Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Genre Analysis and World Englishes

Caricato da

fiorella_giordanoTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Genre Analysis and World Englishes

Caricato da

fiorella_giordanoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

d:/weng/16-3/we1.

3d 23/7/98 16:25 sj

World Englishes, Vol 16, No. 3, pp. 313319, 1997.

08832919

Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes

VIJAY K. BHATIA*

ABSTRACT: In recent years, discourse and genre analysis has established itself as an important field of

study within linguistics having implications for applied linguistics, especially in the teaching and learning of

languages, mass communication, writing research, language reform and a number of other areas related to

professional and academic communication. However, a more recent recognition of variation in the use of

English as a result of its global spread and use in the `outer' and the `expanding circles' (Kachru, 1992) has

given rise to concerns about the need and capacity of the presently used paradigms, frameworks and

methodologies in discourse and genre analysis to account for such a variation. Since English has

undoubtedly acquired the status of a world language, it is more than necessary that linguists of all

persuasions, whether interested in the issues of language acquisition, description, use or reform need to

adjust their vision, paradigms, frameworks or methodologies in order to be able to account for this global

variation in the use of English in the intra and international contexts. The main purpose of this special

volume is to address some of these issues arising from intercultural and cross-cultural perspectives on the

use of English as an international or world language.

APPLIED GENRE ANALYSIS

Genre analysis, though variously defined in recent literature (see Martin, 1985, 1993;

Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993; Berkenkotter and Huckin, 1995), is generally understood to

represent the study of linguistic behaviour in institutionalized academic and professional

settings. Instead of offering a linguistic description of language use, it tends to offer

linguistic explanation, attempting to answer the question, Why do members of specific

professional communities use the language the way they do? The answer requires input not

from linguistics alone, but equally importantly, from sociolinguistics and ethnographic

studies, psycholinguistics and cognitive psychology, communication research, studies of

disciplinary cultures and most importantly, insights from members of such specialist

communities, to name only a few. Taking communicative purpose as the key characteristic

feature of a genre, the analysis attempts to unravel mysteries of the artefact in question.

Genre analysis, thus, has become one of the major influences on the current practices in the

teaching and learning of languages to learners in specialist disciplines like engineering,

science, law, business and a number of others. By offering a dynamic explanation of the

way expert users of language manipulate generic conventions to achieve a variety of

complex goals associated with their specialist disciplines, it focuses attention on the

variation in language use by members of various disciplinary cultures. It concentrates

on at least four main aspects of genre acquisition that professional users seem to display

when they handle specialist genres. They include knowledge of the code, genre knowledge

associated with disciplinary cultures, sensitivity to cognitive structuring, and finally what

Berkenkotter and Huckin call the genre ownership, which gives professional writers

confidence to exploit generic knowledge to respond to familiar and novel rhetorical

contexts.

Let me very briefly elaborate on these four areas of concern.

* Department of English, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong. E-mail:

enbhatia@cityu.edu.hk

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

314

Vijay K. Bhatia

(1) Knowledge of the code

The knowledge of the code, of course, is a prerequisite to communicative expertise in any

specialist or even, everyday discourse. However, a perfect knowledge of the language is

neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to the acquisition of the genre.

(2) Genre knowledge

Participating in a specialist communicative event involves getting acquainted not only with

the communicative goals of a specialist discourse community, but also with the communicative purposes associated with specific use of genres to achieve those goals. Genre

knowledge as a form of `situated cognition,' is seen as inextricable from professional

writers' procedural and social knowledge (Berkenkotter and Huckin, 1995: 13). Expert

professional writers often display some degree of mastery over this kind of genre knowledge, which includes procedural knowledge (the knowledge of tools, methods and

interpretative framework typically used in a discipline) and social knowledge (in the

sense of familiarity with the rhetorical and conceptual context) before they can claim

ownership of these professional genres. As Fairclough (1992) points out, `. . . a genre

implies not only a particular text type, but also particular processes of producing,

distributing and consuming texts.'

(3) Sensitivity to cognitive structures

Every disciplinary culture has its own way of structuring knowledge. Expert professionals not

only have access to the goals of their community and the conventions associated with

specialist genres used by them, they also have explicit control over how these goals are

typically achieved in response to socio-cognitive demands in specific professional contexts.

