Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Finalpaper6590 Southcombecombined

Caricato da

api-312293668Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Finalpaper6590 Southcombecombined

Caricato da

api-312293668Copyright:

Formati disponibili

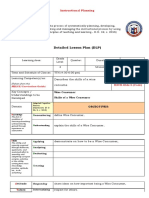

Running head: BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Using Blended Learning with At-Risk Students in Outreach Schools.

Jennifer Southcombe

Memorial University of Newfoundland

Author Note

Correspondence can be addressed to 4336 148 Street, Edmonton, AB, T6H 5V5. Contact:

jasouthcombe@gmail.com

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Abstract

Outreach schools are alternative programs that provide personalized education to students

choosing not to attend or unable to attend traditional schools. The majority of Outreach

students are considered at-risk and Outreach teachers are always looking for new ways to

improve at-risk student success - be it graduation rates or achievement. A variety of blended

learning models are analyzed for potential use in an Outreach school setting. The Flex Model,

the Enriched Virtual model and variations on these were found to be the most suitable for the

Outreach school setting. Blended learning is found to improve student success more than

traditional face-to-face or online learning alone. Initial blended learning research involving

at-risk students suggests similar results. However, due to the limited nature of this research

on K-12 at-risk students specifically in blended learning environments, more empirical

studies must be performed before robust conclusions can be formed.

Table of Contents

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Abstract

Table of Contents

Introduction

Definition of Blended Learning

Outreach Schools

Blended Learning

Models

8

8

Rotation Model

Flex Model

11

A-La-Carte Model

13

Enriched Virtual Model

13

Variations on the Models

14

Blended Learning Outcomes

16

At-Risk Students

18

Conclusion

22

References

25

Using Blended Learning with At-Risk Students in Outreach Schools.

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

There is much hype, conversation and controversy around blended learning in

Canada and across the United States. Horn and Evans (2013) argue that blended learning will

be the disruptive innovation that transforms the education system from the current one-sizefits-all transmissive model to a student-centric system customized for each students distinct

learning needs and [will] bolster each student's achievement (p. 26). The 2015 K-12

Horizon Report identifies the increased use of blended learning as an important trend that will

drive educational technology adoption over the next 1-2 years (Johnson, Adams Becker,

Estrada & Freeman, 2015). Teachers are always looking for ways to mitigate some of the

disadvantages of the learning environment in which they teach; According to Akkoyunlu and

Soylu (2008), these disadvantages have teachers searching for ways to combine the

advantages of e-learning and traditional learning environments resulting in a new learning

environment known as blended learning. Barbour and LaBonte (2014) explain that blended

learning use in Canada has been increasing and cite the astonishing statistic that from 2011

to 2014 the Ontario Ministry of Education coordinated an initiative to roll out access to

blended learning for all K-12 students, which resulted in almost 240,000 blended learning

enrollments in the provincial learning management system during the 2013-14 school year

(p. 1).

Some school leaders are recognizing the potential for online and blended learning to

provide access to advanced courses, low-incidence courses, courses for credit recovery, and

courses designed for students with special circumstances (Raymond, Smith, Johnson and

Glick, 2015, p.71). Teachers working with diverse student groups, such as in an Outreach

school, could capitalize the on these potential opportunities. As blended learning becomes

more main-stream there is value in understanding whether the blended learning approach

would help improve the instruction at Outreach schools. Moving to blended learning would

entail large investments in computer software and teacher course development time, but has

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

the potential to dramatically improve these student supports. Before large investments are

made by individual Outreach teachers the following research question needs to be answered:

How would a blended learning approach influence at-risk student success in an Outreach

school environment?

Definition of Blended Learning

The definition of blended learning can be quite broad as it contains many models and

variations on the models. According to Graham (2006), blended learning combines face-toface learning with distributed learning systems that rely heavily on technology. Horn and

Evans (2013) describe blended learning as learning that combines online learning with

elements of a brick-and-mortar experience (p. 22). Staker and Horn (2012) extend this

definition by adding that there must be some element of student control over time, place,

path and/or pace (p. 3). Watson (2008) views blended learning as a pedagogical approach

that combines the effectiveness and socialization opportunities of the classroom with the

technologically enhanced active learning possibilities of the online environment, rather than a

ratio of delivery modalities (p.4). Others have also extended the blended learning definition

into the pedagogical realm rather than focussing on the modality; Patrick, Kennedy and

Powell (2013) explain that blended learning involves an explicit shift of the classroom-level

instructional design to optimize student learning and personalize learning and should

provide greater student control and flexibility in pathways for how a student learns, where

and when a student learns and how they demonstrate mastery (p14).

McRae (2015) has voiced valid concerns that the ambiguity of some of these

definitions will allow private companies to come in and define the space in order to sell their

particular product ranging from full suite of eLearning courses to specific educational

courseware. These issues are creating questions about the future role of the teacher and the

appropriate use of technology in education. McRae (2015) believes that technologies should

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

be employed to help students become empowered citizens rather than passive consumers

and encourages teachers to claim the blended learning space (p.26). However, to claim this

space (and the term) from for-profit companies, teachers must understand blended learning.

Blended learning is a trend in education showing up around the world. In Singapore

all teachers are prepared to teach online and in blended learning environments. This training

is emphasised during the one week a year when the school buildings close and all school is

taught online (Dichev, Dicheva, Agre & Angelova, 2013). A handful of US states have even

passed laws that require every K-12 student, before graduation, to experience at least one

online learning course (Kennedy and Archambault, 2015). These directions are beginning to

force a model of blended learning on a large number of students and teachers making an

examination of blended learning research timely.

