Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Classical Hollywood Cinema, Narrational Principles and Procedures

Caricato da

AthenaMor0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

1K visualizzazioni10 pagineA text of David Bordwell for the narration of the cinematic procedures.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoA text of David Bordwell for the narration of the cinematic procedures.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

1K visualizzazioni10 pagineClassical Hollywood Cinema, Narrational Principles and Procedures

Caricato da

AthenaMorA text of David Bordwell for the narration of the cinematic procedures.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 10

Y

David Bordwell

Classical Hollywood Cinema:

Narrational Principles and Procedures

‘Thee aspects of narrative can, atleast provisionally, be kept distinct. A narrative

can be studied as representation, how it refers to or signifies a world or body of

ideas. This we might call the “semantics” of narrative, and it is exemphiied in

most studics of characterization or ralism. A narrative can also be studied as a

sinature, the way its components combine to create a distinctive whole. An

example of this “syntactic” approack would be Vladimir Propp? morphology

of the magical fairy tale Finally, we can study a narrative as an act, a dynamic

process of presenting a story to a perceiver. This would embrace considerations

cof source, function, and effect; the temporal progress of information ot action;

and concepts like the “narrator” Thisis the study of naration, the “pragmatics”

- ofnarative phenomena. What follows concerns itself with narration in classical

Hollywood cinema between 1917 and 1960, but it does not singlemindedly stick

{this aspect. Its common for any one narrative analysis to focus on one aspect

= but to bring in others as needed. Lévi-Strauss, for instance, uses a concept of

| narrative structure to disclose deeper levels of meaning, what the myth repre-

seats syntax isa tool for revealing semantics. In this essay, I introduce issues of

[representation (especially denotative representation) and structure (especially

damatargical structure) in order to highlight how classical Holly wood narration

configuration of normalized opiiciisToriepresenting the

Since this is a précs of an

Adapted from David Bordvell, Nemation in he Fiction File (Madison: University of Wisconsin

1985), reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press.

18 David Bordwell

ad hoe

body of research, it will have an unfortunately programmatic, ad

Sir about i, but the readers can refer to the end ofthe arte forthe evidence

‘upon which these claims are based.* Unusual nomenclanure i glossed below.*

‘The Straight Corridor

“The classical Hollywood film presents psychologically defined individuals who

Tragletslve deat problem ort stain spectc gels Inthe couse of

this struggle, the characters enter into conflict with others or with exter:

ireumstances. The story ends with a decisive victory or defeat, a resolution of

the problem and a clear achievement or nonachievernent of the goals. The

principal causa is thus the character, distincive individual endowed

‘with an evident, consistent batch“of WANS, GUAGE and behaviors. Although

the nema inherits many conventions of portrayal from theater and literature,

the character types of melodrama and popular fiction get fleshed out by the

addition of unique motifs, habits, or behavioral tics. In parallel fashion, the star

system has as one of its functions the creation ofa rough character prototype

‘which is then adjusted to the particular needs of the role. The most “specified”

character is usually the protagonist, who becomes the principal causal agent,

the target of any narrational restriction, and the chief object of audience identi-

fication, These features ofthe syuzhet come as no surprise, though already there

sre importa deren from oer mations eves (eg, the compare,

a ‘consistent and goal-oriented characters in art-cinema narration)

Sf sa mas dat daa one conforms most closely to the “emo

story” which story-comprehension researchers posit as normal for our culture

‘abule: Russian formalist term for the narrative events in causal chronological sequence.

Sst on ri tm fr eran of fb evens inthe tn we

ere eae etna ae ec eae pa

Fee het where naraon phi os mngeid dp oftnowag

Se eet kh te emda nove hve the pene

Se re eu ae macs whee we commits Gb

i exacting tix procs of ome io fncon nee

Te nn: jtyingthe pens ofan deny vat of coniy wih

Se, jing te proms fan elaen by i eling ttn to eas

Sree Se kaon: jhng he psec of chet by fen to the ego of

ae er epee to ge cameron)

Classical Hollywood Cinema 19

In fabula terms, the reliance upon character cause and effect and the definition

of the action as the attempt to achieve a goal ae salient features of the eanonic

format.* At thelevel ofthe syushet, the classical film respects the canonic pattern

of establishing an inital state of affairs which gots violated and which must then

besot right. Indeed, Hollywood screenplzy-writing manuals have long insisted

‘ona formnla which bas been revived in recent structural analysis: the plot consists

of an undisturbed stage, the cisturbance, the struggle, and che elminatoit ot

‘edisturbance.* Such a syuzher pattern is the inheritance not of some monolithic”

‘onstruct called the “novelistic” but of specific bistorical forms: the well-made

‘play the popular romance, and, crucially the late nineteenth-century short story.’

‘The characters’ causal interactions are thus to a great extent functions of such

overarching syuzhet/fabula patterns,

Jn classical fabula construction, causality is the prime unifying principle

Analogies between characters, settings, and situations are certainly present, but

tthe denotativeleuel any parallelism is subordinated to the movement of cause

and sffect° Spatial configurations are motivated by realism (a newspaper office

Imust contain desks, typewriters, phones) and, chiefly, by compositional necessity

(che desk and typewriter will be used to write causally significant news stories,

the phones form crucial links among characters). Causality also motivates tem

poral principles of organization: the syuzhe represents the order, frequency, and

duration of fbula events in ways which bring out the salient causal relations.

