Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Amayo Edu690 Actionresearchreport

Caricato da

api-305745627Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Amayo Edu690 Actionresearchreport

Caricato da

api-305745627Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Running Head: IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

The Impact of Reading Workshop on Student Reading Ability and Motivation to Read

Amanda J. Mayo

EDU 690

December 14th, 2015

University of New England

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Abstract

In this action research study, the researcher implemented a reading workshop

instructional model, utilizing the Units of Study in Reading (Calkins, 2015) unit Building a

Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan 2010) with a class of nineteen fifth grade students. The purpose

of this study was to determine whether implementing the reading workshop curriculum would

increase student achievement in reading as well as students motivation to read. This mixed

methods study collected multiple data sources to measure reading ability and motivation to read,

with the hopes of gaining an accurate picture of student growth in both these areas. Within this

five-week intervention window, the researcher saw significant growth in her students reading

ability and enthusiasm towards reading. While the majority of the data sources used to gauge

student progress agreed that significant growth had occurred, not all of the assessments saw the

same level of results. This disagreement in data limits the researchers ability to determine

exactly how much growth in reading ability occurred. Increased student motivation to read was

also seen during this study. Due to the positive results gathered, the researcher is confident that

the implementation of this instructional strategy successfully improved both student reading

achievement and motivation to read.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Table of Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5

Problem Statement ...................................................................................................................... 5

Research Questions ..................................................................................................................... 6

Hypothesis................................................................................................................................... 6

Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7

Reading Workshop Model .......................................................................................................... 7

Independent Reading .................................................................................................................. 9

The Importance of Student Choice ........................................................................................... 10

Effect on Reading Ability ........................................................................................................ 11

Effect on Motivation ................................................................................................................. 12

Ability's Effect on Motivation ................................................................................................. 13

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 14

Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 14

Research Design........................................................................................................................ 15

Data Collection Plan ................................................................................................................. 16

Student reading ability.. ........................................................................................................ 16

Student reading engagement. ................................................................................................ 18

Accuracy of results.. ............................................................................................................. 18

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Data Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 20

Sample Selection ....................................................................................................................... 21

Results ........................................................................................................................................... 23

Findings..................................................................................................................................... 23

Discussion ................................................................................................................................. 30

Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 34

Summary and Further Research ................................................................................................ 35

Action Plan.................................................................................................................................... 36

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 37

References ..................................................................................................................................... 39

Appendixes ................................................................................................................................... 47

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

The Impact of Reading Workshop on Student Reading Ability and Motivation to Read

This Action Research project studied the impact of the implementation of the Units of

Study (Calkins, 2015) unit Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010) on a fifth grade

classroom. Nineteen fifth graders between the ages of 10 and 11 were a part of this study which

occurred within their regular reading instruction during the fall of 2015. Students entered this

fifth grade classroom with varied reading instruction experiences, reading abilities, and levels of

motivation.

The school in which this study took place was planning to implement the Units of Study

curriculum, a curriculum that utilizes a focused reading workshop model, during the 2016-2017

school year. Prior to school-wide implementation, administrators were looking for classroom

teachers in each grade level to pilot the program during the 2015-2016 school year. Pilot teachers

were asked to utilize the program and determine what resources and supports would be needed

the following year when the entire school would begin using it. The researcher involved in this

study joined the pilot program in the hopes that utilizing the curriculum would increase both

student reading levels and student engagement in reading activities.

Problem Statement

Baseline data showed students in the class reading between a Level P and Level V, using

the Teachers College Running Record assessment (Teachers College Reading and Writing

Project, 2014). These same students showed just as wide of a range in desire to read both in

school and independently. The researcher observed that many students who read at belowexpected levels avoided independent reading tasks and reported that they did not enjoy reading.

Many students who were reading below the expected guided reading level for their grade (Level

T at this school), were also unmotivated to read based on an informal survey of reading interest.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

This study aimed to give students strategies and experiences with reading to make reading an

easier and more enjoyable task.

Research Questions

As the researcher noticed the lack of motivation to read occurring in her classroom, she

considered whether motivation to read increased along with ability to read. The main focus areas

of this research project were to discover; 1) did reading mini-lessons and increased reading

practice in class lead to stronger reading skills? And 2) did the lessons found in the first unit of

the Units of Study curriculum; Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010), lead to more

engaged and enthusiastic readers?

Hypothesis

The researcher believed that utilizing this reading workshop unit would lead to an

increase in student achievement. At the school in which this study took place, a fifth grade

student is expected to progress by one reading level per 12-week trimester. Following this fiveweek unit, growth of at least one reading level was expected. Students who were reading below

grade level expectations were expected to make increased progress towards the grade-level goal

of reading at a level T. It was also hypothesized that as an increase in student achievement

occurs, student self-proclaimed motivation and enjoyment in reading would also increase.

This action research report focuses on the impact of implementing the reading workshop

teaching model found in the Building a Reading Life unit (Calkins & Tolan, 2010).The following

Literature Review synthesizes the available research on reading workshop teaching models. The

Methodology section utilizes that research to design a method of collecting and analyzing data to

showcase the impact of the action research intervention as reported in the Results section.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Literature Review

Reluctant readers are usually struggling readers, and the cycle of avoiding reading leads

to a lack of growth in skills which leads to further avoidance. While there are many strategies

and instructional methods aimed at increasing reading ability and student motivation to read, few

facilitate both while fostering life-long readers. This action research project was focused on

improving student literacy skills and motivation to read through the implementation of a reading

workshop model of instruction. Existing research about the reading workshop model and its

components shows that it is indeed a reading instructional strategy that has many benefits for

students and can help create independent readers who love to read.

Reading Workshop Model

According to Meyer (2010), Reading workshop is a term that initially referred to reading

sessions that encouraged and supported the independent reading of literature (Atwell, 1987,

1998; Lause, 2004). (p.501). Most forms of reading workshop are comprised of several major

components which primarily include minilessons, independent reading, and sharing/response

time (Meyer, 2010, p. 501; Towle, 2000, p.39; Calkins & Tolan, 2010, p. VIII). Classes start out

gathered together for a focused minilesson led by the teacher. They then disassemble to read

independently for a period of time, often with the mission of utilizing a strategy taught in the

minilesson to guide their reading and/or thinking that day. At the end of the reading period,

students gather in pairs, small groups, or even as a whole class to discuss their reading,

implementation of the strategy or to consider something else about their reading lives (Calkins &

Tolan, 2010, p. VIII).

