Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

History of Inclusive Education - Final Draft - Veleno

Caricato da

api-163017967Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

History of Inclusive Education - Final Draft - Veleno

Caricato da

api-163017967Copyright:

Formati disponibili

History of Inclusive Education 1 Running Head: THE EVOLUTION OF INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

The Evolution of Inclusive Education in America: A Historical Review Pasquale Veleno University of Calgary

History of Inclusive Education 2

The concept of inclusive education originated with a values-based, civil rights premise that students with disabilities should not be segregated from their non-disabled peers for the purposes of their education (Stainback & Stainback, 1990). While this belief influenced the development and progression of the inclusion movement in education, it was not until the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975 that special education truly began experiencing significant gains in this area (Sailor, 2002). The introduction of this legislation served to guarantee free public education to all children with disabilities, and was most beneficial to those individuals with the most severe disabilities, who had otherwise previously been denied appropriate educational services. Since the introduction of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, educational policies within the United States have undergone an evolutionary process that has gradually moved from the goal of mainstreaming students with disabilities toward integration, and finally to inclusion. The greatest distinction between these respective policies essentially amounted to the degree to which participation within regular education classrooms was mandated. While mainstreaming tended to focus on the amount of time and specific circumstances under which students with mild to moderate disabilities would successfully spend in a general education classroom (Filler, 1996; Sailor, Kleinhammer-Tramill, Skrtic, & Oas, 1996), integration policies sought to educate students with severe disabilities within proximity to their general education peers, and provided increased opportunities for interaction between them (Sailor, 2002). This essentially meant that students with severe disabilities were generally placed in

History of Inclusive Education 3 contained classrooms within neighbourhood public schools, with limited integrated experiences during lunch, recess, and special occasions (Sailor, 1991). By the early 1990s, educational policies began focusing on placing students with varying levels of disabilities within general education classrooms, while providing appropriate services and supports to facilitate overall success (Filler, 1996). This was referred to as the inclusion movement, and it differed from integration insofar as it placed greater emphasis on full participation and opportunities for interaction between students of all levels of education (Sailor, 2002). Inclusion was defined by Sailor (1991) and Turnbull, Turnbull, Shank, and Leal (1995) in the following manner: 1. All students receive education in their neighbourhood school or school they would otherwise attend, regardless of disability. 2. A natural proportion of students with disabilities occur at each school site. 3. A zero-reject philosophy exists insofar as students will not be excluded on the basis, type or extent of disability. 4. No self-contained special education classes will exist; while school and general education placements are age- and grade- appropriate. 5. Emphasis is placed on cooperative learning and peer instruction. 6. Special education supports are in place within the general education classroom and other integrated environments. Inclusion placed a great emphasis on child-centred educational practices, whereby teachers were required to assess children academically, socially, and culturally to best

History of Inclusive Education 4 individualize and optimize learning (Thompkins & Deloney, 1995). While these educational practices were viewed as progressive and worthwhile, many scholars and educators came to interpret this movement toward educational reform in a critical manner, and resisted it, often clashing with one another in the process. Furthermore, concern surfaced regarding the financial cost and poor academic and social outcomes for students in the special education system (Conner, 2008). This created a polarization within the American educational system that continues to exist to some extent today.

Inclusion and Related Legislation The roots of inclusive education can be traced back to the decision of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which legally guaranteed each individual living within the United States equal protection of the laws (Conner, 2008). This decision was particularly poignant for children with disabilities, who prior to this, were refused enrolment or were provided inadequate educational services by their local schools. By the mid 1970s, the federal courts and U.S Congress moved to enact special education rights for children with disabilities (Santrock, 2008), which culminated in the passing of Public Law 94-112, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975). This act mandated that all students with disabilities be given free and appropriate education (FAPE), and introduced the concept of Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). This essentially stipulated that, to the maximum extent possible, students with disabilities had to be individually evaluated and placed in an appropriate educational setting. This setting could range from a variety of options, including the home, partial/full placement

