Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Carbon Capture Fallacy 2015 PDF

Caricato da

Anonymous jSTkQVC27b0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

67 visualizzazioni7 pagineTitolo originale

Carbon Capture Fallacy 2015 copy.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

67 visualizzazioni7 pagineCarbon Capture Fallacy 2015 PDF

Caricato da

Anonymous jSTkQVC27bCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 7

msn

The Carbon ‘

He eee Omer accents yng

PT Oat MMM cer nu eceon El co hg

WA ea ao

evi i isseir

ceponer Sencar,

‘im Pinkston has built a massive

chemistry set in the middle of

a longleaf pine forest in eastern

Mississippi. “I’m so happy to see

it come to fruition,” says Pinkston,

arangy engineer with owlish

eyes, during a tour of the Kemper

County Energy Facility on a warm

summer morning.

‘Standing on lange expanse of flat land that has been clear

ccutand paved with conerete he Is pointing toa vast complex of

‘wvisting, turning pipes, hundreds of miles in all, that surges

skyward. At the enter ofthis cross between a chemical factory

and a power plant are two towering silos more than 900 feet

tall The twin gasiies, each weighing 2,580 tons, can create the

heat and pressure ofa voleano, That is what is required to take

lignite, a wet, brown coal mined from almost underneath Pink-

ston’ feet, and tur it nto gaseous foe that is ready to burn to

generate electricity

What makes this chemistry set extraordinary is not the fuel

it will soon produce but how It will handle the chief by-prod-

uct; carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas behind global warm-

‘ng. Rather than send the CO up a smokestack and into the at

iigsphere, as conventional coal-fired power plants do, Pinkston

‘and his colleagues at Kemper will eapture it

‘Kemper isthe most advanced coal plant in the US, And itis

key to a worldwide effort to cut back emissions of greenhouse

s1ses, a long-avalted goal embraced by most of the more than

190 nations holding climate negotiations this month in Pars.

Coal-ired power plants are the biggest source of the world’s

(00, discharges because the most polluting countries rely on

them to produce a large share oftheir electricity, Few of those.

nations, inchuding the US, which gets 40 pereent of its power

from coal, are willing to stop the burning. Without closing the

plants, the only way these countries can meet their pledges sto

keep CO, from going skyward, locking it away instead.

‘here 1s no credible plan to stave off global warming,

‘whether from individual countries or the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change, that does not include such eazbon

capture and storage, or CCS, technology. Even the scenarios

that rely heavily on nuclear power or renewable energy still re

‘quire carbon capture to clean up emissions from all the neces-

1 meine

Misilppi Power is bling the

Kamp “san coat” powerplant 0

eres elec fm the dest

Foe foal and apr theresling

carton dove enisons ited of

senng hem othe aes

Kempe wills ie, 0acopany

that wl ump down eo dis

ing ol fis t free out mare of

‘chy ofa ted ofthe CO emisons

ie pps wo romain appa urd

your here Binge ol. howe,

January 2016

ouldserd ne esis noth sy

(Goats a Kempe nae esi

lori very high ring dou

shout wbsher the appaad i x

arial sustirabl ode, 8 ca

bon capture and erage poets

teen dt down ores were.

‘Wahout efectve aflorsle carbon

capt sation ahs months Pas

climate ts tata commiting to

‘tension wl not beable to meet

theplooes.

Bac:

AL, at

sary cement and steel. There are more than 6,000 large, in

dustrial sources of CO, emissions in North America alone.

About 1,000 of them are cement kilns or factories that emit

100,000 tons or more of CO, # year. Nearly 5,000 of them are

power plants that burn fossil fuels, which emit even more,

‘Add thousands of fossil-fuel plants in China, India and else-

where, and they account for more than 70 percent ofthe plan

‘3 CO, pollution tis easy to see why C

ing this pollution

‘The trouble is that carbon eapture is an expensive fx. The

technology Itself seems to work, but the eos to build and oper

ate a full-scale plant, which is coming to light as Kemper nears

completion and other, smaller facilities gain experience, has

been very high. Then there is the question of what to do with

‘the carbon once it has been captured. Storing It deep under-

‘ground in geologic formations that could hold it for thousands

fof years adds even more to the cost. Governments are loath to

{oot the bil, To reeaver their investments, plant owners would

have to raise their customers’ electricity rates far above those

‘currently in place.