One of the biggest differences in a reading workshop classroom versus a traditional reading

classroom is the amount of direct instruction a teacher offers (Beers, 2003, p. 59). In a traditional

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

classroom, the majority of reading instructional time may be spent on reading-related tasks such

as whole-group discussion of a text, responding to questions, or competing worksheets. In a

reading workshop classroom, the reading instruction is a short, often less than 15 minutes, lesson

focused on a specific strategy or activity that students will complete during or after their

independent reading time (Beers, 2003, p. 59; Calkins & Tolan, 2010).

Another major difference is in the texts students are reading. In a traditional reading

classroom, students are usually reading teacher-selected texts as a whole class or in small groups.

While that can have its place, its not meeting the individual reading needs of students. Even in

the rare case that all students are reading at approximately the same level, each student has his or

own strengths and needs (Towle, 2000, p. 38) and those needs can best be met through

individual book selection. Kylene Beer sums it up perfectly in her book, When Kids Cant Read:

What Teachers Can Do (2003); In a workshop environment, students read different texts at

different rates and respond to those texts in a multitude of ways. They write in response to what

theyve read so that the reading-writing connection is reciprocalone informs the other (p.58).

Due to the individualized nature of reading workshop, assessment is usually done on an

individual basis involving one-on-one or small group conferences held during independent

reading time through which students strengths and needs can be determined (Towle, 2000, p.40)

and learning plans to meet those needs created. Assessment is primarily informal and ongoing as

a teacher thoroughly gets to know his/her students as readers. Some more structured reading

workshop models, such as Lucy Calkins and Kathleen Tolans Building a Reading Life (2010)

utilize whole-class pre- and post-assessments as a part of each workshop unit.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Independent Reading

Crucial to the reading workshop model is the philosophy that students need to read. In

most reading workshop models, students spend 30-60 minutes of class time a day individually

reading a book that is at their independent reading level. According to Allington (2012), In a

study across an international sample of schools, Elley (1992) reported a strong positive

relationship between teacher reports of time allocated to silent reading in their classrooms and

reading comprehension proficiency of their students (p. 48). Miller and Higgins (2008) agree

with this sentiment stating that in this independent reading time students engage in the amount

of reading that is necessary for continual improvement (Calkins 1991). (p.125).

More reading appears to correlate with greater reading ability. More time available

during the school day to read means more overall time spent reading. For some students, reading

time in school is the only time during their day that they will read. Miller and Higgins (2008)

assert that Most students find little or no time to read outside of school, time must be provided

in class (Tompkins 2006) (p.125).

This in-school reading time is especially important for struggling readers as The average

higher-achieving students read approximately three times as much each week as their lowerachieving classmates, not including out-of-school reading (Allington, 2012, p. 45). Some of this

additional reading time afforded to higher-achieving students comes from allowing them to focus

in class on actual reading tasks while lower-achieving readers receive more direct instruction

(and therefore less actual reading time). Higher-achieving students spent approximately 70

percent of their instructional time reading passages and discussing or responding to questions

about the material they read. By way of contrast, the lower-achieving readers spent roughly half

as much time on these activities (37 percent), with word identification drill, letter-sound

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

10

activities, and spelling and penmanship activities occupying large blocks of lesson times

(Allington, 2012, p.45). Miller and Higgins (2008) further this sentiment, saying that often

potential reading time is filled with listening to the teacher, completing worksheets, and waiting

for other students to complete similar tasks. These activities reduce the amount of time that less

effective readers actually spend reading independently (p. 125). Rather than less time spent

reading, struggling readers really need more. According to Allington (2012), struggling fourthgraders may need at least as much as 3 to 5 hours a day of successful reading practice to ever

hope to catch up with their more proficient peers (p.46). While giving students 3-5 hours of class

time to read independently is not feasible, utilizing the majority of reading instructional time for

actual reading is a first step in giving all readers the opportunity to grow and improve their skills.

The Importance Student Choice

Along with the importance of independent reading comes the importance of student

choice. Students involved in a reading workshop classroom have choices to make about what

genres, authors, and types of texts they will read. They often also have choice about where they

sit in the classroom during their independent reading and sometimes choices about the readingrelated tasks that they will complete. According to Anderman and Anderman (2014); intrinsic

motivation is enhanced when students are able to make choices (p.138). By giving students the

tools and the opportunities to self-select reading texts, reading workshop teachers are allowing

students to enjoy reading at a level that is not possible when all students are reading the same

text, or when book selection is made by the teacher.

Choice also leads to higher achievement; when students believe that they do have control

over their own outcomes, they are more likely to prefer challenging tasks, set higher goals for

themselves, and persist when faced with difficulty (Skinner et al., 1998) (Anderman &

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

11

Anderman, 2014, p. 139). The effect of choice is almost as influential in the success of students

reading as the availability of interesting texts (Allington, 2012, p. 73). Students who are able to

make decisions about their reading and learning are more likely to become invested in learning

activities and therefore put forth more effort into their work.

Effect on Reading Ability

As time spent reading leads to growth in reading skills and ability, and the reading workshop

model heralds independent reading time as a pillar of its structure; concluding that implementing

a reading workshop model will lead to increased reading ability seems a fair assumption to make.

As Miller and Higgins (2008) write; The amount of time provided for sustained, silent reading

in reading workshop, usually 30-60 minutes daily, enables students to gain information about the

world, acquire more vocabulary, and become familiar with sentence structure, thereby enabling

them to build the comprehension that is necessary to deal effectively with standardized reading

tests (Gillett et al. 2004) (p. 125). The question remains as to whether its the increased

independent reading time that is increasing these skills, or a combination of focused minilessons, independent reading time, and conference with a teacher that leads to these gains.