Outreach Schools

Outreach schools are a current system of alternative education put into place to

prevent [students] leaving before graduation or to facilitate their return if they do leave

prematurely (Housego, 1999, p.85). Typically, Outreach schools are brick-and-mortar

schools that individualize student instruction through the use of print-based distance

education materials and individual student program plans that allow for personalized course

sequencing and pacing, credit recovery options, non-attendance options and face-to-face

tutorial supports. Outreach staff recognize that each student is unique and attempt to give

students what they themselves feel they need instead of focusing on what others decide they

need (Housego, 1999). Students progress at their own rate and the choice to attend is

typically as they wish, with some choosing to attend daily, weekly or only show up to submit

and pick-up new materials. This attempt to meet the needs of a very diverse student body has

led to the educational innovation of the Outreach school (Housego, 1999).

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Even with all this innovation in education, technology and online learning options

have been slow to make their way to most of these alternative schools. Outreach teachers are

still finding what studies by Longhurst and OHara (2003) and Sellen (1997) found, that large

numbers of learners still prefer reading from paper prints. However, this preference for print

has noticeably been changing as of late. Inequitable access to technology by students from

lower socioeconomic backgrounds has also been claimed as a reason to not promote online

courses or online course content in the Outreach school settings (Brown, 2000). However,

every year mobile technologies are becoming more and more available and according to the

Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association, in 2013, ownership of at least one cell

phone was reported by 84.9% of households (CWTA, 2013). Other reasons courses may

remain in print format include teacher technology comfort levels and abilities and the time

factor associated with creating online course materials; a typical Outreach may involve one

teacher who is responsible for teaching all the high school social studies courses or even all

of the humanities courses.

Students from a wide variety of educational backgrounds choose to attend Outreach

schools; most are considered at-risk students, meaning they are at risk of not graduating or of

leaving school without an acceptable level of basic skills (Brown, 2000). There are a wide

variety of reasons that students may be at risk, including mental health or behavioral issues,

substance abuse, homelessness, full-time employment, or adolescent pregnancy (LaganaRiordan et al., 2011). Outreach students are a diverse group that have typically experienced

minimal success and many see themselves as misunderstood and unfairly treated (Housego,

1999, p.85). Some students may be attempting to complete high school while working parttime or full-time, or want to work at their own pace while other students prefer to avoid

traditional schools for social reasons (Housego, 1999, p.85). A large percentage of at-risk

students have either a learning or behavioural disability and Lange (1998) suggests that

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

looking for more innovative ways to teach will help address individual student learning

needs. When looking at the variety of circumstances and situations students are coming from,

the measuring of student success in an Outreach school will vary on a student by student case

but could include measurements of course completions, academic achievements, attendance,

engagement and graduation rates. The studies referred to in this paper most commonly use

academic achievement and graduation rates as the measures of student success.

Ferdigs (2010) summary of research on dropout prevention lists individualized

instruction as a promising practice because it provides students with just-in-time support

preventing students from getting lost and giving up (p. 10). Just-in-time support is exactly

what Outreach teachers strive for but tend to rely on the face-to-face environment or the

scaffolding embedded in the print materials for these supports.

To answer the research question, this paper will examine a variety of case studies of

blended learning models for their potential application within the confines of an Outreach

school setting. Then a thorough investigation and analysis of the empirical research on

blended learning and its effect on student success is provided. Lastly, the investigation of the

research will focus in on research that includes at-risk students in blended learning situations.

Blended Learning

Models

There are many different ideas and models of what blended learning looks like. Horn

and Staker (2015) identify and describe four main models while others use a definition of

blended learning to describe whether or not a situation falls within the realm of this type of

learning. These four models of blended learning are Rotation, Flex, A La Carte, and Enriched

Virtual (Horn & Staker, 2015). It is important to note that many variations and combinations

of these models also exist and continue to develop as teacher and school experimentation

with blended learning continues. As the models and case studies are examined, the following

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

questions will be answered: What models or examples of blended learning are being used

with at-risk students? Are any of these successful models applicable to an Outreach school

setting?

Rotation Model. Taking a look through the models, the Rotation Model is the model

that most brick and mortar classroom teachers gravitate towards as it is doable within the

confines of the classroom and the attendance requirements of the education system. The

model includes variations like station rotation, lab rotation, flipped classroom and individual

rotation as sub-types (Horn & Staker, 2015). Typically in the Rotation Model, students rotate

among learning modalities either as directed by a teacher or through the use of personal

algorithms (Horn & Staker, 2015). These stations could include online learning, small-group

instruction, whole-group instruction and pencil-and-paper assignments at student desks, in

labs or other classrooms. Monitors rather than teachers may staff computer labs freeing up

teachers to focus on concept extension and critical thinking skills (Horn & Staker, 2015 p.

41). Studies with low-income students using this model showed success in that a notable

step toward closing the achievement gap in math was made while saving large amounts of

money (Horn & Staker, 2015, p.41). While many variations on this rotation model are

proving successful, the daily attendance requirement and the expectation that facilities can

hold all the students each day, is way above what most Outreach schools can currently offer.

There is no doubt that lessons can be learned from these blended approaches but it is

important to understand the limitations of adopting these models fully in an Outreach school

setting.

