Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Meranda Vs Gusweiler216 3

Caricato da

wmdtvmatt0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

583 visualizzazioni14 paginePlaintiff, Tina meranda, has filed this case against defendant, THE HONORABLE judge Scott T. Gusweiler. She alleges the judge has exhibited a pattern and practice of abusive, overbearing behavior. She says the judge has ordered a high profile Court of Appeals case out of her office.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

meranda_vs_gusweiler216_3

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoPlaintiff, Tina meranda, has filed this case against defendant, THE HONORABLE judge Scott T. Gusweiler. She alleges the judge has exhibited a pattern and practice of abusive, overbearing behavior. She says the judge has ordered a high profile Court of Appeals case out of her office.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

583 visualizzazioni14 pagineMeranda Vs Gusweiler216 3

Caricato da

wmdtvmattPlaintiff, Tina meranda, has filed this case against defendant, THE HONORABLE judge Scott T. Gusweiler. She alleges the judge has exhibited a pattern and practice of abusive, overbearing behavior. She says the judge has ordered a high profile Court of Appeals case out of her office.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 14

INTHE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS

BROWN COUNTY, OHIO

TINA MERANDA

Plaintiff,

v.

HON. SCOTT T. GUSWEILER

Defendant.

CV20100317

Judge Nurre

DEFENDANT THE HONORABLE

SCOTT T. GUSWEILER’S MOTION

TO DISMISS AND

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT

THEREOF

Comes now defendant, the Honorable Judge Scott T. Gusweiler, by and through

counsel, pursuant to Rule 12(B)(6) of the Ohio Rules of Civil Procedure, and respectfully

requests this Court dismiss plaintiff's claims against him, with prejudice. A

memorandum in support is attached.

Respectfully submitted,

Abie

GEORGE D. JON: (0027124)

LISA M. ZARING (0080659)

MONTGOMERY, RENNIE & JONSON

Coupsel for Defendant, the

Honorable Judge Scott T. Gusweiler

36 East Seventh Street, Suite 2100

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Tel: (513) 241-4722

Fax: (513) 241-8775

Izaring@mrjlaw.com

eS O

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT

E Allegations

Plaintiff, Tina Meranda, the Brown County Clerk of Court, has filed this case

against defendant, the Honorable Judge Scott T. Gusweiler of the Brown County Court

of Common Pleas, complaining that the two have had conflicts since Judge Gusweiler

took office.

In her complaint, Meranda sets out a number of occasions in which the judge has

done something she disproves of, including: instructing her staff not to accept filings

that contained the name of his predecessor (Complaint, 1 9); directing Meranda and her

staff to use the Treasurer’s mail meter, as opposed to stamps, when the clerk's mail

meter became unusable (Id. at { 10); ordering a new phone system (Id. at 11-12); and

ordering a high profile Court of Appeals case out of her office (Id. at 115.). In sum, she

alleges the judge has “exhibited a pattern and practice of abusive, overbearing, and

inappropriate behavior® * *.” Id. at 18.

Although Meranda asserts the issues between the two have been ongoing, her

current claims against Judge Gusweiler primarily stem from one incident. In February

2010, Meranda changed the locks on the clerk of court's office. Id. at 1.17. Judge

Gusweiler asked for a copy of the keys. Id. at 118. Meranda called the prosecutor, who

informed her that she should not turn over the keys without a written court order. Id. at

4118. When she and the prosecutor arrived at the courthouse, Judge Gusweiler provided

her with an order and, according to Meranda, advised her that noncompliance with the

+ In considering this Civ.R.12(B)(6) motion, this Court must accept as true all of the allegations of

the complaint. Perrysburg Twp. v. Rossford, 103 Ohio St.34 79, 2004 Ohio 4362, 15. However, even

assuming, arguendo, that all of the allegations in Meranda’s complaint are true, Meranda's claims against

Judge Gusweiler still fail to state a claim because she is absolutely immune from suit.

© ; O

order would result in a finding of contempt. Id. at $19. Meranda alleges she gave the

judge the keys out of fear of him and his demeanor. Id. at 420.

Based on their exchange, Meranda is suing Judge Gusweiler for violating Ohio's

bribery and intimidation statute, R.C. 2921.03. Id. at 1 21-23. She claims Judge

Gusweiler:

Knowingly and by force, and by unlawful threat of harm to person or

property, or by filing, recording, or otherwise using a materially false or

fraudulent writing with malicious purpose, in bad faith, or in wanton or

reckless manner, attempt{ed] to influence, intimidate, or hinder a public

servant in the discharge of the person's duty.

