Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Plagiarism Discourse

Caricato da

api-275162743Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Plagiarism Discourse

Caricato da

api-275162743Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Running Head: PLAGIARISM DISCOURSE AND LANGUAGE LEARNERS

Plagiarism discourse and English language learners

Angela Sharpe

Colorado State University

Plagiarism discourse

Introduction

There are many ways in which writers insert their judgments, values, opinions, and

knowledge into their writing. One of the devices for gaining credibility with their audience

while taking a stance in writing is through citing and paraphrasing other research. As novice

members of an adopted discourse community, English language learners are confronted with the

temptation to copy others words due to: 1) a lack of confidence in their own language ability,

especially their phraseology in academic discourse; 2) English language learners may place more

trust in something that has been written and reviewed by others than their own writing; and 3)

the electronic age makes the temptation to copy and paste from various sources very enticing as

the task of writing a research paper using their own language can be very overwhelming. This

paper will highlight some of the unintentional instances of plagiarism by second language writers

in order to illustrate a continuum of plagiaristic behavior and intention in order to contrast the

current state of dichotomizing students as either unethical plagiarizers or honest writers with

integrity.

Through published and reviewed research, writers attempt to base their ideas in

previously grounded research. Likewise, based upon a review of literature, primarily in applied

linguistics and TESOL, this research review focuses on plagiarism as a concept as well as its

many forms with regard to second language writing. A short review of the historical roots of the

concept of plagiarism, along with some terminology employed in discourse about plagiarism will

be used to examine the complexity of the issue. This paper will utilize texts used at an intensive

academic English program to teach learners about plagiarism and citation conventions as a basis

for primary source examples on plagiarism discourse. The following anecdotal comment,

included on an ELL writers manuscript, summarizes the issue that many second language

teachers are familiar with: your work is both good and original. Unfortunately, the parts which

are good are not original, and the parts which are original are not good. (as cited in Pecorari

2003, p. 318). Although, the comment is rather harsh it does illustrate a dichotomy

representative of the matter.

The historical roots of plagiarism

In order to understand how plagiarism is conceived in todays academic environment, it is

relevant to review its historical roots. Pennycook (1996, p. 5) posits that in order to understand

current conceptualizations of plagiarism we must first examine how author, authenticity, and

authority are understood and intertwined in Western thought. In premodern times (e.g.biblical,

medieval), imagination was thought of largely as a reproductive process rather than a productive

process, that is, the images in our minds were thought of as reproductions of reality or imitations

of an original. During this time, it was believed that the production of any text came from a

divine source channeled through a human medium. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the

Enlightenment, also called the Age of Reason, caused a great shift in thinking in Europe.

Plagiarism discourse

Imagination became thought of as a productive activity and textual meaning was attributed to the

human mind instead of divine origins. This shift put emphasis on the human mind as the center

of creativity and idea formation, however, during this time the notion of property rights on ideas

produced discourse on ownership of ideas and language. Flowerdew and Li (2007, p.162) show

how plagiarism, or an overwhelming concern for authorial rights, is an Anglo-Saxon concept

which can be traced partly back to the invention and rise of the printing press during the 15th and

16th centuries coupled with the origin of copyright law in England and the United States during

the 17th and 18th centuries. Swales and Feak (2004, p. 172) define plagiarism as a deliberate

activityas the conscious copying from the work of others. They point out that plagiarism has

become an integral part of Western academic thinking and the assumptions that it is based upon

may not be shared by all cultures. Similar to Flowerdew and Li (2007), Swales and Feak (2004,

p.172) show that their definition of plagiarism is based upon the one framed in North American

and Western European academic cultures in which an Anglo-Saxon heritage is prevalent.

Plagiarism, then, in the United States is based upon a Western or Anglo-Saxon idea, and does not

acknowledge that other cultures may not share its definition or believe that ideas and language

can be owned. This opens the door to examining plagiarism as an ethical issue centered in a

Western academic moral system of thinking about intangible or intellectual rights, especially

with regard to second language writing pedagogy.