The following example is a case study of two schools using the rotation model with

at-risk students. The New Orleans Public School Board has a public charter alternative high

school called the ReNew Accelerated High School that is geared toward at-risk students,

specifically those who are too old for traditional high schools and still need a number of

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

credits to graduate. Each student has a computer and the students attend school alternating

between the online learning and face-to-face learning with a traditional teacher in 4 hour

shifts. What is interesting to note is that the school switched from using online courses from

their initial provider Plato to Compass Learning Odyssey courses because the courses werent

engaging enough and quizzing was too easy. One adult student described an online creditrecovery course in world history requir[ing] next-to-no critical thinking and was allowed to

take the tests as many times as she liked to earn a passing grade (Carr, 2014, p.35). The newer

online course material has tougher quizzing, more engaging content and teachers can make

changes to the material (Carr, 2014). Teachers are also providing face-to-face mini-lessons

on difficult concepts before students begin the online lesson in an attempt to improve

understanding. The incentives and punitive measures in the United States surrounding

graduation rates, credit recovery and academic achievement is beyond the scope of this paper

but point to the value in looking deeper into each model to see if more than the modality

changes but if any pedagogical change has occurred.

The same New Orleans school district next opened the public charter Arthur Ashe

Academy as a blended learning school. The decision to be blended was due to the school

having the highest percentage of special education students of any school in New Orleans

(26%) and they felt that special education students would experience the biggest benefit

from blended learning because of its inherent personalized instruction capabilities (Watson

et. al, 2014, p. 49). During their eight-hour school day, students rotate between small groups,

whole class instruction and the computer lab with adaptive digital content. In 201213, Ashe

saw a 17% growth in math on state assessments over the previous year (Watson et. al, 2014,

p. 49).

It is interesting to note that both the blended learning models described above have a

regularly scheduled attendance requirement. The attendance requirement could potentially

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

reduce the current flexibility observed in Outreach schools but on the other hand, could be

linked to the students success. Specific research on attendance versus nonattendance policies

may be something to consider in the future. This study provides an example of a blended

learning model that improved student achievement. Unfortunately the study does not

specifically look at the at-risk student population separately from the larger student group so

the specific effect on the at-risk student population remains unknown.

Flex Model. The next model, the Flex Model of blended learning, has been used in

alternative education centers in the United States for at-risk students, credit recovery and

summer programming (Horn & Staker, 2015, p.41). In this model, content and instruction are

delivered mainly online with a teacher on-site providing supports on an as-needed basis

through activities such as small-group instruction, group projects, and individual tutoring

(Watson et. al., 2014, p.12). These programs tend to have less rigid attendance requirements

than the Rotation Model, allowing students to show up any time throughout the day to learn

via an individually customized fluid schedule among learning modalities (Horn & Staker,

2015, p.47). Wichita Public School Learning Centers are an example of the Flex Model

directed at at-risk youth and adult students - those that have dropped out or failed courses - in

response to the district's low graduation rate (Mackey, 2010). Their Learning Centers utilise

computer-based instruction under the direction of certified teachers, meaning students may

come and go any time the school is open. Mackey (2010) describes the online content as

advantageous for the following reasons:

Permits students to enroll or finish the program at any time during the year

and not follow a traditional school calendar;

Offers students a wide range of courses and course levels without requiring

a dedicated teacher for each level and subject;

Allows students to learn at their own pace and preferred time;

Enables the use of a mastery-based curriculum that ensures students are

learning as they progress through a course;

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Provides rapid, unbiased feedback that allows teachers to intervene as soon

as students begin struggling with a concept. (p. ii)

According to Mackey (2010) the districts graduation rate has risen eight percentage

points since the program first began in 1999 (p.ii). This is an example of a Flex Model that

most resembles the flexible setting of current Outreach schools.

The use of storefront locations and open-space learning centers where students come

and go according to no set schedule is the typical setting for Outreach schools. The main

differing feature between the Flex Model example above and current Outreach school model

is that the backbone of the Flex Model uses computer-based instruction or online learning

modality to deliver the majority of the course material. Many of the advantages attributed to

the online course material listed above can also be described as attributes of print course

materials except for the last point. Print course materials do not allow for rapid feedback as

the teacher interventions may be delayed days or weeks depending on when the teacher

marks the materials or the student requests help in person. As mentioned in the introduction,

Outreach teachers should strive for the ability to provide rapid feedback and the just in time

supports that can be offered through online course-wares in the hope they prevent students

from struggling and dropping out. Therefore, elements of the Flex Model have the potential

to improve conditions at an Outreach school.

A La Carte Model. The A La Carte Model is where high school students take an

online course while also attending a traditional brick-and-mortar school (Horn & Staker,

2015). This is the most common type of blended learning at the high-school level and

typically results from courses not being offered in a home school or from timetable conflicts.

This model applies mostly to the traditional school setting and may not greatly affect the

Outreach school setting.

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Enriched Virtual Model. Enriched Virtual is the fourth blended learning model and

originated from online schools wanting to enhance their online courses with required face-toface interactions (Horn & Staker, 2015). These online schools created physical learning

spaces for students to come together. Students may be required to meet once a week or daily

on a rotation schedule. Students can work on their courses and have contact with their teacher

onsite or online from home. Barbour and LaBontes (2014) findings point out that in Canada,

many traditional distance programs have modified instructional practices to include

more synchronous, live events and meetings and as part of this approach we are now

seeing many programs shift from being exclusively any time, any place, any pace to

a structured cohort intake enrollment model coupled with required live events and

group work (p.7).

Two Canadian examples that would be considered Enriched Virtual Models of

blended learning are the Argyll Centre Bridges to Achievement program and British

Columbias Navigate Program. Both of these schools originated as distance education

schools delivering online courses and have both moved to develop more blended programs in

recent years. In Edmonton, the Argyll Centre Bridges to Achievement program uses

individualized learning programs to help at-risk students requiring additional supports. The

program is a mixture of onsite weekly sessions, online virtual classroom sessions and homebased instruction (Bridges, n.d.). British Columbias Navigate Program in the

Courtenay/Comox school district also offers many diverse and innovative programs (About,

2016). One such program is the eCademy of New Technology, Engineering and Robotics or

ENTER program. This blended project-based program uses science and technology to deliver

the BC curriculum through three days a week of face-to-face learning and two days a week of

online learning. This is one of the blended programs that lead to Navigate receiving

iNACOLs 2014 Innovative Blended and Online Learning Practice Award of the year

(Barbour & LaBonte, 2014). Unfortunately most available research on these programs does

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

not extend past a description of the programs or general course completion rates for the entire

school district.