History of Inclusive Education 5 in separate schools, or hospital settings, etc., based on the severity of the childs disability and social and academic needs (Conner, 2008). Specifically, the act required that students with disabilities be educated to the maximum extent possible with their non-disabled peers. This was referred to as mainstreaming. Moreover, this law introduced funding for the purposes of facilitating the education of children with disabilities. The act also required that school districts provide a mandatory dispute resolution process so that parents of disabled children could challenge decisions made about their childrens education. Subsequent to the exhaustion of these procedures, parents were then authorized to seek judicial review of the administrations decision. The LREmandate tended to alter the structure by which special education was delivered by making the resource model the primary option (Kavale & Forness, 2000). This typcially manifested in the emergence of the resource room and special education teachers, who provided academic instruction for specified periods of time to students whose primary placement was the general education classroom. This allowed the student to spend significant portions of the day within the general education setting, and in so doing, the student was considered to meet criteria for mainstreaming. While the introduction of LRE was intended to help ensure optimal placement decisions for students with disabiltiies, criticisms existed regarding its interpretation. Disability rights activitsts tended to view this mechanism as a legal loophole which allowed for the non-integration of students with disabiltiies into schools, and considered placement options to be overly restrictive (Reynolds, 1977), while to others, LRE provided necessary protection, flexibility and individualization of placement for students who struggled to remain within the general classroom setting (Conner, 2008). Many

History of Inclusive Education 6 remained unconvinced that the provision of special education services would appreciably benefit individuals with disabilties, and raised opposition to the operation of a dual system (Stainback & Stainback, 1984), which was deemed to be ineffecient, expensive, and politically incorrect. Furthermore, while mainsteaming policies tended to focus on accessibility, questions remained regarding instructional methodologies, professional practice, and more inclusive placements (Kavale & Forness, 2000). By the mid 1980s, increased enrollments of minority students in special education, coupled with an overreliance on measurement tools used to determine disability, and the continued segregation of students with disabilities in poorly-run special education programs heightened the need for educational reform (Conners, 2008). In response to this, Madeline Will, Assistant Secretary to the U.S. Department of Education in charge of special education and rehabilitation programs, introduced the Regular Education Initiative (REI) in 1986. The primary objective of this special education initiative was to mainstream students with mild to moderate disabilities by placing them in regular classroom settings. This involved merging general and special eduation to create a more uniform system of education (Gartner & Lipsky, 1987; Will, 1986), however, the REI was poorly received insofar as critics perceived it to be nonspecific, flawed (Kaufman, 1989) and counterproductive for the purposes of helping students with disabilties (Conner, 2008). This heralded the gradual initiation of statewide legislation focused on the placement and support of students with disabilities in general education classrooms (Lipsky & Gartner, 1997). In 1990, the state of Vermont passed legislation that emphasized placing and supporting students with disabilities in general education settings and required principals to be responsible to all students,

History of Inclusive Education 7 regardless of status or ability (Lipsky & Gartner, 1997). Other states, such as Kentucky, Colorado, and Pennsylvania soon made changes to legislation that reflected a serious commitment to the integration movement. Reynolds (1989) referred to this movement as progressive inclusion (p.7). In 1990, Public Law 94-142 was reauthorized as the Individuals with Disabilties Education Act (IDEA) (Santrock, 2008). This legislation served to increase public awareness of student disabilities, and went further than any preceding legislation to increase accessibility for all members of society. Furthermore, IDEA served to populalrize the concept of full inclusion (Conner, 2008). Full inclusion was characterized by attendance of students with disabilities in their home-based schools, a zero-reject policy, age-appropriate placements, no self-contained classes, and special education support provided in integrated learning environments (Sailor, 1991). Although IDEA was ammended in 1997 and then reauthorized in 2004 as the Individuals wth Disabilities Educational Improvement Act, this legislation outlined broad mandates for all children with disabilties (Hallahan & Kauffman, 2006; Hardman, Drew, & Egan, 2006; Smith, 2007), including evaluation and eligibility determination, appropriate education and an individualized education plan (IEP), and education in the least restrictive environment (LRE) (Santrock, 2008). While IDEA placed empahsis on increased access to the general education curriculum, this legislation mandated that schools provide appropriate education services to children who required them, based upon appropriate assessment and evaluation practices involving the participation and collaboration of parents. IDEA also served to include and expand the role and influence

History of Inclusive Education 8 of general educators, by granting teachers the opportunity to participate as members of the IEP team. Unfortunately, the introduction of IDEA also served to further deepen the divide between those who were ideologically in favour of inclusion, and those who preferred the special education model. Many cases went to trial. Sailor (2002) outlined the details of a particularly signficant case, Holland vs. Sacremento USD, where a local school district spent over a million dollars to prevent a single little girl, Rachel Holland, who had moderate disabilities, from being included in a general education classroom. This district lost, and, in fact, the tenor of virtually all of the significant court cases on the topic have seemed to impel the principle of inclusive education (p.8).

