Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cassone 618 Ai Reflection Paper

Caricato da

api-2306788760 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

38 visualizzazioni5 pagineTitolo originale

cassone 618 ai reflection paper

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

38 visualizzazioni5 pagineCassone 618 Ai Reflection Paper

Caricato da

api-230678876Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 5

Appreciative Inquiry Reection Paper

Marco Cassone MSOD 618 Dr Julie Chesley

OPENING REFLECTION

Prior to Costa Rica, my learning group, entertained a lively discussion on if and how AI differs

from other interventions. Is it yet another tool we may add to our trusty OD toolkit alongside so

many others? And if so, does one presume a particular kind of client, context, circumstance, or

OD diagnosis that clearly points to AI above other interventions? The telltale sign of any good

dialogue is coming away with more questions than answers, which was certainly the case here.

THE TWO LEVELS OF AI

Appreciative Inquiry lives on two levels that can seem conated to me. In the context of our

study, AI has occurred as the next stop on the MSOD buffet line of interventions to sample and

ingest, but limiting AI like this doesnt feel quite right. AI is indeed a tool with a specic and

developed protocol as an intervention; more importantly, however, it is also a perspective that

lives above any particular application. What Ive learned from the MSOD program is the inherent

complexity of OD itselfthat is, the numerous co-existing ways of slicing and dicing reality

depending on the questions asked and intended focus of attention. In this way, the world can be

divided into problem-centered and strengths-based approaches, and as we gleaned from

Appreciative Living, these can be applied at any level of system, from individuals to

organizations. Independent of how a particular AI intervention might be applied, one can nd

great reward in bringing an appreciative outlook to most situations and relationships in life.

THE ADDICTIVE NATURE OF PROBLEMS

So I asked myself why wouldnt everyone espouse a strengths-based approach all the time? A

fair enough question. The answer is the same answer as to why soap operas, reality TV, and

pop lyrics exist: ego fodder. Self-assigned as our silent, protective sentinel, the human ego is

always scanning the horizon for the next potential threat, and problems are too deliciously

addictive not to pay attention to. After all, they not only validate our OD toolkits, they validate us,

the problem solvers! There is an addictive, cyclical nature to constant re ghting, which can

make it difcult for both OD consultants and those we serve to discern when a strengths-based

approach will truly serve and when it might simply occur irrelevant and detached from reality.

TURNING TO AI IN COSTA RICA

My consulting team in Costa Rica consisted of my co-leader, Patrice Pederson, and fellow

cohort members, Melissa Cruz and David Loebsack. We were paired with the CRUSA

Foundation, a private, independent, non-political, and non-prot Costa Rican foundation. This

was not an easy assignment, to be sure, although I believe a strong outcome was achieved and

experienced by the limited participants involved.

THE COMPLEXITY OF CRUSA

Our primary contact at CRUSA was the Program Director, MCa change agent herself, and

given the limitations of her subordinate role, a secret change agent at that. She is a driven,

passionate leader in her own right, and her title perhaps belies her vision and capacity to

develop her organization. From the start, MC openly criticized the CRUSA Board of Directors as

calcied in their conservative and fear-based approach to the nearly $90M they control.

My personal/professional impression is that MC may not have understood the aim of the AI

workshop offered through our Pepperdine practicum. Pressure of an impending board meeting

introduced an immediate and unshakeable presenting problem; as such, MC had a xed idea of

what useful and viable solutions for her could look like. This tunnel vision confounded our

student team from achieving the goal of co-facilitating an AI intervention for CRUSA. All of our

discussion with MC centered around how to get the BoD to change, yet she had never intended

to get them in the room to work with. Based on her behavior and choices, its arguable whether

MC entertained AI as a possibility; she had neither the capacity nor the authority to allocate

precious board meeting time to something as elusive as appreciative inquiry. In this way, what

transpired was likely far from the intended practicum design of co-presenting AI to as many

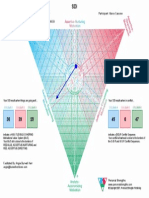

available from the host system as possible, a goal depicted in the expanded, yellow-now-green

inner circle on the far right below:

Day 2

Intended host

org dept (w/ initial

presenting problem)

as target to experience

co-facilitated day 2

AI intervention

+ =

Day 1

org sub-group

learning about

AI w/ MSOD

students

Goal: host

org dept (w/ initial

presenting problem)

experiences benet of

AI as learned tool &

new paradigm for

problem solving

in future

AN APPRECIATIVE REVIEW OF WHAT TRANSPIRED

A little context. Her strong background working with nonprots gave Patrice both an advantage

and disadvantage in listening to MC share her presenting problem with our team on day 1. The

circumstance seemed the perfect opportunity to take advantage of Patrices wealth of

professional knowledge; the more MC dove into her trials and tribulations with the board, the

more Patrice showed sincere empathy and a desire to jump into potential solutions. This was a

valuable lesson for me to observe how easy it is to unconsciously let strengths and professional

past collude with a client, especially in initial stages when building rapport.