1 This process is especially evident in 2 device highly characteristic of classical

‘narrition—the deadline. A deadline can be measured by calendars (Areund the

Wild in Eighty Days), by clocks (High Noon), by stipulation (*Youlve got a week.

but not 2 minute longes”), or simply by cues that time is running out (the last-

‘minute rescue). That the climax ofa classical film is often a deadline shows the

structural power ing dramatic duration as the time i takes to achieve or

Sal to achieve a goal. Peet

‘Usually the classical syuzhet presents 4 double causal stmacuure, 179 plot li

one in hing bose Goy/gil, husband/wife), the other

‘nvelving another sphe cK, War, a mission or quest, other personal rela~

ips. Each line will possess a goal, obstacles, and a climax. In Wild and

Wooly (1917), the hero Jeff has two goals—to live a wild western life and to

court Nell, the woman of his dreams. The plot can be complicated by several

lines, such as countervailing goals (the people of Bitter Creek want Jeff to get

them a railroad spur, a crooked Indian agent wants to pla robbery) or multiple

romances (as in Footlight Parade and Meet Me in St. Loui), In most cases, the

romance sphere and the other sphere of action are distinct but interdependent.

‘The plot may close off one lin before the other, but often the two ines coincide

at the dimax; resolving one triggers the resolution of the other. In His Gi

the reprieve of Earl Williams precedes the reconciliation of Walter and

‘lly, but iti also the condition of the couple’ reunion.

‘The syuzhet is always broken up into segments. In the silent era, the typical

20 David Bordwell

Hollywood flim would contain between 9 and 8 sequences in che Sou Ss

between 14 and 35 (with postwar

Speaking roughly, there are only. £0. €YPeS ‘of Hollywood segments. sum

uae (compromising Mets third, fourth, and ght, syntagmatic type) am

SSeenes” (Metz filth, sith, seventh, and eighth fYPss y Hollywood natration

ently, demazoates in scenes by neodasicl critena ‘of time (continuous,

Fo nt ofa complex braiirg of casa ines (s in Rivet) or 29 sb

braking ofthem (asin Antonioni, Godard, oF Bresson) the classical Hollywood

distinct cause-effect phase). The bounds ‘in spins them out in smooth, careful linearity. S

“standardized puncruations Gssolve, fi A

arrest chat the casi segment tends alo to define sS5° MESS,

sically (through internal repetitions of style oF #0Fy material) and

mie rocosmicaly (by parallels with odber segments of the Sr magnitude)"

rane remember that each film establishes is own sie of segrncato,

J cyurhet which concentrates on singe lode over limited a duration

(Co, the one-night-in--haunted-house film) may reste eB nS by character

tentrances or exits, 2 theatrical liaison des snes. Ti a film which spans decade 4

and many locales, + ries of dissolves from one stnall action to another will net

need for a logical wrap-up. ‘Sl, there are enough instances of unmotivated or

jnadequate plot resolutions to suggest * ‘second hypothesis: chat the classical

ve ot all that structurally. decisive, being, a mre, les aba read

‘The clesical segment is not 2 sealed entity, Spaally and cemporally itis ee jstmentof that world knocked avy ip the previous eighty minutes. Parker

closed, but easily ic open, It works to advance the causal Progress £5 ME Tiler suggests that Hollywood regards all endings 25 © sirely conventional,

Fauld offen, lke the charade, of an infantile logic?" Hlere again SE 8

theimportane ofthe plotline involving heterosexual romances. Is significant

‘hat of yoo random ollyqyooa films, over 69 ended with a display

oe Fomine couple —the cliché happy ending, often wih “Cinch

‘many more could be said to end happily "Thus an extrinsic norm, the need

and ry He plot ina way that provides “pore juton” beoomes 2 struct}

ede wv mire or se motivation into its proper sot, the plows,

feany marae, as Mee Sternberg pots out, when the syuzhef ends strongly

preast by convention, the-composiionalatention fs of the retardation of

eee nocomplished by the middle portions; the tt will then “acco for

aay tadason in quari-mimetic terms by Placing the causes for dehy

the peer Fave word ielf and turning the middie into the bulk of the

Fars ow Ac times, however, the motivation is constructed to be

Efrat, and a discordance between preceding causality and 130

rmant becomes noticed ap ideological dfficolty; such isthe ate wath films

BE You Only Live Once, Suspicion, The Woman in ‘the Window, and The Wrong

ae ne We onght, then, tobe prepared for either askllfal tying up of a Joos

eat gra more or Jess miracalous appearance of what Brecht calle bowrgsos

Feenouck mounted messenger. “The mounted messenger guarsniess YOU &

truly undisturbed appreciation of cren the most intolerable conditions 8° isa

he qua non for a literature whose sine qua non i that it leads nowhere"

ea aera ending may bea soe spot in another respect. Even ifthe ending

recoles the two principal causal lines some comparatively minor issues mY

open up new developments ® The pattem of this forward momentum is quite

oper OF Ene montage Sequence tends to function 28a tansiona) SUNT g

CSinpresing 2 single causal development but the sane of character action—

he building block of clasical Hollywood dramaturgy “is mee intricately

aa a ei soon displays dict phases. First comes the exposition

crepes dhe me, Pace, and evant character theisS=vis! BORA

aance pecrment states of mind (asually as 2 result of previous sen) WP the

amydle of the scene, characters act toward their goals: chey struggle, make

vheicce, make appointments, set deadlines, and plan future evens Inthe course

Seis the dascieal soene continues or closes off cause-effect developments let

“hile also opening up new causal lines for fature

At least one | ¢ of action must be let suspended, in order 9

motivate the > the next scene, “hich picks up the suspended line [fen

mae logue hook”) Hence the famous “Lnearity_of dase ‘construction

eee racterstic of Soviet montage films (which often refuse 1 domay

2 tat any) or of artecinema narration (wih ts ambiguows iterpley of |

subjectivity and objectivity)