The cost of CCS has seuttled once promising efforts. A dem

onstration project at the Mountaineer coal plant in West Vie-

sinia buried more than one 1

s central to reduc

lion tons of COs, then shut

KEMPER HAS REQUIRED 172 miles of tangled pipes, 40,000 tone

of steet and two giant gasifiers (one at center, above right) to convert

dy coal into a cleaner-burning gas and to prevent the CO2 by-

product from being dumped into the atmosphere.

own for lack of funds to continue the experiment. In 2015 the

US. Department of Energy canceled its hallmark FutureGen

venture with industry, which was meant to rebuulld an old coal

plant in Mlinois, after spending $1.65 billion. China has quietly

changed the name of its flagship GreenGen CCS proje

Jar to Kemper~and is running the plant to produce power but

without capturing CO3. Only 15 CCS projects are operating

worldwide today, with another seven under construction, in

cluding Kemper. All have cost billions of dollars to study, de-

sign and complete.

Kemper has founda creative way to finance its project, how.

ever. It plans to pay for CCS by siphoning off the CO and selling

it, an approach known as carbon eapture and utilization. Some

‘companies might use CO, as an ingredient In baking soda, dry

‘yall, plastics or fuel, But emissions from power plants world

‘wide dwarf even the raw materials thet go into the more than

four billion tons of cement made every year, one ofthe largest

produets that might use the gas, “With the amount of CO, we

have to deal with, youre not going to tum everything nto a valu

able materia” says Ah-Hyung ‘Alissa Park a chemical engineer

‘at Columbia University, who works on this challenge.

There is one customer that could use lots of CO, and is

‘wealthy enough to pay fori: Big Ol. Petroleum companies need

vast amounts of C02, which they pump underground to force

‘outoil from wells that otherwise would be running dry. Carbon

capture and utilization presents a contradietion: Does it make

sense, as a response to climate change, to capture earbon only

touse itto obtain more fossil fuels for burning?

THE LABYRINTH

"HE KEMPER PRorEcT began back in 2006, in the aftermath of

Hurricane Katrina, which contributed to surge in natural gas

prices. Mississippi Power was headed toward a future in which

80 percent ofits cleetrcity would be generated from natural

‘58, according to spokesperson Lee Youngblood. Nuclear power

‘as too expensive, and renewable sources sich as wind and so:

lar were too intermittent, That left the local lignite. The adja.

cent countryside holds nearly 700 million tons ofthis dirtiest,

‘wettest kind of coal—more than enough for a power plant with

‘Kemaper’s capacity to burn for 50 years or more

Conventional coal power plants typleally avoid lignite be

‘cause cleaning the alr pollution itereates, much less the COy, is

daunting. Pinkston and his partners realized that designing 3

power plant around two towering gasifiers would alow them to

‘se the lignite and still keep pollution below federal limits. They

also realized that by adding more equipment they could capture

the COs, which mae strategie sense as plans were lai; Con-

ress was strongly considering legislation to cap greenhouse gas

Pollution. in 2009 the Magnolia State gave Mississippi Power

permission to bulld Kemper, witha cost limit of $2.88 billion,

Mississippi Power's parent corporation, Southern Company,

hhad already developed the gasifier ithe 1960s as part af exper

iments to turn lignite Into a cleaner fuel. Pinkston’ team chose

‘an industrial solvent, Selexl, to grab CO, from the gas created

by pressurizing and heating the ditty coal, Subsequently drop-

Ping the pressure would readily release the CO, from the so!

Carbon capture makes

for big, costly power

plants, much like

nuclear power. As

a result, the list of

dead projects is long.

vent, like twisting open the eap on a bottle of seltzer. The ap-

proach meant that less of the energy generated from the coal

hhad to be devoted to cleaning up the pollution, lowering the

‘ost, nd ft seemed like i all eould be done with various pieces

of technology that had been used in other ways for years.