At some point in our never-ending intake, I interrupted to refocus the group on the task at hand,

which was designing our co-facilitated AI presentation the following day. The slightly dismissive

response from MC began to paint the picture that her intention all along had been to harvest

grad school business student ideas towards her immediate problem; exploring the benets of AI

to improve her relationship to the board may not have been a real consideration.

WHAT SENSE DO I MAKE HERE

The quick label I give this circumstance is lack of clarity in initial contracting, but this may be an

oversimplication. Western business culture steeps us in problem solving; it is fundamentally

ingrained in our worldview, and becoming aware of it is like asking a goldsh to be aware of the

water it swims in. So I certainly cant fault MC for either her addictive problem-centered focus

nor her resistance to any discussion outside of immediate solution. My takeaway here is this will

likely be a common experience I must learn to navigate in future OD engagements, that

problem-solving will often trump client openness to exploring different paradigms or new ways of

looking at the problems they have to solve. This means I must develop the skill of truly hearing

client pain points while simultaneously building client openness to new alternatives.

WHAT DID WE DO

Im proud to say that our team ultimately succeeded in trusting the processanother valuable

lesson for me. Despite the hours of late night deliberation on how and whether to use our clever

brain power to help MC solve her issues, our nal course of action for Day 2 was quite simple:

Take back control of the dialogue in order to focus on our list of appreciative questions,

Feed back to MC the themes, connections, and inconsistencies we heard in her sharing,

Finish with questions allowing MC to have her own insights and draw her own conclusions.

THE RESULT

In the end, MC came away with a transformational shift in her point of view. From her

progressive perspective, CRUSAs board of directors only cared about protecting its image and

assets; growth in the organization occurred at a glacial pace at best. From this context, the only

possibility she saw for enacting change and receiving project funding was to cater to the boards

fear and ignorance, covertly couching her own organizational change initiatives within bullet-

proof proposals the board couldnt say no to. She had been insulating the board from anything

but rosy reports, inadvertently robbing the board of any pain or reward point that might be

impetus for reection and growth. The ah-ha we helped her see is that she could grow the

boards intrinsic desire to evolve by growing an organizational interest in evaluating the

successesand failuresof CRUSA funded projects. Her covert tactics in capacity building

would be much easier if the board members themselves could be enrolled in improving their

effectiveness and valuing their excellence.

TOUCHING BACK ON MY PRACTICE POINT OF VIEW

In my learning journal summary, I shared about my new fascination with structure and the

emergent, especially as elements that affect our learning group dynamics. Id like to step away

from CRUSA momentarily to explore how these elements might also relate to large scale

interventions. Im coming to appreciate structure as a necessary container for the emergent.

Heres my analogy: ooding water always ows along the easiest path available. Without a

pathway to follow, water ow is unpredictable, but over a river bed or canyon, it is guided by the

available structure. Consider what can replace water to build on this metaphor: energy,

attention, thinking, inspiration, dialogue, learning, action, and so much of what we study in the

behavioral sciences. Nothing guides an ensuing dialogue better, for example, than the structure

of good initial questions. (Note to self: Remember to apply this to my thesis!) This is

profoundly important when it comes to designing experiential learning and OD interventions

large and small: it is structure that allows energy to be gathered, directed, bottled, and diffused.

HOW THIS AFFECTS MY PERSPECTIVE ON CHANGE MANAGEMENT

Considering our recent AI practicum, Im now starting to see the transformational potential of

getting the whole system in the room to create a shared vision of the future. After all, humans

are social creatures, and learning itself is a highly social process. In this way, perhaps it can be

said that one of the strongest forms of enrollment, change readiness, and conviction on a

personal level comes from shared the ah-has experienced on a collective level. It is inside of

relationships and dialogue that we make sense of the world, which is always a uid interplay

between past, present, and future that is continually redened through human interaction. In this

way, the term change management occurs like a top-down command-and-control charade that

totally misses the point. Of course 70% of all change management initiatives fail if management

pushes them through as if organizations are machines composed of homogenous, non-thinking

autobots. People are complex, teams and groups are more complex, organizations and trans-

org systems are unbelievably complex. In each case, there are as many diverse and

incongruent mental models about reality as there are people in a given system.

