals with a number of aspects that have a direct or indirect bearing on your research topic. Use

these aspects as a basis for developing your theoretical framework. Unless you review the

literature in relation to this framework, you will not be able to develop a focus in your literature

search: that is, your theoretical framework provides you with a guide as you read.

This brings us to the paradox mentioned previously: until you go through the literature you

cannot develop a theoretical framework, and until you have developed a theoretical framework

you cannot effectively review the literature. The solution is to read some of the literature and

then attempt to develop a framework, even a loose one, within which you can organise the rest of

the literature you read. Without a framework, you will get bogged down in a great deal of

unnecessary reading and note-taking that may not be relevant to your study.

4) Developing a conceptual framework

The conceptual framework is the basis of your research problem. It stems from the theoretical

framework and usually focuses on the section(s) which become the basis of your study. Whereas

the theoretical framework consists of the theories or issues in which your study is embedded, the

conceptual framework describes the aspects you selected from the theoretical framework to

become the basis of your enquiry. Hence the conceptual framework grows out of the theoretical

framework and relates to the specific research problem.

Writing about the literature reviewed

Now, all that remains to be done is to write about the literature you have reviewed. The two

broad functions of a literature review are (1) to provide a theoretical background to your study

and (2) to enable you to contextualise your findings in relation to the existing body of knowledge

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 6

Research Methodology

in addition to refining your methodology. In order to fulfill the first purpose, you should identify

and describe various theories relevant to your field; and specify gaps in existing knowledge in

the area, recent advances in the area of study, current trends and so on. In order to comply with

the second function you should integrate the results from your study with specific and relevant

findings from the existing literature by comparing the two for confirmation or contradiction.

Note that at this stage you can only accomplish the first function of the literature review, to

provide a theoretical background to your study. For the second function, the contextualisation of

the findings, you have to wait till you are at the research report writing stage.

While reading the literature for theoretical background of your study, you will realise that certain

themes have emerged. List the main ones, converting them into subheadings. These subheadings

should be precise, descriptive of the theme in question and follow a logical progression. Now,

under each subheading, record the main findings with respect to the theme in question (thematic

writing), highlighting the reasons for and against an argument if they exist, and identifying gaps

and issues.

The second broad function of the literature review contextualising the findings of your study

requires you to compare very systematically your findings with those made by others. Quote

from these studies to show how your findings contradict, confirm or add to them. It places your

findings in the context of what others have found out providing complete reference in an

acceptable format. This function is undertaken when writing about your findings after analysis of

your data.

Development of working hypotheses

After extensive literature survey, researcher should state in clear terms the working hypothesis or

hypotheses. Working hypothesis is tentative assumption made in order to draw out and test its

logical or empirical consequences. As such the manner in which research hypotheses are

developed is particularly important since they provide the focal point for research. They also

affect the manner in which tests must be conducted in the analysis of data and indirectly the

quality of data which is required for the analysis. In most types of research, the development of

working hypothesis plays an important role.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 7

Research Methodology

Hypothesis should be very specific and limited to the piece of research in hand because it has to

be tested. The role of the hypothesis is to guide the researcher by delimiting the area of research

and to keep him on the right track. It sharpens his thinking and focuses attention on the more

important facets of the problem. It also indicates the type of data required and the type of

methods of data analysis to be used.

To develop a working hypothesis, the following approach is used:

1) Discussions with colleagues and experts about the problem, its origin and the objectives

in seeking a solution;

2) Examination of data and records, if available, concerning the problem for possible trends,

peculiarities and other clues;

3) Review of similar studies in the area or of the studies on similar problems; and

4) Exploratory personal investigation which involves original field interviews on a limited

scale with interested parties and individuals with a view to secure greater insight into the

practical aspects of the problem.

Working hypotheses are more useful when stated in precise and clearly defined terms.

Occasionally we may encounter a problem where we do not need working hypotheses, especially

in the case of exploratory or formulative researches which do not aim at testing the hypothesis.

But as a general rule, specification of working hypotheses in another basic step of the research

process in most research problems.

Preparing the research design

The research problem having been formulated in clear cut terms, the researcher will be required

to prepare a research design, i.e., he will have to state the conceptual structure within which

research would be conducted. The preparation of such a design facilitates research to be as

efficient as possible yielding maximal information. In other words, the function of research

design is to provide for the collection of relevant evidence with minimal expenditure of effort,

time and money. But how all these can be achieved depends mainly on the research purpose.

Research purposes may be grouped into four categories,

1)

Exploration,

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 8

Research Methodology

2)

Description,

3)

Diagnosis, and

4)

Experimentation.

A flexible research design which provides opportunity for considering many different aspects of

a problem is considered appropriate if the purpose of the research study is that of exploration.

But when the purpose happens to be an accurate description of a situation or of an association

between variables, the suitable design will be one that minimises bias and maximizes the

reliability of the data collected and analysed.