Attitudes and Beliefs Attitudes and beliefs about the usefulness of inclusive education vary and continue to generate debate today. Larivee and Cook (1979) identified a number of longstanding factors which contribute to the reluctance of critics to accept inclusive education as progressive educational reform: academic concerns associated with the possible negative effects of integration on general academic progress; socioemotional concerns related to the negative aspects of segration; and, instructional concerns, related to the support, training, and experiential issues aspects associated with teaching students with disabilties. Scruggs and Mastropieri (1996) conducted a quantitative research synthesis of 28 studies that looked at the perceptions of general education teachers regarding the

History of Inclusive Education 9 inclusion of students with disabilities. While a strong majority of the teachers surveyed indicated support for the concept of inclusion, a significantly lower percentage of teachers surveyed expressed willingness to include students with disabilities in their own classrooms. Furthermore, less than one third of the respondents indicated that they believed the general education classroom was the ideal educational placement setting for these students. This was primarily attributed to teacher perceptions regarding the severity of student disability and the perception of increased levels of teacher competence and responsibility required to support these individuals (Kavale & Forness, 2000). The lack of resources and appropriate teacher training available to be able to provide specialized care became a common theme within general education. The overall reluctance on the part of general education teachers to participate in inclusive practices therefore, was interpreted to be related to perceived practical barriers rather than philosophical barriers. Moreover, suspicions arose regarding administration motives for supporting the inclusion movement. Since there were potential cost savings associated with reduced need for special education, some believed that the push for inclusive education had far more to do with budgetary motives rather than ideological motives (Thompkin & Deloney, 1995). Though the concept of inclusion was generally supported by parents of children with disabiltiies, some parents and advocates for those with disabilties also expressed concerns regarding the inclusion movement. Lieberman (1992) indicated that parents of children with disabilities fought for individualized, specialized attention that was typically associated with special education classroom environments. The push toward inclusive education was perceived by some as culminating in a reduction in available

History of Inclusive Education 10 resources, specialized programming and expertise. Furthermore, some parents worried about the possiblity of maltreatment by non-disabled peers (Thompkin & Deloney, 1995). Proponents of inclusive educaton argue that as a result of changes to educational policies and the introduction of relevant legislation, there are a much greater number of children with disabilties who receive competent, specialized services than in the past (Santrock, 2008). For many children, inclusion in the regular classroom with appropriate modifications and specialized services is appropriate (Friend, 2006), however this must be tempered with the realization that the focus on inclusion has sometimes led to unnecessary, inappropriate accomodations within the classroom that do not always benefit children with disabilities. As such, advocates promote an individualized approach that does not always involve full inclusion, but allows for special education outside of the classroom, if necessary. While agreeing that the need for specially trained professionals to help children with disabilities achieve their potential is necessary, in addition to the introduction of program/curriculum adaptations to meet individual requirements, critics also point to the need for teachers to recognize that all students, including children with disabilities in particular, must be challenged to meet their academic potential, and should therefore also be held accountable for their efforts, or lack thereof, toward that end (Kauffman et al., 2004). According to Kavale and Forness (2000), empirical evidence is necessary to strengthen the research program so that it is progressive. By 1980, this was manifested in the LRE concepts, however problems with research findings persisted, including the fact that students in special education classes were not progressing as

History of Inclusive Education 11 was initially expected. Advocates of full inclusion, however, have not been able to adequately present empirical evidence of its effectiveness. Rather, arguments for the adoption of inclusive education were largely based on moral, ideological and philosophical grounds (Kavale & Forness, 2000). The goal of achieving freedom and equality of opportunity, while idealistic, is powerful nevertheless, and therefore difficult to challenge. Furthermore, from a legal perspective, the American courts have clearly indicated that where integration is feasible, segregation is illegal, regardless of the school districts philosophical perspective on integration (Ringer & Kerr, 1988, as cited in Thompkins & Deloney, 1995). Generally speaking, both proponents and opponents of inclusive education agree on a select number of points: with appropriate staff development and support, more students with mild disabilities can be successful within regular education classrooms; and, better research, improved coordination of services between special and regular education, and administrative support are important for serving students with disabilities (Hubert, 1994, as cited in Thompkins & Deloney, 1995). Moreover, supporters of inclusive education cite the fact that special education efficacy studies demonstrate no significant advantages for special education placements (Reynolds, 1989), thus lending further ammunition for the practice of inclusion.