The Flex Model and the Enriched Virtual Model can begin to resemble one another as

they evolve. eLearning is the backbone of both models and large investments in online

courseware would be required if either model was to be employed by Outreach schools. Both

models but would suit the Outreach setting and flexible attendance requirements.

Variations on the models. As discussed, the definitions for blended learning can vary

greatly and so to can the various blended learning models; Watson et. al. (2014) describe

blended learning implementations as having infinite permutations, making it extremely

difficult to identify and study (p.4). Horn and Staker (2015) admit that after amending the

descriptions of the blended-learning models many times, there are blended learning programs

that mix and match the models resulting in a combination approach (p.52).

One of these mix and match or combination approaches could explain the New

Albany-Plain Schools (NAPLS) in Ohio which completely redesigned the instructional model

to offer 17 blended courses (Horn & Staker, 2015). These blended courses reduce the

traditional whole class instruction time to 1-2 days per week while providing the coursework

online during the remaining days. These courses are taught through a flexible mixture of the

physical classroom and the digital learning space. Students may complete the online work at

home instead of during the scheduled time. The teachers design their own online content and

determine the face-to-face and online components. These blended courses have shown:

statistically similar outcomes in course grades

80% of students like their blended courses

86% of these same students reported that they had the ability to work at their own pace in

their blended courses

88% of the spring 2014 students report that their blended courses were well organized in the

LMS and this made learning easier (Watson et. al., 2014, p. 47).

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

The NAPLS model above does not necessarily focus on at-risk students but does

reveal that the combination of face-to-face and online components provides students with the

opportunity to work at their own pace even within a synchronous course setting. However,

the idea of flexible pace may vary dramatically between different at-risk students - where one

student may take weeks to complete a course and another may take months - this amount of

flexibility would be difficult to achieve in a synchronous course setting. There are many other

variations on the models that could work or evolve to work in an Outreach setting. Mixing

and matching the best pieces of each of the models would allow Outreach teachers to develop

flexible blended learning situations to meet their students needs.

While not all of the examples of blended learning models discussed have been

examined through empirical research, there is still value in evaluating the various models and

combinations of models that have evolved to support and improve student success. In the

above section, an attempt was made to provide examples of models used with at-risk students

or in environments similar to the current Outreach school setting. As indicated, some of these

models are neither logistically appropriate for an Outreach setting nor appropriate for

Outreach students requiring flexible schedules.

Blended Learning Outcomes

With so many examples and vignettes offered about the different blended learning

models and variations being used it is interesting to find, as Repetto and Spitler s (2014)

review confirms, there is a lack of peer-reviewed, research-based articles on blended learning

within the Canadian context. As Barbour and LaBonte point out in the 2014 State of the

Nation, beyond a small number of descriptive, overview pieces, the British Columbia

Teachers Federation (BCTF) and Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN) have

conducted most of the existing research (p.7). However, much of this research has focussed

on online learning rather than blended learning or to understand what K-12 blended learning

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

means to the role of the teacher. With this apparent shortage of studies within the K-12

Canadian blended learning context, both international and Canadian studies will be examined

in this section. This section will focus on the quantitative research involving experimental

studies looking at student success as opposed to the research presented in the last sections

which focussed mostly on the descriptions and analysis of the various blended learning

models.

Flipped classrooms, a type of blended learning, have become very popular with high

school teachers. An experimental study of Grade 12 biology students, who had studied in a

flipped classroom style of learning -were academically more successful than the students who

studied in the traditional face-to-face learning environment (Kazu & Demirkol, 2014). Kazu

and Demirkol (2014) suggest the results are due to the fact that the students can get access to

information in any place without being limited by boundaries or spaces with blended learning

environment[s] (p. 86). In a different study of flipped learning, Mattis (2015) wanted to

compare flipped classroom instruction versus a traditional classroom and chose to

specifically look at the use of instructional videos versus the traditional textbook instruction.

The study results show that the experimental group receiving flipped instruction

demonstrated higher accuracy on the post-test than the traditional instruction setting,

specifically on items of moderate complexity (Mattis, 2015, p.244). The study also looks at

cognitive load and finds accuracy increased and mental effort decreased with flipped

instruction (Mattis, 2015, p. 231). Results such as these may be used to inform blended

learning instructional design best practices and encourage the use of instructional videos as

online course materials students can access any time.

In Najafi, Evans and Redericos (2014) study of two groups of high school students,

one group, the MOOC (massive online open course) had no face-to-face teacher support and

the second group, the blended-mode, had weekly face-to-face tutorials - found that the

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

blended students stayed more on track and were more persistent in retaking quizzes. These

findings are consistent with the literature findings summarized by Akkoyunlu and Soylu

(2008) that human support is very important for learners and it introduces a personal touch

to help with problems, sustain interest or motivate learners (p. 190).

All of the above 2014 studies corroborate the findings of an earlier important 2013

meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of both purely online and blended versions of

online learning as compared with traditional face-to-face learning. Based on the 45 studies

included in the analysis it finds that purely online learning is equivalent to face-to-face

instruction in effectiveness and that blended learning approaches are more effective than

either instruction offered entirely in face-to-face mode or purely online (Means, Toyama,

Murphy & Baki, 2013). It is also important to note that the study describes the way blended

learning situations provide for additional learning time, instructional resources, and course

elements that encourage interactions among learners (Means et. al., 2013, p.1). These

factors, shaped through the use of blended learning approaches, appear to be key elements in

instruction effectiveness and warrant further exploration in future research.