There are several research designs, such as, experimental and non-experimental hypothesis

testing. Experimental designs can be either informal designs (such as before-and-after without

control, after-only with control, before-and-after with control) or formal designs (such as

completely randomized design, randomized block design, Latin square design, simple and

complex factorial designs), out of which the researcher must select one for his own project. The

preparation of the research design, appropriate for a particular research problem, involves usually

the consideration of the following:

1) the means of obtaining the information;

2) the availability and skills of the researcher and his staff (if any);

3) explanation of the way in which selected means of obtaining information will be

organized

4) and the reasoning leading to the selection;

5) the time available for research; and

6) the cost factor relating to research, i.e., the finance available for the purpose

The study population

Every study has a study population, from whom the required information to find answers to the

research questions is obtained. As you narrow the research problem, similarly you need to decide

very specifically and clearly who constitutes your study population, in order to select the

appropriate respondents. Suppose you have designed a study to ascertain the needs of young

people living in a community. In terms of the study population, one of the first questions you

need to answer is: Who do I consider to be a young person? You need to decide, in measurable

terms, which age group your respondents should come from. Is it those between 15 and 18, 15

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 9

Research Methodology

and 20 or 15 and 25 years of age? Or you may be interested in some other age group. You need

to decide this before undertaking your research journey. Having decided the age group that

constitutes your young person, the next question you need to consider is whether you want to

select young people of either gender or confine the study to one only. In addition, there is

another dimension to consider: that is, what constitutes the community? Which geographical

area(s) or ethnic background should I select my respondents from? Let us take another example.

Suppose you want to find out the settlement process of immigrants.

As a part of identifying your study population, you need to decide who you would consider an

immigrant. Is it a person who immigrated 5, 10, 15 or 20 years ago? You also need to consider

the countries from where the immigrants come. Will you select your respondents irrespective of

the country of origin or select only those who have come from a specific country? In a way you

need to narrow your definition of the study population as you have done with your research

problem. These issues are discussed in greater depth under Establishing operational definitions

following this section. In quantitative research, you need to narrow both the research problem

and the study population and make them as specific as possible so that you and your readers are

clear about them. In qualitative research, reflecting the exploratory philosophical base of the

approach, both the study population and the research problem should remain loose and flexible

to ensure the freedom necessary to obtain varied and rich data if a situation emerges.

SAMPLING

The researcher must decide the way of selecting a sample or what is popularly known as the

sample design. In other words, a sample design is a definite plan determined before any data are

actually collected for obtaining a sample from a given population. Samples can be either

probability samples or non-probability samples. With probability samples each element has a

known probability of being included in the sample but the non-probability samples do not allow

the researcher to determine this probability. Probability samples are those based on simple

random sampling, systematic sampling, stratified sampling, cluster/area sampling whereas nonprobability samples are those based on convenience sampling, judgement sampling and quota

sampling techniques. A brief mention of the important sample designs is as follows:

1) Deliberate sampling: Deliberate sampling is also known as purposive or non-probability

sampling. This sampling method involves purposive or deliberate selection of particular

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 10

Research Methodology

units of the population for constituting a sample. When population elements are selected

for inclusion in the sample based on the ease of access, it can be called convenience

sampling. If a researcher wishes to secure data from, say, petrol buyers, he may select a

fixed number of petrol stations and may conduct interviews at these stations. This would

be an example of convenience sample of petrol buyers. At times such a procedure may

give very biased results particularly when the population is not homogeneous. On the

other hand, in judgement sampling the researchers judgement is used for selecting items

which he considers as representative of the population. For example, a judgement sample

of college students might be taken to secure reactions to a new method of teaching.

Judgement sampling is used quite frequently in qualitative research where the desire

happens to be to develop hypotheses rather than to generalise to larger populations.

2) Simple random sampling: This type of sampling is also known as chance sampling or

probability sampling where each and every item in the population has an equal chance of

inclusion in the sample and each one of the possible samples has the same probability of

being selected. For example, if we have to select a sample of 300 items from a population

of 15,000 items, then we can put the names or numbers of all the 15,000 items on slips of

paper and conduct a lottery. Using the random number tables is another method of

random sampling. To select the sample, each item is assigned a number from 1 to 15,000.

Then, 300 random numbers are selected from the table. To do this we select some

random starting point and then a systematic pattern is used in proceeding through the

table. We might start in the 4th row, second column and proceed down the column to the

bottom of the table and then move to the top of the next column to the right. Since the

numbers were placed in the table in a completely random fashion, the resulting sample is

random. This procedure gives each item an equal probability of being selected.

3) Systematic sampling: In some instances the most practical way of sampling is to select

every 15th name on a list, every 10th house on one side of a street and so on. Sampling of

this type is known as systematic sampling. An element of randomness is usually

introduced into this kind of sampling by using random numbers to pick up the unit with

which to start. This procedure is useful when sampling frame is available in the form of a

list. In such a design the selection process starts by picking some random point in the list

and then every nth element is selected until the desired number is secured.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 11

Research Methodology

4) Stratified sampling: If the population from which a sample is to be drawn does not

constitute a homogeneous group, then stratified sampling technique is applied so as to

obtain a representative sample. In this technique, the population is stratified into a

number of non-overlapping sub-populations or strata and sample items are selected from

each stratum. If the items selected from each stratum is based on simple random sampling

the entire procedure, first stratification and then simple random sampling, is known as

stratified random sampling.