Conceptualizations of plagiarism

Flowerdew and Li (2007) draw attention to a number of caveats in any contemplation of

what constitutes plagiarism brought forward by Currie (1998):

.the need to appreciate the (postmodernist) belief in the intertextual nature of

discourse, the belief that no writer can be the sole originator or his or her own words or

ideas: the need to acknowledge the cultural and ideological implications of the traditional

Western (especially Anglo-Saxon) definition of plagiarism (a definition which fails to

acknowledge alternative cultural conceptions of acceptable practice and that may lead to

problems in dealing with students [especially ESL students] plagiaristic behaviors; and

the potential usefulness of distinguishing between the borrowing of words vs. the

borrowing of ideas when analyzing specific cases of textual borrowing. (p. 163)

Likewise in a study by Abasi and Graves (2008, p.230) on how university plagiarism policies

interacted with international graduate students development of identities as authors in their

academic writing, the authors found that the language used in plagiarism policy serving to

demystify academic writing had a negative effect on those students who were learning about

and becoming familiar with the genre of academic writing. The argument in this study was

framed around professors expectations that graduate students, including international students,

Plagiarism discourse

adopt an authorial stance in their writing. Many professors interviewed in the study lamented

that their international students writing often exhibited heavy borrowing and paraphrasing from

published sources with little evidence of creativity or authorial voice.their own voices were

almost completely marginalized by the authoritative voices of published authors (p. 226). This

brings up the issue of how to effectively convey to students what is expected in academic writing

and what constitutes plagiarism.

Forms of plagiarism

Plagiarism is a multi-layered phenomenon. It comes in many forms and likewise is the

result of many different intentions. There are obvious forms of plagiarism which are done with

intention, such as purchasing a paper from a website and turning it in as your own, direct

copying of anothers words and claiming them as your own, and self-plagiarism, or turning in

ones own work for more than one assignment, i.e. receiving credit more than once for the same

piece of work. These forms of plagiarism can be thought of as prototypical forms of plagiarism

which include intention to deceive.

Researchers have identified two contingencies related to plagiarism in writing. The first

contingency is intentionality, which the previous examples of prototypical plagiarism exhibit.

This contingency hedges on the degree to which an unattributed or misattributed writers use of

anothers work is deliberate. This can include mismatched work and source attribution,

inappropriate use of the citation conventions, and incomplete or incorrect adaptations of an

original passage. The second contingency has to do with culpability or the level of fault or moral

responsibility that a writer has in committing these types of plagiaristic acts (Jocoy & DiBiasi

2006, p.2).

One common form of plagiarism is textual plagiarism, which Pecorari (2003, p. 318)

defines as using the language and ideas from a source without (sufficient) attribution. This type

of plagiarism varies in intentionality. Pennycook (1996, p.202) illustrates an experience with

Chinese students where a student wrote a word-for-word memorized biographical account of

Abraham Lincoln which came from the class text. In this account the student unintentionally

plagiarized and did not try to hide the fact that they copied from memory. When Pennycook

(1996, p. 202) asked the student about copying the student reported feeling:

.rather fortunate that I had asked them to write something which he already knew.

Sitting in his head was a brief biography of Abraham Lincoln, and he was quite happy to

produce it on demand.

This account not only illustrates textual plagiarism, but also demonstrates how cultural beliefs on

ethics in writing make defining something as plagiarism relative, especially with students from

cultures where rote learning and memorization are seen as positive learning activities and in

Plagiarism discourse

some cases a sign of superior intellect. This exemplifies how there are degrees in the

prototypicality of textual plagiarism and cultural factors may play into the degrees of

intentionality and culpability at work.

Another form of plagiarism is referred to as patchwriting. Howard (2000) defines

patchwriting as: copying from a source text and then deleting some words, altering grammatical

structures, or plugging in one-for-one synonym substitutes (as cited in Pemberton 2000, p.80).

This form of plagiarism is classified as unintentional plagiarism and nonprototypical plagiarism.