aeece a simple example. In The Killers (1946), the insurance invest

‘Rind as boos hearing Lieutenant Labinsky’s2ccount of Ole Andersons early

life. At the end of the scene, Lubinsky tells Riordan that they'e burying Ole

ae PS Thi dangling cause fads to the next scene, st in the emery. 8

Mablishing shor provides spatial exposition. While the clergyman intone: the

cn ve ordan aks Lubinsky the Wentiry of various mourners. The

22 David Bordwvell

still be left dangling. For example, the fates of secondary characters may go

unsettled. In His Gil Friday, Earl Williams is teprieved, the corrupt adminis-

tration wall be thrown out of office, and Walter and Hildy are reunited, but we

never leam what happens to Molly Malloy, who jumped out a window to

distract the reporters. (We know only that she was alive after the fll.) One could

argue that in the resolution of the main problem we forget minor matters, but

this is only a partial explanation. Our forgetting is promoted by the device of

closing the film with an epilegue a brief celebration of the stable state achieved

by the main characters. Not only does the epilogue reinforce the tendency

toward a happy ending; it lso repeats connotative mori that have rom through-

cout the film. His Gil Friday closes on a brief epilogue of Walter and Hildy

calling the newspaper office to announce thei remarriage. They learn that 2

strike has started in Albany, and Walter proposes stopping off to cover it on

their honeymoon. This plot twist announces a repetition of what happened on

their frst honeymoon and recalls that Hildy was going to marry Bruce and live

in Albany. As the couple leave, Hildy carrying her suitcase, Walter suggests that

Brice might put them up. The neat recurrence of these motifs gives the narration

a strong tity, when such details are so tightly bound together, Molly Malloy’

fate is more likely to be overlooked. Perhaps instead of “dosure” it would be

better to speak of a “closure effec,” or even, if the strain of resolved and

unresolved issues seems strong, of “pseudo-closure” At the level of extrinsic

norms, though, the most coherent possible epilogue remains the standard to be

aimed at.

Commonplaces like “transparency” and “invisibility” are on the whole un-

helpful in specifying the narrational properties of the classical film. Very gen-

erally, we can say that classical narration tends to_be omniscient, highly

communicative. and _ouly..moderately. self-conscio is, the narration

knows more than any or all characters, it conceals relatively litle (chiefly “what

will happen next”), and it seldom acknowledges its own address to the audience

But we must qualify this characterization in two respects. First, generic fictors

‘often create variations upon these precepts. A detective film will be quite

restricted in ts range of kmowledge and highly suppressive in concealing causal |

information. A’ melodrama like In This Our Lif can be slightly more sel

conscious than The Big Slep, especially in its use of acing and music. A rascal

__Will contain codified moments of self-consciousness (e.g., when characters sing

“directly out at the viewer). Second, the temporal progression of the syuzhet

‘makes narrational properties uctuste across the film, and these too are codified.

‘Typically, the opening and closing of the film are the most self-conscious,

omniscient, and communicative passages. The credit sequence and the first few

shots usually bear traces of an overt narration. Once the action has started,

however,the narration becomes more covert, letting the characters and theit

interaction take over the transmission of information. Overt narrational activity

retums at certain conventional moments: the beginnings and endings of scenes

Classical Hollywood Cinema 23

(eg, establishing shots, shots of signs, camera movements out from or in to

Significant objects, symbolic dissolves), and that summary passage known as

the “montage sequence.” At the very close of the syuzhet, the narration may

again acknowledge its awareness of the audience (musical motifs reappear,

characters Jook to the camera or close a door in our face}, its omniscience (c.g,

‘the camera retreats to a long-shot), and its commumicativeness (now we know

all). Classical narration is thus not equally, “invisible” in every type of film nox _

_trosghout anyon lth “malsoCemncaton ae ometines Sand,

‘comumunicativeness of classical narration is evident in the way that the

syuchet handles gaps. If tims is skipped over, a montage sequence or a bit of

character dialogue informs us, ifa cause is missing, we will typically be informed

that something isnt there. And gaps will seldom be permanent. “In the begin

ning of the motion picture,” writes one scenarist, “we dontt know anything.

‘Duting the course of the story, information is accumulated, until at the end we

know everything” Again, thesc principles can be mitigated by generic moti-

vation. A mystery might suppress a gap (e.g, the opening of Mildred Pierce), a

fantasy might Ieave a cause still questionable at the end (e.g, The Enchanted

Catage). In this respect. Citizen Kane remains somewhat “uncassical"> the

natration Supplies the annswer to the “Rosebud” mystery, but the central traits

of Kane’ character remain partly undetermined, and no generic motivation

justifies this.

