Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Court of Appeal 14 Nov 2007

Caricato da

api-53711077Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Court of Appeal 14 Nov 2007

Caricato da

api-53711077Copyright:

Formati disponibili

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF NEW ZEALAND CA83/06 [2007] NZCA 499

BETWEEN

TELECOM NEW ZEALAND LIMITED Appellant SINTEL-COM LIMITED Respondent

AND

Hearing: Court: Counsel:

26 June 2007 Glazebrook, Hammond and Wilson JJ J S Kos QC and J K Goodall for Appellant J R Billington QC and C J R Baird for Respondent 14 November 2007 at 4 pm JUDGMENT OF THE COURT

Judgment:

A B

The appeal is dismissed. The respondent will have costs of $6,000 and usual disbursements.

REASONS OF THE COURT (Given by Hammond J) Table of Contents Introduction Background The basis of the strike out application in the High Court The terms of the debenture Was there an assignment of the choses in action? The effect of the assignment A limited exception? Discussion Conclusion Para No [1] [4] [15] [18] [19] [21] [29] [44] [50]

TELECOM NZ LTD V SINTEL-COM LTD CA CA83/06 [14 November 2007]

Introduction

[1]

This is an appeal from a judgment of Rodney Hansen J reported at (2006) 9

NZCLC 264,040, in a commercial cause in which Sintel seeks damages of $61 million against Telecom. [2] Telecom sought to strike out certain causes of action in Sintels claim. The

High Court Judge declined to do so. Telecom now appeals to this Court. [3] There are two issues before us. First, can a person who has assigned assets

(in this instance, causes of action) to a debenture holder by way of security, deal with those assets by suing on them without redeeming the debenture, or obtaining the consent of the debenture holder? Secondly, if the suit can be brought, can Sintel do so in the particular circumstances of this case? Background

[4]

Sintel was in the business of providing audiotext telecommunications

services, primarily of adult entertainment services accessed by telephone, and aimed at persons in Korea. [5] Telecom contracted to provide Sintel with telecommunications services under

a Switched Transit Agreement dated 2 October 1997. [6] The ANZ Banking Group (New Zealand) Limited (ANZ) entered into a

US$3.5 million facility agreement with Sintel on 3 October 1997. On that same date Sintel and ANZ entered into a debenture, on usual terms, which assigned absolutely, by way of mortgage, all Sintels present and future choses in action to ANZ (the ANZ debenture). [7] Sintel gave notice of the assignment to ANZ of the rights under the Telecom

contracts to Telecom on 3 October 1997.

[8]

Telecom agreed to deposit money due to Sintel (which it would receive from

Korea Telecom) into a specific bank account at ANZ. Telecom allegedly failed to make the deposits required. This resulted in a claim by ANZ against Telecom. [9] On the application of a third party, on 26 August 1999 Sintel was placed in

liquidation. ANZ thereupon appointed receivers, as it was entitled to do under the ANZ debenture. At this time, Sintels debt to ANZ was approximately $2.5 million. [10] Differences then arose between Telecom and Sintel as to the amounts payable

to Sintel under the Telecom contract, and between Telecom and ANZ as to Telecoms liability for its failure to make payments direct to ANZ. [11] These disputes between the parties were all supposedly resolved by a

settlement agreement dated 15 June 2000. The agreement provided for the full and final settlement of all disputes between the parties, for Telecom to pay ANZ $2.225 million, and for ANZ to execute a deed of assignment of the facility agreement and its debenture to Telecom. This assignment was subject to the

assignment back to ANZ of a 28 percent share of the interests arising under the instrument. This proportion reflected the unsatisfied portion of Sintels debt to ANZ which, by the time the settlement was entered into, had risen to $2.955 million. All of these things were duly attended to. The receivers retired in April 2001. [12] On 2 April 2004 Sintel commenced proceedings in the High Court against

Telecom. The essential claim is that Telecom failed to properly account to Sintel for payments received from Korea Telecom. Sintel alleges that Telecom is indebted to it in a sum of $NZ61 million. [13] Seven causes of action were pleaded, alleging various breaches of contract,

misrepresentation, breaches of fiduciary duty, and deceit. [14] Telecom accepts that the seventh cause of action which seeks to have the

15 June settlement agreement set aside on the footing that Sintels liquidators and receivers were induced to enter into the settlement agreement by Telecom misrepresenting the amount of its indebtedness to Sintel cannot properly be struck

out.