However, Howard brings up the paradox in using terms like unintentional plagiarism by

pointing out that since plagiarism, as a subset of academic dishonesty, is seen as an ethical issue

where being dishonest means a lack of ethics or acting unethically. But she also points out that

by calling it unintentional we assert that it is committed by a writer who is ignorant of U.S.

academic ethics. It is unintentionally unethical (p. 80). Comparing patchwriting to purchasing

a completed paper from, say an internet paper mill, demonstrates a dichotomy between

unintentional and intentional plagiarism, however, because these are both classified under

academic dishonesty (plagiarism) they are both defined as unethical. The respective terminology

is problematic because it attempts to classify many extremely contextually situated events under

one reference.

Howard (2000) attributes patchwriting as a form of plagiarism in second language writing

where limited reading comprehension may be the cause, in that the student doesnt fully

understand what she is reading and thus cant frame alternative ways for talking about ideas. Or

the student understands what she is reading but is new to the discourse (quoted in Pecorari

2003, p. 320). This quote speaks to the possibility that second language learners use

patchwriting to supplement their writing because they are novice writers and are not familiar

with how to write with an authorial stance in a new discourse.

Flowerdew and Li (2007, p.164) use the term language re-use to describe Chinese novice

scientists textual copying strategies in a study they conducted. In their opinion this term, while

describing a similar phenomenon to patchwriting, removes the stigmatizing effect of language

entailed by the term plagiarism. Intertextuality is yet another term used to reframe the binary

effect of most plagiarism discourse. Intertextuality refers to the notion that all texts are related to

prior texts which include ideas on the subject or research of the text being written, therefore

some degree of textual borrowing is inevitable. This notion speaks to ideas about originality and

ownership. Any new writing that is grounded in research will unavoidably and inadvertently

include some form of borrowing. Chandrasoma et al. (2004, p. 173) claim that intertextuality

(i.e. textual borrowing) is endemic to all writing. Viewing writing as a product which is

influenced by and therefore linked to previous writing further blurs the lines of what constitutes

plagiarism and the ethical judgments that ensue. In light of the forms of plagiarism highlighted

Plagiarism discourse

in this section it is useful to consider these forms through the lens of a published plagiarism

policy.

Academic dishonesty: the institutional level

There are a number of researchers trying to understand and identify reasons why

international students may have higher tendencies for unacceptable source appropriation. One

place to start to analyze this issue could be within the language of a university plagiarism policy.

Institutions of higher education have a responsibility to uphold academic standards in order to

ensure academic integrity. Plagiarism is a subcategory within their guiding principles in

ensuring integrity. The following excerpt is taken from the policy handbook for a medium-sized,

public university located in the Western United States:

Plagiarism Plagiarism includes the copying of language, structure, images, ideas, or

thoughts of another, and representing them as ones own without proper acknowledgment

and is related only to work submitted for credit; the failure to cite sources properly;

sources must always be appropriately referenced, whether the source is printed, electronic

or spoken. Examples include a submission of purchased research papers as ones own

work; paraphrasing and/or quoting material without properly documenting the source.

(Colorado State University policies and guiding principles 2014, p.

9)

The language in this policy seems to reduce academic dishonesty to issues in properly

acknowledging sources of knowledge. In effect, the language in this policy suggests that as long

as writers have proper citation they can avoid plagiarism. In comparison, the policy from an

internationally recognized private university addresses issues other than citation, including

authorial stance. The policy states:

All work submitted for credit is expected to be the students own work. In preparation of

all papers and other written work, students should always take great care to distinguish

their own ideas and knowledge from information derived from other sources. The term

sources includes not only published primary and secondary material, but also

information and opinions gained directly from other people.

(Harvard University guide to using sources, 2014)

The difference between the policies, and the point of the comparison, is that the second policy

acknowledges forms of plagiarism beyond citation and in effect promotes students taking a

careful authorial stance in their writing. Abasi and Graves (2008, p. 230) argue that the omission

of information (to students) on the rhetorical uses of texts in academic writing as a collaborative

act of knowledge construction fails to convey an important core assumption that those privy to

professional writing practices adhere to,

Plagiarism discourse

namely, that knowledge is contingent, and that all published sources, regardless of their

authors, are to be approached as provisional claims to truth that are always subject to

rational scrutiny

The failure of the first policy to recognize the importance of students distinguishing their own

ideas in their writing, leaves a lot of gray area in the conversation on what is and what is not

plagiarism. It also may create a scenario where the professor who suspects the type of

plagiarism highlighted in the second policy must be the one to open a dialogue with students

about inserting their own ideas and responding to sources, possibly sending the message that not

distinguishing your ideas from source ideas is not acceptable for this particular professor but may

be in other contexts. In the case of international students, instruction on how to use sources to

cultivate an authorial stance in their writing is essential in ESL instruction of academic writing.