‘The syuzhet’s construction of time powerfully shapes the fuctuating overtness

of narration. When the syuzhet adheres to chrnnalngical order and omite the

causally unimportant periods of time, the narration becomes highly commn-

nicative and unselfconscious. On the other hand, a montage sequence compresses

political campaign, a murder trial, or the effects of Prohibition into moments,

and the narration becomes evertly omniscient. A flashback can quickly and

covertly fill a causal gap. Redundancy can be achieved without violating the

fabula world if the narration represents each story event several times in the

syusher, through one enactment and several recotuntings in character dialogue.

Deadlines neatly let the syuzhet unselfConsciously respect the durational limits

that the fabula world sets for its action. When itis necessary to suggest repeated.

or habitual actions, the montage sequence will again do nicely, as Sartre noted

‘when he praised Citizen Kanet montages for achieving the equivalent of the

“frequentative” tense: “He made his wife sing in every theater in America."

‘When the syuzhet uses a newspaper headline to cover gaps of time, we recognize

both the narrations ommiscience and its relatively low profile. (The public record

is less self-conscious than an intertitle “coming straight from” the narration.)

‘More generally, classical narration reveals its discretion by posing as an edivorial

‘intelligence that selects certain stretches of time for full-scale treatment (the

‘scenes), pares down others alittle, presents others in highly compressed fashion

(the montage sequences), and simply scissors out events that are inconsequential.

=, When fabula duration is expanded, itis done through crosscutting,

|

24 David Bordwell

‘Overall narrational qualities are also manifested in the film's manipulation of

space. Eigutcs readjusted for moderatecelf-consciousness by angling the bodies

more of less frontally but avoidi (except, of course, in optical

point-of-view passages). That no causally significant cucs in a scene are left

unknown testifies to the communicativensss of narration. Most important is

the mrratio

Spatial omnipresence.” Ifthe narration plays down its knowledge of effects and

upcoming temporal developments, it does not hesitate to reveal its ability to

change views at will. Cutting within a scene and crosscutting between vasious

locales testify to the narration’s omnipresence. Writing in 1935, 2 critic daims

that the camera is omniscient in that it “stimulates, through correct choice of

subject matter and set-up, the sense within the percipient of being atthe most,

vital part of the experience—at the most advantageous point of perception’

throughout the picrare”* Whereas Miklos Jancsos long takes create spatial

patterns that refuse omnipresence and thus drastically restrict the spectator’

knowledge of story information, classical omnipresence makes the cognitive

schema_we call “the camera’ into an idea invisible observer, feed from the

tingencis of space and time. but then discreedly confining itself to codified

teins for the sake of story intelligibility.

iy virtue of its handling of space and time, classical narration my

sistent construct into Which narration seems to

step from the outside of mise-en-scéne (Bgure = Tighing,

Setting, costume) ang ic event, which

becomes the tangible story world framed and recorded from . This

framing and recording tends to be taken as the narration itself, which can in

‘uum be more or less overt, more or kss “intrusive” on the posited homogencity

of the story world. Classical narration thus depends upon. the notion of the

invisible observer” Bazin, for instance, portrays the dassical scene as existing, 4

independently of narration, as if on a stage.™ The same quality is named by the

notion of “concealment of production’: the fabula seems not to have been

constructed but appears to have preexisted lis narrational representation, (in

Production, in some sense, it often did: for major films of the 1930s and

thereafter, Hollywood set designers created three-dimensional tabletop mock-

ups of sets within which models of cameras, actors, and lighting units could be

Phoed to predetermine filming procedures. )*

This invisible-observer narration is itself often fairly effaced. The stylistie

causes of this I shall cxamine shortly, but we can already see that dassical

narration quickly cues us to construct story logic (causality, parallelisms), time,

and space in ways that make the events “before the camera” our principal source

‘of information. For example, its obvious that Holly wood narratives are highly

redundant, but this effect is achieved principally by patterns attributable to the

‘story world. Following Susan Suleimanis taxonomy, we can see that the nar-

ration assigns the same traits and functions to each character on her or his

Classical Hollywood Cinema 25

appearance; different characters present the same interpretive commentary on

the same character or situaticn; similar events befall different characters, and so

fon. Information is for the raost part repeated by characters’ dialogue or de~

‘meanor. There is, admiztedly some redundancy between narrational commen-

tary and depicted fabula action, as when silent film expository intettles convey

Crucial information or when nondiegetic music is pleonastic with the action

(6g, “Here Comes the Bride’ in In This Our Lif). Nevertheless, in general, the

narration is so constructed that characters and their behavior produce and

tehterate the necessary story data. The Soviet montage cinema makes much

stronger use of redundancies between nartational commentary and fabula action.

Retardation operates in analogous fashion: the construction of the total fabula

‘is delayed principally by inserted lines of action (eg, causally relevant subplots,

interpolated comedy bits, musical numbers) rather than by narrational digres

sions ofthe sort found in the “God and Country” sequence of Ocober. Similarly,

causal gaps in the fabula are usually signaled by character actions (e.g, the

discovery of clues in detective films). The viewer concentrates on constructing

the fabula, not on asking why the narration is representing the fabula in this

particular way—a question more typical of art-cinema narration.