5) Quota sampling: In stratified sampling the cost of taking random samples from

individual strata is often so expensive that interviewers are simply given quota to be filled

from different strata, the actual selection of items for sample being left to the

interviewers judgement. This is called quota sampling. The size of the quota for each

stratum is generally proportionate to the size of that stratum in the population. Quota

sampling is thus an important form of non-probability sampling. Quota samples generally

happen to be judgement samples rather than random samples.

6) Cluster sampling and area sampling: Cluster sampling involves grouping the

population and then selecting the groups or the clusters rather than individual elements

for inclusion in the sample. Suppose some departmental store wishes to sample its credit

card holders. It has issued its cards to 15,000 customers. The sample size is to be kept say

450. For cluster sampling this list of 15,000 card holders could be formed into 100

clusters of 150 card holders each. Three clusters might then be selected for the sample

randomly. The clustering approach can make the sampling procedure relatively easier and

increase the efficiency of field work, especially in the case of personal interviews.

Area sampling is quite close to cluster sampling and is often talked about when the total

geographical area of interest happens to be big one. Under area sampling we first divide

the total area into a number of smaller non-overlapping areas, generally called

geographical clusters, then a number of these smaller areas are randomly selected, and all

units in these small areas are included in the sample. Area sampling is especially helpful

where we do not have the list of the population concerned. It also makes the field

interviewing more efficient since interviewer can do many interviews at each location.

7) Multi-stage sampling: This is a further development of the idea of cluster sampling.

This technique is meant for big inquiries extending to a considerably large geographical

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 12

Research Methodology

area like an entire country. Under multi-stage sampling the first stage may be to select

large primary sampling units such as states, then districts, then towns and finally certain

families within towns. If the technique of random-sampling is applied at all stages, the

sampling procedure is described as multi-stage random sampling.

OPERATIONAL DEFINITION OF VARIABLES

In defining the problem you may use certain words or items that are difficult to measure and/or

the understanding of which may vary from respondent to respondent. In a research study it is

important to develop, define or establish a set of rules, indicators or yardsticks in order to

establish clearly the meaning of such words/items. It is sometimes also important to define

clearly the study population from which you need to obtain the required information. When you

define concepts that you plan to use either in your research problem and/or in identifying the

study population in a measurable form, they are called working definitions or operational

definitions. You must understand that these working definitions that you develop are only for the

purpose of your study and could be quite different to legal definitions, or those used by others.

As the understanding of concepts can vary markedly from person to person, your working

definitions will inform your readers what exactly you mean by the concepts that you have used in

your study.

The following example studies help to explain this. The main objectives are:

1. To find out the number of children living below the poverty line in Australia.

2. To ascertain the impact of immigration on family roles among immigrants.

3. To measure the effectiveness of a retraining programme designed to help

young people.

Although these objectives clearly state the main thrust of the studies, they are not specific in

terms of the main variables to be studied and the study populations. You cannot count the

number of children living below the poverty line until you decide what constitutes the poverty

line and how to determine it; you cannot find out the impact of immigration on family roles

unless you identify which roles constitute family roles; and you cannot measure effectiveness

until you define what effectiveness is. On the other hand, it is equally important to decide exactly

what you mean by children, immigrants or young. Up to what age will you consider a

person to be a child (i.e. 5, 10, 15 or 18)? Who would you consider young? A person who isn15

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 13

Research Methodology

years of age, 20, 25 or 30? Who would you consider to be an immigrant? A person who

immigrated 40, 20 or 5 years ago? In addition, are you going to consider immigrants from every

country or only a few? In many cases you need to develop operational definitions for the

variables and concepts you are studying and for the population that becomes the source of the

information for your study.

In a research study you need to define these clearly in order to avoid ambiguity and confusion.

This is achieved through the process of developing operational/working definitions. You need to

develop operational definitions for the major concepts you are using in your study and develop a

framework for the study population enabling you to select appropriate respondents.

Operational definitions give an operational meaning to the study population and the concepts

used. It is only through making your procedures explicit that you can validly describe, explain,

verify and test. It is important to remember that there are no rules for deciding if an operational

definition is valid. Your arguments must convince others about the appropriateness of your

definitions.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 14

Research Methodology

MEASUREMENT AND SCALING TECHNIQUES

In our daily life we are said to measure when we use some yardstick to determine weight, height,

or some other feature of a physical object. We also measure when we judge how well we like a

song, a painting or the personalities of our friends. We, thus, measure physical objects as well as

abstract concepts. By measurement we mean the process of assigning numbers to objects or

observations, the level of measurement being a function of the rules under which the numbers are

assigned.

Classification of measurement scales

The most widely used classification of measurement scales are:

(a) nominal scale

(b) ordinal scale

(c) interval scale

(d) ratio scale

(i) Nominal scale is simply a system of assigning number symbols to events in order to label

them. The usual example of this is the assignment of numbers of basketball players in order

to identify them. Such numbers cannot be considered to be associated with an ordered scale

for their order is of no consequence; the numbers are just convenient labels for the particular

class of events and as such have no quantitative value. Nominal scales provide convenient

ways of keeping track of people, objects and events. One cannot do much with the numbers

involved. For example, one cannot usefully average the numbers on the back of a group of

football players and come up with a meaningful value. Neither can one usefully compare the

numbers assigned to one group with the numbers assigned to another. The counting of

members in each group is the only possible arithmetic operation when a nominal scale is

employed. Accordingly, we are restricted to use mode as the measure of central tendency.

