Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ed 6630 Inquiry Project Paper

Caricato da

api-2502164260 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

101 visualizzazioni21 pagineTitolo originale

ed 6630 inquiry project paper

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

101 visualizzazioni21 pagineEd 6630 Inquiry Project Paper

Caricato da

api-250216426Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOCX, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 21

Running head: COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 1

Cooperative Learning in Mathematics Education

by

Ashley Wood

200206357

A paper submitted to the Faculty of Education

in conformity with the requirements for

Ed 6630

Memorial University of Newfoundland

St. Johns, NL, Canada

June 22, 2014

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 2

Cooperative Learning in Mathematics Education

Encouraging students to develop high levels of learning in mathematics is a top priority

for many educators of any grade level. Teachers strive to create a classroom environment where

students are engaged, attentive, and actively involved in the learning process by incorporating

new resources and different pedagogical practices. Unfortunately, many of our current students

are progressing through the educational system with a lack of basic math skills and the

perception that mathematics is a subject contained only within the walls of a classroom. This

perspective, coupled with negative student attitudes and low motivation levels towards

mathematics learning may leave many educators feeling less confident in their teaching abilities,

causing them to rely on traditional, teacher-centered lessons which focus on explicitly taught

rules and strategies. Understanding new instructional approaches which can increase student

achievement and promote high levels of motivation may help increase positive attitudes towards

learning new mathematical concepts, which may in turn help better prepare our students for the

real world.

The following paper seeks to discover more about cooperative learning and how this

instructional practice can be utilized to help increase motivation and student achievement in

mathematics. In doing so, current achievement trends among the students in our province will be

analyzed along with the need to move away from a heavy reliance on traditional math lessons.

Defining cooperative learning, identifying the benefits which come from this collaborative

teaching method, and discussing several cooperative learning strategies will be examined in

relation to the effect they have on student performance and motivation. Lastly, identifying

challenges which can come from the implementation of cooperative learning along with various

recommendations and teacher implications are discussed in a manner which encourages all

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 3

educators to try this positive pedagogical approach. This research will show that cooperative

learning is a valuable teaching tool which encourages knowledge acquisition and a love of

mathematics learning among our students, making it an ideal strategy to incorporate into any

classroom.

Current Achievement Trends in Mathematics

As a grade six math teacher, I see many students enter into my classroom who lack

motivation or who have a very negative attitude towards mathematics. Whats even more

alarming is the fact that many of these students are also lacking basic mathematical skills, which

impedes their development of strong mental math and mathematical reasoning abilities. It can be

unnerving to learn that this seems to be a trend among the achievement levels of the grade six

students across our province. Analyzing the elementary mathematics provincial assessment data

indicates startling results. On the four process strands assessed during the 2008 mathematics

CRT (reasoning, communication, connections and representations, and problem solving) roughly

half of our students were achieving below a level 3 on the scoring rubric, where a level 3 would

indicate a good understanding (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2012). In 2009, a

startling 60% of our grade six students were not yet meeting the outcomes in the number

operations strand of our mathematics curriculum, and although there have been significant gains

over the last number of years, the most current data for 2012 indicates that only 54% of our

students are demonstrating a proficiency in number operations (Government of Newfoundland

and Labrador, 2012).

These results correlate with the Program for International Assessment (PISA) given to

Canadian students by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 4

2012. This assessment measures the performance of Canadas youth in mathematics, which was

given to 21 000 15 year old students across the country from 900 schools. The results of this

assessment indicated that Canada as a whole is performing quite well in mathematics, as only

nine of 65 countries in total outperformed our country (Brochu, Deussing, Houme, & Chuy,

2012). Closer inspection of the results however reveals that not all provinces fared in a similar

manner. Newfoundland and Labrador preformed below the Canadian average in all areas of the

paper-based mathematics component, and of the ten provinces which participated in the

assessment, Prince Edward Island was the only one which scored lower results than our

province. Unfortunately, our results may indicate a movement in mathematics achievement

which is slowly catching up with the rest of our country, as there is a clear trend showing a

decrease [among the] average score(s) in most provinces, as well as an increase in the number of

countries outperforming Canada (Brochu et al., 2012, p.31). These results prove to be alarming

for many educators, indicating a need to reflect on specific classroom practices that may help

explain and account for these deficiencies.

Moving Away from Traditional Modes of Learning

Why are so many of our students underperforming in mathematics during a time when

various forms of technology and other educational resources are readily available? The answer

may come in part from the type of instructional strategies educators avail of in order to teach

mathematical concepts and strategies. Traditional modes of mathematics instruction involve

direct teacher-centered lessons, in which the teacher stands at the board and transfers knowledge

to students through explicit instructions and endless examples. While this type of instructional

approach may have a place in the classroom, consistently teaching mathematics in this manner

may have some effect on the meaningful learning taking place. According to Schoenfeld (1988),

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 5

teachers can trivialize mathematics and deprive students of the opportunity to understand and

use what they have studied by presenting meaningless math examples which are presented and

solved out of context (p.147). Unfortunately, many of our more traditional practices present

mathematical concepts in this disjointed view, which may lead to a superficial understanding of

the subject.

Moving away from a heavy reliance on traditional pedagogical teaching approaches may

help our students succeed in becoming competent mathematics learners in and outside of the

classroom. This presents new challenges however, as many teachers enter into the profession

with contemporary beliefs about how they should teach, but when faced with typical classroom

constraints they tend to refer back to more traditional classroom practices (apkova, 2014).