Many teachers who have adopted a reading workshop model have attested to the increases

they see in student reading ability. For some teachers, this means that they observe students

further engaging with a text and are able to reach deeper levels of thinking and engagement

with texts and greater input into and ownership of their learning (Meyer, 2010, p. 506). Swift

(1993) states that her weakest readers are the ones who made the most gains when using this

teaching method (p.370). Miller (2009) encourages the method by saying that she realized that

every lesson, conference, response, and assignment [she] taught must lead students away from

[her] and toward their autonomy as literate people (p.16). Regardless of what constitutes

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

12

increased reading ability to a particular teacher, its apparent that student growth occurs through

the use of this teaching method.

Effect on Motivation

Another key component to student success in reading is motivation. Motivation determines

whether and how well tasks are done both in and outside the classroom. Motivation has been

studied as one factor that impacts students learning to read, reading engagement, and reading

comprehension (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000) (Wolters et al., 2014, p. 504). Wolters et al. (2014)

cited several studies that showed interventions designed to improve childrens reading also have

been proven more effective if they include efforts to sustain or improve students motivation

(Guthrie, McRea, & Klauda, 2007) (p. 504). The link between motivation and reading success

has been proven time and again.

Students who are motivated to read, and read often, are more successful in their reading

attempts and therefore continue to put effort into reading. Donalyn Miller (2009) makes an

excellent point when she writes Many children dont read. They dont read well enough; they

dont read often enough; and if you talk to children, they will tell you that they dont see reading

as meaningful in their life (p.2). Failing to see reading as a meaningful and worthwhile activity

can mean that students avoid reading or do not read with the attention and mental effort required

for deep understanding.

Reading workshop teachers cite the reading workshop method of instruction as improving

students attitudes towards, and enjoyment in, reading (Swift, 1993, p.367). When asked about

their experience in reading workshop, students in Swifts (1993) Reading workshop classroom

regardless of reading level, or initial attitude towards reading, told [her] to keep reading

workshop (p.367). Many of those same students stated that reading workshop was the reason

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

13

they now enjoyed reading, after not enjoying it in the past (Swift, 1993, p. 367). By helping

students become more engaged and personally invested in their own reading, reading workshop

models make reading a more enjoyable activity.

Abilitys Effect on Motivation

When looking at the impact of reading workshop on both reading ability and motivation to read,

it makes sense to also look at the effect of reading ability on motivation and vice versa.

Inherently, people tend to avoid tasks that are particularly challenging or that have been

unsuccessful in the past. Reading is no different. As Wolters et al. (2014) state there are clear

reasons as to why less skilled students may hold different motivational beliefs than their higher

achieving peers. Struggling readers had, by definition, had repeated experiences of difficulty and

failure with regards to reading tasks, or in subject areas that rely heavily on literacy skills (p.

506). These are the students who have lower reading comprehension skills, less fluency with

their reading, and who are therefore more likely to find reading more challenging than other

students (Wolters et al., 2014, p. 523).

Reading workshop is great for students of all ability levels, but particularly lowerachieving students who need more time engaged in reading. These students also benefit greatly

from the choice of reading texts research has shown that these readers tend to express lower

levels of perceived control over reading tasks and were more likely to report feeling anxious

about reading (Wolters et al., 2014, p. 523). By giving students more control over their reading,

teachers utilizing a reading workshop model can help struggling students see more success in

reading and start to enjoy it.

Another great benefit for struggling readers that is inherent in the workshop model is that

they are able to read texts that are appropriate for their reading ability, read those tasks at their

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

14

own pace, and respond to those texts in different ways (Beers, 2003, p. 58). There is no one size

fits all mentality in reading workshop which is beneficial to all students as they read and write

about their reading.

Summary

In looking closely at the available research regarding reading workshop and its effect on

student achievement and motivation to read, it is clear that many teachers have had success in

implementing the model. The combination of choice, self-selected independent reading time, and

focused mini-lessons appears to be a successful model to help students gain confidence and skills

in their reading, as well as to learn to enjoy and seek out reading opportunities. In analyzing the

available research, the researcher was able to determine that implementing a reading workshop

model in her classroom would be beneficial to all students, but especially to the students who

struggled to read or for whom motivation to read was lacking. The hypothesis that students

engaged in a reading workshop classroom would make growth in their reading ability

(determined by running record (Teachers College, 2014) and STAR assessment scores) and

student motivation to read (determined by student survey and number of books read), appears to

be more valid than ever.

Methodology

In order to address the issue of lower motivation to read in students performing below

grade-level expectations in reading, the researcher decided to implement Calkins and Tolans

unit Building a Reading Life (2010)a reading workshop unit that focuses on students engaging

in meaningful reading and includes a lot of student choice about when, where, and what to read.

In implementing this unit, the researcher hoped to determine whether reading mini-lessons and

increased reading practice in class led to stronger reading skills. Additionally, the researcher

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

15

hoped to determine whether the lessons found in the first unit of the Units of Study curriculum;

Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010), led to more engaged and enthusiastic readers.

Based on the available research on the effectiveness of the reading workshop method of

instruction, the researcher hypothesized that students would make increased progress towards the

grade-level goal of reading at a Teachers College (2014) Running Record level of T. It was also

hypothesized that as student achievement in reading ability increased, students self-proclaimed

motivation and enjoyment in reading would also increase.

In order to determine whether the reading workshop strategy effectively met students

needs, a mixed-methods research method was designed in which data from formal and informal

assessments as well as student surveys was collected and analyzed in order to determine growth

in ability and motivation. This method was selected in order to obtain quantitative data about

student reading ability as well as qualitative data about how students feel about reading and

whether they are motivated to read when not required to do so.

Research Design

The Building a Reading Life unit comprises of 20 lessons about relevant reading topics

designed for third through fifth grade students. Each lesson begins with a mini-lesson where a

strategy, process, or skill is introduced, explained, and modeled to students. Students then take

that strategy, process, or skill with them during their independent reading time. This time is

intended to be 30-60 minutes. Due to the scheduling of the reading instructional period at this

school, independent reading time consisted of 30-40 minutes a day for this study. Within the 3040 minutes of independent reading, there was often a 2-3 minute Mid-Lesson Teach, a part of the

program where additional information pertaining to the strategy was given or where students

were reminded of what they were expected to be doing while they read that day. At the end of

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

16

the independent reading period was a brief 5 minute share section of the lesson where students

might work with a partner, small group, or even the whole class to discuss what worked well for

them during their independent reading or to reflect on the skill they were practicing that day.