There is no generally used measure of dispersion for nominal scales. Chi-square test is the

most common test of statistical significance that can be utilized, and for the measures of

correlation, the contingency coefficient can be worked out. A nominal scale simply describes

differences between things by assigning them to categories. Nominal data are, thus, counted

data.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 15

Research Methodology

(ii) Ordinal scale: The ordinal scale places events in order, but there is no attempt to make the

intervals of the scale equal in terms of some rule. Rank orders represent ordinal scales and

are frequently used in research relating to qualitative phenomena. A students rank in his

graduation class involves the use of an ordinal scale. One has to be very careful in making

statement about scores based on ordinal scales. For instance, if Johns position in his class is

10 and Peters position is 40, it cannot be said that Johns position is four times as good as

that of Peter. The statement would make no sense at all. Ordinal scales only permit the

ranking of items from highest to lowest. Ordinal measures have no absolute values, and the

real differences between adjacent ranks may not be equal. All that can be said is that one

person is higher or lower on the scale than another, but more precise comparisons cannot be

made.

Thus, the use of an ordinal scale implies a statement of greater than or less than without

our being able to state how much greater or less. The real difference between ranks 1 and 2

may be more or less than the difference between ranks 5 and 6. Since the numbers of this

scale have only a rank meaning, the appropriate measure of central tendency is the median. A

percentile or quartile measure is used for measuring dispersion. Correlations are restricted to

various rank order methods. Measures of statistical significance are restricted to the nonparametric methods.

(iii)Interval scale: In the case of interval scale, the intervals are adjusted in terms of some rule

that has been established as a basis for making the units equal. The units are equal only in so

far as one accepts the assumptions on which the rule is based. Interval scales can have an

arbitrary zero, but it is not possible to determine for them what may be called an absolute

zero or the unique origin. The primary limitation of the interval scale is the lack of a true

zero; it does not have the capacity to measure the complete absence of a trait or

characteristic. The Fahrenheit scale is an example of an interval scale and shows similarities

in what one can and cannot do with it. One can say that an increase in temperature from 30

to 40 involves the same increase in temperature as an increase from 60 to 70, but one

cannot say that the temperature of 60 is twice as warm as the temperature of 30 because

both numbers are dependent on the fact that the zero on the scale is set arbitrarily at the

temperature of the freezing point of water. The ratio of the two temperatures, 30 and 60,

means nothing because zero is an arbitrary point. This means that while no mathematical

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 16

Research Methodology

operation can be performed on the readings, it can be performed on the differences between

readings. For example, if the difference in temperature between two objects, A and B, is

15C and the difference in temperature between two other objects, C and D, is 45C, you can

say that the difference in temperature between C and D is three times greater than that

between A and B.

Interval scales provide more powerful measurement than ordinal scales for interval scale also

incorporates the concept of equality of interval. As such more powerful statistical measures

can be used with interval scales. Mean is the appropriate measure of central tendency, while

standard deviation is the most widely used measure of dispersion. Product moment

correlation techniques are appropriate and the generally used tests for statistical significance

are the t test and F test.

(iv) Ratio scale: Ratio scales have an absolute or true zero of measurement. The term absolute

zero is not as precise as it was once believed to be. We can conceive of an absolute zero of

length and similarly we can conceive of an absolute zero of time. For example, the zero point

on a centimeter scale indicates the complete absence of length or height. But an absolute zero

of temperature is theoretically unobtainable and it remains a concept existing only in the

scientists mind. The number of minor traffic-rule violations and the number of incorrect

letters in a page of type script represent scores on ratio scales. Both these scales have

absolute zeros and as such all minor traffic violations and all typing errors can be assumed to

be equal in significance. With ratio scales involved one can make statements like Johns

typing performance was twice as good as that of Peter. The ratio involved does have

significance and facilitates a kind of comparison which is not possible in case of an interval

scale.

Ratio scale represents the actual amounts of variables. Measures of physical dimensions such

as weight, height, distance, etc. are examples. Generally, all statistical techniques are usable

with ratio scales and all manipulations that one can carry out with real numbers can also be

carried out with ratio scale values. Multiplication and division can be used with this scale but

not with other scales mentioned above. Geometric and harmonic means can be used as

measures of central tendency and coefficients of variation may also be calculated.

Thus, proceeding from the nominal scale (the least precise type of scale) to ratio scale (the

most precise), relevant information is obtained increasingly. If the nature of the variables

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 17

Research Methodology

permits, the researcher should use the scale that provides the most precise description.

Researchers in physical sciences have the advantage to describe variables in ratio scale form

but the behavioural sciences are generally limited to describe variables in interval scale form,

a less precise type of measurement.