Trying to find a balance between promoting deep levels of learning among students while

dealing with time and resource restrictions can be difficult, however it is necessary for the

promotion of mathematically competent learners, as students develop their understanding of

mathematics from their classroom experience with it (Schoenfeld, 1988). Educators need to

become comfortable with new teaching methods that encourage a deeper mathematical

understanding that can be transferred and used outside of the classroom, which is why

cooperative learning has gained popularity as a pedagogical practice that helps promote

knowledge acquisition through cooperation and collaboration.

Defining Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning can be traced back to its roots in Vygotskys social constructivism

theory. Vygotsky believed that social interaction and collaboration are integral components of

the learning process as students internalize information more effectively when they interact with

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 6

others, leading to deeper levels of understanding (Powell & Kalina, 2009). One aspect of the

social constructivist theory suggests that students will learn more effectively during their zone of

proximal development, which is a zone where comprehension occurs with the help of other

individuals. This help can come in the form of scaffolding, which is a type of assisted

instructional process that supports the zone of proximal development, allowing students to get to

the next level of understanding in the learning process (Powell & Kalina, 2009). Social

constructivism relies heavily on the idea that students learn best when we give them the

opportunity to discuss, interact, and collaborate with other learners. It is through this social

process that meaningful learning occurs as students create connections between what they

already know to the new concepts they become introduced to in class.

Taking the social constructivist theory into account, cooperative learning defines a type

of instructional practice used to enhance the understanding of students in the classroom. Simply

stated, cooperative learning occurs when students work together towards a common goal on

academic tasks (Nattiv, 1994; Hancock, 2004; Ifamuyiwa & Akinsola, 2008). In this student-

centered approach to learning, every individual is responsible for their own level of

comprehension as it is necessary for the groups success (Naseem & Bano, 2011). Group rewards

and individual accountability are an essential component of this learning process as it prevents

high achievers from dominating the work and forces students to take responsibility for their own

mastery of the material (Whicker, Nunnery, & Bol, 1997). In the mathematics classroom,

cooperative learning occurs when students interact and work together in a collaborative and

social manner on assigned mathematical tasks while the teacher monitors the groups and

intervenes only when it is necessary to improve the mathematical abilities of students (Tarim,

2009). In defining cooperative learning, it is important to note that not all group work completed

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 7

in the classroom can necessarily be labeled as being cooperative in the social constructivist

sense. A defining characteristic of cooperative learning implies that students are interacting in an

academic manner which promotes the learning of each other; simply sitting next to other peers

and participating in ongoing discussions dos not mean that cooperative learning is occurring

(Tarim, 2009).

Cooperative learning groups are generally heterogeneous in nature, which serves to help

the learning process as students use their unique background experiences and previous

knowledge to enhance the learning of the full group. In order for this interactive learning

approach to work, there are five essential elements which are discussed throughout the relevant

research which helps ensure these mixed-ability groups are being effective in facilitating their

own learning. Groups need to have positive interdependence among members, face to face

interactions, individual accountability, appropriate social skills, and group processing abilities

(Naseem & Bano, 2011; Hsiung, 2012). Learning will not occur as effectively if students are

placed together in groups without these interactive skills needed to promote the learning process.

Students need to learn to rely on each other when assistance is needed while groups are working.

The role of the teacher becomes very subdued in a cooperative learning environment after the

initial work of composing the groups and assigning the task has finished. In effective cooperative

learning environments, teachers become coaches, facilitators , and even spectators after the

lesson has been implemented, as teachers who set up a good cooperative lesson teach children

to teach themselves and each other (Naseem & Bano, 2011, p. 84). There is a shift in

dependency in a cooperative learning environment, students learn from each other instead of

directly from the teacher.

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 8

Benefits of Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning has many different benefits which makes it a worthwhile

instructional approach to implement in the mathematics classroom. One of the most valuable

benefits of cooperative learning is the level of motivation it instills in students working on

mathematical concepts. Research studies have shown that the implementation of cooperative

learning in the classroom motivates students to spend more time on academic tasks (Naseem &

Bano, 2011; Hsiung, 2012). It also increases motivation to learn, enhances students enjoyment

of school and classes, and has been linked as a contributing factor to the improvement in

attendance among students (Whicker, Nunnery, & Bol, 1997). Likewise, cooperative learning

motivates students to encourage one another to achieve success on group assignments, drives

students to help one another succeed, and motivates learners to interact with the academic task

and with each other in a positive manner (Ifamuyiwa & Akinsola, 2008). This increase in student

motivation can have a profound effect on classroom behaviours. Students who stop working or

shut down when encountering an unknown problem independently are motivated in a

cooperative learning group to persist in the problem solving to ensure the groups success. This

can help motivate students to stay on task longer than if they were working alone.

Another benefit of cooperative learning is the positive impact it can have on

mathematical achievement levels. Throughout the relevant research, studies have shown positive

mathematics achievement scores in cooperative learning classrooms, many indicating a

significant achievement increase when compared to experimental learning groups (Whicker,

Nunnery, & Bol, 1997). This positive relationship between cooperative learning and student

achievement is not limited to a specific age group either; the effects on academic achievement

through cooperative learning have been noted in studies conducted on preschool learners up to

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 9

high school students and even on post-secondary learning groups (Tarim, 2009; Whicker,

Nunnery, & Bol, 1997; Hancock, 2004). One of the most commonly referenced reasons that

explain this positive connection between cooperative learning and mathematics achievement is

the shift in dependency which occurs from the classroom teacher to other group members.