Id. at $22, citing R.C. 2921.03. Meranda asks this Court to hold the judge civilly liable

for violating the above statute. Id. at 123. She further seeks an order from this Court

enjoining Judge Gusweiler from exceeding his duties as a common pleas court judge and

interfering with the performance of her duties as the clerk of court. Id. at $26. And she

demands this Court issue declaratory relief stating that, outside the scope of his power

as common pleas court judge, Judge Gusweiler is not permitted to interfere with

Meranda in the performance of her duties. Id. at 131.

For the following reasons, Meranda’s claims against Judge Gusweiler fail as a

matter of law, and dismissal is appropriate.

Analysis

I, Judge Gusweiler is absolutely immune from monetary damages.

Meranda is seeking compensatory damages against Judge Gusweiler for actions

he took in his capacity as a judge. Specifically, she alleges the judge threatened her with

contempt in an effort to intimidate or hinder her in-the discharge of her duties as a

clerk. (Complaint, 22.) Such claims are barred by the doctrine of judicial immunity

and must be dismissed.

O : O

Federal law has long held that judges are immune from claims for money

damages in connection with judicial acts unless there is a clear absence of all

jurisdiction. Stump v. Sparkman (1978), 435 U.S. 349, 362, 98 S.Ct. 1099, 55 L.Ed.2d

331. Ohio courts are in accord with federal law. See Wilson v. Neu (1984), 12 Ohio St.3d

102, 103, 465 N.E.2d 854. In fact, Ohio recognizes that “[flew doctrines were more

solidly established at common law than the immunity of judges from liability for

damages for acts committed within their judicial jurisdiction***.” _Newdick v. Sharp

(2967), 13 Ohio App.2d 200, 201, 42 0.0.2 344, 235 N.E.2d 529.

Judges are absolutely immune from liability for the performance of any judicial

act unless there is an absence of jurisdiction. State ex. rel. Fischer v. Burkhardt (1993),

66 Ohio St.3d 189, 610 N.E.2d 999; Kelly v. Whiting (1985), 17 Ohio St.3d 91, 93, 477

N.E.2d 1123; Wilson, 12 Ohio St.gd at 103-04; Voll v. Steele (1943), 141 Ohio St. 293,

301, 25 Ohio Op. 424, 47 N.E.2d 991; Dalhover v. Dugan (1989), 54 Ohio App.3d 55, 56,

560 N.E.2d 824. Therefore, Judge Gusweiler’s judicial immunity can only be overcome

in two situations:

1) If he was acting in the complete absence of all jurisdiction, or

2) Ifhis challenged actions were non-judicial.

Neither of the above situations exists here.

A. As a common pleas court judge, Judge Gusweiler has

jurisdiction to order compliance with a court order or be held in

contempt.

The Ohio Supreme Court has recognized that a common pleas court has both

inherent and statutory power to punish contempts. Burt v. Dodge (1992), 65 Ohio St.

3d 34, 35, 599 N.E.2d 693 (Ohio 1992), citing Zakany v. Zakany (1984), 9 Ohio St.3d

192, 9 OBR 505, 459 N.E.2d 870, syllabus. Certain powers, including the power to

O : O

punish the disobedience of a court’s order with contempt proceedings, are necessary for

the orderly and efficient exercise of justice and are inherent in a court. Zakany, 9 Ohio

St.3d 193-194, citing State, ex rel. Dow Chemical Co., v. Court (1982), 2 Ohio St.3d 119;

Hale v. State (1896), 55 Ohio St. 210, 213; Harris v. Harris (1979), 58 Ohio St.2d 303,

307, 12 0.0.34 291; State, ex rel. Turner, v. Albin (1928), 118 Ohio St. 527.

Judge Gusweiler was acting within his inherent authority as a common pleas

court judge when he informed Meranda that noncompliance with his previous order

would result in a finding of contempt. Moreover, pursuant to R.C. 2705.01? and R.C.