Not all studies have found blended learning to improve student achievement. One

study looking at grade 11 electrical engineering students in a vocational school found no

significant achievement differences between students learning in the traditional method

versus a blended learning method over a 5 week period. However, they did find significant

differences in the self-assessments scores in that the blended learning experimental group had

higher self-assessment scores than the control group. Chang, Shu, Liang, Tseng, and Hsu

(2014) explain that the blended learning experimental group had more positive perceptions

of cognition and skill because the blended e-learning provides both a traditional learning

and an e-learning environment at the same time, which enables students to review the

material repeatedly and discuss with peers online (p. 225).

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

The blended learning approach, whether flipping a classroom through the use of video

instruction or adding face-to-face elements to purely online MOOCS, improves student

success. Will this student success observed above also be observed in at-risk student

populations? The next section will focus specifically on the research looking at at-risk student

success in blended learning environments.

At-Risk Students

While the above studies do not specifically look at at-risk student achievement in

blended learning environments there is value in exploring the elements of blended learning

that have produced successful results in the general student population. Finding empirical

studies of blended learning within the K-12 context was challenging enough but to find

research that extended to at-risk students proved an even greater challenge. Many researchers

have commented that at-risk students have become a significant percentage of the K-12

online and blended learning student population but there is a great lack of empirical research

in support of this shift (Barbour, 2009; Repetto & Spitler, 2014). It is important to note that

"students identified as at-risk often include students with disabilities" (Repetto & Spitler,

2014, p. 112). Therefore it is relevant to look at research that includes blended learning and

students with disabilities. Since limited studies exist about best practices in blended learning

for at-risk students, research on best practices within traditional or strictly online

environments could also be looked at and extrapolated to the blended learning environment

(Repetto & Spitler, 2014). Repetto, Cavanaugh, Wayer and Liu (2010) describe the factors

affecting completion rates for students with disabilities in terms of virtual high schools and

online education. Repetto and Spitler (2014) feel it is reasonable to assume these same factors

for engaging students with disabilities apply to a blended learning situation as well as

traditional learning.

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Repetto et. al. (2010) describe the importance of the 5C's in improving graduation

rates for students with disabilities. According to Repetto and Spitler (2014) the 5Cs are

"interrelated and influence each other in order to provide a learning environment, be it faceto-face, blended or online, equipped to support all students" (p. 115). The 5Cs as described by

Repetto and Spitler (2014) include:

students need to be able to connect current learning in school to the knowledge and skills they

will need post-school

students need to be provided with a safe and supportive climate for learning

students need to understand and learn how they are in control of their own learning and

behaviours

students need an engaging curriculum grounded in effective instructional strategies and

evidence-based practices to support their learning

students need to be part of a caring community that values them as learners, as well as

individuals. (p. 115)

These five supports (5 Cs) are necessary in improving at-risk student success. Outreach

schools will want to ensure any instructional shift toward blended learning addresses and

strengthens these 5Cs.

One 3-year case study of at-risk high school students working fully online points out

that students appreciate the opportunity to work ahead and study at their own pace but they

find it a challenge to be responsible for their own learning and manage their time (Lewis,

Whiteside & Dikkers, 2014, p.1). Lewis et. al. (2014) suggest that with proper support

structures in place, students who are at-risk for dropping out can overcome challenges and

find success in an online learning environment (p.1). One of the support structures Lewis et.

al. (2014) recommend is an individualized, face-to-face system that will support at-risk

students with project management skills, monitor the learning process and one-on-one

instructor tutoring. This is consistent with the 5Cs specifically the need to help students

understand and learn how they are in control of their own learning which was described

earlier as a key factor in improving at-risk student achievement.

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

The Sunchild E-Learning Community created a blended learning model that aligns

with Lewis et. al.s (2014) recommendations described above. The Sunchild E-Learning

Community program is a blended self-paced approach to providing First Nations students

access to quality education. Sunchild First Nation found that their students faced many

challenges including family and legal situations, time away from class and relocating to new

homes and many students were adults wanting to upgrade and build a better future while

meeting their current schedules and responsibilities (Vaughan, 2012, p.1). Mentors, to help

students with organizing, scheduling, community building and tutorials, are now placed in the

local learning centers to provide face-to-face support. Online teachers provide the same

students with synchronous classes, tutorials and asynchronous content specific supports

through a web-based learning management system and conferencing tools. Vaughan (2012)

describes all of these supports as the key to the academic success of students in the

program (p.12). This blended approach helped First Nations students overcome major

learning challenges such as remote locations, lack of access to digital technologies, high

speed internet access, and quality teachers (Vaughan, 2012, p. 12). The First Nations

students in this study face challenges similar to those faced by many of the students found in

Outreach schools.

The results of this study would also be valuable to Outreach schools in remote areas

or small schools where one or two teachers run the whole show. It is important to pay close

attention to some of the program concerns and recommendations described by Vaughan

(2012): roles and responsibilities of the online teacher in this program can become

overwhelming, the importance of creating a sense of community at the learning centers and

there is a need for solid communication and tight feedback loops between mentors, online

teacher and students (p.12).

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Vaughans recommendation, that face-to-face supports in the blended learning model

allow at-risk students to stay more on track with their learning, are consistent with the 5Cs

and with the findings from Bonds (2012) study on special needs students in a hybrid school

setting. Bonds (2012) study looks at different hybrid and online instructional models and

identifies five keys areas that are associated with high student achievement, these are; the

existence of differentiated instruction, the presence of highly qualified, experienced teachers,

the presence of a system of constant monitoring and accountability, providing students with

opportunities to demonstrate learning in various ways, and opportunities for students to

interact with peers and staff (Bond, 2012, abstract p.1).