For the purposes of this research project, the researcher attempted to adhere as closely as

possible with the program. The researcher utilized classroom structures and routines as described

in the unit. However, due to timing concerns or observations regarding student mastery of skills,

some lessons or strategies were afforded multiple days and/or reteaching moments as needed.

Data Collection Plan

Initial data that led to the development of this action research project showed that

students reading below a level T (the fifth grade expected reading level at this school) were often

students who avoided reading tasks or who did not appear to enjoy reading. The researcher

observed these below-expectation level students complaining about reading, having difficulty

selecting appropriate books, and overall lacking enthusiasm to read. To test the hypothesis that

implementing a reading working model would improve both student reading ability and

motivation to read, the researcher collected data regarding student reading level before and after

the intervention, as well as data regarding student engagement and enthusiasm towards reading

before and after the intervention. In order to collect data on both topics, several forms of data

collection occurred; STAR assessment, running records, number of books read, and a student

survey.

Student reading ability. To determine reading ability, this study used the Teachers

College Reading and Writing Project running record assessment (Appendix A) and the STAR

Reading Assessment. The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project running record is an

individualized assessment that analyzes both students fluency and comprehension. Students read

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

17

100 words of a leveled text aloud, and then read the remainder of the text selection to

themselves. Students are able and encouraged to reread the oral section of the text after they

finish. Fluency is determined in two ways; number of errors and on a fluency scale. The number

of errors is determined by calculating the number of oral reading errors made while reading 100

words. The number of self-corrections made to correct errors is also included in the calculation

of a students overall accuracy score (based on 100 per cent). Students are then scored on a fourpoint Oral Reading Fluency Scale (Appendix A, p. 45) which looks at the phrasing, expression,

and pacing of their oral reading.

Students are then asked to retell or summarize the story that they read. Based on the

quality of their summary, they may be asked to answer four comprehension question about the

sample text they read (Appendix A, p.46). Some students will include the answers to the question

within their summary, and therefore do not need to be asked again. Questions for each level of

running record include both literal and inferential questions.

In order for a student to be considered to be proficient at a certain reading level, they

must meet three criteria: 1) text is read with at least a 96% accuracy rate 2) student scores a 3 or

4 on the Oral Reading Fluency Scale and 3) student demonstrates both literal and inferential

comprehension through a combination of retell and responses. If these three criteria are met with

ease, the next level of running record should be attempted until the student no longer meets the

criteria. When this occurs, the previous level of competency is considered a students

independent reading level.

Another form of assessing student reading ability in this study was the STAR reading

assessment data (Renaissance Learning, 2015). Students at the school are expected to take the

STAR Reading assessment at least three times a year as a universal screener for academic

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

18

interventions. The STAR assessment is a computer-based assessment that increases and

decreases the level of difficulty of questions based on student performance. Assessment reports

include an overall Scaled Score, Grade Level Equivalent, and information for teacher on the

appropriate text levels students should be engaged with in order to reach desired growth. Grade

Level Equivalent scores generated by this assessment were utilized to compare pre- and postintervention growth in the sample selection for this project.

Student reading engagement. The Student Survey (Appendix B) regarding student

engagement and enjoyment in reading tasks was administered to the entire sample selection at

the same time via a Google Forms document. The survey asked students about whether they

choose to read in their free time, how they feel about reading, and how they would describe

reading. The information from this survey was used to gauge students overall attitudes towards

reading. Along with the survey, reading engagement was measured through a tally of the number

of books students read during the month before the intervention and during the month of data

collection. It was hypothesized that as students become more engaged and enthusiastic about

reading, they would choose to read more often in school and at home, and would therefore

complete a greater number of books than they had prior to the interventions.

The combination of Running Record and STAR data was used to determine whether

growth in student reading ability occurred throughout this research project. Student engagement

and enjoyment in reading was measured through their responses in the Student Survey as well as

with a count of the number of books read during the intervention period compared to books read

in a month prior to the intervention.

Accuracy of results. The researcher put a lot of consideration into the selection of tools

that would generate the data for this research project. The two standardized assessments being

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

19

utilized; running records and STAR Reading, are considered universal screening tools at her

school and are used with fidelity among many school districts and states. These credible

resources created an accurate picture of student growth in terms of reading ability. The student

survey of attitudes towards reading along with the number of books read pre- and postintervention are less universal tools, but equally important as they focus on each students beliefs

about reading and their desire to read. The combination of information from the four data sources

painted a clear picture of students reading ability and motivation to read before and after the

intervention process.

While the data collected is based on the results of one group of students, it is also a study

that can be replicated in other classrooms looking to measure the impact of implementing a

reading workshop model of instruction, utilizing the Building a Reading Life unit or other

reading workshop models. Transferability of the results of this research will be dependent on

both the sample selection being used as well as the use of the same data points and intervention

activities.

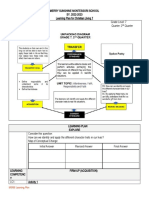

Table 1.

Data Collection Matrix

Research Questions

1. Preexisting

Knowledge

2. Reading Ability

3. Reading

engagement

1

Student Survey

Running Record Data

Student survey

Data Source

2

Running Record Data

3

STAR Reading

STAR Reading

Number of books

read.

Due to the triangulation of data points being used for the study (Table 1), the researcher

is confident that the results are dependable and accurate regarding the effectiveness of the

intervention and confirmed through the different sources of information. The two standardized

assessments are used in many situations to determine students level of performance in

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

20

independent reading tasks and are considered reliable data sources to impact instruction. While

less universal, the student survey will reveal relevant data about how students feel about reading

tasks and whether these feeling are altered as a result of the interventions. The collection of the

number of books read in the month before the intervention and the month of intervention is a

more objective representation of whether students increased their volume of reading throughout

the implementation of the reading workshop model. The same assessment tools are to be used

both before and after the intervention period, which means they can be compared in an accurate

and meaningful way to draw conclusions.