So the fate of the strike out application will not be determinative of this

litigation. The basis of the strike out application in the High Court

[15]

Telecoms application was that the first six causes of action should all be

struck out for want of a reasonable cause of action, and abuse of process, because: (a) Sintel has assigned those rights under the ANZ debenture. therefore has no causes of action on which to proceed. (b) Sintel is acting in breach of contract by bringing its actions. The ANZ debenture expressly prohibits unauthorised dealings with secured property. (c) Sintel requires the consent of the debenture holder to bring the proceeding. Such consent has not been obtained. [16] Rodney Hansen J rejected those arguments. It is convenient to deal with the It

Judges reasoning in the context of the particular points on appeal. [17] Before us, the argument narrowed to whether causes of action number one

(breach of contract); three (implied term of agreement); and four (breach of fiduciary duty) should be struck out. The terms of the debenture

[18]

To follow the arguments it is necessary at this point to intrude the terms of

the ANZ debenture. The relevant provisions were conveniently and accurately set out by the High Court Judge at [10] [12] of the judgment under appeal. We now set out that portion of the judgment in full:

[10] The security for the debenture is provided by cl 1.1 which reads: Security: The Company charges and assigns in favour of the Bank all its right, title and interest (present and future, legal and equitable) in, to, under or derived from the Secured

Property, as continuing Security for the payment of the Secured Indebtedness and for the performance of all other obligations that the Company has agreed to perform under this Debenture, each Facility Document or any Collateral Security. Secured Property is defined as meaning: all the assets of the Company whatsoever and wheresoever, both present and future and whether held in trust or beneficially owned by the Company, including without limitation those assets that are acquired by the Company after the crystalisation of the floating charge created under this Debenture; Assets are defined as including: the whole or any part of the relevant persons business, undertaking, property, revenues and choses in action (in each case, present and future, legal and equitable): [11] The debenture created a fixed charge over all choses in action and for their absolute assignment by way of mortgage. Clause 1.2 relevantly provides: Fixed Charge: The security interest created by the Company in clause 1.1 is a fixed charge over each of the following kinds of property (present and future, legal and equitable): (j) all choses in action including, without limitation, all book debts and other monetary debts;

Clause 1.3 provides: Assignment of Choses in Action: The security interest created by the Company in clause 1.1 is an absolute assignment by way of mortgage of all the Companys book debts, other monetary debts and other choses in action (present or future). If requested by the Bank, the Company will promptly give written notice of this assignment to such person or classes of persons as the Bank may specify, being persons from whom the Company is entitled to receive or claim any chose in action, book debt or other monetary debt. [12] Clause 3 of the schedule to the debenture specifies that the choses in action assigned under cl 1.3 include rights arising under the agreements with Telecom. It provides: Assignment: The security interest created by the Company in clause 1.3 of the Debenture includes an absolute assignment by way of mortgage of:

(a)

all the Companys right, title, interest, powers and remedies (present and future, legal and equitable) in and to each Agreement (but in each case specifically excluding any of the obligations or responsibilities (whether of a monetary nature or otherwise) of the Company therein); the Earnings,

(b)

to secure payment to the Bank of the Secured Indebtedness and performance and compliance by the Company of all other obligations which the Company has agreed to perform under the Debenture. The agreements referred to in cl 3(a) are defined as including the agreements between Telecom and Sintel which were essential to Sintels business operations and earnings are defined as including monies payable to Sintel arising out of or in connection with the agreements.

