Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Working Theory of Practice Upload

Caricato da

api-245380928Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Working Theory of Practice Upload

Caricato da

api-245380928Copyright:

Formati disponibili

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-.

/%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% '%

Working Theory of Practice Claire Wang University of Pennsylvania

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% 9%

My student teaching experience at Northeast High School has made me intrigued by the perceptiveness of adolescent students in addition to the diversity of students in a single class. Many of my students are not afraid to voice their opinions in class, and their voices are informative for me to gauge student understanding, frustrations, misconceptions, engagement, strengths, and weaknesses. Right when I think my students are not paying attention, they surprise me with a quick comment or inquisitive question. Something that has perplexed me over the past few months is the seeming disconnect between what students say they want and their follow-up actions. On the first day of class, my students were asked to fill out an information sheet for attendance records. At the bottom of the sheet, my classroom mentor asked the students to write down their plans for after high school. My mentor made it clear that it was acceptable to not have a plan yet. As I flipped through the sheets for my class I read that many of my students want to attend college in order to pursue careers in medicine, nursing, law, culinary arts, athletics, and business. Although many of my students expect to graduate from high school and attend college, their classwork do not reflect their great ambitions. When I entered my field placement I expected students to be able to recognize that their grades are directly influenced by the completion of their assignments both within and outside of class, yet my students are still surprised when they receive no credit on assignments they never turned in. Homework is an area where I see discrepancies between student desires and student actions. I have noticed that many students lose, forget, do not do, or copy homework. It is rare that more than half of my class will turn in homework, and only a few of the remaining students will turn in late work for partial credit. The impression I got was that the majority of my students did not really care about their grades. My classroom mentor and I even dedicated an entire class period to insure that all students could access their grades and the class website. Even with reminders, few students checked their grades and thus many students were shocked to find out that they were on the border to fail the class. Consequently, I was surprised when interim reports were distributed because I saw a completely different side of my students. My students were flocking to me with questions about their grades and make-up work. At interim, 18 of my 33 students were at risk of failing the first marking period. A closer examination of individual students grades indicated that the low grades were due to students not turning in or making up missed work and not because of a lack of intellectual or ability level. It disheartens me when I see bright students in danger of failing because they do not turn in assignments.

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% :%

Throughout the past three months of student teaching I have been brainstorming ways to encourage students to do their class assignments and homework. Rewards, such as extra credit, candy, and even stamps, seem to bring about the highest turnout in completed assignments. At the beginning of December I decided to make a packet, which would be used for one full week. The packet consisted of worksheets that I would use as guided notes, classwork, homework assignments, or references. Before I passed out the packets I made it clear to the students that I was giving them this packet for the week, and it is their responsibility to keep track of their packet. As a reward for having the packet at the end of the week, students received 8 points regardless of effort put into the completion of the packet. There were two reasons I chose to create this packet (see Appendix A for packet). The first reason was my attempt to help students stay organized, which in this scenario meant holding onto their packet for the entire week. By providing students with the materials for the week, they already have everything that I could assign in one place. The second reason for creating this packet was to allow students to be able to know and see what they would be doing and learning in class for the rest of the week. There was initial panic amongst the students, I found that after my first homework check students were eager to show me that they had their packet. Students also appeared more prepared because they would have their packets out and ready before I even asked for them to take it out. Furthermore, the use of a weekly packet allowed me to reach one of my students, Megan, who I have been having trouble engaging in class (see Appendix B). I was more proactive with Megan than the rest of the students. I checked in with her every day, something we had agreed upon at the beginning of the marking period, about how she was feeling that day and whether she got the homework assignment or had a completed assignment to show me. My check-ins with the packet seemed to motivate Megan more than anything else I have tried this school year, but the use of a weekly packet did not provide me with information on the value of homework in the classroom. The packet was useful for me to assess what I needed to review with my students (see Appendix C). As an extension to my informal teacher inquiry, I would like to explore strategies that I can implement in the classroom that would utilize homework as a formative assessment to make students more accountable for their own learning. More specifically, I would like to address the question, What happens to students learning when a teacher uses homework to facilitate peer and self assessment?