‘The priority of fabula causality and an integral fabula world commits classical

nairation to unaml presentation. Whereas art-cinema narration can blar

separating objective diegetic reality, characters’ mental states, and in

serted narrational commentary, the classical film asks us to assume clear dis-

tincriqns among these states. When the classical film restricts kuuwledge 10 a

character, as in most of The Big Sleep and Murder My Siveet, there is nonetheless

a firm borderline between subjective and objective depiction. Of course, the

‘aration can set traps for us, a in Possesed (1947), when a murder that appears

tobe objective i revealed to have been subjective (a generically motivated switch,

incidentally); but the hoax is revealed immediately and unequivocally. The

classical flashback is revealing in this connection. Its presence is almost invariably

motivated subjectively since a character’ recollection triggers the enacted rep

resentation ofa prior event. But the range of knowledge in the flashback portion is

often mot identical with that of the character doing the remembering, Ie is

common for the fashback to chow us more than the character can know (e.g,

scenes in which s/he is not present). Am amusing example occurs in Ten North

Frederik, The bulk of the film s presented asthe daughter's flashback, but atthe

‘ad of the syuzhet, back in the present, she learns for the first time information

‘wchad enconnteredin “her” fasaback! Classical lashbacksare typically “objectve"-

Seep memory msi for 2 nonchovologial svuahet atrangemen

Simalaly, optically subjective shots “anchored in an objective context.

‘One writer notes that a point-of-view shot “must be motivated by, and definitely

linked to, the objective scenes [shots} that precede and follow it”® This is one

source of the power ofthe invsible-observer effec: the camera seems always £0

fe indude character subjectivity within a broader and definite objectivity.

|

:

ale

eyhihe

eee

26 David Bordwell

Clase Holyded Cinema 27

Classical Style conventional cues, a line of dialegue). Lighting must pick out figure from

round; color must define planes; in each shot, the center of story interest will

fend to be centered in relation. t0 the: sides of the frame Sound recording is

Even ifthe naive spectator takes the style of the classical Hollywood film to be

ertaible or seamles, this is not much critical help. Whatnakes.he-sple ~inespectator through repeated setups, Momentary disorientation is ‘permissible

‘uly if modvated realistically, Discontinuous editing, as in Slavko Vorkapich’s

sequence of the earthquake in San Francisca is motivated by the chaos of the

acon depicted. Stylistic disorientation, in short, is permissible when it conveys

disorienting story situations.

{3) Classical syle consists ofa strictly ited number of particular technical

+ devices organized into a stable paradigm and ranked probabjlistically according

ieapasher demands.

A Tir Gpilste convandows of Hollywood narration, sanging from shot com-

position to sound mixing, are intuitively recognizable to most viewers, This is

because the style deploys a limited number of devices, and these devices are

regulated as alternative depictive options. Lighting offers a simple example. A

seene may be lit “high-key” or “low-key” ‘There is three-point lighting (key, fll,

tnd backlighting on figure, plus background lighting) versus single-source

Iighting. The cinematographer also has several degress of diffusion available,

Now in the abstract all choices are equiprobable, but in a given context, one

decoratively supplementing denotative syuahet demands, the use of technique alternative is more likely than its mates. In a comedy, high-key lighting is more

muse be minimally motivated by the characters interactions. “Excess” such 28 probable; a dark street will redistically motivate single-source lighting: the

ine find in Minnelli or Sirk, is often initially justified by generic convention, “ge oseup of a woman will be more heavily diffused than that of man.The

“The same holds true for even the most eccentric stylist in Hollywood, Busby invisibility” ofthe classical stylein Hollywood relies not only on highly codified,

Berkeley and Josef von Stemberg, each of whom required a core of generic [HjISTE devices but aso upon eicodifed functions in context.

motivation (musical fantasy and exotic romance, respectively) for his » Or recall the ways of framing the human figure. Most often, @ character will

| be flamed between plan-ameriat (the knees-up framing) and medium closeup

(@) Jn classical narration, style typically encourages the spectator fo construc “(he chest-up framing); the angk will be straight-on, at shoulder or chin level.

‘aco! 1: ace ofthe fabula action. “The framing is less ikely to be an extreme long-shot oc an extreme closeup, a

thigh or low angle. And a bird’ eye view ora view from straight below are very

improbable and would require compositional or generic motivation (eg, as an

‘optical point of view or 25 2 view of a dance ensemble in a musical)

Most explicitly codified into nies is the system of continuity

diferent purposes). Only classical narration favors 2 style which strives foc

Cimost denotative clarity from moment to moment. Each scones temporal

relation to its predecessor will be signaled early and unequivocally (by inert,

28 David Bordwell

i i space, and the

“The reliance upon an axis of ection orients the spectator to the space,

subsequent cutting, presents clear paradigmatic choices among different kinds

‘of “matches” That these are weighted probablistically is shown by the fact that

most Hlllywoed-ccenes_bepin-with-esabliching shots_brcak the space into

closer views linked by eyeline-matches and/or shot/rewnrsc shor and seni to

ote Sr acquis doe see to he ccocenied. ‘Playing an entire scene without

fan establishing shot is unlikely but permissible (specially if stock or location

forage or special effects are employed); mismatched screen direction and in-

consistently angled oyelines are les likely; percepiible jump cuts and unoioti-

vated cutaways are flatly forbidden. This paradigmatic aspect makes the classical

sc focal “ls nna formula os edipe but a historically constramed

set of more or less likely options *”

These three factors go some way toward explaining why the classical Hol-

Iywood style passes ‘eladvely unnoticed. Each film will eoombice familia

devices within fairly predicable paterns and according to the demands of the

syurhet. The spectator will almost never be at a loss to grasp a stylistic feature

because s/he is oriented in time and space and because stylistic figures will be

ble in the light of a paradigm.