Classroom texts as conveyers of best practices in academic writing

This portion of the paper focuses on an analysis of classroom texts used in an Intensive

Academic English program. The texts are used in the two highest levels of writing classes in the

program. Specifically, the sections defining plagiarism and how to avoid plagiarism are

analyzed.

The first text, Academic Writing for Graduate Students, by Swales and Feak (2004, p.

173) lists the following approaches to writing as plagiarizing approaches:

1. Copying a paragraph as it is from the source without any acknowledgement.

2. Copying a paragraph making only small changes such as replacing a few verbs or

adjectives with synonyms.

3. Cutting and pasting a paragraph by using the sentences of the original but leaving one

or two out, or by putting one or two sentences in a different order.

4. Composing a paragraph by taking short standard phrases from a number of sources

and putting them together with words of your own.

5. Paraphrasing a paragraph by rewriting with substantial changes in language and

organization, amount of detail, and examples.

This list is juxtaposed with an example for using sources which would produce and constitute

acceptable original work (p.173):

Quoting a paragraph by placing it in block format with source cited.

This may mislead students into believing that quotation is the only safe strategy to avoid

plagiarism. Further, example 4 is mute on what constitutes short standard phrases.

Plagiarism discourse

The second text, Sourcework: Academic writing from sources, by Dollahite and Haun

(2012), makes little mention of the word plagiarism in its section on attributing sources. Instead,

the section is headed under Documenting Your Evidence. It gives the following rationales for

documenting sources:

1. To let the reader know that you have carefully researched your ideas.

2. To tell the reader where to find the original if she wants to learn more about your

topic.

3. To avoid plagiarism, a serious offense in academic writing in the United States.

(p. 123)

Although this text does not define or give clear examples of what constitutes plagiarism it does

present a good argument for why documenting sources is good for writer credibility and

maintaining rapport with the audience in that they are informed of the sources of information in

the paper. The rest of the chapter focuses on APA conventions for documentation of sources.

The third text, Academic Encounters 4:Reading and Writing, by Seal (2012) makes only

one explicit mention of plagiarism in one of its many sections on paraphrasing as a writing skill.

In this section paraphrasing as a writing skill is described as follows:

Sometimes when you have a writing assignment, you read something that someone else

wrote that has information and ideas that you want to include in your writing, too. You

cannot simply copy this persons words into your writing and pretend that they are your

own. This is called plagiarism, and it is considered to be a serious offense. However,

you can paraphrase. Paraphrasing involves understanding the meaning of what someone

else wrote and the using your own language to express the same thing. .the key to

writing a good paraphrase is not only to use synonyms, but also to change the sentence

structure. (p.80)

This seems to send the message that paraphrasing does not require citation. Further, this

description seems to correspond with what Howard (2000, cited in Pemberton, 2000) attributes

as patchwriting, a form of unintentional plagiarism and what Swales and Feak (2004) attribute as

a form of plagiarism (see item 5 in their list). The skill of paraphrasing is reviewed again in a

later chapter by stating:

You use paraphrasing when you include someone elses ideas in your own writing. You

can use paraphrasing when you encounter a difficult piece of text. Rewriting the text in

your own words is a way to deeply interact with the text as you struggle to understand it.

(p.126)

Plagiarism discourse

Again, this passage suggests that unattributed paraphrasing does not constitute plagiarism. The

writing skill of quoting from an original source is described in the last chapter of the text by

stating:

In developing writing skills you have learned how to paraphrase.In each case, you

have learned how to avoid plagiarizing by using your own words to include information

and ideas from another writer..A third way to include another writers information

and ideas is to use quotations, that is, the actual words that the writer used..Also, using

the writers actual words will show your instructor that you have read and understood a

reading very thoroughly and thought critically about it. (p.188)

This passage is followed by a very general description of citation conventions. The message that

this passage seems to send, however, is that using quotations and attributing them to a source

avoids plagiarism and demonstrates to your instructor (audience) that you understand what you

read in the original source. There is no indication to students, in this passage, as to how

quotations affect their authorial stance or credibility as writers. Also, this passage could be

construed as promoting an unlimited use of quotations.