“There's nothing new here but the integration,” says Bruce Har:

Fington, assistant plant manager for Kemper,

‘That integration has proved trickier than expected. The part

of the plant meant to dry the coal had tobe torn down and re-

built as a result of faulty parts. The labyrinth of pipes just kept

srowing as Kemper got but, stretching to 172 miles, 76 miles

‘more than planned. Workers inside the glant tangle painted

‘some of the machinery a special lu that turns colors if it gets

too hot or eold—one of the only ways to see inside the maze to

‘make sure everything is working properly, despite instruments at

‘more than 90,000 points. Engineers with petrochemical exper.

tise had to he imported, wd 2,300 miles of electrical cable had

«

fe

h

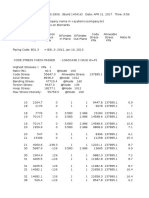

How IT WORKS

Carbon Capture

‘The Kemper power plant strings together

‘existing technologies in anew way.

Startwith nie, the dties kind of eo

Convert it nto gas (thats leaner to

bum (2) to create electric (3), leaving

behind carbon dloxide that ean realy

be captured instead of blowing up a

| smokestack inta the air Then use that

CO, 0 extract oll fom od unproductive

oil fle (4. Some of the CO, will

become locked underground (5), soit

does not reach the atmosphere and add

to global warming. A hand of planes

similar to Kemper have been bulk

‘worldwide, but they are proving tobe

‘@remely expensive; mary have been

shut down or canceled because of

| _cerstuation delays and cost overruns

Oogentomair

a

Brow cal ite)

(62 SeienticAmercun, January 2018

esr

ook the Coa

® ‘Heat the coel under high

meee arya

essehans

Caton capture

Cbonmonaie,

hygtogenandeabon

oe oa)

OO

Ah

os @ Clean the Gas

Prose yng to crate

ir cone

anderen mone ue

nds of OD

sation by a ge Mis

6A

LIBERTY BELLE: The 1,000-horsopower strip-ining machine

‘sparked onthe dirt expose after forest was clear-cut wating

todredge another trench to grab wet lignite coal hth

to be laid, leading to a doubling ofthe construction workforce.

All ofthis complexity inflated the cost: as of Oetober, Kem:

‘per was $3.9 billion over budget, up from $2.4 billion when the

Southern Company's flings to the US, Securities and Exchange

Commission, The company had to pay back hundreds of mile

lions of dollars in feel tox credits tld to project milestone

{acllty was proposed in 2009 to $6 billion. Mounting delays dates that were missed,

‘have pushed the start date from May 201410 atleast April 2016; ‘Mlssissippt Power has had to turn to its own customers to

every month of delay costs at least $25 mullion, according to avokd bankruptcy as it builds a power plant worth more than al

@ Extract on @, 8) Carbon Burial

mph COinerrndo ore a TheCO tesa depundegonunaly

‘eal from aldo fees, Some CO raid stored inthe tn spans between girs of and

‘9 trapped there reuse the CO, insandstove, here the oh prevostybeeneld, |

‘Hatreums forasubsequent ele

Caron done Twothidsof

Oyisrssed

One hrdaf Oy preied

‘oremainurdeground

B) Produce Power

7 Bumbo fea inturbines to generate

ect usa the ers esto make

start pins separate abies,

rong onal elect.

January 206, SesentieAmeriet.com 63

‘the rest of the company’s assets put together. In August it raised

clectricity rates by 18 percent. The big solution, however, is to

sell pre, dry CO, to the oil industry.

(OIL TO THE RESCUE

‘on conmaas have been. using CO, to seour more oil out ofthe

ground for decades, buying the gas from other companies that

fended up delling into underground deposits oft rather than the

oil or natural gas they sought, They build a kind of mint factory

atop an oilfield that compresses the CO, und pumps it down be-

To The CO, mixes with the oll to make it low easier an restores

the pressure underground to force more ofl to the surface. AS

‘much as two thirds of the CO, that gets puniped down returns

‘with the oil That CO, gets eomabined with fresh supplies and sent

‘back down to push up yet-more oll Fach cyele about one third of

the gas remains underground, caught in the tiny pres in sané

stone like te ol befor it Thats the climate benefit—burying the

treenkiouse gas away from the atmosphere.