WHY THIS IS IMPORTANT TO ME

One thing Im passionate about in my Practice Point of View is helping organizations harness

and maximize care. I see care as a number one limited resource worth protecting. Lack of care

is the hidden cancer that eats away at organizational wellbeing. When leaders assume

employees are paid to buy into a depersonalized, homogenous, and centrally spoon-fed way of

dealing with change, they are inadvertently asking people to minimize their own sense making

of transition and preventing them from nding their own reason to care about it. In this way, OD

practitioners must create interventions that provide the structural containers in which stories,

perspectives, visions, conicting motivations, misaligned understandings, etc. may emerge and

coalesce into shared ah-has. Change management should not avoid the complexity of

independent, co-existing mental models as much as nd ways to absorb complexity and grow

from it. By having every voice in the room engaged in dialogue and feeling heard, the shared

ah-has become the foundation that allows individuals to glean their own insights, make their

own sense of change, rediscover their care, and ultimately choose their own personally-

meaningful resolve to move ahead; without which most unsuccessful change initiatives simply

add to the 70% statistic of failure.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Psych ReviewerDocumento4 paginePsych ReviewerAudrey AngNessuna valutazione finora

- Aviso de Tormenta Spanish Edition by Billy Graham 1602554390 PDFDocumento5 pagineAviso de Tormenta Spanish Edition by Billy Graham 1602554390 PDFAntonio MoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Aashto T 99 (Method)Documento4 pagineAashto T 99 (Method)이동욱100% (1)

- Six Degree AlchemyDocumento14 pagineSix Degree Alchemyapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fab 4 I D e A ObservationsDocumento1 paginaFab 4 I D e A Observationsapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Transformative Listening Thesis 7-24-14Documento101 pagineCassone Transformative Listening Thesis 7-24-14api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Msod620 Blue Team Paper FinalDocumento17 pagineMsod620 Blue Team Paper Finalapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Learning Journal Summary March 2014Documento3 pagineCassone Learning Journal Summary March 2014api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Post-American World For AlchemyDocumento9 paginePost-American World For Alchemyapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Xcassone Reflection Paper Msod 620Documento5 pagineXcassone Reflection Paper Msod 620api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Palleschi RecommendationDocumento1 paginaPalleschi Recommendationapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- MGT Reset 10 TakeawaysDocumento14 pagineMGT Reset 10 Takeawaysapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone 616 Individual Learning JournalDocumento5 pagineCassone 616 Individual Learning Journalapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sdi Interpretive GuideDocumento7 pagineSdi Interpretive Guideapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marcos PDC Oct 2013Documento1 paginaMarcos PDC Oct 2013api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Book Summary Notes Post American World FinalDocumento4 pagineBook Summary Notes Post American World Finalapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ocai Omicron Prime Culture Report Ver 6Documento9 pagineOcai Omicron Prime Culture Report Ver 6api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marco Cassone 60b29a1c 5f80 4f24 Ad08 6344215913a7Documento1 paginaMarco Cassone 60b29a1c 5f80 4f24 Ad08 6344215913a7api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marcos Shortened Profile For AlchemyDocumento11 pagineMarcos Shortened Profile For Alchemyapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone M Admissions EssayDocumento1 paginaCassone M Admissions Essayapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Complexity in Di InitiativesDocumento9 pagineCassone Complexity in Di Initiativesapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ai Alchemy SlidedeckDocumento25 pagineAi Alchemy Slidedeckapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marco Final Exam Study Prep2Documento26 pagineMarco Final Exam Study Prep2api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complexity Alchemy PresentationDocumento42 pagineComplexity Alchemy Presentationapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Learning Journal SummaryDocumento2 pagineCassone Learning Journal Summaryapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- SwanncassonepatagoniapairpaperDocumento11 pagineSwanncassonepatagoniapairpaperapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Msod620 Cango Pres FinalDocumento85 pagineMsod620 Cango Pres Finalapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Reflection Paper Msod 620Documento5 pagineCassone Reflection Paper Msod 620api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Closing Session PosterDocumento1 paginaClosing Session Posterapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone Ppov Paper 621Documento4 pagineCassone Ppov Paper 621api-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cassone 616 Post-Session Emlyon Evaluation PaperDocumento6 pagineCassone 616 Post-Session Emlyon Evaluation Paperapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ai in Practice Imagining A Bright Future ChesleyDocumento47 pagineAi in Practice Imagining A Bright Future Chesleyapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity & Inclusion DiscussionDocumento9 pagineDiversity & Inclusion Discussionapi-230678876Nessuna valutazione finora

