Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Wildlife Lab-Large Brown Bats Stockton University: Alex Epifano, Aysia Gandy

Caricato da

api-301790589Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Wildlife Lab-Large Brown Bats Stockton University: Alex Epifano, Aysia Gandy

Caricato da

api-301790589Copyright:

Formati disponibili

WILDLIFE LABLARGE BROWN

BATS STOCKTON

UNIVERSITY

Alex Epifano, Aysia Gandy

Environmental Issues Fall 2015

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

I. Introduction

Large brown bats were

studied on Stockton University

campus in the Pine Barrens. A man

made habitat for bats to hibernate in

the winter and live in for the

summer was built in order to restore

the dwindling bat population. The

bats need habitat Bat boxes are

constructed because in suburban

areas bats are living in the attics of

peoples homes and trees are

getting cut down where some of the

bats are living. The majority of

ecological and behavioral research

on

temperate insectivorous bats is from

species roosting in human

structures, because it is easier to

find and success bats roosting man

structure than in a natural site such

as

a tree cavity (Brigham R, Mark, Kalcounis C, Matina, 1998). So if made right, a bat box is easier for a

bat to access than a tree cavity that is hard to find. The bats are also declining in population because of

disease.

II. Methods

Scientific research was a big part of this experiment. Using the video camera looking in the old

bat box on campus right next to Lake Pam, there were no large brown bats in the bat habitat that the class

made from the year previous. It was a perfect time to check the box because bats sleep during the day and

come out at night. It looked like there was no damage like chips in the wood or fallen off pieces. Also,

there was no guano (bat droppings) so that seems that there was not even bats previous to our arrival.

Deciding the layout of the bat box, try to make the bat box a little bigger that the class before because

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

maybe the colony of bats around campus is big and do not fit into the box on campus. Getting exterior

plywood, screws, and staples we put together the bat box. Painted the box black two coats and painted

one clear coat so it last longer in the elements.

III. Discussion/Results

Bat populations are declining world-wide as a result of a growing number of factors, including

habitat loss and fragmentation, disturbances to roosts, exposure to toxins, human hunting pressures and

introduced predators (Agosta, 2002). Eptesicus fuscus also known as big brown bats are usually found in

the United States, Canada, South America, Central America, as well as some islands living in a range of

different habitats from deserts, meadows, to forests, mountains, cities, and chaparral. Humans around the

world and are constantly tearing down or

changing land structure to build houses, roads,

and farms creating a different construction of

land that the bats are not used to. When bats

roost they usually pick a location that is manmade and are high up such as ceilings of

buildings or caves not typically depending on

any species in order to live or create a habitat

for them. When buildings are torn down

because of abandonment or to be reconstructed

it usually leads to loss of their habitat. Roads are placed all over the world in order to make traveling

easier but it hasnt made life easier on species especially bats. It has been discovered that road ecology

has quantified impacts such as direct mortality due to vehicle collisions, the prevention of physical

movement and gene flow across landscapes, and decreases in the use of otherwise suitable habitat

(Kitzes & Merendlender, 2014) . Also as a result of farming and the distribution of pesticide on the land,

bats will have to relocate because the bugs that they eat are dying in those locations.

Big brown bats are insectivorous meaning they like to eat bugs, especially beetles. Bugs are so

abundant all over the world making it easy for them to find food in any of the wide variety of habitat they

are found. In New Jersey there are colonies of up to 200 individuals that return each spring to thousands

of homes and other buildings. They are also not endangered or threatened but there are some concerns for

their health when it comes to White Nose Syndrome. They are protected under the NJ Endangered and

Nongame Species Conservation Act as special concern. This disease is transmitted either directly

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

through bat-to-bat contact or indirectly through

contact with pathogen propagules in the environment

(Zukal et al., 2014). The hibernation patterns of bats

seem to play the largest role when it comes to the bats

getting infected. This disease attacks the bats when

their immune systems are at

their lowest causing the

disease to get into their

systems easily. The location

of where the bats hibernate

has been linked to the disease

as well, most of the

mortality has been

documented in species that

use underground hibernation

sites (i.e., caves and mines)

(Fenton, 2012). When the

bats skin is damaged by the

disease it results in

disruption of torpor pattern,

premature depletion of fat

reserves and mortality in

affected bats in North

America (Warnecke L,

Turner JM, Bollinger TK,

Lorch JM, Misra V, et al.,

2012).