Students become responsible for teaching each other in cooperative learning environments,

which requires them to explain the information they understand on the new concepts introduced

in class. As suggested by Webb, Franks, De, Chan, Freund, Shein, and Melkonian (2009), when

explaining the material necessary for task completion, students participate in the opportunity to

reorganize and clarify material, identify misconceptions, fill in missing gaps in their own

understanding, internalize new knowledge, and develop new perspectives and understanding

(p.50). When students are required to discuss academic tasks they need to take in the new

information, relate it to their existing understandings, and then explain it in a manner which

helps other students understand the material. This can lead to a better understanding of the work

being presented.

Besides the positive influences cooperative learning has on motivation and achievement,

this interactive instructional strategy has several other benefits which come from its highly social

nature. Cooperative learning helps to nurture an inclusive classroom environment as it helps

strengthen relationships among students, increasing their acceptance of the differences which

occur among learners (Whicker, Nunnery, & Bol, 1997). When students are required to

collaborate and work together towards common goals they get the opportunity to interact with

students who they may have otherwise chosen not to socialize with. Increasing the interactions

occurring in the classroom helps students appreciate and see the value in differences which may

be present among learners. As suggested by Powell and Kalina (2009), to embrace diversity,

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 10

students must interact socially (p.245). As cooperative learning tasks are generally

heterogeneous in nature, students have the opportunity to complete work in a manner which

caters to their strengths and different learning styles. The adaptive nature of these tasks can be

opened up to all students including those who have special needs, which helps promote an

atmosphere of acceptance and appreciation in the classroom.

Additionally, there are many other indirect benefits of cooperative learning which helps

increase its value as a mathematical teaching method. Cooperative learning helps to promote

leadership among students as dependency on the teacher decreases. It also helps in the promotion

of important social skills such as sharing, cooperation, and teamwork (Naseem & Bano, 2011).

Regularly participating in cooperative learning tasks also has a positive effect on a students self-

esteem and confidence levels, increasing positive attitudes towards school while decreasing the

anxiety some students feel towards work completion in the classroom (Tarim, 2009). There are

also economic benefits to implementing cooperative learning in the classroom; allowing students

to work in groups permits a class to complete the same quality of work using less materials and

equipment than if students were required to complete the same work independently (Naseem &

Bano, 2011). These diverse benefits are products of a classroom where students are actively

working together to enhance each others learning. Although a teacher may implement a

cooperative learning activity for a specific reason, many unseen qualities emerge from positive

and productive student interactions.

Cooperative Learning Strategies

There are a variety of different ways cooperative learning can be used in the mathematics

classroom. One method, as described by Whicker, Nunnery, and Bol (1997), relies on group

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 11

rewards and individual accountability. The Student Teams-Achievement Divisions (STAD)

method encourages competition between groups while concurrently promoting cooperation

within groups. This approach involves awarding teams points based on the performance of

individual group members. This helps to ensure that all members learn and interact with the

concepts and strategies being learned. A teams score is based on its members continued

improvement on assessment tasks, and points are given based on the percentage of increase of a

students grade from one assessment piece to the next. This gives all students the opportunity to

contribute a maximum amount of points to their team. As reported by Majoka, Dad, and

Mahmood (2010) in their study of incorporating STAD as a learning strategy in the mathematics

classroom, students participated in a higher level of engagement resulting in higher mathematical

achievements using this approach when compared with students who received traditional

methods of instruction. This cooperative learning strategy can easily be integrated into the math

classroom on a regular basis using various forms of assessment as the basis for each cooperative

task. A teacher can give points to the teams whose group members continued to demonstrate an

improvement on pre-assessments, formative assessment tasks, and summative learning activities,

which can be developed from any area of the mathematics curriculum.

Another cooperative learning method which combines group goals with individual

accountability is called Team Assisted Individualization, or TAI for short. Tarim and Akdeniz

(2008) explain how this strategy works, starting with the introduction of a new concept or

strategy which is taught to the whole class by the teacher over the course of one or two periods.

Students are then given a task, in the form of a worksheet or a question set, to complete

individually within their groups. After each section of the task is completed, students compare

their answers with each other, and then cross-reference with a provided answer key. If all the

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 12

questions were answered correctly, students can move on to a different task. If any answers were

wrong, the student seeks help or clarification from group members, and if necessary, the teacher.

When a student has correctly completed a task, they can take a checkout which is a type of quiz

containing questions relating to the topic being studied. This is completed individually, and then

checked by group members. If 80% of the checkout was completed correctly, the student could

complete a final test individually. A score of less than 80% requires teacher assistance to help

clear up any misunderstandings about the material, and then another checkout quiz is

administered before being allowed to complete the final test. This cooperative learning method is

an appealing choice for the mathematics classroom for a number of different reasons. Not only

does the relevant research indicate a positive relationship between TAI and mathematics

achievement, teachers prefer this instructional strategy because it can easily be used in any strand

of the mathematics curriculum as it is an adaptable learning method thats easy to initiate and

maintain (Tarim & Akdeniz, 2008).