- 7. Sách 35 Đề Minh Họa 2020 - GV Trang AnhDocumento771 pagine7. Sách 35 Đề Minh Họa 2020 - GV Trang AnhNhi CậnNessuna valutazione finora

- Critiques of Mixed Methods Research StudiesDocumento18 pagineCritiques of Mixed Methods Research Studiesmysales100% (1)

- FQ2 LabDocumento10 pagineFQ2 Labtomiwa iluromiNessuna valutazione finora

- ADMINLAW1Documento67 pagineADMINLAW1FeEdithOronicoNessuna valutazione finora

- The SophistsDocumento16 pagineThe SophistsWella Wella Wella100% (1)

- Ich GuidelinesDocumento5 pagineIch GuidelinesdrdeeptisharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashok B Lall - 1991 - Climate and Housing Form-A Case Study of New Delhi PDFDocumento13 pagineAshok B Lall - 1991 - Climate and Housing Form-A Case Study of New Delhi PDFAkanksha SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- 495 TextDocumento315 pagine495 TextSaiful LahidjunNessuna valutazione finora

- Idsl 830 Transformative Change Capstone ProjectDocumento33 pagineIdsl 830 Transformative Change Capstone Projectapi-282118034Nessuna valutazione finora

- Zhejiang TelecomDocumento4 pagineZhejiang TelecomShariffah Rekha Syed SalimNessuna valutazione finora

- Training: A Project Report ON & Development Process at Dabur India LimitedDocumento83 pagineTraining: A Project Report ON & Development Process at Dabur India LimitedVARUN COMPUTERSNessuna valutazione finora

- Rename Quick Access FolderDocumento13 pagineRename Quick Access FolderSango HanNessuna valutazione finora

- Fehling Solution "B" MSDS: Section 1: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationDocumento6 pagineFehling Solution "B" MSDS: Section 1: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationAnnisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dmitri Sorokin - Introduction To The Classical Theory of Higher SpinsDocumento33 pagineDmitri Sorokin - Introduction To The Classical Theory of Higher SpinsKlim00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Nirav Vyas Numerical Method 4 PDFDocumento156 pagineDr. Nirav Vyas Numerical Method 4 PDFAshoka Vanjare100% (1)

- Knowledge Intensive Business Services (KIBS) : Don Scott-Kemmis July 2006Documento8 pagineKnowledge Intensive Business Services (KIBS) : Don Scott-Kemmis July 2006KALAWANessuna valutazione finora

- Tugas Bahasa InggrisDocumento10 pagineTugas Bahasa InggrisFirdanNessuna valutazione finora

- MATLab Manual PDFDocumento40 pagineMATLab Manual PDFAkhil C.O.Nessuna valutazione finora

- 50 Affirmations For A Fertile Mind, Heart & SoulDocumento104 pagine50 Affirmations For A Fertile Mind, Heart & SoulKarishma SethNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderDocumento12 pagineDiagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderAnonymous 0uCHZz72vwNessuna valutazione finora

- To Fur or Not To FurDocumento21 pagineTo Fur or Not To FurClaudia CovatariuNessuna valutazione finora

- Venue and Timetabling Details Form: Simmonsralph@yahoo - Co.inDocumento3 pagineVenue and Timetabling Details Form: Simmonsralph@yahoo - Co.inCentre Exam Manager VoiceNessuna valutazione finora

- BPP Competency Assessment Summary ResultsDocumento1 paginaBPP Competency Assessment Summary Resultslina angeloNessuna valutazione finora

- The Four Faces of MercuryDocumento6 pagineThe Four Faces of MercuryAndré Luiz SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- African Handbook-TextDocumento164 pagineAfrican Handbook-TextThe_Castle_Of_Letter100% (1)

- Converting .Mp4 Movies With VLCDocumento5 pagineConverting .Mp4 Movies With VLCrazvan_nNessuna valutazione finora

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs4349.001 05f Taught by Ovidiu Daescu (Daescu)Documento4 pagineUT Dallas Syllabus For cs4349.001 05f Taught by Ovidiu Daescu (Daescu)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNessuna valutazione finora