A bat box on campus

should be on a pole that is at

least 10ft high, close to water,

and that is facing southwest

(Coll, Mike., March 2014).

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

Also, the box should have

at least 6-10 hours of sun

exposure because in July in

Galloway the average

temperature is 85 degrees

(Bat Conservancy

International). Where we

picked the bat box gets at

least 6 hours of sun

exposure. Putting the new

bat box close to the old bat

box is a good idea because

recent evidence suggests

that bat colonies using tree

cavities are not restricted to

individual trees. Instead,

colonies may be spread

among multiple trees on a

given night, forming

fissionfusion societies

(Brigham R, Mark, Willis,

Craig. September 2004).

This means the closer the better with bat boxes because the bats are not territorial. So this bat box will be

close to the old bat box but will be facing more south than previous bat box.

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

Appendix

WILD LIFE LAB- LARGE BROWN BATS

Bibliography

AGOSTA, S. J. (2002). Habitat use, diet and roost selection by the Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus

fuscus ) in North America: a case for conserving an abundant species. Mammal Review, 32(3), 179-198.

doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.2002.00103.x

Bat Conservation International. http://www.batcon.org/

Brigham R, Mark, Willis, Craig. ( September 2004). Roost switching, roost sharing and social

cohesion: forest-dwelling big brown bats, Eptesicus fuscus, conform to the fissionfusion model. Animal

Behaviour. Volume 68, Issue 3. Pages 495505.

Brigham R, Mark, Kalcounis C, Matina. (April, 1998). Secondary Use of Aspen Cavities by TreeRoosting Big Brown Bats. The Journal of Wildlife Management. Vol. 62, No. 2. Pp. 603-611.

Coll, Mike. (March 2014). Hildacy Farm Preserve: Nest box work. https://natlands.org/tag/mikecoll/

Fenton, M. B. (2012). Bats and white-nose syndrome. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of

Sciences Of The United States Of America, 109(18), 6794-6795. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204793109

Justin Kitzes, Adina Merenlender PLoS One. 2014; 9(5): e96341. Published online 2014 May

13.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096341

Warnecke L, Turner JM, Bollinger TK, Lorch JM, Misra V, et al. (2012) Inoculation of bats with

European Geomyces destructans supports the novel pathogen hypothesis for the origin of white-nose

syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 69997003.

Yohan Charbonnier, Luc Barbaro, Amandine Theillout, Herv Jactel PLoS One. 2014; 9(10):

e109488. Published online 2014 October 6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109488

Zukal, J., Bandouchova, H., Bartonicka, T., Berkova, H., Brack, V., Brichta, J., & ... Pikula, J.

(2014). White-Nose Syndrome Fungus: A Generalist Pathogen of Hibernating Bats. Plos ONE, 9(5), 1-10.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097224

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Seychelles Wildlife Colouring BookDocumento40 pagineSeychelles Wildlife Colouring Bookapi-348135772100% (1)

- The 100 World's Worst Alien Invasive SpeciesDocumento11 pagineThe 100 World's Worst Alien Invasive SpeciesCaetano SordiNessuna valutazione finora

- DEP 80.80.00.15 EPE - Guidance For Selection of SCEsDocumento88 pagineDEP 80.80.00.15 EPE - Guidance For Selection of SCEseankibo100% (5)

- A Manual of Forensic Entomology by Kenneth G.V. SMITHDocumento12 pagineA Manual of Forensic Entomology by Kenneth G.V. SMITHLic Carlos Nando SosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Garispanduan 1-97 EnglishDocumento15 pagineGarispanduan 1-97 EnglishCyrus HongNessuna valutazione finora

- BioDocumento178 pagineBiochevy94Nessuna valutazione finora

- Little Brown Bat-Final ReportDocumento17 pagineLittle Brown Bat-Final Reportapi-482524077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Definition Assignment English363Documento8 pagineDefinition Assignment English363api-644129074Nessuna valutazione finora