Was there an assignment of the choses in action?

[19]

It is convenient to note here a point which was put in issue by Sintels then

counsel, the late Mr J R Fardell QC, in the High Court but which has now fallen away. [20] It will be observed that the charging clause in the ANZ debenture is a very

broad one. It extends to choses in action, present and future, legal and equitable. Nevertheless, Mr Fardell argued that the causes of action against Telecom are not choses in action for the purposes of the debenture. Relying on Re New Bullas Trading Limited [1994] 1 BCLC 485 (CA) he suggested that a distinction should be drawn between choses in action which arise in the ordinary course of business and those which do not. Rodney Hansen J rejected that argument. He said at [15]: If it is a chose in action, it is part of the secured property and that is the end of the matter. We note that in Commissioner of Inland Revenue v Agnew [2002] 1 NZLR 30 the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council declined to follow New Bullas. We agree with the Judge that the choses in this case were plainly part of the secured property, and that ANZ had a genuine commercial interest in taking the assignment.

The effect of the assignment

[21]

The next question is therefore: what are the legal consequences of the

assignments? [22] Mr Kos QC suggested that the straightforward application of property law

principles should govern the outcome [of this application]. His proposition is that Sintel has alienated causes of action one, three and four. [23] Mr Kos said that a statutory assignment of causes of action one and four has

occurred; those rights of action vested in ANZ in 1997, and have never been reassigned to Sintel. Accordingly, Mr Kos submitted, Sintel cannot maintain the present action in respect of those causes of action. [24] Mr Kos accepted that in relation to cause of action three, that particular

assignment could only be an equitable assignment, as occurred in 1997. Legal title is with Sintel as bare trustee only; the consent of Telecom/ANZ is required before commencement of suit, and those parties would also require to be joined in respect of that cause of action. None of these events have occurred. [25] Mr Billington QC argued that if the settlement agreement is set aside, the

way is clear for it to proceed against Telecom for all sums due to it by Telecom. He said that even if the assignment was not set aside, the causes of action against Telecom are not stayed or able to be struck out for the reasons contended by Telecom. [26] In particular, Mr Billington argued that: The bringing of the claims against Telecom do not amount to a dealing with the secured property in terms of the debenture (cl 7.1(a)), requiring the consent of the debenture holder; or Even if consent was required, Telecom could not withhold its consent as to do so would be in breach of the debenture holders obligation to act in

good faith, and an obligation not to put a clog on the equity of redemption. [27] We do not find it necessary to discuss the assignment points at any length.

We agree with Mr Kos that, on the facts, there have been assignments of the character suggested by him, and for the reasons which we have set out in [23] and [24] above. [28] We have also expressed our agreement with the view of the High Court Judge

that the choses in action were plainly within the terms of the debenture. A limited exception?

[29]

The real issue in the case is whether there is a limited exception which

enables Sintel to sue in respect of the requisite causes of action in this case, notwithstanding the particular assignments. [30] Mr Kos argued that this is a strict property rights issue which has arisen in a

commercial context: Sintel has put itself beyond an ability to sue. [31] Mr Billington argued that it would be wrong to produce a result which is

commercially nonsensical; permits Telecom to take advantage of its own wrongdoing (ie, by using the assignment which was procured by Telecoms misrepresentations), which equity will not allow; and overrides the effectiveness of remedies open to Sintel on its causes of action to set aside the settlement agreement and assignment. [32] The resultant issue may perhaps best be framed as a question: Is there an

obligation in equity on the debenture holder to act in good faith vis--vis the debtor in relation to its dealing with or holding of the secured property, including an affirmative duty to sue, or at least not resist a suit, as may be appropriate? [33] It is necessary to introduce here some further factual background to better

indicate exactly what it is that Sintel is complaining about. Mr Billington said:

10.