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% ;%

So far I have been following my classroom mentors late work policy, and I plan to continue implementing her policies in my classroom for the remainder of the year. The penalty for the first marking period was lenient with a deduction of 5 points each day an assignment was late, however, for the second marking period, late work automatically gets half credit. I have noticed that students are very aware of if and when they turn in their work after receiving their first marking period grades. My classroom mentor also grades assignments for accuracy, including homework, which I have adopted. A homework grade based on accuracy of answers increases the stakes for students, which in turn may be a factor for the prevalent copying seen on assignments. I am curious about different practices for assigning homework that aim towards student learning more than student grades. In Cathy Vatterotts (2011) article, Making Homework Central to Learning, she claims two flaws in the typical practice of grading homework in the United States. The first flaw is that both students and teachers tend to view homework grades as rewards for working rather than as feedback about learning (p. 60). I think it would be fair to say that this is similar to how homework is portrayed in my classroom. Homework is always turned in at the beginning of class without any time for questions or discussion. The only review that occurs is when it is evident that the majority of students are not grasping a concept, and this review takes place after homework has already been graded. I do try to write constructive feedback for students on homework, but it is difficult to determine whether students even look at my comments. The second flaw that Vatterott (2011) claims is that students fail to connect homework to assessment (60). As I mentioned earlier, I choose the type of homework that students have based on my learning objectives. The assessments that I give my students are also based on these learning objectives; therefore, the homework I choose has a definitive connection with what I hope students will learn in class. As of now, the students are not explicitly given the learning objectives although they are listed on a large portable whiteboard at the front of the room. One strategy I could implement to make homework more meaningful to students is to familiarize students with the learning objectives and explicitly tie in the objectives to each homework assignment. In order to get to the core of student learning, I will need to know how students understand their own learning. Do their views align more with a fixed mindset or growth mindset (Dweck, 2010, p. 26)? I know that many of my colleagues at other schools have spent time in

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% &%

class discussing the idea of fixed and growth mindsets, and I think a lesson on growth mindsets could be valuable for students because their perceptions of their own intelligence affect their learning. Knowledge of student perceptions could also help guide my approach to implementing homework in the classroom. In my classroom, I would like to introduce the idea of the development of intelligence to my students to reinforce the focus on effort and to motivate students to overcome challenging work (Dweck, 2010, p. 27). After assessing student beliefs about their intelligence, it is imperative for me to follow-up by assessing my students thoughts and feelings on homework. I think providing students with a survey on their perception of homework allow all students the opportunity to voice their opinion. The surveys will provide me with insight into how students view the purpose of homework and possibly how their previous teachers have utilized homework in their classes. My student teaching experience has exposed me to many different views on homework ranging from the belief that homework is a waste of time to the belief that homework should be assigned daily. According to Harris Cooper et al. (2006), homework has a positive influence on achievement, and there are stronger correlations for grades 7-12 than for K-6 (p. 3). There are multiple variations of homework incorporating factors such as amount, purpose, frequency, degree of choice, degree of individualization, and social context. The purpose of homework in my classroom is to review class material and to provide students with the chance to practice applying the new material. Homework is never intended to be busy work or punishment, and students usually have homework two to three nights a week. If I do not cover enough material in class for students to be able to independently complete the intended homework then I save it for when the homework would serve as a review of content rather than a preview of content. In some cases I may ask students to do a section of original homework assignment so they can review the material that was covered. In Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment, Black & Wiliam (1998) claim, the main problem is that pupils can assess themselves only when they have a sufficiently clear picture of the targets that their learning is meant to attain (p. 7). This ties back into the explicit use of learning objectives to inform students of my expectations. The authors also state that self-assessment is an essential component of formative assessment, or homework in this case, in order for students to understand the main purposes of their learning and thereby grasp what they need to do to achieve (Black & Wiliam, 2003, p. 8). The simplest