Current Findings and Future Directions Meta-analyses and comparitive studies that have compared the educational outcomes of students with developmental disabilties in inclusive classrooms have found

History of Inclusive Education 12 no difference in educational outcomes or positive effects for inclusion (Alper & Ryndak, 1992; Hunt & Goetz, 1997). Saint-Laurent, Fournier, and Lessard (1993) found no significant differences in academic outcomes for students with moderate developmental disabilities in inclusive, community based, or traditional segregated classrooms. The authors concluded that integration had a positive influence on social and behavioural outcomes, while providing academic, functional, and basic skills instruction that was equal to that provided in more segregated settings. This is consistent with results reported in Lipsky and Gartner (1995), whereby the authors noted negligible differences in academic achievement for students with mild disabilities in integrated settings compared to those in resource programs. Moreover, they noted more favorable attitudes toward the integrated model, while acknowledging reduced operating costs with integrated/inclusive settings. According to Lewis (1994), students with disabilities in inclusive environments "improve in social interaction, language development, appropriate behaviour, and selfesteem" (p. 72). Proponents of inclusion also suggest that as regular and special education faculty work cooperatively together in integrated settings, their coordinated work tends to raise their own expectations for their students with disabilities, as well as student self-esteem and sense of belonging. Hocutt (1996) identified a number of other important outcomes pertaining to inclusion research: 1. Childrens academic and social success is more greatly affected by the quality of instruction provided rather than placement characteristics. Inclusion is most

History of Inclusive Education 13 effective when teachers have received appropriate training, planning time, and appropriate support staff. 2. Children with a longstanding history of severe emotional disturbances are best served by participation in vocational education at the secondary school level, in conjunction with integration via other school activities, such as sports, etc. 3. Children with hearing impairments achieve some academic gains, but suffer lower self-esteem when placed in integrated classroom settings. 4. Children with mild intellectual delays and adaptive behaviour problems appear to benefit from having a supportive teacher, competent instruction, and supportive classmates moreso than non-disabled children. 5. Non-disabled children are not negatively affected by the inclusion of children with disabilities into the classroom as long as support services are provided (Cole, Waldron, & Majid, 2004). Studies examinng the impact of inclusion on non-disabled students found no evidence of harmful effects, while noting that attitudes, values and beliefs were positively affected (York, Vandercook, MacDonald, Heise-Neff & Caughey, 1992; Haring, Breen, Pitts-Conway, Gaylord-Ross, & Gaylord-Ross, 1987; Biklen, Corrigan, & Quick, 1989; Murray-Seegert, 1989). Nisbet (1994) also confirmed that no negative outcomes were reported for normally developing children when exposed to preschool integration practices. More importantly, Staub and Perck (1994) identified several positive benefits of inclusion for nondisabled students, including: reduced fear of human differences, resulting in increased comfort and awareness; growth in social

History of Inclusive Education 14 cognition; improvements in self-concept; development of personal principles; and, warm and caring friendships (p.37).

Conclusions There has been an increasingly strong push toward inclusive education over the last several decades. Legislative changes in the United States, originating with the introduction of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975) and culminating with the Individuals wth Disabilities Educational Improvement Act (2004) have helped spur the progression and evolution of educational policies away from segregation, toward mainstreaming, integration, and inclusion, respectively. While critics of this ideological approach remain, advocates of the inclusion movement have helped transition the inclusion movement through three distinct phases: (a) the civil rights argument; (b) enforcement litigation; and (c) federal, research-driven policy implementation (Sailor, 2002). The focus of inclusion has now appeared to shift from acceptance of educational policy, to the effective delivery and implentation of educational policy in this regard. Inclusive education appears here to stay. Admittedly, the thrust toward educational reforms have created tension between educators, scholars and child advocates based upon ideological values, perceptions regarding motives, and associated stresses related to the limited resources and increased burden placed upon the educational system, in general. Proponents of this movement have presented moral and ideological arguments for the continued implementation of inclusive practices, though available research has pointed to the many behavioural,

History of Inclusive Education 15 academic and social benefits associated with inclusive education for students with disabilities. Evidence also supports the notion that non-disabled peers may benefit from inclusive practices. Further research, however, is required in all areas pertaining to inclusive education to develop a greater understanding of associated benefits and potential drawbacks.