Student-Team Mastery Learning (STML) is yet another cooperative learning strategy

used by mathematics teachers. This method starts by students working cooperatively in small

groups on a task which is contingent on the collaboration of group members. Students are then

individually tested in a formative manner to determine strengths and weaknesses in their

learning. Supplemental activities are then given to groups based on the formative assessment

results, where it is expected that higher-achieving students will help other group members master

the given tasks (Mevarech, 1985). This learning strategy takes root from Blooms work on

mastery learning, which relies on formative assessment and regular feedback, used together to

help enhance a students learning by identifying specific strengths and needs (Guskey, 2010). As

determined throughout relevant research, STML positively affects the mathematical development

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 13

of students (Mevarech, 1985), making it an appealing choice to use in the mathematics

classroom. This versatile and easy to use approach to learning combines formative assessment

tasks with peer tutoring activities which can help solidify mathematical concepts and strategies

for students of all abilities, leading to an increase of confidence and efficacy beliefs towards

learning.

There are several other less formal methods that employ cooperative learning, which can

easily be implemented into a math class of any grade level. Naseem and Bano (2011) list and

describe several activities which can be easily adapted to help students learn a range of

mathematical concepts and procedures. These methods demonstrate how easy it can be to

incorporate interactive and social learning opportunities into lessons without a large amount of

preparation or materials. One such example, called jigsaw, requires students to first learn some

unique material which they then come back to teach to other group members. This would be a

great approach to use when students are required to learn various strategies or procedures around

a central topic, such as is the case with multiplication or division. Other examples include think-

pair-share tasks, which happens when students think about a question on their own at first, then

with a partner, and finally with other pairs or groups. A reverse method termed team-pair-solo

asks students to solve problems with a team at first, then with just a peer, and lastly on their own.

This method is used to build confidence and efficacy as students tackle more difficult material

with the help of other group members, helping them progress to a point where they can

understand difficult work on their own. Another simple approach which encourages

collaboration and cooperative group work is called numbered heads together. This strategy

involves groups of four students who are given the numbers one, two, three, or four. Questions

are given to the group as a whole, and students work together towards the correct answer. The

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 14

teacher then calls out a number, and all students given that number within the class have to share

their groups answer (Naseem & Bano, 2011). This strategy, like others, is effective in

developing a good understanding of mathematical concepts while promoting higher levels of

confidence as students work together towards the enhancement of their problem solving skills.

The Challenges of Cooperative Learning

Although the relevant research has indicated a multitude of advantages in various aspects

of the educational environment supporting cooperative learning, there are some drawbacks which

teachers should become aware of in order to realistically prepare for the incorporation of this

learning approach into the classroom. Knowing what problems may occur can help educators

take on a proactive approach which can help implement cooperative learning into the classroom

in a seamless manner. One such drawback, as indicated by Whicker, Nunnery and Bol (1997),

involves a level of passivity which can occur among lower-achieving students. Regardless of the

amount of cooperation and individual accountability encouraged by the teacher and other group

members, some students do not work well with other peers in a manner which encourages

effective leaning. These students prefer to take a passive role during academic tasks, which may

come from low self-efficacy beliefs due to past failures or from pressure from higher-ability

students to complete tasks quickly (Ross, 1995). These factors may lead students to question

their level of ability as they may feel they are being directly compared to their classmates when

they are required to work together for the successful completion of various tasks. This may

encourage some students to become reclusive rather than to take on a leadership role.

Another commonly known challenge of cooperative learning includes a students peer

orientation, which Hancock (2004) describes as the extent that a person prefers to work on

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 15

various tasks alone or with others. Sometimes students from any ability range prefer to complete

tasks or assigned work on their own rather than in a group. There are many people who have a

predisposition towards working independently rather than working with other learners. Since

students perform best when they are allowed to learn in their preferred manner (Hancock,

2004, p. 160), forcing these students to work with other peers towards common educational goals

would not be beneficial for anyone involved, as they may start to develop negative attitudes

towards learning and mathematics. These students need to be able to complete academic tasks in

their preferential manner; however teachers can start off small by slowly introducing them to the

benefits of cooperative learning which could then possibly open them up to the idea of social

interactions which encourage classroom learning. Pressuring a student to work in a group when

they clearly prefer to work alone can severely limit the amount of learning taking place, and can

instead create a hostile and unenjoyable classroom environment which depletes the purpose of

cooperative learning.

Another challenge which can occur during the implementation of cooperative learning

can result from a lack of feedback coming from educators. This type of instructional approach

does require the teacher to take a step back from having a leading role in the learning process,

however a severe lack of group intervention can lead to a limited amount of feedback-corrective

procedures, which may encourage students to learn incorrect material or develop misconceptions

towards the academic task (Mevarech, 1985). Cooperative learning groups are generally

heterogeneous in nature, however even high ability group members can become confused about a

new mathematical concept or strategy introduced in class. If this confusion is not corrected or if

inaccurate assumptions are not challenged, students can continue to engage in the learning

process developing incorrect knowledge. It is essential that teachers are proactive in finding a

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 16

balance between explicit teaching and passivity in the classroom, which can limit the need for

group remediation.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research paper was to explore cooperative learning in mathematics in

relation to the effect it can have on student achievement and motivation. By discussing problems

associated with traditional modes of teaching and current mathematical achievement trends, it is

clear that there is a present need for teachers to explore contemporary pedagogical approaches to

help increase mathematical proficiency among our students. Cooperative learning is an excellent

instructional method to use in all grade levels as it helps increase motivation and positive

mathematical attitudes, while concurrently promoting deeper levels of learning which can lead to

higher performance levels in math. As with any instructional approach, there are several

challenges associated with cooperative learning that teachers need to be familiar with in order to

adapt preventative measures which can help in the facilitation of a meaningful learning

environment where students are helping each other learn. Becoming proactive towards these

challenges and maintaining a positive attitude towards cooperative and collaborative learning

tasks can help our students gain a productive and valuable educational experience, which is a

goal many educators seek to attain on a daily basis.