Data Analysis

The data collected from the aforementioned tools were kept anonymous and separate

from other student data. While the running record level and STAR assessment scores were

collected with individual students, the information about each students performance was in no

way connected to that student for the purposes of this study. The researcher wrote down the

individual scores from each of these assessments into a class chart and removed any identifying

information. In order to match pre-and post- intervention data, the researcher assigned each

student a random number that was associated with their running record and STAR assessment

scores.

Growth in these two areas was determined by individual and overall class growthfor

example, looking at the number of students who increased their reading level by one or more

letter levels or by averaging the grade-level equivalent scores for the class. The data from the

running record assessment is presented in a table that shows pre-intervention level, postintervention level, and how many levels of growth each student made. The STAR assessment

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

21

data is presented in two bar graphs, one showing individual student scores, the other comparing

the mean Grade-Level Equivalent scores for the class before and after the study.

The data collected about student motivation to read was collected anonymously and

therefore did not have any identifying information attached to it. The student survey was

conducted on the computer and did not collect student names or usernames. The number of

books read in a month was collected by the researcher and put into a table with students

identified only by a randomly assigned number. Another table shows the change in the number

of books read in a month.

As the data from the survey is less predictable than the straight-forward numerical data

collected from running records and the STAR assessment, the researcher broke the survey

questions down into more manageable pieces. Questions where students rated their feelings

about different types of reading were turned into tables showing the number of students who

selected each response. Information about how much time students spent reading outside of

school was presented in a bar graph to show change. Survey data showing the genres and types

of reading material students enjoy was put into a table representing the number of students who

selected each option.

Sample Selection

The sample selection for this action research consisted of nineteen fifth graders between

the ages of 10 and 11. The data collection and intervention strategies that make up this study

occurred within their regular reading instruction during the fall of 2015. Students entered this

fifth grade classroom with varied reading instruction experiences, reading abilities, and

motivation levels pertaining to reading.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

22

The students in this research project were the homeroom students of the researcher. The

researcher was their teacher for reading, writing, social studies, science, and word study

instruction on a daily basis. The sample selection was made as these students receive their

reading instruction from the researcher and were involved in the regular classroom instruction.

The only exception to this is Student 11, who received supplemental reading instruction for thirty

minutes a day due to an Individualized Education Plan. This child left the regular classroom

during the independent reading block of class to receive supplemental instruction and support in

reading.

The researcher who performed this study is a fifth grade teacher who has utilized several

literacy instructional practices over the five years she has been teaching at this school. In this

same span of time, the school has experienced massive changes including a new building, new

administrators, new math, writing, and word study curriculums, and increased access to

classroom technology such as one-to-one student laptops, no Interactive Whiteboards, and

HoverCam document cameras. The addition of technological resources has significantly altered

the teaching practices of the researcher who previously had use of an LCD projector (that was

shared amongst nine classroom teachers), a laptop for the teacher, and three desktop computers

within the classroom.

The school was planning to implement the Units of Study curriculum, a curriculum that

utilizes a focused reading workshop model, during the 2016-2017 school year. Prior to schoolwide implementation, administrators were looking for classroom teachers in each grade level to

pilot the program during the 2015-2016 school year. Pilot teachers were asked to utilize the

program and determine what resources and supports would be needed the following year when

the entire school would begin using it.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

23

The researcher involved in this study joined the pilot program in the hopes that utilizing

the curriculum would increase both student reading levels and student engagement in reading

activities. The researcher worked with five other fifth grade teachers over the course of the

school year to implement several of the Units of Study units, beginning with the Building a

Reading Life unit. This first unit is the initial framework of the program, and is intended to begin

the reading workshop instructional model in classrooms and build enthusiasm around reading.

Results

In teaching the twenty lessons found in the Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan,

2010) unit, the researcher implemented and developed a reading workshop model in her

classroom that emphasized student choice and accountability in reading. The data collection

methods utilized at the beginning of this five-week intervention period were conducted again

after the unit was taught with the hopes of seeing growth in student reading ability and

motivation to read. Students took the STAR reading assessment and were administered the

Teachers College Reading and Writing Project (2014) running records to determine their reading

performance level. Along with those two forms of data, the researcher administered a student

reading survey (Appendix A) with the intention of gauging students attitudes about reading.

Student motivation to read was also assessed through the collection of the number of books read

in the month before the unit was taught and the month during teaching to see whether students

were reading more as a result of this study.

Findings

Students were assessed using the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project (2014)

Running Record Assessment (Appendix A) approximately one month prior to the beginning of

the intervention. Students were reassessed using the same running record assessments

24

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

immediately following the intervention period. Table 2 shows the individual student scores from

both administrations of this assessment. Row 2 shows the level each student was reading at

before the intervention, while Row 3 shows the level each student was reading at after the

intervention. Row 4 shows the number of reading levels a student improved through the period

of this study.

Table 2.

Individual Running Record Levels

Student

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Pre-Intervention

Post-Intervention

Growth

The STAR Reading assessment (Renaissance Learning, 2015) was administered to the

students before and after the intervention period. Figure 1 shows the Grade Level Equivalent

scores for each student from the Pre- and Post- Intervention test. Figure 2 shows the class

average Grade Level Equivalent scores increasing from 6.5 to 6.8.

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

1

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Pre

Post

Figure 1. Individual Student STAR Grade Level Equivalents

25

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

7.1

7

6.9

6.8

6.7

6.6

6.5

6.4

6.3

Pre

Post

Figure 2. Class Average STAR Grade Level Equivalent.

Table 3 shows the number of books each student read in the month prior to the

implementation of a reading workshop instructional model and the month during which the

Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010) lessons were taught. Row 2 shows the number

of books read in the month prior to the intervention while Row 3 shows the number of books

read in the month the intervention was carried out. Figure 3 shows how the number of books

each student read in a one month period changed during this study.

Table 3.