2705.02(A)8, the judge was acting within his jurisdiction when he made this alleged

“threat.” In State, ex rel. Edwards v. Murray (1976), 48 Ohio St.2d 303, 358 N.E.2d

577, the Supreme Court discussed a court's power to issue ex parte administrative orders

concerning the functioning of the court and to find parties in contempt when they fail to

comply with those orders:

Zangerle v. Court of Common Pleas (1943), 141 Ohio St. 70, 46 N.E.2d

865, and the cases there cited recognize the power of the court, in matters

which concern its ability to function and to carry out its basic purposes, to

issue orders ex parte and to enforce compliance. There is nothing novel in

the procedure nor is it essentially violative of the rights of those affected,

especially where an opportunity to be heard is provided.

2 RC, 2705.01 provides: “A court, or judge at chambers, may summarily punish

person guilty of misbehavior in the presence of or so near the court or judge ai

obstruct the administration of justice.”

RC. 2705.02(A) provides, in pertinent part, “a person guilty of any of the

following acts may be punished as for a contempt: (A) Disobedience of, or resistance to,

a lawful writ, process, order, rule, judgment, or command of a court or an officer*+*”

O : O

Judge Gusweiler had jurisdiction for immunity purposes to issue the order and enforce

the order, if need be, through a contempt order. His immunity cannot be challenged on

this point.

B. Judge Gusweiler’s alleged action—threatening Meranda with

contempt—was a judicial act.

‘A judge cannot be held civilly liable for any act performed as part of his or her

judicial function. Wilson, 12 Ohio St.gd at 103 (citations omitted). When evaluating a

judicial immunity question, courts must look at a particular act’s relation to the general

function normally performed by a judge, instead of focusing on the act itself. Mireles v.

Waco (1991), 502 U.S. 9, 12-13, 112 S.Ct. 286, 116 L-Ed.2d 9, citing Stump, 435 U.S. at

536. As the Supreme Court explained in Mireles, “if only the particular act in question

‘were to be scrutinized, then any mistake of a judge in excess of his authority would

become a nonjudicial act, because an improper or erroneous act cannot be said to be

normally performed by a judge.” Id.

Here, Meranda alleges Judge Gusweiler threatened her with contempt in an

effort to intimidate or influence her in the discharge of her duties. The act in question—

threatening contempt—is directly related to the general function of a common pleas

court judge. Only a judge can hold someone in contempt; threatening to do so is, by

deduction, also a judicial act. See In re Caron (2000), Franklin C.P. Nos. 92DR-04-2101

and 99DP-04-427, 110 Ohio Misc. 2d 58, 744 N.E.2d 787, syllabus 36 (“The doctrine of

judicial immunity grants absolute immunity from civil suit to judges for their judicial

acts, including decisions regarding contempt, based upon the rationale of the overriding

public interest in judicial independence.”)

O : O

Because Judge Gusweiler was acting within his jurisdiction at the time he

allegedly threatened Meranda with contempt, and doing so is clearly a judicial act,

Meranda cannot defeat his absolute judicial immunity. Thus, Meranda’s R.C. 2921.03

claim fails, and her demand for monetary relief against Judge Gusweiler must be

denied.

I. Judge Gusweiler is qualifiedly immune from any claims relating to

the propriety of his court order.

Meranda's claims against Judge Gusweiler center on his threat of contempt, not

the issuance of the order directing her to provide him with keys to the clerk’s office.

However, even if Meranda's allegations could be construed as a challenge to Judge

Gusweiler’s order itself, her claim fails because the judge is qualifiedly immune from

suit for making a discretionary decision, in his capacity as Administrative Judge,

relating to his access to the clerk's office.

A judge performing a discretionary, administrative function is entitled to

qualified immunity from suit for civil damages unless his or her actions violate “clearly

established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have

known.” Forrester v. White, 484 U.S. 219 (1988). For Meranda to overcome Judge

Gusweiler's qualified immunity, and hold him liable for making discretionary decisions

about access to the clerk's office and the court's files, Meranda would have the burden of

establishing Judge Gusweiler deprived Meranda of a clearly defined constitutional right.

Baker v. McCollan (1979), 443 U.S. 137, 140. If the law is unclear, immunity should be

recognized. Harlow, 457 U.S. at 818. Further, Meranda would be required to prove that

a reasonably competent official would not conclude Judge Gusweiler’s conduct was

lawful. Malley v. Briggs (1986), 475 U.S. 335, 341; Cagle v. Gilley (C.A.6, 1992), 957

© : O

F.2d 1347, 1948. If officials of reasonable competence could disagree on this issue,

immunity should be recognized. 1d.