Sources of Error in Measurement

Measurement should be precise and unambiguous in an ideal research study. This objective,

however, is often not met with in entirety. As such the researcher must be aware about the

sources of error in measurement. The following are the possible sources of error in measurement.

(i) Respondent: At times the respondent may be reluctant to express strong negative feelings or

it is just possible that he may have very little knowledge but may not admit his ignorance. All

this reluctance is likely to result in an interview of guesses. Transient factors like fatigue,

boredom, anxiety, etc. may limit the ability of the respondent to respond accurately and fully.

(ii) Situation: Any condition which places a strain on interview can have serious effects on the

interviewer-respondent rapport. If the respondent feels that anonymity is not assured, he may

be reluctant to express certain feelings.

(iii)Measurer: The interviewer can distort responses by rewording or reordering questions. His

behaviour, style and looks may encourage or discourage certain replies from respondents.

Errors may also creep in because of incorrect coding, faulty tabulation and/or statistical

calculations, particularly in the data-analysis stage.

(iv) Instrument: The use of complex words, beyond the comprehension of the respondent,

ambiguous meanings, poor printing, inadequate space for replies, response choice omissions,

etc. are a few things that make the measuring instrument defective and may result in

measurement errors. Another type of instrument deficiency is the poor sampling of the

population of items of concern.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 18

Research Methodology

Tests of Sound Measurement

Sound measurement must meet the tests of validity, reliability and practicality. In fact, these are

the three major considerations one should use in evaluating a measurement tool. Validity refers

to the extent to which a test measures what we actually wish to measure. Reliability has to do

with the accuracy and precision of a measurement procedure ... Practicality is concerned with a

wide range of factors of economy, convenience, and interpretability ...

1. Test of Validity

Validity is the most critical criterion and indicates the degree to which an instrument measures

what it is supposed to measure. In other words, validity is the extent to which differences found

with a measuring instrument reflect true differences among those being tested. There are three

types of validity:

(i) Content validity is the extent to which a measuring instrument provides adequate coverage

of the topic under study. If the instrument contains a representative sample of the

population, the content validity is good. Its determination is primarily judgemental and

intuitive.

(ii) Criterion-related validity relates to our ability to predict some outcome or estimate the

existence of some current condition. This form of validity reflects the success of measures

used for some empirical estimating purpose. The concerned criterion must possess the

following qualities:

Relevance: A criterion is relevant if it is defined in terms we judge to be the proper

measure.

Freedom from bias: Freedom from bias is attained when the criterion gives each subject

an equal opportunity to score well.

Reliability: A reliable criterion is stable or reproducible.

Availability: The information specified by the criterion must be available.

In fact, a Criterion-related validity is a broad term that actually refers to (i) Predictive validity

which is the usefulness of a test in predicting some future performance and (ii) Concurrent

validity which refers to the usefulness of a test in closely relating to other measures of known

validity. Criterion-related validity is expressed as the coefficient of correlation between test

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 19

Research Methodology

scores and some measure of future performance or between test scores and scores on another

measure of known validity.

(iii)Construct validity is the most complex and abstract. A measure is said to possess construct

validity to the degree that it confirms to predicted correlations with other theoretical

propositions. Construct validity is the degree to which scores on a test can be accounted for

by the explanatory constructs of a sound theory. For determining construct validity, we

associate a set of other propositions with the results received from using our measurement

instrument. If measurements on our devised scale correlate in a predicted way with these

other propositions, we can conclude that there is some construct validity.

2. Test of Reliability

The test of reliability is another important test of sound measurement. A measuring instrument is

reliable if it provides consistent results. Reliable measuring instrument does contribute to

validity, but a reliable instrument need not be a valid instrument. For instance, a scale that

consistently overweighs objects by five kgs., is a reliable scale, but it does not give a valid

measure of weight. But the other way is not true i.e., a valid instrument is always reliable.

Accordingly reliability is not as valuable as validity, but it is easier to assess reliability in

comparison to validity. If the quality of reliability is satisfied by an instrument, then while using

it we can be confident that the transient and situational factors are not interfering.

There are two aspects of reliability:

(a) The stability aspect concerned with securing consistent results with repeated

measurements of the same person and with the same instrument. We usually determine

the degree of stability by comparing the results of repeated measurements.

(b) The equivalence aspect considers how much error may get introduced by different

investigators or different samples of the items being studied. A good way to test for the

equivalence of measurements by two investigators is to compare their observations of the

same events.

Reliability can be improved in the following two ways:

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 20

Research Methodology

(i) By standardizing the conditions under which the measurement takes place i.e., we must

ensure that external sources of variation such as boredom, fatigue, etc., are minimised to

the extent possible. That will improve stability aspect.

(ii) By carefully designed directions for measurement with no variation from group to group,

by using trained and motivated persons to conduct the research and also by broadening

the sample of items used. This will improve equivalence aspect.