They are sensitive not simply to the content of specific genres but also to the shapes that these

genres take in response to changes in social practices.

(4) Genre ownership

Good professionals own specialist genres; they know how to interpret them, use them, and

exploit them. They do not simply follow conventions, but often take liberties with them in

order to respond to familiar and not so familiar rhetorical contexts. In doing so, expert genre

writers, especially in the present-day contexts of ever-increasing consumer culture (Feathertone, 1991), often resort to what Bhatia (1995, 1997) refers to as genre-mixing and genre

embedding to achieve `private intentions' within the context of `socially recognized communicative purposes.'

Recent literature in applied genre analysis has shown increasing interest in the study of

generic variation as a result of diverse practices often associated with specific disciplinary

cultures; however, the discipline has paid very little attention to variation which may be the

result of two other kinds of diversity, one emerging as a result of the use of English as a

world language, and the other as a result of the cross-cultural and/or intercultural factors.

Let us turn our attention to these two.

Multicultural identity of English

English has, as a result of its global spread, over the years acquired identities which are

essentially multicultural. The consequence of this kind of participation, Kachru maintains

is that

. . . the spread of English has resulted in a multiplicity of semiotic systems, several nonshared

linguistic conventions, and numerous underlying cultural traditions. . . And, any speaker of

English (native or non-native) has access to only a subset within the patterns and conventions of

cultures which English now encompasses. . . . English has now become a medium of cross-cultural

expression and, one hopes, of intercultural understanding, too (Kachru, 1988: 207).

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes

315

We may or may not accept it, but it is a fact, more widely recognized now than a few years

ago, that there are significant variations in the use of English across national as well as

socio-cultural boundaries and that much of this kind of user-related variation has given

rise to the recognition and codification of many new varieties of English in the last few

years. It is also a fact that all these changes have not come as a complete surprise. They are

an inevitable result of the immense popularity and an overwhelming acceptance of the use

of English as the medium of communication in a variety of social, academic, occupational,

and other specialized areas of language use, some of which include business and trade,

science and technology, economics and finance, politics and diplomacy, newspapers and

advertising, computers and mass media.

One thing that stands out clearly from the foregoing is that the present-day use of

English is embedded within multilingual as well as multicultural contexts. As Quirk et al.

(1972) pointed out:

English, which we have referred to as a lingua franca, is pre-eminently the most international of

languages. Though the mention of the language may at once remind us of England, on the one

hand, or cause association with the might of the United States, on the other, it carries less

implication of political or cultural specificity than any other living tongue.

However, referring to the cultural diversity of the users of English, they cautiously add:

. . . the cultural neutrality of English must not be pressed too far. . . . The literal or metaphorical

use of such expressions as case law throughout the English speaking world reflects the common

heritage in our legal system; and allusions to or quotations from Shakespeare, the Authorized

Version, Gray's Elegy, Mark Twain, a sea shanty, a Negro spiritual or Beatles song wittingly or

not testify similarly to a shared culture. The continent means `continental Europe' as readily in

America and even Australia and New Zealand as it does in Britain. At other times, English

equally reflects independent and distinct culture of one or other of the English-speaking

communities. When an Australian speaks of fossicking something out (searching for something),

the metaphor looks back to the desperate activity of reworking and diggings of someone else in

the hope of finding gold that had been overlooked. When an American speaks of not getting to

first base (not achieving initial success), the metaphor concerns . . . (a)n equally culture-specificactivity the game of basketball. And when an Englishman says something is not cricket (unfair),

the allusion is to a game that is by no means universal in the English-speaking countries (Quirk et

al., 1972: 6)

Looking at it now, one is inevitably amazed at the universal popularity of baseball in

Japan and that of The Beatles and of cricket in many of the other English-speaking

countries. The English language, like cricket, has no longer remained the exclusive

property of a once great (cricketing nation) Britain. In fact, the strength of English lies

in the fact that it does not represent just one culture or one way of life alone, at least

not in its present form; it is being used as a vehicle for communicating several

cultures, several ways of conducting the business of science and technology, discussing

issues and negotiating realities in trade, commerce, management, economics and

politics.