The material aspects for present purposes are that Telecom through a process of misrepresentation (including but not limited to transit fees and destination fees due, quantum of payments made and received by Korea Telecom, the amount of third party carrier deductions): 10.1 10.2 Prevented the reversal of the liquidation of Sintel; Misled the liquidators, receivers and ANZ as to the basis and quantum of Sintels possible claims against Telecom and Sintels and Telecoms entitlements under contracts with Telecom by substantially understating and/or misstating the same; Which in turn caused the liquidators, receivers and ANZ to enter into the Settlement Agreement and the Assignment on terms far less favourable than they otherwise would have if they had each known the true position; Resulting in Telecom thereby procuring, by misrepresentation, for its own benefit the assigned Debenture upon which it now relies exclusively for its arguments to strike out Sintels claims.

10.3

10.4

11.

In other words, by an extended process of wrongdoing, Telecom obtained the means by which it now alleges it can prevent the action being brought by a wronged party (Sintel) by relying on the benefit of its own wrong (ie the Assignment and the Debenture).

[34]

Mr Billington relied on the fundamental principle that equity will not

allow a party to take advantage of its own wrongdoing . [I]t is inequitable for Telecom to be permitted to rely on the Assignment in order to prevent Sintel from pursuing causes of action against Telecom in [the] event that the Settlement Agreement is set aside . [35] He further said:

95. The bringing of a strike out application, if successful, would be to give effect to an improper purpose on the part of Telecom; namely, to use a technical argument obtained by the fruits of misrepresentation and deceit in order to control and defeat a proceeding against it and prevent it from being heard on the merits at trial. A narrow procedural point should not defeat and preclude an overarching claim for misrepresentation, especially where the procedural argument only arises as a result of deceit and misrepresentation complained of.

96.

97.

The legal standing for Telecom to bring a strike out application in respect of Sintels causes of action only arises due to wrongful conduct of Telecom inducing the Settlement Agreement and the Assignment. If these had not occurred, Telecom would not be in a position to bring the application to strike out and would have to face the case on its merits.

[36]

The narrow technical argument referred to by Mr Billington goes, in large

part, to the question which has been much debated over the years of who must be a party to the proceedings involving an assignment. [37] In the High Court Rodney Hansen J held that, [t]here is no reason in

principle why an assignor may not sue to recover a chose providing the assignee is a party to the action, or I would add, is fully protected by other means (at [41]). [38] The High Court Judge relied upon Three Rivers District Council v Bank of

England [1995] 4 All ER 312 (CA). There Staughton LJ said at 322:

In my judgment the assignor still has a cause of action at law; and the assignee has a cause of action in equity. That was ultimately the position of Sir Patrick Neill in his reply, and I think that it is right. It is the solution which comes nearest to reconciling all the authorities. It allows the assignee still to use the assignors name, if he wishes, as before the 1873 Act. Of course the assignees claim prevails, if he insists upon it. The 1981 Act says so. But where the assignee is a party to the action, and expressly declines to make a claim, I can see no reason why the assignor would not claim what is his legal right.

[39]

And Peter Gibson LJ said at 325:

every civil court has to administer law and equity on the basis that whenever there is any conflict between common law and equity, the rules of equity shall prevail, every court is to continue to give effect to equitable rights and subject thereto to common law rights and the courts jurisdiction is to be exercised so as to secure that, as far as possible, all matters in dispute are completely and finally determined and the multiplicity of proceedings is avoided.

[40]

Mr Kos emphasised as we have accepted that the ANZ debenture effected

an absolute assignment by way of security (that is, mortgage) of all Sintels preexisting and future assets. Those assets were assigned first to ANZ in 1997, then to Telecom in June 2000 when the ANZ debenture was assigned.