Recommendations and Teacher Implications

Becoming knowledgeable about the positive aspects of cooperative learning, identifying

strategies that can help with the implementation of this interactive learning approach, and being

able to identify possible problematic areas in order to create a genuine and efficient learning

environment is a large task for educators to undertake. There are several recommendations

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 17

apparent within the relevant research on cooperative learning which can help ensure a more

smooth transition into a classroom which regularly uses social interactions to promote learning.

One such recommendation, as suggested by Nattiv (1994), would be to explicitly teach students

in cooperative learning groups how to help one another and how to ask for and receive help (p.

296). We sometimes take for granted the fact that many students have never been specifically

taught how to work in groups in a manner which helps promote deep understanding for all

involved learners. Teaching students various behaviours and strategies that they can use to assist

one another in the learning process can help them become more independent learners who shift

their dependency from the teacher to other group members. This would require a large amount of

start-up time as instructions, time to practice, and specific feedback would need to be given

before students would be expected to demonstrate a proficiency in the expectant behaviours

which help encourage learning. This will mean that teachers may need to exhibit patience in

order to observe the direct advantages of group learning (Whicker, Nunnery, & Bol, 1997;

Hsiung, 2012), however taking this time at the beginning of the year and revisiting these

strategies regularly can help facilitate efficient learning groups in an environment where all

students can achieve a level of success.

Creating a careful balance between taking on a passive teaching role and giving students

a large amount of regular feedback is another recommendation which can help ensure the

effectiveness of cooperative learning in mathematics. Students should be able to engage in a

deep level of learning with their peers in an effective manner after an initial start-up time,

however teachers need to be careful not to become passive observers of the learning taking place.

Students need to hear regular feedback concerning their performance as a group member. Ross

(1995) suggests that when students receive feedback on their performance during cooperative

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 18

learning activities, lower-ability students become more willing to seek out help, teacher

dependency requests decline, and students adapt their behaviour to become more specific to the

needs of the group. Without regular feedback, students may not be able to assess the

effectiveness of the learning taking place among group members. This can negatively affect the

learning occurring in cooperative groups, which can lead to misunderstandings and confusion

around mathematical concepts. Teachers need to make sure that they use careful and consistent

observations to help identify both the strengths and needs of the groupings in their classroom.

Using these observations to guide directive and explicit feedback which includes suggestions for

improvement and reminders of high expectations can help give students a clearer understanding

of what it means to be part of an effective cooperative environment (Ross, 1995).

Lastly, taking the time and dedication needed to promote a warm and welcoming

classroom atmosphere will be necessary for cooperative learning to work. Teachers need to make

sure they encourage a climate where students feel safe and supported in the learning process.

Students need to feel like they are able to take risks with their learning, where mistakes are met

with constructive feedback to grow and learn from instead of being a source of embarrassment

and ridicule. As suggested by Powell and Kalina (2009), learning occurs when students are

challenged and comfortable. In order to promote this type of environment teachers need to

develop a sense of trust and openness with students to encourage lesson engagement and

attentiveness. Consistently communicating, practising, and revisiting the notion that the

classroom is a safe place to experience unknown activities which promote learning will be

necessary in order for students to step out of their comfort zones to try new activities. We need to

challenge our students to expand what they know about themselves as learners in order to find

new and successful ways to promote deeper learning in mathematics. This will be a large step

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 19

towards the implementation of an instructional approach which focuses on student understanding

instead of rote procedures and memorization. In following this route we can help develop

confidence among our students which may help improve motivation and positive mathematical

attitudes, while concurrently promoting life-long learners.

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 20

References

Brochu, P., Deussing, M.A., Houme, K, & Chuy, M. (2013). Measuring up: Canadian results of

the OECD PISA study. Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. Retrieved from

http://cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/318/PISA2012_CanadianRep

ort_EN_Web.pdf

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Education (2012). CRT results 4

year trend. K-12 School Profile System. Retrieved from http://www.education.gov.nl.ca/

Guskey, T. R. (2010). Lessons of mastery learning. Educational Leadership, 68(2), 52-57.

Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com

Hancock, D. (2004). Cooperative learning and peer orientation effects on motivation and

achievement. Journal of Educational Research, 97(3), 159-166.

doi:10.3200/JOER.97.3.159-168

Hsiung, C.M. (2012). The effectiveness of cooperative learning. Journal of Engineering

Education, 101(1), 119-137. Retrieved from http://www.jee.org

Ifamuyiwa, S. A., & Akinsola, M. K. (2008). Improving senior secondary school students'

attitude towards mathematics through self and cooperative-instructional

strategies. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science &

Technology, 39(5), 569-585. doi:10.1080/00207390801986874

Majoka, M., Dad, M., & Mahmood, T. (2010). Student team achievement division (STAD) as an

active learning strategy: Empirical evidence from mathematics classroom. Journal of

Education & Sociology, (4), 16-20. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com