- Envl Issues Lab 3 - Habitat LabDocumento13 pagineEnvl Issues Lab 3 - Habitat Labapi-532122105Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aadcockpaper OneDocumento8 pagineAadcockpaper Oneapi-333272072Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cane Toad EssayDocumento4 pagineCane Toad EssayNickNessuna valutazione finora

- Conservation Ecology of Cave BatsDocumento38 pagineConservation Ecology of Cave BatsAlexandru StefanNessuna valutazione finora

- Keystone SpeciesDocumento12 pagineKeystone SpeciesFirda RachmaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Literary ReviewDocumento5 pagineLiterary Reviewapi-549216833Nessuna valutazione finora

- 100 of The World'S Worst Invasive Alien SpeciesDocumento11 pagine100 of The World'S Worst Invasive Alien SpeciesManikandan VijayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Should We Bring Back Extinct AnimalsDocumento2 pagineShould We Bring Back Extinct Animalsapi-391314886Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biodiversity and Healthy SocietyDocumento2 pagineBiodiversity and Healthy SocietyYumi koshaNessuna valutazione finora

- CorridorsDocumento7 pagineCorridorsapi-323831182Nessuna valutazione finora

- OspreyDocumento9 pagineOspreyapi-271025141Nessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Biodiversity: Biodiversity in Cities & TownsDocumento4 pagineUrban Biodiversity: Biodiversity in Cities & TownsFatema BhinderwalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Life History and Ecology of the Five-Lined Skink, Eumeces fasciatusDa EverandLife History and Ecology of the Five-Lined Skink, Eumeces fasciatusNessuna valutazione finora

- Should We Try To Bring Extinct Species Back To Life? ADocumento8 pagineShould We Try To Bring Extinct Species Back To Life? ANgọc TrâmNessuna valutazione finora

- Importance of Wildlife ConservationDocumento5 pagineImportance of Wildlife ConservationJay Elle Leewas75% (12)

- Biological Conservation: Christopher E. Cattau, Julien Martin, Wiley M. KitchensDocumento8 pagineBiological Conservation: Christopher E. Cattau, Julien Martin, Wiley M. KitchensMax RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Keystone Species: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocumento16 pagineKeystone Species: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchvvNessuna valutazione finora

- The Adverse Effects of Artificially Introduced Species: BackgroundDocumento13 pagineThe Adverse Effects of Artificially Introduced Species: Backgroundapi-357916215Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mary Bunch SC Department of Natural ResourcesDocumento22 pagineMary Bunch SC Department of Natural ResourcesskeeterhawkNessuna valutazione finora

- Eat Your Heart Out: Choice and Handling of Novel Toxic Prey by Predatory Water RatsDocumento5 pagineEat Your Heart Out: Choice and Handling of Novel Toxic Prey by Predatory Water RatsRudson RomeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Wildt, 1997Documento11 pagineWildt, 1997Adauto AlvesNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolution Work Sheet - AnsweredDocumento3 pagineEvolution Work Sheet - AnsweredJohn OsborneNessuna valutazione finora

- Independent Study PaperDocumento17 pagineIndependent Study Paperapi-432383831Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research EssayDocumento12 pagineResearch Essayapi-549216833Nessuna valutazione finora

- Browne y Hecnar (2007)Documento9 pagineBrowne y Hecnar (2007)Marita AndreaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary Practice Official 2017 SampleDocumento1 paginaSummary Practice Official 2017 Sampletuantu_51Nessuna valutazione finora

- 121 1995 Biodiversity at Its UtmostDocumento14 pagine121 1995 Biodiversity at Its UtmostArghya PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 Aquatic Insects Why It Is Important To Deicated Our Time On Their StudyDocumento9 pagineChapter 1 Aquatic Insects Why It Is Important To Deicated Our Time On Their StudyIvan GonzalezNessuna valutazione finora

- Genome Resource BanksDocumento20 pagineGenome Resource BanksFernanda GouveaNessuna valutazione finora