3. Test of Practicality

The practicality characteristic of a measuring instrument can be judged in terms of economy,

convenience and interpretability. From the operational point of view, the measuring instrument

ought to be practical i.e., it should be economical, convenient and interpretable. Economy

consideration suggests that some trade-off is needed between the ideal research project and that

which the budget can afford. The length of measuring instrument is an important area where

economic pressures are quickly felt. Although more items give greater reliability as stated

earlier, but in the interest of limiting the interview or observation time, we have to take only few

items for our study purpose. Similarly, data-collection methods to be used are also dependent at

times upon economic factors. Convenience test suggests that the measuring instrument should be

easy to administer. For this purpose one should give due attention to the proper layout of the

measuring instrument. For instance, a questionnaire, with clear instructions (illustrated by

examples), is certainly more effective and easier to complete than one which lacks these features.

Interpretability consideration is especially important when persons other than the designers of

the test are to interpret the results.

Lecture notes by Esther Njoki

Page | 21

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- CTH202 0 PDFDocumento161 pagineCTH202 0 PDFZubair AnjumNessuna valutazione finora

- Katarina Loncarevic Fem Epistemologija PDFDocumento133 pagineKatarina Loncarevic Fem Epistemologija PDFdickicaNessuna valutazione finora

- SL Literary Criticism Paper 2012Documento10 pagineSL Literary Criticism Paper 2012Dîrmină Oana DianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit-10 Feminist Approach PDFDocumento12 pagineUnit-10 Feminist Approach PDFRAJESH165561100% (1)

- Korichi Chahba AbirDocumento43 pagineKorichi Chahba AbirNitu GeorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Davide Tarizzo - The Untamed OntologyDocumento10 pagineDavide Tarizzo - The Untamed OntologyMike PugsleyNessuna valutazione finora

- A NewCriticismDocumento2 pagineA NewCriticismMeti MallikarjunNessuna valutazione finora

- Beckett Nihilism and TranscendenceDocumento30 pagineBeckett Nihilism and TranscendenceAnonymous Fwe1mgZNessuna valutazione finora

- 4) The Limits of Representation - Michel FoucaultDocumento2 pagine4) The Limits of Representation - Michel Foucaultrayrod614Nessuna valutazione finora

- 4583 PDFDocumento302 pagine4583 PDFEnrique Mauricio IslaNessuna valutazione finora

- Beckett PDFDocumento34 pagineBeckett PDFKhushnood AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Meike SchalkDocumento212 pagineMeike SchalkPetra BoulescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Course & Seminar Requirements: of 5 For Seminar Assignments Will Not Be Able To Sit The Exam!!!Documento2 pagineCourse & Seminar Requirements: of 5 For Seminar Assignments Will Not Be Able To Sit The Exam!!!Dîrmină Oana DianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fanon, Frantz - Conclusion From The Wretched of The EarthDocumento3 pagineFanon, Frantz - Conclusion From The Wretched of The EarthprimacyOf100% (1)

- Ma ThesisDocumento103 pagineMa ThesisMythBuster ÑîtïshNessuna valutazione finora

- Austin - Being Without Thought (DRAFT)Documento14 pagineAustin - Being Without Thought (DRAFT)Michael AustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Illiad Oscar Wilde's Society Comedies and Victorian Anthropology PDFDocumento17 pagineIlliad Oscar Wilde's Society Comedies and Victorian Anthropology PDFIulia100% (1)

- Brady Thomas Heiner - Foucault and The Black Panthers - City 11.3Documento45 pagineBrady Thomas Heiner - Foucault and The Black Panthers - City 11.3GrawpNessuna valutazione finora

- Earth Most Strangest Man TranscribedDocumento110 pagineEarth Most Strangest Man TranscribedGary CongoNessuna valutazione finora

- Foucault K - SCuFI - PaperDocumento90 pagineFoucault K - SCuFI - PaperKelly YoungNessuna valutazione finora

- A Foucualtian Xplination of Race Bynd FoucualtDocumento19 pagineA Foucualtian Xplination of Race Bynd FoucualtLawrence Grandpre0% (1)

- Heart of Darkness Contextual Overview AnDocumento33 pagineHeart of Darkness Contextual Overview AnAeosphorusNessuna valutazione finora

- Shakespeare's Sonnet 18Documento3 pagineShakespeare's Sonnet 18Anonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- A Christian Perspective of Love in Hemingway's A Farewell To ArmsDocumento9 pagineA Christian Perspective of Love in Hemingway's A Farewell To ArmsJimmy PautzNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Point KiplingDocumento8 paginePower Point Kiplingapi-313775083Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Farewell To Arms FinalDocumento4 pagineA Farewell To Arms Finalapi-331462681Nessuna valutazione finora

- Foucault BibliographyDocumento35 pagineFoucault Bibliographyblue_artifactNessuna valutazione finora

- Full TextDocumento281 pagineFull TextAnđela AračićNessuna valutazione finora

- Formal Literary Essay On Spinozism and ExistentialismDocumento9 pagineFormal Literary Essay On Spinozism and ExistentialismFahim Khan100% (8)

- Hyde PresentationDocumento5 pagineHyde PresentationDara Doran MillerNessuna valutazione finora

- Rhetoric Essay - Chayanika ChaudhuriDocumento9 pagineRhetoric Essay - Chayanika ChaudhurichayanikaNessuna valutazione finora

- C.p.texte AnalysisDocumento7 pagineC.p.texte AnalysisGabriela MacareiNessuna valutazione finora