History of Inclusive Education 16 References Alper, S., & Ryndak, D.L. (1992). Educating students with severe handicaps in regular classes. The Elementary School Journal, 92, 373-387. Biklen, D., Corrigan, C., & Quick, D. (1989). Beyond obligation: Students relations with each other in integrated classes. In D.K. Lipsky & A. Gartner (Eds.), Beyond separate education: Quality education for all. (p. 207-221). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. Cole, M. (2005). Culture and cognitive development in phylogenetic, historical, and ontogenetic perspective. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.). New York: Wiley. Conner, D.J. (2008). Supporting inclusive classrooms: A resource. New York City Task Force for Quality Inclusive Schooling. New York. Filler, J. (1996). A comment on inclusion: Research and social policy. Social Policy Report, X (2/3), 3132. Friend, M. (2006). Special education (IDEA 2004, Update ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Gartner, A., & Lipsky, D.K. (1987). Beyond special education: Toward a quality system for all students. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 367-390. Hallahan, D.P., & Kauffman, J.M. (2006). Exceptional learners (10th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Hardman, M.L., Drew, C.J., & Egan, M.W. (2006). Human exceptionality (8th ed., Update). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

History of Inclusive Education 17 Haring, T.G., Breen, C., Pitts-Conway, V., Gaylord-Ross, M.L., & Gaylord-Ross, R. (1987). Adolescent peer tutoring and special friend experiences. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 12 (4), 280-286. Hunt, P., & Goetz, L. (1997). Research on inclusive educational programs, practices, and outcomes for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 31, 3-29. Larrivee, B., & Cook, L. (1979). Mainstreaming: A study of the variables affecting teacher attitude. The Journal of Special Education, 13, 315-324. Lieberman, L.M. (1992). Preserving special educationfor those who need it. In W. Stainback, & Stainback (Eds.), Controversial issues confronting special education: Divergent perspectives. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Lipsky, D.K., & Gartner, A. (1995). The evaluation of inclusive education programs. NSERI Bulletin, 2 (2), 2-9. Lipsky, D.K., & Gartner, A. (1997). Inclusion and school reform: Transforming Americas classrooms. Baltimore: Paul Brookes. Kauffman, J.M. (1989). The regular education initiative as a Reagan-Bush education policy: A trickle-down theory of education of the hard to teach. The Journal of Special Education, 23 (3), 256-278. Austin, TX: ProEd. Kavale, K.A. & Forness, S.R. (2000). History, rhetoric and reality: Analysis of the inclusion debate. Remedial and Special Education, 21 (5), 279-296.

History of Inclusive Education 18 Reynolds, M.C. (1989). An historical perspective: The delivery of special education to mildly disabled and at-risk students. Remedial and Special Education, 10 (6), 711. Reynolds, M.C., & Birch, J.W. (1977). Teaching exceptional children in all Americas schools. Reston, VA: The Council for Exceptional Children. Sailor, W. (1991). Special education in the restructured school. Remedial and Special Education. 12 (6), 8-22. Sailor, W. (2002). Devolution, school/community/family partnerships, and inclusive education. Whole-School Success and Inclusive Education. Columbia University. Sailor, W., Kleinhammer-Tramill, J., Skrtic, T., & Oas, B. K. (1996). Family participation in New Community Schools. In G. H. S. Singer, L. E. Powers, & A. L. Olson (Eds.), Redefining family support: Innovations in publicprivate partnerships (pp. 313332). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. Santrock, J.W. (2008). Educational Psychology (3rd ed.) McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Stainback, W., & Stainback, S. (1984). A rationale for the merger of special and regular education. Exceptional Children, 51 (2), 102-111. Stainback, W., & Stainback, S. (Eds.). (1990). Support networks for inclusive schooling. Interdependent integrated education. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Smith, B. (2007). Introduction to special education (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