Metamorphism of English

In the process of becoming a universal medium of communication, English language

itself has undergone gradual metamorphism, acquiring a number of additional identities,

in addition to several it has always enjoyed. Perhaps one of the important reasons, apart

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

316

Vijay K. Bhatia

from the obvious historical ones, for a greater acceptance of English as a world language

has been the relative ease with which the English language has accepted innovations,

additions and extensions, enriching itself in the bargain. A language is bound to be as

readily acceptable to outsiders as readily it accepts external influences. To the purist, it

may appear to be a great weakness, but considered in a wider global context, this very socalled `weakness' has become its greatest strength. As a natural consequence of its

immense popularity and global spread, English is increasingly becoming international

in character.

John Adams, the second president of the United States, predicted as early as 1780 that

English would be the most respectable language in the world and the most universally read

and spoken in the next century . . . (see Mathews, 1931, quoted in Kachru, 1992: 2). When

predicting such a spectacular rise in the use of English, he was, perhaps, unaware of the

fact that one day English itself will undergo transformation from the English of a

particular section of world population (British, American or Australian) to the English,

or more appropriately World Englishes.

Jacob Grimm, speaking to the Royal Academy of Berlin in January 1851, probably had

this thing in mind when he declared,

Of all modern language, not one has acquired such great strength and vigour as the English. It has

accomplished this by simply freeing itself from the ancient phonetic laws, and casting off almost

all inflections; whilst, from its abundance of intermediate sounds, tones not even to be taught, but

only to be learned, it has derived a characteristic power of expression such as perhaps was never

yet the property of any other human tongue. . . . Indeed, the English language, . . ., may be called

justly a LANGUAGE OF THE WORLD . . . (see Grimm [1851] 1965; quoted in Bailey, 1991:

109110).

The interesting point about Grimm's prediction is the importance he attaches to the

natural capacity of English in adapting and absorbing influences, changes and innovations, which he thinks are partly responsible for making English popular as a world

language. Today we do not need to make a case for the universal popularity and global

spread of English as a dominant medium of communication in almost every international

context, be it politics or business, trade or commerce, science or engineering, agriculture or

information science, radio or television, advertising or journalism. More recently, Kachru

(1991) confirms,

. . . English has acquired unprecedented sociological and ideological dimensions. It is now wellrecognized that in linguistic history no language has touched the lives of so many people, in so

many cultures and continents, in so many functional roles, and with so much prestige, as has

the English language since the 1930s. And, equally important, across cultures English has been

successful in creating a class of people who have greater intellectual power in multiple spheres

of language use unsurpassed by any single language before; (Kachru, 1991: 180).

Two things stand out very clearly from these assertions. First, that the rise of English to

stardom, as it were, is multifunctional rather than any particular restricted aspect of

general use, either social or professional. Second, it is embedded within multilingual as well

as multicultural contexts.

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes

317

MULTICULTURAL WORLD OF WORK

The working world is becoming increasingly multicultural as a result of the merger of

business organizations to form big multinationals to operate across national borders. In

this emerging context, it is misleading to assume that all professional activities are

conducted through English, whether British or American. Many of the multinationals

which operate offshore often recruit, wherever possible, a large number of employees, and

some key personnel from the host country. This helps them to handle, and avoid, if

possible, any linguistic, socio-ethnic, intercultural and cross-cultural constraints they may

be required to confront in the host country. Underlying this strategy, there seems to be a

clear understanding of the requirements of operating in a multicultural setting.

Even if we assume that English is the dominant mode of communication in such

professional contexts, it is still not true that all interactants need to be governed by a set of

uniform native standards. As Strevens (1992) points out, there are significant differences in

the way English is actually used globally. It often, he points out, involves linguistic

interactions of three types of participants: native speaker and native speaker (NS-NS);

native speaker and non-native speaker (NS-NNS); and, non-native speaker and non-native

speaker (NNS-NNS). The use of English in a majority of situations outside the native

contexts, be they academic or professional, may not always involve a native speaker as one

of the interactants. Even where a native speaker is involved as one of the interactants in

contexts outside the `inner circle' (Kachru, 1992), it is the responsibility of both the parties

to make effort to avoid misunderstanding and miscommunication arising from crosscultural factors in the use of language.