RS oe com te ron of oye ad sj we can say that de

individual film is characterized by its obedience to a set of extrinsic normas which

gover both syuzhet construction and stylistic patterning, The classical cinema

does not entourage the film to es ee and

syazhet seldom enjoy prominence. A. film’s principal innov: ;

ral ofthe bula-te. “new stories” OF course, syuchet devices and stliste

features have changed over Gime, But the findamental principles of syuzhet

construction (preeminence of causality, goal-oriented protagonist, deadlines

etc) have remained in force since 1917. The stability and uniformity of Holly-

wood narration is indeed one reason to call it classical at east insofar as classicism

in any artis traditionally characterized by obedience to extrinsic norms

“The Logic of Classical Spectatorship

“The stability of syazhet processes and stylistic configurations should not make Sag

recat daniel spectator as passive material for a totalizing machine. Th Ge

‘eg baal and brlar The Hollywood fabula isthe produc of erie of

icular schemata, hypotheses, and inferences.

Pee pe spectator comes to classical film very well prepared. The rough shape 3

of syuzhet and fabula s ikely to conform to the canonic story of an individuals

goaboriented, causally determined activity. The spectator knows the most likey

stylistic figures and functions. The spectator has internalized the scenic noms

Classical Hollywood Cinema 29

of exposition, development of old causal line, and so forth. The viewer also

Jnows the pertinent ways to motivate what is presented. “Realistic” motivation,

in this mode, consists of making connections recognized as plausible by common,

opinion. (‘A man like this would naturally. . ") Compositional motivation

consists of picking out the important links of cause to effect. The most important

forms of transtextual motivation are recognizing the recurrence of a star’

persona from film to film and recognizing. generic conventions. Generic moti-

vation, as we have seen, hasa particularly trong effect on narrational procedures,

Finally, artstic motivation—taking an element as being present for its own

sako—is not unknown in the classical film. A moment of spectacle or technical

virtuosity, a thrown-in mnsical number or comic interlude: the Hollywood

cinema intermittently welcomes the possibility of sheer self-absorption. Such

‘omen ay be highly reflexive, “baring the device” of the narration’ own

‘Work, a5 when in Angels Over Broadway a destitute playwright reflects, “Our

present plot problem is money”

On the basis'of such schemata the viewer projects hypotheses. Hypotheses

tend to be probable (validated at several points), sharply excsive (rendered as

cither/or alternatives), and aimed at suspense (positing a fature outcome). In

Phil Rosen Roaring Timber (1937), a landowner enters a saloon in which our

hero is siting. The owner is looking for a tough foreman. Hypothesis: he will

ask the hero to take the joh. This hypothesis is probable, future-oriented, and

exclusive (either the man will ask our hero or he wort). The viewer is helped

in ffaming such hypotheses by several processes. Repetition reaffirms the data

‘on which hypotheses should be grounded. “State every important fact three

times” suggests scenarist Frances Marion, “for the play is lost ifthe audience

fais to understand the premises on which itis based.”® The exposition of past

fabula action will characteristcally be placed within the carly scenes of the

syuahet, thus supplying a firm basis for our hypothesis-forming. Except in a

mystery film, the exposition neither sounds waming signals nor actively mis

Jeads us, the primacy effec is given fll sway. Characters will be introduced in

typical behavior, while the star system reaffirms first impressions. (“The moment

you see Walter Pidgeon in 2 film you know he could not do a mean or petty

thing”)® The device of the deadline asks the viewer to construct forward-aiming,

all-orsnothing causal hypotheses: either the protagonist will achieve the goal in

time or s/he will not. And if information is unobtrusively “planted” early on,

|hter hypotheses will become more probable by taking “insignificant” foreshad-

‘owing material for granted.

‘This process holds atthe stylistic evel as well. The spectator constructs fabula

time and space according to schemata, cues, and hypothesis-framing. Holly-

‘wood! extrinsic norms, wit their fixed devices and paradigmatic organization,

supply the viewer with firm expectations that can be measured against the

‘concrete cues emitted by the film. In making sense of a scene's space, the

spectator need not mentally replicate every detail of the space but need only

\

Glaszal Hollywood Cinema 34

Implications and Avenues \

30 David Bordwell

constrict a rough relational map of the principal dramatic factors. Thus 2 “cheat

Cae is easly ignored because the spectators cognitive processes rank cues by

their pertinence to constructing the ongoing causal chain ofthe fbula, and on

this scale, the changes in speaker, camera position, and facil expression are

more notewortby than say, a slight shift in hand positions The same goes for

temporal mismatches.