Number of Books Read by Student

Student

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Pre-Intervention

11

Post-Intervention

10

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

26

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

-2

Figure 3. Change in the Number of Books Read by Student

The student survey (Appendix B) was completed by students before and after the reading

workshop model was implemented. This nine question survey looked at students attitudes about

reading. Question 1 of the survey asked students to describe how they think of reading, giving

them five options to choose from and allowing them to select as many options as they felt fit

their impression of reading. Table 4 shows the student responses to this question, each data point

represents one student who selected that response.

Table 4.

Number of Students Who Selected A Certain Attitudes Towards Reading.

Reading is

Pre-Intervention

Post-Intervention

Something I look forward to

10

One of my favorite things to do

Something I avoid

Something my teachers/parents

make me do

Something I do when theres

nothing else to do

Figure 4 shows the results of question 2 on the survey. This question asked students to

select the amount of time they spent reading at home on a daily basis. Students were given four

options to select from to represent the amount of time they spend reading. In this figure, the Yaxis represents the number of students who selected each option.

27

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Less than 30

minutes

30 minutes to 1

hour

Pre-Intervention

1-2 hours

More than 2

hours

Post-Intervention

Figure 4. Amount of time spent reading at home daily.

Table 5 shows the response to three questions regarding how students felt about different

types of reading; being read to by others, reading aloud, and reading to themselves. For each

question, students were given five options to choose from to best represent their attitudes

towards the type of reading described. The data in the table represents the number of students

who selected each option.

Table 5.

Number of Students Who Selected a Certain Attitude Towards Types of Reading

Which describes how you feel about being

read to?

Which describes how you feel about

reading aloud?

Which describes how you feel

about reading to yourself?

PrePostIntervention

Intervention

Pre-Intervention

Post-Intervention

Pre-Intervention

Post-Intervention

I hate it

I dislike it

Its ok

10

I like it

I love it

11

12

Table 6 shows students response when asked how likely they are to choose to read when

they have free time. Students were given five options to choose from to represent how likely they

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

28

are to choose reading as a free time activity. The numbers in the table represent the number of

students who selected each response option.

Table 6.

Number of Students Who Selected the Likelihood That They Would Choose to Read.

Pre-Intervention

Post-Intervention

I will definitely not read

I will probably not read

I might read

10

I will probably read

I will definitely read

Table 7 shows the response when students were asked about what genres of books they

enjoy reading. On this question, students were able to select as many options as they wanted to

or to add additional selections to demonstrate what types of books they like to read. The numbers

within this table show the number of students who selected each option.

Table 7.

Number of Students Who Selected Each Genre

Pre-Intervention

Post Intervention

Realistic Fiction

15

12

Fantasy

16

18

Mystery

10

10

Historical Fiction

Informational

Biography

Science Fiction

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

29

Table 8 shows the response when students were asked about what types of reading

material they like to read. On this question, students were able to select as many options as they

wanted or to select other and add additional selections to demonstrate what types of reading

material they enjoy reading. The numbers in the table represent the number of students who

selected each option.

Table 8.

Number of Students Who Selected Each Type of Reading Material

Pre-Intervention

Post Intervention

Chapter Books

16

15

Graphic Novels

Newspapers

Picture Books

Magazines

Ebooks

Other

Table 9 shows students responses when asked how they would describe reading.

Students were given a list of eight adjectives as well as a choice of other where they could fill

in their own descriptive words to describe reading. Students who selected other wrote in the

following responses: awesome, opens a new world, imagination, cool, strange, not my favorite

thing in the world, and it really depends on what Im reading. Students were able to select as

many options as they wanted to demonstrate their attitudes towards reading. The numbers in this

table represent how many students selected each adjective to describe reading.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

30

Table 9.

Words Students Use to Describe Reading

Pre-Intervention

11

Fun

8

Exciting

11

Interesting

3

Annoying

4

Easy

3

Boring

4

Important

0

Difficult

Awesome*

1

*4 students wrote it into the other

Post-Intervention

11

10

11

2

4

1

8

1

3

option

Discussion

Based on the data collected, the researcher feels that her original hypothesis regarding

student reading ability and motivation to read was accurate. The researcher believed that

implementing the reading workshop unit would lead to an increase of at least one reading level in

the four week intervention period. Table 2 clearly shows that each student increased their reading

ability by at least one level of the Teachers College Running Record (2015) assessment. Several

students increased their reading level by two or three levels, showing far greater growth than the

researcher had anticipated. Out of nineteen students, seven increased their reading ability by two

levels, four increased by three levels, two increased by four levels and one student increased her

reading by five levels. Prior to the intervention, nine of the nineteen students were at or above

the fifth grade expectation of a Level T. After the intervention, this number jumped to seventeen.

It is clear that working through the Building a Reading Life unit greatly improved students

reading fluency and comprehension, the two major components of the running record

assessment.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

31

The growth seen in the running record data (Table 2) is not consistent with the results of

the STAR reading assessment. The overall class average Grade Level Equivalent (GLE) score

increased from 6.54 to 7.02 (Figure 2). However, individual scores were more varied, and

several students showed a decreased GLE score (Figure 1). Out of nineteen students, eight

showed a decrease in their GLE score ranging from .1 to 1.1. This is significant as each tenth of a

point represents one month worth of expected growth. While the growth of other students offset

the average change in score enough to show overall growth, the lower scores found in 47 percent

of students in the study casts doubt on the amount of growth students made. Upon soliciting the

advice of her school literacy coach regarding the findings, the researcher discovered that there is

some doubt regarding the validity of the GLE scores from the STAR assessment. Therefore, the

researcher has determined, by looking at overall student growth on the STAR assessment and the

significant growth seen through running records, that students in the study did see an increase in

reading ability during the intervention period.

Growth in student motivation is clearly depicted through the data collected regarding the

number of books read by students. Table 3 shows that 18 of the 19 students read as many or

more books during the month of intervention than they had read in the month prior. The one

student who read one fewer book, is a student who reads voraciously and read several more

challenging books during the intervention period which the researcher believes slowed down her

number of books read, but helped her to increase her reading ability as her GLE score in the

STAR assessment increased by .8 and her running record level increased by one level. Figure 3

shows that thirteen of the nineteen students read more books during the intervention period than

they had previously read and six students read three or four more books than they had read

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

32

previously. This data clearly points to an increase in the amount of time students spent reading

which lead to an increase in their reading volume.