CHANGING LANGUAGE TEACHING CONTEXTS

One of the most influential models of communication that has influenced language

teaching in recent times has been associated with the notion of communicative competence,

which goes well beyond what linguists term as grammatical competence and includes what

could be broadly termed as sociolinguistic competence, which means the knowledge of

what is socially acceptable in real-life socio-cultural situations. In addition to these two

types of competence, one also needs a more selective and specialized kind of competence,

which could be termed as generic competence, which allows a person to choose from a

range of appropriate genres the one that is most suitable for achieving the communicative

purpose(s) in institutionalized social contexts.

Unfortunately, however, many of the language teachers interpret communicative

competence too narrowly to incorporate either the grammatical competence, or some

aspects of sociolinguistic competence in addition to that. It is important to note that these

various facets of competence may develop different patterns of proficiency and, may be, at

different rates. Of all the three, it is the grammatical competence which seems to be least

problematic for successful communication, in that it is still possible for people to be able to

communicate effectively even with a relatively less than desirable grammatical accuracy.

Sociolinguistic (in)competence, on the other hand, is likely to lead to more serious types of

miscommunication as well as misunderstanding. Generic competence, to a large extent, is

embedded in generic knowledge, which includes the experience or understanding of the

discursive practices associated with disciplinary cultures, and ensures pragmatic success in

communicative tasks embedded within specialized settings.

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

318

Vijay K. Bhatia

However, in the teaching and learning of languages, it is grammatical competence which

has traditionally been given the most important place. Sociolinguistic competence was

given quite a bit of importance in the 1980s as a result of the popularity of communicative

language methodology.

Generic competence, however, has become the focus of attention only recently as a

result of the somewhat unprecedented explosion of interest in genre-based studies of

discourse, where an attempt is made to answer the most important and yet often

overlooked question, `Why a particular text is written the way it is?' The main problem

with socio-cultural and strategic aspects of communicative competence is that they are

likely to be more generally embedded within the individual learner's socio-cultural

knowledge or experience of disciplinary cultures.

In the teaching and learning of English, especially ESP, the most important aspect of

learning is the acquisition of ability to use language in the context in which the learner is

or going to be part of. Learning a language, therefore, essentially involves a process of

contextualization. The context invariably involves the social semiotic within which the

learner is likely to operate. When English is taken from a native context and is

transported to a second language learning context, it carries with it the cultural baggage

of the native context.

So far as the learner's social semiotic is concerned, a great majority of ESP learners

across the globe are more likely to operate within their own native socio-cultural contexts,

rather than in any English-speaking native or even native-non-native context. As Steve

points out:

Foreign languages are usually taught with the goal of being able to communicate with/participate

in that language's `native' society. In this instance, it is necessary to teach the structure of the

language as well as the social semiotic as seen by the target culture. However, in most of the cases

in Asia and Africa, the goal is not to learn English to participate in the Anglo social semiotic, but

to transfer the native social semiotic on to the English base and thus nativize it as an effective

means of communication for that culture, without reference to the Anglo culture (Steve,

1994: 390).

The need, therefore, in most second language learning contexts is to transfer native social

semiotic to the second language, without being dictated to by the standards of the native

culture. In the emerging language learning and teaching contexts of variation in the use of

English across the international boundaries, it is necessary to recognize nativized norms

for intranational functions within specific speech communities, and then to build a norm

for international use on such models, rather than enforcing or creating a different norm in

addition to that. What needs to be done is that international English should be considered

a kind of superstructure rather than an entirely new concept. The best way this superstructure can be added is by making the learner aware of cross-cultural variations in the

use of English and by maximizing his or her ability to negotiate, accommodate and accept

plurality of norms. For language teaching pedagogy, as Kachru (1981: 37) points out, this

will require the use of a `dynamic' approach based on a polymodel concept rather than a

static monomodel approach to the teaching of professional communication. `Linguistic

homogeneity' as rightly pointed out by Kachru (1981: 26) `is the dream of an analyst, and a

myth created by the language pedagogues.'