‘The Tinsley oil ficld near Kemper has produced more than

220 million barrels of ol since its discovery in 1999. Such a bis

field ean warrant the big cost of buying CO, from # place like

Kemper, along with added roads, truck trips and CO, pipelines,

to foree out another 100 milion barrels. Denbury Resources be

‘gan flooding, the field with CO, from natural deposits in Mare

2008. At Tinsley, the company now recycles 670 million cubic

feet of CO, a year and buys an additional 100 million eubie feet

‘annualy, boosting oll production from the field from 50 barrels

‘a day to more than 6,000 barrels daily. When fully operational,

Kemper plans to send roughly 60,000 million cub feet of CO

year through a new 60-milelong pipeline to Tinsley and other

fields inthe region,

‘The eateh, of course, Is that when the extra oil is subse

‘quently burned as gasoline, home heating fuel or other petro

eum fuels, more 00, is sent into the atmosphere, The idea that

combating climate change depends on a technology that uses

CO; to produce more oil that lien gets burned, producing more

(C0,, reliably elicits chuckles from oil fetd workers.

Nationwide, the US. produces roughly 300,000 barrels of

ofl aday with COs, from nearly 140 fields, a number expected to

‘double if low oil prices rebound. ‘The DOE estimates there are

‘Pa milion barvel of olin the US, including Alaska) that could

be recovered every day with CO, Already 5,000 miles of pipe

Tine shuttle CO, from natural deposits such as the Jackson

‘Dome in Mississippi to old oll elds, like a spider's web lurking

just underground and occasionally breaking the surface with &

valve or pump.

PRICEY PROPOSITION

{TAPPING 003 in deposits currently costs about $0.50 per ton. Car-

bon dioxide from the complicated Kemper facility, however,

‘may cost wp to three times that.

CCost lessons are coming from several places, notably one of

the fst CCS projets, atthe Boundary Dam power plant in Sas

‘katchewan, In October 2014 the “clean coal" power plant began

feeding power into the electri grid. SaskPower spent a little

‘ore than $1 illion to rebuild one ofthe plants three coal-fired

boilers to capture its CO, emissions, The expense worked out to

bout $11,000 per kilowatt of electric generating capacity, mare

than three times as much asa typeal boiler, Mississippi Power's

SAUCE sO

estimate for Kemper is similar: at least $10,000 per kilowatt

At those levels, capturing CO, would add at east $0.08 per

kilowatt-our to the consumer price of eletrcity, according

[DOE estimates, That is a 5 percent increase to the average

‘American price of electriity: $0.12 per kilowatt-hout. Without

regulations requiring carbon captare or a tax on earbon pollu

tion that power utilities would want to avoid, the companies

have litle financial reason to pursue the technology. The eco

hhomics are no better in China, whieh now consumes roughly

four times as mich coal as the US., or in India, whieh has de-

clared in its submission to the Paris climate taks thatt intends

tobuid many more coal-fired power plants. The new plants are

‘unlikely to have OCS because of the eost

-Bven ifthe expense of carbon capture comes down, the cost

‘of storage may also remain too high. Many ofthe more than 600

coal-fired power plants in the US. are nowhere near geologic

formations that might reliably hold CO that is simply pumped

‘underground for permanent storage. Many ofthe power plants

are also nowhere near the 1,600 US. ol eds that might benefit

from CO» injection, requiting long, expensive pipelines and

compressing stations. And selentsts cannot say with certainty

how much of a climate benefit using CO, to produce ofl would

offer. “We don't know the net amount of CO, stored,” says Ca

nlle Petit, a chemical engincer at Imperial College London.

RECKONING DEFERRED

‘As eases stows, carbon capture makes for big, expensive pow.

tr plants, much like nuclear power. As a result, the lst of de

funet projects such as FutureGen is long. Worldwide, 33 CCS

‘projects have been serapped since 2010, according tothe Glob-

‘al Carbon Capture and Storage Institute. Most consumed hun:

‘dreds of millions of dollars before failing. Taose that still exist,

such as Sunni Powers Texas Clean Energy Project, are strug

fling. Boundary Dam is having trouble meeting its own carbon

capture targets.

"Nevertheless, CCS projects continue because of the compe

ling need to combat climate change. NRG Carbon 360 is build

ing one in Texas called Petra Nova. The utility plans to make

money from selling eletecity and the of obtained by pumping

1.6 million tons of CO, a year into the West Ranch Oil Field near

Houston, Petra Nova, scheduled to come online in late 2016 at

the earliest, vill capture CO, from only 10 percent of the power

plant’ total eapacity however, at a cost of $1 billion.