Stance in academic writing

Biber et al. (1999, p. 966) defines stance a linguistic device where speakers and writers

express personal feelings, attitudes, value judgments, or assessments. Biber (2006, p. 99)

refers to stance expressions as those which convey to the audience a speakers attitude, how sure

they feel about the reliability of certain information, how they obtained access to this

information, and most importantly what perspective or viewpoint they are representing or taking

up in their writing. Stance, then, is a way in which writers convey a part of themselves to their

audience. Stance is referred to by many terms including: evaluation (Hunston and Thompson,

2000), attitude (Halliday, 1994), epistemic modality (Hyland, 1998), appraisal (Martin, 2000);

White, 2003), stance (Biber and Finegan, 1989; Hyland, 1999), and metadiscourse (Crismore,

1989; Hyland and Tse, 2004) all of which describe a similar phenomenon accounting for an

interpersonal dimension of writing (all cited in Hyland 2005, p. 174). Effective academic

writing should take into account audience and the potential questions or disagreements which

may arise from their writing. In this way writers are simultaneously trying to make a claim,

comment on its truth, establish solidarity and represent credibility(Hyland 2005, p. 177).

Where second language learners are concerned, especially in light of the writing strategies

highlighted in learner texts, stance and its importance when citing and paraphrasing research

seems to present a necessary but often missing component in second language writing pedagogy.

Plagiarism discourse

10

Discussion and Implications

According to Open Doors Data from the Institute of International Education, the number

of international students enrolling in institutions of higher education in the United States has

been increasing by about 8% every year. In 2014, there were approximately 886,000 students

studying in universities across the United States with the largest portion of these students from

China. From a linguistic perspective, there are many expectations of these students in an English

medium classroom, one of which is the ability to understand, analyze and synthesize research

into their academic writing. There is also an expectation for these learners to be able to

synthesize this research in a way that also incorporates an element of their own stance. These

expectations can be particularly difficult for some writers as they represent western-centric

conventions and are expected by virtue of the genre and discipline to add to knowledge.

Citations are a device by which a writer can be interactive and evaluative in their own writing.

Citations play a key role in all academic writing that is research based. Citations demonstrate

how a new proposition or piece of evidence is grounded in previous research and ongoing

knowledge. Citations help writers to project themselves into their own writing through their

support or challenge to the contributions of others involved in similar research. Citations, then,

can be used as devices to give a writer a credible stance in their writing.

The implications that can be drawn from the research used in the paper are broad. From

a second language teaching perspective, one implication might be examining the concept of

plagiarism in relation to international students who may not share in the idea that words and

ideas can be owned. Further, as these students are learning how to write and are simultaneously

seeking membership into a new discourse community through their writing, it seems extra unfair

to label them plagiarizers. A second implication, especially in light of a repeated concern for

international students tendency to not attribute language or ideas to their sources, may be drawn

from the review of the sources for dispelling this type of knowledge, in that, there doesnt seem

to be a clear or empirical pedagogy for teaching learners what constitutes plagiarism and what

does, only strategies for avoiding it. The research used as a basis to form these implications

similarly suggests that decisions about whether a second language learner has plagiarized should

be related to questions of student reading comprehension, student writing development, ways in

which writing strategies are conveyed to students, whether stance and authorial voice is a part of

these conversations, and ways in which citation conventions and their imperativeness for

credibility are emphasized to students. Chandrasoma et al. (2004, p. 172) echo this by

suggesting that plagiarism and textual borrowing cannot be dealt with in terms of only detection

and prevention, or of simply teaching the correct citation practices, because it is centrally

concerned with questions of language, identity, education, and knowledge.