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% <%

way I can have students self-assess their understanding of content material is to survey both students confidence level while completing homework and students confidence on the accuracy of their answers. A way to check for misperceptions of student understanding is to compare students self-reported confidence with the actual number of correct answers. Another way to tie homework in with assessments would be to correlate amount of homework completed with assessment scores (see Appendix D). I think that the designation of a homework partner could be the first step towards familiarizing students with the idea of peer assessments. The type of homework partner that I have in mind is not someone who I would work with to complete homework. Instead, a homework partner would be someone who I could collaborate with after completing homework, and, if necessary, I could also discuss homework questions with my partner if we disagree. A feedback strategy that could be use for peer assessment is implementing peer review of homework where students will make comments on each others assignments as opposed to teacher graded homework. Then, I can choose to collect student homework to assess peer assessment, which will provide me with data on the effectiveness of the feedback for student learning. I am interested in using this strategy because a study done by Ruth Butler in 1988 showed the use of only comments led to the greatest learning in comparison to using marks or a combination of comments and marks (Black et. Al, 2003, p. 43). Implementation of homework as an opportunity for peer and self-assessment will require proper scaffolding on my part, and I believe that self-assessment would be easier to enact initially than peer-assessment. Black et al. (2003) argue that feedback is not useful if it does not indicate what had been achieved nor what steps to take next (p. 44). Comments such as well done, please elaborate, and why? will most likely mean nothing to students without specific feedback about how students can improve their work. Consequently, the implementation of effective peer assessments will take time to scaffold for students who are not used to reviewing each others work. I hope that the time spent to scaffold peer and self-assessments will facilitate student understanding and learning in the classroom. In my current student teaching practice I do not believe that homework is valuable to the majority of my students, but I believe homework has a place in a classroom and it can have a positive effect on student learning when used correctly. I have now been in Penns Teacher Education Program for five months, and a large frame of focus across the program has been on

!"#$%&'&(%)*+,-./%012*+3%*4%5+678-72% %

% =%

the use of differentiation in the classroom. I believe that homework is another means to differentiate class content for students who may need extra practice or exposure to class content outside of the classroom. The use of homework as a formative assessment in the classroom will emphasize the qualitative feedback for both students and teachers rather than on the assigned grade. For the remainder of my time at Northeast High School I hope to examine whether student learning is affected when homework is used for peer or self-assessments. As Vatterott (2011) stated, Its not about homeworks value for the grade, but homeworks value for learning (p. 62).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Cambridge International AS and A Level English Language: Paper 4Documento46 pagineCambridge International AS and A Level English Language: Paper 4Musss100% (1)

- Mixed Tenses ExercisesDocumento5 pagineMixed Tenses ExercisesmariamcarullaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fall Video AnalysisDocumento3 pagineFall Video Analysisapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- HW Implementations Follow-Up Survey 2ndDocumento2 pagineHW Implementations Follow-Up Survey 2ndapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz 7aDocumento2 pagineQuiz 7aapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Extra Electron Configuration PracticeDocumento1 paginaExtra Electron Configuration Practiceapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Obs Apr 1 Math PD 4 CompleteDocumento5 pagineWang Obs Apr 1 Math PD 4 Completeapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Lps Feb 27 2014Documento3 pagineWang Lps Feb 27 2014api-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Lps Apr 1 2014Documento2 pagineWang Lps Apr 1 2014api-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Artifact 7Documento6 pagineArtifact 7api-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Obs Feb 27 PD 7 Claires Pams Feedback CompleteDocumento4 pagineWang Obs Feb 27 PD 7 Claires Pams Feedback Completeapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wang Spring Journal 10-Video Analysis Assignment ReflectionDocumento3 pagineWang Spring Journal 10-Video Analysis Assignment Reflectionapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Homework SurveyDocumento2 pagineFinal Homework Surveyapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Homework SurveyDocumento2 pagineChemistry Homework Surveyapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz 10 Global ADocumento2 pagineQuiz 10 Global Aapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Educ 627 B Cullen C Wang Unit Plan 2-2Documento58 pagineEduc 627 B Cullen C Wang Unit Plan 2-2api-252942769Nessuna valutazione finora