Current work in applied discourse and genre studies has paid very little attention to

cross-cultural and intercultural variation resulting from a variation in the use of English

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

d:/weng/16-3/we1.3d 23/7/98 16:26 sj

Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes

319

globally. In order to cope with the rapidly increasing international mobility and the everchanging socio-political and economic influences on the use of discourse genres in the

changing context, I suggest we need to look more carefully and promote a more general

understanding of generic norms, suggesting accommodation, negotiation and plurality of

models, so that many of the second language learners' legitimate adaptations are seen as

exploitation of generic resources to reflect the meanings they assume, the social relations

they refer to, and the functions they seem to serve, rather than mere deviations. I hope that

contributions in the present volume will serve this purpose and add to the growing body of

literature in this area.

REFERENCES

Bailey, Richard W. (1991) Images of English: A Cultural History of the Language. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Berkenkotter, C. and Huckin, Thomas N. (1995) Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication Cognition/

Culture/Power. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bhatia, Vijay K. (1993) Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Longman.

Bhatia, Vijay K. (1995) Genre-mixing in professional communication the case of private intentions v. socially

recognized purposes. In Explorations in English for Professional Communication. Edited by Paul Bruthiaux, Tim

Boswood and Bertha Du-Babcock. City University of Hong Kong. pp. 119.

Bhatia, Vijay K. (1997) Genre-mixing in Academic Introductions. English for Specific Purposes, 16(3), 181195.

Fairclough, N. (1992) Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Featherstone, M. (1991) Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. London: Sage.

Kachru, Braj B. (1981) The pragmatics of non-native varieties of English. In English for Cross-Cultural

Communication. Edited by Larry Smith. London: Macmillan. pp. 539.

Kachru, Braj B. (1988) The spread of English and the sacred linguistic cows. In GURT 1987: Language Spread and

Language Policy: Issues, Implications and Case Studies. Edited by Peter Lowenberg. Washington DC:

Georgetown University Press.

Kachru, Braj B. (1991) World Englishes and applied linguistics. In Languages & Standards: Issues, Attitudes, Case

Studies. Edited by Makhan L. Tickoo. Singapore, RELC. pp. 178205.

Kachru, Braj B. (ed.) (1982, 2nd revised edition 1992) The Other Tongue: English across Cultures. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press.

Martin, J. R. (1985) Process and text: two aspects of human semiosis. In Systemic Perspectives on Discourse 1.

Edited by J. D. Benson and W. S. Greave. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. pp. 248274.

Martin, J. R. (1993) A Contextual Theory of Language. In The Powers of Literacy - A Genre Approach to Teaching

Writing. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 116136.

Quirk, Randolph, Greenbaum, Sidney, Leech, Geoffrey and Svartvik, Jan (1972) A Grammar of Contemporary

English. London: Longman.

Steve, Peter (1994) Norms and meaning potential. World Englishes, 13(3), 395410.

Strevens, Peter (1992) English as an international Language. In The Other Tongue: English across Cultures. (2nd

revised edition). Edited by Braj B. Kachru. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 2747.

Swales, John, M. (1990) Genre Analysis English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

(Received 15 June 1996.)

A Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Livro Writing Genres by Amy J. DevittDocumento261 pagineLivro Writing Genres by Amy J. Devittkelly_crisitnaNessuna valutazione finora

- World Englishes: ELF - English As A Lingua FrancaDocumento14 pagineWorld Englishes: ELF - English As A Lingua FrancaNoor KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Needs Analysis in Learning English For Airline Staff ProgramDocumento25 pagineA Needs Analysis in Learning English For Airline Staff ProgramRocco78100% (1)

- Littlewood - 2000 - Do Asian Students Vreally Want To ObeyDocumento6 pagineLittlewood - 2000 - Do Asian Students Vreally Want To ObeyHoanguyen Hoa NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- A Typology of The Prestige LanguageDocumento15 pagineA Typology of The Prestige Languageashanweerasinghe9522100% (1)