Mevarech, Z. R. (1985). The effects of cooperative mastery learning strategies on mathematics

achievement. Journal of Educational Research, 78(3), 72-377. Retrieved from

http://web.ebscohost.com

Naseem, S., & Bano, R. (2011). Cooperative learning: An instructional strategy. Technolearn:

An International Journal of Educational Technology, 1(1), 79-85. Retrieved from

http://web.ebscohost.com

COOPERATIVE LEARNING IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION 21

Nattiv, A. (1994). Helping behaviors and math achievement gain of students using cooperative

learning. Elementary School Journal, 94(3), 285. Retrieved from

http://web.ebscohost.com

Powell, K. C., & Kalina, C. J. (2009). Cognitive and social constructivism: Developing tools for

an effective classroom. Education,130(2), 241-250. Retrieved from

http://web.ebscohost.com

Ross, J. A. (1995). Effects of feedback on student behavior in cooperative learning groups in a

grade 7 math class. Elementary School Journal, 96(2), 125. Retrieved from

http://web.a.ebscohost.com.

apkova, A. (2014). The relationships between the traditional beliefs and practice of

mathematics teachers and their students achievements in doing mathematics tasks.

Problems Of Education In The 21St Century, 58, 127-143. Retrieved from

http://web.a.ebscohost.com.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1988). When good teaching leads to bad results: the disasters of well-taught

mathematics courses.Educational Psychologist, 23145-166.

doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2302_5

Tarim, K., & Akdeniz, F. (2008). The effects of cooperative learning on Turkish elementary

students' mathematics achievement and attitude towards mathematics using TAI and

STAD methods. Educational Studies In Mathematics, 67(1), 77-91. doi:10.1007/s10649-

007-9088-y

Tarim, K. (2009). The effects of cooperative learning on preschoolers mathematics problem-

solving ability. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 72(3), 325-340.

doi:10.1007/s10649-009-9197-x

Webb, N., Franke, M., De, T., Chan, A., Freund, D., Shein, P., & Melkonian, D. (2009). 'Explain

to your partner': teachers' instructional practices and students' dialogue in small groups.

Cambridge Journal Of Education, 39(1), 49-70. doi:10.1080/03057640802701986

Whicker, K. M., Bol, L., & Nunnery, J. A. (1997). Cooperative learning in the secondary

mathematics classroom. Journal Of Educational Research, 91, 42-48.

doi:10.1080/00220679709597519

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Speech and Language Stimulation Techniques For ChildrenDocumento18 pagineSpeech and Language Stimulation Techniques For ChildrenKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN91% (22)

- AI ApplicationsDocumento13 pagineAI Applicationss10_sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsDa EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsNessuna valutazione finora

- Argumentative Writing Lesson PlanDocumento9 pagineArgumentative Writing Lesson Planapi-515368118Nessuna valutazione finora

- Psychological Perspective of The SelfDocumento17 paginePsychological Perspective of The Selfkimmy x100% (3)

- Sample Thesis2Documento25 pagineSample Thesis2Lemuel KimNessuna valutazione finora

- Successfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms: Research in K-12 and Teacher EducationDa EverandSuccessfully Implementing Problem-Based Learning in Classrooms: Research in K-12 and Teacher EducationThomas BrushNessuna valutazione finora

- Action Research DSMDocumento26 pagineAction Research DSMshahidshaikh76433% (3)

- Increasing Student Learning in Mathemtics Through Collaborative Teaching StrategiesDocumento24 pagineIncreasing Student Learning in Mathemtics Through Collaborative Teaching StrategiesRecilda Baquero100% (3)

- Teaching Mathematics in the Middle School Classroom: Strategies That WorkDa EverandTeaching Mathematics in the Middle School Classroom: Strategies That WorkNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Learning PhilosophyDocumento9 pagineTeaching Learning PhilosophyEron Roi Centina-gacutanNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Methaphor Theory-Journal of Cognitive Semiotics PDFDocumento413 pagineConceptual Methaphor Theory-Journal of Cognitive Semiotics PDFSofianti100% (1)

- Output For Program EvaluationDocumento31 pagineOutput For Program EvaluationLordino AntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- Outstanding Practices of Mathematics Teachers Using Primals in Grade 7Documento68 pagineOutstanding Practices of Mathematics Teachers Using Primals in Grade 7marygrace cagungunNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan (Cone of Experience)Documento5 pagineLesson Plan (Cone of Experience)Katrina Rempillo69% (13)

- Cognitive TheoryDocumento62 pagineCognitive TheoryAyie Juliati Jamil100% (1)

- Content Language Integrated Learning Teacher Professional TrainingDocumento60 pagineContent Language Integrated Learning Teacher Professional TrainingMaria pex100% (1)

- GROUP 6 HUMSS A DISIPLINA Research PaperDocumento20 pagineGROUP 6 HUMSS A DISIPLINA Research PaperNathalie Uba100% (1)

- Lessons in Grade 10 Mathematics For Use in A Flipped ClassroomDocumento12 pagineLessons in Grade 10 Mathematics For Use in A Flipped ClassroomGlobal Research and Development ServicesNessuna valutazione finora