Meranda alleges Judge Gusweiler issued an order directing her to provide him

with keys to the clerk’s office. However, Meranda has failed to allege how Judge

Gusweiler’s alleged decision was improper, let alone how it violated “clearly established”

statutory or constitutional rights; therefore, Meranda fails to state a substantive claim,

and the judge is qualifiedly immune.

For a law to be clearly established, the “contours of the right must be sufficiently

clear that a reasonable official would understand that what he is doing violated that

right.” Anderson v. Creighton (1987), 483 U.S. 635, 640. The Anderson Court

emphasized that the unlawfulness must be apparent, in light of preexisting law. Id. If,

for example, other office-holders of reasonable competence (in this case, Ohio Common

Pleas Court judges) could disagree on the issue, then immunity applies. Malley, 475

U.S. at 341. Or, if the law was simply unclear, then the office holder is entitled to

qualified immunity. Harlow, 457 U.S. at 818. A right is not considered “clearly

established” unless it has been authoritatively decided by the United States Supreme

Court, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, or the highest court of the state in which the

alleged constitutional violation occurred. Robinson v. Bibb, (C.A.6, 1988) 840 F.2d 349,

351; Ohio Civil Serv. Employees Ass'n v. Seiter (C.A.6, 1988), 858 F.2d 1171, 1177

(authoritatively means the law must point unmistakably to unconstitutionality of the

conduct and be clearly foreshadowed by applicable direct authority).

Qualified immunity is unavailable only where “no reasonable official could fail to

know he or she was acting improperly.” McCloud v. Testa (C.A.6, 2000), 227 F.3d 424,

431-32 (citing Harlow, 457 U.S. at 818.). In effect, the doctrine protects “all but the

O : O

plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.” Malley, 475 U.S. at 341.

Meranda carries the burden of demonstrating no reasonable public official could

conclude Judge Gusweiler’s alleged conduct—ordering that she provide him with keys to

the clerk's office (and access to the court's files)—was lawful and that he is not,

therefore, entitled to qualified immunity. Wegener v. Covington, 933 F.2d 390, 392 (6th

Cir. 1991). She cannot meet this burden.

As the Supreme Court of Ohio has held, “[t]he duties of the clerk of court of

common pleas are ministerial and non-judicial.” State ex rel. Glass v. Chapman (1902),

67 Ohio St. 1, 65 N.E. 154, syllabus; see also State ex rel. Dawson v. Roberts (1956), 165

Ohio St. 341, 135 N.E.2d 409. Pursuant to R.C. 2303.26, the common pleas clerk of

court is required to perform her duties “* * * under the direction of the court * * *.”

Thus, Judge Gusweiler has authority to direct (via court order or rule) Meranda’s

conduct as court clerk.

This is specifically the case with regard to the court's files. The common pleas

court “has general custody of an authority over its own records and files.” Ex parte

Thayer (1926), 114 Ohio St. 194, 150 N.E. 735, syll. 11. The authority of the court over

its records and files “extends to the files of all cases which have ever been instituted

therein, whether dismissed, disposed of, or pending. The power of the court is inherent

and takes precedence even of (sic) the statutory power of a clerk over court records and

files.” Id. at 201 (citation omitted). Thus, reasonable officials would agree that Judge

Gusweiler was not acting improperly when he issued the order directing Meranda to

provide him with access to the clerk’s office and court’s files. The judge is therefore

entitled to qualified immunity for any claims relating to the court order.

O ; O

Ill. Meranda fails to state a claim against Judge Gusweiler.

Even if the above threshold defenses were not applicable to Meranda’s claims

against Judge Gusweiler, her claims still fail as a matter of law and must be dismissed.

A. Meranda fails to sufficiently state a claim under R.C. 2921.03.

Meranda brings a claim against Judge Gusweiler under Ohio's intimidation

statute, R.C. 2921.03. The statute provides, in relevant part:

(A) No person, knowingly and by force, by unlawful threat of harm to any

person or property, or by filing, recording, or otherwise using a materially

false or fraudulent writing with malicious purpose, in bad faith, or in a

wanton or reckless manner, shall attempt to influence, intimidate, or

hinder a public servant, party official, or witness in the discharge of the

person's duty.