- Literary Criticism - Writing ChecklistDocumento2 pagineLiterary Criticism - Writing ChecklistKel LiNessuna valutazione finora

- Literary Critical ApproachesDocumento18 pagineLiterary Critical ApproachesLloyd LagadNessuna valutazione finora

- Saposnik - DR Jekyll MR HydeDocumento18 pagineSaposnik - DR Jekyll MR HydeFrank ManleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Cache of ArabiaDocumento76 pagineCache of ArabiaMohamed EnglishNessuna valutazione finora

- Definition of HumanismDocumento9 pagineDefinition of HumanismElma OmeragicNessuna valutazione finora

- HL Essay FinalDocumento5 pagineHL Essay FinalGriffinNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison Between Old Man and The Sea and Farewell To ArmsDocumento4 pagineComparison Between Old Man and The Sea and Farewell To Armschintan16593100% (1)

- Derrida Nietzsche and The MachineDocumento4 pagineDerrida Nietzsche and The MachineAbo Borape NinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Literary CriticismDocumento6 pagineLiterary CriticismUpUl Kumarasinha0% (2)

- Essay OutlineDocumento7 pagineEssay OutlineJoseph MitchellNessuna valutazione finora

- Women For Joseph ConradDocumento87 pagineWomen For Joseph ConradjonesthebutcherNessuna valutazione finora

- The Concept of Friendship in Waiting for GodotDocumento5 pagineThe Concept of Friendship in Waiting for GodotDanilo JuliãoNessuna valutazione finora

- Edited Farewell To Arms EssayDocumento4 pagineEdited Farewell To Arms Essayapi-492391493Nessuna valutazione finora

- Buddha, and Confucius's Analects. What Virtues Characterize A Good Leader? What Actions?Documento5 pagineBuddha, and Confucius's Analects. What Virtues Characterize A Good Leader? What Actions?James Melo-Gurny Bobby100% (1)

- Angels Cosma Ioana I 200911 PHD ThesisDocumento295 pagineAngels Cosma Ioana I 200911 PHD Thesispavnav72Nessuna valutazione finora

- 20th Century Literature GuideDocumento10 pagine20th Century Literature GuideKhalil AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Olivia Gatwood's "Ode to my Bitch FaceDocumento2 pagineOlivia Gatwood's "Ode to my Bitch FaceJazzmin DulceNessuna valutazione finora

- Man as Innately Evil or GoodDocumento24 pagineMan as Innately Evil or GoodCandido MarjolienNessuna valutazione finora

- Angela Dwyer ThesisDocumento404 pagineAngela Dwyer ThesisEmma TamașNessuna valutazione finora

- Eight Months In Hell-God Helps Those Who Helps ThemselvesDa EverandEight Months In Hell-God Helps Those Who Helps ThemselvesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Foucauldian Criticism of Eliot's Tradition and The Individual TalentDocumento12 pagineFoucauldian Criticism of Eliot's Tradition and The Individual TalentMahmud ImranNessuna valutazione finora

- Derrida 4Documento210 pagineDerrida 4samankariNessuna valutazione finora

- An Answer To The Question: What Is Enlightenment?Documento5 pagineAn Answer To The Question: What Is Enlightenment?Farooq RahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Archive and The Human Sciences Notes Towards A Theory of The ArchiveDocumento17 pagineThe Archive and The Human Sciences Notes Towards A Theory of The ArchiveJosé Manuel CoronaNessuna valutazione finora

- Death in The Woods by Sherwood AndersonDocumento3 pagineDeath in The Woods by Sherwood AndersonpharezeNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methodology PDFDocumento28 pagineResearch Methodology PDFPriyanka BalapureNessuna valutazione finora

- Steps Involved in Conducting Literature ReviewDocumento8 pagineSteps Involved in Conducting Literature Reviewafdtktocw100% (1)

- Quantitative ResearchDocumento6 pagineQuantitative ResearchJan Michael R. RemoladoNessuna valutazione finora

- Stabilization of Soils With Lime and Sodium SilicateDocumento90 pagineStabilization of Soils With Lime and Sodium SilicatesamwelNessuna valutazione finora

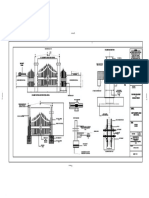

- Modern 3 Bedroom HouseplanDocumento3 pagineModern 3 Bedroom HouseplansamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Bedroom MaisonnetteDocumento1 pagina3 Bedroom MaisonnettesamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture Notes Foundation EngineeringDocumento83 pagineLecture Notes Foundation Engineeringsamwel100% (1)

- Geographic Information System and Civil EngineeringDocumento5 pagineGeographic Information System and Civil Engineeringsamwel100% (1)

- Silos Construction ReportDocumento56 pagineSilos Construction Reportsamwel79% (14)

- Prostate CancerDocumento19 pagineProstate CancersamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- GisDocumento4 pagineGissamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- School GateDocumento1 paginaSchool GatesamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- Hangin CalculationDocumento85 pagineHangin CalculationAlbert LuckyNessuna valutazione finora