- Z00797-1 EditedDocumento21 pagineZ00797-1 EditedReginah KaranjaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eat Your Heart Out - Choice and Handling of Novel Toxic Prey by Predatory Water RatsDocumento6 pagineEat Your Heart Out - Choice and Handling of Novel Toxic Prey by Predatory Water RatsJean Carlos MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Final CM km-2Documento11 pagineFinal CM km-2api-283879098Nessuna valutazione finora

- Meandrina - Meandrites - Maze CoralDocumento5 pagineMeandrina - Meandrites - Maze CoralDavid Higuita RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- (English) Ryan Phelan - The Intended Consequences of Helping Nature Thrive - TED (DownSub - Com)Documento12 pagine(English) Ryan Phelan - The Intended Consequences of Helping Nature Thrive - TED (DownSub - Com)Maulana Yazid Al AnnuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Sibonius Is A Diurnal, Actively Foraging Snake Inhabiting TheDocumento2 pagineSibonius Is A Diurnal, Actively Foraging Snake Inhabiting Thelaspiur22blues7327Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is A Keystone Species WSDocumento3 pagineWhat Is A Keystone Species WSHusam AlSaifNessuna valutazione finora

- Sixth Mass Genesis: The Rise and Fall of SpeciesDocumento4 pagineSixth Mass Genesis: The Rise and Fall of SpeciesAZALEA MAE MANIMOGNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecological Importance of Birds - M A Tabur 2010Documento6 pagineEcological Importance of Birds - M A Tabur 2010crew90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Graciana B. Fuentes DDM 2-ADocumento4 pagineGraciana B. Fuentes DDM 2-AGraciana FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Structure and Abundance of Small Rodents at The Wave Front of Agroforestry and Forest in Alto Beni, Bolivia - 2020Documento10 pagineCommunity Structure and Abundance of Small Rodents at The Wave Front of Agroforestry and Forest in Alto Beni, Bolivia - 2020Abel Tome CaetanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 4 NotesDocumento13 pagineTopic 4 Notesapi-293573854Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tmp875e TMPDocumento11 pagineTmp875e TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Biodiversity and ConservationDocumento22 pagineBiodiversity and ConservationAwesome WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulletin: Bats of The Bahamas: Natural History and ConservationDocumento53 pagineBulletin: Bats of The Bahamas: Natural History and ConservationKelly SpeerNessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity, Conservation Status and Habitat Preference of Bats Found in Select Area in Paragua Forest Reserve, Dinagat Islands, PhilippinesDocumento19 pagineDiversity, Conservation Status and Habitat Preference of Bats Found in Select Area in Paragua Forest Reserve, Dinagat Islands, Philippinesrexter perochoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Journey into Adaptation with Max Axiom, Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceDa EverandA Journey into Adaptation with Max Axiom, Super Scientist: 4D An Augmented Reading Science ExperienceNessuna valutazione finora

- Bio 12 4th Exam TranscriptDocumento7 pagineBio 12 4th Exam TranscriptJonathan ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4: Characteristics in Ecosystems: Pages 84-131 NelsonDocumento79 pagineChapter 4: Characteristics in Ecosystems: Pages 84-131 NelsonFirdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Annual Reviews Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and SystematicsDocumento22 pagineAnnual Reviews Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and SystematicsMATHIXNessuna valutazione finora

- Adapative Species Management Plan KoalaDocumento14 pagineAdapative Species Management Plan KoalaChris LiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Conservation BiologyDocumento20 pagineConservation Biologyapi-267781539Nessuna valutazione finora

- Biology HSC Blueprint of Life NotesDocumento37 pagineBiology HSC Blueprint of Life Notescody jamesNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitt Et Al. 2003 - (History and The Global Ecology of Squamate Reptiles)Documento17 pagineVitt Et Al. 2003 - (History and The Global Ecology of Squamate Reptiles)Raissa SiqueiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 IntroductionDocumento37 pagineChapter 1 IntroductionManuel RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper On WolvesDocumento8 pagineResearch Paper On Wolvesafeawfxlb100% (1)

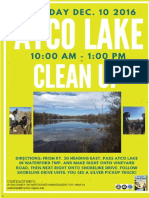

- Atco Lake Partnership ProjectDocumento5 pagineAtco Lake Partnership Projectapi-301790589Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rain Barrel WorkshopDocumento4 pagineRain Barrel Workshopapi-301790589Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aysia Gandy ResumeDocumento1 paginaAysia Gandy Resumeapi-301790589Nessuna valutazione finora