- Analyzing Written Discourse for ESL WritingDocumento16 pagineAnalyzing Written Discourse for ESL WritingMohamshabanNessuna valutazione finora

- Swales DiscoursecommunityDocumento8 pagineSwales Discoursecommunityapi-242872902Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing intercultural competence ethical issuesDocumento22 pagineAssessing intercultural competence ethical issuesDrAmany AlSabbaghNessuna valutazione finora

- Three Fundamental Concepts in SLA ReconceptualizedDocumento17 pagineThree Fundamental Concepts in SLA ReconceptualizedDr-Mushtaq AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation in Language Learning Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kamo Chilingaryan Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rimma GorbatenkoDocumento11 pagineMotivation in Language Learning Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kamo Chilingaryan Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rimma GorbatenkoAldrin Terrence GocoNessuna valutazione finora

- Language Identity and Investment in The PDFDocumento15 pagineLanguage Identity and Investment in The PDFAurora Tsai100% (1)

- Communicative Competence in Teaching English As A Foreign LanguageDocumento4 pagineCommunicative Competence in Teaching English As A Foreign LanguageCentral Asian StudiesNessuna valutazione finora

- Identity and Language Learning PDFDocumento12 pagineIdentity and Language Learning PDFEdurne ZabaletaNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of Sudan University of Sudan of Science and Technology College of Graduate StudiesDocumento13 pagineRepublic of Sudan University of Sudan of Science and Technology College of Graduate StudiesAlmuslim FaysalNessuna valutazione finora

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocumento9 paginei01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Reflections DescriptionDocumento1 paginaReading Reflections DescriptionKoustuv SahaNessuna valutazione finora

- De-Coding English "Language" Teaching in India: 57, No. 4. PrintDocumento9 pagineDe-Coding English "Language" Teaching in India: 57, No. 4. PrintSurya Voler BeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Language Research 1997 Bialystok 116 37Documento22 pagineSecond Language Research 1997 Bialystok 116 37Mustaffa TahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Esp-Week 2: Teguh Ardianto, M.PDDocumento25 pagineEsp-Week 2: Teguh Ardianto, M.PDTeguh ArdiantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Course OutlineDocumento5 pagineCourse OutlineRobert TsuiNessuna valutazione finora

- World Englishes Short QuestionDocumento5 pagineWorld Englishes Short QuestionNoorain FatimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Context in SLADocumento51 pagineSocial Context in SLAJunLibradillaMaloloy-onNessuna valutazione finora

- Doing Being Applied Linguists: The Importance of ExperienceDocumento13 pagineDoing Being Applied Linguists: The Importance of ExperienceSilmy Humaira0% (1)

- Critical Reading GuideDocumento5 pagineCritical Reading Guidetihomir40100% (2)

- A Cultural Semiotic Approach On A Romani PDFDocumento9 pagineA Cultural Semiotic Approach On A Romani PDFCristina Elena AndreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Beaugrande R., Discourse Analysis and Literary Theory 1993Documento24 pagineBeaugrande R., Discourse Analysis and Literary Theory 1993James CarroNessuna valutazione finora

- How Attitudes, Motivation and Language Aptitude Impact Second Language LearningDocumento21 pagineHow Attitudes, Motivation and Language Aptitude Impact Second Language LearningFatemeh NajiyanNessuna valutazione finora

- GardnerDocumento22 pagineGardnerAinhoa Gonzalez MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- c3109550 LING6030 Essay - FossilizationDocumento7 paginec3109550 LING6030 Essay - FossilizationSonia Caliso100% (1)

- Repetition PDFDocumento6 pagineRepetition PDFgeegeegeegeeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Difference Between Translation and InterpretingDocumento10 pagineThe Difference Between Translation and InterpretingMaisa TrevisoliNessuna valutazione finora

- 1997 Dornyei Scott LLDocumento38 pagine1997 Dornyei Scott LLtushita2100% (1)

- FAAPI-2014 - English Language Teaching in The Post-Methods Era PDFDocumento175 pagineFAAPI-2014 - English Language Teaching in The Post-Methods Era PDFfabysacchiNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 1. Intro To Stylistics PDFDocumento17 pagineModule 1. Intro To Stylistics PDFBryan Editor100% (1)