“Cleaning wp coal plant emissions is a good goa,” says Al Ar

mendariz, a Sierra Club activist and former Environmental Pro

‘wetion Agency official. “But the costs ofthe Petra Nova project

especially compared with the low costs of renewables in Texas

like wind and solar, make it questionable if CS is the most ef

fective way to reduce carbon emissions

‘Therein lies the fallacy, Unless the US. starts to shut down

‘more coal power plants and even natural gas power plants, it

‘must find a way to convert CCS from an expensive luxury to &

viable fix, Otherwise the eountry will not meet its long-term

target of 80 percent cuts in greenhouse gas pollution by 2060.

‘Kemper does not provide much hope that carbon capture

canbe a cheap and easy solution, Two bulging stockpiles of dark

coal rse beside the behemoth, aking under the Mississippt sun,

‘waiting forthe gasifiers to start up. The nine-million-pound,al-

clectri strip-mine machine that dug it up, renamed the Liberty

ee

iE:

ia er

CAPTURING Kempers COs and other pollution requires the extensive |

labyrinth of ductsand towers shown above. The tall gasfiers that

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- KMC PDFDocumento5 pagineKMC PDFAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- OijadinDocumento29 pagineOijadinbbot909Nessuna valutazione finora

- WTO and Global Food SecurityDocumento5 pagineWTO and Global Food SecurityAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Finite Element Method: January 12, 2004Documento26 pagineFinite Element Method: January 12, 2004happyshamu100% (1)

- Assignment9 - Intro To Geography UCONN Fall 2016Documento1 paginaAssignment9 - Intro To Geography UCONN Fall 2016Anonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- OPE Displacement Urea Solution LineDocumento80 pagineOPE Displacement Urea Solution LineAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Concrete Mix DesignDocumento11 pagineConcrete Mix DesignAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- 14th Finance CommissionDocumento5 pagine14th Finance CommissionSarfaraj KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Protein-Misfolding Diseases - 2002Documento2 pagineProtein-Misfolding Diseases - 2002isaacfg1Nessuna valutazione finora

- I Need A Book: This Is The Free MethodDocumento2 pagineI Need A Book: This Is The Free MethodAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- MathDocumento1 paginaMathAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Carbon Capture Fallacy 2015 PDFDocumento7 pagineCarbon Capture Fallacy 2015 PDFAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes Pp1 26Documento26 pagineNotes Pp1 26Anonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- 017 InstDocumento5 pagine017 InstAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- NEXUS-5000 Series - NEXUS 5548UP Proposed As Core Switch-2 Nos. Without Expansion Module + Nexus 2K As Top of RACK SwitchDocumento29 pagineNEXUS-5000 Series - NEXUS 5548UP Proposed As Core Switch-2 Nos. Without Expansion Module + Nexus 2K As Top of RACK SwitchAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- 19-22 Apr On Semiconductor ShuteshDocumento1 pagina19-22 Apr On Semiconductor ShuteshAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- B E Regulation of Admission and Payment of Fees GSFC University FINALDocumento14 pagineB E Regulation of Admission and Payment of Fees GSFC University FINALAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipal MarchDocumento19 pagineMunicipal MarchJuanitoPerezNessuna valutazione finora

- SfdsdsDocumento1 paginaSfdsdsAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- Edit Registration Form - FDocumento1 paginaEdit Registration Form - FAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- GOES Global Online Enrollment SystemDocumento1 paginaGOES Global Online Enrollment SystemAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- E740199 KXPA100 Owner's Manual Rev A5Documento55 pagineE740199 KXPA100 Owner's Manual Rev A5Anonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- FrenchDocumento1 paginaFrenchAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- 56456474Documento1 pagina56456474Anonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- BVCVBCBDocumento1 paginaBVCVBCBAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- VCBCDocumento1 paginaVCBCAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- JHGHJDocumento1 paginaJHGHJAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- One Thing You Will Stumble Across Time After Time Is Gann S Master TIME Factor, It S in His Master Courses But It S Not Clearly Labeled For YouDocumento1 paginaOne Thing You Will Stumble Across Time After Time Is Gann S Master TIME Factor, It S in His Master Courses But It S Not Clearly Labeled For YouAnonymous jSTkQVC27bNessuna valutazione finora

- GHDGDDocumento1 paginaGHDGDAnonymous jSTkQVC27b100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)