The student survey supports the claim that student reading increased through the

implementation of a reading workshop model. Figure 4 shows that students began reading for

longer periods of time. In the pre-intervention survey, nine students read less than 30 minutes a

day at home. In the post-intervention survey, that number was decreased to only two students.

Pre-intervention there were seven students reading for thirty minutes to an hour each day, while

afterwards that number doubled to fourteen. Pre-intervention, there were not any students who

reported reading more than two hours a day, post-intervention one student had increased his or

her reading volume to that amount.

Survey data also paints a clear picture of increased positive attitudes towards reading.

Table 4 shows students ranking their impressions of reading from most negative (Something I

avoid) to most positive (One of my favorite things to do). The option of Something I do when

there is nothing else to do was considered a neutral statement about reading for the purposes of

this study. Students were able to select as many of the statements they felt reflected their ideas

about reading. In the pre-intervention survey, five negative options were selected, ten positive

were selected, and eight neutral were selected. In the post-intervention survey, the number of

negative options selected was decreased to only three, the number of neutral statements about

reading also decreased to six. However, the number of positive statements selected was increased

to twelve. These numbers demonstrate an increase in positive associations with reading.

Student attitudes towards reading were further explored on the survey through three

questions that had students rank their feelings about different types of reading. Table 5 shows the

results when students were asked how they felt about being read to, reading aloud, and reading to

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

33

themselves. While there was some change in student attitudes, there was not significant enough

change to determine whether students attitudes towards types of reading activities became more

positive or negative. Overall, many students retained their original feelings about these specific

reading tasks.

Table 6 was more conclusive in looking at data regarding whether students would choose

to read in their spare time. Only one student changed their response that they definitely or

probably would not read, but the number of students who said they probably or definitely would

read increased from three to seven-demonstrating that more students were engaging in voluntary

reading than had in the past.

Tables 7 and 8 show data regarding the types of reading material and genres students

enjoyed reading. While there were no significant changes in the genres of books students liked,

the researcher did notice that the number of genres selected by students increased from 46 to 51

and that the number of types of reading material selected by students increased from 31 to 33.

While again not statistically significant, having fifth graders state that they enjoy a wider variety

of reading material or different genres is not to be taken lightly.

Table 9 shows students responses when asked how they would describe reading.

Students were given a list of eight adjectives as well as a choice of other where they could fill

in their own descriptive words to describe reading. Students who selected other wrote in the

following responses: awesome, opens a new world, imagination, cool, strange, not my favorite

thing in the world, and it really depends on what Im reading. Students were able to select as

many options as they wanted to demonstrate their attitudes towards reading. In this survey

question, the number of students who selected positive adjectives such as fun, exciting,

interesting and easy did not change much through the intervention process. However, three

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

34

students selected boring as descriptive of reading in the pre-intervention survey, while only

one selected it after the intervention. The number of students who identified reading as

important doubled from 4 to 8 though the intervention. This leads the researcher to believe that

some negative attitudes students had about reading, changed as a result of the reading workshop

model.

The data presented above supports the researchers initial hypothesis that introducing a

reading workshop instructional model, in particular the Building a Reading Life (Calkins and

Tolan, 2010) unit, would increase student reading ability and result in more students meeting the

fifth grade target of a Level T. Additionally, the researchers hypothesis that student motivation

to read would increase along with reading ability is supported by increased number of books read

by students and the attitudes portrayed in the student survey.

Limitations

During the data collection period, school was in sessions as scheduled and there were no

unexpected disruptions that impacted the reading instructional period. The researcher does see

that more time for each lesson would have allowed her to adhere more closely to the instructional

model found in the Building a Reading Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010) unit. Some lessons had to

be modified in order to fit into the 50 minute instructional block available. Additionally, the

researcher found that her students did not possess the stamina necessary to delve right into a 3040 minute independent reading block. Therefore, students were initially frustrated with the long

stretch of time they were being asked to read independently, and the researcher had to modify the

first four lessons of the unit in order to scaffold students reading stamina until they were ready

to utilize the entire time.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

35

One significant limitation of this study was the use of the STAR Reading Assessment

(Renaissance Learning, 2015) Grade Level Equivalent scores. Initially the researcher felt that

this data point would be useful in determine whether there was an increase in student reading

ability as a result of the intervention. After seeing the individual results of the STAR assessment

(Figure 1), the researcher was surprised to discover that several students scores went down

during the post-intervention administration of the assessment. The researcher learned afterwards

that the Grade Level Equivalent measurement is not deemed an accurate account of student

reading ability by the instructional coaches and curriculum administrators of her district.

Therefore, redevelopment of this study would utilize another form of data from the STAR

reading assessment such as the Scaled Score or Percent score.

Another area in which the researcher would recommend modifications to this study is in

the use of data about the number of books students completed. While this information was

important in helping the researcher determine that students increased their volume of reading,

further reflection determined that it was not as accurate of a measure as the number of pages read

would have been. Since books vary greatly in their length, a student who read one 350-page book

would have read more than another student who read three 100-page books.

Summary and Further Research

Based on the aforementioned results, the researcher is confident that student growth in

both reading ability and motivation to read occurred as a result of the implementation of a

reading workshop instructional model. All students showed growth in the level of texts they

could independently read with adequate fluency and comprehension. While not all students

showed growth in the STAR reading assessment Grade Level Equivalent scores, the overall class

average increased and many students did show growth. Just as important as an increase in

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

36

reading ability, students in the study demonstrated an increased motivation to read and more

positive attitudes towards reading through the number of books they read and their responses to

the student survey. These results, coupled with classroom observations that students were more

enthusiastic about the books that they were reading and reading instruction, make it clear that

student reading ability and motivation to read was increased by the use of the Building a Reading

Life (Calkins & Tolan, 2010) unit.

Further research into the implementation of a reading workshop model, specifically the

Units of Study curriculum will need to be completed before it can be determined whether the

curriculum increases both student reading ability and motivation to read. This study was limited

to one classroom of students utilizing one unit of the curriculum. This curriculum is designed for

students in kindergarten through fifth grade and consists of multiple units for each grade level.