- English As A Lingua Franca EltDocumento3 pagineEnglish As A Lingua Franca EltNataly LeónNessuna valutazione finora

- Macrosocial Contexts of SlaDocumento8 pagineMacrosocial Contexts of SlaAyi Sasiah MNessuna valutazione finora

- Looking Under Kachru's (1982, 1985) Three Circles Model of World EnglishesDocumento39 pagineLooking Under Kachru's (1982, 1985) Three Circles Model of World EnglishesFranktoledoNessuna valutazione finora

- Metonymic Friends and Foes Metaphor andDocumento9 pagineMetonymic Friends and Foes Metaphor anddaniela1956Nessuna valutazione finora

- 002 Newby PDFDocumento18 pagine002 Newby PDFBoxz Angel100% (1)

- Teaching English as a Lingua FrancaDocumento9 pagineTeaching English as a Lingua Francaabdfattah0% (1)

- The International Corpus of Learner EnglishDocumento10 pagineThe International Corpus of Learner EnglishAzam BilalNessuna valutazione finora

- James Annesley-Fictions of Globalization (Continuum Literary Studies) (2006)Documento209 pagineJames Annesley-Fictions of Globalization (Continuum Literary Studies) (2006)Cristina PopovNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding English as a Lingua Franca: A ReviewDocumento7 pagineUnderstanding English as a Lingua Franca: A ReviewVoiceHopeNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine English CharacteristicsDocumento3 paginePhilippine English CharacteristicsChristine Breeza SosingNessuna valutazione finora

- ESP Technical SchoolDocumento11 pagineESP Technical Schoolfarah_hamizah12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching pragmatic competence of complimentsDocumento10 pagineTeaching pragmatic competence of complimentskayta2012100% (1)

- AMTB TechnicalManualReportDocumento26 pagineAMTB TechnicalManualReportKevin Trainor100% (1)

- Focus On Form by FotosDocumento7 pagineFocus On Form by FotosjuliaayscoughNessuna valutazione finora

- Contrastive Linguistics and Linguistic TypologyDocumento18 pagineContrastive Linguistics and Linguistic TypologyBecky BeckumNessuna valutazione finora

- Emergence of World Englishes ELTDocumento10 pagineEmergence of World Englishes ELTFrancois TelmorNessuna valutazione finora

- Fishman-Advance in Language PlanningDocumento2 pagineFishman-Advance in Language PlanningAnonymous YRLLb22HNessuna valutazione finora

- The Circuit of Culture, Discourse Analysis andDocumento18 pagineThe Circuit of Culture, Discourse Analysis andGavin Melles100% (8)

- TESOL Quarterly (Autumn 1991)Documento195 pagineTESOL Quarterly (Autumn 1991)dghufferNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Lanka School Textbooks Must Adopt Multiculturalism To Start PeaceDocumento5 pagineSri Lanka School Textbooks Must Adopt Multiculturalism To Start PeacePuni SelvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Mathematics in English To Vietnamese 6th GradeDocumento5 pagineTeaching Mathematics in English To Vietnamese 6th Gradeha nguyen100% (1)

- Intro to Discourse AnalysisDocumento18 pagineIntro to Discourse AnalysishljellenNessuna valutazione finora

- Pang 2003Documento7 paginePang 2003api-19508654Nessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphor in EapDocumento9 pagineMetaphor in Eapapi-323237776Nessuna valutazione finora

- Communicative Language TeachingDocumento7 pagineCommunicative Language TeachingCamelia GabrielaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignDa EverandAn Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Leadership Practice QuestionsDocumento15 pagineNursing Leadership Practice QuestionsNneka Adaeze Anyanwu0% (2)

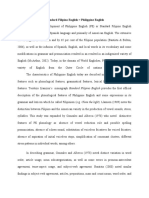

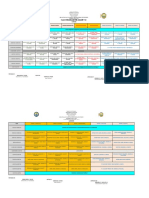

- Class Program For Grade 7-10: Grade 7 (Hope) Grade 7 (Love)Documento2 pagineClass Program For Grade 7-10: Grade 7 (Hope) Grade 7 (Love)Mary Neol HijaponNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Resource Action PlanDocumento2 pagineLearning Resource Action PlanTiny100% (17)