- Intervention Program in Enhancing Mathematics Program of Grade 10 Students at Navera Memorial National High SchoolDocumento7 pagineIntervention Program in Enhancing Mathematics Program of Grade 10 Students at Navera Memorial National High Schoolandrea marananNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Peer Tutoring Teaching StrategDocumento46 pagineEffect of Peer Tutoring Teaching StrategNelly Jane FainaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematics Remediation For Grade-Seven Pupils of Mindanao State University-Maigo School of Arts and TradesDocumento18 pagineMathematics Remediation For Grade-Seven Pupils of Mindanao State University-Maigo School of Arts and TradesRobie Elliz Tizon100% (1)

- The 5 EsDocumento24 pagineThe 5 EsNimmi MendisNessuna valutazione finora

- Cherry - Chapter IDocumento77 pagineCherry - Chapter Itoti MalleNessuna valutazione finora

- B2 2020AResearch Yongco SDODocumento10 pagineB2 2020AResearch Yongco SDOAbril Biente SincoNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Collaborative Learning in Enhancing The Grades in Mathematics of Grade 11 Stem StudentsDocumento35 pagineEffects of Collaborative Learning in Enhancing The Grades in Mathematics of Grade 11 Stem StudentskiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Paper - Tiffany NGDocumento52 pagineFinal Paper - Tiffany NGjhe maligayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Elementary Grade Learners Learning Difficulties Chapter 1 3 Edited 7-16-2022Documento30 pagineElementary Grade Learners Learning Difficulties Chapter 1 3 Edited 7-16-2022Raima CABARONessuna valutazione finora

- Shelby Rose Te808 f18Documento24 pagineShelby Rose Te808 f18api-471972822Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter I FinalDocumento47 pagineChapter I FinalGerland Gregorio EsmedinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Yasay Jerbee Maed Math Final Manuscript Final 1Documento104 pagineYasay Jerbee Maed Math Final Manuscript Final 1tumamporowena7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Action ResearchDocumento40 pagineAction ResearchCleofe SobiacoNessuna valutazione finora

- Differentiated InstructionDocumento23 pagineDifferentiated InstructionarcanmacNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematics Teaching in Primary and Secondary Schools: Universiti Teknologi MalaysiaDocumento16 pagineMathematics Teaching in Primary and Secondary Schools: Universiti Teknologi MalaysiaushaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abuda Et Al. SIMs Effect On The Mathematics Achievement of SARDOSDocumento11 pagineAbuda Et Al. SIMs Effect On The Mathematics Achievement of SARDOSBenAbudaNessuna valutazione finora

- VND - Openxmlformats Officedocument - Wordprocessingml.document&rendition 1Documento32 pagineVND - Openxmlformats Officedocument - Wordprocessingml.document&rendition 1Raima CABARONessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 1 1 - Acabal Dequina Espasyos Quibot VillafuerteDocumento20 pagineCHAPTER 1 1 - Acabal Dequina Espasyos Quibot VillafuerteQuibot JayaNessuna valutazione finora

- 192088-Article Text-490064-1-10-20200217Documento15 pagine192088-Article Text-490064-1-10-20200217audeza maurineNessuna valutazione finora

- 9.chapter IiDocumento9 pagine9.chapter IiLee GorgonioNessuna valutazione finora

- English FormDocumento9 pagineEnglish FormSurya PutraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1Documento23 pagineChapter 1Buena flor AñabiezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematics Education 1 Running Head: Mathematics EducationDocumento14 pagineMathematics Education 1 Running Head: Mathematics Educationapi-348970908Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dawis Es Action R Jayann Roldan g2Documento4 pagineDawis Es Action R Jayann Roldan g2JAY ANN ROLDANNessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry-Based Approach As Learning Enhancement of Grade 9 Students in Quadratic Equation: A Lesson StudyDocumento7 pagineInquiry-Based Approach As Learning Enhancement of Grade 9 Students in Quadratic Equation: A Lesson StudyPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Education, The Immediate Need For Teachers To Acquire The Needed Teaching SkillsDocumento7 paginePhilippine Education, The Immediate Need For Teachers To Acquire The Needed Teaching SkillsRoderick Lee TipoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting in Blended Learning On The Academic Performance of Grade34 1Documento28 pagineFactors Affecting in Blended Learning On The Academic Performance of Grade34 1Marchee AlolodNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring Teachers' Practices in Teaching Mathematics and Statistics in Kwazulu-Natal SchoolsDocumento13 pagineExploring Teachers' Practices in Teaching Mathematics and Statistics in Kwazulu-Natal SchoolsReynante GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Untitled DocumentDocumento9 pagineUntitled DocumentIsidora TamayoNessuna valutazione finora

- Enriching The Teaching of Pie Chart Using Cooperative Learning As A Strategy: A Quasi - Experimental ResearchDocumento9 pagineEnriching The Teaching of Pie Chart Using Cooperative Learning As A Strategy: A Quasi - Experimental ResearchPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 183899Documento16 paginePaper 183899John Lester LabiñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cherry ThesisDocumento83 pagineCherry Thesistoti MalleNessuna valutazione finora

- Teachers As Curriculum Leaders: A. PedagogyDocumento14 pagineTeachers As Curriculum Leaders: A. PedagogySmp ParadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Parents Participation Towards The Modular Learning To Grade 11 Students of IACCESS S.Y. 2020-2021Documento13 pagineParents Participation Towards The Modular Learning To Grade 11 Students of IACCESS S.Y. 2020-2021Nova Perez CorderoNessuna valutazione finora