- Design of 6 Storey Building in EtabsDocumento51 pagineDesign of 6 Storey Building in EtabsMisqal A Iqbal100% (2)

- Design Structural Steel Design and Construction PDFDocumento59 pagineDesign Structural Steel Design and Construction PDFdkaviti100% (2)

- Design Structural Steel Design and Construction PDFDocumento59 pagineDesign Structural Steel Design and Construction PDFdkaviti100% (2)

- Different House Sketch Plans and Pricing in KenyaDocumento5 pagineDifferent House Sketch Plans and Pricing in KenyasamwelNessuna valutazione finora

- Hangin CalculationDocumento85 pagineHangin CalculationAlbert LuckyNessuna valutazione finora

- Calculation For Short Circuit Current Calculation Using IEC / IEEE StandardDocumento11 pagineCalculation For Short Circuit Current Calculation Using IEC / IEEE StandardibmmoizNessuna valutazione finora

- LEARNING GUIDE-spreadsheet (Repaired)Documento53 pagineLEARNING GUIDE-spreadsheet (Repaired)Abel ZegeyeNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Image Processing TechniquesDocumento34 pagineDigital Image Processing Techniquesaishuvc1822Nessuna valutazione finora

- Oracle Coherence Admin GuideDocumento156 pagineOracle Coherence Admin Guidegisharoy100% (1)

- Chemical Equilibrium ExplainedDocumento42 pagineChemical Equilibrium ExplainedDedi WahyudinNessuna valutazione finora

- EWDLEWML Servo Motor DriverDocumento14 pagineEWDLEWML Servo Motor DriverWaleed LemsilkhiNessuna valutazione finora

- ALE Between Two SAP SystemsDocumento24 pagineALE Between Two SAP Systemsraghava nimmala100% (1)

- Ws2 PascalDocumento3 pagineWs2 PascalsalahadamNessuna valutazione finora

- An Intelligent Algorithm For The Protection of Smart Power SystemsDocumento8 pagineAn Intelligent Algorithm For The Protection of Smart Power SystemsAhmed WestministerNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is XRF ?: Prepared by Lusi Mustika SariDocumento34 pagineWhat Is XRF ?: Prepared by Lusi Mustika SariBayuNessuna valutazione finora

- Accelerate your career with online coursesDocumento22 pagineAccelerate your career with online coursesAYEDITAN AYOMIDENessuna valutazione finora

- Unit - L: List and Explain The Functions of Various Parts of Computer Hardware and SoftwareDocumento50 pagineUnit - L: List and Explain The Functions of Various Parts of Computer Hardware and SoftwareMallapuram Sneha RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Wound ScaleDocumento4 pagineWound ScaleHumam SyriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 8 Diagnostic Test 2022-2023Documento2 pagineGrade 8 Diagnostic Test 2022-2023JennyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rac NotesDocumento16 pagineRac NotesJohnRay LominoqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Balmer PDFDocumento3 pagineBalmer PDFVictor De Paula VilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Amber & Company: A Reliable Company of WaterproofingDocumento20 pagineAmber & Company: A Reliable Company of WaterproofingRaj PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 - Molecules and Compounds: Practice TestDocumento2 pagine3 - Molecules and Compounds: Practice Testfamily_jvcNessuna valutazione finora

- Inductive Proximity Sensors: Brett Anderson ECE 5230 Assignment #1Documento27 pagineInductive Proximity Sensors: Brett Anderson ECE 5230 Assignment #1Rodz Gier JrNessuna valutazione finora

- Maintenance Recommendations: Operation and Maintenance ManualDocumento10 pagineMaintenance Recommendations: Operation and Maintenance ManualAmy Nur SNessuna valutazione finora

- Correct AnswerDocumento120 pagineCorrect Answerdebaprasad ghosh100% (1)

- Wi Cswip 3.1 Part 13Documento7 pagineWi Cswip 3.1 Part 13Ramakrishnan AmbiSubbiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Tools - For - Problem - Solving (Appendix B), R.K. Malik's Newton Classes PDFDocumento48 pagineTools - For - Problem - Solving (Appendix B), R.K. Malik's Newton Classes PDFMoindavis DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- Acids and Bases NotesDocumento17 pagineAcids and Bases NotesNap DoNessuna valutazione finora

- AC Assingment 2Documento3 pagineAC Assingment 2Levi Deo BatuigasNessuna valutazione finora

- Math10 Week3Day4 Polynomial-EqnsDocumento44 pagineMath10 Week3Day4 Polynomial-EqnsMark Cañete PunongbayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Gas-Insulated Switchgear: Type 8DN8 Up To 170 KV, 63 Ka, 4000 ADocumento33 pagineGas-Insulated Switchgear: Type 8DN8 Up To 170 KV, 63 Ka, 4000 APélagie DAH SERETENONNessuna valutazione finora

- Connector Python En.a4Documento98 pagineConnector Python En.a4victor carreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- KujiDocumento17 pagineKujiGorumbha Dhan Nirmal Singh100% (2)

- Order Change Management (OCM)Documento19 pagineOrder Change Management (OCM)Debasish BeheraNessuna valutazione finora