"What is rare in the classical film, then, is Henry James’ “crooked corridor?

the use of narration to make us jump to invalid conclusions. The avoidance of

Gisorientation we saw at work in classical style holds good more broadly a

Swell, Future-oriented “suspense” hypotheses are more important than past

Gented “cutiosity” ones, and surprise is less important than either. In Roaring

“Timbo; imagine ifthe landowner bad entered the bar seeking a tough foreman,

offered the job to our hero, and he had replied in a fashion that showed he wes

ot tough, Indeed, one palrpose of foreshadowing and repetition is exactly to

“roid surprises later on. Of course if all hypotheses were steadily and imme-

‘Gately confirmed, the viewer would quickly lose interest. Several factors inter

‘ene to complicate the process. Most generally, schemata are by definition

bstract prototypes structures, and procedures, and these never specify all the

properties of the text. Many long-range hypotheses must avait confirmation

Retardation devices, being unpredictable to a great degree, can introduce objects

of immediate attention a5 well as delay satisfaction of overall expectation. The

primacy effect can be countered by what psychologists call a “reamcy effec”

Pinch qualifies and peiliys even appoare to negate on first impression of 2

tharacter or situation. Furthermore, the structure of the Hollywood scene, which

Simost invariably ends with an unresolved issue, insures that an event-centered

hnypothess carries interest over to the next sequence. Finally we should ne

tnvlerestimate the role of rapid dhythm in the classical film; more than_ooe

By virtue of its centrality within intemational film commerce, Hollywood

stylistic or syuzhet processes. Broadly speaking, we could periodize classical

Hollywood narration on thice levels. With respect to devices, we could trace

changes within classical narrational paradigms, accoeding to what options come

% ino favor at cena prods Here we should look not only for innovations but

normalization, patterns of majosty or custo ce.

E_ seenes by dissolves is possible but rare in the Stent cinema, yet ‘se Bel

.Jransition between 1929 and the late 1950s. On the dimension of narrational

sessed the pend tp more the construcuon of ory acon aba Ula ews we could sudy the zines dat consutesaszative causal

Bae a essence sno Geto selector es bord. is eek of ad space, Spt coniny within a ene cn be ached byl ting from

Sika narration to solicit strongly probable and exclusive hypotheses and then several functionally equivalere techniques, but such continu

Confirm them while still maintaining variety inthe concrete working out of the He et pee at en

: this postulate can be traced across the history of cinema. We could also study

Buctuations ofthe mote abstract narrational propertis over time. For instance,

ration in the 1920-1923 American silent cinema tends to be somewhat more

conscious than inthe later 19205, chiefly because ofa greater use of expository

es in the earlier period. Similarly, an insistently overt suppressiveness

: oe many El aoa wih he groping Enon fn Ln

at the manifold possibilities; we await a thorough hist.

scl storytelling and styl Ser

‘we might finally ask, does all this leave two important critical issues:

hip and ideology? In cis space, only sketchy answers can be suggested.

lent that. an auteur’s work can be identified by i

iciples and_patterns. cock and Fuller’ films are more

than, say, those of Hawks and Preminger. Moreover, we can associate

Moreover, we can associate _

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Burton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsDocumento20 pagineBurton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Trust and Civil Society (2000) - Fran Tonkiss, Andrew Passey, Natalie Fenton, Leslie C. Hems (Eds.)Documento203 pagineTrust and Civil Society (2000) - Fran Tonkiss, Andrew Passey, Natalie Fenton, Leslie C. Hems (Eds.)AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Geo6 CH23Documento36 pagineGeo6 CH23AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Murtagh 2015 Adaptive Utilitarianism, Social Enterprises and UrbanDocumento15 pagineMurtagh 2015 Adaptive Utilitarianism, Social Enterprises and UrbanAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- San Juan Cafferty 1979 Social Work Roles in Assessing Urban DevelopmentDocumento8 pagineSan Juan Cafferty 1979 Social Work Roles in Assessing Urban DevelopmentAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Moulaert-VandenBroeck Social Innovation and Territorial DevelopmentDocumento4 pagineMoulaert-VandenBroeck Social Innovation and Territorial DevelopmentAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Cohesion Policy Support For Local Development - Best Practices and Future Policy OptionsDocumento93 pagineCohesion Policy Support For Local Development - Best Practices and Future Policy OptionsAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Bottom Up Econ Dev and StateDocumento18 pagineBottom Up Econ Dev and StateAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Community-Based Social Economy - Social Capital and Civic Participation in Social Entrepreneurship and Community DevelopmentDocumento13 pagineCommunity-Based Social Economy - Social Capital and Civic Participation in Social Entrepreneurship and Community DevelopmentAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Culture and Local Development - Maximising The Impact (OECD, 2019)Documento100 pagineCulture and Local Development - Maximising The Impact (OECD, 2019)AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Guercio - Sustainability and Economic DegrowthDocumento3 pagineGuercio - Sustainability and Economic DegrowthAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Atlas of Emotion Capitulo 2 CompletoDocumento21 pagineAtlas of Emotion Capitulo 2 CompletoJoanaFelipecuryNessuna valutazione finora

- COE-Bank Part - 1-Inequality-Introduction - Lowres (2018)Documento36 pagineCOE-Bank Part - 1-Inequality-Introduction - Lowres (2018)AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- COE Bank Part - 2-Inequality-Education - Lowres (2018)Documento52 pagineCOE Bank Part - 2-Inequality-Education - Lowres (2018)AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Boulle e TreatiseDocumento36 pagineBoulle e TreatiseAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- COE-Bank Part - 3-Inequality-Housing (2018)Documento68 pagineCOE-Bank Part - 3-Inequality-Housing (2018)AthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- ArchitekturtheorieHilber - Eu Hilberseimer 100dpiDocumento38 pagineArchitekturtheorieHilber - Eu Hilberseimer 100dpiRamona DeaconuNessuna valutazione finora

- Boulle e TreatiseDocumento36 pagineBoulle e TreatiseAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- Le Corbusier The City Without Streets PDFDocumento13 pagineLe Corbusier The City Without Streets PDFKapil AroraNessuna valutazione finora