[41]

It was then argued that, by bringing claims against Telecom, Sintel is acting

in breach of the express terms of the ANZ debenture. This is because the ANZ debenture prevents any dealing with assets without prior written consent of the debenture holder, and no such consent has even been sought by Sintel. [42] Then it is said, even if consent had been sought, there would be sound

reasons for withholding it. Mr Kos argued that Telecom could properly withhold consent in order to protect ANZs interest, because ANZ presently has a 28% interest in the debenture (which Telecom holds in trust for ANZ); and, ANZ has a potential reversionary interest if the June 2000 settlement is unwound. [43] On the specific issue of any equitable obligations Mr Kos said that any

obligation to allow Sintel to realise or deal with the secured property would functionally force upon mortgagees an obligation to use it or lose it. That is, the (mortgage) debenture holder would have to exercise their rights (at peril of claims arising from the manner in which they do so) or effectively surrender them to allow the debtor to deal with the secured property. This, Mr Kos submitted, would be contrary to the view taken by the Privy Council in China & South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan [1989] 3 All ER 839, and this Court in Apple Fields Ltd v Damesh Holdings Ltd [2001] 2 NZLR 586 at 599. Discussion

[44]

It seems to us that the fundamental principle contended for by Mr Billington

must be correct: equity will not allow a party to take advantage of its own wrongdoing (if such it proves to be). There must be an ability in a case such as this to enable a party in the position of Sintel to bring proceedings, if necessary in its own name, to set aside the underlying agreement, notwithstanding that formal effect has been given to the transaction. [45] Such an exception to the operation of the usual rules (which are undoubtedly

as Mr Kos stated them to be) can strike deep into commercial transactions, and it ought itself to operate on the considerations which underpin the application of equitable doctrines.

[46]

One such constraint is that a party seeking to resort to equity will normally

look first to resort to his or her legal remedies, for equity supplements the law. Here, if it were to redeem the debenture, Sintel could sue as of right on the bases it is presently putting forward. But the realistic position is that it is in liquidation, there are no funds available to it, and the liquidators have, for whatever reason, shown no interest in the proceeding. Further, Mr Billington also noted that, in the

circumstances of this case, if the appellant was successful on this application, but the settlement agreement was eventually set aside, the respondent would encounter subsequent limitation issues. [47] A second broad concern is that a party seeking to resort to equity should act

timeously. This litigation has been regrettably prolonged. There was a gap of almost four years between the June 2000 settlement and the issuing of these proceedings in April 2004. Nevertheless, the proceedings were not out of time. [48] A third kind of concern is the potential impact on third parties of the

litigation. Prejudice to innocent third parties has long been regarded as a matter of real significance in equity. The short point here is: would ANZ against whom no complaint has been made, on the merits be put at risk by this litigation? The answer to that appears to be that ANZ would even if Sintel is successful need to be restored to the status quo ante. In short, it would be no worse off. [49] We add for completeness that the fact that the agreement in question is a

settlement agreement does not mean it is necessarily protected by the law of privilege (see Cooper v Van Heeren [2007] NZCA 207 at [27] [42]). This is also an implicit recognition that the law may have to examine whether the underlying agreement was made or is otherwise lawful. Conclusion [50] [51] The appeal is dismissed. Sintel will have costs of $6,000 and usual disbursements.

Solicitors: Russell McVeagh, Wellington for Appellant Duncan Cotterill, Auckland for Respondent