(© A person who violates this section is liable in a civil action to any

person harmed by the violation for injury, death, or loss to person or

property incurred as a result of the commission of the offense and for

reasonable attorney's fees, court costs, and other expenses incurred as a

result of prosecuting the civil action commenced under this division. A

civil action under this division is not the exclusive remedy of a person who

incurs injury, death, or loss to person or property as a result of a violation

of this section.

Accordingly, to properly plead a claim, Meranda must allege Judge Gusweiler

threatened her, in an unlawful way or through a materially false and fraudulent filing, in

an attempt to influence her duties as clerk of court. Further, she must demonstrate she

was injured as a result of the commission of the offense.

Meranda’s claim fails for a number of reasons: First, as explained above, Judge

Gusweiler’s threat of contempt was not unlawful. As a common pleas court judge, Judge

Gusweiler is legally permitted to hold someone in contempt for violating a court order.

See Section I.A.; see also R.C. 2705.01 and R.C. 2705.02(A). Threatening to enforce his

contempt power was not improper or illegal. Further, to the extent Meranda is alleging

10

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento4 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Motion To Vacate Void JudgmentDocumento14 pagineMotion To Vacate Void Judgmenttra98ki96% (52)

- Perez v. Ledesma, 401 U.S. 82 (1971)Documento41 paginePerez v. Ledesma, 401 U.S. 82 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Edna Goldstein v. Robert E. Kelleher, United States of America, Intervenor, 728 F.2d 32, 1st Cir. (1984)Documento10 pagineEdna Goldstein v. Robert E. Kelleher, United States of America, Intervenor, 728 F.2d 32, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 08.31.21 51H.2P Re Add'n Criminal Contempts by Edgardo RamosDocumento28 pagine08.31.21 51H.2P Re Add'n Criminal Contempts by Edgardo RamosThomas WareNessuna valutazione finora

- Hugh EvansDocumento6 pagineHugh Evanssaf4130Nessuna valutazione finora

- James Douris v. Upper Makefield TWP, 3rd Cir. (2012)Documento8 pagineJames Douris v. Upper Makefield TWP, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Leroy Edward Green v. Camilla Maraio and Angelo J. Ingrassia, 722 F.2d 1013, 2d Cir. (1983)Documento9 pagineLeroy Edward Green v. Camilla Maraio and Angelo J. Ingrassia, 722 F.2d 1013, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocumento6 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanley R. Guffey v. Eldridge Wyatt, Officer, 18 F.3d 869, 10th Cir. (1994)Documento7 pagineStanley R. Guffey v. Eldridge Wyatt, Officer, 18 F.3d 869, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Riddle v. Dyche, 262 U.S. 333 (1923)Documento3 pagineRiddle v. Dyche, 262 U.S. 333 (1923)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruel Hux, Jr. v. A.I. Murphy, Warden and The State of Oklahoma, 733 F.2d 737, 10th Cir. (1984)Documento5 pagineRuel Hux, Jr. v. A.I. Murphy, Warden and The State of Oklahoma, 733 F.2d 737, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Gales v. Gatterman, 10th Cir. (2007)Documento5 pagineGales v. Gatterman, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Muniz v. Suthers, 10th Cir. (2006)Documento5 pagineMuniz v. Suthers, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tony Glen Mark v. Edward L. Evans Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 129 F.3d 130, 10th Cir. (1997)Documento5 pagineTony Glen Mark v. Edward L. Evans Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 129 F.3d 130, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- JurisdictionDocumento6 pagineJurisdictionbsperlazzo100% (2)

- Petition For Review - Third Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals Judicial MisconductDocumento31 paginePetition For Review - Third Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals Judicial MisconductEl Aemer100% (1)

- 08.29.21 51H Re Application For Leave To File Emergency Rule 42 (B) Criminal Contempt Motion To Enforce Gov.-1and Brady OrdersDocumento102 pagine08.29.21 51H Re Application For Leave To File Emergency Rule 42 (B) Criminal Contempt Motion To Enforce Gov.-1and Brady OrdersThomas WareNessuna valutazione finora