- Weebly Wang Spring Journal 2 Cross Visit ReflectionDocumento4 pagineWeebly Wang Spring Journal 2 Cross Visit Reflectionapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 2ndDocumento1 paginaChemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 2ndapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 7thDocumento1 paginaChemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 7thapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 2ndDocumento1 paginaChemistry Homework Survey Artifact Analysis 2ndapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wtop Annotated BibliographyDocumento4 pagineWtop Annotated Bibliographyapi-245380928Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pak Studies Environment of Pakistan 2059 2 WorkshopDocumento22 paginePak Studies Environment of Pakistan 2059 2 WorkshopTaha Yousaf100% (1)

- Trainer Competency ModelDocumento4 pagineTrainer Competency ModelpattapuNessuna valutazione finora

- Level 3 BTEC Course in Applied Science PDFDocumento3 pagineLevel 3 BTEC Course in Applied Science PDFNeen NaazNessuna valutazione finora

- Maths p12 PDFDocumento20 pagineMaths p12 PDFNatsu DragneelNessuna valutazione finora

- GetPractHallTicketttt DoDocumento1 paginaGetPractHallTicketttt DoS KkNessuna valutazione finora

- English 10 3rd and 4thDocumento7 pagineEnglish 10 3rd and 4thVince Rayos Cailing0% (1)

- Muet Jadual PDFDocumento1 paginaMuet Jadual PDFExplode ArenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Aro Guntur (Army Recruitment Rally at Police Parad Ground, Ongole From 03JUL 2019 TO - 15 JUL 2019)Documento5 pagineAro Guntur (Army Recruitment Rally at Police Parad Ground, Ongole From 03JUL 2019 TO - 15 JUL 2019)Anilkumar KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Eye Accessing Cues: Take A Moment To Consider The Following QuestionsDocumento6 pagineEye Accessing Cues: Take A Moment To Consider The Following Questionsecartetescuisses100% (1)

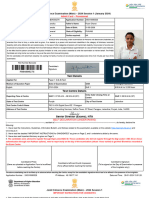

- Admit CardDocumento4 pagineAdmit CardprinceNessuna valutazione finora

- CPE Student's.handbook 2013Documento36 pagineCPE Student's.handbook 2013David Hayes100% (1)

- Wisdom Institute Brochure 2022Documento5 pagineWisdom Institute Brochure 2022Chinmay MarkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Api 510Documento27 pagineApi 510Alby DiantonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of The Bangor Dyslexia Test (BDT) For Use With AdultsDocumento38 pagineEvaluation of The Bangor Dyslexia Test (BDT) For Use With AdultsFiza JahanzebNessuna valutazione finora

- BiophysicsDocumento16 pagineBiophysicsNurarief AffendyNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Reporting and Analysis by CA K K Ramesh (FRA)Documento4 pagineFinancial Reporting and Analysis by CA K K Ramesh (FRA)Nilesh kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring English Language AnxietyDocumento19 pagineExploring English Language AnxietyPrimo AngeloNessuna valutazione finora

- 0625 s11 Ms 62 PDFDocumento3 pagine0625 s11 Ms 62 PDFArhaan SawhneyNessuna valutazione finora

- CIVE 423 Syllabus 2017Documento4 pagineCIVE 423 Syllabus 2017HazemNessuna valutazione finora

- LLB DissertationDocumento3 pagineLLB Dissertationshamailar7595Nessuna valutazione finora

- Retail ManagementDocumento7 pagineRetail ManagementLeiNessuna valutazione finora

- Study in GermanyDocumento20 pagineStudy in GermanyCaujman CVNessuna valutazione finora

- ToR For Geotechnical EngineerDocumento2 pagineToR For Geotechnical EngineerMEWNessuna valutazione finora

- Brittany Flavel - ResumeDocumento1 paginaBrittany Flavel - Resumeapi-302415360Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Use of Caution: Accuracy in Writing (2) CautionDocumento3 pagineThe Use of Caution: Accuracy in Writing (2) CautionAndiko Putro SuryotomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rdb-Elseif Company LTD.: Job DescriptionDocumento1 paginaRdb-Elseif Company LTD.: Job DescriptionAsif ChahudaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Business Administration FIN 414 - Course SyllabusDocumento9 pagineDepartment of Business Administration FIN 414 - Course SyllabusJessa EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF)Documento31 paginePhilippine Qualifications Framework (PQF)james lumakangNessuna valutazione finora