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Aplg 2014Documento25 pagineAplg 2014api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- New ZealandDocumento7 pagineNew Zealandapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Asia Pacific Live Gaming 20140513Documento34 pagineAsia Pacific Live Gaming 20140513api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- 8win Cost Proposal Om 220514 1Documento11 pagine8win Cost Proposal Om 220514 1api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Skill Game Agreement Jan 3 2014Documento15 pagineSkill Game Agreement Jan 3 2014api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Macau Skill Game Timeline 2014Documento2 pagineMacau Skill Game Timeline 2014api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- QJ Spot The Ball Lo Summary Version Mdme 14 04 14Documento6 pagineQJ Spot The Ball Lo Summary Version Mdme 14 04 14api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- High Court Judgement - Hansen 2006-06-04Documento16 pagineHigh Court Judgement - Hansen 2006-06-04api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Scan 0002Documento16 pagineScan 0002api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Scan 0003Documento17 pagineScan 0003api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Scan 0001Documento1 paginaScan 0001api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Audiofax 1995Documento1 paginaThe Audiofax 1995api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Hallo 056 AdsDocumento10 pagineHallo 056 Adsapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Scan 0004Documento20 pagineScan 0004api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Claims Mount Up Against Telecom Stuff CoDocumento1 paginaClaims Mount Up Against Telecom Stuff Coapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Sintel 1asoc As Filed 151 06 07Documento47 pagineSintel 1asoc As Filed 151 06 07api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Telecom Dragged Into Leaky Home Scrap Stuff CoDocumento2 pagineTelecom Dragged Into Leaky Home Scrap Stuff Coapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Phone Dating Company Sintel Struck Off Stuff CoDocumento1 paginaPhone Dating Company Sintel Struck Off Stuff Coapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Telecom Fights 40m Tax Bill Stuff CoDocumento1 paginaTelecom Fights 40m Tax Bill Stuff Coapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Timeline 20131009Documento1 paginaTimeline 20131009api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Remote Slots HLD v1Documento34 pagineRemote Slots HLD v1api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Preliminary Proposal For Skilled Game Platform Macau 20131009Documento5 paginePreliminary Proposal For Skilled Game Platform Macau 20131009api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Remote Slots Milestone1Documento2 pagineRemote Slots Milestone1api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Remote Slots Project brdv1Documento19 pagineRemote Slots Project brdv1api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Entertainment Gaming Asia June 2012 PresentationDocumento32 pagineEntertainment Gaming Asia June 2012 Presentationapi-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Company Remote Slots Development Workorder v0Documento7 pagineThe Company Remote Slots Development Workorder v0api-53711077Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nakednewsasia 2012Documento67 pagineNakednewsasia 2012api-53711077100% (1)

- Heraldic Code of The PhilippinesDocumento59 pagineHeraldic Code of The PhilippinesJohana MiraflorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- PLEB Online Filing ProcedureDocumento4 paginePLEB Online Filing ProcedurechikayNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re Burger Boys, Inc., Debtor. South Street Seaport Limited Partnership, Creditor-Appellant v. Burger Boys, Inc., Doing Business as Burger Boys of Brooklyn, Debtor-Appellee, 94 F.3d 755, 2d Cir. (1996)Documento11 pagineIn Re Burger Boys, Inc., Debtor. South Street Seaport Limited Partnership, Creditor-Appellant v. Burger Boys, Inc., Doing Business as Burger Boys of Brooklyn, Debtor-Appellee, 94 F.3d 755, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2010-03-24 General Orders of The US District Court, Central District of California SDocumento269 pagine2010-03-24 General Orders of The US District Court, Central District of California SHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Nessuna valutazione finora

- AVAILABILITY OF THE SERVICE: Monday To Friday 8:00 A.M. To 6: P.M. 1. Application For Authority To Travel AbroadDocumento6 pagineAVAILABILITY OF THE SERVICE: Monday To Friday 8:00 A.M. To 6: P.M. 1. Application For Authority To Travel AbroadMark Anthony Sta RitaNessuna valutazione finora

- 16 DEC 2019 EZS1438 08:35 6E 09:05 Ez3Dfsv S619: (BEG) Belgrade (GVA) GenevaDocumento1 pagina16 DEC 2019 EZS1438 08:35 6E 09:05 Ez3Dfsv S619: (BEG) Belgrade (GVA) GenevaRahul PeddiNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocumento15 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Today's Fallen Heroes Wednesday 6 November 1918 (1523)Documento31 pagineToday's Fallen Heroes Wednesday 6 November 1918 (1523)MickTierneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sps. Marasigan v. Chevron PhilsDocumento2 pagineSps. Marasigan v. Chevron PhilsMond RamosNessuna valutazione finora