Plagiarism discourse

11

References

Abasi, A. R., & Graves, B. (2008). Academic literacy and plagiarism: Conversations with

international graduate students and disciplinary professors.Journal of English for

Academic Purposes, 7(4), 221-233.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., Finegan, E., & Quirk, R. (1999). Longman

grammar of spoken and written English. London/New York: Longman.

Biber, D. (2006). Stance in spoken and written university registers. Journal of English for

Academic Purposes, 5(2), 97-116.

Chandrasoma, R., Thompson, C., & Pennycook, A. (2004). Beyond plagiarism: Transgressive

and nontransgressive intertextuality. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 3(3),

171-193.

Colorado State University. (2014). Policies and guiding principles. Retrieved from:

http://www.catalog.colostate.edu/Content/files/2014/FrontPDF/1.6POLICIES.pdf

Dollahite, N. E., Haun, J. (2012). Sourcework: Academic writing from sources. 2nd ed. Boston:

Heinle / Cengage Learning.

Flowerdew, J., & Li, Y. (2007). Plagiarism and second language writing in an electronic age.

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 161-183.

Harvard University Academic Dishonesty and Plagiarism. (2014). Retrieved from:

http://hms.harvard.edu/departments/office-registrar/student-handbook/4-student-conductand-responsibility/409-academic-dishonesty-and-plagiarism

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse.

Discourse studies, 7(2), 173-192.

Institute of International Education. Retrieved from: http://www.iie.org/Research-and

Publications/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students

Jocoy, C. L., & DiBiase, D. (2006). Plagiarism by adult learners online: A case study in

detection and remediation. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning, 7(1).

Plagiarism discourse

12

Pecorari, D. (2003). Good and original: Plagiarism and patchwriting in academic second

language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(4), 317-345.

Pemberton, M. A. (2000). The ethics of writing instruction: Issues in theory and practice.

Stamford, Conn.: Ablex Pub..

Pennycook, A. (1996). Borrowing others' words: Text, ownership, memory, and

plagiarism. TESOL quarterly, 30(2), 201-230.

Seal, B. (2012). Academic Encounters 4: Reading and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Swales, J. M., Feak, C. B. (2004). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and

skills. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- R&W Thematic UnitDocumento28 pagineR&W Thematic Unitapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theme Lesson PlanDocumento2 pagineTheme Lesson PlanRyan Kane100% (1)

- Morphology and Syntax Observation Report and ReflectionDocumento9 pagineMorphology and Syntax Observation Report and Reflectionapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Architectural Design-Collective Intelligence in Design (2006-0910)Documento138 pagineArchitectural Design-Collective Intelligence in Design (2006-0910)diana100% (3)

- Task 3 Assessment CommentaryDocumento9 pagineTask 3 Assessment Commentaryapi-317861393Nessuna valutazione finora

- BSES Eco Outreach STORY TELLING Activity DesignDocumento2 pagineBSES Eco Outreach STORY TELLING Activity DesignMigz AcNessuna valutazione finora

- Communicative Language TeachingDocumento37 pagineCommunicative Language TeachingAulya Ingin Bertahan80% (5)

- Learner Strategy Project ProposalDocumento10 pagineLearner Strategy Project Proposalapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Observation ReportDocumento21 pagineObservation Reportapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Test ProjectDocumento37 pagineFinal Test Projectapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Journals AssessmentDocumento6 pagineLearning Journals Assessmentapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pedagogical ContributionDocumento8 paginePedagogical Contributionapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- My Philosophy On AssessmentDocumento2 pagineMy Philosophy On Assessmentapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Responses To Frequently Asked QuestionsDocumento4 pagineResponses To Frequently Asked Questionsapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Article DiscussionDocumento8 pagineArticle Discussionapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing VocabularyDocumento30 pagineAssessing Vocabularyapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Comparatives and EquativesDocumento10 pagineComparatives and Equativesapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Textbook ReviewDocumento10 pagineGrammar Textbook Reviewapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Workplace English Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineWorkplace English Lesson Planapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- CotesoldemonstrationDocumento32 pagineCotesoldemonstrationapi-275162743Nessuna valutazione finora

- Semantics of PrepsDocumento11 pagineSemantics of Prepsapi-275162743100% (1)