Another study that specifically looks at at-risk students provides some warnings.

Turners (2015) small sample study of at-risk digital natives comparing a traditional

classroom environment to an online environment shows that, at-risk students who were

comfortable with technology, preferred face-to-face interaction to an online learning

experience. Turner warns that at-risk digital natives may be experts at using social media

and technologies to function daily, [but] there remains a desire for face-to-face interaction or

the traditional lecture-style delivery. (p. 61). However, he does point out that a preference

for face-to-face instruction delivery does not actually translate into a measurable impact on

learning and this should be an area for further research. It is interesting to note that the at-risk

students preference for face-to-face learning could be mediated through a blended learning

approach.

Conclusion

The Outreach school setting is a unique learning environment that a wonderful variety

of students choose to a take part in. Due to its uniqueness, flexibility and focus on supporting

at-risk student success, Outreach teachers are always looking for new instructional techniques

to engage students. Outreach schools already have in place the flexible attendance practices

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

that would allow a variety of different blended learning models to be set up. However, it is

important to keep in mind that most Outreach schools are small spaces that cannot physically

contain all registered students face-to-face at one time, creating a limit on the attendance

options. As discussed, the Flex Model, the Enriched Virtual or variations on these are most

relevant to the small, flexible Outreach school setting. The various models of blended

learning presented above, whether based out of traditional brick and mortar schools or small

alternative school buildings, provide a snapshot of the possibilities for blended model

variations. These model variations can help inform what a model of blended learning might

look like at an Outreach school. Ferdig, Cavanaugh & Freidhoff (2015) warn that there are

multiple models and that not every model is right for every situation, which only emphasises

the importance of exploring as many models as possible (p. 57).

The accolades and hopes for the future of blended learning have been presented

throughout this paper and as Akkoyunlu and Soylu (2008) advise, blended learning has all the

benefits of e-learning, including cost reductions, time efficiency and location convenience

for the learner as well as the essential one-on-one personal understanding and motivation that

face-to-face instruction presents," (p.184). But most importantly, the research on blended

learning also supports many of these same claims. Research shows that blended learning

improves student success - be it increased graduation rates or student achievement (Watson

et. al, 2014; Mattis, 2015; Kazu & Demirkol, 2014; Means et. al., 2013).

According to Ferdig et. al. (2015), no study can conclude definitively that online and

blended education is always better than brick-and-mortar or vice versa (p.54). However,

they do agree with the majority of studies discussed in this paper that blended education is

as good as and sometimes is better and sometimes worse than face-to-face education

(p.54). The key is to look at the student and to determine if the environment suits them. What

features are in place to help them be successful? The research shows that the face-to-face

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

component provides key supports for all students including the at-risk student (Vaughan,

2012; Akkoyunlu & Soylu, 2008; Whiteside & Dikkers, 2014). The marriage of online

formats with the face-to-face has been suggested to serve as a safety net for those at risk for

dropping courses and to fulfill the needs of students with specific delivery preferences

(Kassner, 2013, p. 6).

It is important to note that some researchers have taken research in online education

and extrapolated and applied it to the blended learning environment. Lessons can be learned

from research on online learning but it is important to keep in mind that the blended learning

environment is significantly different and, as noted in the authoritative meta-analysis by

Means et. al. (2013), it is more effective than online learning alone.

The focus of this study was to determine if blended learning could be used to improve

at-risk student success in an Outreach school setting. Some next steps for future research

would be to look deeper into the specific conditions that create the successful blended

learning environments for at-risk students. It was disappointing to see the limited empirical

research available on at-risk students, especially since these students make up a large

proportion of those found in blended learning environments (Barbour, 2009; Repetto &

Spitler, 2014). Due to the limited research on K-12 at-risk students specifically in blended

learning environments, more empirical studies must be performed before robust conclusions

can be formed. Hopefully research in this area will increase, specifically in the K-12

Canadian context.

Overall, the blended learning studies results suggest that a blended learning approach

could likely improve at-risk student achievement in Outreach schools. The recommendations

and suggestions provided by each of the studies are vital to create a successful program and

must play an integral part in any movement to develop a blended learning program in an

Outreach school.

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

References Cited

About Navigate Distributed Learning in BC. (2016). Retrieved from

http://www.navigatenides.com/about/index

Akkoyunlu, B., & Soylu, M. Y. (2008). A study of student's perceptions in a blended learning

environment based on different learning styles. Journal of Educational Technology &

Society, 11(1), 183-193. Retrieved from http://www.ifets.info.qe2aproxy.mun.ca/index.php?http://www.ifets.info.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/abstract.php?

art_id=827

Barbour, M. K. (2009). Todays student and virtual schooling: The reality, the challenges,

the promise. Journal of Distance Learning, 13, 525. Retrieved from

http://journals.akoaotearoa.ac.nz/index.php/JOFDL/index

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2014). State of the Nation: K-12 Online Learning in Canada.

Abbreviated edition. Canadian eLearning Network. Retrieved from

http://canelearn.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/StateOfTheNation2014.pdf

Bond, E. C. (2012). Program elements for special needs students in a hybrid school setting.

Retrieved from http://educationnext.org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/credit-recovery-hitsmainstream/

Bridges to Achievement. (n.d.). Retrieved from: http://argyll.epsb.ca/learning supports/bridges-to-achievement

Brown, M. R. (2000). Access, instruction, and barriers technology issues facing students at

risk. Remedial and Special Education, 21(3), 182-192. doi:

10.1177/074193250002100309

Carr, S. (2014). Credit recover hits the mainstream. Education Next, 14(3), 30-37.