History of Inclusive Education 19 Thompkins, R., & Deloney, P. (1995). Inclusion: The pros and cons. SEDL Bulletin, 4 (3). Retrieved August 9, 2009, from http://www.sedl.org/change/issues/issues43.html. Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Shank, M., & Leal, D. (1995). Exceptional lives: Special education in todays schools. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill. Will, M.C. (1986). Educating children with learning problems: A shared responsibility. Exceptional Children, 52, 411-416. York, J., Vandercook, T., MacDonald, C., Heise-Neff, C., & Caughney, E. (1992). Feedback about integrating middle-school students with severe disabilities in general education classes. Exceptional Children, 58 (3), 244-258.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Jkahn - BMP - RevisedforschoolportfolioDocumento9 pagineJkahn - BMP - Revisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- CR - Success StoryDocumento13 pagineCR - Success Storyapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Kitz - Transition Plan - 2ndrevisedforschoolportfolioDocumento12 pagineKitz - Transition Plan - 2ndrevisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Pats Resume - Portfolio - 2012Documento6 paginePats Resume - Portfolio - 2012api-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

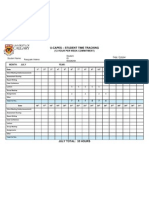

- U-Capes - Student Time Tracking: (12 Hour Per Week Commitment)Documento6 pagineU-Capes - Student Time Tracking: (12 Hour Per Week Commitment)api-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Jkahn - Bar - RevisedforschoolportfolioDocumento6 pagineJkahn - Bar - Revisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- KP Psyed RPT Jan 31st 2011 - RevisedforportfolioDocumento17 pagineKP Psyed RPT Jan 31st 2011 - Revisedforportfolioapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Parental Discipline and The Use of Aversive Procedures - VelenoDocumento23 pagineParental Discipline and The Use of Aversive Procedures - Velenoapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Ed Interventions For Children With Tbi - VelenoDocumento22 pagineEd Interventions For Children With Tbi - Velenoapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment Plan - Case Study 1 - Veleno - Apsy693 71Documento7 pagineAssessment Plan - Case Study 1 - Veleno - Apsy693 71api-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Ethics 5 - Vulnerable PopulationsDocumento21 pagineEthics 5 - Vulnerable Populationsapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Intervention Plan Final - Janssen Southworth Veleno - ModifiedDocumento30 pagineIntervention Plan Final - Janssen Southworth Veleno - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- PatvelenocertificateDocumento1 paginaPatvelenocertificateapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- 633-Revised1 - My Counselling TheoryassignmentDocumento26 pagine633-Revised1 - My Counselling Theoryassignmentapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Ethics Assignment 2 - Final Version - Janssen and VelenoDocumento11 pagineEthics Assignment 2 - Final Version - Janssen and Velenoapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Copy - Review of Fasd Paper - ModifiedDocumento9 pagineFinal Copy - Review of Fasd Paper - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Resources Assignment - VelenoDocumento26 pagineResources Assignment - Velenoapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vineland-Ii Presentation - Monique and Pat - Final VersionDocumento22 pagineVineland-Ii Presentation - Monique and Pat - Final Versionapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Exam Answers - Veleno - ModifiedDocumento10 pagineExam Answers - Veleno - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Homogeneity of Variance TutorialDocumento14 pagineHomogeneity of Variance Tutorialapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Smith-Veleno - Native Tendencies Paper - Rev - ModifiedDocumento15 pagineSmith-Veleno - Native Tendencies Paper - Rev - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Janssen Veleno Assignment 3Documento12 pagineJanssen Veleno Assignment 3api-87386425Nessuna valutazione finora

- Veleno - Letter of Intent - Final Draft 2Documento12 pagineVeleno - Letter of Intent - Final Draft 2api-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ctopp Presentation - Second Version - ModifiedDocumento22 pagineCtopp Presentation - Second Version - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exam - Reports - Draft - Veleno - Storm - Final VersionDocumento13 pagineExam - Reports - Draft - Veleno - Storm - Final Versionapi-163017967100% (1)

- Vineland-Ii Review - VelenoDocumento14 pagineVineland-Ii Review - Velenoapi-163017967100% (1)