- Co Operative Learning in The Teaching of Mathematics in Secondary EducationDocumento29 pagineCo Operative Learning in The Teaching of Mathematics in Secondary EducationArceo AbiGailNessuna valutazione finora

- PR2 GROUP 3 ManuscriptDocumento29 paginePR2 GROUP 3 ManuscriptdrixkunnNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Odoy 1Documento33 pagineResearch Paper Odoy 1Via Krysna CarriedoNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects and Challenges To Implement Differentiated Mathematics Teaching Among Fourth 2100-13204-1-PBDocumento11 pagineEffects and Challenges To Implement Differentiated Mathematics Teaching Among Fourth 2100-13204-1-PBDijana VučkovićNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Together (Repaired)Documento11 pagineLearning Together (Repaired)Cherry mae Delos santosNessuna valutazione finora

- ManuscriptDocumento34 pagineManuscriptdrixkunnNessuna valutazione finora

- ACTION ROSAL - Docx BRIGOLIDocumento14 pagineACTION ROSAL - Docx BRIGOLIAllen EnanoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 1 Research PaperDocumento11 pagineCHAPTER 1 Research Paperjohn kingNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Report - FinalDocumento22 pagineWritten Report - Finalapi-471893759Nessuna valutazione finora

- Article Review Sgdc5034-RosmainiDocumento7 pagineArticle Review Sgdc5034-RosmainiVanessa SchultzNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Attendance: How To Get Kids To Come To School 1Documento25 pagineRunning Head: Attendance: How To Get Kids To Come To School 1Willie HarringtonNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis After DefenseDocumento43 pagineThesis After DefenseLiezel GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Unit Plan With Eticpc AppendixDocumento27 pagineSample Unit Plan With Eticpc Appendixapi-282262206Nessuna valutazione finora

- Action Research - Geometry Content Knowledge DSMDocumento26 pagineAction Research - Geometry Content Knowledge DSMshahidshaikh764Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study 2Documento3 pagineCase Study 2Princes Joy Garsuta ArambalaNessuna valutazione finora

- It Is Not Just The Solution Anymore: Carol Brown Alliance, NebraskaDocumento54 pagineIt Is Not Just The Solution Anymore: Carol Brown Alliance, NebraskaHenry LanguisanNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Application Activities in MathematicsDocumento46 paginePractical Application Activities in Mathematicsjbottia1100% (1)

- Cidam Example PerdevDocumento6 pagineCidam Example PerdevJoyce Lee De Guzman100% (3)

- Introduction To General PsychologyDocumento33 pagineIntroduction To General PsychologyMarven CA, MENessuna valutazione finora

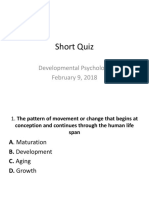

- Short QuizDocumento16 pagineShort QuizMarry Jane Rivera Sioson0% (1)

- Anders On The Pseudo Concreteness of Heidegger39s PhilosophyDocumento36 pagineAnders On The Pseudo Concreteness of Heidegger39s Philosophymmehmet123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Questions Chapter 4 and 5 With AnswersDocumento2 pagineSample Questions Chapter 4 and 5 With Answers张雨婷Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gestalt Theory - Visual and Sonic GestaltDocumento6 pagineGestalt Theory - Visual and Sonic GestaltJaime RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Zakaria Cheglal Social CognitionDocumento12 pagineZakaria Cheglal Social Cognitionعبد الرحيم فاطميNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning The Study of Phonetics and Phonology: Rizal Technological University Pasig Campus College of EducationDocumento5 pagineLearning The Study of Phonetics and Phonology: Rizal Technological University Pasig Campus College of EducationManilyn PericoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Psychomotor or Kinesthetic DomainDocumento2 pagineThe Psychomotor or Kinesthetic DomainWiljohn de la Cruz0% (1)

- The Effects of Color To Short Term Memory in Physical Science ContextDocumento7 pagineThe Effects of Color To Short Term Memory in Physical Science ContextHannabee_14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Native English Students Learning in English:: Reviewing and Re Ecting On The ResearchDocumento9 pagineNon-Native English Students Learning in English:: Reviewing and Re Ecting On The ResearchMatt ChenNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of An Effective Teacher: Prepared By: Lomboy, Jessica S. Beed-IiDocumento19 pagineCharacteristics of An Effective Teacher: Prepared By: Lomboy, Jessica S. Beed-Iijeny roseNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive Communicative and Alternative Treatment ApproachesDocumento51 pagineCognitive Communicative and Alternative Treatment ApproachesKrithikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Before The Lesson Lesson Proper After The Lesson: List of Learning TasksDocumento2 pagineBefore The Lesson Lesson Proper After The Lesson: List of Learning TasksJholeen OrdoñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 1 TesolDocumento5 pagineAssignment 1 TesolJimmi KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineMotivation Lesson Planapi-459599397Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1 The Teacher: Components of Effective TeachingDocumento23 pagine1 The Teacher: Components of Effective TeachingJayCesarNessuna valutazione finora

- Let Reviewer ChecheDocumento71 pagineLet Reviewer ChecheCarmel Atuy CabalesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Psychology of ThinkingDocumento9 pagineThe Psychology of Thinkingahassana4064Nessuna valutazione finora

- Development of Pivot 4A Learner'S Material: What I Need To Know?Documento1 paginaDevelopment of Pivot 4A Learner'S Material: What I Need To Know?Charmaine Hugo100% (1)