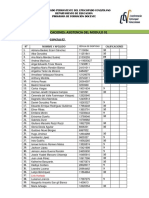

- Calificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry GonzalezDocumento2 pagineCalificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry Gonzalezadriana ecarriNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of The FRIA LawDocumento13 pagineSummary of The FRIA LawKulit_Ako1100% (3)

- Strategic Options For Iran: Balancing Pressure With DiplomacyDocumento45 pagineStrategic Options For Iran: Balancing Pressure With DiplomacyThe Iran Project100% (3)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- H2 CMC Practice (AJC 2018 JC1 MYCT)Documento5 pagineH2 CMC Practice (AJC 2018 JC1 MYCT)PotatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Salazar vs. Philippines - GuiltyDocumento6 pagineSalazar vs. Philippines - Guiltyalwayskeepthefaith8Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jenine Tameka Jones, A206 501 154 (BIA Sept. 21, 2015)Documento6 pagineJenine Tameka Jones, A206 501 154 (BIA Sept. 21, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNessuna valutazione finora

- 20210322165537521825Documento85 pagine20210322165537521825Ayasha RinkeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Holocaust Web QuestDocumento4 pagineHolocaust Web QuestalaskarldonaldNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 10 Shutter IslandDocumento3 pagineCase 10 Shutter IslandAnkith ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 JurisprudenceDocumento19 pagine1 JurisprudenceCindy Bacsal TrajeraNessuna valutazione finora

- MB vs. Reynado DigestDocumento2 pagineMB vs. Reynado DigestJewel Ivy Balabag DumapiasNessuna valutazione finora

- Annexure - A Application For Registration of Shipping Lines / Steamer Agents / Airlines / Consol Agents / Any Other PersonDocumento2 pagineAnnexure - A Application For Registration of Shipping Lines / Steamer Agents / Airlines / Consol Agents / Any Other PersonrajaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Exactly Is An Unusual Sexual Fantasy - PDFDocumento13 pagineWhat Exactly Is An Unusual Sexual Fantasy - PDFJohn C. YoungNessuna valutazione finora

- Maurice Bucaille's InspiringDocumento2 pagineMaurice Bucaille's Inspiringsonu24meNessuna valutazione finora

- 85-Year-Old Tewksbury Woman Accuses Town, Police of Civil Rights ViolationsDocumento37 pagine85-Year-Old Tewksbury Woman Accuses Town, Police of Civil Rights ViolationsEric LevensonNessuna valutazione finora

- Gavrilo PrincipDocumento1 paginaGavrilo PrincipDaniraNessuna valutazione finora

- Zulm Hindi MovieDocumento21 pagineZulm Hindi MovieJagadish PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Mattis IndictmentDocumento8 pagineMattis IndictmentEthan BrownNessuna valutazione finora

- 219 Order On Motion For Summary JudgementDocumento21 pagine219 Order On Motion For Summary JudgementThereseApelNessuna valutazione finora

- Murray McleodDocumento3 pagineMurray Mcleodgrumpyutility4632Nessuna valutazione finora

- Land Sale Agreement Between Chief Kayode and Miss GegelesoDocumento3 pagineLand Sale Agreement Between Chief Kayode and Miss GegelesoDolapo AmobonyeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sales & Marketing Agreements and ContractsDa EverandSales & Marketing Agreements and ContractsNessuna valutazione finora

- Profitable Photography in Digital Age: Strategies for SuccessDa EverandProfitable Photography in Digital Age: Strategies for SuccessNessuna valutazione finora

- Law of Contract Made Simple for LaymenDa EverandLaw of Contract Made Simple for LaymenValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (9)