- Veleno - Autism Intervention and Best Practices - RevmodDocumento19 pagineVeleno - Autism Intervention and Best Practices - Revmodapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - ModifiedDocumento22 pagineImpact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - Modifiedapi-163017967Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Think and Grow RichDocumento22 pagineThink and Grow RichChandra Ravi100% (1)

- Peer Assesment 1 Sheet - RagDocumento3 paginePeer Assesment 1 Sheet - Ragapi-569743488Nessuna valutazione finora

- Proposal ApipDocumento42 pagineProposal ApipDiana Khoirunning TiasNessuna valutazione finora

- (Ulrich, D. Younger, J. Brockbank, W. & Ulrich, M., 2011) The State of The HR ProfessionDocumento18 pagine(Ulrich, D. Younger, J. Brockbank, W. & Ulrich, M., 2011) The State of The HR ProfessionJoana CarvalhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter, Rationale and QuestionnaireDocumento3 pagineLetter, Rationale and QuestionnaireLordannie John LanzoNessuna valutazione finora

- Preparation and Evaluation of Catharanthus Roseus Face Sheet Mask SerumDocumento4 paginePreparation and Evaluation of Catharanthus Roseus Face Sheet Mask SerumInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Anterior Knee PainDocumento11 pagineAnterior Knee PainViswanathNessuna valutazione finora

- Bambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisDocumento1 paginaBambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisShai ReenNessuna valutazione finora

- Posse ProcessDocumento4 paginePosse Processapi-597185067Nessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3 DELTA One To OneDocumento16 pagineModule 3 DELTA One To OnePhairouse Abdul Salam100% (3)

- MAK-AND-MUBS ScholarshipDocumento69 pagineMAK-AND-MUBS ScholarshipTimothy KawumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Term Paper Recommendation SampleDocumento4 pagineTerm Paper Recommendation Sampleafdtfhtut100% (1)

- Mycom Nims ProptimaDocumento4 pagineMycom Nims ProptimasamnemriNessuna valutazione finora

- General Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestDocumento84 pagineGeneral Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestUmber Ismail82% (11)

- TABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL - 2ndDocumento10 pagineTABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL - 2ndKaren CobachaNessuna valutazione finora

- GRD 7 Endterm 1 Exam: All SubjectsDocumento113 pagineGRD 7 Endterm 1 Exam: All SubjectsBryan MasikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Surf Flyer Report 1Documento3 pagineSurf Flyer Report 1TJ McKinney100% (2)

- 1649Documento336 pagine1649tariq khanNessuna valutazione finora

- Thinking Dialectically About Intercultural RelationshipsDocumento3 pagineThinking Dialectically About Intercultural RelationshipsHarits RamadhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Web Application Development-Assignment Brief 1Documento5 pagineWeb Application Development-Assignment Brief 1Khoa NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Read Aloud ListDocumento3 pagineRead Aloud Listapi-238747283Nessuna valutazione finora

- Multi-Criteria Decision MakingDocumento52 pagineMulti-Criteria Decision MakingD'Mhan Mbozo100% (1)

- Diego Gallo Macin Janet Santagada Eac 150 NBQ 09. Mar. 2018 Research Skills AssignmentDocumento5 pagineDiego Gallo Macin Janet Santagada Eac 150 NBQ 09. Mar. 2018 Research Skills AssignmentDiego Gallo MacínNessuna valutazione finora

- Shifting From Engineer To Product ManagerDocumento2 pagineShifting From Engineer To Product ManagerRegin IqbalNessuna valutazione finora

- 2009-10-07 015349 Five StepDocumento1 pagina2009-10-07 015349 Five StepAndrew PiwonskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Harvard ReferencingDocumento30 pagineHarvard ReferencingPrajna DeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Carl Jung's and Isabel Briggs Myers'Documento5 pagineCarl Jung's and Isabel Briggs Myers'Venkat VaranasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Final English Hiragana BookletDocumento18 pagineFinal English Hiragana BookletRoberto MoragaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018020799Documento3 pagine2018020799chintanpNessuna valutazione finora

- Thai BookDocumento4 pagineThai BookVijay MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching English: How to Teach English as a Second LanguageDa EverandTeaching English: How to Teach English as a Second LanguageNessuna valutazione finora

- World Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12Da EverandWorld Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12Nessuna valutazione finora