- Parent AFD 7802021 1972018224118829Documento1 paginaParent AFD 7802021 1972018224118829abjiabhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Master of Business Administration (MBA) Schedule: Kempinski Hotel Al KhobarDocumento2 pagineMaster of Business Administration (MBA) Schedule: Kempinski Hotel Al KhobarEyad OsNessuna valutazione finora

- PEMEA NewsletterDocumento8 paginePEMEA NewsletterCarlo MagnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Certificate of Participation: Enrico R. GalangDocumento22 pagineCertificate of Participation: Enrico R. GalangSammy JacintoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fsa Ready Assessment - Book 1Documento42 pagineFsa Ready Assessment - Book 1api-3271385300% (1)

- Developmental Stages: Early Childhood: Ages 3 To 6 Yrs Cognitive LandmarksDocumento5 pagineDevelopmental Stages: Early Childhood: Ages 3 To 6 Yrs Cognitive LandmarksHassan JaseemNessuna valutazione finora

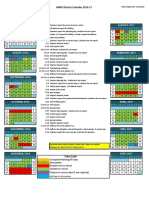

- 2016-17 District CalendarDocumento1 pagina2016-17 District Calendarapi-311229971Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2 Process-Oriented and Product-Oriented PDFDocumento31 pagine2 Process-Oriented and Product-Oriented PDFPearl QuebrarNessuna valutazione finora

- IV Mothers DayDocumento3 pagineIV Mothers Dayanabel lNessuna valutazione finora

- Aaryans Class 11 Health & Physical Education P.A.-I (2021-22) MCQs & Short QuestionsDocumento2 pagineAaryans Class 11 Health & Physical Education P.A.-I (2021-22) MCQs & Short QuestionsJatin GeraNessuna valutazione finora

- CBCS Syllabus Ecology FinalDocumento49 pagineCBCS Syllabus Ecology FinalRahul DekaNessuna valutazione finora

- DownloadDocumento1 paginaDownloadRasika JadhavNessuna valutazione finora

- MECH-4705 CourseOutline Fall2016Documento4 pagineMECH-4705 CourseOutline Fall2016MD Al-AminNessuna valutazione finora

- Full - Harmony in The Workplace - Delivering The Diversity DividendDocumento30 pagineFull - Harmony in The Workplace - Delivering The Diversity DividendSafarudin RamliNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022-23 BUSI 1324-Managing Strategy Module HandbookDocumento23 pagine2022-23 BUSI 1324-Managing Strategy Module HandbookSamrah QamarNessuna valutazione finora

- Karl TommDocumento2 pagineKarl TommKok Sieng Joshua ChangNessuna valutazione finora

- DownloadfileDocumento7 pagineDownloadfileFernanda FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- Frontlearn Institute Fee Structure for Culinary Arts, ICT and Business Management CoursesDocumento1 paginaFrontlearn Institute Fee Structure for Culinary Arts, ICT and Business Management CoursesNjihiaNessuna valutazione finora

- PRC Nurses' Application Form (NAF) : First-TimersDocumento2 paginePRC Nurses' Application Form (NAF) : First-TimersMe-i Gold Devora TobesNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan With ModificationsDocumento2 pagineLesson Plan With Modificationsapi-250116205Nessuna valutazione finora

- Al Lamky, 2007 Omani Female LeadersDocumento23 pagineAl Lamky, 2007 Omani Female LeadersAyesha BanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Berkeley Response Letter 9.21.20 PDFDocumento3 pagineBerkeley Response Letter 9.21.20 PDFLive 5 NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Loose Parts: What Does This Mean?Documento2 pagineLoose Parts: What Does This Mean?kinderb2 2020nisNessuna valutazione finora

- Educational Medical, Health and Family Welfare Department, Guntur-Staff NurseQualification Medical Health Family Welfare Dept Guntur Staff Nurse PostsDocumento4 pagineEducational Medical, Health and Family Welfare Department, Guntur-Staff NurseQualification Medical Health Family Welfare Dept Guntur Staff Nurse PostsTheTubeGuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Application Summary Group InformationDocumento12 pagineApplication Summary Group InformationKiana MirNessuna valutazione finora