- HyponymyDocumento3 pagineHyponymysankyuuuuNessuna valutazione finora

- Navigating The Complexities of Modern SocietyDocumento2 pagineNavigating The Complexities of Modern SocietytimikoNessuna valutazione finora

- How Societies RememberDocumento27 pagineHow Societies RememberCatarina Pinto100% (1)

- Building Your Dream Canadian 10th Edition Good Solutions ManualDocumento28 pagineBuilding Your Dream Canadian 10th Edition Good Solutions ManualAngelaKnapptndrj100% (16)

- CRM Final Ppt-6Documento21 pagineCRM Final Ppt-6Niti Modi ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpersonal Communication in Older Adulthood - Interdisciplinary Theory and Research 1994, SAGEDocumento281 pagineInterpersonal Communication in Older Adulthood - Interdisciplinary Theory and Research 1994, SAGERubén JacobNessuna valutazione finora

- Assam Govt Job Vacancy for Asst Skill Project ManagerDocumento1 paginaAssam Govt Job Vacancy for Asst Skill Project ManagerNasim AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Automate Lab Management & Secure Student DataDocumento3 pagineAutomate Lab Management & Secure Student DataathiraiNessuna valutazione finora

- 2-Predicting The Role of Emotional and Behavioral Problems On Delinquent Tendencies in AdolescentsDocumento21 pagine2-Predicting The Role of Emotional and Behavioral Problems On Delinquent Tendencies in AdolescentsClinical and Counselling Psychology ReviewNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily English Phonics Lesson PlanDocumento20 pagineDaily English Phonics Lesson PlanKuganeswari KanesanNessuna valutazione finora

- AP Bio COVID Assignment 2Documento4 pagineAP Bio COVID Assignment 2Raj RaghuwanshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Required Officer Like Qualities OLQs For Passing SSB InterviewsDocumento2 pagineRequired Officer Like Qualities OLQs For Passing SSB InterviewsSaahiel SharrmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interprofessional Health Care TeamsDocumento3 pagineInterprofessional Health Care TeamsLidya MaryaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Sir Mokshagundam VisweswaraiahDocumento15 pagineSir Mokshagundam VisweswaraiahVizag Roads100% (5)

- Annoying Classroom DistractionsDocumento11 pagineAnnoying Classroom DistractionsGm SydNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Theories FinalDocumento5 pagineLearning Theories FinalJeo CapianNessuna valutazione finora

- Relationship Among Theory, Research and PracticeDocumento16 pagineRelationship Among Theory, Research and PracticeLourdes Mercado0% (1)

- Highly Gifted Graphic OrganizerDocumento2 pagineHighly Gifted Graphic Organizerapi-361030663Nessuna valutazione finora

- Data Mining Crucial for Targeted MarketingDocumento6 pagineData Mining Crucial for Targeted Marketingsonal jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction to Contract Management Framework WorkshopDocumento23 pagineIntroduction to Contract Management Framework WorkshopAdnan Ahmed100% (1)

- Cot English 4 1ST QuarterDocumento5 pagineCot English 4 1ST QuarterJessa S. Delica IINessuna valutazione finora

- Silver Oak College of Engineering and Technology Laboratory ManualDocumento27 pagineSilver Oak College of Engineering and Technology Laboratory ManualBilal ShaikhNessuna valutazione finora

- Institute of Graduate Studies of Sultan Idris Education University Dissertation/Thesis Writing GuideDocumento11 pagineInstitute of Graduate Studies of Sultan Idris Education University Dissertation/Thesis Writing GuideNurul SakiinahNessuna valutazione finora

- Parents Magazine Fall 2012Documento36 pagineParents Magazine Fall 2012cindy.callahanNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonology 2Documento11 paginePhonology 2vina erlianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 Slides - 1635819841573Documento16 pagineChapter 4 Slides - 1635819841573Dead DevilNessuna valutazione finora

- EQ Mastery Sept2016Documento3 pagineEQ Mastery Sept2016Raymond Au YongNessuna valutazione finora