Chang, C. C., Shu, K. M., Liang, C., Tseng, J. S., & Hsu, Y. S. (2014). Is blended e-learning

as measured by an achievement test and self-assessment better than traditional

classroom learning for vocational high school students? The International Review of

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2). Retrieved from

http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1030111

CWTA (2013). Facts & Figures. Retrieved June 14, 2015, from http://cwta.ca/facts-figures/

Dichev, C., Dicheva, D., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2013). Current practices, trends and

challenges in K-12 online learning. Cybernetics and Information Technologies, 13(3),

91-110.

Ferdig, R. E. (2010). Understanding the role and applicability of K12 online learning

to support student dropout recovery efforts. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual

University. Retrieved October, 18, 2012. Retrieved from

http://www.mivu.org/Portals/0/RPT_RetentionFinal.pdf

Ferdig, R.E., Cavanaugh, C., & Freidhoff, J. R. (2015). Research into K-12 online and

blended learning. In T. Clark & M. Barbour (Eds.), Online, blended and distance

education in schools: Building successful programs, (pp. 52 - 58). Virginia: Stylus

Publishing, LLC.

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems. CJ Bonk & CR Graham, The

handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs. Pfeiffer. Retrieved

from http://www.click4it.org/images/a/a8/Graham.pdf

Horn, M. B., & Evans, M. (2013). New schools and innovative delivery. Pathway to

success for Milwaukee schools, 16-27. Retrieved from

http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/-hornevans-new-schools-andinnovative-delivery_163046841296.pdf

Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2014). Blended: Using disruptive innovation to improve schools.

John Wiley & Sons.

Housego, B. E. (1999). Outreach schools: An educational innovation. Alberta Journal of

Educational Research, 45(1), 85. Retrieved from

http://ajer.journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ajer/article/view/26

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2015). NMC Horizon Report:

2015 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium. Retrieved from

http://www.eric.ed.gov.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?

accno=ED559357

Kassner, L. (2013). Mix It Up with Blended Learning in K12 Schools. Retrieved from

http://wp.vcu.edu/merc/files/2013/10/Blended-Learning-Report-9.13.131.pdf

Kazu, I. Y., & Demirkol, M. (2014). Effect of Blended Learning Environment Model on

High School Students' Academic Achievement. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal

of Educational Technology, 13(1). Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov.qe2aproxy.mun.ca/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ1018177

Kennedy, K., & Archambault, L. (2015). Bridging the Gap Between Research and Practice in

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

Online Learning. Journal of Online Learning Research, 1(1), 5-7. Retrieved from

http://www.editlib.org/p/149914/paper_149914.pdf

Lagana-Riordan, C., Aguilar, J. P., Franklin, C., Streeter, C. L., Kim, J. S., Tripodi, S.

J., & Hopson, L. M. (2011). At-risk students perceptions of traditional schools

and a solution-focused public alternative school. Preventing School Failure,

55(3), 105-114. doi:10.1080/10459880903472843

Lewis, S., Whiteside, A., & Dikkers, A. G. (2014). Autonomy and responsibility: Online

learning as a solution for at-risk high school students. Journal of Distance Education

(Online), 29(2), 1. Retrieved from http://www.ijede.ca.qe2aproxy.mun.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/883/1543

Longhurst, J. (2003). World History on the World Wide Web: A student satisfaction survey

and a blinding flash of the obvious. History Teacher, 343-356. Retrieved from

http://www.historycooperative.org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/journals/ht/36.3/

Mackey, K. (2010). Wichita public schools learning centers: Creating a new educational

model to serve dropouts and at-risk students. Innosight Institute, March. Retrieved

from http://www.christenseninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Wichita-PublicSchools-Learning-Centers.pdf

Mattis, K. V. (2015). Flipped classroom versus traditional textbook instruction: assessing

accuracy and mental effort at different levels of mathematical complexity.

Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 20(2), 231-248. http://dx.doi.org.qe2aproxy.mun.ca/10.1007/s10758-014-9238-0

McRae, P. (2015). Blended learning: The great new thing or the great new hype. 19-27.

Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answersheet/wp/2015/06/21/blended-learning-the-great-new-thing-or-the-great-newhype/This article was printed in the Summer

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online

and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers

College Record, 115(3), 1-47. Retrieved from

https://www.tcrecord.org/library/Abstract.asp?ContentId=16882

Najafi, H., Evans, R., & Federico, C. (2014). MOOC integration into secondary school

courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,

15(5). Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1045969

O'Hara, K., & Sellen, A. (1997). A comparison of reading paper and on-line documents. In

Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in computing

systems (pp. 335-342). ACM.

Patrick, S., Kennedy, K., Powell, A., & International Association for K-12 Online, L. (2013).

Mean What You Say: Defining and Integrating Personalized, Blended and

Competency Education. International Association For K-12 Online Learning

BLENDED LEARNING IN OUTREACH

(iNACOL). Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov.qe2aproxy.mun.ca/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED561301

Raymond, M. R., Smith, A., Johnson, K. & Glick, D. (2015). Ensuring equitable access in

online and blended learning. In T. Clark & M. Barbour (Eds.), Online, blended and

distance education in schools: Building successful programs, (pp. 71 - 81). Virginia:

Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Repetto, J., Cavanaugh, C., Wayer, N., & Liu, F. (2010). Virtual high schools: Improving

outcomes for students with disabilities. Quarterly Review of Distance Education,

11(2), 91. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/854554128?

accountid=12378

Repetto, J. B., & Spitler, C. J. (2014, January). Research on at-risk learners in K-12 online

learning. In R. E. Ferdig & K. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of Research on K-12