- Greschner v. Cooksey, 10th Cir. (2006)Documento6 pagineGreschner v. Cooksey, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 809, 13 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 11,556 Stanley Williams v. Wallace Silversmiths, Inc., A Division of HMW Industries, Inc., Defendant, 566 F.2d 364, 2d Cir. (1977)Documento7 pagine14 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 809, 13 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 11,556 Stanley Williams v. Wallace Silversmiths, Inc., A Division of HMW Industries, Inc., Defendant, 566 F.2d 364, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Trujillo v. Hartley, 10th Cir. (2010)Documento14 pagineTrujillo v. Hartley, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Shumway, 10th Cir. (2013)Documento8 pagineUnited States v. Shumway, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento5 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Not PrecedentialDocumento7 pagineNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Stephen Jay Songer, 842 F.2d 240, 10th Cir. (1988)Documento6 pagineUnited States v. Stephen Jay Songer, 842 F.2d 240, 10th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Walters v. Beck, 10th Cir. (2005)Documento6 pagineWalters v. Beck, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Harold Neely v. State of Pennsylvania, 411 U.S. 954 (1973)Documento5 pagineHarold Neely v. State of Pennsylvania, 411 U.S. 954 (1973)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Beauclair v. Dowd, 10th Cir. (2014)Documento4 pagineBeauclair v. Dowd, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashby v. McKenna, 331 F.3d 1148, 10th Cir. (2003)Documento10 pagineAshby v. McKenna, 331 F.3d 1148, 10th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vargas v. Everett, 10th Cir. (2003)Documento6 pagineVargas v. Everett, 10th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Clyde C. Dean v. Vernon Shirer and John Dukes Wactor, 547 F.2d 227, 4th Cir. (1976)Documento6 pagineClyde C. Dean v. Vernon Shirer and John Dukes Wactor, 547 F.2d 227, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento4 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento21 pagineFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Cooley v. Laramie County Judge, 10th Cir. (2002)Documento2 pagineCooley v. Laramie County Judge, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento5 paginePledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Janie McGhee v. Daniel D. Draper, Superintendent Daniel D. Draper Floyd E. Mott Montie Jones Jerry Stafford Don Larmon and Quentin Riley, 639 F.2d 639, 10th Cir. (1981)Documento10 pagineJanie McGhee v. Daniel D. Draper, Superintendent Daniel D. Draper Floyd E. Mott Montie Jones Jerry Stafford Don Larmon and Quentin Riley, 639 F.2d 639, 10th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Adams, 10th Cir. (2007)Documento11 pagineUnited States v. Adams, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re George SASSOWERDocumento4 pagineIn Re George SASSOWERScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ayala v. Holmes, 10th Cir. (2002)Documento6 pagineAyala v. Holmes, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Reginald Jells v. Ohio, 498 U.S. 1111 (1991)Documento6 pagineReginald Jells v. Ohio, 498 U.S. 1111 (1991)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Not PrecedentialDocumento8 pagineNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Wheeldin v. Wheeler, 373 U.S. 647 (1963)Documento15 pagineWheeldin v. Wheeler, 373 U.S. 647 (1963)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion 11112007 Commission On RetirementDocumento7 pagineDiscussion 11112007 Commission On RetirementbblurkinNessuna valutazione finora

- Dennis v. Sparks, 449 U.S. 24 (1980)Documento7 pagineDennis v. Sparks, 449 U.S. 24 (1980)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento4 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Sue A JudgeDocumento37 pagineHow To Sue A Judgelegalremedyllc100% (11)

- In Re Lonzy Oliver. Appeal of Lonzy Oliver, 682 F.2d 443, 3rd Cir. (1982)Documento5 pagineIn Re Lonzy Oliver. Appeal of Lonzy Oliver, 682 F.2d 443, 3rd Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Taurus v. U.S. Department, 10th Cir. (2012)Documento3 pagineTaurus v. U.S. Department, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ferguson Grand Juror Doe Opposition To DismissDocumento21 pagineFerguson Grand Juror Doe Opposition To DismissJason Sickles, Yahoo News0% (1)

- United States v. Juliet Maragh, 189 F.3d 1315, 11th Cir. (1999)Documento5 pagineUnited States v. Juliet Maragh, 189 F.3d 1315, 11th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- When is a Judge Entitled to Absolute ImmunityDocumento12 pagineWhen is a Judge Entitled to Absolute ImmunityTheOdysseyNessuna valutazione finora