- Air PollutionDocumento10 pagineAir Pollutionapi-301790589Nessuna valutazione finora

- Watershed Management PlanDocumento16 pagineWatershed Management Planapi-301790589Nessuna valutazione finora

- UAE National Framework Statement For Sustainable Fisheries (2019-2030) EnglishDocumento25 pagineUAE National Framework Statement For Sustainable Fisheries (2019-2030) EnglishHawra SafriNessuna valutazione finora

- Development and Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento11 pagineDevelopment and Sustainable DevelopmentDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (1)

- Tiger Fact Sheet FINALDocumento2 pagineTiger Fact Sheet FINALVijay PatilNessuna valutazione finora

- AJAD 2005 2 1 2 6brionesDocumento13 pagineAJAD 2005 2 1 2 6brionesHaruki AkemiNessuna valutazione finora

- Earth Science (Fresh Water Reservoir)Documento13 pagineEarth Science (Fresh Water Reservoir)FedNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecosystem Unit Performance TaskDocumento1 paginaEcosystem Unit Performance Taskapi-485795043Nessuna valutazione finora

- Monitoring Stream Channels and Riparian Vegetation - Multiple IndicatorsDocumento57 pagineMonitoring Stream Channels and Riparian Vegetation - Multiple IndicatorsHoracio PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eutrophic DiagramDocumento1 paginaEutrophic DiagramMr. BrewerNessuna valutazione finora

- PreviewpdfDocumento58 paginePreviewpdfJoseph SofayoNessuna valutazione finora

- ARC1041H Project 1 Brief 2019 - SmallDocumento4 pagineARC1041H Project 1 Brief 2019 - Smalljs htNessuna valutazione finora

- The Conversion of Agricultural Land Into Built SurfacesDocumento6 pagineThe Conversion of Agricultural Land Into Built Surfacesstoica_ramona_5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Citizen Science EOI Final SMLDocumento2 pagineCitizen Science EOI Final SMLHealthy Land and WaterNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Land Management PracticesDocumento48 pagineAssessment of Land Management PracticesSaid AbdelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dynamics of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change in Tropical RegionsDocumento41 pagineDynamics of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change in Tropical RegionsPoppy CassandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecology: Unit 1: The Study of Life A. TreacyDocumento5 pagineEcology: Unit 1: The Study of Life A. TreacyM ANessuna valutazione finora

- Semirata Bidang Ilmu Pertanian BKS PTN B 2011-Sarno Et Al UnsriDocumento5 pagineSemirata Bidang Ilmu Pertanian BKS PTN B 2011-Sarno Et Al UnsriAgus RinalNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018 RecipientsDocumento5 pagine2018 RecipientsGurusuNessuna valutazione finora

- IsotopesDocumento5 pagineIsotopesAhsan HomarNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 PlanDocumento7 pagine2022 PlanSK Alma VillaNessuna valutazione finora

- River Rehabilitation: Preference Factors and Public Participation ImplicationsDocumento23 pagineRiver Rehabilitation: Preference Factors and Public Participation Implicationsbunga djasmin ramadhantyNessuna valutazione finora

- USAID Procolombia Guides-Handbook v2Documento301 pagineUSAID Procolombia Guides-Handbook v2Nz rineNessuna valutazione finora

- Indias Notified Ecologically Sensitive AreasDocumento112 pagineIndias Notified Ecologically Sensitive AreasVidya AdsuleNessuna valutazione finora

- Our Environment Nowadays SpeechDocumento2 pagineOur Environment Nowadays Speechfarylle gaguaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Concept of The EcosystemDocumento26 pagineThe Concept of The EcosystemVinoth Kumar Kaliyamoorthy100% (1)

- WS - Changing - Climate - Changing - Environment - U3 (Answer)Documento2 pagineWS - Changing - Climate - Changing - Environment - U3 (Answer)Gladys IpNessuna valutazione finora

- Threats To BiodiversityDocumento4 pagineThreats To BiodiversityDanna AguirreNessuna valutazione finora