- LandscapeDocumento54 pagineLandscaperuanamariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Copenhagen Vol 2Documento27 pagineCopenhagen Vol 2AthenaMor100% (1)

- The Architecture of Movement - Patric SchumacherDocumento7 pagineThe Architecture of Movement - Patric SchumacherAthenaMorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Result of Delhi University Entrance Test (DUET) - 2019 University of DelhiDocumento10 pagineResult of Delhi University Entrance Test (DUET) - 2019 University of Delhiparveen790Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sirpy DiscographyDocumento6 pagineSirpy DiscographyLambo RiDDicKNessuna valutazione finora

- Us Documentary in WWIIDocumento13 pagineUs Documentary in WWIIRUBEN RODRIGUEZNessuna valutazione finora

- Covering Letter APGLI ProposalsDocumento2 pagineCovering Letter APGLI ProposalsADONI GOVT POLYTECHNICNessuna valutazione finora

- In Search of Dracula - The History of Dra - Raymond T. McNally PDFDocumento228 pagineIn Search of Dracula - The History of Dra - Raymond T. McNally PDFSoylent Green100% (12)

- LrisDocumento2 pagineLrisjeevithaNessuna valutazione finora

- E.W. Korngold - The Sea Hawk - SuiteDocumento32 pagineE.W. Korngold - The Sea Hawk - Suitendrube780% (5)

- AnastasiaDocumento4 pagineAnastasiaGénesis Mariana MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Kisi - Kisi Ujian Praktik Kelas 6 - 2023Documento1 paginaKisi - Kisi Ujian Praktik Kelas 6 - 2023sarkonahNessuna valutazione finora

- Mitv v9.2.5Documento50 pagineMitv v9.2.5Atzroulnizam AbuNessuna valutazione finora

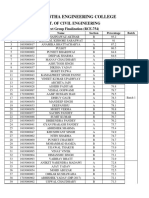

- Inderprastha Engineering College: Dept. of Civil EngineeringDocumento3 pagineInderprastha Engineering College: Dept. of Civil Engineeringsatyamsaxena2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Barney's Sense-Sational Day (All Versions) - Barney&Friends Wiki - FandomDocumento30 pagineBarney's Sense-Sational Day (All Versions) - Barney&Friends Wiki - FandomchefchadsmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Tamilnadu DoctorsDocumento41 pagineTamilnadu DoctorsCHANDRAN MAHA50% (2)

- ITL, Media, Clinical, Refugee, Insurance Law - Viva ScheduleDocumento7 pagineITL, Media, Clinical, Refugee, Insurance Law - Viva SchedulesriprasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Subiectul I Read The Text Below. For Question 1 - 10, Choose The Answer (A, B, C or D) Which You Think Fits Best According To The TextDocumento3 pagineSubiectul I Read The Text Below. For Question 1 - 10, Choose The Answer (A, B, C or D) Which You Think Fits Best According To The TextMisha MishaNessuna valutazione finora

- 01/2021 Uttar Pradesh Secondary Education Service Selection Board: TGT - CommerceDocumento9 pagine01/2021 Uttar Pradesh Secondary Education Service Selection Board: TGT - CommerceShekhar DixitNessuna valutazione finora

- Note: Contact Details of Faculty Members Are Mentioned After Section C Name List of Students. Jaipur Engineering College & Research Centre, JaipurDocumento4 pagineNote: Contact Details of Faculty Members Are Mentioned After Section C Name List of Students. Jaipur Engineering College & Research Centre, JaipurshreyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sybil DanningDocumento6 pagineSybil DanningMIDNITECAMPZNessuna valutazione finora

- Greek Cinema Volume 3 Documentaries and Short Movies 032212Documento502 pagineGreek Cinema Volume 3 Documentaries and Short Movies 032212aisy24100% (1)

- Buildings A A A TheDocumento1 paginaBuildings A A A TheThảo Nguyễn ThanhNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Planning Mar'2020Documento16 pagineBusiness Planning Mar'2020Narasimman NarayananNessuna valutazione finora

- Watch The Marvel Movies in OrderDocumento27 pagineWatch The Marvel Movies in OrderJustin Work SimplexNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - 05 - 2022 - Result of FT (OYM&CF) - 2223 - T01Documento4 pagine08 - 05 - 2022 - Result of FT (OYM&CF) - 2223 - T01Løne WølfNessuna valutazione finora

- Grace AssessmentDocumento39 pagineGrace AssessmentJoshuva YuviNessuna valutazione finora

- Ac Ac0418 PDFDocumento140 pagineAc Ac0418 PDFFilip PeruzovicNessuna valutazione finora

- MksRcdCndts-NDAII 2020 130721Documento26 pagineMksRcdCndts-NDAII 2020 130721Animesh RathoreNessuna valutazione finora

- 4Th Ordinary Election To MPTC / ZPTC - 2014: Form X (B) ZPTCDocumento3 pagine4Th Ordinary Election To MPTC / ZPTC - 2014: Form X (B) ZPTCShane RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Media-Based Art - Photography Film and AnimationDocumento19 pagineMedia-Based Art - Photography Film and AnimationBaby GeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lata Mangeshkar: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocumento11 pagineLata Mangeshkar: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDoshant GharteNessuna valutazione finora

- LifeMembersList PujaDatesDocumento264 pagineLifeMembersList PujaDatesEsha SharmaNessuna valutazione finora