- Alan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Documento6 pagineAlan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Wilbert Brown, JR., 744 F.2d 905, 2d Cir. (1984)Documento9 pagineUnited States v. Wilbert Brown, JR., 744 F.2d 905, 2d Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutun v. United States, 270 U.S. 568 (1926)Documento6 pagineTutun v. United States, 270 U.S. 568 (1926)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Will v. United States, 389 U.S. 90 (1967)Documento15 pagineWill v. United States, 389 U.S. 90 (1967)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mordecai Agur v. The Honorable Malcolm Wilson (As Successor in Office To The Honorable Nelsona. Rockefeller), Governor of The State of New York, 498 F.2d 961, 2d Cir. (1974)Documento10 pagineMordecai Agur v. The Honorable Malcolm Wilson (As Successor in Office To The Honorable Nelsona. Rockefeller), Governor of The State of New York, 498 F.2d 961, 2d Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Jean Coulter v. Thomas Doerr, 3rd Cir. (2012)Documento5 pagineJean Coulter v. Thomas Doerr, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Ahmed, 10th Cir. (2000)Documento7 pagineUnited States v. Ahmed, 10th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeDa EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- An Introduction To Ineffective Assistance of CounselDa EverandAn Introduction To Ineffective Assistance of CounselNessuna valutazione finora

- Congressional Redistricting Regional Hearing ScheduleDocumento1 paginaCongressional Redistricting Regional Hearing ScheduleohiohousegopNessuna valutazione finora

- National DebtDocumento1 paginaNational DebtwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Bird Special Press ReleaseDocumento1 paginaEarly Bird Special Press ReleasewmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Mary Swain Flyer IIDocumento2 pagineMary Swain Flyer IIwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Committee AssignmentsDocumento4 pagineCommittee AssignmentswmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- SubSB5 Comparative SynopsisDocumento9 pagineSubSB5 Comparative SynopsiswmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- As Introduced 129th General Assembly Regular Session H. B. No. 3 2011-2012Documento7 pagineAs Introduced 129th General Assembly Regular Session H. B. No. 3 2011-2012wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Wilson Reading Veteran ReadDocumento2 pagineWilson Reading Veteran ReadwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Carter FundraiserDocumento1 paginaCarter FundraiserwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- VFW-PAC Endorses BoehnerDocumento1 paginaVFW-PAC Endorses BoehnerwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Pix in ParksDocumento3 paginePix in ParkswmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Letter To DSShawneevalleyDocumento8 pagineSecond Letter To DSShawneevalleywmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- A Pledge To AmericaDocumento48 pagineA Pledge To AmericawmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Press Release VOA Traffic Pattern 9.28.10Documento1 paginaPress Release VOA Traffic Pattern 9.28.10wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

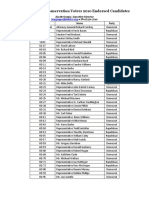

- 2010 Endorsed Candidates Press Release List 97-2003Documento1 pagina2010 Endorsed Candidates Press Release List 97-2003wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Ohio House GOP Government Reform PackageDocumento1 paginaOhio House GOP Government Reform PackageohiohousegopNessuna valutazione finora

- Cite As State Ex Rel. Varnau v. Wenninger, 2010-Ohio-3813.Documento5 pagineCite As State Ex Rel. Varnau v. Wenninger, 2010-Ohio-3813.wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- OEC Complaint CombsDocumento3 pagineOEC Complaint CombswmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- De Wine LetterDocumento2 pagineDe Wine LetterwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Future of Ohio JobsDocumento1 paginaFuture of Ohio JobsJimmy SheppardNessuna valutazione finora

- Economist StatementDocumento9 pagineEconomist StatementwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Retherford Campaign Brochure 2Documento1 paginaRetherford Campaign Brochure 2wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Ohio Where Are The JobsDocumento18 pagineOhio Where Are The JobswmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- DisapprovalDocumento2 pagineDisapprovalwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Chris Vs Jenny DismissalDocumento3 pagineChris Vs Jenny DismissalwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- Ohio Sup CT Race Concerns 3-5Documento2 pagineOhio Sup CT Race Concerns 3-5wmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- 02.03.10 - Government Reform PackageDocumento1 pagina02.03.10 - Government Reform PackagewmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- OH-18 NW21 Permit ReleaseDocumento1 paginaOH-18 NW21 Permit ReleasewmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora

- BrokerCheck ReportDocumento19 pagineBrokerCheck ReportwmdtvmattNessuna valutazione finora