Therefore utilizing this unit with another group of students will further support the validity of

these findings, however it will also be necessary to measure the impact of the different units

being used at each grade level. Other teachers participating in the pilot program for this

curriculum may or may not be able to support the results of this study. Similar data collection

tools will need to be used by all the teachers in the pilot program throughout the school year to

determine whether student growth is occurring. Regardless of the findings, the district plans to

implement this reading program for all students in kindergarten through fifth grade for the 20162017 school year.

Action Plan

Through this action research study, the researcher saw growth in both student reading

ability and motivation. Her first step is to share these results with her students. Seeing the

amount of growth will help students to see the effect of their hard work throughout the

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

37

intervention period and open up a dialogue about how their reading has changed since

implementing a reading workshop program. After discussing results with students, the researcher

plans on sharing the study with the rest of the reading pilot program. These teachers are all

involved in adopting the Units of Study (Calkins, 2015) curriculum. The school literacy coach is

also a part of this team, and is interested in the results of this study to help guide implementation

efforts for next school year when the entire school begins using this program. Another step in the

researchers action plan is to bring these findings to the school leadership team, so that it can be

used to encourage other teachers as they begin this reading program next school year.

Beyond sharing the results of this study, the researcher plans to use this information

going forward with this curriculum. The pilot program plans to implement two or three other

units from the curriculum this year. Knowing what worked well this first unit will influence the

researcher in starting the other units. After experiencing the first unit this school year, the

researcher knows what worked well with students and what supports will be needed going

forward with this program and to facilitate the second year of this curriculum.

Conclusion

This action research study demonstrated the effectiveness of implementing a reading

workshop teaching model on student reading ability and motivation to read. The researcher

observed considerable growth in the Teachers College Running Record level that her students

were reading at, as well as a more positive attitude towards reading. The researcher also found

the increase in the number of books read in a month significant, as it demonstrated a practical

application of reading skills and engagement in reading. The positive results revealed in this

study have created a positive outlook on the impending implementation of the Units of Study

curriculum (Calkins, 2015) that will occur during the 2016-2017 school year. The researcher

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

38

found that this program had positive results for students and would create a focused atmosphere

in which reading is a positive and engaging activity for student. Further research will need to be

done to see whether other groups of students see similar positive results and to determine

whether long-term learning objectives are met through this curriculum. The researcher is

adamant that she will utilize a reading workshop instructional model for teaching reading in the

future, as she sees the impact it has on students.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

39

References

Allington, R.L. (2012) What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-based

programs. (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Anderman, E.M. & Anderman, L.H. (2014). Classroom motivation (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Pearson.

Beers, K. (2003). When kids cant read: What teachers can do. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Calkins, L. (2015) Units of Study: A guide to the reading workshop: Intermediate grades.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Calkins, L. & Tolan, K. (2010). Building a reading life. Stamina, fluency, and engagement.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Meyer, K.E. (2010). A collaborative approach to reading workshop in the middle years. The

Reading Teacher, 63(6), 501-507.

Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer. Awakening the inner reader in every child. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, M. & Higgins, B. (2008). Beyond test preparation: Nurturing successful learners through

reading and writing workshops. Kappa Delta Pi Record. 44 (3) 124-127

Renaissance Learning (2015). STAR reading. Retrieved from:

https://www.renaissance.com/products/star-assessments/star-reading

Swift, K. (1993) Try reading workshop in your classroom. Reading Teacher. 46(5): 366-371.

Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. (2014). Running records, foundational

assessments and benchmarks. Retrieved from:

http://readingandwritingproject.org/resources/assessments/running-records

Towle, W. (2000). The art of the reading workshop. Educational Leadership. V.58: 38-41.

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Wolters, C.A., Denton, C.A, York, M.J., & Francis, D.J. (2014). Adolescents motivation for

reading: Group differences and relation to standardized achievement. Reading and

Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27(3): 503-533.

40

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Appendix A: Running Record Assessment

41

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

42

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

43

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

44

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

45

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

46

IMPACT OF READING WORKSHOP ON READING ABILITY AND MOTIVATION

Appendix B: Student Survey

47

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Application Form and Annexure-III Under NEP 2022-23Documento1 paginaApplication Form and Annexure-III Under NEP 2022-23Office ShantiniketanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Board of Intermediate Education, Karachi H.S.C. Part I Computer Science Practical Examination, 2017Documento8 pagineBoard of Intermediate Education, Karachi H.S.C. Part I Computer Science Practical Examination, 2017All Songs100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Psychologist Exam With AnswersDocumento13 paginePsychologist Exam With AnswersdrashishnairNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Questionnaire Checklist (Survey Copy)Documento2 pagineQuestionnaire Checklist (Survey Copy)ma.sharine valerie PablicoNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- WEEK 7 LT FinalDocumento1 paginaWEEK 7 LT FinalShiela Mae BesaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- People As Resource Class 9 Extra NotesDocumento5 paginePeople As Resource Class 9 Extra Notessidd23056% (9)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Sharmaine Joy B. Salvadico, Maem: Prepared byDocumento21 pagineSharmaine Joy B. Salvadico, Maem: Prepared byShareinne TeamkNessuna valutazione finora

- Graphic Design Thinking Beyond Brainstorming EbookDocumento4 pagineGraphic Design Thinking Beyond Brainstorming EbookSam NaeemNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- CL 2nd 2Documento6 pagineCL 2nd 2Teacher MikkaNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Limba Engleză. Asistenta Sociala.Documento59 pagineLimba Engleză. Asistenta Sociala.Radu NarcisaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Unit IV, HRD InterventionDocumento33 pagineUnit IV, HRD InterventionAnita SukhwalNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Stritchmed Spring Summer 08Documento16 pagineStritchmed Spring Summer 08John NinoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Komunikasyon Sa Akademikong FilipinoDocumento17 pagineKomunikasyon Sa Akademikong FilipinoCharo GironellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Training: 6 Edition Raymond A. NoeDocumento45 pagineStrategic Training: 6 Edition Raymond A. NoeHami YaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Human BiologyDocumento1.277 pagineHuman Biologyferal623Nessuna valutazione finora