Online and Blended Learning, (pp. 107-134). ETC Press. Retrieved from

http://press.etc.cmu.edu/files/Handbook-Blended-Learning_Ferdig-Kennedyetal_web.pdf

Staker, H., & Horn, M. B. (2012). Classifying K-12 Blended Learning. Innosight

Institute. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED535180

Turner, M. M. (2015). Technologys impact on the learning experience of at-risk digital

natives. Retrieved from https://dspace.iup.edu/handle/2069/2437

Vaughan, N.D. (2012). A blended approach to Canadian First Nations education: The

Sunchild e-learning community. Retrieved from

http://www.ascilite.org/conferences/Wellington12/2012/images/custom/vaughan,_nor

man_-_a_blended_approach.pdf

Watson, J. (2008). Blended Learning: The Convergence of Online and Face-to-Face

Education. Promising Practices in Online Learning. North American Council for

Online Learning. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED509636

Watson, J., Pape, L., Murin, A., Gemin, B., Vashaw, L., & Evergreen Education, G. (2014).

Keeping Pace with K-12 Digital Learning: An Annual Review of Policy and Practice.

Eleventh Edition. Evergreen Education Group, Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?

id=ED558147

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Principal CollegeDocumento4 paginePrincipal CollegeAnusha Verghese50% (2)

- "Wonder Is The Feeling of A Philosopher, and Philosophy Begins in Wonder" - SocratesDocumento2 pagine"Wonder Is The Feeling of A Philosopher, and Philosophy Begins in Wonder" - SocratesAlfred AustriaNessuna valutazione finora

- South East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South CotabatoDocumento25 pagineSouth East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South CotabatoJan Edzel Batilo IsalesNessuna valutazione finora

- I Year B.a., Ll.b. (Hons)Documento3 pagineI Year B.a., Ll.b. (Hons)theriyathuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Counseling Psychologist: in APA Governance Members of The Society of Counseling Psychology Currently ServingDocumento4 pagineThe Counseling Psychologist: in APA Governance Members of The Society of Counseling Psychology Currently ServinganitnerolNessuna valutazione finora

- FY19 Feedback - Staff For Nikita JainDocumento2 pagineFY19 Feedback - Staff For Nikita JainVishal GargNessuna valutazione finora

- ForecastingDocumento23 pagineForecastingHarsh GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz 8.1 - Review - Correct Tense and Future Forms - Attempt ReviewDocumento7 pagineQuiz 8.1 - Review - Correct Tense and Future Forms - Attempt Reviewttestting002Nessuna valutazione finora

- Data Collection Sem OldDocumento62 pagineData Collection Sem OldAmy Lalringhluani ChhakchhuakNessuna valutazione finora

- Crucial Conversations 2Documento7 pagineCrucial Conversations 2api-250871125Nessuna valutazione finora

- CFA Level III in 2 Months - KonvexityDocumento6 pagineCFA Level III in 2 Months - Konvexityvishh8580Nessuna valutazione finora

- Brain CHipsDocumento17 pagineBrain CHipsmagicalrockerNessuna valutazione finora

- Flip Module 3D Page PDFDocumento110 pagineFlip Module 3D Page PDFPixyorizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tchokov-Gemiu - El PIano 2º MetodologíaDocumento5 pagineTchokov-Gemiu - El PIano 2º MetodologíaGenara Pajaraca MarthaNessuna valutazione finora

- Establishing A Democratic CultureDocumento9 pagineEstablishing A Democratic CultureGabriel GimeNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise Induced Neuroplasticity - Rogge 2018Documento38 pagineExercise Induced Neuroplasticity - Rogge 2018Juani Cantellanos0% (1)

- Syllabus: FOR (Compulsory, Elective & Pass)Documento61 pagineSyllabus: FOR (Compulsory, Elective & Pass)Jogendra meherNessuna valutazione finora

- The Wiser The BetterDocumento6 pagineThe Wiser The BetterDave DavinNessuna valutazione finora

- Arousal, Stress and AnxietyDocumento53 pagineArousal, Stress and Anxietykile matawuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Psychology of MoneyDocumento35 pagineThe Psychology of MoneyKeyurNessuna valutazione finora

- Healing & Spirituality (591 Books)Documento9 pagineHealing & Spirituality (591 Books)Viraat Sewraj100% (1)

- 1.1 - Understanding Context in Fiction AnsweredDocumento4 pagine1.1 - Understanding Context in Fiction AnsweredJoãoPauloRisolidaSilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 - Marisel Selene Gutierrez Garcia - Oxford Online Skills Program B1Documento9 pagine2 - Marisel Selene Gutierrez Garcia - Oxford Online Skills Program B1seleneNessuna valutazione finora

- Components of SW PracticeDocumento74 pagineComponents of SW PracticeIris FelicianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Age 16 Child Behavior Checklist External Site MM FinalDocumento6 pagineAge 16 Child Behavior Checklist External Site MM FinalSammy FilipeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hypothesis and Assumptions of The StudyDocumento12 pagineThe Hypothesis and Assumptions of The StudyMaria Arlene67% (3)

- Vishal Losho GridDocumento4 pagineVishal Losho GridKaushal JiNessuna valutazione finora

- ACCA Certified Accounting Technician Examination - PaperDocumento7 pagineACCA Certified Accounting Technician Examination - Paperasad27192Nessuna valutazione finora

- 10 10thsetDocumento2 pagine10 10thsetQuiquiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gnostic Anthropology: One of The Skulls Found in Jebel IrhoudDocumento3 pagineGnostic Anthropology: One of The Skulls Found in Jebel IrhoudNelson Daza GrisalesNessuna valutazione finora